- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

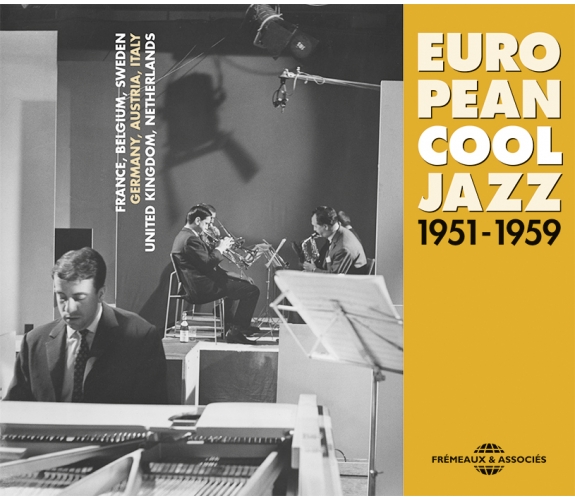

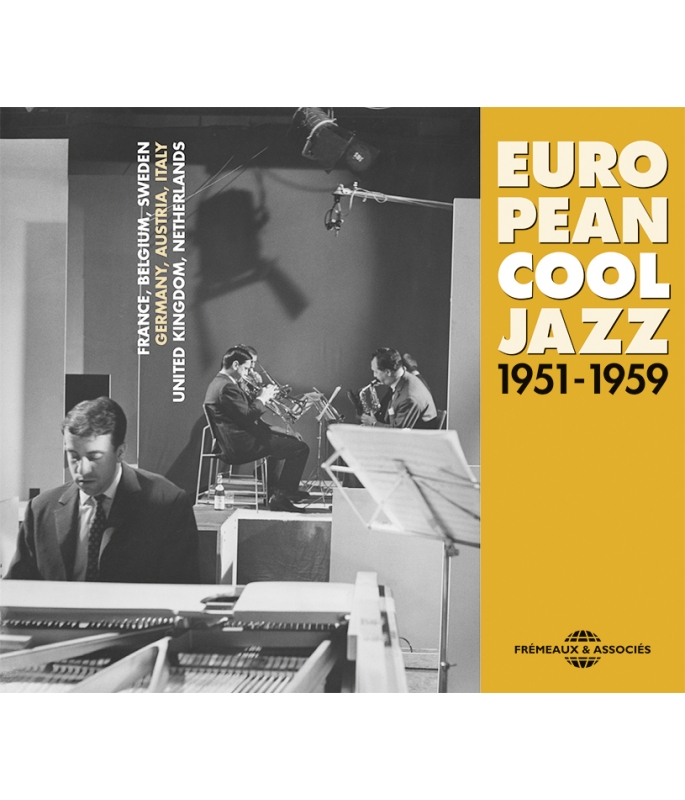

FRANCE, BELGIUM, SWEDEN, GERMANY, AUSTRIA, ITALY, UNITED KINGDOM, NETHERLANDS

Ref.: FA5428

EAN : 3561302542829

Direction Artistique : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 31 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

FRANCE, BELGIUM, SWEDEN, GERMANY, AUSTRIA, ITALY, UNITED KINGDOM, NETHERLANDS

Loin de se cantonner, comme cela a trop longtemps été leur lot, dans une imitation stérile des formes américaines du jazz, les jeunes compositeurs français, dont Hodeir est l’un des plus prometteurs, vont hardiment de l’avant.

Boris VIAN (1954)

Far from confining themselves to sterile imitations of American jazz forms (as has been their fate for much too long), the young French composers — with Hodeir one of the most promising — are striding boldly forwards.

Boris VIAN (1954)

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : Alain TERCINET

DROITS : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

CD 1 - HENRI RENAUD ALL STARS : PARIS, JE T’AIME, 1953 • BOBBY JASPAR with THE HENRI RENAUD QUINTET : TOUT BLEU, TOUT BLEU, 1952 • BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : SANGUINE, 1954 • BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : JEUX DE QUARTES, 1954 • BOBBY JASPAR JOUE HENRI RENAUD : MARCEL THE FURRIER, 1954 • JAZZ GROUPE DE PARIS : ON A BLUES, 1954 • BOBBY JASPAR PLAYS : TEANGA, 1955 • DAVID AMRAM/BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET : OCCASION, 1955 • DON RENDELL & BOBBY JASPAR : KING FISH, 1955 • BERNARD PEIFFER AND HIS ST GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS ORCHESTRA : DON’T TOUCH THE GRISBI, 1954 • FATS SADI AND HIS COMBO : BIG BALCONY, 1954 • FOH-RENBACH FRENCH SOUND : LE CHALAND QUI PASSE, 1954 • ARMAND MIGIANI NONET : BLACK BOTTOM, 1956 • KENNY CLARKE & HIS ORCHESTRA : JACKIE MY LITTLE CAT, 1957 • JAY CAMERON’S INTERNATIONAL SAX BAND : BLUE NOTE, 1955 • HENRI RENAUD SEXTET : INFLUENCE, 1955 • CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ORCHESTRA : LES ROIS MAGES, 1957 • JAZZ ON THE LEFT BANK : JAGUAR, 1956 • SACHA DISTEL : ON SERAIT DES CHATS, 1956 • BERNARD ZACHARIAS & SES SOLISTES : WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE ?, 1956 • RÉUNION À PARIS : ILLUSION, 1956 • JACK DIEVAL’S ALL STARS : BLUE SMOKE, 1956 • WILLIAM BOUCAYA & HIS NEW SOUND SEXTET : RÊVE, 1956 • RAYMOND LE SÉNÉCHAL SEXTET : VENEZ DONC CHEZ MOI, 1953.

CD 2 - LARS GULLIN & HIS BAND : MERLIN, 1952 • CARL-HENRIK NORIN ORKESTER : SHORTLY, 1955 • LARS GULLIN OCTET : FEDJA, 1956 • BENGT HALLBERG ENSEMBLE : MEATBALLS, 1954 • LARS GULLIN SEXTET : LATE SUMMER, 1955 • HANS KOLLER’S NEW JAZZ STARS with Lars Gullin & Lee Konitz : PASSAGLIA, VARIATIONS n° 8, 1956 • HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : UNTER DEN LINDEN, 1953 • HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : IRIS, 1955 • JUTTA HIPP QUINTET : MON PETIT, 1954 • ALBERT MANGELSDORFF UND SEINE FRANKFURT ALL STARS : ADLON 1925, 1958 • THE AUSTRIAN ALL STARS : MEKKA, 1954 • GIL CUPPINI E IL SUO COMPLESSO : AULD LANG SYNE, 1954 • ERALDO VOLONTÈ E IL SUO QUINTETTO : KONITZ IN ITALY, 1959 • MODERN JAZZ GANG : ARPO, 1959 • BASSO-VALAMBRINI OCTET : BLUES FOR GASSMAN, 1959 • BASSO-VALAMBRINI OCTET : BUT NOT FOR ME, 1959 • THE WESSEL ILCKEN COMBO : A DANDY LINE, 1955 • JOHNNY DANKWORTH SEVEN : LEON BISMARK, 1951 • VIC LEWIS NEW MUSIC : JD TO VL, 1952 • RONNIE SCOTT JAZZ GROUP : S’IL VOUS PLAÎT, 1955

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Paris, je t'aimeHenri Renaud All Stars00:04:121953

-

2Tout bleu, tout bleuBobby Jaspar with The Henri Renaud QuintetR. Gilbert00:03:451953

-

3SanguineBobby Jaspar's New Jazz00:02:381954

-

4Jeux de quartesBobby Jaspar's New Jazz00:02:351954

-

5Marcel The FurrierBobby Jaspar00:02:151954

-

6On A BluesJean Liesse, Pierre Michelot, André Hodeir00:04:041954

-

7TaengaBobby Jaspar00:03:541955

-

8OccasionBobby Jaspar Quintet & David Amram00:02:511955

-

9King FishDon Rendell & Bobby Jaspar00:03:271955

-

10Don't Touch The GrisbyBernard Peiffer And His Saint-Germain-des-Prés Orchestra00:02:061954

-

11Big BalconyFats Sadi And His Combo00:03:351954

-

12Le chaland qui passeFohrenbach French Sound00:02:471954

-

13Black BottomArmand Mignani Monet00:03:151956

-

14Jackie My Little CatKenny Clarke & His Orchestra00:03:281957

-

15Blue NoteJay Cameron's International Sax Band00:03:111955

-

16InfluenceHenri Renaud SextetHenry Renaud00:03:381955

-

17Les Rois MagesChristian Chevallier Orchestra00:03:311957

-

18JaguarJazz On The Left Bnak00:02:481956

-

19On serait des chatsSacha Distel00:03:051956

-

20What Is This Thing Called LoveBernard Zacharias & ses Solistes00:02:341956

-

21IllusionMartial Solal, Kenny Clarke00:03:181956

-

22Blue SmokeJack Dieval's All Stars00:02:491954

-

23RêveWilliam Boucaya & His New Sound Sextet00:02:511954

-

24Venez donc chez moiRaymond Le Sénéchal Sextet00:03:071953

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1MerlinLars Gullin & His Band00:03:341952

-

2ShortlyCarl-Henrik Norin Orkester00:02:581955

-

3FedjaLars Gullin Octet00:05:051955

-

4MeatballsBengt Hallberg Ensemble00:03:241954

-

5Late SummerLars Gullin Sextet00:05:241955

-

6Passaglia Variations n°8Hans Koller's New Jazz Stars with Lars Gullin & Lee Konitz00:03:041956

-

7Unter Den LindenHans Koller's New Jazz Stars00:02:581953

-

8IrisHans Koller's New Jazz Stars00:04:121955

-

9Mon petitJutta Hipp Quintet00:03:161955

-

10Adlon 1925Albert Mangelsdorff und Seine Frankfurt All Stars00:02:291958

-

11MekkaThe Austrian All Stars00:02:161954

-

12Auld Lang SyneGil Cuppini e Il Suo Quintetto00:02:591954

-

13Konitz In ItalyEraldo Volonté E Il Suo Quintetto00:03:111959

-

14ArpoModern Jazz Gang00:04:551959

-

15Blues For GassmanBasso-Valambrini Octet00:02:511959

-

16But Not For MeBasso-Valambrini Octet00:03:211960

-

17A Dandy LineThe Wessel Ilcken Combo00:02:501955

-

18Leon BismarkJohnny Dankworth Seven00:03:301951

-

19JD To VLVic Lewis New Music00:03:351953

-

20S'il vous plaïtRonnie Scott Jazz Group00:02:331955

-

21Thames WalkRon Rendell Sextet00:02:551955

-

22Tam O'ShanterJohnny Keating and His All-Stars00:04:361957

European cool jazz FA5428

EUROPEAN COOL JAZZ1951-1959

EUROPEAN COOL JAZZ

Jeudi 14 juin 1951. À l’occasion de la « soirée jazz » du 3ème Festival de Musique de Clamart, les représentants du « vieux style » avaient été invités en nombre, André Reweliotty, Eddie Bernard, Claude Bolling, à la tête de leurs formations respectives. Annoncé mais absent en raison d’un accident d’auto, Sidney Bechet fut remplacé au pied levé par Don Byas. Également programmé, le sextette d’Henri Renaud composé de deux Américains fraîchement débarqués - un saxophoniste ténor, Sandy Mosse, un guitariste, Jimmy Gourley -, d’un Belge Bobby Jaspar, ténor lui aussi, et de trois Français, Pierre Michelot, Pierre Lemarchand et Henri Renaud : « À Paris alors, nous étions les seuls à jouer une musique où se mêlaient l’influence de Charlie Christian et de Lester Young et celle de Dizzy Gillespie et Charlie Parker. En France, la rupture de toute relation avec l’Amérique, due à la seconde guerre mondiale, a fait qu’à la Libération, nous sommes passés brutalement de Django Reinhardt à Parker, ignorant le rôle primordial joué par Charlie Christian et Lester Young (1). » Le Prez dont André Hodeir disait : « On a cru longtemps que Lester Young avait renouvelé le style du ténor ; c’est une nouvelle conception du jazz qu’il a fait naître (2). » Une vérité dont Jimmy Gourley se faisait l’ardent propagantiste. « C’est grâce à lui que j’ai connu le jazz que j’aime. Sans lui j’aurais certainement ignoré Al Cohn, Tiny Kahn, Johnny Mandel et, cachés derrière eux, Lester et le Count (3) » dira Henri Renaud, alors fasciné par Al Haig. En compagnie de Sandy Mosse, un inconditionnel de Lester et d’Al Cohn, de Bobby Jaspar, admirateur de Stan Getz et de Warne Marsh, et de Jimmy Gourley, disciple de Jimmy Raney l’inventeur d’une approche nouvelle de la guitare héritière de Charlie Christian, il allait faire découvrir aux Parisiens une forme de jazz moderne. Inédite ici, elle entrait dans la mouvance de ce qui se développait marginalement à New York et ouvertement sur la côte Ouest.

Ayant obtenu à Clamart un beau succès, le sextette se vit offrir l’opportunité d’enregistrer une dizaine de faces 78 tours. L’occasion pour lui d’afficher ses prises de position à une période où « la guerre du jazz était une réalité. Il fallait choisir son camp » rappellera Henri Renaud. Mis en présence de thèmes comme Godchild, Lady Be Bad et So What Could Be New ?, le chroniqueur (anonyme) de Jazz Hot botta en touche : l’orchestre jouait « cool » , ses interprètes étaient blancs donc le « cool » était au bop ce que le Dixieland était à la musique de la Nouvelle-Orléans. C. Q. F. D.

« Je déteste le mot « cool ». Que peut-il vraiment dire puisque l’on range communément sous cette étiquette des esthétiques aussi différentes que celle de Lennie Tristano, celle des « Brothers », celle qui présida à la West Coast ? (4) » écrira plus tard Henri Renaud qui aurait pu ajouter à sa liste le nonette de Miles Davis, responsable du tournant négocié par Bobby Jaspar : «C’est lorsque j’entendis Boplicity que je quittais le laboratoire de chimie où je travaillais pour me consacrer à cette musique que je jugeais enfin digne d’un avenir esthétique exceptionnel (5).»

Il n’empêche. Le terme « cool » demeurera, englobant ce jazz qui, durant une décennie, phagocyta à doses variables les apports des esthétiques précitées, les malaxant pour inventer, à chaque fois, une musique nouvelle.

« …Henri a fait œuvre de novateur pour le jazz moderne en France […] Ce style et ce répertoire, qui ont été maintenant adoptés un peu partout, ne se pouvait alors entendre qu’au Tabou, où Henri résidait avec son orchestre. » Un extrait du compte-rendu signé Gérard Pochonet, paru dans Jazz Hot, à propos de « New Sounds from Belgium ». Le premier album enregistré nominativement par Bobby Jaspar qui respectait alors en tout point les caractères liés à la mouvance dans laquelle il entendait évoluer : « Les qualités primordiales de ces musiciens sont la sobriété et une sorte de dignité musicale, laquelle, nous le croyons, leur a valu le surnom de « cool ». Pas de cris pour rien, pas de dithyrambes romantiques « la main sur le cœur » mais juste ce qu’il faut pour que ce soit swing et musical au maximum (6). »

Sous le titre Tout Bleu, Tout Bleu, Jaspar interprétait Die Gantze Welt Ist Himmelblau tiré de l’opérette « L’auberge du Cheval Blanc ». Un choix incongru de prime abord qui, en fait, marquait la distance qu’il entendait maintenir entre lui et ses inspirateurs. Dave Amram : « Pratiquement chaque saxophoniste ténor était alors influencé par Prez. Mais, au point de vue mélodique, Bobby sut se dégager de cette allégeance. Ses points de référence étaient clairement européens, français ou belges (7). »

Ce ne fut pas alors le seul exemple de recours à une thématique insolite. Ainsi Henri Renaud, à la tête de onze musiciens, servit une version à tout le moins inattendue de Paris je t’aime, l’un des grands succès de Maurice Chevalier. Il en avait conçu l’arrangement avec l’assistance de Francy Boland, pianiste et compositeur, également orchestrateur de Don’t Touch the Grisbi, un thème que son auteur, Bernard Peiffer, interpréta en compagnie de son « St Germain-des-Prés Orchestra ».

Boland était né à Namur et Bobby Jaspar, le porte-étendard, catalyseur et vulgarisateur du « jazz frais » hexagonal, à Liège. Qu’en serait-il advenu sans l’intervention de renforts venus de Belgique ? René Thomas, Benoît Quersin, Christian Kellens, tous trois mis en valeur par Henri Renaud dans Influence, l’irremplaçable Sadi qui, à la tête de son ensemble de la « Rose Rouge », interprétait Big Balcony. Une composition et un arrangement de Jaspar à la gloire d’un hôtel de la rue Dauphine, « Le Grand Balcon », où de nombreux jazzmen avaient élu domicile.

À Paris, Jaspar disposait de partenaires acceptant avec la meilleure grâce du monde de se plier à la discipline que sa musique exigeait. Maurice Vander au piano, le trompettiste Roger Guérin, interlocuteur idéal dans toutes les expériences aussi audacieuses fussent-elles, Jean-Louis Chautemps, William Boucaya, Armand Migiani, Jean-Louis Viale le batteur favori d’Henri Renaud, et Pierre Michelot. Immense bassiste et arrangeur méconnu, son Jackie, My Little Cat avait remporté, devant des concurrents venus de l’Europe entière, le Prix du Cinquantenaire du Jazz décerné par le Hot Club de Paris.

Contribuaient aussi à enrichir par leur talent et leur science nombre de séances, des américains de passage comme Buzz Gardner, Nat Peck, tromboniste et arrangeur, le corniste David Amram qu’un autre exilé temporaire, le saxophoniste baryton Jay Cameron, présenta à Bobby Jaspar qui s’empressa de le choisir comme interlocuteur. Occasion, signé de ce nouveau partenaire, pérénise une entente qui n’avait rien de superficielle.

Pour sa part, aux côtés de Barney Wilen et de Jean-Louis Chautemps, Jay Cameron avait intégré Jaspar à son « International Sax Band » qui entendait rendre hom-mage à sa manière aux « Brothers ». Ce qui lui valut de se faire étriller par Daniel Filipacchi (et non par Raymond Fol comme le laissait supposer la signature) de telle manière qu’il adressa à Jazz Magazine une lettre ouverte co-signée par vingt musiciens. Blue Note montre que la vérité était de leur côté.

Pianiste dans l’orchestre de la « Rose Rouge » et passionné d’écriture, Christian Chevallier allait bientôt se révéler comme un arrangeur exceptionnel. Après avoir prêté main forte à Henri Renaud pour Marcel the Furrier, il assura seul le traitement de toutes les compositions - King Fish de Bill Holman en est une - sur lesquelles le tandem Jaspar/Amram affrontait Don Rendell, alors le meilleur ténor cool anglais. Titulaire du prestigieux prix Stan Kenton, l’occasion fut offerte à Christian Chevallier d’enregistrer sous son nom. Chose rare, André Hodeir signa les notes de pochette de l’un de ses albums, « 6+6 » : « Écoutons par exemple Les Rois Mages où le thème, d’abord exposé par le cor, se « jazzifie » peu à peu, comme gagné par la contagion des « backgrounds » (ou motifs d’accompagnements) qui finit par le contraindre en quelque sorte à s’exprimer sous une forme purement jazzistique qu’il n’avait pas au début de l’œuvre. » Hodeir ajoutait : « Quoi qu’on en ait écrit, l’expérience des arrangeurs du groupe Davis conditionne encore, pour un temps, l’esthétique de l’orchestre de chambre, dans le jazz. »

Qui aurait pu les dépasser pour tenter d’aller plus loin ? Bobby Jaspar avait sa petite idée : « Je crois pouvoir affirmer que si une nouvelle évolution comparable à celle amorcée par la session Capitol a lieu en France, c’est à André Hodeir que nous le devrons (8). » Le « Bobby Jaspar’s New Jazz » avait gravé Sanguine, un beau thème d’Henri Crolla utilisé par Hodeir comme prétexte à entrelacs de lignes mélodiques et Jeux de quartes. Un arrangement de Jaspar lui-même tentant une incursion dans le domaine dodécaphonique, ce qui témoignait de son vif intérêt pour les recherches menées par le « Jazz Groupe de Paris » dont il avait été le co-fondateur avec André Hodeir. Extrait d’ « Essais », album qui marqua l’acte de naissance de l’ensemble, On a Blues traitait des rapports qui pouvaient s’établir entre un simple riff orchestral évoluant progressivement et une improvisation sur le blues interprétée par Bobby Jaspar.

Dernier avatar lié à ces incursions dans des territoires jusqu’alors peu fréquentés par le jazz, Teanga. Une composition originale où Jaspar se fait accompagner par une clarinette, une flûte, un cor, un hautbois, un basson, une basse et une batterie. Une instrumentation alors inusitée, tellement expérimentale que l’album « Gone with the Winds » resta dix-huit mois sous le boisseau. Jusqu’à l’automne 1956, date à laquelle Bobby Jaspar était établi aux Etats-Unis, après avoir joué à Paris avec Chet Baker dont la venue avait conforté la légitimité du jazz cool.

Si, à l’exemple de Chet, Buzz Gardner, David Amram et Jay Cameron avaient regagné leur pays d’origine, d’autres « touristes » vinrent les remplacer. Allen Eager, figure historique du ténor moderne qui, dans les studios parisiens, croisa le fer avec Jimmy Deuchar, trom-pettiste venu d’Angleterre ; Billy Byers, tromboniste, compositeur et arrangeur, arrivé à Paris au début de 1956 à la demande de Ray Ventura reconverti en éditeur musical. Il y restera pratiquement deux ans, éminence grise de maintes séances dont l’une fut dirigée par Sacha Distel, excellent guitariste, invité régulier de l’orchestre du Tabou, avant de devenir le partenaire en titre de Bobby Jaspar au Club Saint Germain. Dans On serait des chats, il évolue au sein d’un sextette sans piano dont la sonorité était définie par le timbre très particulier de la trompette de Jean Liesse joint à celui du baryton (ou de la clarinette-basse) de William Boucaya. Trois ans plus tôt, Sacha avait été partie prenante dans une séance dirigée par celui qui deviendra son pianiste régulier, Raymond Le Sénéchal. Extrait de cet album tombé dans les oubliettes, Venez donc chez moi donnait à entendre un délicat et talen-tueux clarinettiste, Francis Weiss (9).

En tant qu’instrumentiste, en compagnie de son compatriote le trompettiste Dickie Mills, Billy Byers interprétera Jaguar, une composition et un arrangement signé d’un nouveau venu sur la scène du jazz parisien, le pianiste Martial Solal. Son originalité foncière rendrait fallacieuse toute tentative d’annexion à une quelconque école.

Dans l’histoire du jazz cool hexagonal, le cas de Jean-Claude Fohrenbach est unique. Partenaire et complice de Boris Vian au Club Saint Germain, considéré comme un excellent disciple de Coleman Hawkins, à un moment donné il constata que sa pratique du ténor se trouvait en complet décalage avec ses nouvelles compositions marquées par sa passion pour Debussy, Ravel et Bartok : « Je me trouvais donc devant un curieux paradoxe : il n’y avait pas de place pour moi dans MA musique. J’ai donc cherché une voie « saxophonistique » corres-pondant à la musique que j’entendais, que j’écrivais ; il fallait que j’entende si quelqu’un jouait déjà comme ça. Et ce fut très dur. Heureusement cette musique n’est pas restée marginale. Dès 1952, on découvrit en France les musiciens West Coast comme Stan Getz, Warne Marsh, Jimmy Giuffre etc… Et je me suis dit : Tiens ! Enfin des gars qui jouent comme moi. C’était tout le contraire d’avant où je cherchais à jouer comme Hawkins. Il est certain que, n’étant pas sourd, j’avais sûrement déjà été influencé par la West Coast, même à petite dose, mais je n’avais pas cherché à jouer comme eux, ça s’est fait tout seul (10). » L’idée d’interprèter le Chaland qui passe – d’origine transalpine mais naturalisé avec grand succès en France - répondait à l’une des soucis de « Fofo », à savoir bâtir un répertoire à base de « stan-dards » hexagonaux.

Blue Smoke de Jack Dieval, Rêve joué par William Boucaya, Black Bottom servi par le nonette d’Armand Migiani, montrent l’emprise exercée par l’esthétique « cool » sur toute une partie du jazz français de l’épo-que ; tout comme les deux albums « Gershwin Parade » et « Cole Porter Parade » signés de Bernard Zacharias. Avant de s’associer à Henri Viard pour expédier dans la « Série Noire » Hamlet devenu « L’embrumé », cet ancien tromboniste de l’orchestre Claude Luter faisait - sans scrupules excessifs mais avec beaucoup de talent - des infidélités au « N. O. Revival ». Tout comme André Persiany qui, oubliant un instant son obédiance au jazz « classique », écrivit un arrangement fleurant bon la West Coast sur What Is This Thing Called Love ? L’occasion d’entendre le trompettiste trop oublié Bernard Hulin, et, dissimulé derrière le pseudonyme de Low Reed, Michel de Villers.

Le 13 mai 1955, à l’occasion d’un concert donné à l’Apollo, le All-Stars d’Henri Renaud accueillit Lars Gullin, saxophoniste baryton, compositeur, arrangeur, né en Suède. Un pays où la révolution par la douceur s’était imposée rapidement – dès 1955, Shortly ren-dait hommage à Shorty Rogers –, certaines de ses composantes trouvant un écho dans les traditions musicales suédoises. Ack Värmeland du Sköna, thème folklorique gravé in situ par Getz en 1951, entra ainsi sans peine dans la thématique cool sous le titre de Dear Old Stockholm. Quand à la musique de Lars Gullin elle-même, empreinte de ce lyrisme doux-amer qui imprègne plusieurs formes d’expressions musicales suédoises – Late Summer n’est pas sans évoquer certaines œuvres de compositeurs scandinaves du XIXème – , elle fut même qualifiée de « Fäbodjazz », terme faisant allusion à une fusion entre folklore et jazz.

Enfant prodige qui, à treize ans jouait de la clarinette dans un orchestre militaire, Lars Gullin avait débuté professionnellement en 1947 : « J’ai commencé à utiliser un baryton au mois de septembre 1949 et six mois après seulement, j’étais dans un studio aux côtés de Zoot Sims. Je débutais et la nervosité m’asséchait tellement la bouche que ma sonorité en était rauque. Je m’en suis sorti à ma façon et on m’a dit que c’était OK (11). » Ce fut bien l’avis de Zoot, premier musicien américain à saluer en lui un frère. Suivront Stan Getz et Lee Konitz : « Il avait l’une des plus belles sonorités qui soient, influencée par celle de Mulligan au sein du Nonet de Miles Davis ; ce genre de sonorité de baryton qui rejoint presque celle d’un ténor (12). » En 1955, Lars Gullin partagea l’affiche de certains concerts avec Chet Baker qui, plusieurs années après, lui rendit ce tribut : « Il m’a beaucoup impressionné. Il possédait une manière très mélodique, fluide, oui fluide, de naviguer au travers des changements d’accords. D’une certaine façon Lars jouait avec beaucoup plus de flamme et d’autorité que Gerry (13). »

Lars Gullin n’était pas le seul alors à incarner l’âge d’or d’un jazz suédois qui comptait nombre de remarquables musiciens. Présents sur Merlin et Fedja, le tromboniste Åke Persson et Arne Domnerus, un disciple de Benny Carter qui avait intelligemment assimilé l’esthétique cool sans se dédire pour autant ; Rolf Billberg dans Late Summer ; le clarinettiste Putte Wickman sur Meatballs, composé et arrangé par Bengt Hallberg qui revendiquait le patronage de Tristano à l’égal de ceux de Teddy Wilson et Bud Powell.

Immense musicien dont l’univers personnel se trouva en symbiose avec un courant que, de ce fait, il glorifia comme peu d’autres le firent, Lars Gullin effectua de nombreux déplacements en Europe durant la décennie 1950-1960. En Allemagne entre autres, où, au milieu des années 1950, les diatribes à l’encontre du jazz - héritières du national-socialisme - ne manquaient pas. Sans pour autant dissuader les musiciens de s’y adonner. Le style swing avait ses supporters, d’autres se tournaient vers le New Orleans Revival et, après une courte période d’adaptation, le jazz nouveau eut ses adeptes. Peu nombreux dans un premier temps.

Marqué par Warne Marsh, Lee Konitz et Zoot Sims, Hans Koller, d’origine autrichienne, s’imposera vite comme l’un des plus intéressants saxophonistes ténor euro-péens. L’un des plus audacieux aussi lors de ses dialogues avec le pianiste Roland Kovac, également compositeur, pour qui « l’auditeur européen, avec mille ans de tradition polyphonique, est suffisamment éduqué pour comprendre des formes polyphoniques complexes (14). » Témoins, Iris et Passaglia, Variations n°8 sur lequel Lee Konitz et Lars Gullin rejoignent Hans Koller dans une improvisation collective sur base de passacaille.

Le premier quintette constitué par Hans Koller - il interprète ici Unter Den Linden - comprenait un musicien d’exception, Albert Mangelsdorff appelé à devenir une figure incontournable du trombone moderne. « C’est une des peu nombreuses personnalités originales du monde du jazz. Son style – en dehors d’une incroyable adresse technique – est caractérisé par une liberté mélodique exceptionnelle (15). » Adlon 1925 confirme la pertinence de ce jugement porté par Leonard Feather.

Autre partenaire choisi par Hans Koller, la pianiste Jutta Hipp. Née à Leipzig, elle avait quitté l’Allemagne de l’Est pour continuer à interpréter sa musique. Très influencée par Lennie Tristano avec lequel elle entretint une correspondance, Jutta Hipp monta par la suite sa propre formation. Un ensemble proche des quintettes tristaniens, autant par l’esprit que par le choix ins-trumental de deux saxophonistes comme section mélodique ; un alto, Emil Mangelsdorff, un ténor, Joki Freund. Sa spécificité tenait à un répertoire composé de thèmes originaux comme Mon Petit, extrapolé de I Never Knew, que la formation interprète ici en public avec une belle cohésion (16). Une qualité que pouvait légitimement revendiquer l’« Austrian All Stars », créé en 1954 par cinq musiciens issus de divers orchestres de danse. Le piano y était tenu par Joe Zawinul, également compositeur et arrangeur, dont les partitions, Mekka par exemple, ressemblaient étrangement à ce qui se jouait alors en Californie. Bien loin de Cannonball Adderley et de Weather Report.

Invité en 1959 au Festival de Jazz de San Remo, Lars Gullin séjourna en Italie où, depuis la fin de la guerre, le jazz s’ouvrait à tous les styles. L’arrangement – inattendu - concocté par l’excellent batteur Gil Cuppini sur Auld Lang Syne montre que le jazz moderne n’était pas resté lettre morte de l’autre côté des Alpes où les musiciens de valeur ne manquaient pas. Lars Gullin laissa de nombreuses traces de son passage en leur compagnie - il retrouva même Chet Baker (17).

Gullin enregistra le remarquable Blues for Gassman au sein d’un octette dirigé par le tandem Basso-Valdambrini ; une association-phare du jazz italien dont l’existence s’étendit sur près de quarante années, le plus souvent au sein d’un quintette. Lorsque Gianni Basso, saxophoniste ténor de grande classe alors influencé par Stan Getz, et le trompettiste Oscar Valdambrini invitèrent le tromboniste à pistons Dino Piana, leur ensemble se rapprocha quelque peu du sextette de Gerry Mulligan auquel il avait bien peu à envier, témoin But Not For Me.

Un an avant Lars Gullin, accompagné de Renato Sellani, Franco Cerri et Gil Cuppini, Lee Konitz avait mis en boîte Line in Sea. Qui y resta. Eraldo Volontè lui offrit une revanche en enregistrant à Milan Konitz in Italia, co-signé par le dédicataire. Parallèlement, à Rome, le Modern Jazz Gang réunissait, sous la houlette de Sandro Brugnolini, d’anciens membres du Junior Dixieland Gang créé pour perpétuer la musique de Bix Beider-becke. Une démarche qui les entraina logiquement en direction du jazz cool dont ils donnèrent une vision très personnelle, exposée au travers d’un certain nombre de pièces telles Arpo dédié au critique Arrigo Polillo et Miles Before and After. Une remarquable suite dont la durée ne permet pas de trouver place ici.

Chacun le sait, les Britanniques ne font rien comme les autres. Si les musiciens étrangers étaient partout accueillis à bras ouverts, il en était bien autrement au Royaume-Uni. Un décret de la « National Federation of Jazz Organization of Great Britain and Northern Ireland » leur interdisait tout bonnement de s’y pro-duire, toute transgression valant à ses responsables d’être traduits devant les tribunaux. Ce qui arriva aux coupables d’une venue plus ou moins en catimini de Coleman Hawkins puis de Sidney Bechet. Une décision qui favorisait les autochtones mais les maintenaient tout autant dans un splendide isolement. Les récalcitrants à un tel état de chose découvrirent une échappatoire. Puisque le jazz ne pouvait venir à eux, ils iraient à lui : il suffisait de signer un engagement dans l’un des orchestres liés aux paquebots reliant la Grande-Bretagne aux USA.

Employé à bord du « Queen Mary », le saxophoniste alto, également compositeur et arrangeur, Johnny Dankworth put ainsi entendre Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie au Birdland et faire connaissance du nonette de Miles Davis. En écho, dès 1951, il grava Leon Bismark, hommage à Bix Beiderbecke considéré comme l’un des pères spirituels du jazz cool. S’y faisaient entendre Jimmy Deuchar, alors très marqué par Miles Davis, et Don Rendell, à l’époque disciple de Pres, qui croisera le fer avec Bobby Jaspar à Paris, l’année même où il enregistrait Thames Walk en compagnie de Ronnie Ross. Le saxophoniste baryton probablement le plus entendu au monde mais de manière anonyme. C’est lui qui interprète l’introduction et un solo dans le tube de Lou Reed, Walk on the Wild Side. Un honneur dû au fait que le producteur de l’album, David Bowie, s’était souvenu que, lorsqu’il s’appelait encore David Jones, il avait pris à douze ans des leçons de saxophone avec… Ronnie Ross.

En raison de la solide amitié qui le liait à Stan Kenton, Vic Lewis servait d’intermédiaire entre la West Coast et l’Angleterre. À la tête de son grand orchestre créé en 1946, il programmait régulièrement les partitions signées Pete Rugolo, Bill Holman, Shorty Rogers, Bill Russo ou Gerry Mulligan, que lui envoyait Kenton ; il réussira même à enregistrer avant lui Blues in Riff sous le titre de Hammersmith Riff. Ne se satisfaisant pas de cette manne, Vic Lewis fit orchestrer pour son usage personnel, quel-ques thèmes de Mulligan - Nights at the Turntable, Westwood Walk, Sextet, Bark for Barksdale – par Johnny Keating. L’arrangeur s’en souviendra lors-que, trois ans plus tard, il réunira la fine fleur des jazz-men… écossais dans l’album « Swin-ging Scots » dont est extrait Tam O’Shanter com-posé par Jimmy Deuchar.

Vic Lewis privilégiait les formations étoffées, toutefois, au mois de mars 1953, il dirigea en studio un nonette expérimental qui grava quatre pièces fort intéressantes dont JD to VL de Johnny Dankworth. Parmi les interprètes, au ténor Kathleen Stobart, certainement l’une des toutes premières jazzwomen européennes, historiquement parlant. Céda aussi fugitivement aux sirènes «cool», le musicien d’outre-Manche le plus célèbre ici en raison du club londonien portant son nom, Ronnie Scott. Tout de go, il emprunta au nonette de Miles Davis, le S’il vous plaît de John Lewis.

En Angleterre, Suède, Allemagne, Italie, tout comme en France et en Belgique, la vague « cool » toucha un temps le jazz européen. Elle effleura aussi bien d’autres pays, ce que suggère A Dandy Line - une composition de Jack Montrose gravée par Chet Baker - reprise à Hilversum sous la houlette du batteur Wessel Ilcken, rencontré à Paris aux côtés Billy Byers et Martial Solal.

Là-bas comme ailleurs, les sectateurs du jazz « cool » ne se contentaient pas de piétiner les plate-bandes cultivées par les boppers. En Europe comme aux Etats-Unis, ils n’hésitaient pas à tendre une oreille en direction de l’atonalité, de la polytonalité, du dodécaphonisme, des formes classiques aussi et de l’écriture en général. Ce qui leur valut d’être montrés du doigt par les intégristes de tout poil. Les choses étant ce qu’elles sont, bien naturellement le jazz passa à autre chose – nombre de musiciens le fit également -, reléguant aux oubliettes les tentatives conduites durant une courte décennie. Qu’importe. Ce qui reste de cette musique, qu’elle soit due à Bobby Jaspar, Lars Gullin, Jean-Claude Fohren-bach, Henri Renaud, Jimmy Gourley, Sadi, Hans Koller, Gianni Basso ou bien d’autres, montre qu’ils eurent raison d’aller voir ailleurs si l’herbe était plus verte.

Alain Tercinet

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

(1) Henri Renaud, Le retour de Saturne, Jazz Magazine n° 521, décembre 2001.

(2) André Hodeir, Hommes et problèmes du jazz, Au Portulan, Flammarion, 1954.

(3) Lucien Malson, Henri Renaud ou l’épreuve de la réflexion, Jazz Magazine n° 69, avril 1961.

(4) Henri Renaud, Ce jazz que l’on appela cool, Cahiers du Jazz n°6, 1962.

(5) Bobby Jaspar parle du jazz moderne, Jazz Hot n° 96, février 1955.

(6) Bob Aubert et Bobby Jaspar, Stan Getz, Jazz Hot n° 56, juin 1951.

(7) Mark Myers, David Amram on Bobby Jaspar, JazzWax - internet.

(8) comme (5).

(9) Raymond Le Sénéchal « Modern Jazz in Paris » (LP Vogue LD 147).

(10) Fohrenbach Story, propos recueillis et mis en forme par Patrick Saussois, Jazz Swing Journal, n°3, mars/avril 1987.

(11) (12) The Lars Gullin Webside – Sessions by sessions, Internet. Il semble qu’une collaboration plus suivie ait été envisagée. Un projet réduit à néant par la mort de Dick Twardzick, le pianiste de Chet, par overdose. En 1959, ils se retrouveront en Italie, un DVD contient un extrait de concert commun donné au Teatro Alfieri de Turin.

(13) Chet Baker Talks to Pär Rittsel, The Lars Gullin Webside – Internet.

(14) Hans Elms , Roland Kovac , Jazz Hot n° 97, mars 1955.

(15) Joachim E. Berendt, Albert Mangelsdorff, Jazz Hot n° 97, mars 1955.

(16) Jutta Hipp émigra aux Etats-Unis puis abandonna la musique en 1958, ne pouvant supporter la pression liée là-bas à l’exercice du jazz. Bien qu’Hans Koller ait évolué du côté du Free Jazz (comme Attila Zoller, Albert Mangelsdorff et quelques autres) avant de se consacrer exclusivement à la peinture, son album Out on the Rim» signé en 1991 comprend un duo avec Warne Marsh et l’un des morceaux s’intitule In Memorium Stan Getz.

(17) Les séjours de Chet en Italie eurent un impact certain sur le jazz transalpin qui lui rendit volontiers hommage au travers de thèmes comme Dedicated to Chet écrit et interprété par Giancarlo Barigozzi et Chet to Chet de Gianni Basso qui, en 1998, gravera Chet’s Chum et Relaxin’ with Chet au sein du Civica Jazz Band. Quatre ans plus tard, Gianni Basso rendra aussi hommage de belle façon à l’un de ses anciens partenaires avec l’album « For Lars Gullin ».

N.B. Un certain nombre de morceaux provient de sources rares qui ont tant bien que mal traversé un demi-siècle. Que l’on veuille bien excuser leurs imperfections sonores particulièrement sensibles sur Venez donc chez moi. À propos de l’album enregistré par le sextette de Raymond Le Sénéchal - « Modern Jazz in Paris » (Vogue LD 147) - d’où ce morceau est tiré, Charles Delaunay, son producteur, dira en avoir vendu trente-cinq exemplaires… Une boutade proche de la vérité.

Merci à Pierre Carlu

EUROPEAN COOL JAZZ

The date was June 14th 1951, a Thursday, and the occasion was the “soiree jazz” held at the 3rd Cla-mart Music Festival. Numerous “old style” repre-sentatives had been invited – André Reweliotty, Eddie Bernard, Claude Bolling –, each fronting his own respective band, and Sidney Bechet had been announced on the bill but was absent as a result of a car accident; he was replaced at the last minute by Don Byas. Also on the bill was Henri Renaud’s sextet: it had two Americans who’d just arrived in Paris – tenor saxophonist Sandy Moss and guitarist Jimmy Gourley –, one Belgian, Bobby Jaspar, also a tenor player, and three Frenchmen, Pierre Michelot, Pierre Lemarchand, and Henri Renaud who said, “At that time we were the only ones in Paris playing music which mixed the influences of Charlie Christian and Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. In France, the Second World War had cut off all our relations with America, so when the Liberation came, we went abruptly from Django Reinhardt to Parker, ignoring the capital role played by Charlie Christian and Lester Young.” (1) Of the latter, André Hodeir said, “For a long time we thought that Lester Young had renovated the style of the tenor; in fact, it was a new jazz concept he caused to be born.” (2) Jimmy Gourley spread the word with a burning flame. “Thanks to him, I discovered the jazz I love. Without him I’d have certainly been unaware of Al Cohn, Tiny Kahn, Johnny Mandel and, hiding behind them, Lester and the Count.”(3) said Henri Renaud, fascinated by Al Haig then. Along with Sandy Mosse (an unconditional fan of Lester and Al Cohn), Bobby Jaspar (who admired Stan Getz and Warne Marsh), and Jimmy Gourley (a disciple of Jimmy Raney – the inventor of a new approach to the guitar inherited from Charlie Christian), Renaud would cause Parisians to discover a new form of modern jazz (hitherto quite unknown in France) and follow the trend that was then developing marginally in New York (and quite openly on the West Coast).

Thanks to the success of that sextet in Clamart, the band was given the opportunity to record a dozen sides for release on 78s. It was also a chance for the sextet to show where it stood at a time when “The jazz war was a reality; you had to choose sides,” as Renaud liked to remind people. When the (anonymous) reviewer at Jazz Hot had to deal with tunes like Godchild, Lady Be Bad and So What Could Be New?, he kicked for touch: the group played “cool”, its musicians were white, and so the “cool” style was to bop what Dixieland was to the music of New Orleans. Q.E.D.

“I hate the word ‘cool’. What does it really mean to use that label to group aesthetics as different as Lennie Tristano, the ‘Brothers’ and the style that dominated on the West Coast?” (4), wrote Henri Renaud later. He might just as well have added the Miles Davis Nonet to his list, the group responsible for the watershed in Bobby Jaspar’s playing: “It was when I heard ‘Boplicity’ that I quit the chemistry lab where I was working to concentrate on this music I finally thought was worthy of an exceptional aesthetic future.” (5)

Be that as it may. The term “cool” would remain, taking in this jazz which, for a whole decade, would in various doses absorb the contributions of the above-mentioned aesthetics, kneading them together to invent a new form of music at every occasion.

“…Henri acted as a modern-jazz innovator in France […] The style and its repertoire have now been adopted almost everywhere, but at that time you could only hear it at the Tabou, where Henri and his orchestra had a residency,” wrote Gérard Pochonet in his Jazz Hot review of “New Sounds from Belgium”, the first album recorded by Bobby Jaspar under his own name, and one which respected to the dot all the characteristics of the trend in which he intended to play a role: “The key qualities of these musicians are sobriety and a sort of musical dignity which, we believe, has caused them to be labelled ‘cool’: no noise just for the sake of noise, no romantic dithyrambs, no ‘hand-on-heart’ declarations… just enough of what it takes for it to swing and produce a maximum of music.” (6)

Under the title Tout Bleu, Tout Bleu, Jaspar plays Die Ganze Welt Ist Himmelblau from the operetta “White Horse Inn”. At first sight it seems an incongruous choice, but in fact it marks the distance he wanted to keep between himself and those who inspired him. According to Dave Amram, “Nearly every tenor saxophonist was influenced by Prez then. But Bobby took it in a different direction, melodically. It’s distinctly European, with France and Belgium as his points of reference.” (7)

It’s not the only example of someone having recourse to an unusual tune: Henri Renaud, fronting eleven musicians, served up a version – unexpected, to say the least – of Paris je t’aime, one of Maurice Chevalier’s great hits. Renaud conceived its arrangement with Francy Boland, a Belgian pianist/composer who was also the orchestrator of Don’t Touch the Grisbi, a piece which its composer Bernard Peiffer plays here with his “St Germain-des-Prés Orchestra”.

Boland was born in Namur, and Bobby Jaspar – the standard-bearer, catalyser and populariser of French “cool jazz” – came from Liège. Whatever would have happened without such Belgian reinforcements? There was René Thomas, Benoît Quersin, Christian Kellens – all three feature in Influence –, and also the irreplaceable Sadi who, fronting his band from the ‘Rose Rouge’, plays Big Balcony. The title was composed and arranged by Jaspar, in tribute to the glory of the “Grand Balcon” Hotel on the rue Dauphine where many jazzmen had chosen their quarters.

In Paris, Jaspar had partners available who were more than ready to bend to the discipline his music demanded. There was the pianist Maurice Vander, the trumpeter Roger Guérin – an ideal conversation-partner however audacious the experiment –, Jean-Louis Chautemps, William Boucaya, Armand Migiani, Jean-Louis Viale (Henri Renaud’s favourite drummer) and also Pierre Michelot, an immense bassist who was unjustly ignored as an arranger: his Jackie, My Little Cat tune was awarded the Hot Club de Paris Golden Jubilee Jazz Prize ahead of competitors from all over Europe.

Americans on their way through Paris also contributed to brighten up a number of record-sessions thanks to their talent and knowledge of the art: there was Buzz Gardner, trombonist/arranger Nat Peck, and horn-player David Amram, who was introduced to Jaspar by another temporary exile, baritone-player Jay Cameron; Bobby jumped at the chance to play with him. Occasion, written by Jaspar’s new partner, came along to perpetuate an entente that was anything but superficial.

As for Jay Cameron, he’d incorporated Jaspar into his “International Sax Band” alongside Barney Wilen and Jean-Louis Chautemps. The band’s aim was to pay homage, in its own way, to “The Brothers”, and its intentions earned such a roasting from Daniel Filipacchi (not Raymond Fol, as you might think from the signature) that Jay wrote an open letter to Jazz Magazine co-signed by twenty musicians. Blue Note here shows they were well within their rights.

Christian Chevallier played piano in the house-band at the Rose Rouge; he had a passion for composing and soon showed himself to be an exceptional arranger. After lending a hand to Henri Renaud for Marcel the Furrier, he took on all the other compositions – Bill Holman’s King Fish is one of them – which had the Jaspar/Amram duo facing off with Don Rendell, then the best cool tenor in Britain. With a prestigious Stan Kenton Prize in his bags, Chevallier was given the chance to make records of his own and, a rare occurrence, André Hodeir wrote the liner-notes for one of his albums, “6+6”: “Listen to ‘Les Rois Mages’ for exam-ple, where the theme first stated on the horn is ‘jazzed up’ a little, as if reached by the contagion of the backgrounds (or accompanying motifs) that finally constrain it, as it were, to express itself in a purely jazz form which it didn’t have at the beginning of the piece.” Hodeir went on to add, “Whatever else has been written about it, for the time being the experience of the Davis band’s arrangers still conditions the aesthetic of the chamber-orchestra in jazz.”

Who could have overtaken them in trying to go further? Bobby Jaspar had his own ideas: “I think I can claim that if a new evolution comparable to the one started by the Capitol session took place in France, we’d owe it to André Hodeir.” (8) It was “Bobby Jaspar’s New Jazz” that recorded Sanguine, a beautiful Henri Crolla tune used by Hodeir as a pretext for interlacing melody lines, and Jeux de quartes, one of Jaspar’s own arrangements which tried an incursion into twelve-tone music; it shows Jaspar’s keen interest in the research undertaken by the “Jazz Groupe de Paris” he cofounded with Hodeir. On a Blues is taken from “Essais”, the album which was the group’s birth-certificate, and it deals with the rapports that can be established between a simple orchestral riff evolving progressively and a blues improvisation played by Bobby Jaspar.

The last manifestation associated with these forays into territory rarely visited by jazz is Teanga, an original composition where Jaspar has himself accompanied by clarinet, flute, horn, oboe, bassoon, bass and drums. It was an uncommon line-up for the time, so experimental in fact that the album “Gone with the Winds” stayed swept under the carpet for eighteen months. It came out in autumn 1956 after Bobby had moved to the States, encouraged by the fact that he’d played in Paris with Chet Baker, whose visit had comforted the legitimacy of cool jazz.

Whereas Buzz Gardner, David Amram and Jay Cameron had all returned home across the water, like Chet Baker, other “tourists” came in as replacements: there was Allen Eager, a historic figure among modern tenors, who duelled in the Parisian studios with Scottish trumpeter Jimmy Deuchar; and also Billy Byers, a trombonist, composer and arranger who went to Paris early in 1956 at the invitation of Ray Ventura (by now a music-publisher rather than a bandleader.) Byers would stay almost two years; he was the eminence grise behind many sessions (including one led by Sacha Distel, an excellent guitarist and a regular guest with the Tabou’s band before partnering Bobby Jaspar at the Club Saint Germain). In the title On serait des chats you can hear him in the midst of a piano-less sextet whose sound is defined by the particular timbre of Jean Liesse’s trumpet together with the baritone (or bass clarinet) of William Boucaya. Three years earlier Sacha had taken part in a session led by Raymond Le Sénéchal, the man who’d become his regular pianist. Taken from that album now fallen into oblivion, Venez donc chez moi allows you to hear a talented, delicate clarinettist, Francis Weiss. (9)

As an instrumentalist, together with his trumpeter-compatriot Dickie Mills, Billy Byers would play Jaguar, a composition and arrangement signed by a newcomer on the Paris jazz scene: the pianist Martial Solal. His fundamental originality would make vain any and all attempts to attach him to a particular school.

The case of Jean-Claude Fohrenbach in the history of French cool jazz is unique. As Boris Vian’s partner and accomplice at the Club Saint Germain, and a man considered an excellent disciple of Coleman Hawkins, there came a point when he noticed that the way he played tenor was completely out of sync with his new compositions marked by his passion for Debussy, Ravel and Bartok: “So I found myself looking at a curious paradox: there was no room for me in MY music. So I looked for a ‘saxophonistic’ path that corresponded to the music I could hear, the music I was writing. I had to hear someone who already played like that. And it was very hard. It was a good thing this music didn’t stay marginal. As early as 1952 France discovered West Coast musicians like Stan Getz, Warne Marsh, Jimmy Giuffre etc… and I thought, ‘Hey, at last, guys who play like I do!’ It was quite the opposite of before, when I was trying to play like Hawkins. For sure, I wasn’t deaf, so I’d certainly been influenced by the West Coast, even in small doses, but I hadn’t been trying to play like them, it just happened that way.”(10) The idea of playing Le Chaland qui passe – a tune of Italian origin but successfully naturalized in France – resolved one of the issues facing “Fofo”, i.e. to build up a repertoire based on French standards.

Blue Smoke from Jack Dieval, Rêve played by William Boucaya, and Black Bottom from Armand Migiani’s Nonet, demonstrate the hold of the “cool” aesthetic over a whole vector of French jazz in this period, as did two albums by Bernard Zacharias, “Gershwin Parade” and “Cole Porter Parade”. Zacharias used to play trombone in Claude Luter’s orchestra, and before he teamed up with Henri Viard to transpose Hamlet as “L’Embrumé” in the detective-novel collection “La Série Noire”, he was regularly unfaithful to the “New Orleans Revival” (showing not many scruples, but always a lot of talent). So did André Persiany who, momentarily forgetting his obedience to “classical” jazz, wrote an arrangement with a lovely West Coast feel for this What Is This Thing Called Love?, which gives us the chance to hear the overlooked trumpeter Bernard Hulin and, hiding behind the pseudonym “Low Reed”, Michel de Villers on baritone.

On May 13th 1955, the Apollo hosted a concert by Henri Renaud’s All-Stars where they welcomed Lars Gullin, a Swedish-born baritone saxophonist, composer and arranger. Sweden was a country where the cool revolution in jazz happened quickly, albeit softly – this Shortly homage to Shorty Rogers is dated 1955 – with some components finding echoes in Swedish musical traditions (Ack Värmeland du Sköna, a folk tune cut in situ by Getz in 1951, slipped easily into the cool aesthetic under the title Dear Old Stockholm.) As for the music composed by Gullin himself – stamped with the bitter-sweet lyricism impregnating several forms of Swedish musical expression – Late Summer has something of the works of certain 19th century Scandinavian composers, and was even referred to as “Fäbodjazz”, a term which has folk/jazz blend allusions.

Gullin was a child-prodigy who was already playing the clarinet in a military band by the age of thirteen. He turned professional in 1947: “I had started to play the baritone in September 1949 and only six months later I stood in the studio with Zoot Sims. I was fresh on the instrument. My sound was raw because my mouth was dry from nervousness. But I did it my way and people told me it was OK.” (11) So did Zoot, the first American musician to hail him as a brother. Stan Getz and Lee Konitz joined in: “He’s got one of the nicest sounds, very much influenced by Gerry Mulligan with Miles Davis, that kind of a baritone sound that’s almost a tenor sound.” (12) In 1955 Gullin shared the bill at some concerts with Chet Baker, who paid him tribute several years later saying, “I was very impressed by him. He had a very melodic, liquid, yes a liquid way of moving through the changes, you know. Lars played with a lot more fire and a lot more authority in some ways than Gerry did.” (13)

Lars Gullin wasn’t the only one to incarnate the golden age of Swedish jazz then. There were a number of remarkable musicians: in Merlin and Fedja you can hear trombonist Åke Persson and the alto of Arne Domnerus, a Benny Carter disciple who assimilated the cool style with intelligence and didn’t go back on his support for it; Rolf Billberg in Late Summer; and clarinettist Putte Wickman in Meatballs, which was composed and arranged by Bengt Hallberg, who claimed the patronage of Tristano equally with that of Teddy Wilson and Bud Powell.

Lars Gullin was an immense musician, and his personal universe found itself in symbiosis with this cool trend which, as a result, he glorified as few others did. He toured widely in Europe in the Fifties, and notably in Germany where, in the middle of the decade, there was no shortage in the diatribes aimed at jazz (part of the legacy of National Socialism.) Not that they managed to dissuade any musicians from playing it. Swing had its supporters, others turned to the New Orleans Revival and, after a short period of adaptation, the new jazz had its adepts too, although they weren’t that many at the outset.

Marked by Warne Marsh, Lee Konitz and Zoot Sims, the tenor-player Hans Koller – an Austrian – quickly established himself as one of Europe’s most interesting saxophonists. He was also one of the boldest, especially in his exchanges with pianist (and composer) Roland Kovac, in whose opinion “The European listener, with a polyphonic tradition dating back a thousand years, is sufficiently educated to understand complex polyphonic forms.” (14) Listen to Iris and Passaglia, Variations n°8 where Lee Konitz and Lars Gullin join Hans Koller in a collective improvisation based on a passacaglia.

The first of Hans Koller’s quintets – here playing Unter Den Linden – included an exceptional musician named Albert Mangelsdorff, a man destined to become unavoidable in any talk of modern trombone. “He’s one of the very few original characters in the world of jazz. His style, apart from his incredible technical skills, is characterized by exceptional melodic freedom.” (15). Listening to Adlon 1925 confirms just how appropriate Leonard Feather’s words are.

Another partner Hans Koller chose was pianist Jutta Hipp. She was born in Leipzig and left East Germany so that she could continue playing her music. Highly influenced by Lennie Tristano, with whom she maintained a long correspondence, Jutta Hipp later formed her own group. It was close to the Tristano quintets, as much in spirit as in the choice of two saxophonists as its melody section: an alto, Emil Mangelsdorff, and a tenor, Joki Freund. Her band’s specificity lay in its repertoire of original tunes, with themes like Mon Petit, an extrapolation of I Never Knew, played here in front of an audience with beautiful tightness. (16) Their cohesive playing is a quality that could be legitimately claimed by the “Austrian All Stars” group created in 1954 by five musicians whose backgrounds lay in various dance-orchestras. The pianist was Joe Zawinul, the composer and arranger whose scores – Mekka, for example – sound strangely like what was being played in California then. It’s a long way from Cannonball Adderley and Weather Report.

Invited by the San Remo Jazz Festival in 1959, Lars Gullin spent some time in Italy where jazz had been opening up to all styles since the end of the war. This (unexpected) arrangement of Auld Lang Syne concocted by the excellent drummer Gil Cuppini shows that modern jazz was no dead end on the other side of the Alps, where there was any number of valua-ble musicians. Lars Gullin left numerous traces of his Italian stay in their company, meeting even Chet Baker again. (17)

Gullin recorded the remarkable Blues for Gassman with an octet led by the Basso-Valdambrini tandem; their pairing was a landmark in Italian jazz, having existed for almost forty years, most often in the form of a quintet. When Gianni Basso (a classy tenor-player then influen-ced by Stan Getz) and trumpeter Oscar Valdambrini invited valve-trombonist Dino Piana to join them, their group wasn’t far from the sextet of Gerry Mulligan: with But Not For Me they show they had little reason to envy him.

A year before Lars Gullin’s visit, Lee Konitz, accompanied by Renato Sellani, Franco Cerri and Gil Cuppini, had been in the studios to put Line in Sea in the can. And that was where it stayed. Eraldo Volontè gave him his revenge in Milan with his recording of Konitz in Italia, a title co-written by Konitz. In parallel, this time in Rome, the Modern Jazz Gang, banded together by Sandro Brugnolini, assembled alumni from the Junior Dixieland Gang which had been created to perpetuate the music of Bix Beiderbecke. The step they took was logical in that it led them towards cool jazz, and they gave their own very personal vision of it through a number of pieces, like this Arpo dedicated to critic Arrigo Polillo, or the remarkable suite Miles Before and After, which is too long to be included here.

We all know that the British don’t do anything like anyone else, and while foreign musicians were being welcomed with open arms everywhere, things were quite different in the United Kingdom. A decree from the “National Federation of Jazz Organizations of Great Britain and Northern Ireland” simply banned them from playing there, and the result of any transgression was that those responsible found themselves in court. And that was exactly what happened to those who, more or less on the sly, brought in first Coleman Hawkins, then Sidney Bechet. The decree was supposed to benefit the natives, but all it did was to preserve their splendid isolation. Those who begged to differ found a way out: since jazz couldn’t come to them, they would go to jazz. All they had to do was sign a contract with one of the orchestras plying their trade on the liners which cruised across the ocean to the USA.

Johnny Dankworth was employed aboard the “Queen Mary”, which is how this alto saxophonist, composer and arranger managed to hear Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie at Birdland, and make his acquaintance with the Miles Davis Nonet. As early as 1951, in echo of those experiences, Dankworth cut Leon Bismark, a tribute to Bix Beiderbecke, considered one of the spiritual fathers of cool jazz. On it you can hear Jimmy Deuchar, who was then quite marked by Miles Davis, and Don Rendell, a Prez disciple at the time who also shared the stage with Bobby Jaspar in Paris, the same year as he recorded Thames Walk with Ronnie Ross. Ross has probably been heard on baritone more often than anyone in the world (not that anyone has seen his name that much: he anonymously plays the introduction and solo on Lou Reed’s hit Walk on the Wild Side.) He owes that honour to the album’s producer, David Bowie, who remembered that when he was twelve years old – his name was still David Jones then – he’d taken saxophone lessons from him.

Vic Lewis had a solid friendship with Stan Kenton, which made him a natural intermediary between England and the West Coast. He’d had his own orchestra since 1946, with scores by the likes of Pete Rugolo, Bill Holman, Shorty Rogers and Bill Russo as regular items in his book. Or Gerry Mulligan, whose work had been sent to Lewis by Kenton; he even managed to record Blues in Riff before he did, under the title Hammersmith Riff. As if such manna from heaven was not enough, Vic Lewis had a few more Mulligan tunes orchestrated for his own use – Nights at the Turntable, Westwood Walk, Sextet, Bark for Barksdale – by arranger Johnny Keating, who’d remember it all three years later when he assembled the best that (Scottish) jazz had to offer for an album he called “Swinging Scots”, from which the Jimmy Deuchar composition Tam O’Shanter is taken.

Vic Lewis preferred formations with some substance, although when he went into the studios in March 1953 he was leading a lesser, experimental nonet which cut four very interesting pieces, among them this JD to VL written by Dankworth. In its ranks you can hear Kathleen Stobart on tenor, no doubt one of the very first female jazz players in Europe, historically speaking. Another British musician who (fleetingly) heard the seductive Sirens’ call – they called, “Cool” – is probably the best-known of those mentioned here due to the fame of the London jazz club which bears his name: tenor-player Ronnie Scott. Getting straight to the point, he borrows John Lewis’ tune S’il vous plaît from the Miles Davis Nonet.

In Britain, Sweden, Germany, Italy, France and Belgium, the “cool” wave washed over European jazz for a while. It also reached the shores of many other countries, as A Dandy Line might suggest (a Jack Montrose composition which Chet Baker recorded), here picked up in a Hilversum studio by drummer Wessel Ilcken, who’d met in Paris with Billy Byers and Martial Solal.

In such places, as elsewhere, “cool” jazz followers weren’t content to just tread on flower-beds sown by boppers. In Europe, as in The United States, they were quick to lend an ear to atonal music, polytonality, twelve-tone music, classical forms and the art of composition in general. All of which led fundamentalists of all sorts to point a finger at them. Things being what they are, jazz naturally moved on to something else – so did a number of musicians – condemning a short decade of experiment to oblivion. Not that it matters. What remains of that music, whether played by Bobby Jaspar, Lars Gullin, Jean- Claude Fohrenbach, Henri Renaud, Jimmy Gourley, Sadi, Hans Koller, Gianni Basso or many others, shows that they were right to go and see if the grass might indeed be greener on the other side.

Alain Tercinet

Adapted into English by : Martin DAVIES

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

(1) Henri Renaud, “Le retour de Saturne”, Jazz Magazine N° 521, December 2001.

(2) André Hodeir, “Hommes et problèmes du jazz”, Au Portulan, Flammarion, 1954.

(3) Lucien Malson, “Henri Renaud ou l’épreuve de la réflexion”, Jazz Magazine N° 69, April 1961.

(4) Henri Renaud, “Ce jazz que l’on appela cool”, Cahiers du Jazz N°6, 1962.

(5) “Bobby Jaspar parle du jazz moderne”, Jazz Hot N° 96, February 1955.

(6) Bob Aubert and Bobby Jaspar, “Stan Getz”, Jazz Hot N° 56, June 1951.

(7) Mark Myers, David Amram on Bobby Jaspar, JazzWax - Internet.

(8) as for (5).

(9) Raymond Le Sénéchal, “Modern Jazz in Paris”, (LP Vogue LD 147).

(10) “Fohrenbach Story”, observations gathered by Patrick Saussois, Jazz Swing Journal N°3, March/April 1987.

(11), (12) The Lars Gullin Website – Sessions by sessions, Internet. It seems they had plans to work more closely, but the project came to nothing when Dick Twardzik, Chet’s pianist, died after an overdose. In 1959 they got together again in Italy; a DVD has an excerpt from the concert they gave at the Teatro Alfieri in Turin.

(13) “Chet Baker Talks to Pär Rittsel”, The Lars Gullin Website – Internet.

(14) Hans Elms, “Roland Kovac”, Jazz Hot N° 97, March 1955.

(15) Joachim E. Berendt, “Albert Mangelsdorff”, Jazz Hot N° 97, March 1955.

(16) Jutta Hipp went to live in the USA and then abandoned music in 1958, unable to cope with the pressure surrounding jazz players there. Although Hans Koller moved in Free Jazz circles (like Attila Zoller, Albert Mangelsdorff and a few others) before devoting himself entirely to painting, his 1991 album “Out on the Rim” has a duet with Warne Marsh, and one of the pieces carries the title In Memoriam: Stan Getz.

(17) The visits Chet made to Italy had a definite impact on the jazz scene there, and musicians willingly paid tribute to him with tunes like Dedi-cated to Chet written and played by Giancarlo Barigozzi, and Chet to Chet by Gianni Basso who, in 1998, recor-ded Chet’s Chum and Relaxin’ with Chet with the Civica Jazz Band. Four years later, Gianni Basso would also pay a handsome tribute to an ex-partner with his album “For Lars Gullin”.

Note: A certain number of titles here come from rare sources, surviving, more or less successfully, over half a century. Please excuse their sound-imperfections (particularly noticeable in Venez donc chez moi.) As for the album recorded by the Raymond Le Sénéchal sextet – “Modern Jazz in Paris”, (Vogue LD 147) – from which the title is taken, its producer Charles Delaunay said that he sold thirty-five copies… a quip probably not far from the truth.

Thanks to Pierre Carlu

EUROPEAN COOL JAZZ – CD 1

1. HENRI RENAUD ALL STARS : PARIS, JE T’AIME (C. Grey, H. Bataille, V. Schertzinger) mx 53V4511 - Vogue LD131 4’10

2. BOBBY JASPAR with THE HENRI RENAUD QUINTET : TOUT BLEU, TOUT BLEU (R. Gilbert, R. Stolz) Unnumbered - Vogue LD 143 3’43

3. BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : SANGUINE (H. Crolla) Unnumbered - Swing M33338 2’36

4. BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : JEUX DE QUARTES (B. Jaspar) Unnumbered - Swing M33338 2’33

5. BOBBY JASPAR JOUE HENRI RENAUD : MARCEL THE FURRIER (H. Renaud) mx 54V4987 - Vogue EPL7100 2’13

6. JAZZ GROUPE DE PARIS : ON A BLUES (A. Hodeir) Unnumbered - Swing M33353 4’02

7. BOBBY JASPAR AND THE WOODWINDS : TEANGA (B. Jaspar) mx 55V5173 - Swing M33351 3’52

8. DAVID AMRAM/BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET : OCCASION (D. Amram) Unnumbered - Swing M33355 2’49

9. DON RENDELL & BOBBY JASPAR : KING FISH (B. Holman) Unnumbered - Swing M33344 3’33

10. BERNARD PEIFFER AND HIS ST GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS ORCHESTRA : DON’T TOUCH THE GRISBI (B. Peiffer) Unnumbered - Blue Star BS6842 2’04

11. FATS SADI AND HIS COMBO : BIG BALCONY (B. Jaspar) Unnumbered - Vogue LD212 3’33

12. FOHRENBACH FRENCH SOUND : LE CHALAND QUI PASSE (E. Neri, C. A. Bixio, A. de Badel) mx MA2602 - Pacific A08 2’45

13. ARMAND MIGIANI NONET : BLACK BOTTOM (B. G. de Sylva, L. Brown, R. Henderson) Unnumbered - Polydor 20704 3’13

14. KENNY CLARKE & HIS ORCHESTRA : JACKIE MY LITTLE CAT (P. Michelot) mx 7XCL 5862 - Columbia ESDF 1176 3’26

15. JAY CAMERON’S INTERNATIONAL SAX BAND : BLUE NOTE (J. van Rooyen) Unnumbered - Swing M33341 3’09

16. HENRI RENAUD SEXTET : INFLUENCE (H. Renaud) Unnumbered - Vogue EPL7177 3’36

17. CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ORCHESTRA : LES ROIS MAGES (C. Chevallier) Unnumbered - Columbia ESDF 1244 3’29

18. JAZZ ON THE LEFT BANK : JAGUAR (M. Solal) Unnumbered - Philips BO8112L 2’46

19. SACHA DISTEL : ON SERAIT DES CHATS (B. Byers) Unnumbered - Versailles 2010 3’03

20. BERNARD ZACHARIAS & SES SOLISTES : WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE ? (C. Porter) Unnumbered - Club Français du Disque 78 3’32

21. RÉUNION À PARIS : ILLUSION (M. Solal) Unnumbered - Swing LDM 30.048 3’16

22. JACK DIEVAL’S ALL STARS : BLUE SMOKE (C. Chevallier) Unnumbered - Ducretet-Thompson 250 V 001 2’47

23. WILLIAM BOUCAYA & HIS NEW SOUND SEXTET : RÊVE (H. Rostaing) Unnumbered - Ducretet-Thompson 250 V 001 2’49

24. RAYMOND LE SÉNÉCHAL SEXTET : VENEZ DONC CHEZ MOI (J. Féline, P. Misraki) Unnumbered - Vogur LD 147 3’07

1. HENRI RENAUD ALL STARS : Jean Liesse (tp) ; Benny Vasseur (tb) ; Georges Barboteu (frh) ; Sandy Mosse, André Ross (ts) ; William Boucaya, Jean-Louis Chautemps (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean Louis Viale (dm) ; Francy Boland, Henri Renaud (arr) – Paris, april 10, 1953.

2. BOBBY JASPAR with THE HENRI RENAUD QUINTET : Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, may 22, 1953.

3. BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : Roger Guérin, Buzz Gardner (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (as) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Armand Migiani (bs) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; André Jourdan (dm) ; André Hodeir (arr) – Paris, october 12, 1954.

4. BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ : Roger Guérin, Buzz Gardner (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (b-cl) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Armand Migiani (bs) ; « Fats » Sadi Lallemand (vib) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Gérard « Dave » Pochonnet (dm) – Paris, october 14, 1954.

5. BOBBY JASPAR JOUE HENRI RENAUD : Roger Guérin (tp) ; Buzz Gardner (flh) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) ; Christian Chevallier (arr) – Paris, november 15, 1954.

6. JAZZ GROUPE DE PARIS : Jean Liesse, Buzz Gardner (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (as) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Armand Migiani (bs) ; « Fats » Sadi Lallemand (vib) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jacques David (dm) ; André Hodeir (arr, cond) – Paris, december 13, 1954.

7. BOBBY JASPAR PLAYS : Dave Amram (frh) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Jean-Louis Chautemps (cl) ; Raymond Lefebvre (fl) ; Claude Foray (oboe) ; Emile Debru (basson) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jacques David (dm) – Paris, april 20, 1955.

8. DAVID AMRAM/BOBBY JASPAR : David Amram (frh) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Eddie de Haas (b) ; Jacques David (dm) – Paris, july 4/5, 1955.

9. DON RENDELL & BOBBY JASPAR : Dave Amram (frh) ; Bobby Jaspar, Don Rendell (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Guy Pedersen (b) ; Jean-Baptiste «Mac Kac » Reilles (dm) ; Christian Chevallier (arr) – Paris, march 17, 1955.

Solos : Jaspar, Distel, Amram, Rendell, 4/4 Jaspar - Rendell.

10. BERNARD PEIFFER AND HIS ST GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS ORCHESTRA : Roger Guérin (tp, tuba alto) ; Bobby Jaspar, Bib Monville (ts) ; Bernard Peiffer (p) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Baptiste «Mac Kac » Reilles (dm) ; Francy Boland (arr) – Paris, january 14, 1954.

11. FATS SADI’S COMBO : Roger Guérin (tp, tuba alto) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (b-cl) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; « Fats » Sadi Lallemand (vib) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, may 8, 1954.

12. FOHRENBACH FRENCH SOUND : Jean-Claude Fohrenbach (ts, arr) ; Louis Aldebert (p) ; Henri Cerri (g) ; Henri « Ricky » Garzon (b) ; Japy Gauthier (dm) - Paris, 1954.

13. ARMAND MIGIANI NONET : Christian Bellest, Roger Guérin (tp) ; Charles Verstraete (tb) ; William Boucaya (as) ; Georges Grenu (ts) ; Armand Migiani (bs, arr) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Roger Paraboschi (dm) – Paris, may 1956.

14. KENNY CLARKE & HIS ORCHESTRA : Bernard Hulin, Ack van Rooyen (tp) ; Nat Peck, Billy Byers (tb) ; Hubert Fol (as) ; Lucky Thompson, Pierre Gossez (ts) ; Armand Migiani (bs) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b, arr) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) – Paris, september 23, 1957.

15. JAY CAMERON’S INTERNATIONAL SAX BAND : Bobby Jaspar, Jean-Louis Chautemps, Barney Wilen (ts) ; Jay Cameron (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean-Baptiste «Mac Kac » Reilles (dm) – Paris, january 10, 1955.

Solos : Cameron, Jaspar, Wilen, Chautemps.

16. HENRI RENAUD SEXTET : Christian Kellens (tb) ; Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p, arr) ; René Thomas (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jacques David (dm) – Paris, june 9, 1955.

17. CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ORCHESTRA : Ack van Rooyen (tp) ; Roger Guérin (flh) ; George Barboteu (cor) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jo Hrasko (as) ; Georges Grenu (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Armand Migiani (bass-s) ; Michel Hauser (vib) ; Pierre Cullaz (g) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) ; Christian Chevallier (arr) – Paris, november 8/26, 1957.

18. JAZZ ON THE LEFT BANK : Dick Mills (tp) ; Billy Byers (tb) ; William Boucaya (bs, ts) ; Martial Solal (p, arr) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Wes Ilcken (dm) – Paris, september 13-16, 1956.

19. SACHA DISTEL : Jean Liesse (tp) ; Billy Byers (tb, arr) ; Georges Grenu (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs, b-cl) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) – Paris, june 1-2, 1956.

20. BERNARD ZACHARIAS & SES SOLISTES : Bernard Hulin (tp) ; Bernard Zacharias, Sandy Fall (tb) ; José Germain, Teddy Hameline (as) ; André Dabonville, Armand Conrad (ts) ; Low Reed (aka Michel de Villers (bs) ; Jules Dupont (aka André Persiany) (p, arr) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Roger Paraboschi (dm) – Paris, 1956.

21. RÉUNION À PARIS : Jimmy Deuchar (tp) ; Billy Byers (tb) ; Allen Eager (ts) ; Martial Solal (p, arr) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) – Paris, september 24, 1956.

22. JACK DIEVAL’S ALL STARS : Fernand Verstraete (tp) ; Benny Vasseur (tb) ; Maurice Meunier (cl) ; Jean-Claude Fohrenbach (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Jack Diéval (p, arr) ; Géo Daly (vib) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Bernard Planchenault (dm) – Paris, prob. 1954.

23. WILLIAM BOUCAYA & HIS NEW SOUND SEXTET : Christian Bellest (tp) ; Georges Barboteu (frh) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Arthur Motta (dm) – Paris, prob. 1954.

24. RAYMOND LE SÉNÉCHAL SEXTET : Francis Weiss (cl) ; Raymond Le Sénéchal (p, arr) ; « Fats » Sadi Lallemand (vib) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Marcel Dutrieux (b) ; Jean-Baptiste «Mac Kac » Reilles (dm) – Paris, june 1, 1953.

EUROPEAN COOL JAZZ – CD 2

1. LARS GULLIN & HIS BAND : MERLIN (L. Gullin) mx 418 - Metronome JLP 23 3’32

2. CARL-HENRIK NORIN ORKESTER : SHORTLY (R. Öfwerman) Unnumbered - HMV 7EGS 35 2’56

3. LARS GULLIN OCTET : FEDJA (L. Gullin) mx 1037A-3 - Metronome MEP 196 5’03

4. BENGT HALLBERG ENSEMBLE : MEATBALLS (B. Hallberg) mx KS119 - Pacific Jazz EP4-17 3’22

5. LARS GULLIN SEXTET : LATE SUMMER (L. Gullin) mx 882 - Metronome MEP 129 5’2

6. HANS KOLLER’S NEW JAZZ STARS with Lars Gullin & Lee Konitz : PASSAGLIA, VARIATIONS n°8 (R. Kovac) Unnumbered - Carisch LCA 29011 3’02

7. HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : UNTER DEN LINDEN (H. Koller) Unnumbered - Vogue LD 144 2’56

8. HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : IRIS (R. Kovac) Unnumbered - Amadeo AVRS7013 4’10

9. JUTTA HIPP QUINTET : MON PETIT (J. Hipp) Unnumbered - Brunswick 8601LPB 3’14

10. ALBERT MANGELSDORFF UND SEINE FRANKFURT ALL STARS : ADLON 1925 (A. Mangelsdorff) Unnumbered - Jazztone J1246 2’27

11. THE AUSTRIAN ALL STARS : MEKKA (J. Zawinul) W8501 - Austroton EPA 1030 2’14

12. GIL CUPPINI E IL SUO COMPLESSO : AULD LANG SYNE (trad.) OBA 8771 - La Voce Del Padrone HN3381 2’57

13. ERALDO VOLONTÈ E IL SUO QUINTETTO : KONITZ IN ITALY (L. Konitz, F. Nicoli) Unnumbered - Astraphon LPA10001 3’09

14. MODERN JAZZ GANG : ARPO (S. Brugnolini) Unnumbered - Astraphon PLA 10001 4’53

15. BASSO-VALDAMBRINI OCTET : BLUES FOR GASSMAN (P. Umiliani) Unnumbered - Jolly LPJ 5007 2’49

16. BASSO-VALDAMBRINI QUINTET plus DINO PIANA : BUT NOT FOR ME (I. & G. Gershwin) Unnumbered - Jolly LPJ 5010 3’19

17. THE WESSEL ILCKEN COMBO : A DANDY LINE (J. Montrose) Unnumbered - Philips FI17415H 2’48

18. JOHNNY DANKWORTH SEVEN : LEON BISMARK (J. Dankworth) mx 210 - Esquire 10-173 3’28

19. VIC LEWIS NEW MUSIC : JD TO VL (J. Dankworth) mx 285 - Esquire 10-232 3’33

20. RONNIE SCOTT JAZZ GROUP : S’IL VOUS PLAÎT (J. Lewis) mx 746 - Esquire EP-81 2’31

21. DON RENDELL SEXTET : THAMES WALK (D. Hawdon) mx VOG39 - Tempo A108 2’53

22. JOHNNY KEATING AND HIS ALL-STARS : TAM O’SHANTER (J. Deuchar) Unnumbered - Dot DLP 3066 4’36

1. LARS GULLIN & HIS BAND : Arnold Johansson (tp) ; Åke Person (tb) ; Åke Björkman (frh) ; Arne Domnerus (as) ; Lars Gullin (bs) ; Gunnar Svensson (p) ; Yngve Akerberg (b) ; Jack Norén (dm) - Stockholm, december 12, 1952.

2. CARL-HENRIK NORIN ORKESTER (Dom röda banditerna) : Jan Allan (tp) ; Bo Magnusson (as) ; Carl-Henrik Norin (ts) ; Rune Falk (bs) ; Jan Boquist (p) ; Lasse Pettersson (b) ; Gunnar Nyberg (dm) ; Rune Ofwerman (arr) - Stockholm, may 25, 1955.

3. LARS GULLIN OCTET : George Vernon (tb) ; Arne Domnerus (as) ; Carl-Henrik Norin (ts) ; Lars Gullin, Rune Falk (bs) ; Rune Öfwerman (p) ; Georg Riedel (b) ; Nils-Bertil Dahlander (dm) – Stockholm, april 23, 1956.

4. BENGT HALLBERG ENSEMBLE : Åke Persson (tb) ; Putte Wickman (cl) ; Lars Gullin (bs) ; Bengt Hallberg (p,arr) ; Simon Brehm (b) ; Robert Edman (dm) - Stockholm, january 18, 1954.

5. LARS GULLIN SEXTET : Rickard Brodén (Johansson) (tb) ; Rolf Billberg (ts) ; Lars Gullin (bs) ; Rolf Berg (g) ; Georg Riedel (b) ; William Schiøpffe (dm) - Stockholm, june 13, 1955.

6. HANS KOLLER’S NEW JAZZ STARS with Lars Gullin & Lee Konitz : Lee Konitz (as) ; Hans Koller (ts) ; Lars Gullin (bs) ; Johnny Fischer (b) ; Karl Sanner (dm) – Köln, january 21, 1956.

7. HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : Albert Mangelsdorff (tb) ; Hans Koller (ts) ; Jutta Hipp (p) ; Shorty Raeder (b) ; Karl Sanner (dm) – Baden Baden, May 1953.

8. HANS KOLLER NEW JAZZ STARS : Hans Koller (ts) ; Willi Sanner (bs) ; Roland Kovac (p); John E. Fisher (b) ; Rudi Sehring (perc) – Vienna, december 6, 1955.

9. JUTTA HIPP QUINTET : Emil Mangelsdorff (as) ; Joki Freund (ts) ; Jutta Hipp (p) ; Hans Kresse (b) ; Karl Sanner (dm) – Deutsche Jazz Festival, Frankfurt, june 6, 1954.

10. ALBERT MANGELSDORFF UND SEINE FRANKFURT ALL STARS : Albert Mangelsdorff (tb); Emil Mangelsdorff (as) ; Hans Koller (ts, bs, cl) ; Joki Freund (ts) ; Pepsi Auer (p) ; Peter Trunk (b) ; Rudi Schring (dm) – Frankfurt, june 1-2, 1958.

11. THE AUSTRIAN ALL STARS : Hans Salomon (as) ; Karl Drewo (ts) ; Joe Zawinul (p, arr) ; Rudolf Hansen (b) ; Viktor Plasil (dm) – Vienna, october 18, 1954.

12. GIL CUPPINI E IL SUO COMPLESSO : Mario Midana (tp) ; Giancarlo Barigozzi (as) ; Eraldo Volontè (ts) ; Sandro Bagalini (bs) ; Silvio Comensoli (vib) ; Gianfranco Intra (p) ; Antonio De Serio (b) ; Gilberto Cuppini (dm, arr) – Milano, september 8, 1954.

13. ERALDO VOLONTÈ E IL SUO QUINTETTO : Sergio Fanni (tp) ; Eraldo Volontè (ts) ; Renato Angiolini (p) ; Alceo Guatelli (b) ; Lionello Bionda (dm) – Milano, february 19, 1959.

14. MODERN JAZZ GANG : Cicci Santucci (tp) ; Alberto Collatina (v-tb) ; Sandro Brugnolini (as, ldr) ; Carlo Metallo (bs) ; Leo Cancellieri (p) ; Sergio Biseo (b) ; Roberto Podio (dm) – Roma, january 26, 1959.

15. BASSO-VALDAMBRINI OCTET : Oscar Valdambrini (tp) ; Mario Pezzotta (tb) ; Glauco Masetti (as) ; Gianni Basso (ts) ; Lars Gullin (bs) ; Renato Sellani (p) ; Franco Cerri (b) ; Jimmy Pratt (dm) ; Piero Umiliani (arr) – Milano, december 10,17, 21, 23 , 1959.

16. BASSO-VALDAMBRINI QUINTET PLUS DINO PIANA : Oscar Valdambrini (tp) ; Dino Piana (v-tb) ; Gianni Basso (ts) ; Renato Sellani (p) ; Giorgio Azzolini (b) ; Gianni Cazzola (dm) – Milano, april 29, may 2 & 10, 1960.

17. THE WESSEL ILCKEN COMBO : Jerry van Rooyen (tp, arr) ; Dick Bezemer (tb) ; Toon van Vliet (ts) ; Chris Bender (b) ; Wessel Ilcken (dm) – Hilversum, january 17, 1955.

18. JOHNNY DANKWORTH SEVEN : Jimmy Deuchar (tp) ; Eddie Harvey (tb) ; John Dankworth (as, cl) ; Don Rendell (p) ; Bill Le Sage (p) ; Eric Dawson (b) ; Tony Kinsey (dm) – London, july 12, 1951.