- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

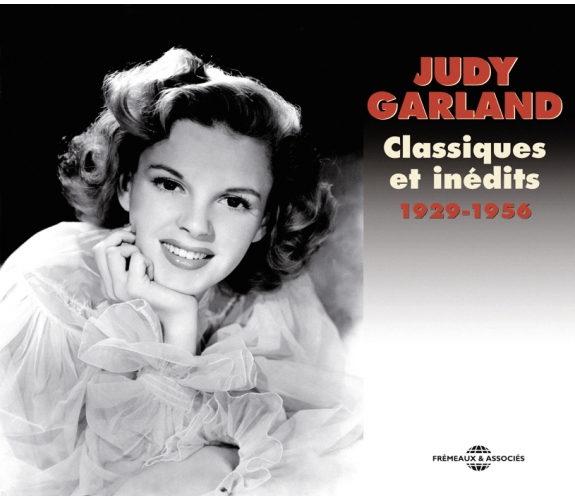

CLASSIQUES ET INEDITS 1929 - 1956

Ref.: FA5184

EAN : 3561302518428

Direction Artistique : LAWRENCE SCHULMAN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 1 heures 52 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

CLASSIQUES ET INEDITS 1929 - 1956

Artiste légendaire d’Hollywood, Judy Garland a marqué l’ensemble de la création artistique américaine du milieu du XXe siècle : le cinéma, la scène, la radio et la chanson. Son inégalable "Over the Rainbow" a été élu « chanson du siècle » et cinq de ses enregistrements sont entrés au Grammy Hall of Fame.

Lawrence Schulman propose ici une anthologie exceptionnelle pour tous publics avec un premier disque composé des plus grands titres de Judy Garland et un second réunissant des inédits discographiques en provenance de collections privées – dont la rareté excusera une qualité sonore inférieure aux enregistrements studio. Un nouvel éclairage sur l’icône intemporelle d’un âge d’or mythique de l’Amérique.

Patrick Frémeaux

Classiques : Blue Butterfly • Hang On To A Rainbow • Stompin’ At The Savoy • Over The Rainbow • I’m Just Wild About Harry • But Not For Me • Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas • On The Atchison, Topeka And The Santa Fe • Who ? • You Can Do No Wrong • I Wish I Were In Love Again • Better Luck Next Time • Get Happy • Send My Baby Back To Me • Heartbroken • Without A Memory • Go Home, Joe • The Man That Got Away • Judy at the Palace • Memories of You - Inédits : Broadway Rhythm • Zing! Went The Strings Of My Heart • On Revival Day • Smiles • My Heart Is Taking Lessons • On The Bumpy Road To Love • Swing Low, Sweet Chariot • Goody Goodbye • In Spain They Say “Si-Si” • Love’s New Sweet Song • The Things I Love • Daddy • Minnie From Trinidad • That Old Black Magic • Over The Rainbow • Embraceable You/The Man I Love • Somebody Loves Me • Someone To Watch Over Me • Love • You And I.

Droits : Groupe Frémeaux Colombini - Variétés Internationales.

NEW YORK - HOLLYWOOD 1939-1955

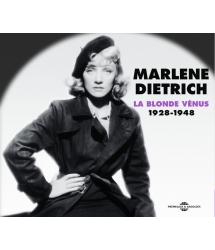

LA BLONDE VENUS 1928 - 1948

FASCINATING RHYTHM - 100ème ANNIVERSAIRE

Live in Paris – 1960

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Blue ButterflyGarland Judy00:02:021929

-

2Hang On To The RainbowGarland Judy00:01:091929

-

3Stompin' At The SavoyGarland Judy00:02:271936

-

4Over The RainbowGarland Judy00:02:151938

-

5I'm Just Wild About HarryGarland Judy00:02:041939

-

6But Not For MeGarland Judy00:03:151943

-

7Have Yourself A Merry Little ChristmasGarland Judy00:02:471944

-

8On The Atchison Topeka And Santa FeGarland Judy00:03:161945

-

9WhoGarland Judy00:02:511945

-

10You Can Do No WrongGarland Judy00:03:051947

-

11I Wish I Were In Love AgainGarland Judy00:02:481947

-

12Better Luck Next TimeGarland Judy00:03:041948

-

13Get HappyGarland Judy00:02:521950

-

14Send My Baby Back To MeGarland Judy00:02:121953

-

15HeartbrokenGarland Judy00:02:421953

-

16Without A MemoryGarland Judy00:02:501953

-

17Go Home JoeGarland Judy00:03:051953

-

18The Man That Got AwayGarland Judy00:03:411953

-

19Judy At The PalaceGarland Judy00:06:191955

-

20Memories Of YouGarland Judy00:03:381956

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Broadway RhythmGarland Judy00:03:571935

-

2Zing When The Strings Of My HeartGarland Judy00:03:351935

-

3On Revival DayGarland Judy00:03:021936

-

4SmilesGarland Judy00:02:521937

-

5My Heart Is Taking LessonsGarland Judy00:02:171938

-

6On The Bumpy Road To LoveGarland Judy00:02:311938

-

7Swing Low Sweet ChariotGarland Judy00:01:521938

-

8Goody GoodbyeGarland Judy00:02:261939

-

9In Spain They Say Si SiGarland Judy00:02:211940

-

10Love's New Sweet SongGarland Judy00:01:131941

-

11The Things I LoveGarland Judy00:02:261941

-

12DaddyGarland Judy00:02:181941

-

13Minnie From TrinidadGarland Judy00:03:531942

-

14That Old Black MagicGarland Judy00:02:371943

-

15Over The RainbowGarland Judy00:04:161943

-

16Embraceable YouGarland Judy00:04:151943

-

17Somebody Loves MeGarland Judy00:01:071944

-

18Someone To Watch Over MeGarland Judy00:02:421944

-

19LoveGarland Judy00:03:271945

-

20You And IGarland Judy00:01:271951

Judy Garland

Judy Garland

Classiques et inédits

1929-1956

Plus on pense connaître Judy Garland (1922-1969), plus on se rend compte qu’on n’en connaît rien. Il n’existe pas d’experts en la matière. Elle est une énigme grandiose. On la trouve partout et nulle part pendant sa trop courte existence. Indéfinie et indéfinissable, elle papillonne d’un film à l’autre, d’une séance d’enregistrement à l’autre, d’un concert de par le monde à l’autre. Le public l’applaudit et l’adore jusqu’à ce que les mains, le cœur et la patience n’en puissent plus. C’est un « entertainer », mais les jours jalonnés de pilules et les nuits sans sommeil en font un être solitaire, qui téléphone à ses amis à n’importe quelle heure, qui joue au billard à Times Square au milieu de la nuit. Plus que solitaire, elle est seule. Maris, amis et admirateurs, tous sont impuissants à sauver l’esprit errant qui carbure au désordre, et en même temps s’en moque. Elle s’étiole sous les sobriquets de « vilain petit canard » et « petit bossu » dont les patrons de studio l’affublent dans sa jeunesse; sous le poids d’être une enfant-prodige alors qu’on ne lui a jamais demandé si elle veut faire du spectacle; de par la perte de son père, victime de la méningite quand elle a treize ans, « la pire chose qui [lui] soit arrivée », rappelle-t-elle. Bien plus tard, elle chantera qu’elle est « née pour l’errance » (born to wander), mais sa prononciation du haut Midwest de wander ressemble à wonder (s’interroger). L’errance sans but rejoint les questions sans réponses, et la route sera rude, le voyage de courte durée, et le quotidien souvent indigne. En dépit de tout, il y a sa voix : généreuse, chaleureuse, naturelle. Contralto à registre peu étendu, elle pousse, s’il le faut, jusqu’au do aigu ou mi bémol grave. Son vibrato dépend de sa condition physique ou émotionnelle. Elle ne sait pas improviser. Sa respiration va du robuste, sans inspirer là où d’autres chanteurs en ont besoin, au passable, quand elle est trop maigre et à bout de nerfs. Elle ne souligne pas toujours les voyelles, mais insiste sur les consonnes finales. Elle sait chanter le swing dès le début de sa carrière, comme quelque chose d’imposé par l’époque, mais ce n’était pas naturel chez elle. L’émotion brute qu’elle projetait se prêtait plus à la variété qu’au jazz. Cependant, ses très rares tentatives dans un style jazzy tout au long de sa carrière laissent l’auditeur bouche bée, au point où l’on s’interroge sur ce qu’elle aurait pu devenir si, comme Peggy Lee ou Frank Sinatra, elle avait démarré comme chanteuse dans un big band. Dès ses premières apparitions, elle a du coffre. Sa voix, ample comme à l’opéra, s’amplifiera encore avec l’âge. Faire trembler les vitres à la Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer ou au Metropolitan Opera de New York est un jeu d’enfant. Le chant s’enchaîne à la parole sans hiatus, et cette faculté innée contribue à son naturel au cinéma. Elle a, avant tout, une sincérité qui crève l’écran. L’auditoire est conquis et se cramponne à chacune de ses notes. Le sens émane des paroles, mais pas seulement. Chaque syllabe, chaque silence, chaque inspiration pousse le public au bord de son siège. Elle captive l’auditeur en s’adressant directement à lui. Pour certains ce n’est plus, à ce niveau, du spectacle, mais de l’art.

La voix survit, mais Judy Garland n’a vécu que quarante-sept petites années. Née le 10 juin 1922 à Grand Rapids (dans le Minnesota) d’Ethel et Frank Gumm, Frances Ethel Gumm, ainsi nommée, est la benjamine de trois filles. Les sœurs Gumm – Mary Jane (surnommée Suzy), l’aînée, Virginia (surnommée Jimmy), et Frances « Baby » Gumm – deviennent les Gumm Sisters au temps du vaudeville alors qu’elles jouent au New Grand Theater de leur père. Ethel, la mère typique d’enfants-acteurs, est au piano. En ce temps où l’on monte des numéros mettant en scène des enfants, Ethel et Frank forment une famille du spectacle, poussant leurs filles de bonne heure vers le vaudeville. Ethel réalise le potentiel artistique et financier des sœurs, surtout celui de Frances, que le talent distingue déjà et qui fait la fierté de Frank. « Baby » Gumm interprète son premier solo dans le théâtre paternel en 1925, lorsqu’elle chante Jingle Bells à un public sidéré. L’excitation et l’aura chaleureuse de cet instant-là vont l’accompagner toute sa vie. A vrai dire, Grand Rapids tout entier l’accompagnera toujours. La vie douillette dans une petite ville à la Norman Rockwell restera un souvenir baigné d’affection. On la voit sur des photographies d’archive, assise jouant sur la pelouse devant la petite maison blanche familiale, le foyer idyllique. Moments de bonheur dans des souvenirs immaculés, qui lui sont dérobés lorsqu’Ethel emmène les trois soeurs en tournée. Ethel ne cherche probablement qu’à joindre les deux bouts. Cependant, elle fait aussi passer son intérêt devant celui de ses filles. Des rumeurs courent sur les infidélités de Frank – des aventures homosexuelles qui plus est. Les filles ont dû entendre leurs parents se disputer. Ethel veut mettre tout cela derrière elle, et pour ce faire la tournée est un bon moyen. La jeune Frances adore la scène mais abhorre quitter Grand Rapids et l’affection de son père. Elle nourrit sa passion aux feux de la rampe et s’y brûle en même temps. Cette dualité va la ronger toute sa vie. Fin 1926, les Gumm déménagent pour Lancaster en Californie, où Frank a acquis et dirige le Lancaster Theater. C’est la fin du rêve. Les Gumm Sisters se rapprochent de Hollywood, Ethel peut les faire engager dans le vaudeville et Frank peut repartir à zéro. Lancaster – ville poussiéreuse à environ trois heures en voiture de Los Angeles – n’a cependant rien de Grand Rapids et sonne la fin de la jeunesse innocente pour Frances. Les Sisters se produisent assez régulièrement sur la côte ouest, jusque sur les stations de radio locales. En cette période charnière entre les cinémas muet et parlant, les groupes musicaux sont très prisés, et les Gumm Sisters sont engagées par Mayfair Pictures pour chanter That’s the Good Old Sunny South dans un court-métrage, The Big Revue, filmé en juin 1929 aux Tec-Art Studios à Hollywood. Peu de temps après, elles commencent à se produire avec les Meglin Kiddies sur scène et à l’écran, et tournent trois courts-métrages en novembre et décembre 1929 pour First National-Vitaphone Pictures – A Holiday in Storyland, The Wedding of Jack and Jill, et Bubbles –, dans lesquels Frances chante pour la première fois seul à l’écran Blue Butterfly (I, 1) et Hang on to a Rainbow (I, 2).

Leur chance se présente en 1934. En juillet, les filles sont engagées à l’Exposition Universelle de Chicago, puis à l’Oriental Theatre en août, où la tête d’affiche George Jessel, exaspéré de les voir affichées comme les Gum Sisters (les Sœurs Gencives), les Gun Sisters (les Sœurs Canons) et les Glumm Sisters (les Sœurs Fadasses), les présente pour la première fois comme les Garland Sisters, d’après le critique dramatique new-yorkais Robert Garland. En mars 1935, le trio, avec Ethel au piano, enregistre trois disques d’essai pour Decca – Moonglow, Bill (où Frances chante seule) et un pot-pourri de On the Good Ship Lollipop/The Object of My Affection/Dinah – mais les trois sont rejetés. Le tournant de la vie de Judy Garland advient quand les Gumm/Garland Sisters apparaissent au Cal-Neva Lodge de Lake Tahoe l’été de la même année. Frances a déjà décidé de s’appeler Judy, d’après la chanson homonyme de l’époque écrite par Hoagy Carmichael. L’agent de spectacle Al Rosen, accompagné du compositeur Harry Akst, tombe sur the trio lors de leur dernière soirée, et après la représentation demande à Judy de chanter Dinah, écrite by Akst, qui l‘accompagne. Tous deux restent stupéfaits, et Rosen se met à faire le tour de Hollywood. A l’âge intermédiaire de 13 ans, Judy est difficile à caser. Enfin, Rosen lui décroche une audition à la MGM le 13 septembre, et devant Louis B. Meyer elle chante avec force Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart et Eili, Eili. Judy Garland signe un contrat avec la MGM le 16 septembre 1935. Invitée deux fois à l’émission radiophonique The Shell Chateau dans les studios de KFI à Los Angeles suivant son embauche, Judy claironne Broadway Rhythm (II, 1) et Zing! (II, 2), et fait sensation. Une fois encore, Decca la remarque, et lui demande en novembre d’enregistrer deux faces, All’s Well et No Other One, de nouveau rejetées. Lors d’une tournée promotionnelle pour la MGM à New York, Judy est conviée dans les studios Decca de la 47e Avenue ouest le 12 juin 1936 pour enregistrer une reprise de Stompin’ at the Savoy (I, 3) avec Bob Crosby et son Orchestre, ainsi que Swing Mister Charlie. Cette fois-ci, les deux faces sortent comme son premier 78 tours. Judy Garland est dorénavant une artiste chez Decca. A la lumière succède la pénombre. Le jour suivant sa première interprétation de Zing! à la radio, le père adulé meurt. Il l’a entendue sur son lit d’hôpital. Son chagrin est immense et assombrit son triomphe. Elle a perdu Grand Rapids ; elle a perdu son père. Bien qu’elle aime chanter, la famille et l’affection se dissolvent. Elle gagne la célébrité d’un côté et se perd de l’autre. Le calice de la réussite restera toujours à moitié vide, où y surnageront l’amertume, la colère et l’auto-destruction. Ne sachant pas quoi faire d’une adolescente un peu ronde, la MGM, contre toute attente et après l’avoir utilisée dans deux courts-métrages, la prête à la 20th Century Fox pour son premier long métrage, Pigskin Parade (1936), une historiette à petit bud- get de football américain qui lui permet de jouer et chanter trois numéros percutants. La MGM se réveille et l’emploie pour son premier film maison, Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937), où Judy, dans l’un de ses premiers moments d’anthologie, chante (Dear Mr. Gable) You Made Me Love You à une photo de Clark Gable. L’intensité de l’interprétation frappe le public de l’époque et laisse pantois encore aujourd’hui. S’en suit une ribambelle de petits films, y compris le premier Andy Hardy avec Mickey Rooney, mais c’est bien sûr The Wizard of Oz (Le Magicien d’Oz, 1939) qui propulse Judy Garland au statut de légende. Bien que Garland fut le premier choix du studio pour le rôle de Dorothy, Shirley Temple, à l’époque une valeur du box-office bien plus importante que Garland, a été brièvement considérée pour le rôle. Mais elle est sous contrat à la Fox, qui refuse de la prêter. Le célèbre producteur et compositeur Arthur Freed sent que Garland peut jouer et chanter le rôle, et il lui est attribué. Son interprétation d’Over the Rainbow (I, 4) devient un autre moment marquant de sa carrière. En ce XXIe siècle, que peut-on encore dire de cet instant de grâce? Dans le film, Judy joue une jeune fille du Kansas comme tant d’autres à la recherche d’un ailleurs introuvable. Dans la vie, Judy est une jeune fille ordinaire du Minnesota transplantée par le génie de sa voix en terre hollywoodienne — un Hollywood qui ne saurait remplacer la vie qu’elle a quittée. Ce manque se retrouve dans sa voix, métamorphosant la chanson. Du saut d’un octave sur « somewhere » à l’intensité pathétique du « why, oh why can’t I ? », son chant est un cri primal, l’expression du rêve nécessaire où « ailleurs » est un endroit meilleur qu’il faut rechercher.

Pendant ses quinze années à la MGM, Judy Garland chante dans vingt-six comédies musicales, cinq courts-métrages, et joue dans un film purement dramatique, The Clock (L’Horloge, 1945). Elle travaille avec les meilleurs réalisateurs du studio, parmi lesquels Victor Fleming, George Cukor et King Vidor sur The Wizard of Oz; Busby Berkeley sur Babes in Arms (Place au rhythme, 1939), Strike Up the Band (En avant la musique, 1940), Babes on Broadway (Débuts à Broadway, 1941), For Me and My Gal (Pour moi et ma vie, 1942) et Girl Crazy (1943) ; Vincente Minnelli sur Meet Me in St. Louis (Le Chant du Missouri, 1944), The Clock, Ziegfeld Follies (1946), Till the Clouds Roll By (La Pluie qui chante, 1946) et The Pirate (Le Pirate, 1948) ; George Sidney sur Thousands Cheer (Parade aux étoiles, 1943) et The Harvey Girls (Les Demoiselles Harvey, 1946) ; Charles Walters sur Easter Parade (Parade de printemps, 1948) et Summer Stock (La Jolie fermière, 1950), son dernier film chez MGM. Elle travaille avec des acteurs de premier plan, y compris Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Mickey Rooney, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Hedy Lamarr, Lana Turner, Ann Miller et même Buster Keaton dans In the Good Old Summertime (1949). Les plus grands compositeurs et paroliers de l’époque écrivent pour la MGM, et Garland devient la première à y interpréter des titres devenus depuis des standards : Over the Rainbow (paroles de E. Y. Harburg/musique de Harold Arlen) ; How About You ? (Ralph Freed/Burton Lane) ; The Boy Next Door, Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas (I, 7) et The Trolley Song (Hugh Martin et Ralph Blane) ; On the Atchison, Topeka and the Sante Fe (Johnny Mercer/Harry Warren) (I, 8). Elle interprète de grands succès d’antan ainsi que des nouveautés expressément écrites pour elle : Singin’ in the Rain (Arthur Freed/Nacio Herb Brown) ; Who? (Oscar Hammerstein II, Otto Harbach/Jerome Kern) (I, 9) et Look for the Silver Lining (B.G. De Sylva/Jerome Kern) ; Better Luck Next Time (I, 12) et I Want to Go Back to Michigan (Down on the Farm) (Irving Berlin) ; Where or When, I Wish I Were in Love Again (I, 11) et Johnny One Note (Lorenz Hart/Richard Rodgers) ; You Can Do No Wrong (I, 10) et Love of My Life (Cole Porter) ; Get Happy (Ted Koehler/Harold Arlen) (I, 13). Les frères Gershwin furent une corne d’abondance pour Garland : But Not for Me (I, 6), I Got Rhythm, Embraceable You, Bidin’ My Time (Ira Gershwin/George Gershwin). Dans les années 1940, Judy Garland est l’une des plus grandes stars de la MGM, et la musique populaire américaine au plus fort de sa période classique. Le répertoire qu’elle se constitue est l’amalgame unique d’une artiste et de mélodies qui en restent pour toujours indissociables. Durant toutes ces années, la vie personnelle de Garland est loin d’être parfaite. De plus en plus dépendante de comprimés pour se maintenir éveillée et pour dormir, elle subit comme un fardeau les tournages non-stop et l’insistance du studio de surveiller sa ligne. Elle se marie deux fois pendant sa période MGM – avec le compositeur/chef d’orchestre David Rose, puis avec le metteur en scène Vincente Minnelli –, mais les deux se terminent en divorces. Elle s’éloigne aussi de sa mère qu’elle accuse de plus de maux qu’une mère puisse infliger. A la fin des années 1940, sa fragilité et sa nervosité deviennent évidentes à l’écran. Lui sont imputés des retards au tournage et une voix de qualité inégale. Des périodes dépressives, des troubles du sommeil et un mauvais régime alimentaire s’y ajoutent pour faire d’elle un grain de sable dans les rouages de la MGM, malgré un box-office qui ne se dément pas. Désormais incapable de fonctionner sur un plateau, Garland est libérée de son contrat le 29 septembre 1950. MGM a été sa maison pendant quinze ans. Elle tente de se suicider, puis de travailler à nouveau.

Débarrassée de contraintes journalières, Garland retourne à la radio et à la scène, comme au temps du vaudeville. Elle a aussi un nouvel homme dans sa vie – Sid Luft. Il produit Garland d’abord au Palladium à Londres à partir d’avril 1951, puis au Palace à New York en octobre. La réaction du public est époustouflante. On la connaît comme star du grand écran, mais à présent s’ajoute l’empathie provoquée par ses déboires personnels. Elle se souviendra à la fin de sa vie de sa première soirée au Palladium comme l’un des meilleurs moments de sa vie. Les Anglais l’adorent et la mettent à l’aise. La scène à New York est encore plus tumultueuse. L’explication, c’est que Garland se rend compte qu’elle est dans son élément sur scène, et non à l’écran. Face à un public qui l’aime, là, elle est elle-même, plaisantant et ôtant ses chaussures neuves peu confortables. A Londres, elle est même tombée sur scène après avoir trébuché. Qu’importe! Le public lui pardonne tout. Son spectacle est en grande partie composé de chansons qu’elle a créées dans ses films, mais en comporte aussi de nouvelles. Elle s’empare de Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody d’Al Jolson et la fait sienne. D’autres morceaux de bravoure s’insèrent dans le spectacle. Elle interprète A Couple of Swells d’Easter Parade déguisée en vagabond mal rasé, puis s’assoit au bord de la scène, en sueur, essoufflée, dans ses guenilles ridicules, et chante Over the Rainbow comme si sa vie en dépendait. Ceux qui y assistent se souviendront longtemps après de ce moment sublime. Elle reste à l’affiche du Palladium quatre semaines, du Palace – à deux spectacles par jour de surcroît – dix-neuf. Un record! Luft, un dur bagarreur qu’elle épouse en 1952, tente autant qu’il le peut de la préserver de ses démons. Il surveille ses médicaments et lui trouve des engagements. Elle travaille ; il gère. Il lui décroche un contrat avec la Warner Bros. pour une série de films, dont le premier est A Star is Born (Une étoile est née, 1954). Luft en est le producteur, Harold Arlen et Ira Gershwin composent la musique, Moss Hart écrit le scénario, George Cukor met en scène. Il faut que le premier film de Garland après la MGM soit un événement. Les talents réunis pour le projet sont tous des professionnels accomplis, dont la plupart ont travaillé avec elle depuis les années 1930. Depuis son départ de la MGM, la voix de Garland a quant à elle gagné en puissance du fait de ses prestations en concert. Le film n’est pas d’époque non plus, comme l’étaient Meet Me in St. Louis ou In the Good Old Summertime, mais solidement ancré dans la réalité hollywoodienne. L’alcoolisme et le suicide, hors-jeu dans les comédies musicales de la MGM, ne le sont pas ici. Impliquée financièrement dans la production, Garland se donne à fond. Le film, bien qu’ayant dépassé son budget et retardé en grande partie par la transition au CinemaScope, est le plus impatiemment attendu de 1954. La superproduction qui en résulte dépasse toutes les espérances. Y figure ce qui va devenir un autre classique de Garland, The Man That Got Away (I, 18). La direction de George Cukor n’est pas seulement celle d’un grand artisan hollywoodien, mais exhibe une profondeur insoupçonnée de sa part. Surtout, le jeu de Garland, plus intense que jamais, donne la chair de poule. Les critiques sont dithyrambiques, mais la Warner, davantage intéressée par les recettes que par les critiques, trouve le film trop long. Elle supprime plus de 30 minutes des 181 minutes originales, massacrant des séquences-clés, y compris musicales. Pire, bon nombre des parties coupées ne sont pas préservées. A Star is Born est la victime de l’affairisme cynique hollywoodien, qui est le sujet même du chef-d’œuvre amputé. Bien que sélectionné pour plusieurs Oscar, le film n’en remporte aucun, et signe pratiquement la fin de la carrière cinématographique de Judy Garland. Elle est devenue un outsider, un mauvais investissement. Il n’y aura plus de films à la Warner Bros.. En 1955 Garland signe avec Capitol Records, y enregistrant jusqu’en 1964. Elle poursuit ses tournées de concerts, parmi lesquels un autre engagement au Palace à New York en 1956, et est la vedette de ses premiers shows télévisés en 1955 et 1956, là où se termine la présente anthologie. Garland a continué de travailler jusqu’à sa mort. Parmi les moments de gloire à venir figurent le récital légendaire de 1961 à Carnegie Hall, dont l’album récolte cinq Grammy, parmi lesquels meilleure interprète féminine et album de l’année. «Judy at Carnegie Hall» reste quatre-vingt-quinze semaines au hit-parade, dont treize comme numéro un. C’est le plus grand spectacle de Judy Garland, inscrit au National Recording Registry de la Bibliothèque du Congrès en 2003. Pour beaucoup, c’est le plus grand enregistrement public de variétés du XXe siècle. Elle retourne à l’écran avec Pepe (1960), Judgment at Nuremberg (Jugement à Nuremberg, 1961), Gay Purr-ee (1962), A Child is Waiting (Un enfant attend, 1963) and I Could Go on Singing (L’Ombre du passé, 1963). Saisie presqu’au sommet de sa voix dans « The Judy Garland Show », une série de vingt-six émissions télévisées qu’elle entreprend entre 1963 et 1964, Garland par la suite ne peut plus prodiguer la magie de jadis. La flamme s’est éteinte, la voix est abîmée et la dépendence aux médicaments hors contrôle. Sans agents ou maris pour gérer ses finances, elle se voit forcée en 1967 de vendre sa maison californienne. En 1968, elle se retrouve parfois à la rue. Elle meurt le 22 juin 1969 d’une overdose accidentelle de somnifères dans une maison louée à Londres. Elle avait proclamé « rien ne vaut chez soi » (« there’s no place like home ») dans The Wizard of Oz, mais Judy Garland n’a jamais trouvé de chez-soi – aucun qui puisse rivaliser avec celui de Grand Rapids si lointain à présent. Depuis sa mort, Judy Garland a inspiré des pièces de théâtre, des chansons, des poèmes, des romans, des bandes dessinées, des tableaux, des documentaires, des rétrospectives muséographiques et des études académiques. On l’a jouée à Broadway et au cinéma. Des hommages lui ont été consacrés à Paris et San Francisco. Elle a été « remasterisée », « remixée » et « échantillonnée ». Des licences ont été achetées pour des publicités télévisées. Over the Rainbow a été élue « chanson du siècle » et cinq de ses enregistrements sont entrés au Grammy Hall of Fame. Depuis 1969, un bon nombre de concerts et enregistrements de studio jamais sortis ont refait surface – y compris l’enregistrement-test de Bill chez Decca en 1935, déniché en 2006, ainsi que son tout premier concert à Philadelphie en 1943, retrouvé en 2007. Beaucoup sont parus. Il y a eu plus de trente biographies ou mémoires à son sujet. Rien qu’en France, trois biographies furent publiées, bien que jamais traduites. En Hongrie, une hagiographie non-traduite a vu le jour. Au Québec, elle fut la trame d’une nouvelle. Certains de ses films furent montés à Broadway. On l’a honorée par un hommage à Carnegie Hall et même par une reprise intégrale de son célèbre concert là-bas. Il y a un timbre et une rose Judy Garland. La maison du Minnesota où elle a vu le jour est devenue un musée. Les sites Internet qui lui sont consacrés sont parmi les mieux conçus de la Toile. Ses films sont sortis en VHS, Laser Disc et DVD. Ses enregistrements sont presque tous sur CD. La société marchande l’a aussi commercialisée en poupée et boîte à musique. On peut la télécharger comme sonnerie sur son téléphone portable. J’ai vu Judy Garland en concert d’abord en 1965, puis en 1967 lors de sa première au Palace à New York, où adolescent fauché, je ne pouvais me permettre qu’une place bon marché au deuxième balcon. Quelque peu désarçonné par la frénésie qu’elle inspirait, j’ai tout pris en pleine figure. Après l’ouverture, un tonnerre d’applaudissements éclata, mais pas de Judy Garland en vue. Dans un habit à sequins dorés, elle est entrée par le fond de la salle et non côté jardin comme d’habitude. Une éternité s’écoula avant qu’elle n’atteigne la scène à travers les fauteuils d’orchestre et les bras tendus des spectateurs. Perché sur mon balcon, je ne voyais rien de ce qui se passait. Enfin, elle fut là. L’amour du public avait une ferveur comme je n’en avais jamais vue. Elle chanta, et je me souviens de What Now, My Love? (Et maintenant de Gilbert Bécaud). Le dernier mot de la chanson – « good-bye » – était haut placé sur une note que la voix de Garland ne pouvait désormais atteindre que les bons jours. L’ambiance dans la salle était électrique, physiquement palpable. Le silence avant « good-bye » était assourdissant. Enfin, elle atteignit la note et la salle devint hystérique. J’ai compris alors que l’on ne pourrait jamais prétendre tout savoir de cette créature multi-dimensionelle, d’ici et d’ailleurs. J’ai compris l’importance de Judy Garland.

Lawrence SCHULMAN

MUSICALEMENT PARLANT

Le CD I contient des enregistrements studio de Judy Garland réalisés entre 1929 et 1956. Les chapitres 1 et 2, Blue Butterfly et Hang on to a Rainbow, des films A Holiday in Storyland et The Wedding of Jack and Jill respectivement, sont les plus anciens éléments discographiques préservés de la chanteuse, faits à l’âge de sept ans et demi. Enregistrés en direct sur disque par Vitaphone pendant le tournage des deux courts-métrages sonores fin 1929, ces disques sont des exemples d’une des premières techniques sonores du cinéma en vigueur de 1926 à 1930. Joués de l’intérieur vers l’extérieur à 33⅓ tours/minute pour durer 11 minutes, temps d’une bobine de court-métrage, ces disques exigent du projectionniste, pour synchroniser le son et l’image, de poser le disque sur une platine et aligner la marque de départ, indiquée par une flèche sur l’étiquette, avec la marque de départ du film. Les prestations de la jeune Frances ne durent qu’une partie des disques. Le troisième court métrage Vitaphone de Garland, Bubbles, (VITAPHONE 3890, filmé au mois de décembre 1929, sorti en janvier 1930), où elle apparaît une fois encore comme membre des Vitaphone Kiddies, contient les Gumm Sisters interprétant In the Land of Let’s Pretend (Grant Clark/Hary Akst). Les disques Vitaphone des trois courts-métrages ont tous survécu. En revanche, aucune pellicule des films n’existe à ce jour, si ce n’est une copie noir-et-blanc en nitrate de Bubbles, photographié à l’origine en Technicolor bichromatique, découverte dans la Bibliothèque de Congrès au début des années 1990. Les trois courts-métrages Vitaphone de Garland ont été réalisés par Roy Mack. Stompin’ at the Savoy, chapitre 3, fut le premier 78 tours sorti chez Decca de Garland. Elle a 14 ans lorsqu’elle l’enregistre, bien que l’étiquette du disque lui attribue incorrectement 13 ans. Bob Crosby et son Orchestre n’y sont pas mentionnés, puisque le manager de l’orchestre, Gil Rodin, a dit à Decca « nous ne voulons pas que notre nom figure sur le disque à côte d’une fille inconnue ». Comme la MGM n’a pas eu de division discographique commerciale avant 1946, Garland a sorti la musique de ses films sur disques Decca jusqu’à cette année-là. Les versions Decca, enregistrées dans les studios de Decca, sont toujours différentes de celles de la MGM, enregistrées à la MGM et utilisées pour la piste optique du film. Heureusement, Decca lui a permis d’enregistrer des chansons ne provenant pas de ses films. Elle commença à sortir des disques MGM de ses films MGM en 1946, l’année du démarrage de MGM Records, bien que sa dernière séance chez Decca date de 1947. Over the Rainbow, chapitre 4, écrite pour The Wizard of Oz, est la version MGM. Elle est un montage de la prise 5 (début du premier refrain : « Somewhere over the rainbow way up high, » /) et la prise 6 (/ « There’s a land… »). Elle enregistra la chanson chez Decca aussi, mais cette interprétation-là, bien qu’au sommet des ventes de 1939, est de qualité artistique bien inférieure. L’Over the Rainbow de la MGM n’est sorti commercialement qu’en 1956, lorsque MGM Records sortit un 33 tours d’extraits musicaux et dramatiques du film, d’où provient ce morceau. Le chapitre 5, I’m Just Wild About Harry, enregistrée en 1939 chez Decca, est sortie au Royaume-Uni en 1943 chez Brunswick, une filiale, mais jamais aux Etats-Unis. Garland l’interpréta également dans le film Babes in Arms. Les chapitres 6 – 8 sont des versions Decca de chansons que Garland chanta dans des films MGM. Le chapitre 9, Who? est sortie en 1946 comme une face du tout premier album MGM de bandes originales, Till the Clouds Roll By, constitué de quatre 78 tours. You Can Do No Wrong, chapitre 10, sortie en 1948, provient de l’album original de trois 78 tours du film The Pirate, qui est l’unique fois où Cole Porter écrivit pour un film de Judy Garland. I Wish I Were in Love Again, chapitre 11, fut enregistrée lors de l’ultime séance de Garland chez Decca. L’accompagnement à deux pianos de chez Decca est très éloigné de l’orchestration à la MGM dans Words and Music (avec Mickey Rooney), également disponible à l’époque en 78 tours (MGM Records, M-G-M 37, quatre disques, 30172-B). Better Luck Next Time, chapitre 12, extraite de la bande originale en quatre 78 tours d’Easter Parade, est sortie en 1949. Le film marque la seule fois où Irving Berlin a écrit pour un film de Garland. La partition est un mélange d’anciennes et nouvelles mélodies de Berlin. Le chapitre 13, Get Happy, du film Summer Stock, est le dernier enregistrement de Garland à la MGM. Lorsque le studio a jugé qu'il fallait un numéro musical supplémentaire vers la fin du film, c’est elle qui a choisi cette chanson, qui fut le premier succès de Harold Arlen et Ted Koehler en 1930. Elle l’a été enregistrée et filmée un mois après la fin du tournage principal. Les chapitres 14–17 sont des remasterisations effectuées par l’ingénieur du son australien Robert Parker (1936-2004) en 2002 pour l’auteur de cette anthologie. Dans une lettre à mon intention concernant ces morceaux, il affirma : « Ce sont des mixages en son surround faits à partir de 78 tours Columbia en vinyl pour stations de radio, datant d’environ 1953, que j’ai récemment acquis en parfaite condition. A écouter de préférence avec décodage PRO LOGIC – mais compatibles pour la reproduction stéréo ou mono ». Aucune séance d’enregistrement en studio de Garland n’est jamais sortie en surround. Après avoir quitté la MGM en 1950, Garland n’a pas eu de maison de disques jusqu’à ce qu’elle signe un contrat avec Mitch Miller de chez Columbia en 1953 pour ces quatre faces, toutes enregistrées le 3 avril 1953 en trois heures et trente prises. Columbia a aussi sorti A Star is Born sous différents formats. Le chapitre 18, The Man That Got Away, du film A Star is Born, est un autre classique de Garland. Après quatre prises, Garland a préféré cette version dramatique à une version plus détendue préférée par son coach vocal Hugh Martin, qui quitta le film en désaccord. Judy at the Palace, chapitre 19, provient du premier 33 tours de Garland chez Capitol en 1955. Chantée par elle pour la première fois en 1951 lors de son récital au Palace à New York, elle commémore les artistes qui se produisirent autrefois au Palace, un théâtre mythique du temps où régnait le vaudeville. Elle comprend l’adaptation anglaise de Mon homme, rendue célèbre en Amérique par Fanny Brice. Enfin, le chapitre 20, Memories of You, provient de son second 33 tours Capitol en 1956.

Le CD II contient des prestations provenant d’émissions radiophoniques enregistrées en direct entre 1935 et 1951, dont toutes sauf une (chapitre 2) sont inédites sur CD. Douze des sélections (chapitres 1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16 [The Man I Love]), 17, 18, 20) ne furent jamais commercialement enregistrées par Garland. La première apparition connue de Judy Garland à la radio a eu lieu en 1928, mais c’est seulement après qu’elle eut signé avec la MGM en 1935 que l’on commence à l’entendre régulièrement sur les ondes. La MGM se servait de la radio pour promouvoir ses films, et Garland s’est pliée à ce jeu dans des centaines d’émissions dans les années 1930, 1940 et jusqu’au début des années 1950. Heureusement, elle a aussi interprété des chansons ne provenant pas de ses films. Les émissions radiophoniques de Garland, obstinément recherchées et archivées par John Walther en Allemagne, ainsi que Kim Lundgreen au Danemark, furent enregistrées sur des disques de transcription. Beaucoup ont survécu, mais beaucoup n’existent aujourd’hui que sur bande ou CDR. Garland cessa de chanter en direct à la radio en 1953, quand la télévision devenait le média dominant aux Etats-Unis. Que tant de prestations radiophoniques garlandiennes ne soient jamais sorties ne laisse pas d’étonner. Parmi les points forts de la présente collection figure Broadway Rhythm, chapitre 1, première apparition radiophonique conservée de Garland. Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart, chapitre 2, est la deuxième apparition radiophonique conservée de Garland. Elle chantera Smiles, chapitre 4, dans le film For Me and My Gal. Dans le chapitre 6, On the Bumpy Road to Love, on entend Robert Young, Fanny Brice, Frank Morgan, Joan Crawford et un chœur. Elle l’interpréta dans le film Listen, Darling (1938). Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, chapitre 7, est un extrait de spot radio. Elle l’interpréta dans le film Everybody Sing (1938). Le chapitre 10, Love’s New Sweet Song, est la première fois qu’un air écrit par Garland (paroles) et David Rose (musique) est sorti. Garland interpréta Minnie from Trinidad, chapitre 13, dans le film Ziegfeld Girl (1941). Johnny Mercer s’inspira de son affaire avec Garland au début des années 1940 pour écrire les paroles de That Old Black Magic, chapitre 14. L’orchestre y est dirigé par Andre Kostelanetz. L’Over the Rainbow du chapitre 15 est interprétée avec un chœur. Andre Kostelanetz, le chef d’orchestre, fut le chef d’orchestre lors du tout premier récital de Garland au Robin Hood Dell à Philadelphie le 1er juillet 1943, dont un double-33 tours privé fabriqué par Studio Recording Incorporated a refait surface en 2007. Garland interpréta Embraceable You, chapitre 16, dans le film Girl Crazy, d’après lequel est sorti le coffret Decca 362, mais n’a jamais interprété The Man I Love ni au cinéma ni pour une maison de disques. Le chapitre 18, Someone to Watch Over Me, fut enregistrée pour un disque privé, mais jamais diffusée. You and I, chapitre 20, est une chanson différente de celle homonyme dans Meet Me in St. Louis.

Lawrence SCHULMAN

Traduit de l’anglais par Alain FALASSE

© 2008 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini SAS

Auteur de l’anthologie : Lawrence Schulman - Traduit de l’anglais par Alain Falasse. / Transferts par Jon M. Samuels, New York - Restauration par Art & Son Studio, Paris. / Recherche discographique par Lawrence Schulman - Recherche radiophonique par John Walther. / Archives discographiques de Fred McFadden et Lawrence Schulman - Archives radiophoniques de John Walther, Kim Lundgreen, Laura Pilot et Lawrence Schulman - Pochettes d’albums et partitions musicales : collection Lawrence Schulman. / Merci à Christian Matzanke, Jerry Waters, Gary Galo (Association for Recorded Sound Collections), Nancy Colter, Rich Tozier (Maine Public Broadcasting Network), Emy Leeser, John Fricke, Scott Schechter, Max O. Preeo et Henriette Falasse.

À la mémoire d’Estelle Schiller et de Jim Grant.

english notes

The more you know Judy Garland (1922-1969) the more you know you know nothing. There are no experts. She is a majestic mystery. She was everywhere and nowhere during her all-too-short existence. Undefined and indefinable, she would flutter from film to film, from recording session to recording session, from concert to concert all over the planet. People would applaud and love her until their hands, hearts and patience gave out. She “entertained” us, but drug-laden days and sleepless nights left her a lonely figure, phoning friends at all hours, playing pool in Times Square in the middle of the night. She wasn’t just lonely – she was alone. Husbands, friends and fans could not save this vagabond soul who thrived on chaos and thumbed her nose at it. She withered from the weight of being “the ugly duckling”, “the little hunchback” studio heads viewed her as in youth; from the responsibility of being a child prodigy when nobody had asked her her permission to be in the business in the first place; from the bereavement over her father’s sudden death from spinal meningitis when she was 13, “the most terrible thing that ever happened” to her, she recalled. She sang in later years that she was “born to wander”, but her upper Midwest pronunciation of “wander” sounded like “wonder.” Wandering and wondering were one and the same, and her road would be rough, short-lived and often squalid. Despite all, there was that voice: big, warm, and natural. A contralto of limited range, she could hit a high C or go down to a low E flat when needed. Her vibrato varied according to her physical and emotional state. She could not improvise. Her breathing went from robust, when she didn’t need to place a breath where other singers might have to, to passable, when she was thin and her nerves shot. She didn’t always sing the vowel, but would emphasize the consonant at the end of the word. She certainly could swing in her early career, as the era required her to, but it wasn’t natural. The raw emotion she projected leant itself more to pop than jazz. Still, her very rare incursions into a more jazzy style throughout her career leave the listener wondering what might have been had she started out, like Peggy Lee or Frank Sinatra, as a big band singer. The voice was big, almost operatic, even in her earliest extant performances, and it got bigger with age. Making the rafters ring at Metro or the Met was not a problem. Going from speaking to singing was seamless, and this natural aplomb contributed to her cinematic natural. Above all, she had a real sincerity that came through. The listener believed and hung on to every note she sang. Not just every word had meaning, but every syllable, every silence, every breath kept you on the edge of your seat. She was riveting, and spoke to you and you alone. To some, entertainment on this level was no longer entertainment, but art.

That voice lives on today, but Judy Garland lasted a short forty-seven years. Born on June 10, 1922 in Grand Rapids, Minnesota to Ethel and Frank Gumm, Frances Ethel Gumm, as she was named, was the youngest of three daughters. The Gumm sisters – Mary Jane (aka Suzy), the eldest, Virginia (aka Jimmy), and Frances “Baby” Gumm – became The Gumm Sisters in those days of vaudeville when performing at their father’s New Grand Theater. Ethel, the typical stage mother, played piano. In those days of “kiddie” acts Ethel and Frank were a show business family, encouraging the girls onto the vaudeville route early on. Ethel saw the potential, artistic and financial, of the sisters, especially Frances’, whose talent set her apart even then. Frank was the proud father. “Baby” Gumm first performed solo at her father’s theater in 1925, when she sang Jingle Bells to an enthralled audience. The thrill and warm glow of that moment stayed with her the rest of her life. In fact, all of Grand Rapids stayed with her. She would remember her comfortable life in a small Norman Rockwell town with affection. Photos survive of her sitting and playing on the lawn in front of their small white house, the perfect home. These were happy moments, pristine memories that were taken away as Ethel took the act on the road. Ethel surely meant to make ends meet, but she also substituted her own interests over those of the girls. There had been rumors about Frank’s infidelity, homosexual at that, and the girls must have been witness to disputes. Ethel sought an escape. The road was a way out. Young Frances loved to perform but hated leaving Grand Rapids and her doting father. This love of the limelight and hate of what it stole ate at her the rest of her life. In late 1926 the Gumms moved to Lancaster, California, where Frank bought and managed the Lancaster Theater. The dream was over. The Gumm Sisters were closer to Hollywood. Ethel could get the girls engagements on the vaudeville circuit, and Frank could start anew. Lancaster – a dusty town about a three-hour drive from Los Angeles – wasn’t Grand Rapids though. For young Frances, youth was over. The Sisters performed fairly regularly on the West coast in the late 1920s, even on local radio. In this transition period between silent films and talkies, musical acts were in demand, and The Gumm Sisters were hired by Mayfair Pictures to sing That’s the Good Old Sunny South in a two-reeler, The Big Revue, filmed in June 1929 at the Tec-Art Studios in Hollywood. Shortly thereafter, they started performing with The Meglin Kiddies both on stage and in film, and did three short subjects in November and December 1929 for First National-Vitaphone Pictures - A Holiday in Storyland, The Wedding of Jack and Jill, and Bubbles -, wherein Frances performed her first screen solos, Blue Butterfly (I, 1) and Hang on to a Rainbow (I, 2).

But their first real break came in 1934. In July the girls got booked at the Chicago World’s Fair, then at the Oriental Theatre in August, where headliner George Jessel, exasperated at seeing the act variably billed as the Gum Sisters, the Gun Sisters and the Glumm Sisters, first introduced them as The Garland Sisters, after New York drama critic Robert Garland. By March 1935, the trio, with Ethel on piano, cut three test records for Decca – Moonglow, Bill wherein Frances soloed, and a medley of On the Good Ship Lollipop/The Object of My Affection/Dinah – but all were rejected. The turning point of Judy Garland’s life occurred when the Gumm/Garland Sisters appeared at Lake Tahoe’s Cal-Neva Lodge that summer. By then Frances had chosen to be called Judy, after the contemporary Hoagy Carmichael tune of the same name. Agent Al Rosen and songwriter Harry Akst caught the trio’s closing night, and after the show asked Judy to sing Dinah, written by Akst, who accompanied her. Both were floored, and Rosen started making the rounds of Hollywood studios. At the in-between age of 13, Judy was a hard sell. In the end, Rosen got her an audition at MGM on September 13, and in front of Louis B. Meyer she belted Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart and Eili, Eili. Judy Garland signed with MGM on September 16, 1935. In two historic Shell Chateau radio appearances at KFI Studios in Los Angeles following her signing, Judy slammed Broadway Rhythm (II, 1) and Zing! (II, 2). Decca once again took note, and had her cut two sides – All’s Well and No Other One in November. Both were once again rejected. On an MGM promo tour in New York, Judy was invited into Decca’s West 57th Street studio on June 12, 1936 to record a cover of Stompin’ at the Savoy (I, 3) with Bob Crosby and his Orchestra, along with Swing Mister Charlie. This time, the two sides were released as Judy’s first 78 rpm single. Judy Garland was now a Decca recording artist too. Night follows day. The day after she sang Zing! for the first time on radio, her beloved father Frank died. He was listening as he lay in hospital. Her loss was immeasurable. Success would always be tainted. She had lost her Grand Rapids; she had lost her father. She did love to sing, but a sense of home and real love were slipping away. She was gaining fame, but losing herself. The cup of success would always be half empty and the source of bitterness, anger and self-destruction. Strangely, after assigning her two short subjects, MGM, not knowing what to do with a plumpish young adolescent, loaned her to 20th Century Fox for her first feature, Pigskin Parade (1936), a low-budget football yarn that allowed Judy to act and sing three knock-out numbers. MGM took note and placed her in her first feature there, Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937), in which Judy, in one of her first signature screen moments, sang (Dear Mr. Gable) You Made Me Love You to a photo of Clark Gable. The intensity of her interpretation left an indelible mark on the public. There followed a string of small films, including the first Andy Hardy she did with Mickey Rooney, but it is, of course, The Wizard of Oz (1939) that turned Judy Garland into a legend. Although Garland was the studio’s first choice for the role of Dorothy, Shirley Temple, a bigger box-office draw than Garland at the time, was briefly considered for the part. But Temple was at Fox, which refused to loan her. Famed MGM producer and songwriter Arthur Freed knew Garland had the voice and acting ability for the part, and she got it. Judy’s interpretation of Over the Rainbow (I, 4) was another founding cornerstone of her career. Today, in the 21st century, what more can be said of that film moment? Judy in the film plays a plain girl from Kansas longing for an elsewhere she cannot find. Judy in life was a plain girl from Minnesota plummeted by the genius of her voice into a Hollywoodland she could never find to be equal to the home she had left. Her loss is in her voice, making the song, from the octave leap on the opening word “somewhere” to the pathetic intensity of the closing tag “why oh why can’t I?” an elemental cry, the necessary dream that elsewhere must be good, and sought.

During her fifteen-year tenure at MGM, Judy Garland sang in twenty-six musicals and five short subjects or trailers, and acted in one non-singing film, The Clock (1945). She worked with some of the best directors on the lot, including Victor Fleming, George Cukor and King Vidor on The Wizard of Oz; Busby Berkeley on Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), Babes on Broadway (1941), For Me and My Gal (1942) and Girl Crazy (1943); Vincente Minnelli on Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), The Clock, Ziegfeld Follies (1946), Till the Clouds Roll By (1946), and The Pirate (1948); George Sidney on Thousands Cheer (1943) and The Harvey Girls (1946), Charles Walters on Easter Parade (1948) and Summer Stock (1950), her last MGM picture. She got to work with some of the studio’s top leading men and women, including Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Mickey Rooney, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Hedy Lamarr, Lana Turner, Ann Miller, and even Buster Keaton on In the Good Old Summertime (1949). The greatest composers and lyricists of the era wrote original music for MGM films in which Garland was the first to perform tunes that in time would become standards: Over the Rainbow (words by E. Y. Harburg/music by Harold Arlen); How About You? (Ralph Freed/Burton Lane); The Boy Next Door, Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas (I, 7) and The Trolley Song (Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane); On the Atchison, Topeka and the Sante Fe (Johnny Mercer/Harry Warren) (I, 8). Songwriters saw early hits revived and composed new material for Garland to sing: Singin’ in the Rain (Arthur Freed/Nacio Herb Brown); Who? (Otto Harbach, Oscar Hammerstein II/Jerome Kern) (I, 9) and Look for the Silver Lining (B.G. De Sylva/Jerome Kern); Better Luck Next Time (I, 12) and I Want to Go Back to Michigan (Down on the Farm) (Irving Berlin); Where or When, I Wish I Were in Love Again (I, 11) and Johnny One Note (Lorenz Hart/Richard Rodgers); You Can Do No Wrong (I, 10) and Love of My Life (Cole Porter); Get Happy (Ted Koehler/Harold Arlen) (I, 13). The Gershwin brothers were a reservoir for Garland: But Not for Me (I, 6), I Got Rhythm, Embraceable You, Bidin’ My Time (Ira Gershwin/George Gershwin). In the 1940s Judy Garland was one of MGM’s biggest stars, and American popular music was in its classic period. The repertoire she amassed was a unique amalgam of artist and great tunes that would forever be associated with her. Garland’s personal life in these years was not so stellar. Increasingly addicted to pills to get her up and pills to get her to sleep, she found the stress of working constantly and the studio’s insistence on keeping her weight down a burden. She married twice while at MGM – to composer/conductor David Rose, then to director Vincente Minnelli –, but both ended in divorce. She also became estranged from her mother, whom she blamed for more sins than any mother can be responsible for. By the late 1940s Garland’s frailty and anxiety were all too apparent on screen. Delays in shooting, fluctuating vocal quality, depressive episodes, and major sleep and nutritional disorders accumulated to make her a cog in the MGM wheel despite her continuing good box-office. No longer able to be counted on to make it to the set, Garland was released from her contract on September 29, 1950. MGM had been home to her for fifteen years.

She tried suicide, then tried to get back to work.

Liberated from the constraints of a daily grind, Judy went back to radio and performing live on stage, just as she had done in her vaudeville days. She also had a new man – Sid Luft. He “produced” Garland first at the London Palladium starting in April 1951, then at The Palace in New York in October. The public’s reaction to Judy’s act was phenomenal. They knew her as a screen star, but now there was added empathy due to all her personal woes. At the end of her life she remembered her first Palladium appearance as one of the high points of her life. The British loved her and made her feel at home. The scene in New York was even more pandemoniac. What had happened was that Garland was finding that her natural place was on stage, not on screen. It was only in the presence of a loving audience that she could be herself, fling her shoes off, joke. In London she had even tripped on stage and fallen, but the crowd loved her anyway. Her act was pretty much a compendium of the film songs she had created, but she did new numbers too. She took Al Jolson’s Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody and made it her own. Other powerful elements were worked into the act. She performed A Couple of Swells from Easter Parade in the tramp outfit and with black-stubble make-up, then sat on the edge of the stage, sweating, out of breath, down-and-out in her ridiculous outfit, and sang Over the Rainbow as if her life depended on it. Decades later audience members remembered the searing power of that moment. The Palladium engagement lasted four weeks; the one at The Palace – at two shows a day at that – a record nineteen! Luft, a rough-and-tumble guy whom she married in 1952, tried to protect her as much as he could from her demons. He controlled her medication and got her bookings. She worked; he managed. He got her a deal with Warner Bros. for a series of films, the first of which was A Star is Born (1954). Luft produced, Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin wrote the music, Moss Hart did the screenplay, George Cukor directed. Garland’s first film since leaving MGM had to be an event, and the talent assembled for the project were all old pros, many of whom had worked with Judy since the 1930s. Garland’s voice was now far more powerful as a result of the concert work she had done since leaving Metro. This would not be a period picture either, as were Meet Me in St. Louis or In the Good Old Summertime, but one solidly set in the real world of Hollywood. Alcohol and suicide were not story options in MGM musicals. Garland gave it her all, as she owned an interest in the production. The production, although over budget and overdue mainly from delays involving the transition to CinemaScope, was the most highly anticipated film of 1954. The resulting three-hour blockbuster went beyond all expectations. The score included what would become another Garland classic, The Man That Got Away (I, 18). George Cukor’s direction was not just that of a great Hollywood craftsman, but showed a depth many had never seen before. Above all, Garland’s performance was of goose bump intensity – far more powerful than anything she had ever done. Critics were ecstatic, but the film was considered too long by Warners, which could make more money by more showings a day. They cut more than 30 minutes from the original 181 minute print, massacring key sequences, including musical ones. Worse, hardly any of the deleted footage was preserved. A Star is Born became an amputated victim of Hollywood business-as-usual, the very subject of the now-dismembered masterpiece. Though nominated for numerous Oscars, the film won none, and was pretty much the end of Judy Garland’s movie career. She was now a Hollywood outsider, a non money-maker. There would be no more films at Warners. Garland signed with Capitol Records in 1955, recording for them until 1964. She continued her concert tours, including a second engagement at The Palace in New York in 1956, and starred in her first television specials in 1955 and 1956, where this anthology ends.

Garland continued working until the day she died. Future highlights included the legendary 1961 Carnegie Hall appearances, the album of which garnered five Grammys, including best female solo vocal performance and album of the year. “Judy at Carnegie Hall” charted at #1 for thirteen weeks and remained on the charts for ninety-five. It is Judy’s greatest performance, added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress in 2003. To many it is the greatest live pop recording of the 20th century. She returned to the screen in Pepe (1960), Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), Gay Purr-ee (1962), A Child is Waiting (1963) and I Could Go on Singing (1963). Captured near her vocal peak for “The Judy Garland Show”, a series of twenty-six television shows she did between 1963 and 1964, Garland never again captured the magic of yesteryear. The sparkle was gone, the voice shot, the drug addiction out of control. Never having managers or husbands capable of getting a handle on her finances, she was forced in 1967 to sell her California home. By 1968 she was at times on the street. She died in her rented London house on June 22, 1969 of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills. She had proclaimed “there’s no place like home” in The Wizard of Oz, but Judy Garland never found one – never one as good as the one she had left in Grand Rapids life-years earlier.

Since her death, Judy Garland has been the inspiration for plays, songs, poems, novels, comic books, paintings, documentaries, museum retrospectives, and academic studies. She has been played on Broadway and film. Cabaret tributes have honored her in Paris and San Francisco. She has been remastered, remixed and “sampled” by rock groups. She has been licensed for TV ads. Over the Rainbow has been elected “song of the century” and five of her recordings have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Since 1969 a good number of studio tracks and unreleased concerts have surfaced – including the 1935 Decca test recording of Bill, unearthed in 2006, as well as her very first concert in Philadelphia in 1943, found in 2007. Many have been issued. There have been over thirty biographies or memoirs written about her in English. Three biographies on Garland have been published in French, though never translated. In Hungarian one untranslated one is in print. She was the basis for a novella in Québécois. Some of her movies have been revived on Broadway. She has been honored by a memorial concert tribute at Carnegie Hall and even a start-to-finish reprisal of her 1961 show there. There is a Judy Garland stamp and a Judy Garland rose. The Minnesota home where she was born is now a museum. Websites dedicated to her are among the best on the Net. Her movies have been released on VHS, Laser Disc and DVD. Her recordings are almost all on CD. Our capitalistic world has made dolls and music boxes out of her. She can be your ringtone. I saw Judy Garland perform in 1965 and 1967. The latter was on her opening night at The Palace in New York. A teenager then with little money, I could afford an inexpensive seat in the last balcony. Somewhat taken aback by the frenzy she inspired, I took it all in. After her overture, applause thundered, but there was no Judy Garland. Dressed in a gold-sequined suit, she had entered from the theater lobby and not from stage left as usual. It seemed like hours before she made it to the stage through the orchestra seats and loving arms reached out to her. Up in the balcony, I couldn’t see the goings on. Finally, she was there. The love being expressed by the audience was of a fervor I had never witnessed. She sang, and I remember her doing What Now, My Love?. The last word of the song – “good-bye” – was a high note Garland’s voice could only make on good days now. The electricity in the house was thick enough to cut, physically palpable. The silence before that “good-bye” was deafening. Finally, she made the note and the house went crazy. I knew then I could never really know everything about such an unfathomable creature. I only knew of the importance of Judy Garland.

Lawrence SCHULMAN

MUSICALLY SPEAKING

CD I contains studio recordings Judy Garland made between 1929 and 1956. Chapters 1 and 2, Blue Butterfly and Hang on to a Rainbow, from A Holiday in Storyland and The Wedding of Jack and Jill respectively, are the earliest preserved discographic elements by the singer, made at the age of 7 ½. Recorded by Vitaphone live onto disc while filming two sound short subjects in late 1929, these discs are examples of an early sound films technology that lasted from 1926 to 1930. Played from the inside to the outside at 33⅓ rpm so as to last eleven minutes, the running time for a one-reel short subject, these discs required the projectionist, in order to synchronize sound and image, to place the disc on a turntable and align the start mark of the disc, consisting of an arrow on the label, with the start mark on the film. The young Frances’ performance is just part of the contents of the respective discs for each short. Judy’s third 1-reel Technicolor Vitaphone short, Bubbles (VITAPHONE 3898, filmed sometime in December 1929, released in January 1930), where she appears once again as part of The Vitaphone Kiddies, contains The Gumm Sisters performing In the Land of Let’s Pretend (Grant Clarke/Harry Akst). Vitaphone discs survive of all three Garland Vitaphone shorts, although to date no film elements survive except a black and white nitrate print of Bubbles, originally photographed in two-color Technicolor, discovered at the Library of Congress in the early 1990s. All three Garland Vitaphones were directed by Roy Mack. Stompin’ at the Savoy, Chapter 3, was Garland’s first 78 released by Decca. She was 14 when she recorded the track, although the record label incorrectly gives her age as 13. Bob Crosby and his Orchestra are not mentioned on the label, as the band’s manager, Gil Rodin, told Decca “we didn’t want to use our name on the same record label with this unknown girl.” Since MGM had no commercial recording division until 1946, Garland released singles on Decca of music from her films up to 1946. Her Decca records are never the same as her MGM sound track recordings, which were used for the films’ optical tracks. Fortunately, Decca allowed her to record some non-film-derived songs too. She started releasing MGM singles from her MGM movies in 1946, when MGM Records was formed, although her last Decca session occurred in 1947. Over the Rainbow, Chapter 4, is the film version of the song, which is an edit of take 5 (beginning of first chorus: “Somewhere over the rainbow way up high,”/) and take 6 (/”There’s a land…”). She recorded the song for Decca too, but that interpretation, although 1939’s top-selling record, is artistically far inferior. The MGM Rainbow was not commercially released until 1956, when MGM Records released an LP of musical and dramatic selections from the sound track for The Wizard of Oz, from which this track is taken. Chapter 5, I’m Just Wild About Harry, was recorded in 1939 for Decca and released in 1943 in the U.K on Brunswick, a Decca subsidiary. It was never issued in the U.S.. Garland also sang the tune in the film Babes in Arms. Chapters 6–8 are Decca releases of songs Garland did in MGM films. Chapter 9, Who? was released in 1946 as part of MGM’s first sound track album for Till the Clouds Roll By, which consisted of four 78s. You Can Do No Wrong, Chapter 10, released in 1948, comes from the three-78 sound track album of the film The Pirate, which marked the only time Cole Porter wrote for a Judy Garland film. I Wish I Were in Love Again, Chapter 11, was recorded at Garland’s very last Decca recording session. The two-piano accompaniment at Decca is a far cry from the MGM orchestration in the Words and Music sound track album (with Mickey Rooney), it too available at the time on 78 (MGM Records, M-G-M 37, four discs, 30172-B). Better Luck Next Time, Chapter 12, from the four-78 sound track album of the film Easter Parade, was released in 1949. The film marked the only time Irving Berlin wrote for a Garland film. The score was a mix of old and new Berlin tunes. Chapter 13, Get Happy, was the last recording Garland ever did at MGM. She chose the tune, which had been Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler’s first big hit in 1930, after the studio found that an additional number was needed near the end of the picture Summer Stock. It was recorded and filmed a month after principal filming had wrapped. Chapters 14–17 are remasters done by Australian sound engineer Robert Parker (1936-2004) in 2002 for the author of this anthology. In a letter to me concerning these sides, he stated: “Some surround mixes I’ve done from circa 1953 Columbia DJ vinyl 78s, which I recently purchased in mint condition. Best heard using PRO LOGIC decoding – but fully compatible for stereo or mono repro.” No Garland studio session has ever been issued in surround sound. After leaving MGM in 1950, Garland had no record contract until Mitch Miller at Columbia records signed her in 1953 for these four sides, all done on April 3, 1953 in three hours and thirty takes. Columbia also released the A Star is Born sound track on various formats. Chapter 18, The Man That Got Away, from A Star is Born, is another Garland classic. After four takes, this dramatic version was preferred by Garland over a lower keyed version preferred by vocal coach Hugh Martin, who left the film in disaccord. Judy at the Palace, Chapter 19, is from Garland’s first Capitol LP in 1955. First sung by her in 1951 for her first appearance at The Palace in New York, it commemorates performers who played the theater when it was a vaudeville Mecca. It includes the English adaptation of Mon homme, popularized in America by Fanny Brice. Chapter 20, Memories of You, is from her second Capitol LP in 1956.

CD II contains radio performances recorded live between 1935 and 1951. All but one (Chapter 2) are new to CD. Twelve of the selections (Chapters 1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16 (The Man I Love), 17, 18, 20) were never commercially recorded by Garland. Judy’s first known radio broadcast occurred in 1928, but it was not until she signed with MGM in 1935 that she began to be heard regularly on the air. MGM used radio to promote its latest films, and Garland performed on hundreds of broadcasts in the 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s largely for that purpose. Fortunately, she also performed many songs not in her movies. Judy Garland’s radio dates, tirelessly researched and archived by John Walther (Germany), and also Kim Lundgreen (Denmark), were recorded onto transcription discs. Many discs survive, but many of these performances exist today only on tape or CDR. Garland stopped performing live on radio in 1953, by which time television was becoming the more dominant medium in the U.S.. The fact that so many Garland radio performances have never been released so many decades after their broadcast is astounding. Among the highlights of the current collection is Broadway Rhythm, Chapter 1, which is the first extant Garland radio performance. Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart, Chapter 2, is her second extant radio performance. She would sing Smiles, Chapter 4, in the film For Me and My Gal (1942). Chapter 6, On the Bumpy Road to Love, is performed with Robert Young, Fanny Brice, Frank Morgan, Joan Crawford, and a chorus. She sang the number in the film Listen, Darling (1938). Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Chapter 7, is an excerpt from an air trailer. She sang the number in the film Everybody Sing (1938). Chapter 10, Love’s New Sweet Song, is the first time a tune written by Garland (words) and David Rose (music) has ever been released. Garland sang Minnie from Trinidad, Chapter 13, in the film Ziegfeld Girl (1941). Johnny Mercer’s affair with Garland in the early 1940s inspired him to write the lyric to That Old Black Magic, Chapter 14, here conducted by Andre Kostelanetz. The Over the Rainbow in Chapter 15 is performed with a chorus. Andre Kostelanetz, conductor here, conducted at Garland’s very first concert on July 1, 1943 at the Robin Hood Dell in Philadelphia, of which a private Studio Recording Incorporated 2-LP set surfaced in 2007.Garland sang Embraceable You, Chapter 16, in the film Girl Crazy, based on which Decca Album 362 was issued. She never filmed or commercially recorded The Man I Love. Chapter 18, Someone to Watch Over Me, was recorded for a private disc, but never broadcast. You and I, Chapter 20, is not the same song as the one of the same title heard in Meet Me in St. Louis.

Lawrence SCHULMAN

© 2008 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini SAS

CD I

01 - BLUE BUTTERFLY* (Johnny Tucker/Joe Schuster) 1929 2’01

A Holiday in Storyland, First National-Vitaphone Pictures (1930). Court métrage Technicolor bichromatique, 1 bobine. Avec “The Three Kute [sic] Kiddies” au générique, dont Frances “Baby” Gumm, soliste, du trio The Gumm Sisters. Burbank, novembre 1929. – VITAPHONE 3824.

02 - HANG ON TO A RAINBOW* (Bud Green/Sammy Stept) 1929 1’08

The Wedding of Jack and Jill, First National-Vitaphone Pictures (1930). Court métrage Technicolor bichromatique, 1 bobine. Avec The Vitaphone Kiddies au générique, dont Frances “Baby” Gumm, soliste, du trio The Gumm Sisters. Burbank, novembre 1929. – VITAPHONE 3826.

03 - STOMPIN’ AT THE SAVOY (Andy Razaf/Edgar Sampson, Chick Webb, Benny Goodman) 1936 2’25

Bob Crosby and his Orchestra. New York, 12 juin 1936. – DECCA 848 A/Matrice 61165-A.

04 - OVER THE RAINBOW (E.Y. Harburg/Harold Arlen) 1938 2’13

The Wizard of Oz (Le Magicien d’Oz), MGM (1939). M-G-M Studio Orchestra. Herbert Stothart, chef d’orchestre, arrangement. Murray Cutter, orchestration. Culver City, 7 octobre 1938. – MGM E3464 ST (1956)/montage de prises 5 + 6.

05 - I’M JUST WILD ABOUT HARRY (Noble Sissle et Eubie Blake) 1939 2’02

Victor Young and his Orchestra. Victor Young, arrangement. Hollywood, 29 juillet 1939. BRUNSWICK 02969 B/Matrice DLA 1851-A/UK (1943).

06 - BUT NOT FOR ME (Ira Gershwin/George Gershwin) 1943 3’14

George Stoll and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 2 novembre 1943. – DECCA Album 362/DECCA 23309 A/Matrice L 3250-A.

07 - HAVE YOURSELF A MERRY LITTLE CHRISTMAS (Hugh Martin et Ralph Blane) 1944 2’45

George Stoll and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 20 avril 1944. – DECCA Album 380/DECCA 23362 A/Matrice L 3387-A.

08 - ON THE ATCHISON, TOPEKA AND THE SANTA FE (Johnny Mercer/Harry Warren) 1945 3’14

Lennie Hayton, chef d’orchestre et de choeur. Conrad Salinger, orchestration. Kay Thompson Chorus. Hollywood, 10 septembre 1945. – DECCA Album 388/DECCA 23458 A/Matrice L 3958-A.

09 - WHO ? (Oscar Hammerstein II, Otto Harbach /Jerome Kern) 1945 2’49

Till the Clouds Roll By (La Pluie qui chante), MGM (1946). M-G-M Studio Orchestra and Chorus. Lennie Hayton, chef d’orchestre. Kay Thompson, arrangement vocal. Conrad Salinger, orchestration. Culver City, 9 octobre 1945. M-G-M K82 4/K30431-A/Matrice 46S3018/prise 3.

10 - YOU CAN DO NO WRONG (Cole Porter) 1947 3’03

The Pirate (Le Pirate), MGM (1948). M-G-M Studio Orchestra. Lennie Hayton, chef d’orchestre. Conrad Salinger, arrangement et orchestration. Culver City, 6 février 1947. – MGM 21/MGM 30098 B/Matrice 47S3431.

11 - I WISH I WERE IN LOVE AGAIN (Lorenz Hart/Richard Rogers) 1947 2’46

Eadie Griffith et Rack Godwin, accompagnement pianos. Hollywood, 15 novembre 1947. DECCA 24469 A/Matrice L 4565-A.

12 - BETTER LUCK NEXT TIME (Irving Berlin) 1948 3’02

Easter Parade (Parade de printemps), MGM (1948). M-G-M Studio Orchestra. Johnny Green, chef d’orchestre. Conrad Salinger et Roger Edens, arrangement. Conrad Salinger, orchestration. Culver City, 17 janvier 1948. MGM 40/MGM 30187-A/Matrice 49S3023.

13 - GET HAPPY (Ted Koehler/Harold Arlen) 1950 2’51

Summer Stock (La Jolie fermière), MGM (1950). M-G-M Studio Orchestra with male sextette. Johnny Green, chef d’orchestre. Saul Chaplin et Skip Martin, arrangement. Skip Martin, orchestration. Culver City, 15 mars 1950. MGM 56/MGM 30254 B/Matrice 50S3076/prise 12.

14 - SEND MY BABY BACK TO ME** (Jessie Mae Robinson) 1953 2’11

Paul Weston and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 3 avril 1953. Paul Weston, arrangement. COLUMBIA 40010/Matrice RHCO10464.

15 - HEARTBROKEN** (Fred Ebb et Phil Springer) 1953 2’41

Paul Weston and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 3 avril 1953. Paul Weston, arrangement. COLUMBIA 40023/Matrice RHCO10465.

16 - WITHOUT A MEMORY** (Bob Hilliard et Milton Delugg) 1953 2’48

Paul Weston and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 3 avril 1953. Paul Weston, arrangement. COLUMBIA 40010/Matrice RHCO10466.

17 - GO HOME, JOE** (Irving Gordon) 1953 3’03

Paul Weston and his Orchestra. Hollywood, 3 avril 1953. Paul Weston, arrangement. COLUMBIA 40023/Matrice RHCO10467.

18 - THE MAN THAT GOT AWAY (Ira Gershwin/Harold Arlen) 1953 3’39

A Star is Born (Une étoile est née), Warner Bros. (1954). Warner Bros. Studio Orchestra. Ray Heindorf, chef d’orchestre. Skip Martin et Ray Heindorf, arrangement et orchestration. Irving “Babe” Russin (ts), Buddy Cole (p), Hoyt Bohannon (tb), Nick Fatool, (dm). Hollywood, 4 septembre 1953. – COLUMBIA 40270/Matrice RHCO10931.

19 - JUDY AT THE PALACE (Roger Edens) 1955 6’16

Miss Show Business. 33 tours. Jack Cathcart, chef d’orchestre. Harold Mooney, arrangement. SHINE ON HARVEST MOON (Nora Bayes et Jack Norworth)/SOME OF THESE DAYS (Shelton Brooks)/MY MAN (Albert Willemetz, Jacques Charles/Maurice Yvain; paroles anglaises: Channing Pollock)/I DON’T CARE (Jean Lenox/Harry O. Sutton). Los Angeles, 29 août 1955. – CAPITOL W676/Matrice 14367.

20 - MEMORIES OF YOU (Andy Razaf/Eubie Blake) 1956 3’38

Judy. 33 tours. Nelson Riddle, chef d’orchestre, arrangement. Los Angeles, 26 mars 1956. CAPITOL T-734/Matrice 15273.

**Inédit sur CD en version intégrale/First release on CD in uncut form.

**Restauration Robert Parker (2002) inédite, DOLBY PRO LOGIC surround/Robert Parker remastering (2002) first release, DOLBY PRO LOGIC surround

CD II

01 - BROADWAY RHYTHM** (Arthur Freed/Nacio Herb Brown) 1935 3’55

Radio, 26 octobre 1935, The Shell Chateau Hour.

02 - ZING! WENT THE STRINGS OF MY HEART (James F. Hanley) 1935 3’34

Radio, 16 novembre 1935, The Shell Chateau Hour.

03 - ON REVIVAL DAY* (Andy Razaf) 1936 3’00

Radio, 6 août 1936, The Shell Chateau Hour.

04 - SMILES** (J. Will Callahan/Lee M. Roberts) 1937 2’50

Radio, 9 mars 1937, Jack Oakie’s College.

05 - MY HEART IS TAKING LESSONS* (Johnny Burke/Jimmy Monaco) 1938 2’15

Radio, 21 avril 1938, Good News of 1938.

06 - ON THE BUMPY ROAD TO LOVE* (Al Hoffman, Al Lewis, Murray Mencher) 1938 2’29

Radio, 20 octobre 1938, Good News of 1939.

07 - SWING LOW, SWEET CHARIOT* (Negro spiritual) 1938 1’50

Radio. Spot promotionel (extrait) pour le film Everybody Sing, MGM (1938).

08 - GOODY GOODBYE* (James Cavanaugh/Nat Simon) 1939 2’24

Radio, 7 novembre 1939, The Bob Hope Pepsodent Show.

09 - IN SPAIN THEY SAY “SI-SI”* (Ernesto Lecuona, Al Stillman, Francia Luban/Ernesto Lecuona) 1940 2’19

Radio, 9 avril 1940, The Bob Hope Pepsodent Show.

10 - LOVE’S NEW SWEET SONG* (Judy Garland/David Rose) 1941 1’12

Radio, 26 janvier 1941, Silver Theatre, épisode: Love’s New Sweet Song.

11 - THE THINGS I LOVE** (Harris et Barlow) 1941 2’25

Radio, 7 septembre 1941, The Chase and Sanborn Hour.

12 - DADDY** (Bob Troup) 1941 2’16

Même émission que The Things I Love.

13 - MINNIE FROM TRINIDAD* (Roger Edens) 1942 3’51

Radio, 18 juin 1942, Command Performance #18

14 - THAT OLD BLACK MAGIC* (Johnny Mercer/Harold Arlen) 1943 2’35

Radio, 4 juillet 1943, Music for a Sunday Afternoon. Andre Kostelanetz, chef d’orchestre.

15 - OVER THE RAINBOW* (E.Y. Harburg/Harold Arlen) 1943 4’14

Même émission que pour That Old Black Magic.

16 - EMBRACEABLE YOU/THE MAN I LOVE* (Ira Gershwin/George Gershwin) medley 1943 4’14

Radio, 28 août 1943, Command Performance #81.

17 - SOMEBODY LOVES ME* (B.G. De Sylva, Ballard Macdonald/George Gershwin) 1944 1’05

Radio, 11 juillet 1944, Everything for the Boys.