- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

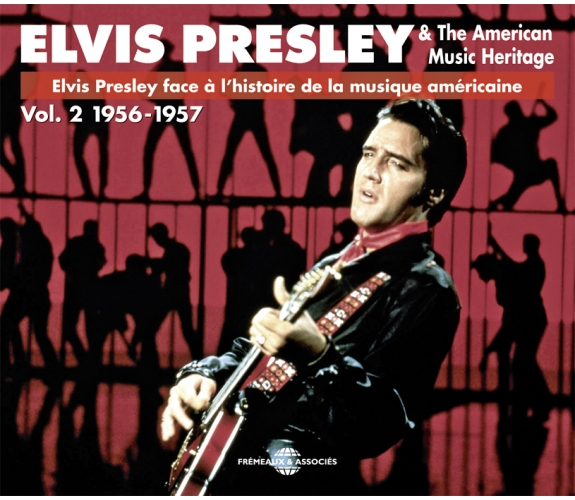

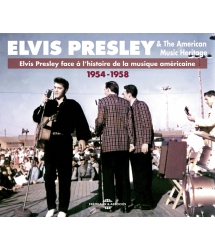

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE VOL.2

ELVIS PRESLEY

Ref.: FA5383

EAN : 3561302538327

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 52 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE VOL.2

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE VOL.2

This second volume continues the story of rock ‘n’ roll’s most popular icon in 1956. To smooth his “subversive” image in a conservative America, Elvis Presley turned to other kinds of music and began recording gospel, country music – even Christmas songs – with brio and authenticity. In parallel, he also had his greatest rock hits: All Shook Up, Teddy Bear and Jailhouse Rock. For this set, Bruno Blum has compiled recordings Elvis made in 1956-57, alternated with the original versions of these pieces. The comparison provides a perspective allowing listeners to better understand Presley’s immense contribution to the legend of an America set to conquer the world. P. FRÉMEAUX

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE...

EDDY MITCHELL, JOHNNY HALLYDAY, DICK RIVERS…

JAMES BROWN

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Long Tall SallyLittle RichardRichard Penniman00:02:111956

-

2Long Tall SallyElvis PresleyRichard Penniman00:01:561956

-

3Old ShepRed FoleyRed Foley00:02:521941

-

4Old ShepElvis PresleyRed Foley00:04:191941

-

5Too MuchBernard HardisonBernard Weinmann00:02:241955

-

6Too MuchElvis PresleyBernard Weinmann00:02:341956

-

7Any Place Is ParadiseElvis PresleyJoe Thomas00:02:311955

-

8Reddy TeddyLittle RichardJohn Marascalco00:02:121956

-

9Redy TeddyElvis PresleyJohn Marascalco00:02:001956

-

10First In LineElvis PresleyAaron Schroeder00:03:251956

-

11Rip It UpLittle RichardJohn Marascalco00:02:241956

-

12Rip It UpElvis PresleyRobert Blackwell00:01:561956

-

13I BelieveJane FromanErvin Drake00:03:181952

-

14I BelieveElvis PresleyErvin Drake00:02:061957

-

15Tell Me WhyMarie KnightTitus Turner00:02:131956

-

16Tell Me WhyElvis PresleyTitus Turner00:02:081956

-

17Got A Lot O' Livin' To Do!Elvis PresleyAaron Schroeder00:02:341956

-

18I'M All Shook UpDavid HillOtis Blackwell00:02:131956

-

19All Shook UpElvis PresleyOtis Blackwell00:01:591956

-

20Mean Woman BluesElvis PresleyClaude Demetrius00:02:171956

-

21Peace In The ValleyRed FoleyThomas A. Dorsey00:03:131951

-

22Peace In The ValleyElvis PresleyThomas A. Dorsey00:03:211951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1That's When Your Heartaches BeginThe Ink SpotsFred Fisher00:03:171941

-

2That's When Your Heartaches BeginElvis PresleyFred Fisher00:03:241941

-

3Take My Hand Precious LordMahalia JacksonThomas A. Dorsey00:04:141956

-

4Take My Hand Precious LordElvis PresleyThomas A. Dorsey00:03:191956

-

5It Is No SecretStuart HamblenStuart Carl Hamblen00:02:481950

-

6It Is No SecretElvis PresleyStuart Carl Hamblen00:03:561950

-

7Blueberry HillGene AutryAlfred Lewis00:02:401940

-

8Blueberry HillSteve GibsonAlfred Lewis00:02:401949

-

9Blueberry HillFats DominoAlfred Lewis00:02:251957

-

10Blueberry HillElvis PresleyAlfred Lewis00:02:411957

-

11Have I Told You Lately That I Love YouElvis PresleyScott Greene Wiseman00:02:341945

-

12Is It So StrangeElvis PresleyFaron Young00:02:341945

-

13Have I Told You Lately That I Love YouLulu Belle & ScottyScott Greene Wiseman00:02:311945

-

14Let's Have A PartyElvis PresleyJessie Mae Robinson00:01:291957

-

15Lonesome CowboyElvis PresleyRoy Bennett00:03:031957

-

16Hot DogElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:01:151957

-

17Just Let Me Be Your Teddy BearElvis PresleyKal Mann00:01:481957

-

18One Night Of SinSmiley LewisLewis Smiley00:02:181956

-

19One Night Of SinElvis PresleyLewis Smiley00:02:381956

-

20True LoveBing CrosbyCole Porter00:03:071956

-

21True LoveElvis PresleyCole Porter00:02:081957

-

22Loving YouElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:02:131957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Jailhouse RockElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:02:301957

-

2I Need You SoIvory Joe HunterJoe Hunter Ivory00:03:211951

-

3I Need You SoElvis PresleyJoe Hunter Ivory00:02:401951

-

4Young And BeautifulElvis PresleyAaron Schroeder00:02:041951

-

5I Want To Be FreeElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:02:141951

-

6You're So Square Baby I Don't CareElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:01:541951

-

7Don't Leave Me NowElvis PresleyAaron Schroeder00:02:071951

-

8Blue ChristmasErnest TubbBilly Hayes00:02:481949

-

9Blue ChristmasElvis PresleyBilly Hayes00:02:091957

-

10White ChristmasThe DriftersIrving Berlin00:02:401954

-

11White ChristmasMahalia JacksonIrving Berlin00:03:351955

-

12White ChristmasElvis PresleyIrving Berlin00:02:251955

-

13Here Comes Santa ClausGene AutryGene Autry00:02:341953

-

14Here Comes Santa ClausElvis PresleyGene Autry00:01:571953

-

15Silent NightMahalia JacksonJoseph Mohr00:04:281955

-

16Silent NightElvis PresleyJoseph Mohr00:02:251955

-

17O Little Town BethlehemMahalia JacksonPhillips Brooks00:03:471955

-

18O Little Town BethlehemElvis PresleyPhillips Brooks00:02:371955

-

19Santa Bring My Baby BackElvis PresleyAaron Schroeder00:01:541955

-

20Santa Claus Is Back In TownElvis PresleyJerry Leiber00:02:251955

-

21I 'll Be Home For ChristmasBing CrosbyBuck Ram00:02:561943

-

22I 'll Be Home For ChristmasElvis PresleyBuck Ram00:01:541943

Elvis Presley & The American music heritage FA5383

Elvis Presley & the american music heritage

Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine

Vol. 2 1956-1957

Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine

Les critiques jugent les œuvres et ne savent pas qu’ils sont jugés par elles.

Jean Cocteau

On entend toujours la même chanson : après ses premiers succès rock, Elvis Presley a fait de la guimauve. Son départ à l’armée, sa carrière d’acteur, un imprésario cupide, tout est bon pour accuser le jeune chanteur d’une trahison à la bonne cause du rock. Dont Elvis était le roi. Mais que s’est-il vraiment passé ? Qui a vraiment écouté les disques incriminés ? Quelles étaient ses inspirations, ses sources musicales pendant cette deuxième période qui s’affirmait ? Elvis a-t-il véritablement abandonné ceux qui voyaient en lui le chanteur emblématique de la génération du rock and roll, la résurrection de l’idole James Dean, le rebelle sans cause ? En un mot, Elvis a-t-il retourné sa veste ?

On est d’autant plus fondé à se poser cette question si l’on comprend qu’en 1956 le « rock ‘n’ roll » semblait voué à disparaître comme une mode de passage entre mambo, calypso et bientôt bossa nova. De l’avis général, une vague aussi dérangeante, ça ne durerait pas. Nul n’aurait pu prédire que le rock deviendrait un mode d’expression central pour les adolescents - et ce pour longtemps.

Le triomphe

L’abjecte Deuxième Guerre Mondiale enfin enterrée - et la guerre de Corée terminée depuis l’été 1953 - une nouvelle génération surgissait, avide de liberté et de bons moments. Mais huit ans avant le début de la Beatlemania, qui pouvait se douter de l’importance qu’allait prendre le genre musical rock ? Qui pouvait imaginer à quel point la culture rock, par essence marginale, affirmation générationnelle, identitaire et le cliché de « l’attitude rock » seraient chargés d’affect par la jeunesse des décennies à venir ? Avec le recul, on comprend bien que l’attitude adoptée par Elvis Presley au faîte de la gloire porte encore une énorme valeur symbolique. Pour la jeunesse américaine de l’époque, ses choix de carrière avaient une importance plus grande encore.

Le succès de Frank Sinatra au début des années 1940 avait été analogue, mais à l’âge d’or d’Hollywood, il avait dû attendre que le cinéma lui apporte la consécration. Il n’avait pas pu bénéficier des médias audiovisuels de masse (on n’en était qu’aux débuts de la radio et la télévision était presque inexistante), ce qui a réduit son impact initial. Et si ses concerts déclenchaient des débordements importants chez les jeunes bobbysoxers, la musique et la chorégraphie d’Ol’ Blue Eyes en action étaient loin de colporter l’excitation propagée comme une trainée de poudre par le rock and roll - c’est le moins qu’on puisse dire. En revanche, les concerts d’Elvis et ses danses spontanées provoquaient dès la première seconde des scènes d’absolue hystérie collective. Très vite, les hurlements continuels des adolescentes perdant le contrôle d’elles-mêmes couvraient totalement le son des musiciens, qui n’entendaient même plus la puissante batterie sur scène. La télévision, une invention nouvelle, relayait soudain cet impact inouï au cœur d’une Amérique conservatrice qui n’aimait pas être bousculée. Arrivé sans crier gare au sommet d’une fulgurante success story sans précédent dans l’histoire des États-Unis, ses ventes de disques, ses prestations télévisées comme son premier film « Love Me Tender » en 1956 ont battu tous les records, séduit tous les publics, jeune, moins jeune, noir, blanc, latino, du sud, du nord, d’Amérique et d’ailleurs. Elvis était prodigieux. Les listes de vente de disques pop (variété), country & western (Blancs) et même R&B (Noirs à part, ségrégation oblige) étaient prises d’assaut par des morceaux comme « Hound Dog », All Shook Up (dont la version de David Hill incluse ici est sortie quelques semaines avant celle d’Elvis) ou (Just Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear. Elvis l’insomniaque et son équipe sillonnaient les États-Unis en avion, en train, en Cadillac, courbant devant un agenda serré.

Moins de deux ans plutôt, Elvis Presley n’avait littéralement jamais voyagé. Sa famille avait connu une pauvreté accablante, quittant fin 1948 la misère de Tupelo en espérant trouver une vie meilleure à Memphis, vivant longtemps à trois dans une seule pièce avant de décrocher un logement social. Passionné par la musique, après avoir été engagé par quelques entreprises comme travailleur manuel, le jeune Elvis conduisait un camion pour un salaire dérisoire quand il a sorti son premier disque - un premier chef-d’œuvre1. Sidéré par ce qu’il lui arrivait, il n’a cessé de répéter qu’il attribuait son démentiel triomphe à un coup de chance, une intervention divine qui lui avait permis d’acheter une grande maison à sa famille et de posséder plusieurs Cadillac. Pas du tout préparé à une telle gloire, ce jeune autodidacte de vingt-et-un ans avait tous les projecteurs braqués sur lui et subissait une pression considérable.

Le retour de flamme

À la gestion difficile de ses affaires, assurée depuis le début 1955 par son brillant et dévoué imprésario, le grossier et impitoyable « Colonel » Tom Parker, s’ajoutaient de plus en plus de critiques injustes, acerbes et malveillantes. Il faut bien comprendre que la variété de Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin ou Bing Crosby, des chanteurs populaires devenus vedettes de cinéma, menaçaient bien peu l’ordre établi, tout du moins dans leurs représentations publiques et cinématographiques. Même dans un film sulfureux comme le remarquable « L’Homme au bras d’or » (Otto Preminger, 1955) où le talentueux Sinatra incarne un batteur de jazz héroïnomane, la morale est sauve comme dans autant de happy ends hollywoodiens. Des chanteurs blancs du sud des États-Unis avaient eux aussi connu de grands succès, parmi lesquels Hank Williams, Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, Stuart Hamblen, Hank Snow ou Eddy Arnold (trois fois numéro un des ventes en 1947, Arnold avait eu comme imprésario Tom Parker, qui devint ensuite celui de Hank Snow puis de Presley). Mais bien que doué et travailleur, Elvis était bien plus qu’un chanteur, il était un impensable phénomène. Et à ce titre, ses moindres faits et gestes étaient scrutés. Comme on l’a vu dans le premier volume de cette série consacré aux trois premières années de sa carrière, dans un effarant contexte de stricte ségrégation raciale il ne faisait pas l’unanimité, notamment pour la connotation afro-américaine contenue dans sa musique et sa danse. Dans le même temps le 17 mai 1954, la Cour Suprême des États-Unis avait établi que la ségrégation raciale dans les écoles était anticonstitutionnelle et le président Eisenhower ordonna la déségrégation dans l’enseignement. Rappelons le contexte : en 1957, refusant d’obéir, le populaire gouverneur de l’Arkansas Orval Faubus envoya la garde nationale de son état pour empêcher les enfants noirs d’accéder aux écoles de Little Rock (à quelques kilomètres de Memphis, où résidaient les Presley) ! Eisenhower retira le commandement des gardes nationaux à Faubus et envoya l’armée pour qu’elle ouvre l’accès aux écoles.

Plébiscité par la jeunesse, Elvis Presley a rarement laissé la génération des parents indifférente. Certains l’appréciaient, d’autres plus conservateurs maudissaient ce trublion. Des réactions extrêmement négatives se sont multipliées en 1956. Quelle était la nature de ces critiques ? En lisant la remarquable somme biographique de Peter Guralnick2, on peut réaliser pleinement qu’à l’été 1956, « Jamais encore Elvis n’avait eu à affronter une vague d’attaques personnelles et d’accusations d’outrage à la morale d’une telle ampleur. “Mr. Presley n’a aucun talent pour le chant, ça crève les yeux », déclara Jack Gould dans le modéré New York Times. “La vue du jeune Mr. Presley miaulant ses paroles inintelligibles d’une voix inepte, s’exhibant sur scène à grand renfort de mouvements primitifs, difficiles à décrire en termes acceptables pour un journal lu par toute la famille, a causé une réaction d’une violence inouïe, du jamais vu depuis l’âge de pierre de la télévision, où les décolletés de Dagmar ou de Faysie plongeait vertigineusement” écrivit Jack O’Brian dans le New York Journal-American. [La musique populaire] touche le fond du fond avec les “ahanements et déhanchements obscènes d’un Elvis Presley”, fulminait Ben Gross dans le Daily News. » Le quotidien ajoutait “Les télespectateurs ont eu droit à un échantillon odieux dans l’émission de Milton Berle l’autre soir. Elvis, le rouleur de pelvis, a été déplorable sur le plan musical. En plus, il a offert un spectacle suggestif et vulgaire, teinté d’une bestialité qui devrait être confinée aux bouges et aux bordels. Ce qui m’effare le plus, c’est que Berle et NBC-TV aient pu autoriser cette insulte.” Et sous le titre “Attention Elvis Presley”, l’hebdomadaire catholique America suggéra que : “si les activités de Presley pouvaient se limiter à l’enregistrement de disques, l’homme de spectacle qu’il est n’exercerait peut-être pas une trop mauvaise influence sur la jeunesse, mais le malheur, c’est qu’il se produise en public.”

D’autres déclarations le diabolisant, et en particulier celles de responsables religieux, blessèrent profondément Elvis, très croyant, qui avait en bonne partie appris à chanter et jouer de la guitare à l’église Assembly of God de Tupelo. La polémique s’exportait aussi outre-atlantique. Dans une revue de presse de ses fameuses chroniques de jazz3, Boris Vian lui-même se laissait aller à citer un magazine de jazz anglais très hostile au rock (qui, ironie du sort, deviendrait quelques années plus tard le plus grand hebdomadaire rock britannique) : « Une très jolie apostrophe de Steve Race dans le Melody Maker du 20 octobre 1956, à propos d’Elvis Presley et du Rock and Roll : “Je crains pour l’avenir d’une industrie musicale qui s’abaisse jusqu’à satisfaire la demande d’un groupe juvénile dément, au détriment de la masse de ceux qui veulent encore écouter des chansons chantées sans fausses notes et proprement.” Steve Race a tort de craindre pour l’industrie ; pour la musique, ça, en ce qui concerne Presley, il a pas tort. Mais l’industrie et la musique, ça fait souvent deux. »

Le cornettiste de jazz Boris Vian, qui méprisait plutôt le rock, savait de quoi il parlait : il venait d’écrire les premiers rocks francophones de l’histoire pour Henri Salvador (« Rock and roll mops ») et Magali Noël, qui fit de l’excellent “Fais-moi mal, Johnny” un joli succès. Un peu partout, Elvis Presley était calomnié et moqué. Pourtant, en écoutant ici ses interprétations de mélodies difficiles comme I Need You So ou O Little Town of Bethlehem, on peut difficilement l’accuser de chanter faux.

En réalité, plusieurs éléments choquaient principalement l’Amérique : d’abord la sensualité qui se dégageait des mouvements d’Elvis était inconvenante pour une Amérique extrêmement puritaine et religieuse, peu habituée à ce que des images suggestives surgissent sur l’écran du salon. L’excitation et le vertige provoqués par le rock and roll faisaient complètement oublier ses mérites « musicaux ». Rappelons le contexte de plomb de l’époque : avant la libération sexuelle des années 1960, les femmes américaines négociaient leur virginité contre le mariage. Une jeune femme ne se laissait pas toucher et embrasser en privé était le summum du flirt. Dans le sud très conservateur, rares étaient celles qui dérogeaient à la règle. Séducteur désiré par des dizaines de millions de femmes, en 1954-1957 Elvis a connu des flirts durables avec plusieurs prétendantes, parmi lesquelles Dixie Locke avant le succès, puis June Juanico, Dottie Harmony et l’actrice Natalie Wood qui avait donné la réplique à James Dean dans le film culte La Fureur de Vivre (Nicholas Ray, 1955) ou encore Yvonne Lime. Mais toutes faisaient chambre à part et aucune n’a eu de relation sexuelle avec le chanteur. De toute façon, son manager s’insurgeait contre tout ce qui pouvait se mettre en travers de sa carrière, qui était le sacro-saint objectif numéro un. Le mariage lui était strictement interdit. Tom Parker adressait à peine la parole à ces jeunes femmes. Par le témoignage de ses musiciens, on sait néanmoins qu’Elvis a tout de même passé quelques nuits avec des rencontres sans lendemain. On sait aussi qu’il lui est arrivé d’être présent à des projections de films érotiques organisées par ses amis, mais ces incartades à la bonne morale ne sauront faire oublier la cruelle réalité de ce symbole sexuel : puritanisme, frustration, refoulement, groupies très occasionnelles, masturbation, chagrins d’amour pour plusieurs femmes et hypocrisie ambiante pour tout le monde.

Ensuite, comme il est expliqué en détail dans le premier volume de cette série, le rock and roll était fondamentalement une musique afro-américaine. Presley et son équipe l’ont interprété en y ajoutant une couleur country (avec en particulier la guitare électrique de Scotty Moore et un répertoire partiellement country) qui donna naissance au nouveau genre rockabilly.

Elvis parvint à chanter deux chansons dans le haut-lieu de la musique country, le Grand Ole Opry, qui accepta d’inviter Elvis pour rendre service à son premier producteur, Sam Phillips. Mais comme pour une grande partie du public, la direction conservatrice du Grand Ole Opry pensait que le style d’Elvis était étranger à la culture country et il ne fut pas réinvité - en dépit de son triomphe. Si l’icone du bluegrass Bill Monroe y a très tôt salué le talent d’Elvis (enregistrant son propre « Blue Moon of Kentucky » dans le nouveau style rockabilly à son tour, ce qui a stupéfié le milieu country & western), pour une part importante de la population la musique de Presley était avant tout un signe d’intégration des Afro-américains - une menace de plus à la domination blanche en place au moment où le mouvement de Martin Luther King prenait son essor et faisait les titres des journaux. Chez Elvis dans le Tennessee, patrie du Ku Klux Klan, c’était particulièrement sensible. Rien n’était formulé, publié, mais on n’en pensait pas moins. Comme l’avait fait le New York Journal-American, on préférait parler par métaphores, de « mouvements primitifs », de « bestialité » ou d’« insulte » et tout le monde comprenait le sous-entendu. Quand le 7 décembre 1956 Elvis fit une apparition amicale à un concert caritatif afro-américain et se fit prendre en photo avec B.B. King, grande vedette du blues de cette période, lui aussi résident à Memphis, le message était à la limite de la provocation : en pleine ségrégation raciale, Elvis Presley était ouvertement l’ami des Afro-américains. La presse afro saluera cet engagement et sa reconnaissance de dette musicale à la communauté noire, où beaucoup considéraient Elvis comme une sorte de héros populaire. Le journal afro-américain Memphis World publiera six mois plus tard : « Elvis avait bravé les lois ségrégationnistes de Memphis […] pendant ce qu’on appelle “la soirée pour gens de couleur”. » Quelques journalistes afro-américains n’appréciaient pas ses emprunts au répertoire du rhythm and blues qu’il exploitait et surtout, ils étaient jaloux de la séduction qu’Elvis exerçait sur les adolescentes noires. Mais cette attraction dérangeait surtout une grande partie des classes moyennes blanches d’un certain âge, pour qui les relations amoureuses interraciales étaient inconcevables.

Après « Tutti Frutti » sur son premier album, le deuxième 30cm « Elvis » paru en octobre 1956 contenait pas moins de trois autres reprises de Little Richard (incluses ici), le plus sauvage et le plus éclatant des rockers - noir lui aussi. Au début Little Richard était éclipsé par Elvis, qui a participé à faire connaître son « Tutti Frutti », mais Little Richard s’envola vite de ses propres ailes pour pilonner les amateurs de rock à coups de bombes aussi irrésistibles4 qu’insurpassables. Elvis s’est largement servi dans son fantastique répertoire (quatre morceaux). L’irréparable était commis : dans le sillage d’Elvis des rockers noirs surgissaient dans les circuits de vente jusque-là monopolisés par des artistes blancs (seul le sage Fats Domino avait eu ce privilège auparavant). En outre, le rock menaçait donc bel et bien l’industrie du disque établie avec de nouveaux critères musicaux et une ouverture raciale inédite. En 1955-1957 Bo Diddley plaçait plusieurs succès d’une grande originalité dans son escarcelle5, Chuck Berry accumulait les succès et touchait largement le public blanc. Elvis reprenait son Maybellene sur scène et appréciait particulièrement son Brown Eyed Handsome Man, un plaidoyer pour la justice à l’égard des « hommes aux yeux marrons ». De son côté, le rock blanc naissant commençait à s’organiser. À Memphis, Sam Phillips endetté avait dû revendre le contrat d’Elvis Presley à RCA pour quelques milliers de dollars. Il essayait de se refaire en lançant d’autres jeunes artistes de rockabilly avec sa marque indépendante Sun : Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis et bientôt Roy Orbison, qui alignèrent tous de gros succès. À Hollywood, les disques Capitol répondaient au succès d’Elvis chez RCA avec un nouvel artiste blanc de grand talent, au guitariste éblouissant (Cliff Gallup) : Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps6 lancés par leur irrésistible « Be-Bop-a-Lula » en 1956. Beaucoup pensaient que ce morceau était chanté par Elvis et quand Gene Vincent rencontra celui-ci il s’empressa de s’en excuser. Toujours à Hollywood, les films sur le rock se succédaient : après Graine de violence (Blackboard Jungle, Richard Brooks, 1955) qui avait fait connaître Bill Haley, c’était Rock Rock Rock avec le fameux présentateur Alan Freed, The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956) et d’autres films encore - parmi lesquels les débuts d’Elvis à l’écran dans Love Me Tender (Robert D. Webb, 21 novembre 1956).

À l’été 1956, les critiques sont devenues incessantes, insultantes et malgré son succès immense, le second rôle d’Elvis dans le film Love Me Tender était moqué. S’ajouta alors le « scandale des pots-de-vin » ; des auteurs-compositeurs cédaient des parts de leurs droits d’auteur aux éditeurs de musique en échange d’un accès aux radios, à la télévision (une pratique qui ne se limitait pas au rock and roll) et surtout aux interprètes connus, parmi lesquels Elvis. En décembre 1957, Boris Vian écrira :

« Dans le Melody Maker du 2 novembre, on découvre avec intérêt un aspect réjouissant d’Elvis Presley […]. Voici ce que déclare, jovial, ce cynique personnage (c’est un compliment en l’espèce : cette franchise mérite qu’on l’apprécie ) :

« J’ai fait plus d’un million de dollars cette année - dit-il à Howard Lucraft, son interviewer - mais je ne suis pas musicien du tout. Je ne sais pas jouer de guitare et je n’ai jamais écrit une chanson de ma vie. Pourtant, je signe celles que j’interprète et je touche le tiers des droits sur toutes les chansons que je chante.

Et il ajoute avec un sourire railleur : “Ça serait vraiment idiot, dans ces conditions, d’étudier la musique…”

Ça se passe en Amérique, bien sûr… mais ça arrive quelquefois en France. Le malheur, en France, c’est que certains artistes signent la musique et l’écrivent, parce qu’ils sont honnêtes… mais ils ne savent pas plus l’écrire que Presley.

Alors, que faire ? Écouter Sinatra7. »

Cette critique n’était pas exacte : Elvis continua effectivement, par un arrangement courant à cette époque mis en place par Tom Parker, à s’attribuer une partie des droits d’auteur de quelques-unes des chansons qu’il interpréta, notamment celles d’Otis Blackwell (qui incidemment, était noir). Mais il cessa de le faire fin 1956. Attaque à peine déguisée contre cette musique d’intégration raciale en plein mouvement pour les droits civiques (mouvement lancé par le refus de Rosa Parks de laisser sa place dans le bus à un Blanc le 1er décembre 1955), le scandale des « payola » a fait grand bruit, nuisant considérablement au rock and roll. En 1959, il brisera finalement la carrière d’Alan Freed, DJ emblématique du rock, présentateur de télé non-conformiste qui avait popularisé l’expression « rock and roll » dès 1951 et avait toujours soutenu les artistes afro-américains. Freed avait commencé à avoir des ennuis après une plainte des associés de la chaîne ABC au sud du pays, qui n’avaient pas apprécié de voir le chanteur adolescent Frankie Lymon danser avec une jeune blanche lors d’une émission de télévision de Freed. D’autres DJ associés au rock, comme Dick Clark, auraient des ennuis du même acabit en 1959. Sombrant dans l’alcoolisme, Alan Freed payera de sa vie la dépression qui succéda à sa vie brisée. Les forces réactionnaires de l’Amérique étaient entrées en scène. On ne bouleversait pas impunément la juteuse industrie du disque (écouter ici l’ambiance de la variété d’époque sur I Believe par Jane Froman ou la version originale de It Is No Secret, énorme tube gospel blanc de Stuart Hamblen) avec une musique « primitive ». Le It Is No Secret (What God Can Do) d’Hamblen où Dieu « peut faire pour toi ce qu’il a fait pour d’autres » était pourtant pour Elvis une manière « autobiographique » et sincère de remercier le ciel pour son succès.

Mais alors que le modéré Elvis déclarait publiquement son soutien au candidat de gauche Adlai Stevenson (contre Dwight Eisenhower, président Républicain réélu en 1956), pour une bonne partie de l’Amérique le rock and roll était maintenant la musique du diable. Subissant des pressions que l’on a peine à imaginer, Little Richard déclara forfait et entra en religion en octobre 1957, abandonnant du jour au lendemain sa fabuleuse carrière de chanteur de rock après une série de chefs-d’œuvre. Comme Elvis, il allait lui aussi enregistrer du gospel. Bo Diddley était boycotté par les télévisions à la suite de pressions d’Ed Sullivan avec qui il s’était fâché pour un malentendu où le racisme avait joué son rôle. Chuck Berry serait emprisonné pour détournement de mineure (une Blanche) en 1962. Jerry Lee Lewis traversa un scandale de même nature en mai 1958 (mariage avec une mineure de treize ans, une pratique assez répandue dans le Sud), disparaissant brusquement de la scène. The Big Bopper, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran allaient perdre la vie dans des accidents jamais expliqués. Gravement blessé dans le drame qui tua son ami Cochran en 1960 et sans succès malgré des disques extraordinaires, Gene Vincent verrait lui aussi sa carrière brisée net.

En 1956 après un nuage rose sur fond de tensions raciales, le rock était déjà devenu le paratonnerre utilisé pour stigmatiser toute la nouvelle génération. Elvis ne supportait pas qu’on le critique « sans le connaître ». Le comble était en effet que, contrairement à l’image de sauvage vulgaire et dévergondé que certains médias donnaient de lui avec condescendance, le jeune homme était d’une grande innocence, d’une parfaite sincérité, d’une infinie gentillesse et d’une politesse maladive. Manquant de maturité, couvé par sa mère et son manager, bien élevé, très pieux, d’une humilité proverbiale, il s’efforçait de “faire de son mieux” dans ce maelström où, à son grand dam, il faisait figure de rebelle.

Il était tellement poli et voulait si bien faire qu’il accepta même de chanter « Hound Dog » pour la télévision habillé en queue-de-pie face à un chien, sans danser, ce qui le ridiculisa. Ses fans protestèrent massivement. C’en était trop. Elvis Presley devait faire face et réagir à la mesure des coups qu’on lui portait. Son succès incroyable semblait inaltérable quoi qu’il fasse, mais pour le Colonel, le temps était venu de passer à autre chose.

Gospel

La mode se démode, le style jamais.

Coco Chanel

Dès le début 1956, l’imprésario projetait très logiquement de porter le mythe naissant d’Elvis à l’écran. Après un bout d’essai il signa des contrats juteux pour plusieurs films. Le succès énorme du long métrage Love Me Tender à l’été l’a encouragé à persévérer dans cette voie qui donnera bientôt le meilleur film d’Elvis Presley, Jailhouse Rock (Richard Thorpe, 1957). Elvis était ravi de cette nouvelle direction. Il avait une confiance aveugle en son manager dominateur de vingt-cinq ans plus âgé que lui, qui menait sa carrière avec flair - et une poigne de fer. Le « colonel » Parker a aussi incité son poulain à diversifier son répertoire. Elvis ne demandait pas mieux : il avait déjà largement fait ses preuves en tant que chanteur de rock. Après tout, n’était-ce pas une idée de son premier producteur, Sam Phillips, que de l’encourager à chanter du rock ? Elvis avait déclaré plusieurs fois que tant que la formule fonctionnerait il aurait tort de s’en priver mais maintenant, qui pourrait le blâmer de s’ouvrir aussi à autre chose ? Il n’avait jamais caché son intention de réussir en tant que chanteur de country and western, de ballades, de chansons populaires : plus encore qu’un ronflant « roi du rock », Elvis Presley avait au fond une vocation de talentueux chanteur populaire. Et plus que tout, il souhaitait enregistrer du gospel, la première musique qu’il avait chantée, enfant, à l’Assembly of God de Tupelo. La religion avait beaucoup contribué à structurer la communauté noire. Les negro spirituals et le gospel étaient bien sûr interprétés avec ferveur dans les camp meetings revivalistes, les églises et temples afro-américains. Elvis aimait se promener dans les premières rues du quartier noir de Memphis où la puissance spirituelle émanait des innombrables lieux de cultes chrétiens8 et revivalistes9 où les fidèles afro-américains entraient immanquablement en transes pendant les cantiques - un spectacle difficile à imaginer quand on n’y a pas assisté. Mais le jeune Elvis avait surtout grandi au son des chants de l’Assembly of God, une église blanche où le style de gospel était différent, certainement moins exubérant mais où, à l’exemple de Jack Hess qu’il admirait, le gamin avait été en contact avec la foi et la musique spirituelle. L’Assembly of God avait pratiqué une certaine mixité raciale jusqu’à ce que celle-ci soit interdite par une loi « Jim Crow » ségrégationniste dans les années 1920 et Elvis ne manquait pas une occasion de chanter le gospel, terrain privilégié du rapprochement racial. C’est ce qu’il fit au sein de l’étonnant « Million Dollar Quartet » avec Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins et Johnny Cash enregistré informellement au studio Sun en décembre 1956, mais aussi avec James Brown quand il le rencontra. Le mode de vie très sage du jeune homme, qui détestait l’alcool et le tabac (on ne consommait ni l’un ni l’autre chez lui), comprenait l’écoute de disques de gospel des Clara Ward Singers, de Sister Rosetta Tharpe10, de Mahalia Jackson qui en 1956 était devenue la reine du genre, une célébrité internationale. Elvis était forcément marqué par l’éblouissant gospel noir, mais il appréciait naturellement les groupes vocaux du gospel blanc comme les Blackwood Brothers ou le Statesmen Quartet avec ses grandes influences Jake Hess et « Big Chief » Wetherington, dont il imita le jeu de jambes qui choquait tant les ecclésiastiques. Il choisit d’ailleurs lui-même les Jordanaires, un groupe d’harmonies vocales de Southern Gospel de renom, pour l’accompagner en studio et sur scène dès janvier 1956. Les Jordanaires comptaient parmi les premiers groupes blancs professionnels du gospel à chanter des negro spirituals et comme Elvis, à intégrer l’influence du gospel noir. Le chanteur imposa que leur nom prestigieux figure au côté du sien sur ses disques à une époque où les accompagnateurs n’étaient jamais crédités.

Rien d’étonnant donc à ce que la jeune star accepte une proposition de son éditeur (qui détenait une part des droits de plusieurs célèbres compositions du genre, notamment du grand compositeur du gospel moderne, Thomas A. Dorsey) d’enregistrer des cantiques et chants de noël. Comme toujours, Elvis a puisé dans un répertoire de chansons qui avaient déjà fait leurs preuves, comme I Need You So d’Ivory Joe Hunter, classée au numéro un des ventes R&B en 1950. Comme le précédent volume, cet album présente en regard des interprétations d’Elvis les versions enregistrées des compositions qui l’ont inspiré ; Cependant dans le cas de morceaux comme White Christmas (un des plus gros succès de Bing Crosby) ou le classique Silent Night, composé au XIXe siècle et dont il existe d’innombrables versions, il est difficile d’établir la source qui à coup sûr inspira l’artiste. Pour Peace in the Valley par exemple, Presley chantait depuis l’adolescence ce classique déjà repris par le chanteur de country Red Foley. En conséquence, nous avons choisi des enregistrements parmi les meilleurs, qui ont vraisemblablement été écoutés par Elvis avant qu’il n’en grave lui-même une version. Une bonne occasion de fondre au son de la voix de la sublime Mahalia Jackson11. Quoiqu’il en soit, il était osé d’enregistrer des morceaux aussi connus derrière des interprètes du calibre de Mahalia Jackson, Clyde McPhatter (l’un des grands précurseurs de la soul music) ou dans une moindre mesure, Stuart Hamblen, une grande vedette du gospel blanc. Mahalia était simplement indépassable, mais Elvis chante ici avec sincérité et aisance et le résultat de ses versions est plus que satisfaisant.

Musique populaire

On peut apprécier ici les aller-retour des compositions entre styles blancs et noirs et ce de façon caractéristique sur le grand standard Blueberry Hill, écrit pour le chanteur country Gene Autry à l’occasion du film Singing Hill (Lew Landers, 1941), repris par le groupe vocal Steve Gibson & The Red Caps très influencé par le style de groupes vocaux comme les Mills Brothers ou les Ink Spots (que l’on peut déguster ici sur l’exquis That’s When Your Heartache Begins enregistré en 1941). Mais c’est bien sûr Fats Domino, vedette du rhythm and blues depuis le début des années 1950, qui en 1957 a gravé la plus célèbre version de Blueberry Hill dans un style typique de la Nouvelle-Orléans - dont Elvis a copié l’arrangement.

Dans le cas où il n’existe pas d’enregistrement antérieur à la version de Presley, seule sa version a été retenue. On peut donc savourer ici les influences diverses qui ont construit le répertoire de l’icone du rock and roll, du rhythm and blues d’Otis Blackwell à la country de Red Foley, de la comédie musicale de Bing Crosby et Grace Kelly (future princesse Grace de Monaco) au gospel noir de Mahalia Jackson pour qui Thomas A. Dorsey a écrit Take my Hand, Precious Lord. Et on appréciera particulièrement la pureté des arrangements (créés par Elvis lui-même), débarrassés des lourdeurs orchestrales surannées entendues sur les titres de Bing Crosby et Stuart Hamblen notamment.

Le rock and roll n’est pas pour autant en reste. En 1957 lors d’un nouveau sommet, cette fois-ci cinématographique, Elvis grava Jailhouse Rock pour la bande du film du même nom. En empruntant le génial tandem d’auteurs compositeurs Jerry Leiber et Mike Stoller à l’équipe des disques de rhythm and blues Atlantic (ils écrivaient pour les Drifters, les Coasters, monstres sacrés du genre), Elvis travaillait avec les meilleurs qui lui donnèrent Loving You, Hot Dog, Santa Claus Is Back in Town, (You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care, I Want to Be Free et Jailhouse Rock. C’est avec une intuition certaine qu’en accord avec son imprésario Tom Parker, Elvis Presley a pris le chemin de la diversification de ses activités. Déjà devenu l’un des grands mythes américains, il continua sans lâcher son groupe, le guitariste Scotty Moore, le contrebassiste Bill Black et le batteur DJ Fontana que son manager trouvait envahissants.

Contrairement à Gene Vincent, Bo Diddley ou Chuck Berry qui enregistraient en un temps record des morceaux souvent déjà rodés sur scène, les séances d’enregistrement du roi du rock étaient organisées comme des marathons. Coincées dans un agenda serré, où de nouvelles chansons étaient proposées, choisies, travaillées et gravées sur le champ après un grand nombre de prises, elles font parfois regretter la simplicité essentielle, le son rockabilly limpide, l’énergie, la magie de la production de Sam Phillips pour Sun en 1954-1955. Si la sobriété élégante des arrangements dirigés par Elvis font vite oublier les versions originales de morceaux country comme Old Shep ou Have I Told You, l’ironie veut que pour le rock/rhythm and blues, les versions de Steve Gibson and the Red Caps, Fats Domino (Blueberry Hill), Smiley Lewis et surtout de Little Richard restent indétrônables. Il n’en demeure pas moins que les morceaux dont il interprète lui-même les versions originales, des monstres sacrés du rock comme Jailhouse Rock, Teddy Bear ou All Shook Up comptent parmi les plus immuables chefs-d’œuvre de la musique populaire américaine.

Bruno Blum

Merci à Georges Blumenfeld, Katia Dahan, Lucky Haddad et Gilles Pétard.

© 2012 GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SAS

1. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA 5361) dans cette collection.

2. Peter Guralnick, Elvis Presley - Last Train to Memphis, vol. 1 : le temps de l’innocence, 1935-1958 (1994. V.f. : Le Castor Astral, Paris, 2007).

3. Jazz Hot, décembre 1956. Boris Vian, Chroniques de jazz (la Jeune Parque, Paris, 1967).

4. Écouter Little Richard - The Indispensable - 1956-1960 (à paraître dans cette collection).

5. Écouter Bo Diddley - The Indispensable - 1955-1960 FA5376. Un deuxième volume à paraître en 2013.

6. Écouter Gene Vincent & His Blue Caps (deux volumes à paraître dans cette collection).

7. Jazz Hot, décembre 1957. Boris Vian, Chroniques de jazz (la Jeune Parque, Paris, 1967).

8. Écouter la série d’anthologies Gospel dans cette collection (FA 008, FA 026, FA 044, FA 5053).

9. Écouter Jamaica - Trance Possession Folk 1939 - 1961 dans cette collection (à paraître chez Frémeaux et Associés début 2013).

10. L’œuvre intégrale de Sister Rosetta Tharpe est disponible dans cette collection.

11. L’œuvre intégrale de Mahalia Jackson est disponible dans cette collection.

Elvis Presley & The American Music Heritage

Critics judge works and do not know that the latter judge critics.

Jean Cocteau

It’s always the same old tune: «After those first rock hits, Elvis Presley was just a load of mush.» The army, his acting career, a greedy manager… any reason would do, they were all used to accuse the young singer of betraying the good cause, i.e. rock. And Elvis was its King. But what really happened? Who really listened to the records said to incriminate him? What were his inspirations, the sources of his music, during that next part of his life? Did Elvis really abandon those who saw him as a symbol of the rock and roll generation, the singing counterpart of James Dean, the resurrection of the rebel without a cause…? In a word, had Elvis switched sides?

There’s even more reason to ask the question when you realise that, in 1956, rock ‘n’ roll seemed doomed: it looked to be a passing fad, like mambo, calypso and, soon, bossa nova. The general opinion was that such a disturbing fashion wouldn’t last. Nobody could have predicted that rock would become a central form of expression for adolescents, or that it would last for so long.

Triumph

With the despicable hatchet of the Second World War finally buried – even the Korean War was over by the summer of 1953 – a new generation sprang up with a greed for liberty and letting the good times roll. But eight years before Beatlemania, who could have guessed how important the rock music genre was going to be? Who could ever foresee that rock culture, an essentially marginal, generational statement of identity and the ‘rock attitude’ cliché would have such an impact on young people for decades to come? With hindsight, you realize that the attitude adopted by Presley at his most glorious peak still has enormous symbolic value. And to young Americans of the period, his career choices had even more importance than that.

Frank Sinatra’s success in the early 40’s had been similar, but he’d had to wait for films and the Golden Age of Hollywood to consecrate his status. Radio was in its initial stages and television almost inexistent, so Sinatra had no mass media behind him, which reduced his impact: even if his concerts unleashed the fervour of bobbysoxers, the music and choreography of Ol’ Blue Eyes in action caused nowhere near the brush-fire propagated by rock and roll, to say the least. Elvis’ concerts and (suggestive) spontaneous swivelling, on the other hand, stirred collective hysteria within seconds: the continual screaming of teenagers who’d lost control drowned out the sound of his musicians, and they couldn’t even hear their own drums onstage. The new invention called television suddenly transported the revelation of Elvis’ impact into the heart of conservative America, and conservative America didn’t like being rocked. Elvis was suddenly there, after a lightning-fast success-story without precedent in American history: the sales of his discs – and the size of his television-audience – went into the record-books, like his first film «Love Me Tender» (1956), and seduced a public that was young, not so young, black, white, Latin, southern, northern… and not even restricted to America for that matter. Elvis was prodigious. The sales charts – pop, (white) country & western, even R&B (black music styles charts were separate, segregation oblige) – were stormed by hits: Hound Dog, All Shook Up (the David Hill version here was released a few weeks before Elvis’ record), or (Just Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear. Elvis the insomniac, together with his crew, hardly neglected a single State in a tight schedule that saw them travelling by plane, train, bus and Cadillac.

It hadn’t been two years since the days when Elvis had literally never left home. His family had been through poverty, leaving the misery of Tupelo at the end of 1948 in search of a better life in Memphis; the three of them lived together in one room for a long time before they were finally housed by the government. Elvis loved music, and after working as a labourer he was driving a truck for pennies when his first record was released. His first masterpiece1. Dumbstruck by what was happening to him, Elvis could only repeat that he owed his phenomenal triumph to a stroke of luck: it was the hand of God which permitted him to buy a large house for his family, and keep Cadillacs in his garage. Totally unprepared for glory at the age of 21, the young, self-taught star was constantly in the spotlight, and the pressure was enormous.

backfire

Elvis’ affairs were difficult to handle, and since early 1955 they’d been managed by a rough, tough, merciless, brilliant and devoted impresario named «Colonel» Tom Parker. The situation was further complicated by increasing criticism that was unfair, biting and malevolent. One has to understand that the pop music of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin or Bing Crosby – popular singers who’d become film stars – was hardly a threat to established order, at least where the latter’s public and film appearances were concerned. Even in a film which had the smack of heresy – like the remarkable «The Man with the Golden Arm» (Otto Preminger, 1955), where the talented Sinatra played a jazz drummer addicted to heroin – moral standards were respected, as in all of Hollywood’s happy-end movies. White singers from the southern United States had also had hits, among them Hank Williams, Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, Stuart Hamblen, Hank Snow or Eddy Arnold (the latter had three N°1 hits in 1947, and Tom Parker had been his manager too, before taking care of Hank Snow and then Presley). Nevertheless, Elvis was more than just a talent who worked at his trade, and more than just a singer: he was an unthinkable phenomenon. In this respect, his slightest deeds and gestures came under scrutiny. As shown in the first volume in this series – devoted to the first three years of his career – there was no general agreement as to what Elvis represented in that alarming context of strict racial segregation, particularly when it came to the Afro-American connotations of his music and dancing. On May 17th 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court laid down that racial segregation in schools was against the constitution, and President Eisenhower ordered the desegregation of the education-system. Just look at what happened: in 1957, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas sent the National Guard out to schools in Little Rock (a few miles from Memphis, where the Presleys lived…) to prevent black children from attending classes. Eisenhower relieved Faubus of his National Guard command, and sent in the Army to escort the children to school.

If young people could have voted, they’d have voted for Presley, so parents were rarely indifferent to Elvis. Some of them appreciated him, while some of the more conservative ones cursed him as a trouble-maker. Extremely negative reactions to Presley multiplied in 1956. What sort of criticism was levelled against him? If you read the remarkable Presley biography by Peter Guralnick2, you realise that in the summer of 1956, Elvis hadn’t ever yet faced such a vast wave of personal attacks and accusations of indecency. «Mr. Presley has no discernible singing ability,» asserted Jack Gould in the (moderate) daily New York Times. Conservative columnist Jack O’Brian criticized the singer in the New York Journal-American for “caterwauling his unintelligible lyrics in an inadequate voice, during a display of primitive physical movement… difficult to describe in terms suitable to a family newspaper.» The Daily News reported Ben Gross as saying that popular music had «reached its lowest depths in the ‘grunt and groin’ antics of one Elvis Presley… an exhibition that was suggestive and vulgar, tinged with the kind of animalism that should be confined to dives and bordellos.» The Catholic weekly America sent its own message in a column whose title said it all: «Beware of Elvis Presley.» Other statements demonizing him, particularly those made by religious leaders, deeply wounded Elvis the believer, who had learned to sing and play guitar mostly at the First Assembly of God Church in East Tupelo. Controversy spread across the Atlantic also, and in France, in one of Boris Vian’s famous jazz chronicles3, the famous French author/trumpeter quoted a British jazz journal whose hostility to rock was ironic, given that the paper later became the greatest British rock weekly: in the October 20th 1956 issue of Melody Maker, critic Steve Race wrote (in one of his more restrained observations) that Elvis’ arrival was «infantile and often suggestive chanting.» Race added that he feared for the future of the rock ‘n’ roll industry if it «lowered itself to satisfying the demands of a mad group of juveniles, to the detriment of the much greater number of those who want to listen to songs sung cleanly and in tune.»

Vian added: «Steve Race was wrong about the industry, but as for the music, at least where Presley was concerned, he was quite correct. Anyway, industry and music are different concepts altogether…»

As for cornet-player Boris Vian, who had some disdain for rock music, he knew what he was talking about: he’d just written the first French rock songs in history for Henri Salvador («Rock and roll mops») and Magali Noël (the excellent “Fais-moi mal, Johnny”). There were few places where Elvis wasn’t the victim of slander and mockery, but when you listen to his renderings here of such difficult melodies as I Need You So or O Little Town of Bethlehem, there’s no way you can accuse Elvis of singing out of tune.

To be honest, several elements sent America into trauma. First, there was the sensuality emanating from the way Elvis «moved». It was deemed improper by an extremely Puritan America, little accustomed to seeing suggestive images on television at home. The excitement and dizziness caused by rock and roll made viewers completely forget its musical merits. The period was as heavy as lead: before the sexual freedom that came with the Sixties, American womenfolk negotiated their virginity with marriage in mind. Girls weren’t touched, and petting in private was flirting’s summum genus. In the highly conservative South, girls who broke that rule were extremely rare. Between 1954 and 1957, as a seducer desired by tens of millions of women, Elvis «flirted» durably with several ladies, among them Dixie Locke before fame came along, and then June Juanico, Dottie Harmony, actress Natalie Wood – in 1955 she had played opposite James Dean in Nicholas Ray’s cult movie Rebel Without A Cause – or Yvonne Lime. But they all slept in separate beds and none had a sexual relationship with the singer. Anyway, his manager stood in the way of anything and everything that might harm Elvis, whose career was Parker’s sacrosanct N°1 aim: Tom Parker strictly forbade him from marrying, and in fact said hardly a word to any of the above. According to some of the musicians, however, it’s known that Elvis did manage to spend the night with some of the women he met. It’s also known that Elvis saw erotic films at screenings organised by his friends, but those occasional deviations from the straight and narrow aren’t enough to make one forget the cruel reality of the sex symbol: Puritanism, frustration, repression, the very occasional groupie, masturbation, disappointment for several women in love, and general hypocrisy for all.

Secondly, as explained in detail in Vol. 1 of this series, rock and roll was fundamentally Afro-American music. Presley and his crew performed it with the addition of a «country» hue – especially with Scotty Moore’s electric guitar and a repertoire that was partly country-music –, giving birth to the new rockabilly genre. Elvis managed to sing two songs at the temple of country music they called the Grand Ole Opry, which agreed to invite Elvis as a favour to his first producer, Sam Phillips. But, like most of the public, the conservative management of the Opry thought Elvis’ style was foreign to «country music culture» and didn’t invite him again despite his triumph there. While it’s true that bluegrass icon Bill Monroe was quick to salute Elvis’ talent – he recorded in turn his own «Blue Moon of Kentucky» in the new rockabilly style, to the stupefaction of the C&W milieu –, it is also true that, for a major part of the population, Presley’s music was above all a sign of Afro-American integration, and this was still another threat to white dominance (just when Martin Luther King’s movement was getting off the ground and into the newspapers). Feelings were running considerably high in Elvis’ home State of Tennessee, also the home of the Ku Klux Klan. Nothing concrete came of it, nor was anything written for publication, but all the same, it was being given some thought. As the New York Journal-American had done, people preferred speaking in metaphors, using terminology like «primitive movements», «bestiality» or «insult»; everyone knew what they meant. When Elvis appeared at an Afro-American charity concert on December 7th 1956 and had his photograph taken with B.B. King, the period’s great blues star (he also lived in Memphis), the message was seen as an extreme provocation: right in the middle of segregation, Elvis Presley wasn’t hiding the fact that he had Afro-American friends. The ‘Afro’ press cheered his commitment and Elvis’ recognition of his musical debt to the black community: many of whom considered Elvis a popular hero. Six months later the Afro-American journal Memphis World published an article saying that Elvis had «braved the segregationist laws of Memphis» during what they called a «night for colored people.» A few Afro-American journalists didn’t like Elvis borrowing from the rhythm and blues repertoire which he «exploited»; especially, they were jealous of how seductive Elvis seemed to black teenage girls («Colored Girls Go Haywire Over Elvis Presley» said the Pittsburgh Courier). But the attraction he had for women particularly upset most of the white, middle-class population – especially those over twenty – for whom interracial love-affairs were totally inconceivable.

After «Tutti Frutti» on his first album, the second LP («Elvis», released in October 1956) contained no fewer than three ‘covers’ of songs by Little Richard (included here), the wildest and most outrageous of the rockers - and he was black. Early on, Little Richard was eclipsed by Elvis, who’d helped put his «Tutti Frutti» on everyone’s lips, but Little Richard quickly took flight on his own, with rock fans running for shelter as he dropped bomb after irresistible bomb4. Elvis helped himself to four titles from Little Richard’s fantastic repertoire, and committed the irreparable: in the wake of Elvis black rockers came pouring into markets which up until then had been the exclusive province of white artists (beforehand, only the calm and collected Fats Domino had enjoyed that privilege). To cap it all, rock was indeed threatening the established music-industry by introducing new musical criteria and a brand-new attitude towards race. In 1955-1957 Bo Diddley slipped several very original hits into his bag5, and Chuck Berry reached white audiences with hit after hit. Elvis did Chuck’s Maybellene onstage and loved Brown Eyed Handsome Man, Chuck’s plea for black/brown justice.

Meanwhile, white rock was being born, and it was getting organised. In Memphis, Sam Phillips had debts to pay and he was obliged to sell Elvis Presley’s contract to RCA for a few thousand dollars. He tried to start over by launching other young rockabilly artists on his independent Sun Records label: Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and soon Roy Orbison, all of whom had big hits. In Hollywood, Capitol Records riposted by signing a new white artist who was brimming with talent (as was his dazzling guitarist, Cliff Gallup): Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps6 took off with their irresistible «Be-Bop-a-Lula» in 1956. Many thought that this song was sung by Elvis, and when Gene Vincent met Presley, the former was quick to say how sorry he was. Still in Hollywood, films with rock as their theme came thick and fast: after Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), which revealed Bill Haley to the world, there was Rock Rock Rock with the famous disc-jockey Alan Freed, The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956) and others, including Elvis’ screen-debut in Love Me Tender (Robert D. Webb, November 21st 1956).

In summer 1956 criticism was constant and insulting, and despite Elvis’ success, his minor role in Love Me Tender was mocked. There was also a payola scandal, with songwriters signing over some of their royalties to publishers – in exchange for access to the media, although the practice wasn’t restricted to rock and roll – and to famous singers, Elvis among them. In December 1957 Boris Vian wrote: «In the ‘Melody Maker’ of November 2 it’s interesting to discover a cheering aspect of Elvis Presley […] Here is what this cynical character jovially declares (actually a compliment; his frankness deserves our appreciation): ‘I’ve made more than a million dollars this year’ – he says to Howard Lucraft, his interviewer – ‘but I’m no musician. I can’t play guitar and I’ve never written a song in my life. But I put my name on the ones I do, and I get a third of the royalties on all the songs I sing.’ And he goes on to add, smiling in derision, ‘In those conditions it would be pretty stupid to learn music.» This is America, of course… but it happens sometimes in France. In France, unfortunately, certain artists put their names to music which they write, because they’re honest… but they don’t know how to write music any more than Presley does. So, what can you do? Listen to Sinatra7.»

The criticism wasn’t true: Elvis continued, under an arrangement set up by Tom Parker (common at the time), to ensure he received part of the royalties due on a few of the songs he performed, notably those of Otis Blackwell (who was black, incidentally). But he put a stop to the practice at the end of 1956. As a barely disguised attack on this music of racial integration coming in the midst of the civil rights movement – it began when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white man on December 1st 1955 – the Payola scandal made a great deal of noise and did considerable harm to rock and roll. In 1959 it put an end to the career of Alan Freed, the emblematic rock DJ/non-conformist television personality who’d popularised the expression «rock and roll» as early as 1951, and had always supported Afro-American artists. Freed’s troubles started after a complaint by ABC associates in the South, who didn’t like seeing the teenage singer Frankie Lymon dancing with a young white woman on one of Freed’s shows. Other DJs with rock associations, like Dick Clark, would get into similar trouble in 1959. Freed was fired, few stations would employ him, and the broken man became an alcoholic, dying of cirrhosis. Enter the reactionary forces of America: the lucrative record-industry wasn’t going to let anyone rock the boat with «primitive» music (listen to the contemporary pop atmosphere on I Believe by Jane Froman here, or the original version of It Is No Secret, an enormous white gospel hit for Stuart Hamblen). Even so, Hamblen’s It Is No Secret (What God Can Do), where «God can do for you what he’s done for others», was Elvis’ sincere and «autobiographical» way of thanking the Lord for his success.

But at the same time as the moderate Elvis was publicly declaring he favoured Democrat Adlai Stevenson to run as Presidential Candidate against Dwight Eisenhower, a good part of America was now seeing rock and roll as the music of the devil. A year after Eisenhower was re-elected, Little Richard, under unimaginable pressure, threw in the towel and followed God, abandoning a fabulous career as a rock singer after a bunch of masterpieces. Like Elvis, Little Richard would turn to gospel. Bo Diddley was boycotted by television at the insistence of Ed Sullivan, who’d quarrelled with Bo after a misunderstanding in which racism played a part. In 1962/63, after more than one appeal, Chuck Berry served 18 months in prison for a 1959 sex-offense against a (white) minor. A similar scandal involved Jerry Lee Lewis in May 1958 (he married a thirteen year-old, not uncommon practice in the Deep South) and he also disappeared from the scene. The Big Bopper, Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran lost their lives in accidents that remain mysteries. And Gene Vincent, grievously injured in the accident which killed his friend Cochran in 1960 – and with only one big hit despite some extraordinary records – also saw his career come to an abrupt end.

In 1956, after a silver lining behind the clouds of racial tension, rock had already become the lightning-conductor used to stigmatize a whole new generation. Elvis couldn’t stand being criticized by people who «didn’t know him». To make matters worse, and contrary to the image of a vulgar, debauched savage which had been condescendingly given to him in certain sectors of the media, Elvis was a young man of great innocence and gentleness, perfectly sincere, and almost pathologically polite. He lacked maturity – his mother and manager brooded over him like hens – but he was well-behaved, very pious, and his humility was proverbial; he tried to «do his best» in this maelstrom where, to his great disliking, he appeared as a rebel. He was so polite and well-intentioned that he accepted to appear on television singing «Hound Dog», dressed in tails with a dog for company, and he wasn’t allowed to dance. He was made to look ridiculous and his fans protested massively. It was all too much. Elvis Presley had to deal with it and find an answer carrying as much weight as the blows which rained down on him. His incredible success seemed unshakeable whatever he did, but for the Colonel, the time had come for him to move on.

Gospel

Fashion goes out of fashion; style, never.

Coco Chanel

As early as the beginning of 1956, Parker logically made plans to put the myth of Elvis on film. After a screen-test, Elvis signed lucrative contracts for several movies; the enormous success of Love Me Tender that summer encouraged him to persevere, and in 1957 came Presley’s best film, Richard Thorpe’s Jailhouse Rock. Elvis was delighted with this new orientation. He trusted his domineering manager completely – Parker was 25 years his elder – and, so far, his career had been managed with flair, albeit with an iron hand. «Colonel» Parker had also incited his protégé to vary his repertoire, and Elvis couldn’t have asked for more: he had already proved himself as a rock singer. After all, hadn’t it been the idea of his first producer, Sam Phillips, to turn him into what he’d become? Elvis had stated more than once that, if the formula worked, it would be wrong for him to change it, but who could blame him now for looking to do something new? He’d never hidden his intention to succeed as a singer of country and western songs, ballads, pop songs… Elvis Presley was more than a grand-sounding «King of Rock»: deep down, he had a vocation as a talented popular singer and, more than anything else, he wanted to record gospel songs, the first music he’d heard at the Assembly of God in Tupelo. Religion had greatly contributed to structuring the black community. Negro spirituals and gospel songs were performed with fervour at Revivalist camp-meetings, of course, not to mention churches and other Afro-American temples. Elvis liked wandering through the streets bordering the black districts of Memphis, which were filled with the spiritual power emanating from the Christian8 and Revivalist9 gatherings where the faithful went into trances during their services. The spectacle is difficult to imagine for anyone who hasn’t actually participated in them. But the young Elvis had grown up to the sounds of the Assembly of God, a white Church where the gospel style was different – certainly less exuberant – but where, like Jack Hess (whom he greatly admired), the boy could come in contact with Faith and religious music. The Assembly of God had practised a certain kind of racial mix until it had been banned by Jim Crow/segregationist laws in the Twenties, and Elvis never missed a chance to sing gospel, the privileged domain of racial reconciliation. He did exactly that with the astonishing «Million Dollar Quartet» – with Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash – during an informal session at Sun Studios in December 1956, but also with James Brown after meeting the «Godfather of Soul». The young Elvis had a well-mannered way of life – he hated alcohol and tobacco, and banned them from his home – and it corresponded to what he heard on gospel records made by The Clara Ward Singers, Sister Rosetta Tharpe10 or Mahalia Jackson who, in 1956, became the genre’s Queen and an international celebrity. Elvis couldn’t help being deeply impressed by that dazzling black gospel, but he showed a natural liking for white gospel vocal-groups such as the Blackwood Brothers, or the Statesmen Quartet with his great influences Jake Hess and «Big Chief» Wetherington, with Elvis imitating the latter’s dance-steps even though they shocked ecclesiastics. The Jordanaires – a famous Southern Gospel vocal-harmony group – were Elvis Presley’s own choice to accompany him in the studios and onstage from January 1956 onwards. The Jordanaires were among the first white professional gospel groups to sing Negro spirituals and, like Elvis, to integrate the influence of black gospel. The singer insisted that their prestigious name should appear alongside his own on his records – at a time when accompanists were never credited.

So it came as no surprise when the young star accepted an offer from his publishers (who held part of the rights to several of the genre’s most famous pieces, among them songs by the great modern gospel composer Thomas A. Dorsey) to record hymns and Christmas songs. As always, Elvis dug deep into a repertoire of tried-and-trusted songs like I Need You So by Ivory Joe Hunter, which was an R&B N°1 in 1950. Like the previous volume, this set presents Elvis’ performances alongside recordings of other versions of the compositions which inspired him. However, concerning pieces like White Christmas (one of Bing Crosby’s greatest hits), or the Silent Night classic (a 19th century composition with innumerable other versions), it’s quite difficult to find the precise source which inspired Elvis. Take Peace in the Valley for example: Presley had been singing this classic since he was a teenager, and it had already been covered by country-artist Red Foley. Consequently, we have chosen recordings from amongst the best versions which were most likely to have been listened to by Elvis before he recorded his own versions of them. It’s a great chance to melt into the sublime voice of Mahalia Jackson11. Whatever the true source of some of these, however, no-one can say that Elvis lacked audacity when he recorded these pieces after others had already done so, artists of the calibre of Mahalia Jackson, Clyde McPhatter (one of the great Soul precursors) or, to a lesser degree, Stuart Hamblen, a great white-gospel star. Mahalia was simply peerless, but Elvis’ renditions here are so sincere that the result is (much) more than satisfactory.

Popular music

This selection allows you to appreciate the way these compositions cross back and forth between white and black styles, a characteristic of the great standard Blueberry Hill written for country-singer Gene Autry and the film «Singing Hill» (Lew Landers, 1941), which was covered by the vocal group Steve Gibson & The Red Caps; they were highly influenced by the style of vocal groups like The Mills Brothers or The Ink Spots (and you can taste their music here on the exquisite That’s When Your Heartache Begins, recorded in 1941). The most famous version of Blueberry Hill however, remains the one by Fats Domino, a rhythm and blues star since the early Fifties; Fats recorded his version in 1957 in a typically-New Orleans style, and Elvis used its arrangement. Where no previous recordings exist by others, only Elvis Presley’s version is included; here you can savour various influences which formed the repertoire of the rock ‘n’ roll icon, from Otis Blackwell’s rhythm and blues to the country of Red Foley, and from musicals (Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly, the future Princess Grace of Monaco) to the black gospel of Mahalia Jackson for whom Thomas A. Dorsey wrote Take my Hand, Precious Lord. You can also appreciate the purity of the arrangements written by Presley himself, with none of the heavy, dated orchestration heard notably on titles by Bing Crosby or Stuart Hamblen.

Not that rock and roll was left in the background: in 1957, at a new peak in his career, this time in films, Elvis cut Jailhouse Rock for the soundtrack of the film of the same name. In working with composing-teams of genius – Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller, both house-writers at the R&B label Atlantic, were the team behind giants like The Drifters and The Coasters – Elvis ensured he was partnered by the best, and they gave him Loving You, Hot Dog, Santa Claus Is Back in Town, (You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care, I Want to Be Free and Jailhouse Rock. Elvis showed his intuition when, agreeing with his impresario Tom Parker, he opted to diversify his activities. He was already an American myth, but stayed with the same great group – guitarist Scotty Moore, bass-player Bill Black and drummer DJ Fontana – despite the fact that his manager found them invasive. Unlike the sessions of Gene Vincent, Bo Diddley or Chuck Berry, who spent little time in the studios after ‘rehearsing’ many pieces onstage in concerts, the King’s sessions were organised like marathons. Presley’s dates kept to a very tight schedule in which new songs were put forward, selected, worked on and recorded all at the same time, with many takes involved; the method sometimes made people regret the essential simplicity, the clear rockabilly sound, energy and magic of Sam Phillips’ productions for Sun in 1954-1955. If the elegant sobriety of the Elvis arrangements caused the original versions of country pieces like Old Shep or Have I Told You to be quickly forgotten, it’s ironic that where rock or rhythm and blues were concerned, the versions of Steve Gibson and the Red Caps, Fats Domino (Blueberry Hill), Smiley Lewis and especially Little Richard remain unassailable. Nonetheless, the pieces whose original versions were those Elvis performed himself – monster rock-titles like Jailhouse Rock, Teddy Bear or All Shook Up – remain invincible masterpieces of American popular music.

Bruno BLUM

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Georges Blumenfeld, Katia Dahan, Lucky Haddad and Gilles Pétard.

© 2012 GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SAS

1. Cf. Elvis Presley & The American Music Heritage 1954-1956 (FA 5361) in this collection.

2. Peter Guralnick, Last Train to Memphis – The Rise of Elvis Presley, Abacus 1995.

3. Jazz Hot, Dec. 1956. Boris Vian, Chroniques de jazz (Publ. La Jeune Parque, Paris, 1967).

4. Cf. Little Richard - The Indispensable - 1956-1960 (future release in this collection).

5. Cf. Bo Diddley - The Indispensable - 1955-1960 (available in this collection, FA5376. Volume two is a future release).

6. Cf. Gene Vincent & His Blue Caps (two volumes to be released in this collection).

7. Jazz Hot, Dec. 1957, Boris Vian, Chroniques de jazz (la Jeune Parque, Paris, 1967).

8. Cf. the Gospel series of anthologies in this collection (FA 008, FA 026, FA 044, FA 5053).

9. Cf. Jamaica - Trance Possession Folk 1939 - 1961 in this collection (future Frémeaux release in 2013).

10. The complete recordings of Sister Rosetta Tharpe are available in this collection.

11. The complete recordings of Mahalia Jackson are available in this collection.

Lorsqu’une œuvre semble en avance sur son époque, c’est simplement que son époque est en retard sur elle.

Jean Cocteau

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 1

1. Long Tall Sally - Little Richard

2. Long Tall Sally - Elvis Presley

3. Old Shep - Red Foley

4. Old Shep - Elvis Presley

5. Too Much - Bernard Hardison

6. Too Much - Elvis Presley

7. Any Place Is Paradise - Elvis Presley

8. Reddy Teddy - Little Richard

9. Reddy Teddy - Elvis Presley

10. First in Line - Elvis Presley

11. Rip It Up - Little Richard

12. Rip It Up - Elvis Presley

13. I Believe - Jane Froman

14. I Believe - Elvis Presley

15. Tell Me Why - Marie Knight

16. Tell Me Why - Elvis Presley

17. Got a Lot o’ Livin’ to Do! - Elvis Presley

18. I’m All Shook Up - David Hill

19. All Shook Up - Elvis Presley

20. Mean Woman Blues - Elvis Presley

21. peace in the Valley - Red Foley

22. peace in the Valley - Elvis Presley

(1) (Richard Penniman, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps, Enotris Johnson) Richard Penniman aka Little Richard-v, p/Justin Adams-g/Rene Hall-g/Edgar Blanchard, b/unknow, bs/Lee Allen-ts/Earl Palmer-d. Recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s Cosimo Studio, 523 Governor Nicholls St., New Orleans, Louisiana, February 3, 1956.

(2) (Richard Penniman, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps, Enotris Johnson) Elvis Aaron Presley aka Elvis Presley-v, occasional g or p; /Winfield Scott Moore II as Scotty Moore-g/William Patton Black as Bill Black-b; Dominic Joseph Fontana as D.J. Fontana-d; Gordon Stoker-p; The Jordanaires: Neal Matthews-v; Hugh Jarrett-bass v; Hoyt Hawkins-v; Gordon Stoker-v. Recorded at Radio Recorders, Hollywood, September 1-3, 1956.

(3) (Clyde Julian Foley a.k.a. Red Foley, Arthur Willis) Clyde Julian Foley a.k.a. Red Foley-g, v/Ozzie Westley-g; Clyde Moffett-b; Harry Simms-v; Aigie Klein-acc. Recorded in Chicago, March 4, 1941.

(4) (Clyde Julian Foley a.k.a. Red Foley, Arthur Willis) same as (2). Fontana out.

(5) (Bernard Weinmann, Lee Rosenberg) Bernard Hardison-v, p. Personnel unknown. Recorded in Nashville, 1955.

(6) (Bernard Weinmann, Lee Rosenberg) same as (2). Piano out.

(7) (Joe Thomas) same as (2).

(8) (John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps) Richard Penniman aka Little Richard-v, p/Justin Adams-g/Frank Fields-b/Alvin Tyler aka Red-bs/Lee Allen-ts/Earl Palmer-d. Recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s Cosimo Studio, 523 Governor Nicholls St., New Orleans, Louisiana, April, 1956.

(9) (John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps) same as (2).

(10) (Aaron Schroeder, Ben Weisman) same as (2).

(11) (John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps) same as (CD1, track 8).

(12) (John Marascalco, Robert Blackwell a.k.a. Bumps) same as (2).

(13) (Ervin Drake, Irvin Graham, Jimmy Shirl, Al Stillman) Jane Froman and The Jane Froman Show Orchestra (CBS Television). Recorded December 23, 1952.

(14) (Ervin Drake, Irvin Graham, Jimmy Shirl, Al Stillman) Elvis Presley-v, g;Winfield Scott Moore II as Scotty Moore-g; William Patton Black as Bill Black-b; Dominic Joseph Fontana as D.J. Fontana-d; Gordon Stoker-p; The Jordanaires: Neal Matthews-v; Hoyt Hawkins-v; Gordon Stoker-v; Hugh Jarrett-bass v. Recorded at Radio Recorders, Hollywood, January 12-13, 1957.

(15) (Titus Turner) Marie Knight w/The Griffins. Marie Knight-v; William Ross-v; Bill Alford- first tenor v; Lewis Thompson a.k.a. Flip-second tenor v; Lawrence Tate-Baritone v; Joshua Bright-bass v. Personnel unknown. Recorded in 1956.

(16) (Titus Turner) same as (14).

(17) (Aaron Schroeder, Ben Weisman) same as (14).

(18) (Otis Blackwell) David Alexander Hess as David Hill-v; Personnel unknown. Recorded in 1956.

(19) (Otis Blackwell, Elvis Presley) same as (14).

(20) (Claude Demetrius)

(21) (Thomas A. Dorsey) Red Foley & The Sunshine Boys Quartet. Clyde Julian Foley a.k.a. Red Foley-v. Personnel unknown. Produced by Paul Cohen. Recorded at Castle Studio, Tulane Hotel, 206 8th Avenue North, Nashville 3, Tennessee, March 27, 1951.

(22) (Thomas A. Dorsey) same as (14).

DISCOGRAPHIE CD 2

1. That’s When Your Heartaches Begin - The Ink Spots

2. That’s When Your Heartaches Begin - Elvis Presley

3. Take my Hand, precious Lord - Mahalia Jackson

4. Take my Hand, precious Lord - Elvis Presley

5. It Is No Secret - Stuart Hamblen

6. It Is No Secret - Elvis Presley

7. Blueberry Hill - Gene Autry

8. Blueberry Hill - Steve Gibson & The Red Caps