- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

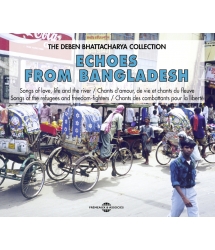

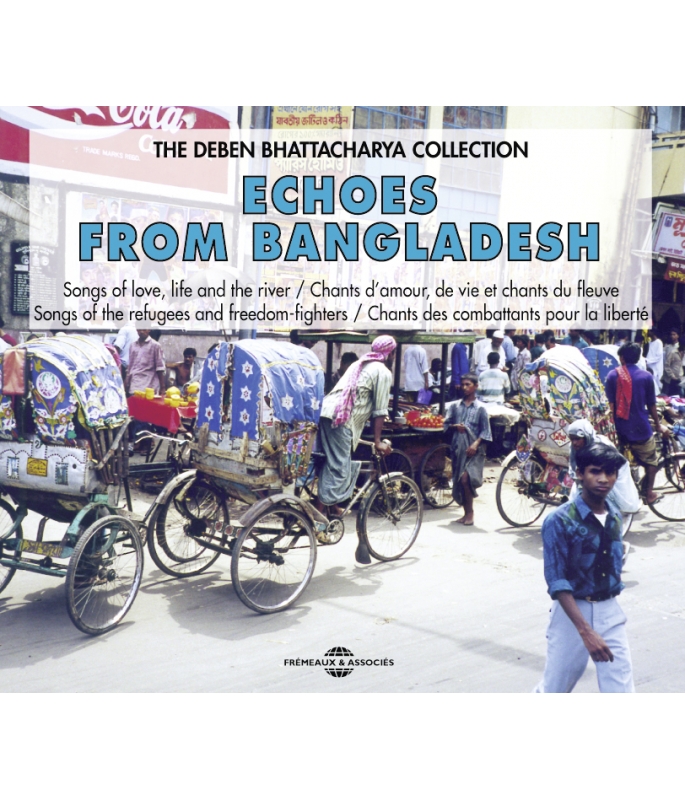

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

Ref.: FA161

EAN : 3448960216128

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

- - SÉLECTIONNÉ PAR RÉPERTOIRE

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

(2-CD set) These two cds represent for the first time two distinct but intrinsically important Bangladeshi themes : traditional songs of love and life in the river country and the songs of the Freedom Fighters which played a vital role in influencing the birth of Bangladesh out of the ashes of East Pakistan. Includes a 40 page booklet with both French and English notes.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1BHATIAL GANGER NAIYATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:561954

-

2UJAN GANGER NAIYATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:05:581954

-

3MAYNAMATIR GANTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:061954

-

4ULTA DESHTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:061954

-

5ASHOLE BINASH HOILATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:461954

-

6SHARANATHIR GANTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:491954

-

7DOTARATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:07:101954

-

8AMI TOMAY BHALOBESHETRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:05:391997

-

9MANUSH BANAICHHE ALLAHTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:271997

-

10MURSHIDITRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:08:031997

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1NIJER PAYE NIJE HETE CHALTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:471971

-

2KOIONA KOIONA BANDHURETRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:141971

-

3SURJA UDALA LAL MARITRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:03:181971

-

4CHOTO CHOTO DHEUTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:05:371971

-

5MALKHA BANUTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:03:451971

-

6MATIR MANUSHTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:04:041971

-

7JANMABHUMI JANANITRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:02:491971

-

8TOMAR BANGLA AMAR BANGLATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:01:591971

-

9PAL TULE DETRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:02:001971

-

10GURU TUMI AMAR EI GOLAR I HARTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:02:421971

-

11MON TUMI DARSHANATE GELENATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:03:171971

-

12MON PABANER NAIYATRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:03:501971

-

13HAI SHEIKH MUJIBARTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:06:581971

-

14EKBAR PHIRE CHAO HE PRANESHWARTRADITIONNELTRADITIONNEL00:06:081971

ECHOES FROM BANGLADESH FA 161

ECHOES FROM BANGLADESH

THE DEBEN BHATTACHARYA COLLECTION

Songs of love, life and the river / Chants d’amour, de vie et chants du fleuve

Songs of the refugees and freedom-fighters / Chants des combattants pour la liberté

INTRODUCTION

J’ai enregistré la musique que l’on peut écouter sur ces disques en trois occasions différentes. La première fois, c’était en 1954 à Calcutta et dans les rues de Varanasi, la seconde fois, pendant la guerre entre le Bangladesh et le Pakistan, en 1971 et la dernière fois, au Bangladesh en 1997. Bien que la musique de ces CDs provienne de ce qui est aujourd’hui le Bangladesh et était hier le Pakistan oriental, la plupart des enregistrements eurent lieu sur le sol indien. C’est pourquoi j’ai intitulé ce coffret «Echos du Bangladesh».Certaines des chansons qui se trouvent sur ces deux CDs racontent l’histoire des souffrances qu’a connu le Bengale pendant les deux périodes de sa partition: la première fût celle de l’implantation de l’Etat musulman pakistanais en 1947, fondée sur l’a priori que les Musulmans, minoritaires, ne pourraient coexister avec les Hindouistes après le départ des Britanniques en Inde. Puis de nouveau en 1971, quand les Pakistanais de l’Ouest refusèrent les résultats des élections démocratiques qui donnaient les Bengalis vainqueurs. Le gouvernement pakistanais lança alors contre les Bengalis désarmés un assaut brutal, dans ce qui était à l’époque appelé l’aile orientale du Pakistan. C’est dans un nouveau bain de sang que se manifesta la raison d’être du Pakistan. Les Pakistanais du Punjab parlant Urdu constituaient une simple minorité de la population totale du pays mais contrôlaient virtuellement l’ensemble du pays ainsi que l’armée. Allant à l’encontre de toute valeur démocratique, ils essayèrent d’imposer l’Urdu et leur bon-vouloir à l’aile orientale du pays.En février 1954, lorque j’arrivai en Inde avec mon tout premier magnétophone enregistreur, un semi-portable anglais appelé «GB Paul Kelee», je me retrouvai au beau milieu d’un festival de musique d’un grand intérêt historique. Un groupe de jeunes poètes, artistes et intellectuels bengalis de Calcutta s’étaient rassemblés et avaient réussi à passer le rideau de fer qui existait à la suite de la partition de l’Inde, au moment de l’indépendance en 1947. Ils avaient organisé un festival d’une semaine présentant les musiques de l’Est et de l’Ouest du Bengale, avec une attention particulière pour la musique populaire traditionnelle, dans un des parcs du centre de la ville.

L’histoire de l’Inde nous a prouvé plus d’une fois que, tandis que la politique et la religion ont été des facteurs de division, la musique, elle, a toujours été un facteur d’unité pour l’ensemble du sous-continent. Je n’étais donc pas surpris de voir les musiciens du Bengale oriental être accueillis par de chaleureux applaudissements par leur public de Calcutta, en l’occurence environ deux mille personnes.Pendant le festival, j’ai pu rencontrer des musiciens qui venaient des quatre coins du Bengale, mais il n’y en avait que quelques uns originaires du Bengale oriental, à cause, sans doute, des restrictions imposées sur les voyages. Parmi eux se trouvaient néanmoins trois géants de la tradition populaire bengalie, notamment les chanteurs aujourd’hui disparus Abbas-ud-din et Abdul Alim, aux côtés de Sohrab Hussain, qui grâce à Dieu, est encore parmi nous et bien vivant. En témoignage de mon respect pour ces deux grands chanteurs qui nous ont quittés, j’ai fait débuter le CD-1 (morceaux 1 &2) avec l’enregistrement de leurs voix, chantant des Bathiali, les chants du fleuve Bengale. Comme les fleuves eux-mêmes, ces chants originaires du Bengale divisé, ne peuvent se limiter aux frontières.En dehors des enregistrements de musiciens bengalis de l’Est et de l’Ouest que je réalisais pendant le Festival, j’étais le reste du temps dans les rues de Calcutta, les passant au peigne fin pour y découvrir des musiciens itinérants et trouvais là l’un des joyaux rares de la tradition populaire du Bengale oriental. Il s’agit d’une série de contes chantés intitulés «Maynamatir gan», provenant de la région de Mymensingh. Interprétés principalement par une vieille femme mécontente, ces contes étaient aussi chantés par un groupe de trois personnes qui avaient fuit vers Calcutta pendant la période des attaques lancées contre les minorités non-musulmanes du Bengale oriental, juste avant la partition, en 1946. Ce groupe avait parcouru les rues de Calcutta pendant huit longues années, depuis le moment où chacun avait quitté sa maison dans le Mymensingh, en espérant y retourner un jour (CD-1, morceau 3). Je devais vite me rendre compte que leur cas n’était pas isolé. En me promenant avec mon magnétophone, je fus amené à rencontrer un certain nombre de chanteurs de rue, en particulier des communautés Hindouistes originaires du Bengale oriental. Parfois, ils voyageaient en petits groupes, d’autres fois tout seul, explorant surtout les grandes villes du nord de l’Inde. C’était pour eux une manière de subvenir à leurs besoins, ainsi que d’assumer le fait d’être arrachés à leur mère-patrie. A Varanasi, j’ai pu enregistrer plusieurs chanteurs de rue du Bengale oriental. Il y avait parmi eux, un nommé Haripada Debnath qui chantait à la fois des chants traditionnels ainsi que des chansons de sa propre composition accompagnées par des mélodies traditionnelles (CD-1, morceaux 5-7). Les chants d’Haripada Debnath reflètent ainsi le premier exode du Bengale oriental au moment de la partition de l’Inde.

La plupart de la musique présentée sur ces deux CDs vient cependant des camps de réfugiés du Bengale occidental. Elle fut enregistrée au moment du deuxième exode de ce qui était alors le Pakistan oriental, vers le Bengale occidental, en 1971. Ce ne fut d’abord que quelques flots de réfugiés qui se transformèrent rapidement en une espèce de déluge. On passa de quelques centaines à des milliers de réfugiés, puis à des dizaines de milliers, pour atteindre soixante mille réfugiés par jour. Ils furent environ dix millions à fuir en trois mois, tandis que l’armée pakistanaise de l’Ouest dévastait le Pakistan oriental, pillant, violant, torturant et tuant des civils sans armes - qu’ils fussent musulmans, hindouistes, chrétiens ou bouddhistes. Les premiers temps après leur arrivée, les réfugiés bengalis de l’est n’exprimaient à travers leurs chansons que peur et désespoir, comme après un choc. Mais alors que des mois de misère se succédaient les uns aux autres, avec des flots de réfugiés de plus en plus importants arrivant aux camps chaque jour, les nouvelles de la résistance opposée par les combattants de la libération, les Mukti Bahini, se firent aussi plus présentes. Avec cette lueur d’espoir revint la dignité, et la résistance grandit. Des chansons comme celles présentées sur le CD-2, souvent composées et interprétées par des musiciens amateurs, eurent un impact immense sur la vie et le moral des réfugiés, comme sur celui des combattants de la liberté. En écoutant ces chants, on comprend exactement la raison pour laquelle les Pakistanais avaient blessé les Bengali au plus profond, et en particulier les Musulmans bengalis. Ils avaient abusé de leur confiance et de leur hospitalité au nom de Dieu, de l’Islam et du Pakistan.J’ai enregistré les trois derniers morceaux du CD-1 au Bangladesh en septembre 1997 au cours d’une visite effectuée comme invité du Musée de La Guerre de Libération. J’avais été convié à parler de mon expérience et à faire entendre mes enregistrements des chants des combattants de la libération à la rencontre organisée à Dhaka. La réaction du public à l’écoute de ces chants, après vingt-cinq ans d’indépendance, me fit comprendre que, n’avait été le pouvoir unificateur de la langue bengalie, de sa poésie et de sa musique, le Bangladesh aurait encore très bien pu être l’aile orientale du Pakistan, une simple province vassale. Des chansons tirées d’une tradition vivante comme celles du Bengale -Est ou Ouest- ont une influence vitale sur le cours des évènements. Au début de ce siècle, les Bengalis avaient usé avec succès de leur chansons dépeignant les injustices politiques pour soulever une colère populaire contre les Britanniques qui tentaient de diviser le Bengale. De la même manière, les chants des combattants de la liberté du Bangladesh reprirent une tradition ancestrale au Bengale en général - celle de guerriers et de chanteurs s’unissant dans leur combat pour la liberté et la paix.

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

Remerciements

Je tiens à exprimer toute ma reconnaissance à Mr Mustafa Zaman Abbasi, fils du très regretté Abbas-ud-din et à Mr Asghar Alim, fils du très regretté Abdul Alim, pour m’avoir accordé l’autorisation de reproduire les chansons interprétées par leur père respectif, que j’avais eu le privilège d’enregistrer au Banga Samskriti Sammelan à Calcutta en 1954 (CD-1, morceaux 1&2). Mes très sincères remerciements vont aussi à Maggie Doherty pour son aide à la production de cet album.Je tiens également à préciser que certains morceaux présents sur ces deux CD étaient parus sur des disques vinyles dès 1972, peu après l’indépendance du Bangladesh, ainsi que sur des cassettes audio destinées aux circuits éducatifs. Ce coffret est le premier de ma collection CD à représenter le Bangladesh.

D.B.

© GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 1998.

LA MUSIQUE ET LES INSTRUMENTS

Situé au Nord-Est du sous continent indien, en face du Golfe du Bengale, le Bangladesh est la moitié orientale du territoire où l’on parle Bengali, l’autre moitié étant l’Etat du Bengale occidental de la république indienne. Aujourd’hui, le Bangladesh et le Bengale occidental rassemblent une population de 200 millions de Bengalis. Pays traversé par un fleuve, le Bangladesh comme le Bengale occidental, est renommé pour ses paysages verdoyants et généreux de rizières et de champs de jute, relevés par les hauts cocotiers et les palmiers, les arbres plantains très feuillus et les grands manguiers verts. Fiers de leur pays et de son héritage poétique et littéraire, les Bengalis sont en général très sensibles aux chants traditionnels qui décrivent la vie dans leur région de delta fertile et le long des grands fleuves qui traversent le pays pour se jeter dans le Golfe du Bengale.La musique traditionnelle du sous-continent indien se présente sous deux formes distinctes, comme c’est le cas d’ailleurs pour le Bangladesh. L’une de ces formes est basée sur le style classique du système de Raga-Tala, destiné à ceux qui sont instruits de l’art musical, aussi bien pour l’exécution que pour l’écoute. L’autre, appelé «Deshi» (de la terre), appartient à la tradition populaire et s’intéresse à la vie de tous les jours; c’est la thématique de ce CD.

Il y a dans la tradition populaire du Bangladesh des chansons écrites même pour célébrer un jardin potager, ce qui est compréhensible étant donnée l’importance de chaque parcelle de terre pour un peuple dont le pays, comme le Bangladesh, a l’une des densités de population les plus élevées au monde. Les paroles de la chanson suivante, par exemple, décrivent les parcelles de légumes du potager avec un amour qu’on ne retrouverait habituellement que pour célébrer un jardin de roses:«Derrière ma petite hutte, j’ai planté mon jardinDe piments. Ils reflètent la couleur du cielEt chaque bouquet est une parure à la plante...»Le chanteur de Rangpur qui chantait une chanson aussi peu prétentieuse sur son potager, pouvait également chanter, quand il y était provoqué: «O Bengalis, ne laissez pas l’ennemi s’attarder sur votre terre,Ceux qui sont capables de vous battre, alors qu’il partagent votre nourriture,Ne les pardonnez pas..»Le Bangladesh est un réservoir de chants populaires religieux ou profanes. Ils sont de différents types, Bhatiali, Sari, Baul et bien d’autres encore. Les Bahtiali (CD-1, morceaux 1 et 2) sont chantés en solo et reflètent l’appel à la contemplation qu’évoquent le fleuve et son ressac, incitant la voix à atteindre les plus hautes tonalités. Les Sari, au contraire, sont chantés en groupe et illustrent la force de l’unité. Ils sont chantés pendant les courses de bateaux ou autres occasions similaires.

Les chants Baul (CD-2, morceaux 12 et 14) peuvent être chantés par un Musulman ou un Hindou puisque, dans sa recherche de Dieu, le Baul véritable est un individualiste forcené qui se détourne de tout système religieux organisé. Pour lui, un système est un obstacle aussi menaçant qu’un barrage routier:« La route vers toi est bloquéePar les temples et les mosquées.J’entends ton appel, oh mon Dieu, Mais je ne peux avancer...Les professeurs, les prêcheurs et les prophètes me barrent la route...»(Madan Baul, 19ème siècle). La majorité de la population du Bangladesh vit dans des villages, comme on peut en juger par les paroles des chansons qui décrivent leur mode de vie. Les instruments traditionnels dont ils se servent pour accompagner leurs chants sont pour la plupart faits de matériaux aisément disponibles dans leur entourage. Par exemple, le luth à quatre cordes qui a une caisse recouverte de peau, est creusé dans le bois de l’arbre à pain. Les arbres à pain sont très courants dans les villages du Bangladesh. Encore vert, le fruit est cuit comme un légume, et lorsqu’il arrive à maturité, il est mangé comme un fruit. Un certain luth a aussi cinq cordes sympathiques, et s’appelle le Sworaj, un autre, également à cinq cordes, mais qui ne sont pas sympathiques, s’appelle le Dotara. Les deux sont pincés avec des plectres faits de corne de buffle. Il existe aussi un instrument à résonance avec une seule corde appelé Ektara.

Il y ensuite les Banshis, des flûtes transversales à l’embout gonflé, qui comportent souvent six trous. De petites cymbales et des claquettes de bois appelées Kath-kartals sont jouées pour marquer le rythme. On joue des Kath-kartals comme des castagnettes. En plus de ces instruments, qui sont strictement traditionnels, on rencontre aussi les paires de tambours appelées Tabla, accompagnant habituellement les Ragas, sur des chansons traditionnelles. Enfin, comme en Inde, l’harmonium est très apprécié au Bangladesh.

CD-1

Chants d’amour, de la vie et chants du fleuve

(voir introduction p. 7 pour la description des instruments).

1. Bhatial ganger naiya. Un chant du fleuve à propos des amants séparés, sur une mélodie Bhatiali. La chanson exprime les sentiments d’une jeune fille amoureuse avec ses propres mots:»J’ai été délaissée et n’ai plus que mes larmes pour contempler ma maison, sur les berges lointaines du fleuve. Mes larmes s’écoulent avec le flot de la rivière. Comment peut-il vivre sans moi, m’abandonner aux tigres de la forêt? S’il me quitte encore une fois, je me noyerai avec une pierre attachée à mon cou. Il pourra alors me transporter sur un lit de bambou, vers ma dernière couche de vierge». Chantée par le défunt Abbas-ud-din, de Dhaka, et accompagné par un Dotara, des Tablas et un harmonium, elle fût enregistrée pendant le All Bengal Music Festival organisé par Banga Samskriti Sammelan, à Calcutta. Février 1954. 4’45.

2. Ujan ganger naiya. Un chant du fleuve à propos de la vie solitaire d’un pêcheur, sur les vastes rivières du Bangladesh, chanté sur une mélodie Bhatiali. Il dit : «O pêcheur, allant contre-courant, peux-tu me dire jusqu’où s’étend la rivière, alors qu’elle efface les rives du fleuve? J’attache mon bateau à une rive du fleuve en espérant retrouver mon amour qui m’a quitté. J’ai entendu dire que le fleuve coule vers la mer, mais à quelle mer se mêlent mes larmes? Les fleurs sauvages se languissent de cette rive inconnue». Chanté par le feu Abdul Alim, de Dhaka, et accompagné par un Dotara, des Tablas et un harmonium, il fût enregistré pendant le All Bengal Music Festival organisé par Banga Samskriti Sammelan, à Calcutta. Février 1954. 5’40.

3. Maynamatir gan. C’est un court extrait d’une série de contes intitulée «Les Chansons de Maynamali». Bien que rarement joués aujourd’hui, ils étaient autrefois très appréciés dans le Dinajpur, le Rangpur et le Mymensingh. Cet enregistrement raconte l’histoire d’une certaine princesse Maynamali et de la relation extra-conjugale qu’elle souhaite conserver quand meurt son mari. Pour arriver à ses fins, elle pense à éloigner son fils, le jeune chef de la principauté, et à l’envoyer sur les routes de l’ascèse, à la recherche de Dieu et de la spiritualité. Le Prince, marié, s’oppose d’abord à ce projet car il veut rester près de son épouse, puis finalement se rend aux volontés de sa mère. Ce passage de la chanson traduit la discussion entre la mère et le fils. Il est chanté par un groupe de chanteurs de rue, menés par une femme du Mymensingh qui ne voulu pas dévoiler les noms des musiciens. Depuis la période du premier exode des minorités du Pakistan oriental en 1946-47, ce groupe avait gagné sa vie en se produisant dans les rues de Calcutta. Les chanteurs s’accompagnaient du luth Dotara, de la flûte transversale de bambou et des cymbales pour les doigts. En plus de ces instruments, ils jouaient aussi d’un tambour que l’on pince, appelé le Anandalahari, qui marque le rythme avec des variations de tons. Enregistré à Calcutta en Février 1954. 4’15.

4. Ulta desh. Un chant presque surréaliste commençant par ces mots «Ulta desh» qui veulent dire «terre renversée». Il appartient au genre des chants philosophiques appelés «ulta Baul». Les Bauls sont des poètes-chanteurs itinérants du Bengale, allant de village en village (voir introduction). Ils sont issus des sociétés hindouiste et musulmane. Les paroles de la chansons racontent : «Où peut-on voir une terre aussi renversée? Les habitants y vivent la tête sur terre et les pieds au ciel. Les eaux des rivières de ce pays coulent à contre-courant et le ciel demeure au pied de la rivière, tandis que l’air souffle librement à travers. Les gens qui habitent ce pays ne mangent pas avec leur bouche, ni ne respirent à travers leurs narines. Ils ne se débarrassent pas du trop-plein du corps, mais au contraire l’absorbe. (Le poète) Sharat dit que je me réjouis de vivre dans un pays d’obscurité, où le soleil et la lune sont immobiles». Chanté par deux chanteurs de rue à Varanasi, s’accompagnant de l’Ektera et des cymbales pour doigts. Les deux chanteurs, Ramananda et Raidvani étaient venus de Comilla pendant l’exode des minorités en 1946-47. Enregistré à Varanasi en 1954. 3’50.

5. Ashole binash hoila. Chanson traditionnelle qui dit:»Que puis-je faire, mon coeur, j’ai perdu mon capital? Avec tout mon investissement qui tenait dans mon coeur, j’ai été l’objet de fourberies dans une terre étrangère. Ils m’ont volé tout ce que j’avais et j’ai des dettes dans ce pays étranger. Ceux qui m’accompagnaient sont partis, je n’ai plus que des étrangers devant les yeux, et personne de mon pays à moi». Sur un plan philosophique, cette chanson exprime la recherche de l’âme pour sa véritable résidence, mais dans le cas présent le chanteur parle, avec les mêmes mots des difficultés rencontrées pendant l’exil. Elle est chantée par Haripada Debnath, un réfugié de Comilla depuis1946. Haripada vivait à Varanasi et gagnait sa vie comme chanteur de rue et homme à tout faire. Il avait fabriqué son propre Dotara avec lequel il s’accompagnait. La chanson a été enregistrée à Varanasi en 1954. 4’30.

6. Sharanarthir gan. Chanson d’un réfugié qui dit:»Oh résidents de ma ville, s’il vous plaît, ne vous éloignez pas sans écouter mes humbles paroles. Mendiant dans la rue, je suis sans un sou. Comme un homme perdu, je vais de porte en porte depuis que notre pays a été divisé, depuis que les femmes ont été enlevées et retenues sans raison. Les bandits faisaient la loi dans la rue. Bien que nos cœurs se fussent rempli de joie quand Nehru nous a invité en Inde, nous sommes toujours des étrangers sur cette terre...» Ecrit et chanté par Haripada Debnath, qui s’accompagnait sur le Dotara, comme ci-dessus. Enregistrée à Varanasi, en 1954. 4’40.

7. Dotara. Joué par le chanteur Haripada Debnath et enregistré à Varanasi en 1954, ce morceau représente un mélange de deux formes mélodiques, le «Baul» et le «Bhatiali». 7’05.

8. Ami tomay bhalobeshe. «En t’aimant, je me suis vidé. Je n’ai rien à offrir que l’amour, en retour de la souffrance. Quand l’amour dure toute la vie, l’amant est capable d’offrir toute sa vie...» La chanson est écrite et chantée par Muhammad Jala Dewan de Comilla et commence par une introduction parlée présentant le chanteur lui-même et la chanson, exécutée sur une mélodie traditionnelle. La chanson est accompagnée par un Dotara, une flûte bambou, un Dhol (tambour en forme de tonneau), des cymbales pour doigts et un harmonium. Enregistrée à Dhaka. Août 1997. 5’30.

9. Manush banaichhe Allah.?«Allah a fait venir l’être humain pour la seule raison de l’amour... Allah a créé tant d’espèces mais aucune n’a une quelconque idée de l’essence de l’amour... Les Ecritures parlent de l’Homme en disant qu’il a été formé au plus profond de la nuit, se révélant au monde par la propre lumière de Dieu...» C’est une vieille chanson populaire,chantée par Muhammad Kamal Dewan de Dhaka. Tout comme le morceau précédent, la chanson commence après que le chanteur s’est présenté. Il est accompagné par les mêmes instruments que ceux décrits ci-dessus. Enregistré à Dhaka. Août 1997. 4’20.

10. Murshidi. Une chanson de dévotion, dédicacée au Murshid, le Sufi spirituel, guide et chef philosophique. D’après le chanteur Muhammmad Suruj Dewan de Dhaka, qui présente la chanson et se présente lui-même, cette chanson a 300 ans. Les paroles sont: « Je n’ai pas besoin de la richesse, O tout petit, emmène-moi avec toi lorsque tu pars. Ne porte pas mon corps à la crémation, ne le jette pas dans le fleuve lorsque je mourrai, mais répète le nom de mon Maître et baigne mon corps de l’eau dans laquelle il a lavé ses pieds. Ne coupe pas de bambou à la racine pour supporter mon corps, mais sers-toi de la canne de mon Maître. Je n’ai pas besoin d’un linceul de coton neuf, mais enveloppe-moi plutôt dans la chemise usée de mon Maître...» La chanson est accompagnée par les instruments qui sont décrits dans le morceau n°8 (voir Guru tumi ei golar-i har, CD-2, morceau 10. De plus, les paroles et l’esprit de cette chanson renvoient à une chanson de dévotion populaire hindoue du 15ème siècle, à propos de l’amour de Rhada pour Krishna). Enregistrée à Dhaka. Août 1997. 7’50.

CD-2

CHANTS DES REFUGIES ET DES COMBATTANTS POUR LA LIBERATION

(voir introduction pour la description des instruments).

1. Nijer paye nije hete chal. « Marchez de vos propres pieds, O frères bengalis, le Mujibar (père de la nation), en armes, nous appelle. Les Bengalis n’ont pas peur des soldats de Khan (le Général Yayah Khan, dictateur militaire du Pakistan au moment de la guerre au Bangladesh en 1971). Les voleurs qui viennent de l’Ouest (les Punjabis et Sindhis du Pakistan occidental) en cette terre des Bengalis transforment notre sang en eau morte. Au nom de l’Islam, ils nous sucent de toute part, tandis que le feu bouillone dans nos ventres....Les Bengalis sont déterminés à construire leur propre nation et refusent de vivre dans la misère...» Chanson composée et chantée impromptu sur les lieux par un Kabiyal (sorte de poète-chanteur) appelé Muhammad Safi de Sandwip, Chittagong. Sans accompagnement. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Octobre 1971. 4’45.

2. Koiona, koiona, bandhure. «O mes amis, ne parlez pas de mon malheur alors que ma jeunessse solitaire se consumme, dévorant comme un feu chaque mois de l’année. Quand l’eau de la mer commence à bouillir au mois de Phalgun (Février-Mars), mon jeune désir se réveille avec espoir. Après Chaitra, lorsque les mangues sont mûres sur les arbres au mois de Baishakh (avril-mai), l’abeille amoureuse bourdonne près de ma chambre. En Ashadh (juin-juillet), lorsque les pluies tombent averse et que tout le monde sort pour prendre une douche, je reste à l’intérieur et je pleure.A la fin de Shravan, au mois de Bhadra (août-septembre), lorsque les grands fruits des palmiers sont mûrs sur les arbres, comment pourrais-je, en mon mahleur, les manger! Au mois d’Ashwin (septembre-octobre), lorsque la rivière est froide et que le pêcheur chante son amour, je l’entends de ma maison et j’ai envie de lui demander de s’envoler vers mon amour et de me rapporter de ses nouvelles. Combien de temps pourrai-je encore attendre son retour et pleurer?...» Intitulée Baramasya, cette chanson est dédiée aux saisons et aux amants séparés. Elle est chantée sans accompagnement par Muhammad Safi de Sandwip, Chittagong, comme ci-dessus. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Octobre 1971. 4’10.

3. Surja udala lal mari. «Le soleil s’est levé dans un éclat rouge alors que mon bien-aimé me quittait, me déchirant comme avec un missile. Je n’ai personne à qui parler de mes tourments, de mon coeur qui me tient éveillée et pleure toute la nuit. Comme je parle de mon bien-aimé, des larmes s’écoulent de mes yeux comme la rivière Kamaphuli, avec des vagues qui soulèvent ma poitrine. Chanté sans accompagnement, ce chant d’amour est interprété par Muhamad Safi de Sandwip, comme ci-dessus. Enregistré à Calcutta. Octobre 1971. 3’18.

4. Choto choto dheu. «En descendant des collines de Lusai, la rivière Kamaphuli s’écoule en soulevant de douces vaguelettes dans son flot. Le long d’une rive s’étendent de champs verdoyants, sur l’autre des villages et des villes. Accompagnées du chant des oiseaux, les femmes viennent à la rivière chercher de l’eau. Or il était une fois une jeune fille qui avait perdu sa boucle d’oreille dans l’eau, et ainsi elle fut appelée Kamaphuli, la rivière de la boucle-d’oreille». Chanson de la rivière Kamaphuli. Le texte, chanté sur une mélodie traditionnelle est écrit et interprété par Malay Gosh-dastidar de Chittagogng. La chanson est accompagnée par un Dotara et des Tablas. Enregistrée dans un camp de réfugiés à Kalyani, Bengale occidental. Octobre 1971. 5’30.

5. Malkha Banu. « Malkha Banu a sept frères mais le malheureux Monu Mla n’en a aucun. Comment Monu ira-t-il à la maison de Malkha Banu, qui est entourée de marais? Le roulement des tambours Dhols et la musique de Shahnai (flûte bengalie à la tonalité très aigüe) font trembler le coeur de Monu d’appréhension. Monu Mla vient d’un pays entouré de mers et Malkha doit l’épouser». Chanson traditionnelle de Chittagong. Elle est chantée par Mangal Barua de Chittagong et est accompagnée par un Dotara et des Tablas. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Septembre 1971. 3’31.

6. Matir manush. «Nous avons droit à cette terre car nous y sommes nés. Nous sommes nés ici pour y vivre et y mourir. Nos corps sont faits de la même substance que cette terre et nous nous battrons pour la défendre, afin de pouvoir lui abandonner nos corps». Chanson patriotique écrite et composée sur une mélodie traditionnelle par Ramesh Shill et interprétée par Mangal barua de Chittagong. Elle est accompagnée par un Dotara et des tablas. Enregistré à Calcutta. Septembre 1971. 4’00.

7. Janmabhumi janani. «O mère patrie, mon coeur pleure de chagrin, comme si tu étais ma mère. Tu as comblé nos vies en nous donnant tout ce que tu avais à offrir, mais maintenant, où es-tu, et où somme nous? Ils t’ont volée et encerclée, ils t’ont dépouillée de tout ce que tu avais, faisant de toi une mendiante. Ils n’ont jamais reçu d’amour de leur mère, et ne savent pas la valeur d’une mère». Chanson patriotique interprétée poar Chitta Bhulya de Noakhali. Elle est accompagnée par un Dotara et des Tablas. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Septembre 1971. 2’45.

8. Tomar Bangla amar Bangla. « Gloire au Bengale, qui nous appartient à toi et à moi. Il n’y a pas de différence entre les Hindouistes, les Musulmans et les Chrétiens dans ce Bengale où nous habitons. Le Mujibar qui nous guide est le père du Bengale. Saluons-le...» Chantée par un groupe d’orphelins réfugiés de l’orphelinat de khelaghar à Kalyani. Bengale occidental. Octobre 1971. 1’50.

9. Pal tule de. « Lève la voile, Robin, lève la voile du bateau pour cette douce et frémissante brise. La lumière du jour s’estompte dans le ciel du soir...» Un chant du fleuve, interprété par Gobinda Bagdi, âgé de 9 ans. C’est un orphelin du Pakistan oriental. Le chant a été enregistré dans le même orphelinat que mentionné ci-dessus, appelé Khelagar, à Kalyani. Octobre 1971. 1’50.

10. Guru tumi amar ei golar-i har. « Maître, tu es le collier autour de mon cou, le don de ma vie, paré de qualités sans fin. Mon amour des atours exprime ma dévotion pour toi, je porte des boucles d’oreilles pour entendre résonner ton nom et ces anneaux à mon nez pour inhaler tes parfums. Comme la bague qui pare le doigt, tu es une parure à mon coeur». Appelée Gurutatva dans la tradition hindouiste, cette chanson exprime la dévotion au maître spirituel, ou guru, comme on l’appelle au Bengale (voir le Murshidi, le Sufi de la chanson de dévotion sur le CD-1, morceau 10). Ecrite et composée sur une mélodie traditionnelle par Balaram Sharma de Jessore, elle fut enregistrée au camp de réfugiés de Kalyani. Octobre 1971. 2 ’35.

11. Mon tumi Darshanate gelena. «Mon coeur, tu n’a pas pu rendre visite à Darshana. Tu n’a fait qu’attendre à Chuadanga, sans reconnaître Arangghata...» Ecrite et composée sur une mélodie traditionnelle par Balaram Sharma de Jessore, comme ci-dessus, cette chanson consiste en une évocation de noms de villages et de villes des deux parties du Bengale, Est et Ouest, par lesquels le chanteur est passé pour arriver au camp de réfugiés de Kalyani au Bengale occidental. La chanson évoque également les lieux que le chanteur aurait aimé pouvoir découvrir mais où il n’a pu s’arréter. La chanson a été enregistrée au camp de réfugiés de Kalyani. Octobre 1971. 3’05.

12. Mon pabaner naiya. « O navigateur de mon coeur tourmenté, comment vas-tu faire avancer le bateau de mon attachement, plein de désir, de beauté et d’amour? Seuls ceux qui sont fin connaisseurs de l’art des sentiments peuvent naviguer sur la rivière des émotions. A emmener ton embarcation sur les eaux du désir, tu couleras certainement». Cette chanson Baul (voir introductioin pp 4&5) est écrite et chantée par Baul Torap Ali Shah de Jessore, sur une mélodie Baul, avec pour accompagnement le luth Sworaj. La chanson est aussi accompagnée par un ensemble de petites cloches appelé le Ghunghur. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Novembre 1971. 3’35.

13. Hai Sheikh Mujibar. Chanson de louanges adressée au Mujibar Rahman, le père de la nation. Bien que le Sheikh fusse à l’époque emprisonné au Bengale occidental, à plus de 2000 kilomètres, son nom était souvent associé à celui de Mukti Bahini, l’armée de libération pendant la guerre avec le Pakistan. La chanson commence par ces mots : «Sheikh Mujibar a enchanté tout le monde. En dérobant le coeur de chacun il est venu libérer le Bengale et mener l’armée de libération». Elle se poursuit par une comparaison entre le Sheikh et les rois légendaires de l’histoire du Bengale. Chantée par Baul Torap Ali Shah de Jessore, comme dans le morceau ci-dessus n°12, qui s’accompagne du Sworaj. Le rythme est marqué par un ensemble de cloches de fonte appelé ghunghur et une paire de claquettes en bois apellée Kath-kartal. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Novembre 1971. 6’35.

14. Ekbar phire chao-he praneshwar. «Pour une fois, tourne tes yeux vers moi, O Seigneur de ma vie. Ton nom est constamment sur mes lèvres, alors que je le répète en me servant de ma bouche comme d’un rosaire. Combien de temps me tromperas-tu, toi qui m’aveugle d’espoir? Ma vie est vide sans toi et je n’attends que de laver tes pieds de mes larmes.» Une chanson Baul écrite et chantée par Baul Torap Ali Shah de Jessore, comme dans le morceau ci-dessus, n°12. Elle est accompagnée par le Sworaj et l’ensemble de cloches apellé Ghunghur. Enregistrée à Calcutta. Novembre 1971. 6’00.

Enregistrements, photographies et textesDEBEN BHATTACHARYA

Adaptation française Anika Scherrer

© GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 1998.

english notes

FOREWORD

I recorded the music reproduced in this set of two CDs on three separate occasions. The first time was in 1954 in Calcutta and in the streets of Varanasi, the second time during the Bangladesh war with Pakistan in 1971 and finally in Bangladesh itself in 1997. Although the music on the CDs originally comes from today’s Bangladesh which was yesterday’s East Pakistan, most of the music was recorded on Indian soil. Therefore I am calling the CD set «Echoes from Bangladesh».Some of the songs on these two CDs tell the story of the country’s sufferings through twofold partition of Bengal : once to install the Islamic State of Pakistan in 1947 with the assumption that the Muslims as a minority could not coexist with the Hindus when the British left India. Then again in December 1971, following West Pakistan’s refusal to accept the result of a democratic election in which the Bengalis were victorious. The Government of Pakistan launched a brutal assault on the unarmed Bengalis in its Eastern wing known as East Pakistan at the time. The reason for the birth of Pakistan repeated itself, in renewed blood letting. The Urdu speaking Pakistanis of Punjab who consitituted only a minority of the country’s population were in virtual control of the country and its Army. They tried to impose Urdu and their will on the eastern wing of the country against all democratic values.In February 1954 when I landed in India with my very first tape-recorder, a British made semi-portable called «GB Paul Kelee», I found myself in the middle of a music festival of great historical interest. A group of young Bengali poets, artists and intellectuals from Calcutta had got together and managed to break through the iron curtain caused by the partition of India during independence in 1947. They held a week long festival of music from East and West Bengal, with emphasis on folk traditions, in a public park at the centre of the city. The history of India has shown us time and again that while politics and religion have divided the people, music has held the vast population of the sub-continent together. There are great Dhrupad singers among the Muslim musicians of India although Dhrupad represents Hindu religious sentiments.

I was therefore not surprised to see the musicians from East Bengal being received with thunderous applause by the two thousand strong Calcutta audience at the festival.During the festival I met musicians from every corner of West Bengal but there were only a select few from East Bengal, owing, possibly to travel restrictions. Among them, however, there were three giants of Bengali folk traditions, namely, the late singers Abbas-ud-din and Abdul Alim besides Sohrab Hussain, who, thank God, is still very much with us. As an expression of my respect for those two departed great singers of the past, I am starting CD-1 (items 1 & 2) with their voices, singing Bhatiali, the river songs of Bengal. Like the rivers themselves, the river songs of the partitioned Bengal, cannot be held back by the frontier control.Besides recording the musicians from East and West Bengal during the Festival, at off hours I was combing the streets of Calcutta for itinerant musicians and there I found a rare jewel of East Bengal’s folk tradition. It is part of a series of sung tales entitled «Maynamatir gan» from the district of Mymensingh. Led by a wirey looking elderly woman this was sung by a group of three who had fled to Calcutta during the pre-partition attacks on the non-Muslim minorities of East Bengal in 1946. For eight long years this group had been roaming the streets of Calcutta since they had fled from their home in Mymensingh, still hoping to return one day (cf. CD-1, item 3). I was to discover soon, however, that this was not an isolated case. As I began to travel with my tape-recorder I found a number of street singers, particularly from East Bengal’s Hindu communities. They moved sometimes in small groups and at other times on their own, exploring mostly the important cities of North India. This was one way of earning their living while trying to come to terms with being uprooted from their homeland.

In Varanasi I recorded several street singers from East Bengal. Among them was one named Haripada Debnath who sang both traditional songs as well as Iyrics composed by himself but set to traditional melodies (cf. CD-1, Items 5-7). Haripada Debnath’s song reflects the first exodus from East Bengal during the partition of India.Most of the music presented on these two CDs, however, comes from the refugee camps in West Bengal. It was recorded during the second exodus of refugees from the then East Pakistan, entering West Bengal in India in 1971. It started with trickles which soon turned into an avalanche. The numbers increased rapidly from a few hundred to a thousand, from a thousand to ten thousand, from ten thousand to sixty thousand a day. The total amounted to millions, reaching the figure of about ten million within three months as the West Pakistan Army rampaged through East Pakistan, looting, raping, torturing and killing unarmed civilians - Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Buddhists. During the early days of their arrival, the songs of the East Bengali refugees expressed fear and helplessness, following the initial shock. As months mounted upon months of misery, with vast numbers of new arrivals reaching the camp sites every day, reports about the resistance offered by the freedom fighters, the Mukti Bahini, came to be heard. With glimpses of hope, pride slowly returned and resistance increased. Songs, such as those presented on CD-2, often composed and sung by amateur musicians, had an enormous impact on the life and spirit of the refugees as well as the freedom fighters. While listening to these songs, it becomes clear where the Pakistani Army had hurt the Bengalis most, particularly the Muslims of East Bengal. They had abused trust and hospitality in the name of God, Islam and Pakistan.I recorded the last three items of CD-1 in Bangladesh in September 1997 during a visit as a guest of the Liberation War Museum.

I was invited to talk about my experience and replay the recordings of the freedom fighters’ songs at a gathering in Dhaka. The public reaction to those recordings, even after twenty-five years of independence made me realise that if it were not for the binding power of the Bengali language, its poetry and music, Bangladesh might still have remained the eastern wing, or a vassal state of Pakistan. Songs from a living tradition such as those of Bengal - East and West - play a vital role in influencing current events. Towards the beginning of this century, the Bengalis had successfully used their songs depicting political injustice to rouse public anger against the British attempt at dividing Bengal. Similarly, the songs of the freedom fighters of Bangladesh followed the age old tradition of Bengal as a whole - warriors and singers working together for freedom and peace.

DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

© GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 1998.

Acknowledgement

My grateful thanks are due to Mr. Mustafa Zaman Abbasi, son of the late Abbas-uddin and Mr. Asghar Alim, son of the late Abdul Alim, for permitting me to reproduce the songs sung by their fathers whom I had the privilege of recording at the Banga Samskriti Sammelan in Calcutta in 1954 (CD-1, items 1 & 2), My thanks are also due to Maggie Doherty for her help in the production of this album.This is also to acknowledge that some of the items presented on these two CDs appeared on LP records as early as 1972, soon after the independence of Bangladesh, as also on audiotapes for the Educational Media. These are the first CDs representing Bangladesh from my collection..

D.B.

MUSIC AND INSTRUMENTS

Situated in the northeast of the Indian subcontinent and facing the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh is the eastern half of the land of the Bengali speaking people, the other half being the State of West Bengal in the Republic of India. Currently Bangladesh and West Bengal combined have a population of over two hundred million Bengalis. A river country, Bangladesh, like West Bengal, is known for its lush green landscapes of endless paddy and jute fields, relieved by the towering heads of the coconut trees and date-palms, the massive fanlike foliage of the plantain and the great green mango trees. Proud of their country and its literary and poetic heritage which continues to flourish, the Bengalis as a whole are emotionally involved with their traditional songs which are descriptive of life in their fertile deltaic land and on the great rivers that flow across the country to the sea at the Bay of Bengal.The traditional music of the subcontinent of India consists of two distinct forms and the music of Bangladesh is no exception to this. One of the musical forms is based on the classical Raga-Tala system, intended for those who are educated in the art of music, either for performing or for listening. The other called «Deshi» (of the land) belongs to the popular or folk tradition and is involved with everyday life, which is the theme of this CD set.In the folk tradition of Bangladesh, there are songs even for a kitchen garden, as each inch of land means a lot to the people of a country like Bangladesh which has one of the highest population densities in the worid.

For instance, the words of the following song describe the vegetable patch of a kitchen-garden with such love as is normally bestowed upon a garden of roses :«Here behind my little hut, I have planted in my garden The chilli-peppers. Reflecting the colour of the skyThey adorn the plants bunch upon bunch...»The singer from Rangpur who could sing such a gentle unpretentious song about his kitchen garden, could sing the following song too when roused:«O Bengalis, do not let the enemy linger on your land. Those who can strike you, sharing your food,Do not forgive them...»Bangladesh is a storehouse of folk songs both religious and secular. They are presented as Bhatiali, Sari, Baul and in many other forms. Bhatiali (CD 1, Items 1 and 2) sung in solo voice, represents the contemplative nature of the river with its ebb and tide, provoking the soaring flight of the voice to its very limits. Sari, on the other hand, is intended for group singing, representing the strength of togetherness. It is sung during boat races and similar occasions. The Baul songs (CD-2, Items 12 and 14) can be sung by a Hindu or Muslim Baul since in his search for God, the true Baul is a determined individualist with a strong dislike of any organised religious system. The system stands in his way as threateningly as a road-block : «The road to you is blocked By temples and mosques.I hear your call, my lord, But I cannot advance...

Teachers, preachers and prophets bar my way...»(Madan Baul, 19th cent.)The majority of the population of Bangladesh live in the villages as can be judged from the words of their songs which are descriptive of their lifestyle. The traditional instruments they use for accompanying their songs are mostly based on material which is easily available in the countryside. For example, the four-stringed lute with a skin-covered belly which is carved out of jack-fruit wood. Jack-fruit trees are very common in the villages of Bangladesh. The fruit, when green, is cooked as a vegetable and when ripe, it is eaten as a fruit. One of the lutes also has five sympathetic strings and is called Sworaj and the other, without sympathetic strings, is the Dotara. Both the lutes are plucked with plectrums made from buffalo horns. In addition to the Dotara, there is a single-stringed drone instrument called Ektara. Then there are the Banshis, the transverse and the end-blown bamboo flutes, often with six finger-holes. Small cymbals and the wooden clappers called Kath-kartals are played to provide the rhythm. The Kath-kartals are played like castanets. In addition to these instruments which are strictly of folk origin, a pair of drums called the Tabla, which are commonly employed for accompanying Ragas are also played at times to accompany traditional folk songs. And then, of course, as in India, the Harmonium is also very popular in Bangladesh.

CD 1

Songs of love, life and the river

(See introduction p 23 for description of instruments)

1. Bhatial ganger naiya. A river song on separated lovers with a Bhatiali melody. The song expresses the feelings of a girl in love in her own words, saying «I am left behind only to shed tears looking toward my home on the far away shores of the river. My tears flow along with the water of the river. How can he live without me, abandoning me to the tigers of the forest? If he leaves me once again, I shall drown myself with a weight around my neck. He can then carry me on a bamboo bier, in my final bridal bed.» Sung by the late Abbas-ud-din, from Dhaka, and accompanied by Dotara, Tabla and harmonium, it was recorded during the All Bengal Music Festival organised by Banga Samskriti Sammelan, Calcutta, in February, 1954. 4.45 mins.

2. Ujan ganger naiya. A river song about the solitary life of a boatman on the vast rivers of Bangladesh, sung with a Bhatiali melody. It says: O boatman against the current, can you tell me how far away has the river stretched itself, washing away the river banks as it has gone? I tie my boat on a broken down bank of the river hoping to find my gone away love. I have heard the river flows to the sea, but in which sea do my tears mingle ? The wild flowers cry for that unknown shore.» Sung by the late Abdul Alim, from Dhaka, and accompanied by Dotara, Tabla and harmonium, it was recorded during the All Bengal Music Festival organised by Banga Samskriti Sammelan, Calcutta, in February, 1954. 5.40 mins.

3. Maynamatir gan. This is a brief extract from a serialised sung-tale entitled the «Songs of Maynamati». Though rarely performed these days, it used to be popular in Dinajpur, Rangpur and Mymensingh. This recording tells the story of a certain princess Maynamati and her extra-marital relationship which she wanted to continue undisturbed when her husband died. In order to fulfill her plan she plotted to send away her son, the young ruler of the principality, as an ascetic in search of God and spirituality. But the Prince was married and put up a resistance against leaving his wife although finally he complied with his mother’s wishes. This section of the song represents the argument between the mother and the son. It was sung by a group of street singers, led by an elderly woman from Mymensingh who did not want to give the musicians’ names. Since the first exodus of the minorities from East Pakistan during 1946-1947, this group had been earning their living as street singers in Calcutta. The singers accompanied themselves on the lute Dotara, the transverse bamboo flute and finger-cymbals. In addition to these instruments, they also played a plucking drum called the Anandalahari which provided the rhythm with pitch variations. It was recorded in Calcutta in February, 1954. 4.15 mins.

4. Ulta desh. Almost surrealistic, this song starting with the words «Ulta desh», meaning an upside down land, belongs to a type of philosophical songs called «ulta Baul». The Bauls are the itinerant poet-singers of village Bengal (cf. Introduction) and come from both the Hindu and the Muslim societies. The words of the song say «Where can you find such an upside down land ? The inhabitants live with their heads on the earth and their feet in the air. The water of the rivers of this land flows upstream and the sky lies at the bottom of the river while the air blows freely through it. The people of this land do not eat with their mouth, nor breathe through their nose. They do not discharge the body’s waste matter but absorb it. [The poet] «Sharat says I live in that land of darkness with joy where the Sun and the Moon are motionless.» It was sung by a couple of street-singers in Varanasi, accompanying themselves on the Ektara and the finger-cymbals. Named Ramananda and Raidhvani, the singers came from Comilla during the exodus of the minorities in 1946-47 from East Pakistan. Recorded in Varanasi in 1954. 3.50 mins.

5. Ashole binash hoila. A traditional song which says : «what can I do, my heart, I have lost all my capital ? With the total investment held in my hand, I have been a target of cheats in a foreign land. They have snatched away all I had and I am in debt in an unfamiliar land. Those who were with me are gone, only strangers block my vision, with no one from my own land.» Philosophically, the song expresses the soul’s search for its true home but in the present case the singer speaks of his own problem as an exile through these same words. It was sung by Haripada Debnath, a refugee from Comilla since 1946. Haripada lived in Varanasi and earned his living as a street singer and a handyman. He made his own Dotara with which he accompanied himself. The song was recorded in Varanasi in 1954. 4.30 mins.

6. Sharanarthir gan. Song of a refugee, it says : «O dwellers of this town, please don’t go away without listening to my humble words. A beggar in the street, I am without a penny. Like a man lost, I move from door to door since our country was divided, women abducted and men held without reason. Gangsters ruled the streets. Although our hearts filled with joy when Nehru brought us to India, we are still strangers in this land...» Written and sung by Haripada Debnath accompanying himself on the Dotara, as above. Recorded in Varanasi, 1954. 4.40 mins.

7. Dotara. Played by the above singer Haripada Debnath and recorded in Varanasi in 1954, this piece represents a blending of two melodic forms «Baul» and «Bhatiali» . 7.05 mins.

8. Ami tomay bhalobeshe. «Loving you, I have emptied myself. I have nothing left to offer but love in return for pain. When love is life long, the lover is able to offer all of life...» The song, written and sung by Muhammad Jalal Dewan of Comilla begins with a spoken introduction by the singer about himself and the song which is set to a traditional folk melody. The song is accompanied by a Dotara, bamboo flute, Dhol (barrel drum), finger-cymbals and a harmonium. Recorded in Dhaka, August, 1997. 5.30 mins.

9. Manush banaichhe Allah. «AIIah has brought forth the human being for the cause of love... So many species are formed by Allah but none has a clue about the essence of love... The scriptures speak of Man being shaped in the deep of the night, appearing in the world from God’s own light...» An old folk song, it is sung by Muhammad Kamal Dewan of Dhaka. Just as the previous item, the song starts after the singer has introduced himself. It is accompanied by the instruments as described above. Recorded in Dhaka, August 1997. 4.20 mins.

10. Murshidi. A devotional song dedicated to the Murshid, the Sufi spiritual and philosophical guide and leader. Claimed to be 300 years old by the singer, Muhammad Suruj Dewan of Dhaka, when introducing the song and himself, the song says : «I have no need for wealth, O benign one, take me with you when leaving. Neither cremate my body nor throw it in the river when I die but repeat the name of my Master and bathe my body with the water in which he has washed his feet. Do not cut any bamboo from its grove to carry my body but use my Master’s walking stick. I have no need for a fresh cotton shroud but wrap my body in my Master’s worn out shirt... «. The song is accompanied by the instruments as described in the above text for title No.8. (Cf. Guru tumi ei golar-i har, CD-2, item 10. Moreover, the words and the spirit of this song echo a popular 15th century Hindu devotional song on Radha’s love for Krishna ) Recorded in Dhaka, August 1997. 7.50 mins.

CD 2

SONGS OF THE REFUGEES AND FREEDOM-FIGHTERS

(See Introduction p. 23 for description of instruments)

1. Nijer paye nije hete chal. «’Walk on your own feet, O Bengalis, brothers, Mujibar [the father of the nation] with arms in his hand is calling us. Bengalis are not afraid of the soldiers of the Khan [General Yayha Khan, the military Dictator of Pakistan at the time of the Bangladesh war in 1971]. Robbers coming from the west [Punjabis and Sindhis from West Pakistan] to this land of the Bengalis are turning our blood into lifeless water. In the name of Islam they are sucking us lett and right while fire rages in our stomach.... The Bengalis are firm about building their own nation refusing to live in misery...» Composed and sung impromptu on the spot by a Kabiyal (a type of poet-singer) named Muhammad Safi of Sandwip, Chittagong. Unaccompanied. Recorded in Calcutta, October 1971. 4.45 mins.

2. Koina, koina, bandhure. «O friend, do not speak of my misfortune as my lonely youth burns away smouldering each month of the year. When the water of the sea begins to boil in the month of Phalgun (February-March), my youthful desire agitates with hope. After Chaitra when the mangoes are ripe on the trees in the month of Baishakh (April-May), how can I eat them with my love being away? In the month of Jaistha (May-June), the lover-bee hums next to my room. In Ashadh (June-July), when the rains pour down and everyone goes out for showers, I stay in and cry. At the end of Shravan in the month of Bhadra (Aug.-Sept.) when the big palm fruits are ripe on the tree, how could I eat them in my misfortune! In the month of Ashwin (Sept. -Oct.) when the river is cool and the boatman sings of love, I hear him from my home and feel like asking him to fly to my love and bring me his news. How long can I watch out for his return and cry ?...» Called Baramasya, this is a seasonal song about parted lovers. It is sung unaccompanied by Muhammad Safi of Sandwip, Chittagong, as above. Recorded in Calcutta, October 1971. 4.10 mins.

3. Surja udala lal mari. «The Sun rose in a splash of red as my beloved left me, hurting me as if with a missile. There is no one to whom I could speak of my sorrows, of how my heart cries out through sleepless nights. As I speak of my beloved, my eyes flow away like the river Karnaphuli, with waves rising in my breast. Unaccompanied love song from Chittagong by Muhammad Safi of Sandwip, as above. Recorded in Calcutta. October 1971. 3.18 mins.

4. Chhoto chhoto dheu. «Descending from the Lusai Hills, the river Karnaphuli flows away raising gentle ripples in its water. On one bank the river is lined with green fields and on the other with villages and towns. As birds sing from the riverside trees, young women come to collect its water. Once upon a time when a young girl lost her ear-ring in its water, it was named Karnaphuli, the river of the earring. «The song of the Karnaphuli river. The text is set to a traditional melody and was written and sung by Malay Ghosh-dastidar of Chittagong. The song is accompanied by Dotara and Tabla. Recorded in a refugee camp in Kalyani, West Bengal, October 1971. 5.30 mins.

5. Malkha Banu. «Malkha Banu has seven brothers but unfortunate Monu Mla has none. How will Monu go to Malkha Banu’s home which is surrounded by marshes. The thunderous roars coming from the Dhol drums and the music of the Shahnai (the Bengali shawm, which has a high pitched sound) make Monu’s heart tremble with apprehension. Monu Mia comes from a land with big seas and Malkha will be married to him.» Traditional song from Chittagong. It is sung by Mangal Barua of Chittagong and is accompanied by Dotara and Tabla. Recorded in Calcutta, September, 1971. 3.35 mins.

6. Matir manush. «We have birthright to the soil of this land. We were born here to live and die. Our bodies are made of the same earth as that of our land and we shall fight to the end to detend it in order to lay within its deep embrace...» Patriotic song written and set to a traditional melody by Ramesh Shil and sung by Mangal Barua of Chittagong. It is accompanied by Dotara and Tabla. Recorded in Calcutta, September, 1971. 4.00 mins.

7. Janmabhumi janani. «O my motherland, my heart cries out for your sorrows as if you were my mother. You have fulfilled our life by giving over whatever you had of your own but now, where are you and where are we ? They have robbed and surrounded you, they have emptied you of all you had turning you into a beggar. They have never received love from their mother nor do they know how to value a mother.» A patriotic song by Chitta Bhuiya from Noakhali. It is accompanied by Dotara and Tabla. Recorded in Calcutta, September 1971. 2. 45 mins.

8. Tomar Bangla amar Bangla. «Glory be to Bengal that belongs to you and me. There is no difference between Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Buddhists in this Bengal where we were born. Mujibar who is leading us is the father of Bengal. Let us all salute him. ..» Sung by a group of refugee orphans from the children’s home Khelaghar at Kalyani. West Bengal. Recorded at Khelaghar, Kalyani, October, 1971. 1.50 mins.

9. Pal tule de. «Raise the sail, Robin, raise the sail of the boat in this gentle shivering breeze. The light of the day is disappearing into the evening sky...» A river song, it was sung by Gobinda Bagdi, aged 9, an orphaned child from East Pakistan. It was recorded in the above children’s home Khelaghar at Kalyani in October 1971. 1.50 mins.

10. Guru tumi amar ei golar-i har. «Master, you are the necklace of my neck, the gift of life, with unending qualities. My love for ornaments expresses my devotion to you, I wear ear-rings to hear your names and the nose-ring to inhale your perfume. Like the ring that adorns the finger, my heart is adorned by you. « Called Gurutatva in Hindu tradition, the song is expressive of devotion to the spiritual master, or guru as it is called in Bengali (cf. Murshidi, the Sufi devotional song on CD-1, item 10). Written and set to a traditional chanting melody by Balaram Sharma of Jessore, it was recorded in a Kalyani Refugee camp in October, 1971. 2.35 mins.

11. Mon tumi Darshanate gelena. «My heart, you failed to visit Darshana. You only kept waiting at Chuadanga without recognising Arangghata...» Written and set to a traditional chanting melody by Balaram Sharma of Jessore, as in above item No.10, this song consists of a list of names of villages and towns of both Bengals, East and West, through which the singer travelled to reach the refugee camp at Kalyani in West Bengal. The song also speaks of the places the singer would have liked to see but could not manage to stop. It was recorded in a Kalyani Refugee camp in October, 1971. 3.05 mins.

12. Mon pabaner naiya. «O the Sailor of my stormy heart, how are you going to row the boat of attachment which is full of desire, beauty and love ? Only those who are connoisseurs of the art of feelings can sail through the river of emotions. Taking your boat through the currents of desire, you will sink. « A Baul song (Cf. introduction pp. 4 & 5), it is written and sung by Baul Torap Ali Shah of Jessore with a Baul melody accompanying himself on the lute Sworaj. The song is also accompanied by a cluster of small jingling bells called the Ghunghur. Recorded in Calcutta in November, 1971. 3.35 mins.

13. Hai Sheikh Mujibar. Song in praise of Sheikh Mujibar Rahman, the father of the nation. Although the Sheikh at the time was held in a West Pakistani prison nearly 1500 miles away, his name was often associated with that of the Mukti Bahini, the liberation army during the war with Pakistan. The song beginning with the words: «Sheikh Mujibar has enchanted everyone. Robbing people of their hearts, he has come to liberate Bengal, leading the army of liberation», continues comparing the Sheikh with the legendary kings of Bengal through the ages. Sung by Baul Torap Ali Shah of Jessore as in above item 12, accompanying himself with the Sworaj. The rhythm was provided by a cluster of brass bells called the ghunghur and a pair of wooden clappers called the Kath-kartal. Recorded in Calcutta in November, 1971. 6.35 mins.

14. Ekbar phire chao-he praneshwar. «For once turn your eyes towards me, O Lord of my life. Your name is constantly on my tongue as I repeat it using my mouth as a rosary. How long will you keep me deceived, blinding me with hope ? My life is empty without you and I long to wash your feet with my tears.» A Baul song written and sung by Baul Torap Ali Shah of Jessore as in above item 12 and is accompanied by the Sworaj and the cluster of bells called the ghunghur. Recorded in Calcutta in November, 1971. 6.00 mins.

Recordings, photographs & text DEBEN BHATTACHARYA

© GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 1998.

Le domaine de prédilection de Deben Bhattacharya est la collection, le tournage et l’enregistrement de la musique folklorique, la chanson, la danse ainsi que la musique classique en Asie et en Europe.Depuis 1955, il a réalisé des films éducatifs, des documentaires, des disques, des brochures, des émissions radiophoniques et des concerts en direct relatifs à ses recherches. Il a également édité des traductions de la poésie médiévale de l’Inde.Entre 1967 et 1974, il a produit des films éducatifs, des disques, des brochures et des concerts pour des écoles et des universités en Suède, sponsorisé par l’institut d’état de la musique éducative: Rikskonsorter.Ses travaux ont également consisté en documentaires pour la télévision ainsi que des émissions sur le folklore, les traditions... pour : • British Broadcasting Corporation, Londres • Svorigos Radio, Stockholm • Norsk Rikskringkasting, Oslo • B.R.T. - 3, Bruxelles • Filmes ARGO (Decca), Londres • Seabourne Enterprise Ltd., R.U. • D’autres stations de radio en Asie et en Europe.Deben Bhattacharya a réalisé plus de 130 disques de musique folklorique et classique, enregistrés dans près de trente pays en Asie et en Europe. Ces disques sont sortis sous les étiquettes suivantes : •?Philips, Baarn, Hollande • ARGO (Decca), Londres • HMV & Columbia, Londres • Angel Records & Westminster Records, New York • OCORA, Disque BAM, Disque AZ, Contrepoint, Paris • Supraphone, Prague • HMV, Calcutta • Nippon Records, Tokyo.Deben Bhattacharya est également l’auteur de livres de traduction de la poésie médiévale indienne. Ces ouvrages ont été préparés pour la série de l’UNESCO, East-West Major Works, publiés simultanément en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis par G. Allen & Unwin, Londres, et par le Grove Press, New York, ainsi que Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi. Les titres comprennent : • Love Songs of Vidyapati • Love Songs of Chandidas • The Mirror of the Sky: songs of the bards of Bengal • Songs of Krishna.Deben Bhattacharya fait paraître en 1997, une collection de coffrets thématiques chez Frémeaux & Associés, regroupant ses meilleurs enregistrements de Musique du Monde et dotés de livrets qui constituent un appareil critique de documentation incomparable.

Deben Bhattacharya is a specialist in collecting, filming and recording traditional music, song and dance in Asia, Europe and North Africa.Since 1955 he has been producing documentary films, records, illustrated books and radio programmes related to many aspects of his subject of research. His films for TV and programmes for radio on traditional music and rural life and customs have been broadcast by: • the BBC, Thames Television, Channel Four, London • WDR-Music TV, Cologne • Sveriges Radio/TV, Stockholm • BRT-3, Brussels • Doordarshan-TV, Calcutta • English TV, Singapore • and various other radio and television stations in Asia and Europe.Deben Bhattacharya has produced more than 130 albums of traditional music recorded in about thirty countries of Asia and Europe. These albums have been released by: • Philips, Baarn, Holland • ARGO (Decca Group), London • HMV & Clumbia, London • Angel Records & Westminster, New York • OCCORA, Disque BAM, Contrepoint, Paris • Supraphone, Prague • HMV, Calcutta • Nippon-Westminster & King Records, Tokyo.In addition, Deben Bhattacharya is the author of books of translations of Indian medieval poetry and songs. These publications have been prepared for the UNESCO’s East-West Major Works series published simultaneously in England and the USA by G. Allen & Unwin, London, and by the Grove Press, New York, and by Hind Pocket Books, New Delhi. The titles include: • Love Songs of Vidyapati • Love Songs of Chandidas • The Mirror of the Sky/Songs of the Bards of Bengal • Songs of Krishna.Deben Bhattacharya released a new collection of thematic double Cd Set, published by Frémeaux & Associés, with booklet comprising essential documentary and musicological information.

CD 1

01. Bhatial ganger naiya. 4’56

02. Ujan ganger naiya. 5’58

03. Maynamatir gan. 4’06

04. Ulta desh. 4’06

05. Ashole binash hoila. 4’46

06. Sharanarthir gan. 4’49

07. Dotara. 7’10

08. Ami tomay bhalobeshe. 5’39

09. Manush banaichhe Allah.? 4’27

10. Murshidi. 8’03

CD 2

01. Nijer paye nije hete chal. 4’47

02. Koiona, koiona, bandhure. 4’14

03. Surja udala lai mari. 3’18

04. Choto choto dheu. 5’37

05. Malkha Banu. 3’45

06. Matir manush. 4’04

07. Janmabhumi janani. 2’49

08. Tomar Bangla amar Bangla. 1’59

09. Pal tule de. 2’00

10. Guru tumi amar ei golar-i har. 2’42

11. Mon tumi Darshanate gelena. 3’17

12. Mon pabaner naiya. 3’50

13. Hai Sheikh Mujibar. 6’58

14. Ekbar phire chao-he praneshwar. 6’08

CD Echoes from Bangladesh © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)