- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

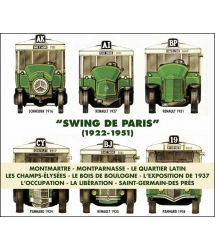

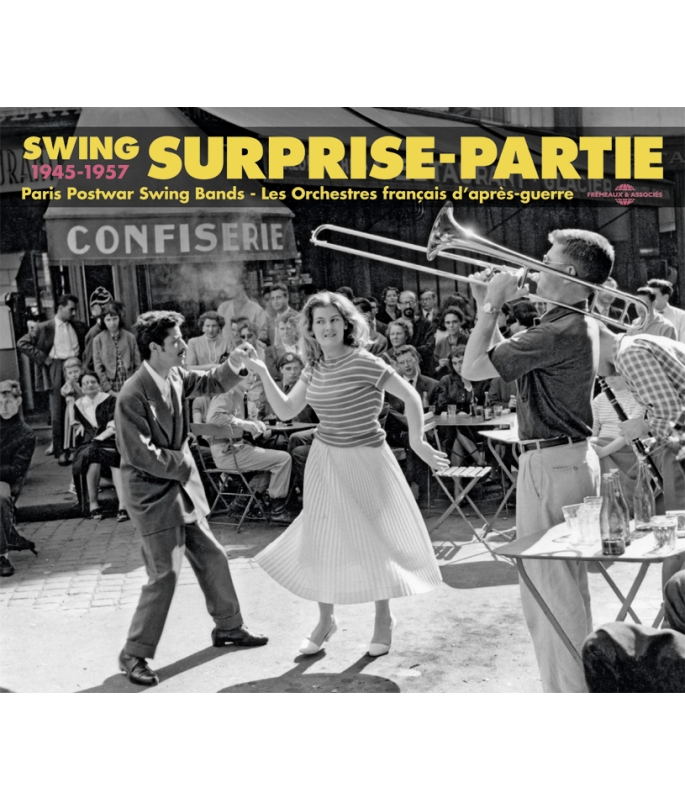

LES ORCHESTRES FRANÇAIS D’APRÈS-GUERRE - PARIS POSTWAR SWING BANDS

Ref.: FA5299

EAN : 3561302529929

Artistic Direction : PIERRE CARLU

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 10 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

LES ORCHESTRES FRANÇAIS D’APRÈS-GUERRE - PARIS POSTWAR SWING BANDS

LES ORCHESTRES FRANÇAIS D’APRÈS-GUERRE - PARIS POSTWAR SWING BANDS

When modern jazz arrived after the war, the swing bands allowed young people to continue dancing to the sounds of jazz before they’d ever heard of Rock & Roll! Thanks to Pierre Carlu's choice of hits from the best of these bands, listeners can now enjoy the furious experience of those Swing “surprise-parties” for themselves. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Rockin' The BluesChristian Bellest et son orchestre00:03:041945

-

2Delhi Swing en SolMichel Ramos et son orchestre00:02:531945

-

3Torpedo JunctionPierre-Séverin Luino et son orchestre00:03:061945

-

4Asking For SwingCharley Bazin et ses Fumière Boys00:02:531945

-

5Is You Is Or Is You Ain'tJean Faustin et son orchestre00:03:101945

-

6That's The Moon My SonRay Ventura et son orchestre00:02:571946

-

7November BluesHubert Rostaing et son orchestre00:03:231946

-

8UndecidedRay Ventura et son orchestre00:02:291946

-

9In The MoodRay Ventura et son orchestre00:03:191946

-

10On The Sunny Side Of The StreetHubert Rostaing et son orchestre00:03:201946

-

11BuffaloHubert Rostaing et son orchestre00:03:041946

-

12ClaridgeCamille Sauvage et son orchestre jazz00:02:441946

-

13Shoo Fly PieTony Proteau et son orchestre00:02:581946

-

14I Should CareAndré Ekyan et son orchestre00:02:141946

-

15The Sergeant Was ShyGeorgie Kay et son orchestre du Jazz Club français00:03:101946

-

16Black SwingNoël Ghiboust et son grand orchestre de jazz00:03:231946

-

17Cement MixerMaurice Moufflard et son orchestre00:02:441947

-

18Hamps Boogie WoogieMaurice Moufflard et son orchestre00:02:351947

-

19Leave Us LeapFernand Clare et son orchestre00:03:051947

-

20Mop MopAndré Ekyan et son orchestre00:02:561947

-

21PerdidoAndré Ekyan et son orchestre00:03:021947

-

22On Basie StreetAimé Barelli et son orchestre00:02:541947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Jungle TownSébastien Solari et son orchestre00:02:491947

-

2Martini GinCamille Sauvage et son orchestre jazz00:02:301948

-

3Toolie Oolie DoolieRené Leroux et son orchestre du Lido00:02:471948

-

4Les Feuilles mortesAimé Barelli et son orchestre00:03:051949

-

5Week End dans les oubliettesCamille Sauvage et son orchestre jazz00:02:491949

-

6AlwaysJacques Hélian et son orchestre00:03:591949

-

7Blues 50Aimé Barelli et son orchestre00:02:231949

-

8RécréationNoël Ghiboust et son grand orchestre de jazz00:02:481951

-

9Tout çaNoël Ghiboust et son grand orchestre de jazz00:03:151951

-

10Un p'tit coup de chapeauJerry Mengo et son orchestre00:02:471951

-

11BravoPhilippe Brun et son orchestre00:02:351951

-

12Thème 52Aimé Barelli et son orchestre00:02:481951

-

13C'est bon de rêverAlix Combelle et son orchestre00:03:291953

-

14LuciferNoël Ghiboust et son grand orchestre de jazz00:03:041953

-

15Missie RopeinAlix Combelle et son orchestre00:02:491953

-

16Captain Cook's TourAlix Combelle et son orchestre00:03:351953

-

17NuagesHubert Rostaing et son orchestre00:03:031953

-

18Jerry's BoogieJerry Mengo et son orchestre00:02:541954

-

19Moonlight SerenadeAlix Combelle et son orchestre00:02:511954

-

20Opus 1Jerry Mengo et son orchestre00:02:421954

-

21En écoutant mon coeur chanterJerry Mengo et son orchestre00:02:231954

-

22Avec ces yeux-làEddie Barclay et son orchestre00:03:131957

SWING SURPRISE-PARTIE

SWING SURPRISE-PARTIE1945-1957

Les Orchestres français d’après-guerre

Paris Postwar Swing Bands

La fin des orchestres de jazz swing en France

Nous sommes en Mai 1945, c’est l’armistice en France, plus de cinq années terribles viennent de prendre fin et la vie va recommencer comme avant.Comme avant, vraiment ?Non, l’histoire ne se répète jamais, ce qui s’est passé avant guerre ne reviendra pas et il est évident qu’on n’a pas envie de recommencer comme en 40. Mais bien sûr, rien ne change brusquement. La période de l’occupation a vu se développer en France un jazz de style résolument “swing”. Ce style était apparu un peu avant guerre, et l’isolement dans lequel la France va se trouver pendant cinq ans va encourager le jazz de type swing à prospérer. C’est normal, au moins à Paris, ça permet de se changer les idées. Il ne faut pas oublier que le style swing, initié aux Etats-Unis avant la guerre, était basé sur du jazz de grand orchestre adapté à la clientèle des casinos et des palaces, donc festif, surtout pour un pauvre peuple sous la botte !A la fin des hostilités le jazz, donc le swing, sont triomphants. Noël Chiboust célèbre sur la marque de disque swing l’arrivée des Américains avec un retentissant Welcome1. Les Aimé Barelli, Alix Combelle, Django Reinhardt, Hubert Rostaing et tous les autres sont au top. Mais comme on dit, tout a une fin. Que se passe-t-il donc ? Eh bien, les disques américains sont de retour, très progressivement c’est vrai. Mais que font-ils entendre ? Une musique qui n’a plus rien à voir (ou plutôt à entendre !) avec le swing de la fin des années 30.

Eh oui, la musique de jazz a évolué aux Etats-Unis pendant que la France était occupée, et celle-ci a découvert un monde musical nouveau grâce aux tout premiers disques reçus en France par Charles Delaunay, qui avait été très actif pendant toute l’occupation en éditant sur sa marque de disques swing (bien nommée!) tous les orchestres de swing justement. Ces nouveaux disques faisaient découvrir deux musiciens que la France de 1945 ignorait, mais qui allaient définitivement changer le monde du jazz : il s’agissait du trompettiste Dizzy Gillespie et du saxophoniste alto Charlie Parker. Excellente occasion pour de jeunes musiciens doués de se lancer dans une nouvelle épopée jazzistique : les Michel De Villers, Jean-Claude Fohrenbach, Bernard Peiffer, Hubert et Raymond Fol, Henri Renaud et bien d’autres, sans oublier André Hodeir, vont s’éclater, d’autant que les musiciens américains de la nouvelle école se mettent à venir en France pour se mêler à eux.Et comme si ça ne suffisait pas, voilà que dans une cave du Quartier Latin, un orchestre se met à recréer la musique de King Oliver ! L’orchestre de Claude Luter au “Lorientais” aura un succès énorme, amplifié par la venue, un peu plus tard, de Sidney Bechet qui va s’installer à Paris et jouer avec ces jeunes et leurs suiveurs. Dans ces atmosphères nouvelles, radicalement différentes de celles des orchestres swing de l’occupation, que vont devenir ceux-ci, définitivement oubliés des amateurs de jazz, tout au moins des amateurs purs ?

Il n’était pas question de baisser les bras. En effet, la musique swing avait engendré une génération importante de très bons musiciens, excellents lecteurs et souvent bons solistes, surtout les grandes pointures. Tous ces musiciens et leurs orchestres ne demandent qu’à jouer, ils animaient déjà les dancings et cabarets pour faire danser le swing aux nombreux amateurs ravis de se défouler avec une excellente musique. Il suffit de continuer en profitant de l’arrivée en France des nouvelles danses typiques, en premier lieu le boléro (en fait une variation de la rumba), la samba (mais il s’agissait plus de guaracha) et, last but not least, le mambo, que les orchestres swing savaient jouer mieux que quiconque, car cette danse demandait d’assez grandes formations et la musique ressemblait au swing. Que demander de plus ? Certains ont qualifié ces orchestres de commerciaux, ce qui pouvait se justifier par le fait qu’ils n’apparaissaient pas en concert, ils faisaient danser. Mais même les meilleurs grands orchestres jazz, tels Chick Webb ou Erskine Hawkins faisaient danser sans donner de concerts, et ils étaient donc commerciaux, d’ailleurs qui ne l’était pas ?Dans la deuxième moitié des années 40 et pendant les années 50, les orchestres swing vont donc, non seulement subsister, mais pour les meilleurs, progresser en prenant exemple sur les grands orchestres swing américains de l’après-guerre, style Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey et Woody Herman. Certains orchestres swing vont même se créer après-guerre, citons par exemple l’orchestre de Tony Proteau ou encore l’orchestre de Camille Sauvage, un peu à cheval entre orchestre de danse et orchestre de jazz mais qui, et c’est le principal, savait swinguer !

Des orchestres de danse purs, qui n’existaient pas pendant la guerre, font leur apparition et peuvent jouer du swing de façon convaincante, par exemple Sébastien Solari ou Jean Faustin. Mais évidemment, ce sont les “ténors” de l’époque swing qui vont être les plus convaincants lorsqu’ils font danser ce qu’on appelait le “fox-swing” pour montrer que cette danse venait du fox-trot, en plus dynamique, et pour faire la distinction avec les “slow-fox”, qui apportaient un peu de repos. Inutile de préciser que les morceaux choisis ont privilégié les swing purs et durs, mais quelques slow ont été quand même placés ça et là, pour montrer les qualités de ces orchestres sur tempo lent. Ils n’enregistraient plus sur Swing et dûrent évidemment changer de marque de disques et se diriger vers les collections de danse. C’est ainsi que les marques Pathé, Odéon, Polydor, Selmer, Cantoria ou Ducretet-Thomson les accueillirent, et c’est là le drame, car ces disques de danse étaient joués en Surprise-Partie sans aucun soin, et n’étaient pas conservés quand les disques étaient trop usés ou que l’on ne voulait plus danser dessus. De plus, ils disparaissaient vite fait des bacs des disquaires pour être remplacés par des disques de danse nouveaux. Un exemple particulièrement éloquent est celui de l’arrivée, au cours des années 50, du rock & roll qui prit littéralement le pouvoir sur les pistes de danse ou dans les soirées privées. C’est d’ailleurs l’époque où les grands orchestres swing disparaissent presque complètement de leur lieux habituels, avec quelques exceptions quand même, Aimé Barelli au “Sporting Club” de Monte-Carlo, Pierre Delvincourt au “Lido” de Paris. L’auteur de ces lignes se souvient même d’un orchestre de 15 musiciens jouant tout à fait swing sur la plage de Saint-Jean de Luz devant le casino en Juillet 1958, eh oui, mais ce n’était que les feux du couchant !Restons plutôt entre 1945 et 1957 et profitons de l’ambiance encore très swing de l’après-guerre. Que ce soit dans les brasseries des grandes villes, dans les casinos et dancings des stations de vacances, on entendait autant de swings que de tangos ! Les grands orchestres existant déjà sous l’Occupation

En 1945, cinq ou six orchestres tenaient le haut du pavé, ils avaient enregistré abondamment sur la marque swing pendant la guerre, et ils étaient prêts à continuer, mais sans l’étiquette “jazz”. Aimé Barelli : Ce musicien, monté à Paris en 1940, avait commencé chez Raymond Legrand, puis Fred Adison, orchestres de variétés de qualité, qui comprenaient nombre de musiciens de jazz. Il joua dans les orchestres formés à partir de celui d’Adison pour les besoins des enregistrements, comme Raymond Wraskoff ou le “Jazz Victor”, et entra ainsi dans le prestigieux “Jazz de Paris”, sous la direction d’Alix Combelle. Son premier orchestre s’appelait d’ailleurs “Aimé Barelli et son orchestre du Jazz de Paris”, mais il trouva ensuite un type de formation qui lui convenait parfaitement : lui à la trompette, quatre saxophonistes et une section rythmique complète, ce qui donnait un son de big band avec seulement 9 musiciens. Ce n’est que vers 1946-1947 qu’il engagea une seconde trompette et un cinquième saxe, en l’occurrence un baryton, qui augmentèrent le son de la formation. Une section de cordes fut également ajoutée, au moins pour certaines interprétations. Puis l’orchestre s’étoffa de plus en plus avec des sections de cuivres encore plus importantes.Après la guerre, Barelli fut engagé dans un club aux Champs-Elysées, “Sa Majesté”, mais il passa rapidement à quelques centaines de mètres de là, aux “Ambassadeurs”, devenu depuis “Espace Cardin”. A cette époque, il y avait encore beaucoup de morceaux de jazz dans le répertoire, dont certains venaient de l’époque swing. D’ailleurs, l’orchestre Barelli assura le début et la fin de la “Semaine du Jazz” organisée par Frank Bauer et Simone Volterra au théâtre Marigny en Mai 1948. Il parut aussi dans un film au tout début des années 50 “Les Joyeux Pèlerins”, qui avait au moins le mérite de faire entendre un excellent morceau de jazz, qui figure dans ce coffret.

Il donna aussi un concert à l’Alhambra en 1953 qui comprenait plusieurs morceaux de jazz. Pendant un moment, à la même époque, l’orchestre anima les séances de “Jazz Variétés” au “Rex”. C’est l’époque où les pianistes Francy Boland et Martial Solal et le batteur Roger Paraboschi, tous trois jeunes musiciens en train de “faire” le nouveau jazz, font partie de l’orchestre. Et il y avait eu un moment étonnant, c’est celui du concert de Dizzy Gillespie à Pleyel le 30 Mars 1952 : à la fin, l’orchestre Aimé Barelli arrive sur scène, Barelli va se fondre dans sa section de trompettes et laisse le leadership à Dizzy qui interprètera deux morceaux de son répertoire du big band de quelques années plus tôt... hénaurme ! Mais au cours des années suivantes, il y eut par force de plus en plus de morceaux de variété et de danse non jazz, avec néanmoins de temps en temps des swings très jazzy, au moins jusqu’au départ de l’orchestre pour Monte-Carlo, au prestigieux “Sporting-Club”. Il faut dire que si l’orchestre sonnait toujours bien, c’était grâce à un arrangeur hors pair, le saxophoniste baryton Armand Migiani, qui fit aussi des enregistrements sous son nom, soit de jazz soit de variétés. L’orchestre d’Aimé Barelli tint bien le coup, toujours au “Sporting Club”, jusqu’en 1986. Aimé Barelli plia son ombrelle en 1995. Alix Combelle : A part Django Reinhardt, devenu une star internationale dans les années 40, Alix Combelle est sans doute le plus grand musicien de jazz de l’époque swing. Il commença sa carrière au début des années 30, son premier enregistrement comme soliste a lieu en 1935 avec le Quintette du Hot-Club de France qui, lui aussi, en était encore à ses débuts. Il participe en 1937 à la première session pour la toute nouvelle marque de disques swing en compagnie de Coleman Hawkins et Benny Carter aux côtés de son collègue André Ekyan, un quatuor de saxes qui laissera un grand souvenir dans le jazz en France. Il dirige pour les besoins de l’enregistrement son premier orchestre en 1938, les “Hot-Club Swing Stars”, joue chez Fred Adison et enregistre avec le “Jazz Victor”, avec le tout nouvel orchestre de Noël Chiboust, avec l’ensemble d’Aimé Barelli et Hubert Rostaing et bien entendu avec son propre orchestre. A cette époque il était partout, quelque chose comme le roi de l’époque swing en France.

L’ultime consécration arriva quand il devint le patron du célèbre “Jazz de Paris”. Il continua à diriger diverses formations dans les années 40, enregistrant pour Swing, puis Columbia, Vogue (avec Buck Clayton ainsi que Jonah Jones), Philips et enfin pour le Club français du disque. Il joue alors régulièrement au “Club des Cinq”. En Octobre 1953, il apparait dans l’orchestre de Lionel Hampton pour un mémorable concert au théâtre de Paris. Comme tous les autres, il sera obligé, dans les années 50, d’enregistrer de la variété et des danses typiques, mais il restera fidèle au jazz jusqu’à la fin. Ses derniers engagements parisiens furent “Chez Mimi Pinson”. En 1958, il eut l’occasion de jouer avec Buck Clayton le vieux copain, mais aussi Vic Dickenson, Stuff Smith et Kenny Clarke, et une trace de cette rencontre existe sur disque. Après quoi, en 1963, il se retira dans l’ouest, à Follainville, où il ouvrit le “Club de la Tour” mais s’arrêta de jouer quelque temps après pour raisons de santé et ne fit plus beaucoup parler de lui jusqu’à sa disparition en 1978.Noël Chiboust : C’était un perfectionniste, qui avait commencé très tôt, chez les “Collégiens” de Ray Ventura, l’orchestre français le plus connu à la fin des années 20 et au début des années 30. Il jouait alors du violon. On le retrouve quelques années plus tard à la trompette, il joue chez Michel Warlop, le grand violoniste de jazz, de nouveau chez Ray Ventura, chez Raymond Legrand, il accompagne Jean Tranchant, bref il ne chôme pas. Il faut attendre 1938 pour le trouver au saxophone et à la clarinette, qu’il n’abandonnera plus. Il se trouve au début de la guerre chez Fred Adison où il montre de réelles qualités d’arrangeur. Son premier orchestre enregistré comprend le pianiste de Fred Adison, Raymond Wraskoff, et il ne cesse de remanier son orchestre pour mieux répondre à ses dons d’arrangeur.

A la libération, il continue de jouer du jazz, mais il quitte la marque Swing pour Selmer car il va commencer à faire comme tout le monde, introduire des thèmes de variété. Il joue alors au “Schubert” et son arrivée chez Ducretet-Thomson le voit s’éloigner de plus en plus du jazz. Il continuera à diriger son orchestre de nombreuses années et se retirera dans le midi, en arrêtant alors la musique.Hubert Rostaing : C’est un cas, car c’est le seul musicien de jazz swing qui continuera de faire des disques de jazz sur la marque Swing après la guerre, mais en sextette la plupart du temps. Il avait commencé à peu près en même temps qu’Aimé Barelli, avec qui il développera une excellente collaboration. Ses débuts à Paris furent “Chez Mimi Pinson” en 1940, où Alix Combelle le découvrit alors qu’il jouait de la clarinette et du bandonéon ! Son style de clarinette doit certainement allégeance à Benny Goodman, mais il se mit rapidement au saxo-ténor et surtout au saxo-alto qu’il jouait dans un style coulant, un peu comme Woody Herman. Il enregistrera avec les musiciens rescapés de l’orchestre Don Redman en 1946, il apparaîtra en 1947 dans l’orchestre de Jacques Hélian pour interpréter le “concerto de clarinette” d’Artie Shaw, pas moins ! Il enregistrera avec Rex Stewart et ses musiciens lors de leur venue en France en décembre 1947. Il est alors en résidence au “Carroll’s”. Ce n’est que dans les années 50 qu’il sera obligé de jouer autre chose que du jazz. Il tiendra un sextette de danse néanmoins très jazz puisqu’il comprenait le tromboniste américain Nat Peck et le batteur “Mac-Kac” Reilles. Son grand orchestre ne jouait pratiquement plus de jazz, mais on trouvera une belle exception dans ce coffret !

André Ekyan : C’est un vieux de la vieille que l’on voit déjà chez Grégor au début des années 30. Son style d’alto est nettement inspiré de Benny Carter, excusez du peu ! D’ailleurs, il était avec lui pour cette séance swing avec Coleman Hawkins. Il a toujours préféré les petites formations – on se souvient de ses prestations avec Django Reinhardt2. Il ne dirigera un grand orchestre swing qu’à partir de 1947 et, à part les premiers enregistrements, le répertoire sera hors du jazz, qu’il s’agisse de variété ou de musique typique.Jerry Mengo : L’amateur de jazz a surtout entendu parler de lui lorsqu’il est revenu de captivité en 1941, et qu’il prit en charge le nouveau “Jazz de Paris”, que venait de quitter Alix Combelle. Mais il avait commencé sa carrière musicale bien avant, dans des orchestres pas très jazz et pas très connus (tel les orchestres de Rapha Brogiotti et de Serge Glykson). Après le “Jazz de Paris”, où Christian Bellest a remplacé Aimé Barelli comme premier trompette, Jerry Mengo se concentre un moment sur les petites formations. Il en avait déjà dirigés chez Swing pendant l’occupation. Il passe chez ABC Jazz Club, une petite marque fondée pendant la guerre avec Yvonne Blanc. A la fin de la guerre, on le trouve entre autres à “La Villa d’Este” puis “Chez Carroll’s” et au “Beaulieu”. Ce n’est qu’au tournant des années 40 à 50 que Mengo renoue avec le big band, et quel big band ! D’abord chez Ducretet-Thomson, puis chez RCA, notre batteur nous offre non seulement des morceaux originaux, mais aussi des “tubes” américains qui swinguent. On n’entendra plus beaucoup parler de lui ensuite, sauf qu’en 1973, il dirigera encore un orchestre pour accompagner le grand trompettiste américain Bill Coleman !

Les orchestres de jazz plus tardifs

Christian Bellest : Pendant toute l’occupation, ce musicien fut très sollicité par les meilleurs orchestres swing. Comme Barelli, Christian Bellest passa chez Fred Adison, avant de rentrer dans le “Jazz de Paris”, où il n’était évidemment que le second trompette. Mais il deviendra 1er trompette dans le deuxième “Jazz de Paris” sous la direction de Jerry Mengo. Il jouera aussi chez Raymond Legrand. Son style, immanquablement inspiré de celui de Barelli, est malgré tout aisément reconnaissable, une grande qualité à une époque où la plupart des trompettistes sonnaient un peu pareils. En 1945, Christian Bellest assemble un orchestre avec un certain nombre de “pointures” pour une session sur la marque Blue Star. Sur les quatre morceaux enregistrès, deux sont du jazz tout ce qu’il y a de plus convaincant. Il jouera un temps dans l’orchestre du “Lido”, dirigé par René Leroux après le départ de Tony Proteau, il fut aussi chez Jacques Hélian et son orchestre en 1956. Il quittera progressivement le monde du jazz-swing dans les années 50, et son propre orchestre sera utilisé essentiellement pour la variété.Philippe Brun : Il jouait déjà chez Gregor, à la manière de Bix Beiderbecke et avait fait l’admiration du critique de jazz Hugues Panassié. On le retrouve quelques mois plus tard chez les Collégiens de Ray Ventura à leurs débuts, ayant échangé le style de Bix contre celui de Louis Armstrong. C’est ensuite un long séjour dans l’orchestre anglais de Jack Hylton que Panassié, par contre, n’aimait pas du tout. A la fin des années 30, il est de retour chez Ray Ventura et enregistre sous son nom avec un important contingent de cet orchestre3 où un certain Jacques Hélian tient le saxophone ténor.

On le trouvera en Suisse pendant la plus grande partie des années d’occupation de la France. Ce n’est qu’après la guerre qu’il rejoue dans notre pays. Il apparaît dans les concerts “Jazz Variétés” du Rex, mais il joue alors dans des orchestres de danse ne faisant qu’occasionnellement du swing, en particulier l’orchestre de M. Philippe-Gérard. Il enregistre avec ces musiciens ainsi que sous son nom quelques faces intéressantes avec vraisemblablement Armand Molinetti à la batterie. Il s’éloignera progressivement du métier pour raisons de santé, et la dernière fois qu’on le verra sera en 1986 à la fête organisée à la Bibliothèque Nationale de la rue Vivienne en l’honneur de Charles Delaunay qui venait de faire don de sa considérable discothèque à cette vénérable institution.Maurice Moufflard : Il était trompettiste de pupitre, en particulier chez Jo Bouillon, mais après la guerre, il fonda un orchestre swing de qualité mais sans grande personnalité et enregistra sur Selmer, une marque dévolue à la danse. Pourtant, en 1949, il aura l’occasion absolument unique d’accompagner Charlie Parker (oui, vous avez bien lu, un des plus grands musiciens de jazz !) sur un morceau au cours d’une émission de radio. Il continuera de jouer pour la danse au cours des années 50, mais en petite formation.Pierre-Sèverin Luino : Les amateurs de jazz séniors se souviennent de ce musicien comme troisième trompette dans le “Jazz de Paris”, Aimé Barelli et Christian Bellest étant les deux premiers. Ce qui signifiait qu’il était dans l’orchestre de Fred Adison à cette époque. Ce que l’on sait moins, c’est qu’il dirigea son orchestre de danse à la “Coupole” pendant 26 ans, de 1948 à 1974 ! Belle performance, exceptionnelle dans ce milieu. Il n’a que peu enregistré sous son nom.Fernand Clare (Ferdinand Carracilly)4 : “L’orchestre qui jouait comme des Américains” (Jack Diéval, 1946). Sans commentaire, surtout quand on sait que l’orchestre de Glenn Miller venait de quitter la France ! Il est vrai que Fernand Clare était un musicien non seulement doué mais travailleur et, si son orchestre n’était pas spécialement original, il était très professionnel, ce qui lui permettra d’être très demandé par les casinos français de l’après-guerre.

En fait, il commença très tôt à jouer du violon, de l’accordéon et de la batterie, ce qu’il complètera plus tard par le saxophone et la clarinette. Sa carrière se fera surtout sur la côte d’Azur, où il commence à 16 ans. En 1935, il démarre au grand casino de Juan-les-Pins, sous la direction du pianiste américain Herman Chittison. C’est ensuite le Palm-Beach de Cannes. Lorsque vient l’occupation, il part en Suisse et joue avec Philippe Brun. Retour en France en 1945, il fonde alors son orchestre, joue à l’hôtel “Ruhl” de Nice, au “Sporting-Club” de Monte-Carlo, à Deauville, puis vient à Paris, joue à l’Olympia, fait un tabac à la Nuit du Jazz en 1947, enregistre pour Pacific, Odéon, Cantoria, avant de retourner finir sa carrière à Nice, au Palais de la Méditerranée.Tony Proteau : C’est en 1943 que la section de saxes d’un jeune saxophoniste alto, Tony Proteau, fusionne avec l’ensemble de Claude Dubuc. On retrouve à la Libération tout ce petit monde, affecté un moment à la 7ème armée américaine, puis dans l’Armée de l’Air française. C’est le “Collège Rythme”, le saxophoniste René Leroux le dirige au tout début, puis laisse de nouveau le leadership à Tony Proteau, qui va faire de cet ensemble un très beau grand orchestre qui sera engagé le 20 Juin 1946 rien moins qu’au “Lido” sur les Champs-Elysées. C’est un big band déjà très moderne que l’on va entendre dans ses faces Blue Star. En 1948, il reconfie la direction de son orchestre à René Leroux qui le conduira jusqu’en 1953, date à laquelle Pierre Delvincourt, le bassiste, en prendra la direction. Pendant ce temps, Tony Proteau, désireux de jouer exclusivement du jazz, aura fondé un autre orchestre, qui participera au Festival de Jazz de Pleyel, organisé en 1949 par Charles Delaunay, où il se fit copieusement siffler5 par les “intégristes” du jazz qui ne pouvaient pas supporter un orchestre que n’aurait pas renié Woody Herman ! Il animera aussi des séances de “Jazz Variétés” où il accompagnera Sidney Bechet et Django Reinhardt entre autres.

Il n’échappera pas ensuite à l’obligation d’enregistrer de la variété, comme tout le monde ! On peut regretter que ce musicien disparut rapidement de la scène musicale française car il savait diriger un orchestre !Camille Sauvage : Il n’est pas dans notre intention de créer la polémique, mais il est permis, n’en déplaise à plus d’un amateur – et l’on pense surtout aux “intégristes” -, de classer l’orchestre de Camille Sauvage dans les orchestres de jazz-swing. D’ailleurs ce musicien, diplômé du Conservatoire de Paris a commencé dans le classique, comme violoniste. Il apprend le saxophone et la clarinette et on le trouve chez Raymond Legrand en 1943-1944. Il joue dans des orchestres de jazz avant la fin de la guerre, par exemple chez Michel Warlop, et l’orchestre qu’il fonde en 1946 s’intitule sur les pochettes des disques Odéon : “Camille Sauvage et son orchestre jazz” ! Sérieusement, on doit reconnaître au clarinettiste-chef d’orchestre, une indéniable qualité d’arrangeur, d’abord dans le jazz, puis dans la musique de danse et de variété vers la fin des années 40, puis pour la radio, la télévision et le cinéma. Il fera de fréquentes saisons dans les casinos français, tels le “Palm-Beach” à Cannes, et le “Bellevue” à Biarritz. Ses interprétations jazz se trouvent sur les marques Odéon, puis Pacific.

Les orchestres de Music-Hall

La France s’est depuis les années 20, intéressée aux orchestres de Music-Hall à consonance jazz. Cela a commencé avec l’orchestre Grégor, qui utilisait beaucoup de musiciens de jazz, mais avait inauguré l’introduction de morceaux de variétés dans son répertoire. Depuis, ce genre d’orchestres a proliféré. On ne parlera toutefois pas de Roland Dorsey, Jo Bouillon, Fred Adison ou Raymond Legrand, bien qu’ils eurent une grande importance. Mais à la fin des années 40 et dans les années 50, Ray Ventura et Jacques Hélian furent quasiment les seuls à enregistrer du jazz-swing, même si Fred Adison était parfaitement capable d’en jouer de manière convaincante, ainsi que l’auteur de ces lignes peut en témoigner. Mais aucun enregistrement vraiment jazz de cet ensemble n’a été trouvé à l’époque qui nous intéresse. Concentrons-nous donc sur les deux mentionnés.Ray Ventura : Tout le monde connaît Tout va très bien, Madame la Marquise, mais ce n’est pas pour cela que cet orchestre figure dans le présent coffret. Il est vrai que Raymond Ventura a commencé très tôt, dans le jazz pur de l’époque, c’était la fin des années 20 et l’orchestre s’appelait “Les Collégiens” parce que les musiciens venaient du lycée Janson-de-Sailly ! Assez rapidement, Ray Ventura prends le leadership de la formation et commence à diverger vers la variété, ce qui fera fuir le saxophoniste Eddie Foy, membre de la première heure. Beaucoup de musiciens de jazz passeront dans son orchestre, citons les trompettistes Philippe Brun, Pierre Allier et Noël Chiboust, les saxophonistes Alix Combelle et Jacques Hélian, le contrebassiste Louis Vola, qui fut longtemps le bassiste du Quintette du Hot-Club de France avant guerre.

Pendant l’occupation, certains membres faisant partie d’une communauté recherchée par les Nazis, l’orchestre arrive à partir en Amérique du Sud, c’est là que débute un certain Henri Salvador, qui fera beaucoup parler de lui au cours des cinquante années qui suivront. A son retour en France, Ray Ventura, nullement découragé de devoir repartir quasiment de zéro, fonde un nouvel orchestre qui utilisera les compétences d’un musicien très talentueux, clarinettiste, saxophoniste et surtout excellent arrangeur, Gérard Lévècque, qui avait lui aussi joué dans le quintette du Hot-Club de France, mais celui de l’occupation, avec clarinette. Ce musicien passera ensuite chez Jacques Hélian. Entre 1946 et 1948, l’orchestre Ray Ventura aura une activité intense, que ce soit des galas, des enregistrements, souvent avec Henri Salvador, ou qu’il s’agisse de sa participation au film “Nous irons à Paris”. Si l’orchestre ne courait pas les bals, il enregistrait néanmoins pour la danse et jouait donc des swings avec beaucoup de conviction. L’importance de Ray Ventura décroîtra dans les années 50 : on ne dira plus “Sacha Distel, c’est le neveu de Ray Ventura”, mais “Ray Ventura, c’est l’oncle de Sacha Distel”. Ainsi tourne la roue !Jacques Hélian : Il démarre en 1932 comme musicien de jazz, joue chez Roland Dorsey et commence à être connu comme saxophoniste de Ray Ventura juste avant la guerre, mais la grande aventure ne commence qu’à son retour de captivité. Sur le conseil de Ray Ventura, il fonde un orchestre en 1945, qui va personnaliser la joie de vivre à la fin de la guerre : C’est une fleur de Paris détrône presque La Marseillaise !

Pour des raisons de contrat, l’orchestre enregistre tout au début sur une marque belge sous le nom de Charley Bazin, avec déjà André Cornille à la trompette et Christian Garros à la batterie, mais les choses évoluent vite et l’on a bientôt un bel orchestre de variétés comprenant de nombreux musiciens de jazz parmi lesquels Gérard Lévècque aux anches, Ladislas Czabanyck ou Paul Rovère à la contrebasse et bientôt Ernie Royal en personne à la trompette (mais seulement pour le jazz !), Bill Tamper au trombone, Pierre Guyot au piano, Pierre Gossez et Georges Grenu aux saxes, Sadi au vibraphone, Marcel Bianchi à la guitare, Armand Molinetti à la batterie, qui sera suivi un peu plus tard par Kenny Clarke, tout heureux semble-t-il de jouer dans l’orchestre. Certes, la formation de Jacques Hélian n’était pas une formation de jazz, mais quand le chef décidait de jouer 20 minutes de jazz-swing au milieu d’un concert, le doute n’était pas possible, les thèmes étaient du genre In The Mood ou Caravan avec un Christian Garros déchaîné, ça sonnait vraiment 100 % jazz5. L’orchestre régulier s’arrêtera en 1957, lorsque Jacques Hélian aura des problèmes graves de santé, qui limiteront fortement son activité, et le forceront à employer sporadiquement des orchestres composés pour la circonstance.

Orchestres de danse d’après guerre

Il n’est pas possible de détailler tous les orchestres qui officièrent après la guerre, il y en avait partout, c’était la joie d’être en paix, et il faut aussi avouer que l’on manque terriblement d’information sur la plupart d’entre eux. Michel Ramos est surtout connu pour ses prestations de danse typique au début des années 50, d’excellente qualité d’ailleurs mais étrangères au présent travail. En 1945, on le trouve sur quelques disques Odéon dirigeant un ensemble de saxophones sur des arrangements bien swing. De même, Jean Faustin (ou Faustin Jean-Jean comme on veut), publie sur la même marque quatre morceaux qui mériteraient toutes une réédition de jazz. Il fera beaucoup de danse par ailleurs. Georgie Kay dirige en 1946-1947 l’orchestre du Jazz Club Français, pas étonnant puisque les disques paraissent sur le label ABC Jazz Club du Jazz Club Français précisément. Il changera de nom quelques années plus tard et s’appellera “Los Camagueyanos” pour jouer des sambas ! Plus consistant, l’orchestre de Sébastien Solari est une formation imposante, qui comprend Max Adreit au trombone, William Boucaya au saxo-baryton, Willy Lockwood au saxo-ténor et Arthur Motta à la batterie. S’il a fait surtout des rumbas, des sambas et des mambos6, il a fait aussi quelques excellents morceaux swing7. Eddie Barclay : Au début des années 40, Edouard Ruault (le vrai nom d’Eddie Barclay) est un pianiste de jazz, qui enregistre en particulier avec Hubert Rostaing. Après la guerre, il fonde la marque de disques Blue Star, pour concurrencer a-t-on dit la marque Swing de Charles Delaunay. Il fonde aussi une autre marque principalement pour le typique, Riviera. Ce n’est que quelques années plus tard qu’il forme un orchestre de variété qui aura son heure de gloire. Il y a de temps en temps un morceau de simili-jazz, mais par contre, en 1957, il frappe un grand coup en enregistrant un disque, avec des titres de variété, mais comprenant un contingent prestigieux de musiciens de jazz : Stéphane Grappelli au violon, Raymond Guyot à la flûte, Don Byas et Lucky Thompson au saxo-ténor et Kenny Clarke à la batterie, les arrangements étant de Quincy Jones. Les thèmes sont tous des “medium-fox”, le disque ayant été fait pour danser, mais ça swingue !

Au fil des interprétations, de 1945 à 1957

Les disques 78 tours de Surprise-Partie ont constitué l’essentiel de la source utilisée pour le présent coffret. Il va sans dire, tout le monde le comprendra, que ces disques sont pour la plupart usés ou cassés, quand ils ne sont pas définitivement perdus. Optimiser le contenu musical de la présente édition a donc consisté, non seulement à chercher les meilleurs morceaux swing encore trouvables, mais aussi les disques les moins outragés par une utilisation un tantinet négligente. Le report et le nettoyage musical de certains disques a constitué le plus gros du travail de mise sur CD et le résultat dans quelques cas n’est pas au niveau de qualité qu’on aurait souhaité. Mais l’intérêt musical et la rareté sont passés en premier. Tous les morceaux ont été soigneusement remis à la bonne tonalité. Il est aussi nécessaire de préciser que les disques de surprise-partie ne comportent la plupart du temps aucun renseignement discographique. Comme les orchestres swing, devenus des orchestres de variétés, sont presque totalement absents des discographies de jazz, les renseignements concernant les interprétations sont souvent sommaires. Heureusement qu’il y a encore quelques précieux documents gardés par des collectionneurs impénitents ! Qu’ils en soient remerciés.

Les amateurs de jazz purs, dont beaucoup seront certainement intéressés par le présent coffret, excuseront la lourdeur de certains batteurs, il n’y avait pas en France au sortir de la guerre de challengers pour Chick Webb ! On écoutera plutôt les arrangements souvent brillants, quelquefois surprenants et en général bien interprétés, avec souvent de bons solis le plus souvent anonymes.On appréciera pour commencer un morceau parfaitement jazz, interprété par Christian Bellest quelques jours avant l’Armistice. Il faut dire qu’à cette époque, l’orchestre de Glenn Miller était à Paris – sans son chef, malheureusement disparu au moment où l’orchestre arrivait en France depuis l’Angleterre en Décembre 1944. Mais l’excellence de cette phalange, habituée à jouer avec les mêmes musiciens depuis presque deux ans et très bien dirigée par l’arrangeur Jerry Gray et le batteur Ray McKinley, constituait un modèle quasiment inaccessible pour les musiciens français. Dans cette ambiance, Christian Bellest s’en sort très bien avec Rockin’ The Blues, de Count Basie. A peu près à la même époque, Michel Ramos, dans Delhi et Swing en sol, fait encore preuve d’une esthétique héritée de l’occupation. Pierre-Sèverin Luino, entre deux danses à la mode, se paye un swing Torpedo Junction, il ne devait pas y en avoir beaucoup à la “Coupole”, qui avait plutôt la réputation de donner dans le tango et la rumba ou la biguine, c’est qu’on était à Montparnasse ! Le premier orchestre d’après-guerre de Jacques Hélian (placé sous la direction de Charley Bazin comme on l’a vu) avec Asking For Swing fait déjà preuve d’un niveau déjà très honorable, et on peut saluer, toujours en 1945, les efforts plus modernes de Jean Faustin dans Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t, morceau que venait de jouer quelques mois plus tôt Glenn Miller dans ses émissions à l’intention des soldats allemands pour les décourager de continuer à se battre !

1946 est l’année où les enregistrements de musique de danse démarrent vraiment et les orchestres swing sont à l’honneur. Cela commence avec Ray Ventura, qui se permet d’enregistrer Caldonia de Woody Herman, bien connu, mais aussi un morceau qui l’est beaucoup moins, That’s The Moon My Son, vaguement yiddish, avec un passage de trompette “à la Ziggy Elman” et une fin très Sing Sing Sing de Benny Goodman, on ne se refuse rien ! Avec un orchestre digne des formations américaines, où son jeu au saxo-alto fait merveille, Hubert Rostaing joue November Blues, puis On The Sunny Side Of The Street venu tout droit d’Outre-Atlantique. Plus original, Buffalo est un obscur morceau qui permet à notre musicien de “recréer” (partiellement) le concerto de clarinette d’Artie Shaw, qu’il interpréta à la même époque avec l’orchestre de Jacques Hélian. Au même moment, Ray Ventura retrouve une vitesse de croisière, où Undecided (du trompettiste américain Charlie Shavers) et In The Mood (dans un arrangement original qui change un peu des interprétations “à la Glenn Miller”) côtoient Monsieur de la Palisse et Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway ! Camille Sauvage enregistre depuis déjà plus d’un an sur Odéon, Claridge fait partie avec Carlton et Bristol, d’une série de morceaux dédiés à des hôtels de luxe. Enfin Tony Proteau, au cours d’une de ses trop rares sessions, enregistre Shoo Fly Pie sur Blue Star, avec la chanteuse Nell Evans. Le verso de cette interprétation, Blue Feeling Blues, se trouve sur le coffret “Swing in Europe, The Big Bands 1933-1952”, FA 5112.1947 voit l’apparition du saxophoniste alto André Ekyan avec un big band : I Should Care a été sélectionné pour le très beau solo du chef, alors que Mop-Mop et Perdido sont destinés à montrer la qualité de l’orchestre.

Il ne faut pas confondre ce Mop Mop avec le morceau américain de même intitulé qui avait été interprété par Coleman Hawkins en 1943. Ce très bel ensemble du saxophoniste s’est rapidement consacré à des interprétations de variété ou de danse typique. André Ekyan ne fera plus ensuite qu’une seule session de jazz, et en petite formation. L’orchestre du Jazz Club français n’est pas un monstre de swing, son saxophoniste Jean Ledru était ingénieur, mais il allait jouer les Samedi soir en 1951-52 avec l’orchestre de Maurice Emo au “Kentucky”, un petit club de la rue des Carmes, devenu ensuite “Chez Alex”, pour finir en laverie ! On peut danser gentiment sur The Sergeant Was Shy, un morceau de Duke Ellington, pas moins ! Noël Chiboust inaugure avec Black Swing une nouvelle marque de disque, Selmer. En 1947, Maurice Moufflard se fait connaître du grand public avec une formation très étoffée où l’on note la présence du jeune William Boucaya au baryton, probablement un de ses premiers enregistrements. Les morceaux sont résolument tirés du répertoire américain : Cement Mixer, de l’inénarrable Slim Gaillard, mais aussi Hamp’s Boogie-Woogie, où il faut reconnaître que le chef a visé un peu haut, mais en tout cas, ils se sont bien amusés ! Fernand Clare aime aussi interpréter des succès américains, témoin ce Leave Us Leap qui s’efforce de se hisser au niveau du même morceau par Gene Krupa. Dommage que le batteur, emporté par son élan, ne sauvegarde pas cette petite seconde de silence à la fin du morceau, enfin ça swingue et c’est le principal !

On Basie Street d’Aimé Barelli sonne vraiment bien, l’orchestre commençant à s’étoffer. Jungle Tom de Sébastien Solari fait penser qu’il s’agit d’un orchestre de jazz chevronné, alors que ce n’est qu’un orchestre de danse relativement nouveau, où l’on entend le saxophoniste baryton William Boucaya à la clarinette. L’orchestre de Camille Sauvage est à son mieux dans la dernière interprétation swing sur Odéon Martini Gin, il va incessamment passer sur Pacific où il continuera à jouer des morceaux de son cru, qui portent parfois des titres curieux, tel Week-end dans les oubliettes dont le début fait vaguement penser au Nightmare d’Artie Shaw. Au verso de ce morceau, on trouve Radiesthésie et mèche de cheveux...Qui trouve mieux ?Au tournant des années 40 à 50, on sent que les orchestres disposent de plus de moyens, les sections s’étoffent et l’influence des nouveaux orchestres swing américains, genre Woody Herman ou Stan Kenton se fait sentir. L’orchestre du “Lido”, emmené par René Leroux, est solide, même si le thème interprété, Toolie Oolie Doolie est relativement commun. Il est temps de ralentir un peu le tempo, Aimé Barelli nous délivre un joli slow sur Les feuilles mortes (Autumn Leaves), le chef d’œuvre de Joseph Kosma, ici interprété de façon instrumentale. A peu prés à la même époque, est sorti le film “Les Joyeux Pèlerins” où l’on peut entendre Aimé Barelli jouer son Blues 50 dans une version différente de celle du disque 78 tours, sous l’œil d’abord soupçonneux de Pasquali, qui finalement va trouver la prestation géniale !

C’est la grande époque pour Jacques Hélian, le trompettiste afro-américain Ernie Royal enflamme l’orchestre avec Always, un grand favori des musiciens de jazz. Noël Chiboust ne s’en laisse pas compter : après Selmer, il passe fugitivement chez Riviera et son Récréation fait revivre les grands moments chez Swing, avec un solo de clarinette au style un peu modernisé. Tout ça (Count Every Star) permet de se relaxer un peu après l’effort ! Il est un peu du genre “Vous habitez chez vos parents ?” mais il faut reconnaître que Chiboust a bien assimilé et “francisé” le style si particulier de Glenn Miller.C’est alors une suite ininterrompue de morceaux des anciens grands du jazz français avec leurs orchestres de danse : Jerry Mengo avec Un p’tit coup de chapeau merci Jerry, puis Philippe Brun, un peu en retrait avec une formation pas très importante, mais on n’a rien trouvé d’autre, qui joue Bravo, un thème rapidement oublié mais ça n’est pas grave. Aimé Barelli nous gratifie de ce qui peut être considéré comme son dernier disque 78 tours de vrai jazz, Thème 52, arrangé comme il se doit par Armand Migiani qui se sent nettement démangé par ce qu’on appelait encore le re-bop. Alix Combelle est en excellente forme chez Vogue, même si les morceaux interprétés sont assez “commerciaux”, mais C’est bon de rêver comporte un re-recording de la voix du chef qui laisse supposer qu’ils étaient trois, mais non il n’y a que notre Alix ! Les deux autres morceaux Missié Ropein et Captain Cook’s Tour, avec son démarrage à la String of Pearls, sont plus sérieux et peuvent être considérés comme la crème chez Vogue. Moonlight Serenade recrée l’atmosphère de l’immédiat après-guerre, quand l’orchestre de l’Army Air Force de feu-Glenn Miller était à Paris, mais attention, ce n’est plus un slow mais un swing féroce, au fond pourquoi pas ?

Le Lucifer de Noël Chiboust est un morceau swing typique de ce musicien, perdu au milieu des faces de variété, il n’y aura ensuite plus de swing vraiment jazz avec cet orchestre. Il est rare d’entendre Nuages de Django Reinhardt en big band : Hubert Rostaing s’y essaie avec succès, avec des glissandos de saxophone “à la Billy May” et un beau solo de guitare d’Henri Crolla. Là aussi, comme pour la plupart des autres orchestres, c’est une face jazz un peu noyée au milieu des faces de variété. On retrouve Jerry Mengo, d’abord chez Ducretet-Thompson avec Jerry’s Boogie, puis chez RCA, où il aime enregistrer des succès américains tel Opus #1, mais aussi En écoutant mon cœur chanter, que les Américains ont appelé All Of A Sudden My Heart Sings.On termine avec quelque chose d’unique : un orchestre de variétés comprenant de grands musiciens de jazz, jouant Avec ces yeux-là de Michel Legrand, un thème de variété dans un style résolument jazz, avec un solo de Lucky Thompson, on croirait rêver. C’est vrai d’ailleurs, on a rêvé depuis deux heures, on était sur un nuage qui s’éloigne de plus en plus et qui a presque disparu à l’horizon. Vous n’y avez peut-être pas pensé, mais il est encore temps de danser un petit swing, ça changera un peu de l’electro-jazz, allez allez, rappelez-vous ou demandez à vos parents ou à vos grands-parents !

Pierre CARLU

Remerciements à Jean-Claude Alexandre, Henri Merveilleux, Daniel Nevers et Alain Tercinet.

© Frémeaux & Associés

1. voir volume 12 de l’“Intégrale Django Reinhardt” (FA 312)

2. voir volumes 6, 9 et 10 de l’“Intégrale Django Reinhardt” (FA 306, 309 et 310)

3. voir volumes 7 et 9 de l’“Intégrale Django Reinhardt” (FA 307 et 309)

4. Renseignements fournis par Daniel Nevers, à partir d’un texte de Gérard Roussel

5. L’auteur de ces lignes peut en témoigner

6. voir le coffret “Mambos à Paris 1949-1953” (FA 5132)

7. on peut en entendre un, Saturday Afternoon, dans le coffret “Swing In Europe big Bands 1933-1952” (FA 5112)

english notes

Postwar Swing Bands in Paris

1945-1957

The end of the French swing bandsThe Armistice of May 1945 brought an end to five years of horror. Life in France could go on as before. Really? History would not repeat itself. The events leading up to the war belonged to the past and, obviously, the French had no desire to live through another 1940. Of course, there were no sudden changes. The Occupation had seen the development of a jazz style that swung determinedly; it had appeared shortly before the war, and the five-year period of isolation in which the French had found themselves was an encouragement for «swing jazz» to prosper. There was nothing unusual in that: in Paris, at least, the style allowed a change of mood. Let’s not forget that Swing — initiated pre-war in The United States — was based on a form of big-band jazz that suited casinos and palaces; it was «festive» music, and therefore especially suited to the ears of poor people who’d suddenly woken up to the sound of marching boots.At the end of the hostilities, jazz, and therefore Swing, triumphed. On the swing record-label, Noël Chiboust celebrated the Americans’ arrival with a vibrant Welcome1. And Aimé Barelli, Alix Combelle, Django Reinhardt, Hubert Rostaing etc. were right up there alongside him.But, as we’ve said, there’s an end to everything. So what happened next? Well, American records reappeared, albeit gradually. And what could be heard on them? Music that had nothing whatever to do with the Swing sounds of the late Thirties.

With France still in the throes of the Occupation, jazz had been evolving in The United States; the French discovered a brand-new world of music on the first records brought to France by Charles Delaunay (whose aptly-named swing label had been kept busy throughout the Occupation with imports of all the swing-band recordings). The new records available caused the French to discover two musicians who were unknown to them in 1945, but who would definitively change the face of jazz: trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and alto-saxophonist Charlie Parker. It was an excellent opportunity for gifted young musicians to leap into a new jazz era: Michel De Villers, Jean-Claude Fohrenbach, Bernard Peiffer, Hubert and Raymond Fol, Henri Renaud and many others, André Hodeir included, would have the times of their lives, especially after those new-school American musicians took it into their heads to cross the ocean and meet them face to face...And as if that wasn’t enough... In the Latin Quarter of Paris, a band started playing King Oliver’s music again, this time in a cellar: at the «Lorientais», Claude Luter and his band were immensely successful, and the phenomenon was amplified when, a little later, Sidney Bechet moved into Paris and began playing with all these youngsters (and those who came after them). The new climate was radically different from the swing-band atmosphere that reigned under the Occupation; what would be the fate of these new outfits, mostly forgotten by jazz fans, or at least by «purists»?Throwing in the towel was out of the question. Swing had produced a sizeable generation of very good musicians: they were excellent readers and often good soloists, especially the major figures.

All these musicians and their bands had only a single thought: playing. They’d already breathed new life into clubs and dancehalls with a swing that brought many fans to their feet, all of them delighted to let off steam dancing to excellent music. All the bands had to do now was continue, this time with the new South American dances that were coming in: first, bolero (actually a rumba variation), then samba (guaracha, more often than not) and, last but not least, mambo, which the swing bands played better than anyone else, as it demanded a larger ensemble and its music closely resembled swing. Could anyone ask for more? These bands were called «commercial» by some, which wasn’t unreasonable, given that they didn’t play concerts, so much as make dancers dance. But even the best jazz big bands, like those of Chick Webb or Erskine Hawkins, were dance-bands, not concert-bands, and they were commercial... Weren’t they all?So, in the second half of the Forties and throughout the Fifties, swing orchestras not only stayed alive, but the best of them became better, modelling themselves on the great American swing bands of the post-war era led by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and Woody Herman. Some swing bands even sprang up after the war, like Tony Proteau’s orchestra, or the band led by Camille Sauvage, somewhere between dance and jazz but, most importantly, it could really swing! Pure dance-orchestras, inexistent before the war, also appeared; those led by Sébastien Solari or Jean Faustin could swing with conviction, for example. The most persuasive bands, however, were the headliners of the swing era, especially when they moved people to dance what was called the «fox-swing»: the name translated its fox-trot origins — and showed more dynamism — and it also distinguished the style from what they called the «slow-fox», which brought some respite to dancers.

The pieces chosen for this set, needless to say, were predominantly pure, solid swing, although the odd slow number was slipped in here and there to show the orchestra’s talents at a slower tempo. These bands no longer recorded for Swing — unsurprisingly — so they had to change labels and migrate to companies with dance-catalogues; Pathé, Odéon, Polydor, Selmer, Cantoria or Ducretet-Thomson provided a welcome, and here’s the rub: these dance-records were played at parties, not collected so much as left lying around carelessly somewhere, with the result that they were just thrown away when they were too worn to serve their purpose. They rapidly disappeared from record-bins, replaced by the next dance-records to come along. One eloquent example of their fate was the arrival in the Fifties of rock & roll, which literally seized power on the dance-floor at private parties. This was also the age when the great swing bands disappeared entirely from their usual haunts, although there were some (notable) exceptions: Aimé Barelli stayed on at the «Sporting Club» in Monte-Carlo, and Pierre Delvincourt remained at the «Lido» in Paris. I can even remember one band — fifteen musicians — in July 1958, playing swing numbers on the beach in front of the casino in Saint-Jean de Luz, no less. But those were the last rays of the setting sun... So let’s go back to 1945-1957, and the swing-laden atmosphere of the post-war era: in seaside casinos, city-centre brasseries (and in dancehalls everywhere), if there was music playing, it was swing or tango!

The big-bands already active in Occupied France

Five or six orchestras still topped the bills in 1945 after making numerous records for swing during the war; they were ready to continue, but not as «jazz» bands.Aimé Barelli was a musician who’d come to Paris in 1940; he’d begun as a member of Raymond Legrand’s orchestra before joining Fred Adison’s band, both of which were quality «popular» orchestras numbering jazz musicians in their ranks. Barelli played in bands formed by various Adison alumni for recording-purposes (Raymond Wraskoff, «Jazz Victor» etc.) and that was how he came to join the prestige «Jazz de Paris» group led by Alix Combelle. The first band he led was actually called «Aimé Barelli et son orchestre du Jazz de Paris», but he soon found his perfect format: trumpet (himself), plus four saxophonists and a full rhythm-section, all of which provided a big-band sound with only nine musicians. It wasn’t until 1946-1947 that Barelli hired a second trumpet and a fifth saxophone — a baritone — to augment the band’s sound. A string-section was also added for some performances, and then the orchestra grew again to include even more brass instruments. After the war, Aimé Barelli was hired by the club «Sa Majesté» on the Champs-Elysées, but his stay was brief: Barelli soon covered the couple of hundred metres separating the club from the «Ambassadeurs» (today the «Espace Cardin»), and settled in. At the time, there were still numerous jazz pieces in the band’s book, some of them dating back to the Swing era, and Barelli’s orchestra also opened (and closed) the famous «Semaine du Jazz» week organised in May 1948 at the Marigny Theatre by Frank Bauer and Simone Volterra.

Barelli also appeared in a film (made in the very early Fifties) called «Les Joyeux Pèlerins», which had at least the merit of allowing people to hear the excellent jazz piece included in this set. He gave a concert at the Alhambra (1953) which featured several jazz numbers, and his orchestra also provided the music for the «Jazz Variétés» sessions held at the Rex. Barelli’s band was also notable for the presence of three young musicians — pianists Francy Boland and Martial Solal, drummer Roger Paraboschi — who were all «new jazz» players. Aimé Barelli had his own moment, too: on March 30th 1952, Dizzy Gillespie played a concert at the Salle Pleyel and, at the end, Barelli came onstage and sat down in the trumpet-section, letting Dizzy take the lead... in playing two pieces from his big-band repertoire of a few years earlier. It was... huge! In the course of the following years, however, more and more «popular» and «non jazz» dance-pieces crept into the band’s repertoire, although there were some very jazzy swing-pieces from time to time, at least until the band moved to the prestigious «Sporting-Club» in Monte-Carlo. The band sounded fine, largely thanks to an impeccable arranger named Armand Migiani, a baritone-player who also recorded jazz and popular pieces under his own name. The Aimé Barelli orchestra held on until 1986, still at the «Sporting Club»; Barelli finally rolled up his own beach-umbrella in 1995. With the exception of Django Reinhardt (an international star in the Forties), Alix Combelle was no doubt the greatest jazz musician in France during the Swing era. He began his career in the early Thirties and recorded his first solo in 1935 with the «Quintette du Hot-Club de France» (QHCF), then also at its debuts. In 1937 he took part in the first-ever session for the newly-formed swing label, playing alongside Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter and his fellow reed-player André Ekyan; the resulting saxophone-quartet recording left an indelible impression on French jazz. His first session as a leader, fronting his «Hot-Club Swing Stars», took place in 1938; he then joined Fred Adison, and recorded with the «Jazz Victor» group, plus the new band led by Noël Chiboust, Aimé Barelli’s band, Hubert Rostaing, and also with his own band of course.

He was everywhere, in fact, and seen naturally as something like the French King of Swing... with the crowning ceremony being his inauguration as the leader of the famous «Jazz de Paris» group. He went on to lead various formations in the Forties, recording for Swing, Columbia, Vogue (with Buck Clayton and Jonah Jones), Philips, and finally the Club français du disque, by which time he was a regular feature at the «Club des Cinq». In October 1953 he appeared with Lionel Hampton’s orchestra for a memorable concert at the «Théâtre de Paris» but, as was the case with all the others, the Fifties saw Combelle making pop and Latin records too, although he remained faithful to jazz until the end. His last Parisian bookings were at the club «Chez Mimi Pinson». In 1958 he had the chance to play with his old friend Buck Clayton again, but also Vic Dickenson, Stuff Smith and Kenny Clarke: a trace of their meeting remains on record. In 1963 he retired, and opened the «Club de la Tour» in Follainville; poor health interrupted his playing and there was little mention of his name again until his death in 1978.Noël Chiboust was a perfectionist. He began while still a youngster, playing with Ray Ventura’s «Collégiens», the most famous French band of the Twenties and early Thirties, in which Chiboust wielded a violin. A few years later, he was playing trumpet with Michel Warlop, a great jazz violinist, before rejoining Ventura. He could also be heard with Raymond Legrand, and then Jean Tranchant... In a word, he was never out of work.

It would be 1938 before anyone saw him playing saxophone and clarinet, and these instruments remained his favourites. When war came he was playing with Fred Adison (showing genuine talent as his arranger), and his first record leading his own band featured Adison’s pianist, Raymond Wraskoff. Chiboust constantly remodelled his orchestral formats — to keep up with his arranging-gifts — and when the Liberation came he continued playing jazz, but left Swing for Selmer: he, too, followed the trend, introducing pop pieces into his repertoire. He played at the «Schubert» club, changed labels in a move to Ducretet-Thomson, and then gradually moved away from jazz. He continued to lead his own orchestra for several years before abandoning music and retiring to the South of France.Hubert Rostaing was a case apart, in that he was the only jazz musician who continued to record for Swing after the war, and then often with a sextet. He began his career at approximately the same time as Aimé Barelli, and made his Parisian debuts in 1940 at «Chez Mimi Pinson» (where Alix Combelle discovered him playing clarinet and bandoneon!) His clarinet-style certainly owed allegiance to Benny Goodman, but he quickly took up the saxophone — first tenor, then alto in particular — and played with a fluent style in the manner of Woody Herman. He recorded with some of Don Redman’s musicians in 1946, and in 1947 he turned up with Jacques Hélian’s orchestra, playing Artie Shaw’s «Clarinet Concerto», no less. Hubert recorded with Rex Stewart and his band when they were in France in December that year, by which time he had a residency at the «Carroll’s» club. It wasn’t until the Fifties that Rostaing was forced to play anything other than jazz, although his dance-sextet did feature a couple of noteworthy jazz musicians in the shape of American trombonist Nat Peck and drummer «Mac-Kac» Reilles.

Rostaing’s big band had practically ceased playing jazz, but this collection contains a notable exception.André Ekyan was an old hand, with experience going back to the orchestra led by Grégor in the early Thirties. His alto-saxophone style clearly shows the influence of Benny Carter — not the worst model for a reed-player, surely — and Carter accompanies him here on this session for swing with Coleman Hawkins. Ekyan always preferred small groups — cf. his performances with Django Reinhardt2 — and only led a big band from 1947 onwards. With the exception of the latter group’s initial recordings, jazz remained outside its essentially pop/Latin repertoire.Jerry Mengo was a name with a special ring for jazz fans, especially after his return from captivity in 1941 when he took charge of the new version of the «Jazz de Paris» group, whose previous leader Alix Combelle had just departed. But his musical career had begun much earlier, with orchestras neither very «well-known» nor very «jazz»: the bands of Rapha Brogiotti and Serge Glykson. After his stint with the «Jazz de Paris», in which Christian Bellest had replaced Aimé Barelli on lead-trumpet, Jerry Mengo concentrated on small-groups for a while (he’d already led some for Swing during the Occupation), and signed with ABC Jazz Club, a little label set up during the war by Yvonne Blanc. At the end of the war he could be heard at «La Villa d’Este», and then «Chez Carroll’s» and at the «Beaulieu». Mengo didn’t return to a big-band format until the turn of the Fifties, but what a band that was! First for Ducretet-Thomson, then for RCA, Mengo recorded not only original tunes but also «covers» of American hits that swung like the devil. Not much was heard from him later, although in 1973 he did lead another orchestra accompanying the great American trumpeter Bill Coleman.

The later jazz orchestras

Christian Bellest had been solicited by the best swing-bands throughout the Occupation; like Barelli, Bellest had a spell with Fred Adison before joining the «Jazz de Paris» band where, obviously, he was only the second trumpet. But he was the lead-trumpet in the band’s second version led by Jerry Mengo. He would also play with Raymond Legrand, and his style, unfailingly inspired by Barelli, was unmistakeable; it was one of his great qualities, too, in a period when most trumpeters sounded more or less the same. In 1945 Christian Bellest brought a number of excellent musicians together for a Blue Star session that produced four numbers, two of which were definitely jazz pieces. He played in the Lido house-band for a while — René Leroux was its leader after Tony Proteau’s departure — and also with Jacques Hélian and his orchestra in 1956. In the course of the Fifties, Bellest and his orchestra gradually moved away from jazz/swing, playing mainly pop music.Philippe Brun had already been a feature of Grégor’s orchestra — playing in a Bix Beiderbecke style — and come to the attention of jazz critic Hugues Panassié. A few months later he turned up with Ray Ventura’s first «Collégiens», swapping his style for that of Louis Armstrong. Next came a long stint with the British band of Jack Hylton (an orchestra which Panassié, naturally, didn’t like at all), and by the end of the Thirties he’d rejoined Ray Ventura and recorded under his own name (with a large number of Ventura alumni3 including tenor-player Jacques Hélian). Brun spent most of the Occupation years in Switzerland, and only returned to France at the end of the war. He appeared at some of the «Jazz Variétés» concerts at the Rex, but played mostly with dance-bands whose swing pieces were rare (the formation led by M. Philippe-Gérard, for example). With the latter, and also as a leader, he recorded some interesting sides with (probably) drummer Armand Molinetti.

Ill-health gradually forced him away from the scene, and his last appearance came in 1986: the occasion was a celebration, held at the «Bibliothèque Nationale» on the rue Vivienne, in honour of Charles Delaunay (and the donation of his considerable record-collection to that venerable French institution.)Maurice Moufflard occupied the trumpet-chair with Jo Bouillon in particular, but post-war he founded a swing-orchestra — it had quality if not character — and recorded for Selmer, a label devoted to dance-music. In 1949, however, he had the good fortune (or rather, the once-in-a-lifetime absolute luck), to accompany Charlie Parker (yes, Bird, the genius), for one tune during a radio programme. In the Fifties, Moufflard continued playing for dancers, but small groups replaced the full format.Pierre-Sèverin Luino will be remembered by adult/senior French jazz fans as the third trumpet in the «Jazz de Paris» band (Aimé Barelli and Christian Bellest were first and second). This is just another way of saying he was in Fred Adison’s band at the time. Less well-known is the fact that he led his own dance-orchestra at the «Coupole» for an incredible 26 years, from 1948 to 1974. It was a magnificent achievement, even given the context. His recordings as a leader, however, were few.Fernand Clare (Ferdinand Carracilly)4 was the leader of «the band that played like the Americans», as Jack Diéval said in 1946. No other comment is really necessary: the Glenn Miller Orchestra had only just left France. Not only was Clare a gifted musician, but he worked hard too; even if his orchestra wasn’t particularly original, it was professional, and after the war there was high demand for it in the casinos.

Clare actually began as a violinist, also playing drums and accordion, and later he completed his armoury when he took up the saxophone and clarinet; his career centred on the French Riviera, where he made his debuts at the age of sixteen. In 1935 he played at the Grand Casino in Juan-les-Pins, sitting in an orchestra led by American pianist Herman Chittison, and when the whole country suddenly became «Occupied France», he went to Switzerland, where he played with Philippe Brun. On his return in 1945 he founded his own orchestra, playing at the «Ruhl Hotel» in Nice and the «Sporting-Club» in Monte-Carlo, before appearing in Deauville and Paris (The «Olympia», and also during the «Nuit du Jazz» in 1947, where he was a sensation). He recorded for Pacific, Odéon and Cantoria before returning to Nice, where he finished his career at the «Palais de la Méditerranée».Tony Proteau was a young alto-saxophonist whose reed-section joined Claude Dubuc en masse in 1943. All of them turned up again after the Liberation, first co-opted into America’s 7th Army, then in the French Air Force. It was his «Collège Rythme» band (first led by saxophonist René Leroux before he handed over to Proteau) that saw the original group transformed into a beautiful big-band; it finally received its just reward when the «Lido» hired them all (on June 20th 1946), thereby guaranteeing the reputation of the prestige Champs-Elysées venue. The group you can hear on its Blue Star sides was already a very modern big band; in 1948 Proteau entrusted René Leroux with its leadership, and the latter remained in charge until bassist Pierre Delvincourt took over in 1953.

During this period, Proteau, who wanted to play nothing but jazz, founded yet another band. This one appeared at Pleyel during the 1949 «Festival de Jazz» (organised by Charles Delaunay), only to be booed off-stage5 by jazz «fundamentalists» who couldn’t bear a band that still had time for Woody Herman. Proteau also livened up some of the «Jazz Variétés» sessions, accompanying Sidney Bechet and Django Reinhardt among others. Later, of course, he fell into line and began recording pop material... His disappearance from the French jazz scene was a crying shame, because he really knew how to lead a band!Camille Sauvage can be included in the swing/jazz category — probably to the dismay of some of the above-mentioned purists — although that statement shouldn’t be taken as controversial. Sauvage attended the «Conservatoire de Paris» as a classical musician, a violinist, and he studied the saxophone and the clarinet before appearing in Raymond Legrand’s orchestra in 1943-1944. By the time the war ended he’d played with other jazz bands — with Michel Warlop for example — and also with the orchestra he’d set up in 1946, referred to on the sleeves of his Odéon records as «Camille Sauvage et son orchestre jazz». More seriously, this clarinettist-bandleader deserves recognition for his qualities as an arranger: first in jazz, then in dance- and pop-music at the end of the Forties, and later in radio, television and films. He played for many seasons at French casinos such as the «Palm-Beach» in Cannes, the «Bellevue» in Biarritz, etc., and his jazz performances appeared on records for Odéon and Pacific.

The Music-Hall Orchestras

France had shown an interest in «jazzy» music-hall orchestras since the Twenties, an interest that began with Grégor, who hired many jazz musicians. Grégor, however, also introduced a trend that saw pop-music pieces gain increasing importance in the big-band repertoire; similar groups proliferated — led by Roland Dorsey, Jo Bouillon, Fred Adison or Raymond Legrand — but, whatever their importance at the time, they don’t really deserve more than a passing mention here. At the end of the Forties and throughout the Fifties, Ray Ventura and Jacques Hélian were almost the only bandleaders who made swing-jazz records, even if Fred Adison was equally as good (as I can personally testify). No real jazz recording made by the latter has come to light, however, so here we can concentrate on Ventura and Hélian.Ray Ventura is famous for Tout va trés bien, Madame la Marquise, but that’s not the reason why his orchestra is featured in this set. Raymond Ventura began very early on, playing the pure jazz of this era; it was in the late Twenties, and his band was called «Les Collégiens» because all its musicians were still in High School (at the «Lycée Janson-de-Sailly»)!

Ray Ventura quickly took charge and began investigating pop music, which caused one of the group’s early mainstays, saxophonist Eddie Foy, to flee from the band. Among the many jazz musicians who passed through its ranks were trumpeters Philippe Brun, Pierre Allier and Noël Chiboust, saxophonists Alix Combelle and Jacques Hélian, and bassist Louis Vola, who was with the QHCF for a long time before the war. Some members of the band had ties with a group of people actively sought by the Nazis during the Occupation, and the orchestra managed to head for South America; incidentally, their destination saw the debuts of one Henri Salvador, a singer-songwriter who was to make something of a name for himself over the next five decades... On his return to France, Ray Ventura — he wasn’t in the least discouraged by having to start all over again — founded a new orchestra, which made excellent use of the talents of a musician named Gérard Lévècque, a gifted clarinettist, saxophonist and brilliant arranger who had also played clarinet with the QHCF (in its Occupation version). He later joined Jacques Hélian. Ray Ventura kept very busy from 1946 to 1948, playing concerts and recording (often with Salvador), and also appearing in the film «Nous irons à Paris». Even if the band didn’t work the dance-halls, it still recorded music for dancing, and therefore swing-pieces, with great conviction. Ventura’s importance declined in the Fifties: people no longer said, «Sacha Distel? Isn’t he Ray Ventura’s nephew?», but rather, «Ray Ventura? Wasn’t he Sacha Distel’s uncle?» Times had changed.Jacques Hélian began as a jazz musician in 1932 with Roland Dorsey, and drew attention as Ray Ventura’s saxophonist just before the war. But his adventures really began when he returned from captivity.

Taking Ventura’s advice, he set up his own orchestra in 1945 and it became a symbol for the joie de vivre that reigned immediately after the war: the band’s tune C’est une fleur de Paris almost dethroned La Marseillaise! For contractual reasons, Hélian’s first records appeared (on a Belgian label) under the name «Charley Bazin»; trumpeter André Cornille and bassist Christian Garros were already in the band, but it quickly evolved into a first-rate popular orchestra that featured many jazz musicians, among them reed-player Gérard Lévècque, Ladislas Czabanyck or Paul Rovère on bass, and soon none other than Ernie Royal on trumpet (only for the jazz numbers!) Others included Bill Tamper on trombone, Pierre Guyot on piano, saxophonists Pierre Gossez and Georges Grenu, Sadi on vibraphone, guitarist Marcel Bianchi and drummer Armand Molinetti, whose shoes were later filled by a certain Kenny Clarke who, to all accounts, was delighted to play behind such a band. Jacques Hélian’s orchestra wasn’t nominally a jazz band, of course, but in mid-concert, when its chief suddenly decided to let loose with 20 minutes of swinging jazz, no doubt remained as to their music’s true nature: with titles like In The Mood or Caravan (a wild feature for Garros), the band sounded nothing less than 100% jazz5. The regular group disbanded in 1957 (Jacques Hélian had to seriously reduce his activity due to health-problems; his later appearances were sporadic, each time fronting a pick-up band chosen specially for the occasion).

The post-war dance orchestras

A list of all the orchestras which officiated in the post-war years would be impossible, because there were bands everywhere — there was joy in peacetime — and, admittedly, hardly any information is available where most of these formations are concerned. Michel Ramos was known for the (excellent) dance-numbers he played in the early Fifties, but they fall outside the scope of this set; he made a few records for Odéon in 1945 leading a saxophone ensemble which played good swing arrangements. As for Jean Faustin (or Faustin Jean-Jean, if you prefer), he released four pieces for the same label that are all worthy of a jazz reissue; his other work relied on dance-numbers. From 1946-47, Georgie Kay led the «Jazz Club Français» Orchestra; unsurprisingly, since its records appeared on the ABC Jazz Club label which belonged to the... «Jazz Club Français». The band changed its name a few years later to «Los Camagueyanos» (they played sambas!) A more consistent band was Sébastien Solari‘s orchestra, which featured Max Adreit on trombone, William Boucaya on baritone saxophone, Willy Lockwood on tenor, and drummer Arthur Motta; even though they played mostly rumbas, sambas and mambos6, their repertoire also included excellent swing pieces.7 Eddie Barclay (his real name was Edouard Ruault) was a jazz pianist in the Forties, and he recorded with Hubert Rostaing in particular. After the war he founded Blue Star Records — it’s said he did so to compete with Charles Delaunay’s Swing label — and also Riviera, a label concentrating more on Latin music. Barclay didn’t get his own orchestra together — the pop variety — until several years later, and it was quite a successful venture: now and again there was a jazzy piece, but he was right on target in 1957 when he did a pop record with a prestigious contingent of jazz musicians: Stéphane Grappelli played violin, with Raymond Guyot on flute, Don Byas and Lucky Thompson on tenor saxophones, Kenny Clarke on drums, and the arrangements were written by a certain Quincy Jones... All the tunes were in what they called the «medium-fox» vein, because it was a dance-record, but it swung like mad.

Tracknotes, recordings 1945-1957