- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

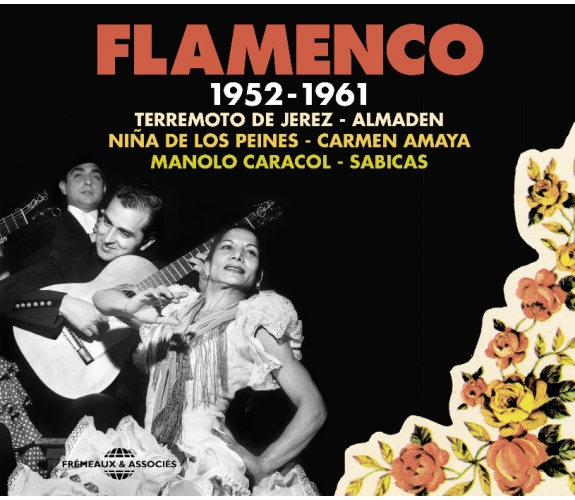

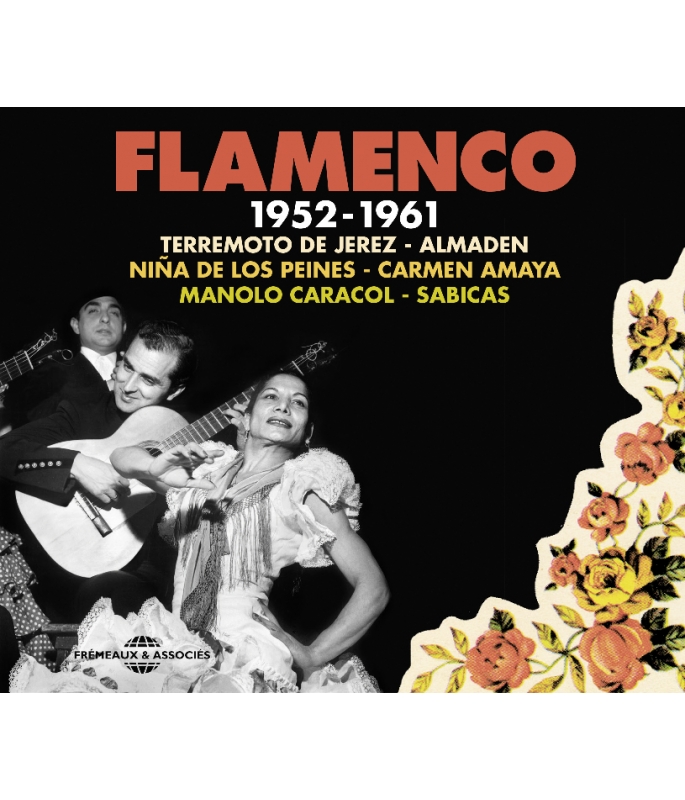

TERREMOTO DE JEREZ - EL NINO DE ALMADEN • NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • CARMEN AMAYA • MANOLO CARACOL • SABICAS...

Ref.: FA5448

EAN : 3561302544823

Direction Artistique : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

TERREMOTO DE JEREZ - EL NINO DE ALMADEN • NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • CARMEN AMAYA • MANOLO CARACOL • SABICAS...

- - Recommandé par France Musique (Musique Emoi)

« Musique populaire au sens noble du terme, le flamenco est issu du brassage culturel de l’Andalousie.

Cette anthologie démontre qu’il est bien l’expression d’une tradition collective dont l’idéal a été sublimé par des chanteurs comme Manolo Caracol, Terremoto de Jerez ou Niña de los Peines et des guitaristes comme Melchor de Marchena ou Sabicas.

L’Espagne, dans toute sa richesse arabo-judéo-chrétienne et gitane, affirme ici son statut de précurseur dans la world music. »

Philippe LESAGE

“As “popular music” in the noble sense, flamenco was born out of the cultural mix which developed in Andalusia.

This anthology shows that flamenco is indeed the expression of a collective tradition whose ideal was sublimated by such singers as Manolo Caracol, Terremoto de Jerez or Niña de Los Peines, and guitarists like Melchor de Marchena or Sabicas.

Here, the full musical richness of Spain — Arab, Judaeo-Christian and gypsy — affirms its status as a World Music precursor.”

Philippe LESAGE

DIR. ARTISTIQUE : TECA CALAZANS ET PHILIPPE LESAGE

DROITS : DP / FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

CD 1 : • MEDIAS GRANAINAS Y GRANAINAS NIÑO DE ALMADEN • A MI MARE ABANDONE NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • ME PUEDEM MANDAR MANOLO CARACOL • EL RENIEGO MANOLO CARACOL • SOY PIEDRA Y PERDI MI CENTRO NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • SIEMPRE ESTOY SOÑANDO TERREMOTO DE JEREZ • SOLEARES SABICAS • MALAGUEÑA SÉVILLANS INCONNUS • EN EL CALABOZO MANOLO CARACOL • TOITA AGUA DEL MAR FOSFORITO • BULERIAS JUANA MORALES • NO QUIERO NA CONTIGO MANOLO CARACOL • RECUERDO A CARMEN AMAYA SABICAS • GARROTIN CARMEN AMAYA • FANDANGOS DE HUELVA ROQUE MONTOYA / JARRITO • ANTES DE LLEGAR A TU PUERTA MANOLO CARACOL • QUE DEL NIO LA COGI MANOLO CARACOL • CUANDO DE VAYAS CONMIGO MANOLO CARACOL • TONÁS RAFAEL ROMERO • MARTINETES RAFAEL ROMERO. •

CD2 : • GYPSY DANCE PASTORA AMAYA AND FRIENDS • BULERIAS ROQUE MONTOYA / JARRITO • EN LA PUERTA CON TU MADRE TERREMOTO DE JEREZ • SE LA LLEVO DIOS MANOLO CARACOL • MALAGUEÑAS NIÑO DE ALMADEN • AL CIELO QUE ES MI MORADA NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • A QUE NEGAR EL DELIRIO NIÑA DE LOS PEINES • GITANERIA ARABESCA NIÑO RICARDO • SAETAS LOLITA TRIANA ET ROQUE MONTOYA / JARRITO • RIPE GRAPES STREET CRIES OF SEVILLE • DEBAJITO DEL PUENTE MANOLO CARACOL • TIENTOS NIÑO DE ALMADEN • VERDIALES BERNARDO EL DE LOS LOBITOS • SEVILLANAS CORREALES BERNARDO EL DE LOS LOBITOS • ALEGRIAS PERICON DE CADIZ • SOLEARES PEPE DE LA MATRONA • CANTES DE TRILLA BERNARDO EL DE LOS LOBITOS • PETENERA RAFAEL ROMERO • NANAS BERNARDO EL DE LOS LOBITOS • GYPSY LULLABYE PASTORA AMAYA.

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Medias granainas y granainasNino de AlmadenPopulaire00:04:161954

-

2A mi mare abandoneNina de los PeinesE. Duran00:02:591950

-

3Me puedem mandarManolo CaracolPopulaire00:04:401958

-

4El reniegoManolo CaracolPopulaire00:05:061958

-

5Soy piedra y perdi mi centroNina de los PeinesE. Duran00:02:481950

-

6Siempre estoy sonandoTerremoto de JerezMonge00:06:331956

-

7SolearesSabicasCastillo00:03:081961

-

8MalaguenaSevillans inconnusPopulaire00:03:331952

-

9En el calabozoManolo CaracolPopulaire00:01:471958

-

10Toita agua del marFosforitoAntonio Fernandez00:03:311957

-

11BuleriasJuana MoralesPopulaire00:03:071952

-

12No quiero na contigoManolo CaracolPopulaire00:03:501958

-

13Recuerdo a carmen amayaSabicasCastillo00:03:011958

-

14GarrotinCarmen AmayaAmaya00:05:291958

-

15Fandangos de huelvaRoque Montoya / JarritoPopulaire00:02:531954

-

16Antes de llegar a tu puertaManolo CaracolPopulaire00:02:261958

-

17Que del nio la cogiManolo CaracolPopulaire00:04:181958

-

18Cuando te vayas conmigoManolo CaracolPopulaire00:02:231958

-

19TonasRafael RomeroPopulaire00:01:321954

-

20MartinetesRafael RomeroPopulaire00:02:531954

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Gypsy dancePastora Amaya and friendsPopulaire00:03:181952

-

2BuleriasRoque Montoya / JarritoPopulaire00:02:241954

-

3En la puerta con tu madreTerremoto de JerezPopulaire00:03:001956

-

4Se la llevo diosManolo CaracolPopulaire00:03:591958

-

5MalaguenasNino de AlmadenPopulaire00:05:401954

-

6Al cielo que es mi moradaNina de los PeinesCallejon00:02:521950

-

7A que negar el delirioNina de los PeinesMontes Y Torres00:02:551950

-

8Gitaneria arabescaNino RicardoRicardo00:03:051955

-

9SaetasLolita Triana / Roque Montoya / JarritoPopulaire00:09:051954

-

10Ripe grapesStreet Cries of SevillePopulaire00:01:061952

-

11Debajito del puenteManolo CaracolPopulaire00:02:241958

-

12TientosNino de AlmadenPopulaire00:04:001954

-

13VerdialesBernardo el de los LobitosPopulaire00:03:041954

-

14Sevillanas correalesBernardo el de los LobitosPopulaire00:02:591954

-

15AlegriasPericon de CadizPopulaire00:02:571954

-

16SolearesPepe de la MatronaPopulaire00:03:261954

-

17Cantes de trillaBernardo el de los LobitosPopulaire00:01:401954

-

18PetenerasRafael RomeroPopulaire00:03:361954

-

19NanasBernardo el de los LobitosPopulaire00:03:291954

-

20Gypsy lullabyePastora AmayaPopulaire00:02:091952

Flamenco FA5448

CLIQUER POUR TELECHARGER LE LIVRET

FLAMENCO

1952-1961

TERREMOTO DE JEREZ - AMALDEN

Niña De Los Peines - Carmen Amaya

Manolo Caracol - SABICAS

FLAMENCO 1952-1961

Un peu d’histoire

Il n’est qu’une seule certitude quant aux racines, aux fondations et à l’essence du Flamenco : cette forme musicale issue du petit peuple des campagnes, des montagnes et des quartiers citadins pauvres de Séville, de Jerez de la Frontera ou de Malaga est née de la rencontre de l’orient et de l’occident en terre andalouse, une terre de passage où se sont installés au XVIe siècle des gitans venus de l’Inde au sein d’une population de brassage ibérique et arabe. L’assertion qui veut associer le Flamenco aux seuls gitans n’est donc pas totalement fondée même si elle garde une large part de vérité et, pour expliquer certains aspects comme les mélismes arabisants, des postures de la danse ou quelques inflexions rythmiques, certains ont souhaité souligner des sources historiques indiennes, byzantines ou arabes voire juives. Des intellectuels sincères comme Manuel de Falla et Federico Garcia Lorca, pour estomper une image qui semblait négative en Espagne et lui donner une respectabilité plus andalouse, sont même aller jusqu’à le rebaptiser en 1922 de « Cante Jondo », com-me s’il fallait encore ajouter à la confusion. Quoi qu’il en soit, au final, l’essence du Flamenco, c’est le bras-sage culturel au fil des siècles qui donne naissance à une musique qui ne sombrera jamais dans un folklore en voie d’extinction.

C’est aux ferments de cette histoire de métissage que se nourrissent, plus ou moins consciemment, les « can-taores » (les chanteurs) et « tocaores » (guitaristes) que présente notre anthologie. Certains sont nés à la fin des dernières décades du XIXe siècle et ont croisé et/ou accompagné Don Antonio Chacón, Manuel Torre et portent les règles d’une musique toujours en gestation, d’autres sont nés avec le siècle et les « cafés cantantes ». Au cours des années 1950, la période que couvre notre anthologie, ils sont la mémoire qui ne flanche pas du Flamenco que le franquisme cherche alors à étouffer sous des oripeaux folkloriques. La chance du genre est que dans les quartiers populaires des villes d’Andalousie il s’est perpétué dans les cris de la vie quotidienne et lors des fêtes comme le suggèrent les enregistrements réalisés en 1952 par le musicologue américain Alan Lomax.

Le Concept de Pureté

Dans les dernières décades du XIXe siècle, époque à laquelle le Flamenco pointe à l’horizon comme un genre musical à part entière et non comme une musique dégénérée de gitans déclassés, il est une assertion qui revient en boucle, c’est celle du concept de pureté. Dès que la zone géographique d’influence s’étend, dès qu’une nouvelle génération émerge, dès qu’il se donne à entendre en des lieux nouveaux (café cantante, théâ-tre ou tablao ; en Andalousie mais aussi à Madrid) ou sur des supports technologiques nouveaux (du 78 Tours au CD), il est de bon ton de clamer que le Fla-menco perd de sa pureté. On en fera grief, par exemple, à Camarón de la Isla dans les années soixante-dix, époque à laquelle le Flamenco trouve un nouveau souffle expressif. Et son compère Paco de Lucía de répondre en substance : « le Flamenco a toujours su assi-miler ce qui était assimilable à son esprit et à sa nature et son évolution ne peut que se concevoir de manière imperceptible...Pour moi, tout avance si on sait garder l’équilibre. Je pense qu’il est vital de ne pas perdre de vue la tradition, parce que c’est là que se tiennent l’essence, le message et les fondations. Si vous pouvez construire dans n’importe quelle direction, vous ne pouvez pas perdre les racines parce que c’est là que siège votre identité, le goût et l’odeur du Flamenco »

Une chose est certaine : on n’entre pas par effraction dans ce genre musical impudiquement pudique, aride et hautain. Il impose une écoute attentive, une empathie active, l’oubli de certains critères classiquement admis du beau pour s’en forger d’autres en ayant l’audace de percer ses secrets alchimiques et d’en accepter sa philosophie libertaire. Comment trouver son chemin ? D’aucuns, comme ceux qui aiment le blues ou le samba, s’attacheront en priorité au grain des voix, à l’émotion qui sourde d’un cri quasi primal, d’autres privilégieront la sensibilité rythmique des « tocaores » alors que les kinesthésiques entreront par la porte des danses. Mais on doit admettre qu’une fois les codes percés, on ne sort plus indemne de ce genre musical qui porte haut la noblesse musicale populaire.

Les Rugueux et le Policé

Aux détours des années 1900, le Flamenco - dont le nom apparaîtra seulement au moment de sa profes-sionnalisation - sort du cadre intime et des tavernes gitanes pour entrer dans les « cafés cantantes » dont le plus fameux fut celui de Silvério Franconetti, un italo-andalou. Deux esthétiques vont alors s’affronter : le rugueux gitan face au policé occidental. Le chant, toujours primordial dans le Flamenco, est le lieu idéal pour mesurer l’affrontement des deux antagonismes. Ce sera la voix gitane qui blesse, « que hiere », rauque, rugueuse, cassée, éraillée dite « affila », en référence au chanteur du début du siècle El Fillo, contre la voix « laina », haute et vibrante ou la douce voix « redonda » plus occidentalisées. Il est bien vrai que le chant ne pouvait plus, face à un public, se contenter d’être brut et uniquement accompagné « a palo seco » (tra-duc-tion : un long bâton soit une sorte de canne qui permet de frapper le sol pour marquer le rythme) ou par un marteau sur une enclume ou par des « palmas ». Il lui fallait le soutien d’un instrument et c’est de cette époque que date l’essor de la guitare flamenca dont Ramón Montoya - il n’était d’ailleurs pas gitan - sera le premier virtuose à se produire en soliste. Cette guitare flamenca, plus étroite et plus légère, a ses propres carac-té-ris-tiques dues à la conformation de sa caisse : le son est réfléchi plus vite et induit une dynamique plus violente. Un guitariste Flamenco se reconnaît par la vigueur dans l’attaque, par une sonorité brillante et l’utilisation des syncopes et des silences, par les coups frappés sur la table d’harmonie, l’orientalisme et les couleurs inso-lites des gammes ainsi que par le « rasgueado » avec le pouce. C’est de l’osmose de divers ingrédients que va naître l’équilibre classique caractéristique du Flamenco autour des éléments constitutifs que sont le chant, la guitare flamenca, le « baile » (la danse), les « palmas » (claquement des paumes de la main) et le « zapateado » (coup de talon pour marquer le rythme) sans oublier les « coplas », les couplets dont la poésie de veine populaire séculaire vante un art de vivre. Il n’empêche, c’est le couple voix/ guitare qui sonne le mieux même si tous les « cantes » à voix nue et les « Saetas », avec leur accompagnement de « cornetas » et « tambores », filent le frisson.

Les Palos

Ce sont tous les « cantes » qui sont à la base du Fla-menco et c’est à leurs sujets que les discussions sont les plus vives entre musicologues et mélomanes. C’est aussi ce qui est, sans doute, le plus difficile à appréhender par un non-initié. La classification la plus simple est celle qui s’articule autour des rythmes binaires (rumba, tangos, tientos) et les ternaires, à savoir tous les autres (soléas, bulerias, alegrias, caracoles, fandangos, siguiriyas) Ajoutons que fandangos est le terme générique qui englobe les malagueñas, les granaínas - qui sont des fandangos de Malaga - et les fandangos de Huelva. On peut ajouter que les verdiales et les fandangos de Huelva sont des chants avec « compás » alors que tout les autres sont des chants libres qui, de ce fait, écartent la danse. Il est une jolie formule qui dit que la solea est la mère des rythmes à trois temps et que les tarentos sont la figure paternelle des « compás » à 4 temps.

Les Enregistrements des Années 50

Tout en écartant une approche encyclopédique qui sentirait trop le parfum folklorique, il a bien fallu puiser dans des réalisations d’époque dont l’objectif était de relever tous les cantes afin de valoriser une musique qui n’était alors audible pour le grand public que depuis une trentaine d’années. On ajoutera qu’un cante comme le « martinete » - celui qui fait appel aux coups du marteau sur une enclume - qui peut apparaitre à certains comme trop ancré dans la tradition, est toujours présents dans les concerts de Flamenco.

Les années cinquante furent une époque bénie où les majors du disque prenaient encore des risques pour le bienfait de l’histoire de la musique et de la culture espagnole. On trouvera donc dans notre anthologie un large écho des enregistrements parus respectivement en1954 (Antologia Del Cante Flamenco) et en 1958 (Una Historia Del Cante Flamenco), de Manolo Caracol, réalisations faites sous la houlette de musicologues patentés alors que le franquisme, lui, valorise l’Opéra Flamenco. En cette période où le Flamenco que l’on pourrait qualifier de libertaire vit donc une relative mise en sommeil, Hispavox, sous la houlette du musicologue Tomás Andrade de Silva, monte un projet fantastique autour du guitariste Paco del Valle - connu comme Perico el del Lunar, dans le milieu Flamenco - un guitariste au toucher doux et agile ayant accompagné Don Chacón et dont la probité artistique est reconnu de tous. A ses côtés, on trouve des cantaores anciens, né à la fin du XIXe siècle comme Pepe de la Matrona ou Bernardo el de los Lobitos et des cantaores dans la force de la trentaine et de la quarantaine à l’époque de l’enregistrement comme Rafael Romero ou Roque Montoya (Jarrito). En huit jours et huit nuits, dans un studio madrilène, on essaie de retrouver le climat idéal pour que les artistes donnent le meilleur de l’art du Cante. On ira même jusqu’à enregistrer une fanfare de cornetas y tambores au pas de procession et en plein air afin de reproduire au plus près le son débordant de la saeta. Cette anthologie couvre les Cantes Matrices (les chants de base), les estilos camperos (les chants campagnards), les Cantes autoctonos (chants qui puisent à l’essence du Flamenco sans relever directement du genre, comme la Nana par exemple), les Cantes sin guitarras (chants sans accom-pa-gne-ment de guitare), les Cantes de Levante (les chants de la partie est de l’Andalousie), les estilos de Malaga (les chants de la province de Malaga) ainsi que les Cantes con baile (les chants pour la danse), soit un panorama exemplaire du Flamenco des origines jusqu’aux années cinquante, soit aussi la légitimité, la densité et la vérité du Cante Jondo archéologique et de ses variantes, soit enfin l’expression d’une tradition collective comme interprétation d’un idéal.

Cette anthologie de trois LP, qui se verra décerner le Grand Prix de l’Académie du Disque, paraitra chez Hispavox en 1954, sortira ensuite chez Ducretet-Thomson en 1958 avant d’être rééditée par Hispavox en 1960 pour le marché espagnol.

Quelques années plus tard, Manolo Caracol, à l’apogée de son art, se lance dans un projet ambitieux sous la direction du musicologue Manuel Garcia Marcos. Il y reprend tous les chants de base avec un accompa-gnement somptueux de Melchor de Marchena, son guitariste attitré. En 1966 (donc hors de notre antho-logie pour des raisons légales), le grand chanteur Antonio Mairena, qui fut aussi un musicologue fier de ses racines, fera paraître « La Llave de Oro del Cante Flamenco», enregistrement de qualité qu’on recom-mande chaudement de se procurer. De son côté, entre 1952 et 1958, le musicologue américain Alan Lomax, en virée en Europe, enregistre sous forme de collectage l’expression populaire andalouse. Nous empruntons au volume 3, dévolu à Jerez et Séville, des plages musicales qui donnent une respiration de simplicité quotidienne tout en soulignant la prégnance du Flamenco auprès de populations qui n’ont parfois pas les moyens de s’offrir une guitare.

La Danse

Elle est représentée ici par Carmen Amaya et par les enregistrements pris sur le vif par Alan Lomax. On notera que l’intensité reste la valeur fondamentale du « baile flamenco ». Avant tout individuelle et abstraite dans la mesure où elle ne fait référence à aucun argu-ment narratif, il suffit à la danse flamenca d’un espace réduit, partagé avec un guitariste et, éventuellement un chanteur, pour improviser ses figures. Ne pouvant se marier avec la gravité tragique du Cante Jondo, la danse flamenca ne colle qu’avec les rythmes plus souples et légers qui s’inscrivent dans les catégories dites du Cante Chico (fandangos, sevillanas) ou du Cante Intermedio (bulerias). C’est entre 1920 et 1950, à la période dite de « la opéra flamenca », que le fandango s’impose définitivement en lien avec la profession-nalisation d’artistes comme Carmen Amaya qui se produisent dans des théâtres en quelque chose qui se rapproche plus du ballet classique avec chorégraphie pensée et répétée que du « baile flamenco » traditionnel. Les sevillanas, proches du « baile flamenco » sans en relever vraiment, sont plus extraverties et sont les seules dans le panorama à se danser à deux.

Les Artistes de ce Disque

Nous citons ici les artistes qui se produisent dans cette anthologie mais également quelques figures historiques dont les noms apparaissent dans le corps du texte de présentation.

Perico El Del Lunar (Pedro del Valle)

Né en 1894 et décédé à Madrid en 1964, ce guitariste est une importante figure du flamenco parce qu’il fut l’accompagnateur de Manuel Torre, de Tomás Pavon, de Niña De Los Peines et surtout de Antonio Chacón pendant douze ans. Sa maîtrise et sa connaissance du style traditionnel en font l’interlocuteur idéal des cantaores de l’anthologie réalisée pour Hispavox.

Pepe El De La Matrona (José Nunez Melendez)

Né en 1887 d’une mère sage-femme («matrona » en espagnol) d’où lui vient sur surnom, il est le doyen des sessions d’Hispavox en 1954. Il passe son enfance dans le quartier gitan de Triana à Séville et sera un prota-goniste des « cafés cantantes » en ayant pour mentor Don Chacón. Spécialiste des soléares et grand érudit à l’égal d’Antonio Mairena, il disparaît en 1980.

Rafael Romero

Gitan de Jaen, né en 1910, il devint professionnel malgré l’opposition paternelle. Spécialiste des cantes sans guitare comme les peteneras ou les tientos, il fut un pilier du tablao Zamba. Il chantait les yeux ouverts en tendant la main devant lui, main sur laquelle brillaient trois diamants sur un anneau d’argent. On le surnommait aussi «el gallina ».

Pericon de Cadiz (Juan Martinez Vilches)

Né à Cadix en 1901 et décédé en 1980, il fut marchand de caramels pendant son enfance. Il avait obtenu le 1e prix de soleares à Madrid en 1936 et celui de siguiriyas en 1948.

Bernardo El de Los Lobitos (Bernardo Alvarez Perez)

C’est l’autre « ancien » de l’anthologie Hispavox, puis-qu’il est né en 1887 à Séville. Il avait un style innovant. Son surnom lui vient d’une buléria qu’il avait cout-ume de chanter : « a noche sonaba que los lobitos me comian » (cette nuit, j’ai rêvé que des petits loups me mangeaient). Cet archiviste des styles anciens est mort à Madrid en 1969.

Niño de Almaden (Francisco Antolin Gallego)

Né à Ciudad Real en 1899, il travaillait dans les mines de charbon comme son père. Cet admirateur de Don Chacón, mort en 1968, était un pur représentant des styles du Levant.

Roque Montoya Heredia dit Jarrito

Né à Algésiras (province de Cadix) en 1925 et décédé en 1995, il fut barman du musée tauromachique avant d’être reconnu comme un excellent styliste par Tomás Pavon et sa sœur Niña de Los Peines.

Carmen Amaya

Danseuse, et aussi parfois chanteuse, née à Ciudad Réal en 1913 et décédée à Barcelone en 1963 à l’âge de 48 ans, elle était réputée pour son tempérament anticon-formiste. Elle dirigeait une compagnie dans laquelle Sabicas était le guitariste attitré. Elle se produit dans le monde entier, tourne des films à Hollywood, gagne des fortunes mais, généreuse et prodigue, pris dans les rets de la famille, elle doit se dépenser sans compter en voyages incessants jusqu’à prendre froid dans un train et en mourir d’une infection pulmonaire.

Don Antonio Chacón

Ce natif de Jerez de la Frontera, décédé à Madrid en 1929, est le « cantaor » le plus important de l’histoire du flamenco, le seul à porter le titre de « Don ». Réputé pour les malagueñas et les cantes du Levant qu’il donnait, il eut aussi le mérite de faire passer le genre des cafés cantantes aux théâtres.

El Fillo

Cette figure légendaire est un sévillan né en 1878, disciple de El Nitri et de Silverio. Il avait une voix « afi-lla », c’est à dire rauque. La date de sa mort reste inconnue.

Manolo Caracol (Manuel Ortega Juarez)

Issu d’une grande famille gitane, il est le « cantaor » le plus exceptionnel du XXe siècle. Reconnu dès l’âge de 12 ans pour l’obtention du premier prix au Concours de cante Jondo de Grenade de 1922, l’historique con-cours lancé par Manuel de Falla et Federico Garcia Lorca. Son succès public tient aussi aux spectacles qu’il donne avec Lola Flores, le grand amour de sa vie, des spectacles aux danses flamenquisées ainsi qu’aux quatre films qu’il a tournés (dont trois avec Lola Flores.) Ces dérives n’enlèvent rien à un talent qu’il suffit de peser en l’écoutant dans les volumes 1 et 2 de « Una Historia del Cante Flamenco », accompagné par le génial Melchor de Marchena, son guitariste qui lui restera toujours fidèle tant il était sous le charme de cette voix « afilla ». Mort dans un accident de voiture en 1973, Manolo Caracol a, comme Niña De Los Peines, sa statue à Séville.

Tomás Pavon Cruz

Né en 1893 et mort en 1952, il était le frère de Niña De Los Peines. Il fit peu d’apparition en public tant il était timide et discret mais il reste un des grands créateurs du Cante Puro du XXe siècle.

Niña De Los Peines (Pastora Pavon Cruz)

Sœur du précédent et épouse de Pepe Pinto, elle est considérée comme la plus grande « cantaora » de tous les temps pour les styles de fête et elle est sublime dans les peteneras et les tangos. Elle possédait un sens prodigieux du rythme et savait aussi émouvoir. Elle était née à Séville, dans le quartier de Triana, le 10 février 1890 et s’est éteinte le 26 novembre 1969. Issue d’une famille gitane pauvre, analphabète, elle se produit en public à l’âge de neuf ans à la Taberna de Caferino de Séville et son surnom lui vient des vers d’un tango qu’elle chantait. Ses premiers vrais pas professionnels remontent à 1920, année où elle commence à enre-gistrer (cf l’anthologie Ramon Montoya parue chez Frémeaux). Influencée par Arturo Pavon, un frère plus âgé de quelques années et cornaquée par Tomás, l’autre frère, elle fut l’amie de Federico Garcia Lorca à qui elle rendra un hommage lors d’un concert donné à Madrid, la capitale encore républicaine, le 19 août 1937, trois semaines après que le poète ait été fusillé par les troupes de Franco. Lorca disait à son propos : « ce timbre de pur métal ».

Niño Ricardo (Manuel Sanchez)

« Tocaor » de renom né à Séville en 1904 et décédé en 1974, il aura été influencé par Ramon Montoya. Comme lui, il saura harmoniser les caractéristiques de la guitare flamenca et celles de la guitare classique et se produira en soliste.

Sabicas (Agustin Castellon Campos)

Autre tocaor incontournable du Flamenco. Né à Pampelune en 1912, neveu de Ramon Montoya, il résidera longtemps au Mexique et aux Etats Unis, ce qui explique son décès à New York en 1990. Il avait fait partie de la compagnie de Carmen Amaya, signé de nombreuses compositions et ouvert de nouveaux hori-zons pour la guitare flamenca dont saura se saisir la nouvelle génération éclose dans les années soixante.

Ramon Montoya

Né en 1879 à Madrid et décédé en 1948 toujours à Madrid, il fut un guitariste autodidacte qui fit ses classes auprès de Don Chacón et qui a aussi accompagné La Niña de Los Peines. Il avait développé un jeu de falsetas inattendues et se produisait aussi en récital. Son nom reste gravé dans les mémoires comme le guitariste le plus célèbre de l’histoire du Flamenco (cf « l’art de Ramon Montoya » FA 5049, éditions Frémeaux).

Manuel Morao (Juan Moreno Jimenez)

Tocaor natif de Jerez de la Frontera, il est le beau-frère de Terremoto et le père de Moraíto. Outre ses qualités de musicien, il est admiré pour avoir soutenu de jeunes artistes.

Terremoto (Fernando Fernandez Monje)

Le chant à l’état brut, celui qui vient des tripes et qui dit ce que la parole ne sait pas exprimer. C’est que Terremoto était un analphabète total, ne sachant ni lire ni écrire. On raconte qu’à l’enterrement de sa mère adorée, il rompit un mutisme atroce en se lançant dans un chant à gorge déployée Por siguiriyas. Gitan de Jerez, il se destinait à la danse avant de rejoindre un tablao de Séville. Chanteur très irrégulier, il fonctionnait avant tout à l’inspiration. Son beau frère Manuel Morao disait : « Yo creo que era todo intuitivo. Lo tenia todo dentro, lo tenia en la sangre, lo tenia en el alma, lo tenia en el corazon. Era un hombre que no sirvio mas que para cantar » (Je crois que tout était instinctif. Il le portait à l’intérieur de lui, il l’avait dans le sang, il l’avait dans l’âme, il le portait dans son cœur. C’était un homme qui ne savait rien faire d’autre que chanter). Né le 17 mars 1930, il a enregistré un premier EP en 1956 avant de retrouver les chemins des studios en 1963.

Fosforito (Antonio Fernandez Diaz)

Né le 3 août 1932 à Cordoue. Il est le cinquième garçon d’une famille humble de huit enfants. Un de ses oncles avait été un chanteur reconnu. En 1956, au Concours de Cordoue, à l’âge de 23 ans, alors qu’il relevait d’une grave opération intestinale qui l’avait écarté du chant pour se consacrer à la guitare, il remporte le premier prix de chaque catégorie de cante, ce qui est un fait unique dans l’histoire du Flamenco. En 1999, il a enre-gistré un magnifique disque où il est accompagné par Paco de Lucía.

Philippe LESAGE

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

Remerciements au photographe René Robert pour le prêt du disque réalisé par Alan Lomax et à Alexis Frankel qui est aussi un guitariste flamenco et qui m’a donné de précieux conseils.

Glossaire

Pour assimiler et retenir quelques mots qui reviennent sans cesse.

Bailaor : Danseur de Flamenco

Cantaor : Chanteur de Flamenco

Tocaor : Guitariste Flamenco

Palmero : le musicien qui assure les « palmas » (frapper dans les paumes des mains). « Car un bon palmero vous rehausse le plat, il aide la chanteur à sortir ce qui doit, le remet dans le droit chemin, s’efface devant ses silences » (David Fauquemberg dans « Manuel El Negro »)

Cante : Mot réservé au Flamenco car, en espagnol, pour tout chant non Flamenco, on utilise le terme « canto ». Comme l’écrit David Fauquemberg dans son roman « Manuel el Negro » : « De l’alegria au tarento, il y a un monde. Chacun des « palos » exprime une émotion dis-tincte. Otez-la, il ne reste rien ». De son côté, le grand chanteur Antonio Mairena, qui eut aussi une action de musicologue, disait : « Nous sommes convaincus de l’im-possible définition du cante. Son ins-piration n’est pas esthétique, il ne recherche pas, non plus, la facilité et son but n’est pas d’amuser. »

Cante Jondo : Chant profond ; la force d’expression nait des sentiments les plus intimes. Le terme s’applique aux cantes ayant des résonnances anciennes. Luiz Lopez Ruiz, dans son livre « Guide du Fla-menco » précise : « Le cante est l’art des opprimés et des minorités. Dans le cante Jondo, l’expression dérive uniquement d’une passion personnelle. »

Compás : Mesure d’une phrase musicale qui tient compte du rythme et de la guitare

Duende : « Le duende est un pouvoir et non un acte. Une lutte, non une pensée. » (Gar-cia Lorca) C’est être dans un état d’ins-piration proche de la transe.

Falsetas : Solos de la guitare flamenca

Jaleo : Manifestations diverses pour encou-rager les interprètes.

Palo : Type de cante .

Voix affila : Voix rauque, sans doute idéale pour chanter le Flamenco. Elle est bien représentée dans notre anthologie par Manolo Caracol et Terremoto.

Bibliographie

Luis Lopez Ruiz : « Guide du Flamenco » (L’Harmattan éditeur)

Bernard Leblon : Flamenco (Cité de la Musique -Actes Sud)

Clément Lépidis : L’or du Guadalquivir (roman ; Editions du Seuil)

Francis Marmande : Rocío (Verdier)

David Fauquemberg : Manuel El Negro (roman, fayard)

FLAMENCO 1952-1961

History

Concerning the roots, foundations and essence of Flamenco, only one thing is certain: this musical form practised by those who lived in the poor quarters of Seville, Jerez de la Frontera or Malaga, and the surrounding countryside and mountains, was born out of the encounter between Orient and Occident in the land of Andalusia, where, in the 16th century, gypsies arriving from India settled amidst Iberian and Arab peoples. So the assertion that flamenco belongs to gypsies alone is not entirely founded, even though largely true; and to explain certain aspects of flamenco — Arabic melismata, the poses and gestures of its dances, certain rhythmical inflexions — others have underlined historic sources: Indian, Byzantine or Arabian, even Jewish. In 1922, intellectuals like Manuel de Falla and Federico Garcia Lorca quite sincerely sought to soften its seemingly negative image in Spain, and give the genre a more Andalusian respectability: they even went so far as to rechristen the genre Cante Jondo, as if there were not enough confusion already. But when all is said and done, the essence of flamenco is that cultural mix which, over the centuries, gave birth to music that has never foundered; it is no folklore destined for extinction.

The fermentation in this history of cultural mixing is that which nourished, more or less consciously, the cantaores (singers) and tocaores (guitarists) to whom our anthology is devoted. Some were born in the last decades of the 19th century, and their paths crossed those of Don Antonio Chacón and Manuel Torre; indeed they played with them, according to the rules of music that was still in gestation. Others were born with the 20th century and its cafés cantantes. In the course of the Fifties, the period covered by this set, they represent the unfailing memory of flamenco which Francoism was then attempting to stifle with the flashy rags of traditional songs. In the popular city-quarters of Andalusia, the genre was fortunate enough to be perpetuated in the shouts and cries of everyday life, and in feasts and festivals like those suggested by the 1952 recordings made by American musicologist Alan Lomax.

The Concept of Purity

In the last decades of the 19th century — the dawn of flamenco as a music genre in its own right, and not some “degenerate” music form spread by second-class gypsies — one notion which constantly returned was the concept of purity. As soon as its influence spread beyond Andalusia, or when a new generation emerged, or as soon as it was heard in a new venue — a café cantante, theatre or tablao whether in the south or in Madrid — or by some new technical means, from a 78rpm record to a CD, flamenco was commonly said to be losing its purity. In the Seventies, for example, when flamenco expressions found new breath, Camarón de la Isla was rebuked for that loss; his musical partner Paco de Lucía would reply to such reproaches by saying in substance, “Flamenco has always assimilated everything that was to be absorbed in spirit and nature, and its evolution can only be conceived in an imperceptible manner… In my view, everything advances if a balance can be maintained. I think it is vital not to lose sight of the tradition, because that is where the essence, the message and the foundations are to be found. If you are able to build, whatever the direction, then you cannot lose those roots, because that is where your identity, the taste, and the smell, of flamenco lie.”

One thing is certain: this shamelessly modest, arid and high-mannered music genre cannot be entered by just breaking down a door. It demands careful listening, an active empathy, and it also requires you to forget certain classically-acknowledged criteria of beauty so that you may forge others in daring to pierce the secrets of its alchemy, and in accepting its libertarian philosophy. How does one find one’s way into all this? Some, such as those who love blues or sambas, will at first concentrate on the grain of flamenco voices, on the emotion which wells up from inside an almost primal cry; there are those who will favour the rhythmical sensibilities of the tocaores, while others will kinaesthetically enter through the doors of flamenco dan-cing. But once inside, with the codes deciphered, it must be admitted that one can no longer come out of this music genre unscathed: it is a genre which holds high the popular nobility of music.

The Rough and the Civilized

In the course of the 1900s, flamenco — the term would only appear with the advent of professionalism — came out of its intimate setting and gypsy taverns to enter the cafés cantantes, and the most famous of these was owned by Silvério Franconetti, an Italo-Andalusian. Two aesthetics would face each other: those of the rough gypsy and the civilized westerner. Song, always primordial in flamenco, was the ideal ground to measure the confrontation between the two antagonisms: it would be the gypsy voice that hurts, “que hiere”, raucous, rough, broken and hoarse — the voice was called afilla, in reference to the singer El Fillo who was popular at the turn of the century — versus the voice called laina, high and vibrant, or the softer redonda voice that belonged more to the West. It is quite true that, when faced with an audience, a song could no longer content itself to be raw and accompanied solely by a palo seco (i.e. with a long stick or cane which would strike the floor to beat the rhythm), or a hammer and anvil, or palmas (handclaps). Songs needed the backing of an instrument, and so began the rapid rise of the guitarra flamenca, whose first virtuoso soloist was Ramón Montoya, incidentally not a gypsy. This flamenco guitar, narrower and lighter, had its own characteristics due to the shape of its body: the sound was reflected more quickly and resulted in more violent dynamics. A flamenco guitarist was recognizable: a vigorous attack, a brilliant sound, the use of syncopation and rests, the slaps given to the soundboard, and oriental traits such as the unusual colouring of the scale or the rasgueado effect produced by the thumb. The osmosis of various ingredients gave birth to the classical balance characteristic of flamenco, whose elements are song, the flamenco guitar, baile, or dancing, palmas (slapping the palms of the hands together) and the zapateado (stamping with one’s heel to mark the rhythm), not forgetting the coplas or couplets whose poetry — in a secular, popular vein — vaunted a way of life. All the same, it was the voice/guitar pairing which sounded the best, even if the cantes sung by a voice alone, and the Saetas with their accompanying cornetas and tambores, could make listeners shiver.

The Palos

Those cantes lie at the foundations of flamenco, and also at the heart of the liveliest discussions between musicologists and music-lovers. They are also the part of flamenco which is most difficult to apprehend for a non-initiate. The most simple classification is that which separates binary rhythms (rumba, tangos, tientos) from ternary rhythms, in other words, all the others (soleás, bulerias, alegrias, caracoles, fandangos, siguiriyas). It should be noted that fandan-gos is a generic term which embraces the malagueñas, the granaínas — the fandangos of Malaga — and the fandangos of Huelva. Concerning the latter, the verdiales and fandangos of Huelva are songs with compás whereas the others are all free songs, which rules out dancing. There’s a rather nice formula which says that the soleá is the mother of rhythms in three, and that tarentos are the father figure of those compás (measures) in four.

Fifties recordings

An encyclopaedic approach to this set had to be avoided — it would have given the contents an excessive “folk-music” flavour — but it was still necessary to draw on recordings of the period, the aim being to select all the cantes which provide the value of a style of music which hadn’t been heard by most audiences until thirty years ago. It might be added that a cante or martinete — the one with recourse to a hammer striking an anvil —, which might appear too anchored in tradition for some listeners, were always present in flamenco concerts.

The Fifties were years that were blessed, in that major record companies would still take risks for the sake of music history and Spanish culture. So our anthology contains a large echo of recordings by Manolo Caracol which appeared respectively in 1954 (“Antologia Del Cante Flamenco”) and in 1958 (“Una Historia Del Cante Flamenco”), productions made under the aegis of officially recognized musicologists, while Francoism preferred Opera Flamenco. So in this period, which saw the kind of flamenco one might call libertarian made relatively dormant, Hispavox, led by the musicologist Tomás Andrade de Silva, undertook a fantastic project devoted to guitarist Paco del Valle — known in flamenco circles as Perico El Del Lunar —, a guitarist with a soft, nimble touch who had accompanied Don Chacón and whose artistic integrity was recognized by all. Alongside him you can find older-generation cantaores born at the end of the 19th century, like Pepe de la Matrona or Bernardo el de los Lobitos, and cantaores who were in their vigorous thirties and forties at the time they were recording, like Rafael Romero, or Roque Montoya, known as Jarrito. For eight days and nights in a Madrid studio, they tried to recreate the ideal atmosphere for the artists to give the best of their art of the Cante. Even a marching band of cornetas y tambores was re-created outdoors so that they could come closest to the sound spilling out of the saeta. This anthology covers the Cantes Matrices (the basic songs), the estilos camperos or songs of the countryside, the Cantes autoctonos (songs drawing from the essence of Flamenco without directly being part of the genre, like Nana for example), the Cantes sin guitarras (songs without a guitar accompaniment), the Cantes de Levante (from eastern Andalusia), the estilos de Malaga (songs from the Malaga province) and also the Cantes con baile (songs for dancing); in other words, a complete panorama of flamenco from its origins to the Fifties, and therefore also a panorama of all the legitimacy, density and truth of the archaeological Cante Jondo and its variants: this, finally, represents the expression of a collective tradition as the interpretation of an ideal.

The resulting anthology of three LPs, which was awarded the “Grand Prix de l’Académie du Disque” in France, was issued by Hispavox in 1954, released by Ducretet-Thomson four years later in 1958, and then reissued by Hispavox in 1960 for the Spanish market.

A few years later, Manolo Caracol, now at the apogee of his art, undertook an ambitious project for which the musicologist Manuel Garcia Marcos was responsible. For this project he went back to all the basic songs, but this time he was sumptuously accompanied by Melchor de Marchena, his regular guitarist. In 1966 — legal reasons prevent its inclusion here — the great singer Antonio Mairena, who was also a musicologist, and a man who took pride in his roots, published “La Llave de Oro del Cante Flamenco”, a recording of great quality which we heartily recommend. As for American musicologist Alan Lomax, between 1952 and 1958 he travelled in Europe gathering field-recordings of popular expressions in Andalusia. From the third volume of his collected recordings, which was devoted to Jerez and Seville, we have borrowed tracks where the music breathes with the simplicity of everyday life in demonstrating the vivid resonance of flamenco in a population often without the means to own guitars of their own.

Dancing

Dancing is represented here by Carmen Amaya and field-recordings made by Alan Lomax. Note that intensity remains the fundamental value of the baile flamenco. It is above all individual and abstract, insofar as it does not refer to any narrative argument; a reduced space shared with a guitarist and, if need be, a singer, is enough for the flamenco dancer to improvise the appropriate figures. Unable to espouse the tragic gravity of the Cante Jondo, the flamenco dance only suits the lighter, more flexible rhythms which belong to the so-called Cante Chico categories (fandangos, sevillanas) or those of the Cante Intermedio (bulerias). It was in the opera flamenca period, from 1920 to 1950 that the fandango established itself definitively, an era when artists like Carmen Amaya turned professional and began appearing in theatres: their performances were closer to classical ballet, with planned and rehearsed choreographies, than to the traditional baile flamenco. The sevillanas, close to baile flamenco although not directly related, were the only dances performed by pairs.

The Artists

The following is a list of the artists included in this anthology; also listed are some historical figures whose names appear in the introduction.

Perico El Del Lunar (Pedro del Valle)

Born in 1894 (d. Madrid 1964), this guitarist was an important flamenco figure because he accompanied Manuel Torre, Tomás Pavon, La Niña De Los Peines, and especially Antonio Chacón, whom he partnered for twelve years. His mastery and knowledge of the traditional style made him the ideal accompanist for the cantaores appearing in the Hispavox anthology.

Pepe El De La Matrona (José Nunez Melendez)

Born in 1887 (his mother was a midwife or matrona, hence his nickname), Melendez was the most elderly performer on the 1954 Hispavox sessions. He spent his infancy in the gypsy quarter of Triana in Seville, and was a notable figure in the cafés cantantes (his mentor was Don Chacón). A soléares specialist and as learned a musician as Antonio Mairena, he passed away in 1980.

Rafael Romero

A gypsy born in Jaen in 1910, he turned professional against his father’s wishes. As a specialist of cantes sung without a guitar, like the peteneras or the tientos, he was an unavoidable figure at the Zamba tablao. He sang with his eyes open, holding out a hand where three diamonds sparkled from the silver ring worn on his finger. He was also known by the name El gallina.

Pericon de Cadiz (Juan Martinez Vilches)

Born in Cadiz in 1901 (he died in 1980), he sold toffees as a child. In 1936 in Madrid he won First Prize for his soleares, and in 1948 he was awarded the prize again, this time for his siguiriyas.

Bernardo El De Los Lobitos (Bernardo Alvarez Perez)

Alvarez Perez was the other “elder” featured in the Hispavox anthology; he was born in 1887 in Seville. He had an innovative style and owed his nickname to a buleria he used to sing, “Last night I dreamed that little wolves were eating me.” [“A noche sonaba que los lobitos me comian”.] This archivist of old styles died in Madrid in 1969.

Niño de Almaden (Francisco Antolin Gallego)

Born in Ciudad Real in 1899, he worked in the coalmines like his father. A great admirer of Don Chacón, he was a pure representative of the Levant styles. He died in 1968.

Roque Montoya Heredia (known as “Jarrito”)

Born in 1925 in Algeciras in the province of Cadiz (he died in 1995), “Jarrito” was a barman at the bullfighting museum before Tomás Pavon and his sister La Niña de Los Peines recognized him as an excellent stylist.

Carmen Amaya

A dancer (and sometimes a singer), Carmen Amaya was born in Ciudad Réal in 1913 and died young at 48 in Bar-celona (1963). She was renowned for her non-conformist temperament, and directed a dance-company whose usual guitarist was Sabicas. Amaya appeared all over the world, making films in Hollywood and amassing a fortune. She was generous to a fault and, ensnared by the family, she dilapidated her wealth travelling constantly… she would catch cold in a train and die of a pulmonary infection.

Don Antonio Chacón

This native of Jerez de la Frontera who died in Madrid in 1929 was the most important cantaor in flamenco history, the only singer to carry the title of “Don”. Renowned for his malagueñas and the cantes of the Levante province which he performed, he also had the merit of transferring the genre from the cafés cantantes to theatres.

El Fillo

This legendary figure was born in Seville in 1878, a disciple of El Nitri and Silverio. He had a hoarse voice (the Spanish word is afilla, meaning raucous or rough). The date of his death is unknown.

Manolo Caracol (Manuel Ortega Juarez)

He came from a great gypsy family and became the most exceptional cantaor of the 20th century. He was merely twelve when he won First Prize in Granada in 1922 at the historic Cante Jondo competition set up by Manuel de Falla and Federico Garcia Lorca. His fame with the public was something he owed to the spectacular concerts — featuring flamenco dancers — which he gave with Lola Flores, the great love of his life, and to the four films he made (three of them with Flores). These asides detract nothing from his talents, as you can judge from Volumes 1 & 2 of “Una Historia del Cante Flamenco”, accompanied by the guitar-genius Melchor de Marchena, who remained loyal to him all his life, so much was he taken by the rough charm of Caracol’s voice. After Manolo died in a car-accident in 1973, a statue was raised in Seville, an honour he shared with La Niña De Los Peines.

Tomás Pavon Cruz

The brother of La Niña De Los Peines, he was born in 1893 and died in 1952. He was a shy, retiring figure and so he made few public appearances; but he remained one of the great Cante Puro creators of the 20th century.

La Niña De Los Peines (Pastora Pavon Cruz)

Pastora Pavon, the sister of Tomás Pavon Cruz and the wife of Pepe Pinto, is considered the greatest cantaora of all time, practising all styles to perfection; she was a sublime singer of peteneras and tangos especially. Her sense of rhythm was prodigious, and she was an extraordinarily moving singer. Born in the Triana quarter of Seville on February 10th 1890, she died aged 78 on November 26th 1969. She came from poor gypsy family and could neither read nor write; she began singing in public at the age of nine, at the Taberna de Caferino in Seville, and her nickname was taken from a verse in a tango she used to sing. Her first real steps as a professional came in 1920, the year she began recording (c.f. the Ramon Montoya anthology issued by Frémeaux.) Influenced by her other brother Arturo Pavon, her elder by a few years, she was introduced to the world of flamenco by Tomás and became a friend of Federico Garcia Lorca, to whom she paid tribute at a concert held in Madrid on August 19th 1937 — Madrid was still a Republican capital at the time —, three weeks after the poet was put before a firing squad of Franco’s troops. Lorca said that she had “a timbre of pure metal.”

Niño Ricardo (Manuel Sanchez)

A renowned tocaor born in Seville in 1904 (he died in 1974), he was said to have been influenced by Ramon Montoya. Like the latter, Niño Ricardo succeeded in harmonizing the characteristics of flamenco guitar with those of the classical guitar, and he appeared as a soloist.

Sabicas (Agustin Castellon Campos)

Another peerless flamenco tocaor, Sabicas was born in Pamplona in 1912, and he was Ramon Montoya’s nephew. He lived for a long time in Mexico and The United States, and died in New York in 1990. He belonged to Carmen Amaya’s dance-company, writing numerous compositions and also opening new horizons for the flamenco guitar and the new generation which sprang up in the Sixties.

Ramon Montoya

Born in 1879 in Madrid (where he died in 1948), Montoya was self-taught; he pursued his apprenticeship alongside Don Chacón and also accompanied La Niña de Los Peines, having developed his playing to include unexpected falsetas. He also gave recitals. His name is engraved in the collective memory as the most famous guitarist in the history of flamenco (c.f. “L’art de Ramon Montoya”, Frémeaux FA 5049.)

Manuel Morao (Juan Moreno Jimenez)

A native of Jerez de la Frontera, the tocaor Manuel Morao was the brother-in-law of Terremoto and the father of Moraíto. Apart from his gifts as a musician, he was also admired for the support he gave to young artists.

Terremoto (Fernando Fernandez Monje)

Terremoto was the art of song in the raw state, the kind of song that contains one’s heart and soul and which says everything that cannot be put into words… And Terremoto could neither read nor write. It’s said that at his mother’s funeral — he worshipped her — he broke his dreadful silence and burst into a full-voiced Por siguiriyas. A Jerez gypsy, he was determined to become a dancer before he joined a tablao in Seville. He was a very irregular singer, relying above all on the inspiration of the moment. His brother-in-law Manuel Morao would say that, “I believe it was all instinctive. He carried it inside him; he had it in his blood, he had it in his soul, and he bore it inside his heart. He was a man who didn’t know how to do anything except dance.” [«Yo creo que era todo intuitivo. Lo tenia todo dentro, lo tenia en la sangre, lo tenia en el alma, lo tenia en el corazon. Era un hombre que no sirvio mas que para cantar.»] Born on March 17th 1930 he recorded a first EP in 1956 but didn’t return to a studio until 1963.

Fosforito (Antonio Fernandez Diaz)

Born in Cordoba on August 3rd 1932, he was the fifth male in a humble family of eight children. One of his uncles was a renowned singer. In 1956, at the age of 23, while still convalescing after surgery — a serious stomach operation which had forced him to stop singing and take up the guitar — he was awarded First Prize in each Cante category in competition at Cordoba, a unique achievement in flamenco history. In 1999 he made a magnificent record accompanied by Paco de Lucía.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French text of Philippe Lesage

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

Thanks to photographer René Robert for the loan of the record made by Alan Lomax, and to Alexis Frankel who is also a flamenco guitarist and whose advice was precious.

Glossary

A few terms which constantly appear in references to flamenco are:

Bailaor: a male flamenco dancer

Cantaor: a male flamenco singer

Tocaor: a male flamenco guitarist

Palmero: a musician providing rhythm by clapping his palms together. According to David Fauquemberg in “Manuel El Negro”, “A good palmero enhances the dish; he helps the singer to bring out what he must, puts him back on track, and steps back when he falls silent.”

Cante: a word reserved for flamenco as, in Spanish, the term canto is used for all songs that are not flamenco. To quote David Fauquemberg again in his novel “Manuel El Negro”: “A whole world separates the alegria from the tarento. Each ‘palo’ expresses a distinct emotion. Take it away, and nothing remains.” The great singer Antonio Mairena, who was also a musicologist, said that, “We are convinced that defining the cante is impossible. Its inspiration is not aesthetic, nor does it seek facility; and its aim is not to amuse.”

Cante Jondo: deep song; force of expression born of the most intimate of emotions. The term is applied to cantes with ancient resonances. Luiz Lopez Ruiz, in his book entitled “Guide du Flamenco”, points out that, “The Cante is the art of the oppressed and minorities. In the ‘Cante Jondo,’ the expression derives solely from a passion that is personal.”

Compás: a measure of one musical phrase which takes account of the rhythm and the guitar.

Duende: “Duende is a power and not an act. It is a struggle, not a thought.” (Garcia Lorca). It is an inspirational state close to trance.

Falsetas: flamenco guitar solos.

Jaleo: various manifestations of encouragement given to performers.

Palo: a type of cante .

Afilla: a hoarse-sounding voice, no doubt the ideal voice for a flamenco singer. It is well-represented here by Manolo Caracol and Terremoto.

Bibliography

Luis Lopez Ruiz: “Guide du Flamenco”, (L’Harmattan)

Bernard Leblon: “Flamenco” (Cité de la Musique -Actes Sud)

Clément Lépidis: “L’or du Guadalquivir” (novel, Editions du Seuil)

Francis Marmande: “Rocío” (Verdier)

David Fauquemberg: “Manuel El Negro” (novel, Fayard)

CD1

1 - MEDIAS GRANAINAS Y GRANAINAS (Popular)

Niño de Almaden ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Antologia del Cante Flamenco / Hispavox, 1954

2 - A MI MARE ABANDONE

(E. Duran « El Gitano Poeta ») (Tangos y Tientos)

Niña de los Peines ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

La Voz de su Amo : 7 EPL 13 314 ; 1950 avec réédition en 1959

3 - MI PUEDEN MANDAR (Popular) (La Cana)

Manolo Caracol, guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH – 10-23 ; 1958

4 - EL RENIEGO (Popular) (Siguiriyas)

Manolo Caracol ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH – 10-23 ; 1958

5 - SOY PIEDRA Y PERDI MI CENTRO

(E. Duran « el Gitano Poeta ») (Soleares de la Serneta)

Niña de los Peines ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

La Voz de su Amo : 7 EPL 13 314 ; 1950 avec réédition en 1959

6 - SIEMPRE ESTOY SOÑANDO ( Monge) (Siguiriyas)

Terremoto de Jerez ; guitare : Manoel Moreno (aka Manuel Morao)

Philips EP 421 213, 1956

7 - SOLEARES (Castillo)

Sabicas : guitare solo

LP Fiesta Flamenca, RCA A 130 234, 1961

8 - MALAGUEÑA (Popular)

Collectage à Séville par Alan Lomax

Westminster W – 9804, 1952/ 1958

9 - EN EL CALABOZO (Popular) (Martinetes)

Manolo Caracol ; Guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH – 10-23 ; 1958

10 - TOITA AGUA DEL MAR

(Antonio Fernandez) (Alegrias)

Fosforito, guitare : Vargas Araceli

EP Philips 421 204 ; 1957

11- BULERIAS (Popular)

Juana Morales et Carbonero and friends

Collectage à Séville par Alan Lomax

Westminster W – 9804, 1952/ 1958

12 - NO QUIERO NA CONTIGO (Popular) (Bulerias)

Manolo Caracol ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Una Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH – 10-24 ; 1958

13 - RECUERDO A CARMEN AMAYA

(Castillo) (Garrotín)

Sabicas : guitare solo

Discos Pizarra ; 1958

14 - GARROTÍN (Amaya – Sabicas)

Carmen Amaya et sa compagnie

Enregistré par Decca à New York

Polydor 20976 EP – 1958

15 - FANDANGO DE HUELVA (Popular)

R. Montoya aka Jarrito, guitare : Perico el del lunar

Antologia del Cante Flamenco / Hispavox,1954

16 - ANTES DE LLEGAR A TU PUERTA

(Popular) (Fandangos de Huelva)

Manolo Caracol, guitare : Mel-chor de Marchena

Una historia del cante popular, Hispavox HH – 10-23, 1958

17 - QUE DEL NIO LA COGI (Popular) (Fandangos)

Manolo Caracol, guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH – 10-23 ; 1958I

18 - CUANDO TE VAYAS CONMIGO

(Popular) (Alegrias)

Manolo Caracol ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Una historia del cante popular, Hispavox HH – 10-23, 1958

19 - TONAS (Popular)

Rafael Romero ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Antologia del Cante Flamenco / Hispavox, 1954

20 - MARTINETES (Popular)

Rafael Romero ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Antologia del Cante Flamenco / Hispavox, 1954

CD2

1 - GYPSY DANCE (Popular) (Sevillanas)

Pastora Amaya and Friends

Westminster W – 9804 ; 1952/ 1958

2 - BULERIAS (Popular)

Roque Montoya aka Jarrito ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

3 - EN LA PUERTA CON TU MADRE (Monje) (Bulerias)

Terremoto de Jerez ; guitare : Manoel Moreno aka Manuel Morao

Philips 421 213 EP ; 1956

4 - SE LA LLEVO DIOS

(Popular) (Malagueñas de En-ri-que El Mellizo)

Manolo Caracol ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Una Historia Del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH 10 – 24 ; 1958

5 - MALAGUEÑAS (Popular) Niño de Almaden

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

6 - AL CIELO QUE ES MI MORADA

(Callejon, Torres y Molina Moles) (Fandangos de Huelva)

Niña de los peines ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

La Voz de Su Amo – 7 EPL 13.314 – 1950 ; « recons-truccion1959 »

7 - A QUE NEGAR EL DELIRIO

(Montes Y Torres) (Malagueña)

Niña de los peines ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

La Voz de Su Amo – 7 EPL 13.314 – 1950 ; « recons-truccion1959 »

8 - GITANERIA ARABESCA (Ricardo) (Granainas)

Niño Ricardo : guitare solo

Le Chant du Monde, 1955

9 - SAETAS (Popular)

Roque Montoya aka Jarrito (2 et 4) et Lolita Triana (1 et 3) y Banda de cornetas y tambores

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

10 - RIPE GRAPES (Popular) (Street cries)

Collectage d’Alan Lomax à Seville

Westminster W – 9804 ; 1952/1954

11- DEBAJITO DEL PUENTE (Popular) (Tientos)

Manolo Caracol ; guitare : Melchor de Marchena

Una Historia del Cante Flamenco

Hispavox HH 10 – 24 ; 1958

12 - TIENTOS (Popular)

Niño de Almaden ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

13 - VERDIALES (Popular)

Bernardo el de los Lobitos ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

14 - SEVILLANAS CORREALES (Popular)

Bernardo el de los Lobitos ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

15 - ALEGRIAS (Popular)

Pericon de Cadiz ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

16 - SOLEARES (Popular)

Pepe el de la Matrona ; guitare :Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

17 - CANTES DE TRILLA (Popular)

Bernardo el de los Lobitos ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

18 - PETENERAS (Popular)

Rafael Romero ; guitare : Perico el de lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954

19 - NANAS (Popular)

Bernardo el de los Lobitos ; guitare : Perico el del lunar

Hispavox 40 3011 3 ; 1954I

20 - GYPSY LULLABYE (Popular)

Pastora Amaya

Collectage à Séville par Alan Lomax

Westminster W 9804 ; 1952/1958

Musique populaire au sens noble du terme, le flamenco est issu du brassage culturel de l’Andalousie. Cette anthologie démontre qu’il est bien l’expression d’une tradition collective dont l’idéal a été sublimé par des chanteurs comme Manolo Caracol, Terremoto de Jerez ou Niña de los Peines et des guitaristes comme Melchor de Marchena ou Sabicas. L’Espagne, dans toute sa richesse arabo-judéo-chrétienne et gitane, affirme ici son statut de précurseur dans la world music. Philippe Lesage

As “popular music” in the noble sense, flamenco was born out of the cultural mix which developed in Andalusia. This anthology shows that flamenco is indeed the expression of a collective tradition whose ideal was sublimated by such singers as Manolo Caracol, Terremoto de Jerez or Niña de Los Peines, and guitarists like Melchor de Marchena or Sabicas. Here, the full musical richness of Spain — Arab, Judaeo-Christian and gypsy — affirms its status as a World Music precursor. Philippe LESAGE

CD 1

1. MEDIAS GRANAINAS Y GRANAINAS (Niño de Almaden) 4’13

2. A MI MARE ABANDONE (Niña de los Peines) 2’56

3. ME PUEDEM MANDAR (Manolo Caracol) 4’37

4. EL RENIEGO (Manolo Caracol) 5’03

5. SOY PIEDRA Y PERDI MI CENTRO (Niña de los Peines) 2’45

6. SIEMPRE ESTOY SOÑANDO (Terremoto de Jerez) 6’30

7. SOLEARES (Sabicas) 3’05

8. MALAGUEÑA (Sévillans inconnus) 3’30

9. EN EL CALABOZO (Manolo Caracol) 1’44

10. TOITA AGUA DEL MAR (Fosforito) 3’28

11. BULERIAS (Juana Morales) 3’04

12. NO QUIERO NA CONTIGO (Manolo Caracol) 3’47

13. RECUERDO A CARMEN AMAYA (Sabicas) 3’01

14. GARROTIN (Carmen Amaya) 5’26

15. FANDANGOS DE HUELVA (Roque Montoya / Jarrito) 2’50

16. ANTES DE LLEGAR A TU PUERTA (Manolo Caracol) 2’23

17. QUE DEL NIO LA COGI (Manolo Caracol) 4’15

18. CUANDO DE VAYAS CONMIGO (Manolo Caracol) 2’20

19. TONÁS (Rafael Romero) 1’29

20. MARTINETES (Rafael Romero) 2’53

CD2

1. GYPSY DANCE (Pastora Amaya and friends) 3’15

2. BULERIAS (Roque Montoya / Jarrito) 2’21

3. EN LA PUERTA CON TU MADRE (Terremoto de Jerez) 2’57

4. SE LA LLEVO DIOS (Manolo Caracol) 3’56

5. MALAGUEÑAS (Niño de Almaden) 5’37

6. AL CIELO QUE ES MI MORADA (Niña de los Peines) 2’49

7. A QUE NEGAR EL DELIRIO (Niña de los Peines) 2’52

8. GITANERIA ARABESCA (Niño Ricardo) 3’02

9. SAETAS (Lolita Triana et Roque Montoya / Jarrito) 9’02

10. RIPE GRAPES (Street Cries of Seville) 1’03

11. DEBAJITO DEL PUENTE (Manolo Caracol) 2’21

12. TIENTOS (Niño de Almaden) 3’57

13. VERDIALES (Bernardo el de los Lobitos) 3’01

14. SEVILLANAS CORREALES (Bernardo el de los Lobitos) 2’56

15. ALEGRIAS (Pericon de Cadiz) 2’54

16. SOLEARES (Pepe de la Matrona) 3’23

17. CANTES DE TRILLA (Bernardo el de los Lobitos) 1’37

18. PETENERA (Rafael Romero) 3’33

19. NANAS (Bernardo el de los Lobitos) 3’26

20. GYPSY LULLABYE (Pastora Amaya) 2’09