- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

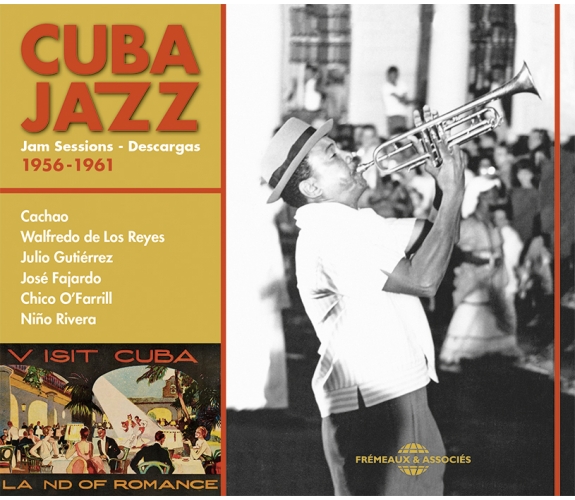

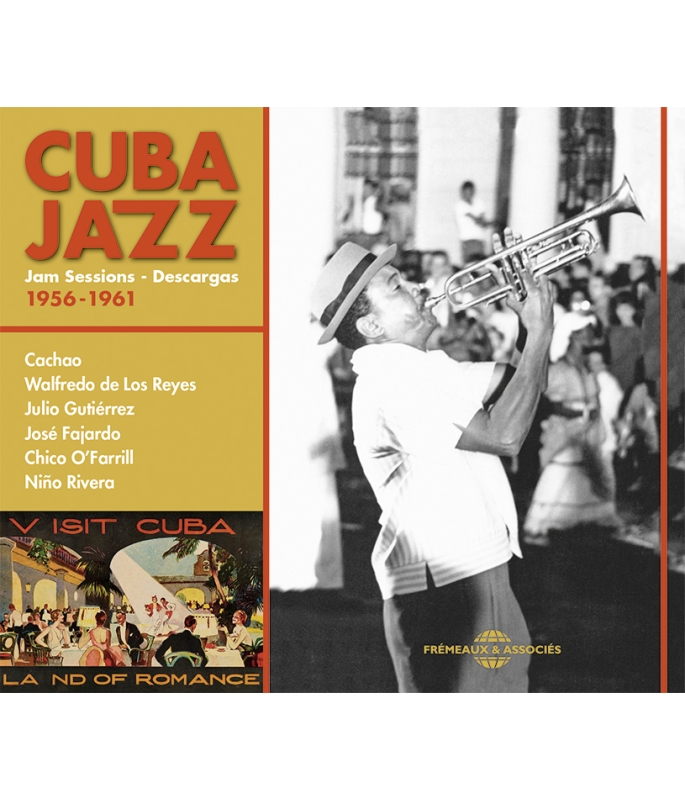

JAM SESSIONS - DESCARGAS 1956-1961

CACHAO • WALFREDO DE LOS REYES • JULIO GUTIÉRREZ • JOSÉ FAJARDO • CHICO O’FARRILL • NIÑO RIVERA

Ref.: FA5722

EAN : 3561302572222

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JAM SESSIONS - DESCARGAS 1956-1961

JAM SESSIONS - DESCARGAS 1956-1961

Recorded right before the revolution, at the heart of the golden age of Cuban Music, the original «descargas» unleash the spiritual power of repetitive trance. They blend inspired improvisations, the inner ¬ re of hypnotising choruses propelled by local rhythms and demented percussions. Cachao and his friends brought the cream of the island’s musicians together to cut some of Cuban music’s ¬ nest moments: the steadfast, founding “Cuban Jam Sessions” classics. Bruno Blum tells their legend in a 28-page booklet. Indispensable to any enlightened jazz enthusiast. Featuring Oreste López, Peruchín, Emilio Peñalver, Tata Güines, Chuchu, Tojo, Guillermo Barreto, Chombo Silva, Óscar Valdés, Mosquifin, El Negro Vivar… Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Descarga CalienteJulio Gutierez y OrchestraJ. Gutierrez00:16:162018

-

2Cuba Jazz Jam SessionsJulio Gutierez y OrchestraJ. Gutierrez00:00:302018

-

3Theme On PerfidiaJulio Gutierez y OrchestraAlberto Dominguez00:08:282018

-

4Theme On MamboJulio Gutierez y OrchestraOrestes Lopez Valdez00:03:312018

-

5CimarrónJulio Gutierez y OrchestraPapo Vasquez00:06:282018

-

6Oye Mi Ritmo Cha Cha ChaJulio Gutierez y OrchestraJ. Gutierrez00:04:492018

-

7Opus For DancingJulio Gutierez y OrchestraJ. Gutierrez00:10:202018

-

8Trombón CriolloCachao y su ComboGerardo Portillo00:03:092018

-

9Controversia de MetalesCachao y su ComboCachao00:03:002018

-

10Estudio en TrompetaCachao y su ComboCachao00:02:232018

-

11Guajeo de SaxosCachao y su ComboEmilio Penalver00:02:252018

-

12Oye Mi Tres MontunoCachao y su ComboAndres Echevarria00:02:432018

-

13Malanga AmarillaCachao y su ComboSilvio Contreras00:03:162018

-

14Cógele en GolpeCachao y su ComboA. Castillo Jr00:02:452018

-

15PamparanaCachao y su ComboAlfredo Leon00:02:362018

-

16Descarga CubanaCachao y su ComboOsvaldo Estivill00:03:042018

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Goza Mi TrumpetaCachao y su ComboOsvaldo Estivill00:02:592018

-

2A Gozar TimberoCachao y su ComboOsvaldo Estivill00:03:022018

-

3Sorpresa de FlautaCachao y su ComboOsvaldo Estivill00:02:482018

-

4Oguere Mi ChinaCachao y su Orquestra CubanaInconnu00:03:232018

-

5El Manisero The Peanut VendorCachao y su Orquestra CubanaRodriguez Moises Simons00:03:032018

-

6Descarga MamboCachao y su Orquestra CubanaInconnu00:05:032018

-

7Descarga GuajiraCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:05:502018

-

8La InconclusaCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:03:292018

-

9RedenciónCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:03:132018

-

10La LuzCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:04:402018

-

11OleCachao y su ConjuntoEnemelio Jimenez00:04:342018

-

12A Gozar Con el ComboCachao y su ConjuntoEnemelio Jimenez00:04:272018

-

13A Gozar TimberoCachao y su ConjuntoOsvaldo Estivill00:03:022018

-

14PamparanaCachao y su ConjuntoAlfredo Leon00:02:432018

-

15Es DiferenteWalfredo de los Reyes & His All-StarsOreste Lopez Valdes00:02:502018

-

16Mucho HumoWalfredo de los Reyes & His All-StarsCachao00:03:182018

-

17Descarga MexicanaCachao y su ComboCachao00:04:562018

-

18Descarga NanigaCachao y su ComboInconnu00:05:122018

-

19Popurrí de CongasCachao y su ComboInconnu00:05:382018

-

20Descarga GeneralCachao y su ritmo calienteCachao00:03:382018

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Montuno GuajiroNino Rivera's Cuban All StarsNino Rivera00:09:232018

-

2Cha Cha Cha MontunoNino Rivera's Cuban All StarsNino Rivera00:08:532018

-

3Cha Cha Cha de los PollosWalfredoTito Puente00:02:462018

-

4Las Boinas de CachaoWalfredo de los Reyes & His All-Stars BandCachao00:02:582018

-

5Leche Con RonWalfredo de los Reyes & His All-Stars BandPaquito Echevarria00:02:562018

-

6El Fantasma del ComboCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:05:172018

-

7El Bombín de PeruchoCachao y su ConjuntoCachao00:04:292018

-

8Juan Pescao Tea For TwoCachao y su ConjuntoI. Caesar00:02:522018

-

9Avance JuvenilCachao y su ConjuntoBuenaventura Lopez00:03:162018

-

10La FlorestaCachao y su ConjuntoOreste Lopez Valdes00:02:432018

-

11Rumba SabrosaCachao y su ConjuntoOreste Lopez Valdes00:05:042018

-

12Pa Coco SoloFajardo & His All StarsJose Fajardo00:03:552018

-

13El Viejo YumbaRolando Aguilo y su EstrellasRolando Aguilo00:02:312018

-

14Descarga Tea For TwoRolando Aguilo y su EstrellasI. Caesar00:03:342018

-

15La Última NocheRolando Aguilo y su EstrellasB. Collazo00:03:172018

-

16Descarga CriollaRolando Aguilo y su EstrellasRay Barretto00:03:292018

-

17Descarga Número UnoChico O'Farrill y All Stars CubanoChico O. Farrill00:02:592018

-

18Descarga Número DosChico O'Farrill y All Stars CubanoChico O. Farrill00:02:522018

-

19BilongoChico O'Farrill y All Stars CubanoGuillermo Rodriguez Fiffe00:02:552018

fa5722 Cuba Jazz

CUBA

JAZZ

Jam Sessions - Descargas

1956-1961

Cachao

Walfredo de Los Reyes

Julio Gutiérrez

José Fajardo

Chico O’Farrill

Niño Rivera

CUBA JAZZ

Jam Sessions - Descargas 1956-1961

par Bruno Blum

À la suite de différentes expériences où la musique cubaine et le jazz états-unien se sont mélangés et rapprochés à New York et à La Havane, le genre jazz « descarga » a éclos sur disque. Après le succès de deux albums de jam sessions de José Gutiérrez commandés par Ramón Sabat, producteur et propriétaire des disques Panart à La Havane, de nouvelles descargas en studio ont été enregistrées. Elles ont été dominées par diverses formations réunies par Israel « Cachao » López. Nombre de musiciens de premier choix y ont participé, dont Chico O’Farrill, qui avait travaillé sur des enregistrements cubains avec Charlie Parker à New York. La période des descargas de 1956-1961 représente un sommet de créativité inégalé depuis dans l’île. La musique locale n’a jamais retrouvé ce souffle après la nationalisation de Panart et de ses studios en 19601, mais la descarga originelle avait déjà profondément influencé la musique cubaine qui allait donner naissance à la salsa une décennie plus tard. Les descargas ont aussi inspiré de nouvelles productions dans cette veine, notamment aux États-Unis. Elles ont donné une nouvelle dimension à la musique cubaine, caribéenne et à l’utilisation des congas, des timbales et des bongos. Le premier album publié sous le nom de Cachao, Descargas Cubanas de 1957 reste l’un des chefs-d’œuvre de la culture du pays.

Le jazz, musique des Caraïbes

Selon les stéréotypes habituels, le jazz est une musique multiforme, très variée, apparue au début du XXe siècle dans le sud des États-Unis et à la Nouvelle-Orléans en particulier, où il s’est développé avant de gagner le continent nord-américain par le Mississippi. Il est peut-être bon de rappeler que le terme « jazz » était récusé par Miles Davis, qui lui préférait le terme de « musique » car « jazz » était racialement connoté. En effet ce mot désignait fondamentalement une musique rythmée, de culture créole (créole = mélange d’éléments européens, africains et amérindiens devenus une culture à part entière, distincte de ses racines) à laquelle est fait allusion ici dans Trombón Criollo. Or ces musiques créoles rythmées et dansantes, si particulières, étaient présentes dans toutes les Caraïbes. À Cuba les cultures africaines ont été bien mieux pérennisées qu’aux États-Unis. En ce sens le jazz est la musique de toutes les Caraïbes et la Nouvelle-Orléans est avant tout, culturellement et géographiquement, une ville des Caraïbes, une ville créole — comme La Havane.

À l’exception de la Nouvelle-Orléans, les cultures africaines ont été strictement interdites et dévalorisées pendant des siècles sur le continent nord-américain où elles furent en bonne partie perdues. Or la Nouvelle-Orléans et la Louisiane partagent un lien très fort avec Haïti et Cuba (immigration, commerce, échanges divers au XIXe et XXe siècles) et les groupes de charanga cubains des années 1910-1940 jouaient des musiques dansantes mélangeant différents styles créoles. Ces petits ensembles populaires cubains interprétaient des musiques influencées par Haïti, la France, l’Espagne et l’Afrique dans leurs répertoires de contredanse, de chanson, de son et de danzón. Après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, ils ont évolué vers le cha cha chá puis la salsa. Ils étaient, à leur manière cubaine, une incarnation du jazz du début du vingtième siècle, rythmé, populaire et propice à des passages instrumentaux parfois improvisés, comme dans la musique de Fletcher Henderson ou Jelly Roll Morton. Bien que différentes des musiques états-uniennes, les musiques cubaines ont fait leur chemin dans le siècle main dans la main avec celles venues du continent. Et le jazz, en tant que musique de toutes les Caraïbes, a connu une de ses plus belles pages à Cuba : la descarga des années 1950.

Il y a de la rumba dans l’air

C’est en 1930 que la chanson El Manisero (« The Peanut Vendor », dont figure ici une version) de Moisés Simón Rodriguez a été mise en scène à Broadway par Antonio Machin et Don Azpiazu, avant que cette composition au style son distinctement cubain ne se propage dans le monde entier. Les musiques des Caraïbes commençaient doucement à avoir un impact international ; plusieurs productions avaient déjà fait surface à Trinité-et-Tobago au sud, et à New York où enregistraient nombre de musiciens venus de la Caraïbe (le premier disque enregistré à la Trinité date de 1912 et les Trinidadiens Lionel Belasco et Sam Manning ont beaucoup enregistré à New York). À commencer par des artistes venus du sud des États-Unis (premier disque de jazz états-unien : 1917, gravé à New York). Ces musiques créoles étaient enfin mises en valeur et se faisaient une petite place dans le paysage musical occidental. Les musiques créoles caribéennes étaient perçues comme salaces (écouter Ruth Wallis, qui joue ouvertement cette carte sur Caribbean in America dans cette collection) ; pour le grand public elles évoquaient principalement le tourisme sexuel, les tenues légères et détenaient un attrait par le divertissement qui différait de la ligne dure ségrégationniste en vigueur dans tous les États-Unis. Le Cubain était parfois perçu comme un étalon bronzé propice à des rencontres sans lendemain et sa musique incitant à la danse était comme une invitation troublante, exotique et coupable, osée mais attirante. Ce qui a provoqué des adaptations à l’étranger2. En France la carrière de Tino Rossi, chanteur de charme « exotique » a été lancée en 1936 par le film Marinella et sa chanson du même nom, au rythme rumba cubain. Comme Porto Rico, Cuba était littéralement devenu une colonie des États-Unis et l’interaction culturelle entre les deux pays se développait. Une partie de la clientèle aisée des lieux de divertissements de La Havane était composée de citoyens américains : soldats, hommes d’affaires, entrepreneurs en hôtellerie, couples de retraités, aventuriers et touristes venus s’encanailler. La Havane était un lieu de fête, de spectacles, de cabarets, de casinos, de triomphe du dollar et de l’esprit colonial au milieu de la misère. À partir de 1924 (alors que la Prohibition de l’alcool était en vigueur aux États-Unis de 1920 à 1933), le développement du tourisme à Cuba engendra une demande sans précédent d’alcool, de spectacles, de prostitution et de jeu. L’architecture, le soleil et la musique faisaient partie de l’attrait du pays3. Un marché pour la musique cubaine s’est ainsi ouvert ; la popularité de la rumba commençait à grandir et quelques musiciens cubains sont partis s’installer aux États-Unis en quête d’une vie meilleure. Machito, un chanteur de La Havane, partit s’installer à New York en 1937. Il y a fondé un orchestre cubain en 1940. À Cuba, la musique évoluait vers de nouvelles formes4 et Cachao était l’une de ses forces créatrices.

Cachao

Cachao fut le grand contrebassiste cubain du vingtième siècle et l’un des artistes les plus essentiels venus de Cuba. Compositeur et arrangeur extrêmement prolifique, il a dirigé plusieurs formations et jouait de plusieurs instruments. Il fut l’un des musiciens cubains les plus importants, l’un des plus influents et des plus innovants, renouvelant avec son grand frère le violoncelliste Orestes « Macho » López le danzón traditionnel en « ritmo nuevo » et fondant avec lui rien moins que le genre mambo à la fin des années 1930 dans le groupe du flûtiste Antonio Arcaño, l’Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas. Cachao fut aussi l’un des talents majeurs du genre descarga, l’équivalent cubain du jazz moderne, objet de ce coffret qui contient 35 titres dirigés par lui.

Israel « Cachao » López (La Havane, 14 septembre 1918-Miami, 22 mars 2008) est né dans la maison où naquit le poète révolutionnaire José Marti. Il était le plus jeune des enfants d’une grande famille de musiciens où figurait, selon les estimations, entre trente et cinquante bassistes. Ses parents, son célèbre frère Orestes et sa sœur Corelia avaient maîtrisé la contrebasse avant lui et les séances de répétitions quotidiennes dans la maison familiale de La Havane étaient un divertissement pour le quartier. Orestes jouait d’une dizaine d’instruments ; Cachao son petit frère a étudié le piano classique et la composition pendant des années avant de décrocher son premier engagement professionnel au sein de l’ensemble de Bola de Nieve, qui jouait dans les cinémas de La Havane pour mettre de l’ambiance pendant les films muets. En 1930 il a été engagé comme contrebassiste de l’Orchestre Philharmonique de La Havane cofondé par le grand frère Orestes en 1924 ; trop petit pour la contrebasse à l’âge de douze ans, il devait monter sur une caisse pour pouvoir jouer.

Cachao s’est imposé comme l’un des grands arrangeurs et compositeurs cubains. À dix-sept ans en 1937 il a rejoint le groupe de charanga (musique populaire dansante, associée à la tradition du style danzón) du flûtiste Antonio Arcaño. À vingt-deux ans il avait composé avec son frère Orestes environ deux mille cinq cents danzóns, le style traditionnel, amalgame de rythmes africains et de musique de bal espagnole. Toujours avec Orestes, Cachao participa à la création du mambo, un nouveau rythme et un nouveau style qui ferait fureur aux États-Unis dans l’après-guerre avec Pérez Prado5. Le mambo est ainsi né de l’incorporation dans le danzón traditionnel (violon, cuivres et timpani) de passages plus rythmés, plus africains et syncopés, le « ritmo nuevo »6. Cette création fut dérivé dès 1937 d’un rythme tumbao cubain que Cachao joua à Orestes au sein de l’Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas. La chanson fondatrice « Mambo » (« prêtresse vaudou » à Haïti) de Cachao et Orestes en 1939 évoque la spiritualité afro-cubaine (santería et lucumí) mais elle comprend aussi des phrases courtes, répétitives, ces riffs d’instruments à vent (et du violoncelle d’Orestes López) analogues à ceux du jazz des orchestres de la période swing7.

Dans les années 1940 le terme descarga (« déchargement ») était déjà utilisé pour décrire les boléros interprétés dans un style influencé par le jazz, avec des improvisations (le boléro cubain est lent et interprété par des séducteurs chantant l’amour). À la fin de la décennie la très populaire chanson romantique cubaine, la canción, et le boléro au tempo lent, ont développé cette approche plus large : une tendance qui laissait plus de place aux solistes, sous le nom de filín ou feelín. Trompettiste exceptionnel, El Negro Vivar était un pilier de ces bœufs au Tropicana, qui prenaient place après les concerts qu’il y donnait plus tôt dans la soirée. On le retrouve ici sur de nombreux titres.

Le style filin’ était une forme de jazz cubain. Enracinée dans la tradition des poètes troubadours (la trova) qui s’accompagnent à la guitare, la tendance filín a continué pendant quelques années et s’est étiolée après la révolution de 1959. Avec les nouvelles formations de type « conjunto » et l’influence américaine, la musique cubaine était entrée dans une nouvelle phase.

Panart

La principale et première vraie maison de disques cubaine, Panart (contraction de « Panamerican Art ») a été fondée en 1944 par le musicien et ingénieur Ramón S. Sabat (1902-1986), qui avait étudié la clarinette, la flûte, le piano et le saxophone à Cuba avec José Rivero Rodríguez. Sabat est parti étudier la musique aux États-Unis en 1919. Engagé dans l’armée des États-Unis il fit partie d’un groupe de militaires musiciens puis travailla dans plusieurs maisons de disques new-yorkaises avant de rentrer à Cuba où il devint producteur en 1943. Le nom de ses studios Areíto est venu d’un terme taïno (les amérindiens indigènes des Caraïbes) décrivant les chorégraphies et cérémonies musicales rituelles qui rendaient hommage aux exploits des chefs, des divinités et des cemi, les esprits des ancêtres. Nationalisés en 1961 avec la marque Panart qui s’est installée à Miami, ces studios légendaires sont toujours situés au n°410 de la Calle San Miguel dans le centre historique de La Havane.

La diffusion de disques cubains dans l’après-guerre a permis de séduire les autres pays hispanophones de la région Caraïbe dont le Venezuela, la Colombie, le Mexique, Porto Rico et Saint-Domingue. Les disques cubains (danzon, bolero, rumba, son, etc.) ont alors commencé à circuler plus largement aux proches États-Unis. Certains musiciens de jazz états-uniens comme Dizzy Gillespie ont alors vu en Cuba une façon de renouer avec les inaccessibles cultures originelles d’Afrique dont on trouve des traces profondes dans les rituels de la santería, du lucumí yoruba et les percussions de la rumba, du bata8. Le titre Ogueré Mi China ici est par exemple une invocation à l’orisha yoruba Shangô et Potpurrit de Congas donne un aperçu de l’intensité des rituels animistes, qui étaient capables de provoquer des transes. Sur Mucho Humo, des improvisations de trompette, piano et flûte sont plaquées sur des percussions rumba traditionnelles dans un esprit très libre. Inversement, le professionnalisme, la créativité et le style des orchestres de jazz états-uniens ont marqué le merengue dominicain9, le compas haïtien10, le jazz jamaïcain11 autant que les musiciens de La Havane et bien d’autres musiciens professionnels aux caraïbes.

Ramón Sabat développa rapidement les disques Panart. À la suite du succès grandissant du merengue dominicain et du mambo de Pérez Prado aux États-Unis à partir de 1949, en 1952 Sabat décrocha un contrat de distribution à l’étranger avec Decca. Il était concurrencé par RCA Victor à New York mais resta le principal producteur de l’île. Ses disques ont bientôt été distribués par Capitol à Hollywood ; il avait dans son écurie quelques-uns des meilleurs artistes de son montuno du pays, les nouveaux groupes qui remplaçaient les formations charanga du passé, dont Conjunto Casino (avec l’arrangeur, compositeur et joueur de tres Niño Rivera, dont deux titres très influencés par le son montuno ouvrent le disque 3). Le son montuno de Panart incluait aussi Orquesta Sublime, Conjunto Marquetti, Conjunto Chapottin, Orquesta Novedades, Orquesta Rey Diaz Calvet et le groupe de Compay Secundo, qui deviendrait célèbre au sein du Buenavista Social Club en 199912. Sabat détenait l’exclusivité de formations ambitieuses et professionnelles comme La Sonora Matancera, Julio Gutiérrez et son orchestre, et l’équipe de Cachao, qui travaillait à la fois avec le Philharmonique et l’Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas.

Caribbean in America

À New York, le groupe de Machito a enregistré avec Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker et d’autres musiciens de jazz de haut niveau. La musique cubaine commençait à être acceptée aux États-Unis, notamment car les géants du jazz moderne à New York la considéraient être une forme de musique afro-américaine de haut niveau comme la leur. Ils y retrouvaient aussi des rythmes ternaires (swing) courants dans le jazz des États-Unis. Les premiers succès américains du calypso trinidadien (reprise à succès de « Rum and Coca-Cola » par les Andrews Sisters en 1944 et bientôt le triomphe du mento jamaïcain de Harry Belafonte en 195613), la mode du mambo cubain avec Pérez Prado à partir de 1949, du merengue dominicain d’Angel Viloria avec Doris Valladares à partir de 1950, puis du cha cha chá cubain étaient principalement le fait d’une diaspora caribéenne qui enregistrait à New York. L’orchestre de Tito Puente (né à New York) jouait par exemple du mambo à New York comme à Los Angeles. Cette période très riche est documentée dans nos coffrets Caribbean in America 1915-196214, Roots of Mambo 1930-195015 et Cuba in America 1939-196216. Le 21 décembre 1950, Charlie Parker enregistrait pour Norman Granz « Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite » composé par Dizzy Gillespie et Chano Pozo avec un orchestre de vingt personnes dirigé par l’expatrié cubain Chico O’Farrill17. Chico collaborerait aussi avec Dizzy sur « Manteca Theme » (24 mai 1954). Il était spécialisé dans les orchestrations sophistiquées, qui ont influencé par exemple Cuban Fire!, un succès de l’orchestre de Stan Kenton enregistré à New York en 1956. Bien que sortie à l’origine sous le nom de Cuban Jam Sessions, et bien qu’il contienne des rythmes afro-cubains, la contribution de Chico O’Farrill qui clôt ce coffret relève plus d’un jazz pour orchestre (type swing), répondant à celui de Dizzy Gillespie, que de l’improvisation plus informelle, telle que Cachao ou Julio Gutiérrez le proposent ici. Il indique une des voies que prendrait la musique cubaine par la suite. Pendant ce temps, le new-yorkais Tito Puente enregistrait des succès de mambo instrumental comme « Ran Kan Kan » (1955), où figurent de longs solos de xylophone18.

En 1952 le producteur de jazz new-yorkais Norman Granz fit réaliser à La Havane une séance de jazz avec le percussionniste Jack Costanzo (sur une face), Bebo Valdés, héritier de la tendance feelín (sur l’autre) et d’autres musiciens locaux : sorti sous le nom de Andre’s All Stars, l’album Cubano (sorti en 1956) constitue une étape importante dans le développement du jazz cubain. Inévitablement, les musiciens restés à Cuba rêvaient de bénéficier à leur tour de cette popularité internationale, qui leur échappait.

Descarga

Panart exportait aux États-Unis où la fusion jazz/musique cubaine de Machito, Chano Pozo, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Chico O’Farrill, Mongo Santamaria, Cal Tjader, Slim Gaillard, Stan Kenton ou encore Tito Puente et maintenant Bebo Valdés et Jack Costanzo suscitait de plus en plus d’intérêt. C’est donc tout naturellement que Ramón Sabat a demandé à l’un de ses meilleurs orchestres d’enregistrer une descarga, en anglais jam session, en français « un bœuf ». José Gutiérrez avait dirigé l’Orquesta Casino de la Playa à partir de 1941 (avec un temps Perruchín au piano) avant de monter son propre groupe. Depuis 1948 il dirigeait son propre orchestre avec le percussionniste Óscar Valdés, le saxophoniste Emilio Peñalver et le trompettiste « El Negro » Vivar, des musiciens de premier plan qui brillent ici. Gutiérrez accompagnait aussi différents artistes pour la télévision.

Le José Gutiérrez Orquesta a enregistré Descarga Caliente, le premier titre du nouveau genre descarga jamais gravé, au studio Areíto vers 1956. Après une deuxième séance de studio (avec un petit public présent), Panart l’a sorti cette même année. Les morceaux étaient informels, in extenso, parfois un peu longs, mais l’album, bien que voulu commercial, a obtenu un succès critique inattendu et s’est bien vendu.

Comme dans les boîtes états-uniennes, les meilleurs musiciens de La Havane se retrouvaient pour jouer ensemble et improviser dans l’esprit du jazz tard la nuit, après leurs engagements payés (le Tropicana était l’un des lieux branchés de La Havane pour faire le bœuf, avant que le Bambú ne le concurrence après 1956).

En 1956 en plus de différentes revues et de l’orchestre d’Antonio Arcaño avec lequel il avait introduit le rythme mambo vingt ans plus tôt, Cachao participait à l’orchestre de José Fajardo, qui a aussi enregistré des descargas. Il retrouvait ses collègues et amis musiciens vers quatre heures du matin pour improviser et tout mélanger sur des rythmes et suites d’accords caractéristiques de la musique cubaine. Les descargas du styliste Cachao empruntaient l’usage des bongos, du tres et de la trompette aux groupes de son. On y retrouvait les appels-réponses de la rumba et du son montuno, la flûte, la percussion de bois guiro (idiophone) et les tambours paila au groupes de charanga et de danzón, sans oublier les saxophones et le trombone du nouveau jazz cubain en plein essor. La crème des virtuoses du pays ont inventé ensemble cette nouvelle étape de leur musique. La première et excellente descarga de Cachao y su Combo a été enregistrée la nuit, après le travail en scène, dans les conditions d’un bœuf mais au studio Areíto. Elle est sortie chez Panart en 1957 sous le titre de Cachao y su Combo, Descarga Cubanas (disque 1, titres 8-16 et disque 2, titres 1-3). Il est paru aux États-Unis en 1961 sous le nom de Cachao y su Ritmo avec pour titre Cuban Jam Sessions in Miniature, car les titres étaient beaucoup plus courts que les improvisations habituelles en scène. Ce fut le premier album de Cachao sorti sous son nom.

On peut écouter ici des musiciens cubains légendaires comme le pianiste Pedro « Perruchín » Jústiz, qui a appris le piano de sa mère, dans une famille de musiciens. C’est dans l’orchestre de trova Los Trovadores del Tono qu’il a rencontré Chombo Silva et l’a encouragé à apprendre le saxophone, un instrument que Perruchín avait dû abandonner en raison de son asthme. Le pianiste avait collaboré avec Julio Gutiérrez en 1941 avant de rejoindre en 1942 l’orchestre Los Swing Boys où il joua avec le saxophoniste Emilio Peñalver. Chombo Silva était entretemps devenu un maître du sax, mais leurs engagements divers ne réunissaient pas tous ces virtuoses dans la même formation. Tous ces musiciens prestigieux se connaissaient bien et se sont enfin retrouvés ici par la magie d’une collaboration au sommet dans l’esprit impromptu et spontané du jazz.

Perruchín avait rejoint une multitude de forma-tions de premier plan, dont le célèbre grand orchestre de Beny Moré en 1953, mais cela ne l’a pas empêché de graver ces improvisations avec Julio Gutiérrez et Cachao. Tata Güines, « Le Roi des Congas », est venu de Güines, une petite ville pauvre au sud de La Havane où il avait appris les rythmes en tapant sur des cartons. À la vingtaine il était déjà reconnu comme l’un des meilleurs joueurs de congas de l’île, les tumbaderos, et a accompagné les plus grands. Le batteur Walfredo de los Reyes (troisième du nom) Junior était le fils d’un grand trompettiste. Il accompagnait Julio Gutiérrez lors de ses passages télévisés sur Channel 4 ; il frappe ici parfois des timbales d’une main et des congas de l’autre. L’exceptionnel trompettiste El Negro Vivar jouait le jazz bop en plus de la musique cubaine. Il a lui aussi fait partie de « l’orchestre géant » de Beny Moré et ne ratait pas une descarga de fin de soirée au Tropicana, où il jouait en soirée. Il est présent sur un grand nombre des titres de ce coffret.

Peu d’informations ont fait surface sur tous ces enregistrements, réalisés en quelques nuits à La Havane à une époque où la musique cubaine était peu documentée. Comme certains des autres titres inclus ici plusieurs classiques de Cachao sont difficiles ou impossibles à dater avec précision (1957-1959), sachant que comme beaucoup de musiciens Cachao a quitté le pays en 1961 à la suite de la révolution communiste — et de la nationalisation de Panart ; les crédits des musiciens sont donc susceptibles d’inexactitudes et de flous. Il n’en demeure pas moins que ces enregistrements sont d’une grande originalité et qu’ils ont beaucoup inspiré quelques grands noms de la musique états-unienne comme Cal Tjader, Carlos Santana, Tito Puente, Lalo Schifrin, Xavier Cugat et la salsa qui allait bientôt naître à New York. Ce coffret rend justice à ces enregistrements négligés, presque oubliés. Et si la qualité et l’importance historique de la fusion expérimentale jazz new-yorkais/musique cubaine parue aux États-Unis (Charlie Parker, Machito, Dizzy Gillespie, etc.) ne sont pas à mettre en doute, l’authenticité du jazz cubain pur, véritable, dont on peut apprécier ici quelques-uns des sommets originels, est aussi irremplaçable qu’incomparable.

Bruno Blum, février 2018

Merci à Crocodisc, Lola Delaire, Franck Jacques, Philippe Lesage et Roger Steffens.

© Frémeaux & Associés 2018

1. Lire le livret et écouter notre coffret de quatre disques Retrospective des musiques cubaines 1981-1997 dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Amour bananes et ananas, antho-logie de la chanson exotique dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret d’Olivier Cossard et Helio Orovo et écouter Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937 dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret d’Isabelle Leymarie Cuba 1923-1995 dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret de Pierre Carlu et écouter Mambo - Big Bands 1946-1957 dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret de Bruno Blum et écouter Roots of funk 1947-1962, qui contient plusieurs titres cubains syncopés, dans cette collection.

7. La version originale de la chanson «Mambo» par Antonio Arcaño y sus Maravillas est disponible sur Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba - Santería, Lucumí, Regla de Ochá, Regla de Ifá, Batá rituals à paraître dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic - Merengue, Haiti Cuba Virgin Islands Bahamas New York 1949-1962 dans cette collection.

10. Lire le livret et écouter Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 dans cette collection.

11. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba-Son Montuno 1944-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Harry Belafonte - Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 dans cette collection.

14. Lire le livret et écouter Caribbean in America 1915-1962, qui montre dans cette collection la rencontre musicale entre musiques caribéennes et états-uniennes.

15. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 dans cette collection.

16. Lire le livret et écouter Cuba in America 1939-1962, qui montre dans cette collection la rencontre musicale entre musiques cubaines et états-uniennes.

17. «Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite» par Machito et son orchestre avec Charlie Parker, dirigé par Chico O’Farrill est disponible dans le volume 9 de l’intégrale de Charlie Parker dans cette collection. D’autres titres réunissant ces artistes figurent dans le volume 8.

18. La version originale de «Ran Kan Kan» figure sur Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 dans cette collection.

CUBA JAZZ

Jam Sessions - Descargas 1956-1961

By Bruno Blum

Following various experiments, where Cuban music and US jazz got closer to each other, blending in New York as well as Habana, the “descarga” jazz genre finally hatched out on record.

After two successful 1956 jam sessions albums by José Gutiérrez’ group, both ordered by Ramón Sabat, founder and owner of Panart Records in Havana, some more descargas were recorded in the studio. The best ones were arguably played by various bands put together by Israel “Cachao” López. Several first choice musicians contributed, including Chico O’Farrill, who’d worked on Cuban recordings featuring Charlie Parker in New York City.

The 1956-1961 descargas wave embodies a creative peak that has remained unmatched on the island ever since.

Local music was never the same again after Panart Records and their studios were nationalized in 19601, but vintage descarga had already deeply influenced Cuban music, which was to give birth to salsa a decade later.

The descargas have also inspired new productions in this vein, most notably in the US. They have given Cuban and Caribbean music, as well as congas, timbals and bongos, a new dimension. The first album released under Cachao’s name, Descargas Cubanas in 1957, remains a masterpiece of the country’s culture.

Jazz is Caribbean music

According to the usual stereotypes, jazz is a very varied, multiform music surfacing in the South of the USA in the early twentieth century, mostly in New Orleans, where it developed and then spread to the rest of the American continent, travelling north on the Mississippi river. However, it might be useful to remind the listener of this following fact: The term “jazz” was declined by Miles Davis, who preferred the word “music”, as “jazz” implied a racial bias. The word in fact meant a form of rhythmic music bred in Creole culture (Creole means a mix of European, African and Native Indian elements that have become a separate culture, distinct from its roots) alluded here in Trombón Criollo.

Yet these peculiar Creole rhythm musics were found all over the Caribbean. African cultures were way more preserved in Cuba than they were in the USA. In this sense, jazz is therefore the music of all of the Caribbean and New Orleans is first and foremost a Caribbean city, both geographically and culturally: it is a Creole city —just like Havana.

Except in New Orleans, African cultures were put down and strictly prohibited for centuries on the North American continent, whereby much of these cultures was lost. However, New Orleans and Louisiana shared a very strong bond with Haiti and Cuba.

This involved immigration, trade & various cultural exchanges in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cuban charanga bands of the 1920s and 1940s were playing dance music that mixed several Creole styles.

These small, popular Cuban bands performed Haitian, French, Spanish and African-influenced music in their contredanse, son, danzón and song sets. After WWII, they moved on to cha cha chá and later salsa. In their own Cuban way they were an embodiment of early, popular twentieth century jazz with rhythm, instrumental parts and sometimes improvisation, as in Fletcher Henderson or Jelly Roll Morton’s music of the time.

Although different from US music, Cuban music walked its way through that century hand in hand with sounds from the continent. And jazz music, as the Caribbean’s own, had experienced one of its most beautiful episodes in Cuba: the 1950s’ descarga.

Rumba Sabrosa

In 1930, Moisés Simón Rodriguez’ song El Manisero (aka “The Peanut Vendor,” of which one version is included here) was staged on Broadway by Antonio Machin and Don Azpiazu, before this distinctly Cuban, son-styled composition spread out worldwide.

Caribbean music was now slowly beginning to become international; several productions had surfaced south in Trinidad and Tobago, as well as in New York City, where many Caribbean musicians recorded. (The first tune recorded in Trinidad goes back to 1912 and Trinidadians Lionel Belasco and Sam Manning made many records in New York).

Starting with musicians from the US Deep South (the first US jazz record was made in New York City in 1917) Creole musics were being shown in a more attractive light finally, and they had now become a small niche market in the wider Western musical landscape. Caribbean Creole music was often perceived as salacious (hear Ruth Wallis, who openly played it risqué on Caribbean in America in this series); to a wide audience, it brought to mind sexual tourism, skimpy clothing and possessed an attraction best described as the power of entertainment. This contrasted dramatically with the segregationist hard line in effect all around the United States. Cubans were sometimes seen as suntanned stallions suitable for quick dating, and their dance-oriented music was like an arousing, exotic and guilty invitation, both daring and appealing. It triggered some foreign adaptations2.

In France the career of “exotic” crooner Tino Rossi was launched in 1936 with the film Marinella and its song of the same name, which was sung to a Cuban rumba beat.

Like Puerto Rico, Cuba had literally become a US colony and cultural interplay was growing stronger between the two countries. A portion of the well-off customers in Havana’s entertainment venues were US citizens: soldiers, businessmen, hotel entrepreneurs, retired couples, adventurers and tourists who came to slum it.

Havana was a party land amidst poverty, complete with musical shows, nightclubs & casinos, where the dollar talked triumphantly and colonial spirit ruled. As from 1924 (alcohol Prohibition was applicable in the USA from 1920 until 1933), growing tourism in Cuba demanded more alcohol, shows, prostitution and gambling.

Architecture, sunshine and music were part of the country’s attraction3. Thus a market for Cuban music had opened; rumba’s popularity was growing and a few Cuban musicians migrated to the US in search of a better life.

Havana singer Machito moved to New York City in 1937. He founded a Cuban Orchestra there in 1940. Meanwhile, in Cuba, music was evolving into new forms4 and Cachao was one of its greatest creative assets.

Cachao

Cachao was the greatest Cuban double-bass player of the twentieth century and one of the most essential musicians ever to come out of Cuba. An extremely prolific composer and arranger, he played several instruments and directed several bands. He was one of Cuba’s most important, most influential and innovative musicians.

With his brother, cello player Orestes “Macho” López, he updated the traditional danzón into “ritmo nuevo” and, also with Orestes, founded no less than the mambo genre at the end of the 1930s, when they were members of flutist Antonio Arcaño’s band, Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas.

Cachao was also a major talent in the descarga genre, the Cuban equivalent of modern jazz, which this set is all about — and which contains 35 tracks led by him.

Israel “Cachao” López (Havana, Septembre 14, 1918 - Miami, March 22, 2008) was born in the very house where revolutionary poet José Marti was also born. He was the youngest of a great family of musicians which, depending on which estimate you believe, included from thirty up to fifty bass players.

His parents, his famous brother, Orestes, and his sister, Cordelia, had mastered the double bass before him and daily rehearsals in their Havana family house entertained the neighbourhood. Orestes played at least ten instruments; Cachao, his little brother, had studied classical piano and composition for years before he got his first professional job, in Bola de Nieve’s band, which played atmospheric music during silent films in Havana’s movie theatres. By 1930 he was hired as the bassist in Havana’s Philharmonic Orchestra, which was founded by his brother, Orestes, in 1924; aged only twelve, he was too small to play the double bass and needed to stand on a box to be able to play.

In Havana Cachao established himself as one of the great Cuban arrangers and composers. In 1937, aged seventeen, he joined flutist Antonio Arcaño’s charanga band (popular dance music, associated with the danzón style tradition). By the time he was twenty-two he and his brother had composed around 2,500 danzóns in the traditional style, which amalgamated African rhythms and Spanish ball music. Also, with Orestes, Cachao contributed to the creation of the mambo, a new rhythm and new style that would become a craze in the post-war USA with Pérez Prado’s success5.

Mambo was born out of incorporating more syncopated, African rythms into traditional danzón (violin, horns and timpani) and was first called the “ritmo nuevo6”. This creation was derived, as early as 1937, from a Cuban tumbao rhythm that Cachao played Orestes at the time they played in Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas. Cachao and Orestes’ founding song “Mambo” (a “voodoo priestess” in Haiti) alludes to Afro-Cuban spirituality (santería and lucumí), but it also contains short, obsessive horns (and Orestes Lopez’ cello) riffs, much like those heard in swing era big band jazz7.

In the 1940s, the term descarga (“unload”) was already in use to describe boleros performed in a jazz-influenced way, with some improvisations (Cuban bolero is slow and performed by seductive crooners singing about love). At the end of the decade the very popular romantic Cuban song, the canción, as well as the slow bolero, expanded this wider approach; the trend left more room for soloists and was called feelín or filín. The outstanding trumpet player, El Negro Vivar, was a cornerstone of these jam sessions held at the Tropicana, where he also played regular shows earlier in the night. He can be heard here on many tunes.

The filin’ style was a form of Cuban jazz. It was rooted in the tradition of troubadour poets (the trova) who backed themselves on the guitar. The filin fashion lasted for a few years but withered after the 1959 revolution. With the new “conjunto” type bands and the US influence, Cuban music had entered a new phase.

Panart

Panart (a contraction of “Pan-American Art”), the main and first truly Cuban record company, was founded in 1944 by engineer and musician Ramón S. Sabat (1902-1986). He had studied the clarinet, flute, piano and saxophone in Cuba with José Rivero Rodríguez. In 1919, Sabat left to study music in the USA. He joined the US Army, where he became part of a group of musicians in the military, then worked for several New York record companies before returning to Cuba, where he became a music producer in 1943.

The name of his Areíto studios came from a taíno (Caribbean Native Indian) term describing ritual music and choreographies performed as tributes to leaders, divinities and cemi, the spirits of the ancestors. Those legendary studios were nationalized in 1961, along with the Panart brand, which moved to Miami. The studios are still at #410 Calle San Miguel, in Havana’s historic centre.

The circulation of Cuban records after the war allowed other Caribbean, Spanish-speaking countries to succumb to their influence. Countries such as Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic all avidly took up these new musical styles. Cuban records (danzón, bolero, rumba, son, etc.) also began to circulate in the nearby USA.

Some US jazz musicians then saw in Cuban music a way to re-establish ties with unattainable, original African cultures, of which deep traces could be found in santería and Yoruba lucumí rituals, as well as in rumba and bata percussion8.

For example, Ogueré Mi China here is an invocation to Yoruba Orisha Shango, and Potpurrit de Congas gives a good insight into the intensity of trance-inducing animist rituals. On Mucho Humo, some trumpet, piano and flute is informally improvised, in a free spirit, over traditional rumba percussion. In return, US bands’ style, creativity and professionalism left their mark on Dominican merengue9, Haitian konpa10 and Jamaican jazz11, as well as Havana musicians and many other professional musicians in the Caribbean.

Ramón Sabat’s Panart Records grew steadily. Following the success of Dominican merengue and Pérez Prado’s mambos in the United States, Sabat landed a foreign distribution deal with Decca in 1952. He was in competition with New York-based RCA Victor but remained the main producer on the island. Eventually, his records were distributed abroad by Capitol in Hollywood, as the old-fashioned charanga bands of the past were replaced by new groups, including Conjunto Casino (featuring arranger, composer and tres player Niño Rivera. Two son montuno-influenced tracks by Rivera’s band open disc 3.) By then Sabat had some of the best son montuno artists in his stable. Panart’s son montuno catalogue also included Orquesta Sublime, Conjunto Marquetti, Conjunto Chapottin, Orquesta Novedades, Orquesta Rey Diaz Calvet and Compay Secundo, who would become internationally famous as part of the Buenavista Social Club in 199912. Sabat obtained exclusive rights to professional and ambitious bands such as La Sonora Matancera, Julio Gutiérrez and his Orchestra and Cachao’s team; Cachao also worked with the Philharmonic as well as Orquesta Arcaño y sus Maravillas.

Caribbean in America

In New York, Machito’s group recorded with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and other high-profile jazz musicians. Cuban music was beginning to be accepted in the US because modern jazz giants held it in high esteem, finding it to be a top-level form of African-American music like their own. They also found swing rhythms in it that were common in US jazz.

The first Trinidadian calypso hit records in the US (The Andrews Sisters’ cover of “Rum and Coca-Cola” in 1944, followed by Harry Belafonte’s Jamaican mento triumph of 195613), Pérez Prado’s mambo trend, starting in 1949, Angel Viloria with Doris Valladares’ Dominican merengue fashion as from 1950, then the Cuban cha cha chá’s success, all were the fruits of a Caribbean diaspora recording in New York City.

New York-born Tito Puente played mambo all over Los Angeles and New York. This very rich period is documented in our Caribbean in America 1915-196214, Roots of Mambo 1930-195015 and Cuba in America 1939-196216 sets.

On December 21, 1950, Charlie Parker recorded “Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite” for Norman Granz, a tune composed by Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo, and performed with a 20-piece orchestra conducted by Cuban migrant Chico O’Farrill17. Chico would also work with Dizzy on “Manteca Theme” (May 24, 1954). He specialised in sophisticated orchestrations, which, for instance, influenced Stan Kenton’s famous 1956 Cuba Fire! album, recorded in New York.

Although it was originally released under the name Cuban Jam Sessions and used Afro-Cuban rhythms, Chico O’Farrill’s contribution to this set is perhaps more in the vein of swing-type jazz for big bands, echoing Dizzy Gillespie’s Orchestra of the late Forties, rather than loose improvisation, as displayed here by Cachao or Julio Gutiérrez. But it displays another direction Cuban music would soon branch out into.

Meanwhile, New-Yorker Tito Puente recorded instrumental mambo hits like “Ran Kan Kan” (1955), where long xylophone solos can be heard18. In 1952, New York jazz producer Norman Granz had percussionnist Jack Costanzo (on one side) and Bebo Valdés, heir to the feelin trend (on the other) and more local musicians record a jazz album in Havana. Their Cubano album came out under the name Andre’s All Stars in 1956. This was a significant step in the development of Cuban jazz. Inevitably, the musicians who remained in Cuba dreamt of cashing in on this international trend, which so far had escaped them.

Descarga

Panart exported records to the USA, where interest was growing after the release of jazz/Cuban music fusion recordings by Machito, Chano Pozo, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Chico O’Farrill, Mongo Santamaria, Cal Tjader, Slim Gaillard, Stan Kenton, Tito Puente and now Bebo Valdés and Jack Costanzo.

It was an obvious choice for Ramón Sabat to ask one of his best groups to record a descarga album, a jam session. José Gutiérrez had started conducting the Orquesta Casino de la Playa in 1941 (featuring Perruchín on piano) before he started his own group. He had conducted his own orchestra since 1948. This featured saxophone player Emilio Peñalver, percussionnist Óscar Valdés and trumpet player “El Negro” Vivar, first-class musicians who can be heard shining here. Gutiérrez also backed various artists on television shows.

The José Gutiérrez Orquesta recorded Descarga Caliente, the first ever descarga recording, at Areíto Studio around 1956. After a second studio session (with a small audience) Panart issued an album that same year. The tunes were informal, unedited & sometimes a little long, but the album, which was intended to be a commercial one, obtained unexpectedly good reviews and sold well. As in US clubs, the best Havana musicians got together to play and improvise late at night, in the spirit of jazz, after their paid gigs had finished (the Tropicana Club was a hip spot then for jam sessions in Havana).

In 1956, on top of working in various revues, as well as with Antonio Arcaño’s orchestra, with which he’d introduced the mambo beat some twenty years before, Cachao played in José Fajardo’s orchestra, which would eventually record some descargas, too. In order to improvise and mix styles over a layer of rhythms and chord progressions typical of Cuban music, Cachao met up with his colleagues and musician friends around four in the morning,

The descargas of stylist Cachao borrowed the use of bongos, tres and trumpets from son groups; you could also hear the call-and-response element from the rumba and son montuno, some flute, güiro wood percussion (idiophone) and paila drums borrowed from charanga and danzón, not forgetting, also, the saxophones and trombones found in the new, upcoming Cuban jazz. The very best virtuosos in the country thus invented together this new step of the music. The first and excellent descarga by Cachao y su Combo was recorded at night, after the stage work, as if it was a club jam session, but it was all done at Areíto Studios. It was released in 1957 on Panart under the title Cachao y su Combo, Descarga Cubanas (disc 1, tracks 8-16 & disc 2, tracks 1-3).

In 1961 the album was released in the US as Cachao y su Ritmo, Cuban Jam Sessions in Miniature, because the tracks were much shorter than the usual club improvisations. This was Cachao’s first album released under his own name.

Legendary Cuban musicians can be heard here, including pianist Pedro “Perruchín” Jústiz, who’d learned to play the piano from his mother in a family of musicians. It is in the trova band Los Trovadores del Tono that he met Chombo Silva and encouraged him to take up the saxophone, an instrument Perruchín had had to quit earlier because of asthma. The pianist had worked with Julio Gutiérrez in 1941, before joining Los Swing Boys, where he played with Emilio Peñalver in 1942. By then Chombo Silva had become a saxophone master, but their different jobs did not bring all of these virtuosos together in the same line up.

These prestigious musicians knew each other well and found themselves recording together at last through the magic of a summit meeting in the impromptu, spontaneous spirit of jazz. Perruchín had joined a multitude of top ranking groups, including Beny Moré’s famous grand big band in 1953, but this did not stop him from cutting these improvisations with Julio Gutiérrez and Cachao. Tata Güines, “The King of Congas,” had come from Güines, a poor, small town south of Havana, where he had learnt the rhythms by hitting cardboard boxes. Aged twenty, he was already known as one of the best conga players on the island, a tumbadero. He had played with the greatest musicians. Drummer Walfredo de los Reyes III was the son of a great trumpet player. He backed Julio Gutiérrez during his TV shows on Channel 4; on these recordings he sometimes hit the timbales with one hand and the congas with the other.

Trumpet wizard El Negro Vivar played bop-style jazz as well as Cuban music. He also contributed to Beny Moré’s ‘giant orchestra’ and never missed a late night descarga at the Tropicana Club, where he played in the evening. He can be heard on many of the tracks on this set.

Little information has surfaced about these recordings, which were made during a few late night Havana sessions, at a time when Cuban music was not well documented, if at all. As for some of the other titles included here, many of Cachao’s classics cannot be dated precisely (1957-1959), bearing in mind that Cachao left the country in 1961. This was in the aftermath of the communist revolution — and Panart’s subsequent nationalisation. Musicians’ credits are therefore likely to include some inaccuracies.

Nevertheless, these recording are truly original and they much inspired some big names in US music, including Cal Tjader, Carlos Santana, Tito Puente, Lalo Schifrin, Xavier Cugat and the rise of salsa, which would soon be born in New York.

This box set does justice to these often neglected and sometimes forgotten recordings. The quality and historical importance of experimental New York jazz/Cuban music fusions issued in the USA (Charlie Parker, Machito, Dizzy Gillespie, etc.) ought not be doubted, but the authenticity of the true, pure Cuban jazz heard here at its very best is as irreplaceable as it is unrivalled.

Bruno BLUM, February 2018

© Frémeaux & Associés 2018

Thanks to Chris Carter for proofreading, Crocodisc, Lola Delaire, Franck Jacques, Philippe Lesage and Roger Steffens.

1. Read the booklet and listen to Retrospective des Musiques Cubaines 1981-1997 in this series.

2. Read the booklet and listen to Amour Bananes et Ananas, Anthologie de la Chanson Exotique in this series.

3. Read Olivier Cossard and Helio Orovo’s booklet and listen to Cuba - Bal à La Havane 1926-1937 in this series.

4. Read Isabelle Leymarie’s booklet and listen to Cuba 1923-1995 in this series.

5. Read Pierre Carlu’s booklet and listen to Mambo - Big Bands 1946-1957 in this series.

6. Read Bruno Blum’s booklet and listen to Roots of Funk 1947-1962, which includes several syncopated Cuban recordings, in this series.

7. The original version of the song “Mambo” by Antonio Arcaño y sus Maravillas is available on Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 in this series.

8. Read the booklet & listen to Cuba - Santería, Lucumí, Regla de Ochá, Regla de Ifá, Batá Rituals in this series.

9. Read the booklet and listen to Dominican Republic - Merengue, Haiti, Cuba, Virgin Islands, Bahamas, New York 1949-1962 in this series.

10. Read the booklet and listen to Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 in this series.

11. Read the booklet and listen to Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 in this series.

12. Read the booklet and listen to Cuba - Son Montuno 1944-1962 to be published in this series.

13. Read the booklet and listen to Harry Belafonte - Calypso-Mento-Folk 1954-1957 in this series.

14. Read the booklet and listen to Caribbean in America 1915-1962, which shows the musical encounter of Caribbean and US music, in this series.

15. Read the booklet and listen to Roots of Mambo 1930-1950 in this series.

16. Read the booklet and listen to Cuba in America 1939-1962, which shows the musical encounter of Cuban and US music, in this series.

17. “Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite” by Machito and his Orchestra, featuring Charlie Parker, directed by Chico O’Farrill is available in Volume 9 of The Complete Charlie Parker in this series. More titles featuring these artists are available in Volume 8.

18. The original version of “Ran Kan Kan” is available on Great Black Music Roots 1927-1962 in this series.

CUBA JAZZ

Jam Sessions - Descargas 1956-1961

All tracks produced by Ramón Sabat except where mentioned. Mostly recorded

by Fernando Blanco and Edwin Fernandez De Castro at Panart’s Areíto Studios,

410 de la Calle San Miguel, Central Habana, La Habana, Cuba,

except where mentioned. Original cutting by Fernando Blanco.

Personnel may vary on each track.

Discography - Disc 1

Julio Gutiérrez y Orquesta

Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Edilberto Scrich-as; José Silva aka Chombo, Emilio Peñalver-ts; Osvaldo Urrutia aka Mosquifin-bs; Juan Pablo Miranda-fl; José Antonio Mendez-g; Julio Gutiérrez, Pedro Nolasco Jústiz Rodríguez aka Peruchín-p, direction; Salvador Vivar-b; Walfredo de los Reyes, Jr.-d; Jesus Ezquijarrosa aka Chuchu-timbales; Óscar Valdés-bongos; Marcelino Valdés-congas; vocal chorus. Recorded by Fernando Blanco, Edwin Fernandez De Castro. Album Cuban Jam Session. Recorded in 1956. Panart LD-3055.

1. DESCARGA CALIENTE

(Julio Gutiérrez)

Note: this recording is also known as «Jam Session» and «Cachao te Pone a Bailar.»

2. INTRODUCCION

(Julio Gutiérrez)

3. THEME ON ‘PERFIDIA’

(Alberto Domínguez)

4. THEME ON MAMBO

(Orestes López Valdés)

5. CIMARRÓN

6. OYE MI RITMO CHA CHA CHÁ

(Julio Gutiérrez)

Note: this composition is based on Julio Gutiérrez’ song «Este el Ritmo del Cha Cha Chá.»

7. OPUS FOR DANCING

Cachao y su Combo

Vocalists vary on different tracks and include: Alfredo León, Adelso Paz Rodriguez aka Rolito, Orlando Reyes, Estanislao Laíto Sureda Hernandez aka Laíto Sureda aka Laíto Sr., Pachungo Fernández, Memo Furé, Gerardo Portillo-v; Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Generoso Jiménez aka El Tojo-tb on 9 & 10; Richard Egües-fl; Emilio Peñalver-ts on 12; Virgilio Vixama-bs on 12; Niño Rivera-tres on 13; Orestes López-piano on 10, 14, 15, 16; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-music direction, b, p on 9; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines-congas, b on 9; Guillermo Barreto-timbales; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo-bongos; Gustavo Tamayo-güiro. Album Descargas Cubanas. Panart LD-2092. Recorded in 1957.

8. TROMBÓN CRIOLLO

(Gerard Portillo)

9. CONTROVERSIA DE METALES

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

10. ESTUDIO EN TROMPETA

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

11. GUAJEO DE SAXOS

(Emilio Peñalver)

12. OYE MI TRES MONTUNO

(Andrés Echevarría)

13. MALANGA AMARILLA

(Silvio Contreras)

14. CÓGELE EN GOLPE

(A. Castillo, Jr.)

15. PAMPARANA

(Alfredo León)

16. DESCARGA CUBANA

(Osvaldo Estivill)

Discography - Disc 2

Cachao y su Combo

Same as disc 1, track 11.

1. GOZA MI TRUMPETA

(Osvaldo Estivill)

2. A GOZAR TIMBERO

(Osvaldo Estivill)

Cachao y su Combo

Same as disc 1, track 11. Richard Egües-fl.

3. SORPRESA DE FLAUTA

(Osvaldo Estivill)

Cachao y su Orquesta Cubana

Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro, Armendo Armenteros-tp; Generoso Jiménez Garciá aka Tojo-tb on 9 & 10; Niño Rivera-tres on 13; Orestes López Valdés-piano on 10, 14, 15, 16; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-music direction, b, p on 9; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines or Ricardo Abreu aka Los Papines-congas; Guillermo Barreto-timbales. Radio Progreso Studios, La Habana, Cuba, 1957-1959.

4. OGUERÉ MI CHINA

(unknown)

5. EL MANISERO

(Moisés Simón Rodríguez aka Moisés Simons)

Note: this composition is also known as «The Peanut Vendor.»

6. DESCARGA MAMBO

(unknown)

Cachao y su Combo

Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro, Armendo Armenteros-tp; Generoso Jiménez Garciá aka Tojo-tb; Orestes López Valdés-piano; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-music direction, b; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines; Guillermo Barreto-timbales. 1958-1959. Bonita BON 105 (1959).

7. DESCARGA GUAJIRA

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

8. LA INCONCLUSA

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

Same as disc 2, track 6.

9. REDENCIÓN

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

Same as disc 2, tracks 7&8.

10. LA LUZ

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

Possibly same as disc 1, track 11, with possibly José Antonio Mendez on electric guitar. 1958-1959. Chant Du Monde LDX-S-4249.

11. OLÉ

(Enemelio Jiménez)

12. A GOZAR CON EL COMBO

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

Same as disc 1, track 11.

13. A GOZAR, TIMBERO

(Osvaldo Estivill)

14. PAMPARANA

(Alfredo León)

Walfredo de Los Reyes & his All Star Band:

Luis Escalante-tp; Julio Guerrero-fl; Jesus Caúnedo-as; Paquito Echeverria-p; Luis Rodriguez aka Pellejo, Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-b; Walfredo de Los Reyes-timbales; Ricardo Abreu aka Los Papines-congas. Produced by Rafael Álvarez Guedes, Guillermo Álvarez Guedes aka Álvarez Guedes, Ernesto Duarte Brito. Habana, Cuba, 1957-1959. Gema LPG-1150.

15. ES DIFERENTE

(Oreste López Valdés)

16. MUCHO HUMO

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

Cachao y su Combo

Same as disc 2, track 4, 5 & 6.

17. DESCARGA MEXICANA

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

18. DESCARGA ÑAÑIGA

(unknown)

19. POPURRIT DE CONGAS

(unknown)

Same as disc 2,

track 5.

20. DESCARGA GENERAL

(Israel López Valdés

aka Cachao)

Discography - Disc 3

Niño Rivera’s Cuban All-Stars:

V, chorus; Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Richard Egües-fl; Emilio Peñalver-ts; Andrés Perfecto Eleuterio Goldino Confesor Echevarría Callava aka Niño Rivera-tres, conductor; Orestes López Valdés aka Orestes López aka Macho-p; Salvador Vivar aka Bol Vivar-b; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo aka Yeyito-bongos; Tata Güines-congas; Gustavo Tamayo-guiro; Guillermo Barreto-timbales. 1957.

1. MONTUNO GUAJIRO

(Andrés Perfecto Eleuterio Goldino Confesor Echevarría Callava aka Niño Rivera)

2. CHA CHA CHÃ MONTUNO

(Andrés Perfecto Eleuterio Goldino Confesor Echevarría Callava aka Niño Rivera)

Same as disc 2, tracks 15 & 16.

3. CHA CHA CHÁ DE LOS POLLOS

(Ernesto Antonio Puente, Jr. aka Tito Puente)

4. LAS BOINAS DE CACHAO

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

5. LECHE CON RÓN

(Paquito Echevarría)

Possibly same as disc 2, tracks 4, 5 & 6.

6. EL FANTASMA DEL COMBO

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

7. EL BOMBÍN DE PERUCHO

(Israel López Valdés aka Cachao)

8. JUAN PESCAO

(Isidor Keiser aka Irving Caesar, Vincent Millie Youmans, arranged by Orestes López Valdés)

Note: this composition is also known as «Tea for Two.»

9. AVANCE JUVENIL

(Buenaventura López)

10. LA FLORESTA

(Orestes López Valdés)

Same as disc 2, track 6.

11. RUMBA SABROSA

(Orestes López Valdés)

Fajardo and his All Stars

José Alberto Fajardo Ramos aka José Fajardo-fl; charanga band.

New York, 1957. Panart LP 3102.

12. PA’ COCO SOLO

(José Alberto Fajardo Ramos aka José Fajardo)

Rolando Aguiló y su Estrellas

Rolando Aguiló-tp, direction; as, p, bongos, congas. 1961. Maype 193.

13. EL VIEJO YUMBA

(Rolando Aguilo)

14. DESCARGA

(Isidor Keiser aka Irving Caesar, Vincent Millie Youmans, arranged by Orestes López Valdés)

Note: this composition is also known as «Tea for Two».

15. LA ULTIMA NOCHE

(Roberto Collazo Peña aka Bobby Collazo)

16. DESCARGA CRIOLLA

(Ray Barretto)

Chico O’Farrill y All Star Cubano.

Musicians include: Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Delahoza-tb; Richard Egües-fl; Osvaldo Peñalver-as; Emilio Peñalver-ts; Pedro Justiz aka Peruchín-p; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-b; Walfredo de los Reyes, Sr.-d; Tata Güines-congas; wind instruments orchestra. Arturo O’Farrill aka Chico-arr, direction. 1957.

17. DESCARGA NÚMERO UNO

(Arturo O’Farrill aka Chico O’Farrill)

18. DESCARGA NÚMERO DOS

(Arturo O’Farrill aka Chico O’Farrill)

19. BILONGO

(Guillermo Rodríguez Fiffé)

Enregistrées avant la révolution, au cœur de l’âge d’or de la musique cubaine, les «descargas» originelles déchaînent la puissance spirituelle de la transe répétitive. Elles mélangent improvisations inspirées et chœurs habités, propulsés par des rythmes locaux aux percussions démentes. Cachao et ses amis ont réuni la crème des musiciens de l’île pour graver quelques-uns des sommets de la musique cubaine : les inaltérables classiques fondateurs des « Cuban Jam Sessions » dont Bruno Blum raconte la légende dans un livret de 28 pages. Indispensable à tout amateur de jazz éclairé. Avec Oreste López, Peruchín, Emilio Peñalver, Tata Güines, Chuchu, Tojo, Guillermo Barreto, Chombo Silva, Óscar Valdés, Mosquifin, El Negro Vivar…

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Recorded right before the revolution, at the heart of the golden age of Cuban Music, the original «descargas» unleash the spiritual power of repetitive trance. They blend inspired improvisations, the inner fire of hypnotising choruses propelled by local rhythms and demented percussions. Cachao and his friends brought the cream of the island’s musicians together to cut some of Cuban music’s finest moments: the steadfast, founding “Cuban Jam Sessions” classics. Bruno Blum tells their legend in a 28-page booklet. Indispensable to any enlightened jazz enthusiast. Featuring Oreste López, Peruchín, Emilio Peñalver, Tata Güines, Chuchu, Tojo, Guillermo Barreto, Chombo Silva, Óscar Valdés, Mosquifin, El Negro Vivar…

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Disc 1

Julio Gutiérrez y Orquesta

1. DESCARGA CALIENTE 16’16

2. INTRODUCCION 0’29

3. THEME ON ‘PERFIDIA’ 8’27

4. THEME ON ‘MAMBO’ 3’30

6. OYE MI RITMO CHA CHA CHÁ 6’27

7. OPUS FOR DANCING 4’48

Cachao y su Combo

8. TROMBÓN CRIOLLO 10’18

9. CONTROVERSIA DE METALES 3’00

10. ESTUDIO EN TROMPETA 2’23

11. GUAJEO DE SAXOS 2’25

12. OYE MI TRES MONTUNO 2’42

13. MALANGA AMARILLA 3’15

14. CÓGELE EN GOLPE 2’44

15. PAMPARANA 2’35

16. DESCARGA CUBANA 3’04

Disc 2

Cachao y su Combo

1. GOZA MI TRUMPETA 2’59

2. A GOZAR TIMBERO 3’01

3. SORPRESA DE FLAUTA 2’47

Cachao y su Orquesta Cubana

4. OGUERE MI CHINA 3’22

5. EL MANISERO [The Peanut Vendor] 3’01

6. DESCARGA MAMBO 5’02

Cachao y su Conjunto

7. DESCARGA GUAJIRA 5’49

8. LA INCONCLUSA 3’28

9. REDENCIÓN 3’12

10. LA LUZ 4’40

11. OLÉ 4’33

12. A GOZAR CON EL COMBO 4’26

13. A GOZAR, TIMBERO 3’01

14. PAMPARANA 2’41

Walfredo de los Reyes & his All-Stars

15. ES DIFERENTE 2’49

16. MUCHO HUMO 3’16

Cachao y su Conjunto

17. DESCARGA MEXICANA 4’55

18. DESCARGA ÑAÑIGA 5’12

19. POPURRIT DE CONGAS 5’36

Cachao y su Ritmo Caliente

20. DESCARGA GENERAL 3’38

Disc 3

Niño Rivera’s Cuban All-Stars

1. MONTUNO GUAJIRO 9’22

2. CHA CHA CHÁ MONTUNO 8’51

Walfredo de Los Reyes & his All Star Band

3. CHA CHA CHÁ DE LOS POLLOS 2’45

4. LAS BOINAS DE CACHAO 2’58

5. LECHE CON RÓN 2’55

Cachao y su Conjunto

6. EL FANTASMA DEL COMBO 5’16

7. EL BOMBÍN DE PERUCHO 4’28

8. JUAN PESCAO [Tea for Two] 2’51

9. AVANCE JUVENIL 3’15

10. LA FLORESTA 2’42

11. RUMBA SABROSA 5’03

Fajardo and his All Stars

12. PA’ COCO SOLO 3’53

Rolando Aguiló y su Estrellas

13. EL VIEJO YUMBA 2’30

14. DESCARGA [Tea for Two] 3’33

15. LA ULTIMA NOCHE 3’16

16. DESCARGA CRIOLLA 3’28

Chico O’Farrill y All Star Cubano

17. DESCARGA NÚMERO UNO 2’57

18. DESCARGA NÚMERO DOS 2’51

19. BILONGO 2’55