- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

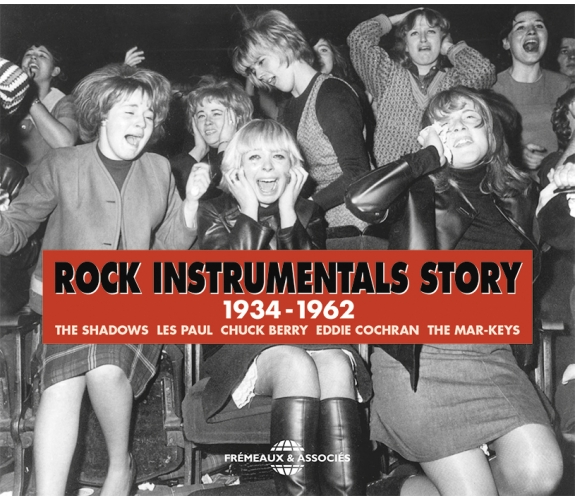

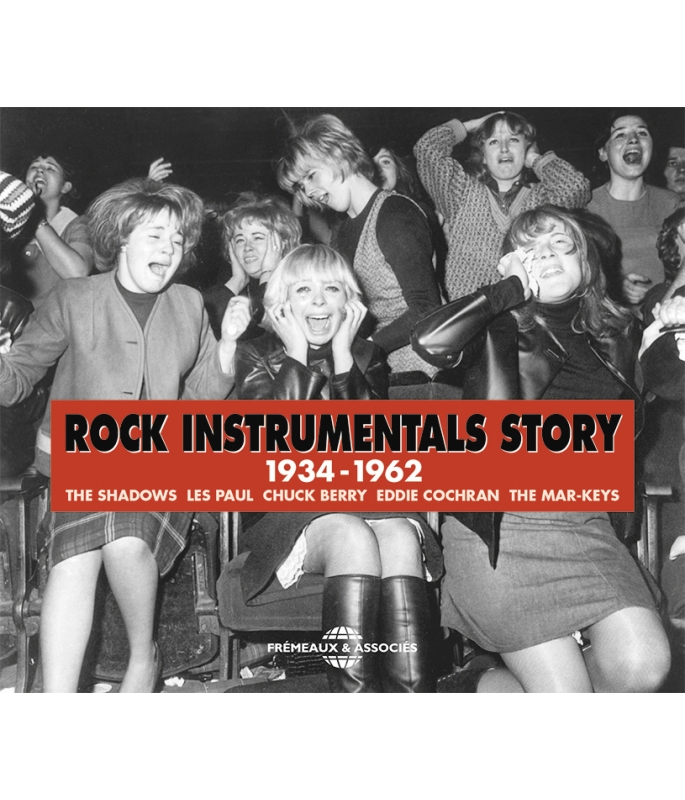

THE SHADOWS • LES PAUL • CHUCK BERRY • EDDIE COCHRAN • THE MAR-KEYS…

Ref.: FA5426

EAN : 3561302542621

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 46 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

THE SHADOWS • LES PAUL • CHUCK BERRY • EDDIE COCHRAN • THE MAR-KEYS…

THE SHADOWS • LES PAUL • CHUCK BERRY • EDDIE COCHRAN • THE MAR-KEYS…

A compulsory exercise in the careers of the greatest, instrumentals, together with brilliant improvisations based on catchy themes, have always had pride of place in rock history. This anthology retraces the different facets of their roots and evolution, from jazz and country music to the kind of rock where electric guitars play a central role. From boogie woogie to western swing, and from rhythm and blues to soul music, radio jingles, film music and surf-rock, the earliest instrumental rock classics are compiled here with the detailed comments of Bruno Blum, himself a guitarist and rockspecialist. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1An Orange Grove In CaliforniaSol Hoopii00:03:061934

-

2Boogie Woogie StompAlbert Ammons And His Rythm Kings00:03:001936

-

3Bob Will's BoogieBob Wills And His Texas Playboys00:02:441946

-

4CaravanLes Paul00:02:341947

-

5Crazy RythmBob Wills And His Texas Playboys00:01:581947

-

6Canned HeatChet Atkins00:02:351947

-

7Guitar BoogieArthur Smith00:03:261948

-

8Guitar BoogieHarry Crafton00:02:341949

-

9Cannonball StompMerle Travis00:01:291949

-

10The Big Three StompThe Big Three Trio00:03:061949

-

11Strollin' With BonesT-Bone Walker00:02:321950

-

12Longhair StompRoy Byrd And His Blues Jumpers00:02:501950

-

13Rockin' The Blues AwayTiny Grimes Quintet00:02:571951

-

14Kohala MarchSol Hoopii00:02:391951

-

15Guitar ShuffleLowell Fulson00:02:481951

-

16Midnight RambleSpeedy West & Jimmy Bryant00:01:561952

-

17NuagesDjango Reinhardt00:03:181953

-

18Oh By Jingo !Chet Atkins00:02:151953

-

19The HucklebuckEarl Hooker00:03:101953

-

20Space GuitarYoung John Watson00:02:411954

-

21Walking The StringsMerle Travis00:01:561954

-

22The ThingLafayette Thomas00:02:131953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Boogie RockBB King00:03:031955

-

2Honky TonkBill Doggett00:05:411956

-

3Spinnin Rock BoogieMickey Baker00:02:221956

-

4The Rocking GuitarCecil Campbell00:01:541957

-

5RauchyBill Justis00:02:241957

-

6RumbleLink Wray And His Ray Men00:02:291957

-

7TequilaThe Champs00:02:141957

-

8In GoChuck Berry00:02:301957

-

9Guitar BoogieChuck Berry00:02:211957

-

10Rebel RouserDuane Eddy00:02:251958

-

11Dixie DoodleLink Wray And His Ray Men00:02:111959

-

12Raw HideLink Wray And His Ray Men00:02:081959

-

13Guitar Boogie ShuffleThe Virtues00:02:391958

-

14Strollin GuitarEddie Cochran00:01:551959

-

15Red River RockJonnhy And The Hurricanes00:02:151959

-

16Mumblin' GuitarBo Diddley00:02:511959

-

17GuyboEddie Cochran00:01:491959

-

18Storm WarningDr John00:02:531959

-

19Sleep WalkMike Dee And The Mello Tones00:02:241959

-

20Bongo RockPreston Epps00:02:121959

-

21Peter GunDuane Eddy00:02:201959

-

22Chicken Shot BluesEddie Cochran00:03:051959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Walk Don't RunThe Ventures00:02:071959

-

2Travelin' WestBo Diddley00:01:481960

-

3SilkyClue J And His Blues Blasters00:02:511960

-

4ApacheThe Shadows00:02:571960

-

5WheelsThe String a Longs00:01:581960

-

6Ghost Riders In The SkyThe Ramrods00:02:411960

-

7Quick DrawBo Diddley00:01:561961

-

8Lullaby Of The LeavesThe Ventures00:02:021960

-

9Hide AwayFreddie King00:02:381960

-

10Bumble BoogieB Bumble And The Stringers00:02:121961

-

11Mashed Patato TwistBB King00:02:291961

-

12Last NightThe Mar-Keys00:02:361961

-

13BulldogThe Ventures00:02:271961

-

14MiserlouDick Dale And The Del Tones00:02:141962

-

15Soul TwistKing Curtis And The Noble Knights00:02:391961

-

16Nut RockerB Bumble And The Stringers00:02:011961

-

17Give Me A BreakBo Diddley00:02:071962

-

18FrostyAlbert Collins00:03:051962

-

19Let's Go PonyThe Routers00:02:211962

-

20DiddlingBo Diddley00:02:151962

-

21Green OnionsBooker T And The MG's00:02:531962

-

22PipelineThe Chantays00:02:181962

Rock instrumental story FA5426

ROCK INSTRUMENTALS STORY1934-1962

THE SHADOWS LES PAUL CHUCK BERRY EDDIE COCHRAN THE MAR-KEYS

ROCK INSTRUMENTALS Story

1935-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Note : forcément non exhaustif, cet album peut être complété par plusieurs anthologies dans cette collection1.

La voix est vraisemblablement le premier instrument de musique jamais utilisé par nos ancêtres les plus lointains. On peut d’ailleurs entendre quelques brèves interventions de voix ici, sur Crazy Rhythm, Give Me a Break, Tequila, (Ghost) Riders in the Sky, ou Let’s Go. Néanmoins depuis la nuit des temps il existe dans toutes les cultures du monde des musiques instrumentales sans voix ou presque. Les instruments de musique peuvent produire des émotions et des sons inaccessibles aux cordes vocales : des délicates musiques zen japonaises à la longue tradition juive du klezmer, des tambours ingoma du Burundi aux fanfares militaires allemandes, des compétitions de la volcanique samba brésilienne à la délicate sophistication des « Préludes » dissonants d’Achille-Claude Debussy, de la cacophonie démente des flûtes de Joujouka au Maroc jusqu’aux sublimes improvisations de Jimi Hendrix (« Drivin’ South », « Star Spangled Banner », « Villanova Junction ») qui atteignaient le cœur du réacteur — des myriades de musiques instrumentales d’une grande diversité résonnent depuis des millénaires sur les tympans des terriens.

Rock Instrumental

Le rock a toujours connu un versant instrumental, une tendance qui devint une mode lancée à la fin des années 1950. Elle se répandit sous l’influence de guitaristes essentiels comme Sol Hoopii, T-Bone Walker, Charlie Christian, Arthur Smith, Chet Atkins, Earl Hooker, Billy Butler avec l’organiste Bill Doggett, puis des formations entièrement consacrées au rock instrumental comme celles de Link Wray, Duane Eddy, Dick Dale et les Ventures. Devenu un style à part avec ces formations sans chanteur comme Johnny and the Hurricanes ou les Britanniques des Shadows, l’instrumental rock deviendra un passage obligé pour nombre de groupes chantants (« Stoned » ou « 2120 South Michigan Avenue » des Rolling Stones en 1964, « Flying » des Beatles en 1967, « Woodchopper’s Ball » de Ten Years After en 1967, etc.) et s’essoufflera à la fin des années 1960. Cette anthologie retrace les différentes facettes de ses racines et son évolution, du jazz à la country music jusqu’au rock, où la guitare électrique tient une place centrale.

Origines

Avec la popularité du jazz, qui a commencé à conquérir le grand public nord-américain dans les années 1930, des pièces instrumentales où l’improvisation tient une grande place visaient à faire danser les auditeurs : ce fut la période « swing » des années 1930-1940. Ce lien conceptuel à la danse, s’il est loin d’être exclusif aux musiques afro-américaines, est indissociable du rock, une musique fondamentalement dérivée du jazz et de son incarnation «jump blues» des années 1940 en particulier.

Si l’improvisation existe dans nombre de musiques du monde entier, la mise en valeur des interprètes, des musiciens qui deviennent solistes le temps d’une intervention, est un trait caractéristique du jazz, de beaucoup de musiques afro-américaines et caribéennes, pour ne pas dire africaines. Cette richesse instrumentale plonge ses racines à la fois dans les traditions africaines et l’histoire de l’oppression des Afro-américains. Les negro spirituals, ou chansons d’esclaves, étaient à l’origine l’expression des expériences, des forces et des espoirs de millions d’Africains déportés aux Amériques et réduits à la servitude2. C’est dans diverses formes de transe 3, quête de lien avec les ancêtres dans nombre de religions animistes ouest africaines (Akan, Yoruba, Bantou notamment), que les musiques rythmées induisaient une extase de nature spirituelle propice à improviser de mystérieux messages chantés, inspirés par les esprits3. Schématiquement, après l’abolition de l’esclavage en 1865, ces improvisations inspirées, où l’interprète était déterminant, se sont fondues dans la musique populaire et ont été formulées par des instruments de musique (initialement piano, orgue, trompette, saxophone, etc.), donnant ainsi naissance au jazz. La mode de la danse charleston des années 1920 en fut une concrétisation. Incitant le public à participer à l’excitation collective, à la danse libre, à l’expression des corps et des esprits unis et révélés par le rythme, le jazz était souvent chanté, mais des milliers de magnifiques enregistrements témoignent de sommets musicaux instrumentaux à 100%.

Jazz Instrumental

Les origines du « rock instrumental » sont à chercher dans le jazz, musique instrumentale d’improvisation par excellence4. Au cours de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, la mode du « swing » dansant anticipait déjà le rock. L’une des formes de ce jazz était le boogie woogie, au rythme particulièrement irrésistible5 qui à l’évidence est à la racine du rock. Un exemple convaincant est ici le Boogie Woogie Stomp du pianiste Albert Ammons, dont le swing ou « groove » de 1936 rappellera étrangement, près de trente ans plus tard, le « Now I’ve Got a Witness » (1964) et autres « Andrew’s Blues » des Rolling Stones débutants. Après le concert « From Spirituals to Swing » à Carnegie Hall (auquel Ammons participa en en 1938), le style boogie woogie fut particulièrement populaire au cours de la période étiquetée « swing » (balancement) dans le jazz d’avant-guerre, puis pendant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Emportés par le rythme, ses créateurs étaient capables de réaliser des enregistrements aux arrangements d’une grande sophistication, conçus par des musiciens comme Duke Ellington, qui étaient traversés par des fulgurances géniales où l’improvisation fournissait des moments de grâce, d’ivresse, de liberté à d’anonymes musiciens soudain mis en valeur6 par un orchestre entier.

Le swing et le boogie woogie évolueront bientôt vers le style jump blues, qui fut la forme originelle du rock (Louis Jordan, Jay McShann, Big Joe Turner, Doc Pomus, Wynonie Harris, etc.). La mode swing alimentera aussi des orchestres très populaires auprès du public blanc, comme celui de Glenn Miller, qui n’employaient pas ou peu de musiciens noirs (c’était difficile en raison des préjugés et lois de ségrégation raciale), n’incluaient que rarement des improvisations dans leurs enregistrements et reprenaient à leur compte les idées de créateurs afro-américains. Si leur amour du jazz était sincère et leurs enregistrements valables, l’histoire a souvent retenu d’eux cet aspect commercial de la « dance music » d’alors.

Certains musiciens de jazz se sont tournés vers la guitare électrique. Basé à Paris, l’extraordinaire Manouche Django Reinhardt fut bien sûr le guitariste qui domina l’avant-guerre avec sa guitare sèche Selmer-Maccaferri. Son influence fut immense sur tout ce que le monde comptait alors comme guitaristes. La période électrique de la fin de sa vie (1953) est moins connue mais elle a ajouté une pierre à l’édifice des thèmes célèbres interprétés à la guitare électrique. Suite logique, le rock instrumental prendra véritablement son essor peu après cette période très jazz. L’influence de T-Bone Walker7 et Charlie Christian8 pendant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale a sans doute le plus contribué à populariser la guitare électrique, qui s’est invitée dans tous les styles de musique populaire dès le début des années 1940. L’influence du jazzman virtuose Les Paul a aussi beaucoup joué quand, au début des années 1950, il est devenu une vedette de la télévision en interprétant des sketchs et chansons de variété où ses nombreuses innovations à la guitare électrique tenaient une grande place. L’interprétation par des jazzmen de thèmes célèbres à la guitare électrique précède et annonce en fait le « rock instrumental » : Les Paul (Caravan), Django Reinhardt (Nuages) en sont des exemples de choix.

Country Music

Le boogie woogie et le jazz « swing » ont nourri des instrumentistes venus d’autres horizons encore. Venu de l’océan Pacifique, le Hawaïen Sol Hoopii exerça une influence centrale sur la guitare steel, qui sera très présente dans la country, le western swing (écouter ici Bob Wills) et le country boogie (ici Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant) jusqu’au «slow» Sleep Walk de Santo & Johnny en 1959. Grand improvisateur sur un instrument bien à part, il fut sans doute le plus brillant de ceux qui firent découvrir la culture hawaïenne aux États-Unis, où il eut beaucoup de succès dès 1925. Il enregistrait initialement sur une guitare d’acier « lap steel » (à plat sur les genoux) non électrique que l’on peut entendre ici sur le titre ouvrant ce coffret, le très original An Orange Grove in California (1934). Sol Hoopii fut l’un des premiers à se convertir en 1935 à la guitare lap steel électrique. Cet instrument révolutionnaire donnera vite naissance à la guitare électrique proprement dite9. Son brillant Kohala March fut l’un de ses titres électriques les plus influents sur les guitaristes steel de la country music qui a suivi10. Dès les années 1930, des artistes de bal populaire comme Milton Brown & his Musical Brownies et Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys ont eux aussi adopté la lap steel et le swing très dansant qu’ils entendaient dans le jazz11. Leur style texan, le western swing, se différenciait de la country music ambiante par son énergie et son incitation à danser « swing ». Il constitue l’une des racines du rock comme on peut l’entendre ici haut et fort. Des titres western swing comme Bob Wills’ Boogie et Crazy Rhythm participeront à inspirer plusieurs artistes de country qui se pencheront à leur tour sur des musiques « swing » comme le boogie woogie. Le style «hillbilly boogie » ou « country boogie » qui a résulté de ces influences fait l’objet d’une anthologie dans cette collection12. L’un des grands classiques du country boogie est bien sûr le célèbre Guitar Boogie d’Arthur Smith and his Cracker-Jacks, dont il existe deux versions (la première date de 1945 et la plus connue des deux, numéro 9 des ventes country en 1948, est incluse ici). Né dans une famille de musiciens de Caroline du Sud puis installé en Caroline du Nord à 400km de Nashville, Arthur Smith a participé à construire le son de la country music d’après-guerre. Une reprise de son gros succès par The Virtues (alias The Virtuoso Trio) dix ans après est même incluse ici : Guitar Boogie Shuffle obtint lui aussi de grosses ventes. Plusieurs titres de rock instrumental noir, sans rapport direct avec ce titre, porteront ensuite le nom de Guitar Boogie notamment par Henry Crafton en 1949 et Chuck Berry en 1957.

Le son country de Nashville dans l’après-guerre a été dominé par le monstre sacré de la guitare Chet Atkins, qui fut élevé dans la misère et chercha rédemption dans un travail acharné sur son instrument. On peut l’écouter ici briller sur Canned Heat (guitare sèche) et six ans plus tard sur sa Gretsch électrique dans l’excellent Oh by Jingo!.Virtuose, Chet Atkins a formé son difficile style de finger picking à quatre doigts en se basant sur celui de Merle Travis (qui utilisait son pouce et son index), un autre géant de la country élevé au Kentucky un peu au nord de Nashville. Merle Travis était très influencé par le maître de la guitare ragtime, Blind Blake. L’influence de ces trois guitaristes à la racine du rock est incalculable. Merle et Chet marqueront notamment Scotty Moore avec Elvis Presley13 ainsi que tout l’influent rockabilly14 — et avec lui le rock qui suivra, des Beatles à Jeff Beck et de Creedence aux Stray Cats. On peut apprécier ici la qualité de leurs enregistrements remarquables et leur influence sur un titre de Carol Dills aussi obscur qu’appréciable, The Rocking Guitar sorti en face B d’un rockabilly de Cecil Campbell en 1956.

Blues & Rock n’ Roll

Si l’importance, l’influence et le talent de musiciens de country comme Arthur Smith, Merle Travis, Chet Atkins ou Jimmy Bryant ne peuvent être mis en question, la multiplication de morceaux instrumentaux de grande qualité dans le jazz, le blues et le rhythm and blues affichent une richesse insurpassable, expression éminente d’une culture afro-américaine tournée vers le coup d’éclat musical. Dans le domaine du rock instrumental comme dans d’autres champs musicaux américains, la contribution créative de la minorité afro-américaine est incomparable. Il était courant dans les années d’après-guerre qu’une séance d’enregistrement s’achève par la prise d’un instrumental, souvent improvisé à l’emporte-pièce sur douze mesures de blues. Le morceau supplémentaire pouvait ensuite servir pour la face B d’un disque et, dans certains cas, pour la face A. C’est peut-être comme ça que sont nés le Guitar Boogie d’Henry Crafton ou le Big Three Stomp du Big Three Trio (un des premiers groupes de Willie Dixon). En 1950, bien avant les premiers succès d’Elvis Presley, le rock était déjà à la mode dans la communauté noire comme le rappelle Tiny Grimes et son splendide Rockin’ the Blues Away. Tiny Grimes et sa guitare électrique à quatre cordes ont enregistré avec les plus grands jazzmen, de Charlie Parker à Art Tatum, mais Tiny était parallèlement le leader d’un groupe de rock, les Rocking Highlanders, qui enregistrèrent souvent dans ce style autour de 1950. En réalité le « jazz » est un terme passe-partout qui inclut quantité de différents styles, à commencer par le rock lui-même dans sa forme originelle, le « jump blues » d’après-guerre. Les cuivres étaient encore omniprésents dans le jump blues, comme on l’entend ici chez les guitaristes T-Bone Walker, Harry Crafton, Tiny Grimes, Lowell Fulson ou B.B. King, qui excelle ici sur Boogie Rock et Mashed Potato Twist. L’omniprésence d’une guitare électrique n’est pas pour autant indispensable pour qu’un lien « rock » soit avéré, comme en attestent ici les titres des pianistes Albert Ammons (dès 1936), Professor Longhair, Bo Diddley avec Otis Spann (Travelin’ West) ou B. Bumble and the Stingers. Sur Last Night et Green Onions, c’est plutôt l’orgue électrique qui domine.

Il n’en reste pas moins qu’après quelques autres perles dans une veine bluesy comme le Guitar Shuffle de Lowell Fulson, c’est à Chicago qu’Earl Hooker a enregistré son gros succès The Hucklebuck. En 1953, ce titre a véritablement ouvert la porte au rock instrumental et a contribué à mettre la guitare électrique sur un piédestal qu’il ne quitterait plus jusqu’au triomphe des claviers, samplers et autres appareils numériques trente ans plus tard. Le rock instrumental s’est répandu dans la musique populaire états-unienne et jamaïcaine au fil des années 195015 et l’histoire du rock s’est construite essentiellement autour de l’essor de la guitare électrique. Dans ces années 1950 où elle prenait le dessus avec des sons nouveaux, le rock afro-américain rayonnait dans différentes directions, variées et inventives. Les improvisations instrumentales à la guitare sont devenues un passage obligé pour les bluesmen solistes — comme pour les guitaristes de country d’ailleurs. L’un des plus étonnants morceaux de ce coffret est le Space Guitar de Johnny « Guitar » Watson, la future star du funk qui fait ici usage d’effets de son de manière radicale et très innovante. Il est difficile de croire que ce tour de force a été gravé en février 1954, des mois avant que Chuck Berry ou Bo Diddley n’aient encore fait leurs débuts en studio. D’autres perles ont surgi, comme le Spinnin’ Rock Boogie de Mickey Baker, guitariste de Ray Charles, des séances Atlantic en général (et bien d’autres) qui comme Les Paul avant lui a monté un numéro de music hall où la guitare était mise en valeur (Mickey & Sylvia). Quant au guitariste Lafayette Thomas (The Thing), il enregistra dès 1948 et tout au long des années 1950 avec Jimmy McCracklin’s Blues Blasters — qui outre leurs mérites musicaux inspirèrent leur nom au groupe jamaïcain Clue J and his Blues Blasters, représenté ici avec une intervention du guitariste Ernest Ranglin, géant des studios jamaïcains. On peut découvrir d’autres instrumentaux (avec et sans Ernest Ranglin) de ce type sur plusieurs anthologies consacrées à la Jamaïque dans cette collection16. Le succès grand public (comprenez le public blanc) du Honky Tonk de l’organiste Bill Doggett, où le méconnu Billy Butler brille à la guitare, rendait l’enregistrement de morceaux instrumentaux de plus en plus incontournables. D’autres artistes de ce que Chuck Berry appelait le boogie woogie (Berry préférait ce terme plus musicologique aux très galvaudés « rock » ou « rhythm and blues ») se sont donc essayés à des morceaux sans voix. À commencer par le maître Chuck Berry lui-même, notamment avec les exquis In-Go et Guitar Boogie (dont les Yardbirds avec Jeff Beck enregistreront plus tard une version inoubliable). Le prolifique Bo Diddley a accumulé les tours de force instrumentaux, comme en attestent ici ses irrésistibles et très originaux Mumblin’ Guitar, Travelin’ West, Quick Draw, Give Me a Break et Diddling. D’autres instrumentaux de Chuck Berry et Bo Diddley (qui en 1964 enregistreront ensemble un album instrumental, Two Great Guitars) figurent sur les triples albums qui leur sont consacrés chez Frémeaux et Associés17. Storm Warning (avec Dr. John à la guitare) et le Guybo d’Eddie Cochran sont bien sûr très influencés par Bo Diddley. D’autres afro-américains venus du blues ont enregistré des instrumentaux à succès, parmi lesquels B.B. King, Freddie King et Albert Collins, qui ont tous trois influencé Jimi Hendrix — tout comme Johnny « Guitar » Watson. Si l’on écoute l’instrumental « Drivin’ South » (1967) de l’ultra influent Jimi Hendrix qui avait vingt ans en 1962, on y décèle une nette influence du Frosty et du « Tremble » d’Albert Collins18, tous deux du début des années 60.

Soul & Funk

Le rock instrumental a aussi contribué à nourrir la soul music naissante, et par extension le funk créé dans les années 1960 par James Brown, les Meters et quelques autres. Très populaire sur les pistes de danse, Last Night a été le premier succès composé et interprété par de jeunes musiciens, les Mar-Keys, qui par la suite ont beaucoup contribué au développement du style soul. En s’adjoignant Booker T. Jones, ils ont formé en 1962 Booker T. and the M.G.’s, qui deviendra aussitôt le groupe maison de la meilleure écurie soul du sud des États-Unis : Stax Records. Avec l’efficace Steve Cropper à la guitare, Al Jackson à la batterie et Duck Dunn à la basse, l’organiste Booker T. n’avait que dix-sept ans sur leur grand classique Green Onions. Avec Billy Butler à la guitare, le saxophoniste King Curtis est lui aussi devenu l’un des leaders des musiciens de la soul. Son équipe figure sur nombre de chefs-d’œuvre du genre enregistrés pour les disques Atlantic et comme Booker T. and the M.G.’s, il a lui aussi été capable de trouver le succès avec quelques instrumentaux, dont le groovy Soul Twist. Quant à Preston Epps, son Bongo Rock a été produit par Art Laboe, le DJ qui a inventé l’album compilation. Ce morceau sera repris sous le nom de « Bongo Rock ‘73 » par The Incredible Bongo Band, qui en a fait un classique du hip hop, samplé par des dizaines d’artistes, dont le Jamaïcain Kool DJ Herc, fondateur du genre hip hop. Rappelons aussi que les rythmiques bizarres de Bo Diddley, comme ici Travelin’ West ou Diddling, ont aussi participé à élaborer le style des rythmiques de la soul, un style pourtant dérivé du gospel — donc fondamentalement chanté.

Musique de film

Les styles de piano ragtime, boogie woogie et stride étaient très populaires entre-deux-guerres. Ils participèrent notamment à l’essor du cinéma. Dès les années 1920, des pianistes ou de petites formations de jazz étaient engagés par les producteurs pour jouer au cours des tournages de films muets. Ils étaient chargés de mettre les acteurs dans l’ambiance requise par le réalisateur — comédie ou drame — et avec leur musique, de rythmer la cadence du spectacle. Cette pratique s’est vite étendue à la projection des films en salle afin que le public soit lui aussi aidé à entrer dans l’ambiance : les films muets sont depuis associés à ces styles de piano jazz qui entraient dans les salles pour y apporter un air de fête. Le principe s’est développé pour devenir bientôt une musique « d’ambiance » que l’on enregistrait et diffusait pendant le film en plus du thème associé au générique. À partir de 1945 des éditeurs ont constitué des sonothèques où des musiques pré-enregistrées pouvaient être louées ou achetées sur le champ pour être utilisées dans la bande musicale des films, ce qui évitait tout le processus de production à leurs clients. Des disques de ce type sont apparus sous l’étiquette « mood music » et avec l’apparition de l’album vinyle microsillon dans les années 1950, ce concept « ambient music » a été largement développé par le chef d’orchestre Paul Weston (Music For Dreaming, Music For the Fireside), suivi par Jackie Gleason (Music for Lovers Only) et en Angleterre par Ray Martin, Mantovani et bien d’autres. Cette musique de fond sans heurts appelait à une sophistication qui mena parfois à des excès où l’utilisation d’arrangements de violons atteint des summums de mauvais goût et d’ennui (marques Musak, Reditune). Plus dynamiques, le jazz et le rock étaient parfois utilisés comme alternative à ces stéréotypes musicaux surannés, notamment quand le film mettait en scène la jeunesse. Le rock a logiquement servi d’illustration musicale à de nombreux films et séries télé. Le rock instrumental s’y prêtait particulièrement. Citons Because They’re Young (Paul Wendkos, 1960) avec Duane Eddy : extrait de la bande du film, le morceau du même nom a été son plus gros succès et sa carrière est liée à ses musiques de films. Le rock instrumental de cette période continuera à trouver par la suite une place conséquente dans des longs métrages dépeignant de jeunes personnages. Il restera un code musical évoquant la charnière des années 1950-60. Citons Miserlou de Dick Dale and the Del-Tones utilisé dans Pulp Fiction de Quentin Tarantino (1994) ou Nut Rocker de B. Bumble and the Stingers dans Big Momma’s House de Raja Gosnell (2000).

Dans les années 1960, l’influent style de guitare au son clair avec effet de réverbération entendu ici chez Duane Eddy (guitare Gretsch 6120), les Ventures (guitares Mosrite), Dick Dale (Fender Stratocaster) ou les Shadows (Fender Stratocaster) marquera les arrangements de plusieurs musiques de classiques du cinéma. On le retrouvera par exemple dans le célèbre « James Bond Theme » (1962) de John Barry ou encore « Le Bon, la brute et le truand » (1966) d’Ennio Morricone.

Far West

Comme on l’a vu plus haut, la country music a été considérablement influencée par la musique hawaïenne (et Sol Hoopii en particulier) en vogue dans les années 1920-1930, ce qui a impulsé et précédé l’invention de la guitare lapsteel électrique puis de la pedal steel. Rappelons que le surf est une discipline née à Hawaï, où la guitare est jouée assidûment depuis le XIXème siècle. Parallèlement la guitare électrique au son clair, jouée sans distorsion en utilisant le micro aigu à simple bobinage (Fender, Teisco, Mosrite, Danelectro) est un héritage de la country music, notamment d’Arthur Smith (ici à la guitare sèche), Merle Travis (ici une Gibson Super 400), Joe Maphis (double manche Mosrite), Jimmy Bryant, Grady Martin et Chet Atkins (guitares Gretsch — le modèle 6120 « Chet Atkins » est sorti en 1955). Tous utilisaient ce type de son tranchant, net, propre, que l’on retrouve dans le rockabilly19. Il contraste avec la distorsion «sale» présente chez la plupart des bluesmen, de Johnny «Guitar» Watson à Mickey Baker et jusqu’à B.B. King ou Albert Collins. C’est sans doute Bill Justis qui avec Raunchy en 1957 a été le premier à évoquer avec succès l’ambiance « far west » avec des instrumentaux country-rock. C’est en jouant « Raunchy » à John Lennon que George Harrison a été engagé dans les Beatles. Les allusions au far west incluent ici le fameux Tequila des Champs, les Quick Draw et Travelin’ West de Bo Diddley, le Wheels des String a Longs, Let’s Go (Pony) des Routers et le (Ghost) Riders in the Sky des Ramrods, qui évoque une apparition de cavaliers fantômes dans le ciel — sans oublier le célèbre Apache des Shadows.

Surf rock

Quand elle a finalement déferlé sur le grand public blanc avec le succès phénoménal d’Elvis Presley en 1956-1957, la musique rock était très connotée « mauvais garçon », ce qui posait beaucoup de problèmes aux musiciens. Malgré tout, sa popularité a logiquement engendré une vague de rock instrumental, initialement incarnée par le séduisant Duane Eddy dont le premier succès s’appelait fort à propos Rebel Rouser en 1958. Peu après, son adaptation du thème d’une série télévisée policière, Peter Gunn, ajouta à son image superficiellement rebelle. Le son et le style originaux de Duane Eddy, dérivés de la guitare country très propre et des succès « far west » précéda la mode du surf rock, dont il fut en quelque sorte le pionnier. Link Wray en fut l’outsider. Indien Shawnee amputé d’un poumon (il ne pouvait donc pas chanter) à la suite d’une tuberculose, son étonnant Rumble (« bagarre de rue » en argot américain) a secoué le monde du rock et s’est vendu à des milliers d’exemplaires. Son succès s’est produit contre toute attente, car ce morceau menaçant allait à contresens de toute l’industrie du disque qui en 1958 cherchait désespérément à donner au rock une image plus rassurante. Link Wray l’influent inventeur du « power chord » a séduit Pete Townshend des futurs Who, qui s’est aussitôt décidé à apprendre à jouer de la guitare électrique. Trois titres de ce musicien au style aussi brut que décisif, loin des stéréotypes du « surf rock », sont inclus ici.

Eddie Cochran fut avec Bill Haley20 l’un des premiers rockers blancs à s’essayer au genre instrumental. Il jouait lui aussi sur une Gretsch 6120, le modèle favori de Brian Setzer qui en 2011 a enregistré un remarquable album de guitare rock entièrement instrumental très marqué par les années 1950. Eddie Cochran, le héros de jeunesse de Setzer, est représenté ici avec trois morceaux. Son Strollin’ Guitar est caractéristique du son « surf » de cette période. Son Chicken Shot Blues n’est en revanche qu’une jam session révélant un style de guitare très agressif qui rappelle peut-être celui de Jimmy Page avec Led Zeppelin dix ans plus tard. L’association du rock instrumental avec le surf n’est véritablement avérée qu’à partir du succès de Dick Dale and his Del-Tones et leur morceau Miserlou en 1962. Marqué par la musique orientale (plus une trompette mexicaine), ce titre est basé sur une mélodie traditionnelle du Moyen-Orient arrangée en rock (sur le même principe que les deux titres de Bumble and the Stingers adaptés de thèmes de musique classique, comme le feront dix ans plus tard avec brio les Néerlandais de Ekseption). À l’été 1961 les concerts de Dick Dale (d’origine libanaise) refusaient du monde au Rendezvous Ballroom de la plage de Balboa au sud de Los Angeles, près du spot The Wedge, haut-lieu du surf. Dick Dale pratiquait le surf et une photo de lui en action sur une vague ornait la pochette de son premier album Surfer’s Choice. D’autres groupes, comme les Bel-Airs (« Mr. Moto », 1961), les Challengers (album Surfbeat, 1962), les Surfaris (« Wipeout », 1963) ou encore Eddie and the Showmen ont participé à la vogue initiale du « surf rock » en Californie du Sud. Originaires de Santa Ana, à côté de Balboa, avec leur énorme succès Pipe Line enregistré selon la légende dans l’arrière-boutique d’un magasin de surf, les Chantays faisaient allusion aux « pipelines », ces tunnels formés par les rouleaux de grandes vagues que les surfeurs les plus audacieux sont capables d’emprunter. Mais tous, Dick Dale compris, devaient leur approche du son de guitare (clair avec réverb et micro aigu) au groupe de rock instrumental le plus important de cette époque, les célèbres Ventures. Avec Walk Don’t Run (1960), « Perfidia », « Driving Guitars », Bulldog, Lullaby of the Leaves, les Ventures ont été les premiers à imposer la formule rock originale qui consiste à arranger en rock des mélodies connues, venues de tous les horizons. Initialement chanté par Ina Hayward, « Lullaby of the Leaves » provient d’une revue sans succès à Broadway, Chamberlain’s Brown Scrap Book (1932). Il fut interprétée à la radio par l’orchestre de Freddie Berrens et enregistré par Ben Selvin et Connie Boswell avant de devenir un standard du jazz. Originaires de Tacoma près de Seattle, les Ventures enregistraient aussi des versions des rocks instrumentaux les plus populaires. Ils ont plus tard repris avec talent nombre de titres figurant ici.

Avec des dizaines d’albums à leur actif et un succès aussi record qu’increvable, ils restent sans doute le plus grand groupe de rock instrumental de l’histoire. Les Shadows ont copié leur son en Angleterre, tout comme Dick Dale, les Chantays, les Routers et tant d’autres, dont les Beach Boys, un groupe vocal qui utilisait aussi ce son de guitare «surf» particulier.

Un nombre considérable d’autres groupes de rock graveront des morceaux très influencés par les Ventures de Bob Bogle et Nokie Edwards, parmi lesquels les Spotnicks (« Orange Blossom Special », 1961) à Stockholm, les Trashmen (« Malaguena », 1964) à Minneapolis, les Flying Padovanis (« Western Pasta », 1981) à Londres et bien sûr le premier enregistrement en studio des Beatles à Hambourg en 1961, « Cry for a Shadow » sorti en 1964.

Bruno Blum

Merci à Denis « Chourave » Bouillet, Yves Calvez, Stéphane Colin, Gilles Conte, Bo Diddley, Henry Padovani, Vincent Palmer, Jérôme Piel d’Arc, Gilles Pétard, Brian Setzer et Michel Tourte.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz Blues R&B Rock 1935-1962 (anthologie de Bruno Blum, FA5421) et Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (par Gérard Herzaft, FA5007) contiennent en partie des morceaux chantés mais on y trouve aussi des instrumentaux de Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, Chuck Berry, Bob Wills, Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant, Floyd Smith, Alvino Rey et bien d’autres (consulter fremeaux.com). Notre série de trois albums Boogie Woogie Piano présentée par Jean Buzelin (FA036, FA5164, FA5226) présente aussi des liens thématiques avec cet album.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA5467) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica Folk, Trance Possession 1939-1961 (FA5384) dans cette collection, et «Pukkumina Cymbal» en particulier.

4. Lire le livret et écouter The Best Small Jazz Bands 1936-1955 (FA5194) dans cette collection.

5. Lire les livrets et écouter nos trois volumes Boogie Woogie Piano (FA036, FA5164, FA5226) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter The Greatest Black Big Bands 1930-1956 (FA5287) dans cette collection.

7. Lire le livret et écouter T-Bone Walker – The Blues – Father of the Modern Blues Guitar 1929-1950 (FA 267) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Charlie Christian - The Quintessence 1939-1941 (FA218) dans cette collection.

9. Voir Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

10. Retrouvez Sol Hoopii sur l’anthologie Electric Guitar Story (FA5421) dans cette collection, sur Hawaiian Music Honolulu-Hollywood-Nashville 1927-1944 (FA035) et sur Rock n’ Roll Vol. 1 - 1927-1938 (FA351).

11. Retrouvez Milton Brown et Bob Wills sur l’anthologie Western Swing 1928-1944 (FA032) dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à la l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA5361) dans cette collection. Les versions originales des morceaux repris par Elvis Presley y sont incluses mettent en évidence ses influences.

14. Lire le livret et écouter Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5426) dans cette collection.

15. Lire les livrets et écouter dans cette collection Jamaica Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA5358) et Roots of Ska - Rhythm and Blues Shuffle USA & Jamaica 1942-1962 (FA5396) qui contiennent plusieurs instrumentaux.

16. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA5358), USA-Jamaica Roots of Ska — Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396) et Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5358) dans cette collection.

17. Lire les livrets et écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409), The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et Volume 2 1959-1962 (FA5406) dans cette collection.

18. Retrouvez le «Tremble» d’Albert Collins sur Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz Blues R&B Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

19. Lire le livret et écouter Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423) dans cette collection.

20. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

ROCK INSTRUMENTALS Story

1935-1962

By Bruno Blum

Note: this selection is inevitably non-exhaustive but the album is complemented

by several other anthologies in this series.1

The voice was probably the first musical instrument ever used by our most distant ancestors. By the way you can actually find a few short vocal appearances here on instrumentals like Crazy Rhythm, Give Me a Break, Tequila, (Ghost) Riders in the Sky or Let’s Go. Nevertheless since the dawn of time, in every culture in the world, instrumental music has existed without voices. Musical instruments can produce emotions and sounds which are beyond the reach of human vocal chords: from delicate Japanese zen music to the ancient Jewish klezmer tradition, and from the ingoma drums of Burundi, German military bands or the volcanic samba schools of Brazil to the delicate sophistication of Achille-Claude Debussy’s dissonant “Préludes”, the wild cacophony of flautists from Joujouka in Morocco or the magma stirred by Jimi Hendrix’s sublime improvisations — which reached the heart of the reactor on “Drivin’ South”, “Star Spangled Banner” or “Villanova Junction” — myriad forms of instrumental music in all their diversity have been ringing in human ears for millennia.

Instrumental Rock

Rock has always had an instrumental side, and the tendency became a fashion at the end of the Fifties under the influence of essential guitarists like Sol Hoopii, T-Bone Walker, Charlie Christian, Arthur Smith, Chet Atkins, Earl Hooker and Billy Butler with organist Bill Doggett, followed by bands devoted entirely to instrumental rock such as the groups led by Link Wray, Duane Eddy or Dick Dale and The Ventures. Instrumentals became a separate style with groups that didn’t have a singer, like Johnny and the Hurricanes or the British Shadows. Many vocals-oriented combos turned it into a mandatory exercise, like The Rolling Stones (“Stoned” or “2120 South Michigan Avenue” in 1964), The Beatles’ (“Flying” in 1967) or Ten Years After (“Woodchopper’s Ball” in 1967) before it lost momentum in the late Sixties. This anthology traces the different steps in the evolution of instrumental rock from its jazz and country beginnings to rock, in which electric guitars play a central role.

Origins

When jazz became popular in North America in the 1930s, it conquered a mass audience with instrumental pieces featuring improvisations that made listeners get up and dance, i.e. the Swing Era. This conceptual link with dancing, which wasn’t exclusive to African-American music, is inseparable from the notion of “rock”, a music form fundamentally derived from jazz (and from its 1940s “jump blues” incarnation in particular).

While improvisation exists in many music forms all over the world, the attention drawn to artists and musicians taking solos is a characteristic of jazz and many African-American and Caribbean, indeed African styles. This instrumental richness has roots deep in African traditions and the oppression of African-Americans. Negro spirituals or slave-songs were originally expressions of the experiences, strengths and hopes of millions of Africans deported to the Americas and reduced to slavery.2 In various forms of trance — the quest for ancestral ties in many West African animistic religions (notably among Akan, Yoruba & Bantu ethnic groups) — rhythmical music induced a spiritual ecstasy that favoured the improvisation of mysterious vocal messages inspired by spirits.3 Broadly speaking, once slavery was abolished in 1865, these inspired improvisations where the performer’s contribution was decisive merged together inside popular music and were formulated by musical instruments (initially piano, organ, trumpet and saxophone etc.), giving birth to jazz. The Charleston dance craze in the Twenties was just one of its manifestations. Inciting audiences to take part in the collective excitement, free dancing, and expressions of “body and soul” united and released by rhythm, jazz music was often vocal, but there are thousands of magnificent recordings in existence to testify to the musical peaks achieved by instrumentals.

Instrumental Jazz

The origins of “instrumental rock” are to be sought in jazz, the improvised instrumental music form par excellence.4 During World War II the dancing “swing” craze was already an anticipation of rock. One of those jazz forms was boogie-woogie, whose rhythms are particularly irresistible,5 and which evidently lie at the roots of rock. A striking example here is the Boogie Woogie Stomp by pianist Albert Ammons, whose 1936 swing or “groove” strangely recalls recordings made thirty years later by The Rolling Stones, such as “Now I’ve Got a Witness” (1964) or “Andrew’s Blues”. After the “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall (in which Ammons took part in 1938), the boogie woogie style became very popular in the pre-war jazz era they called “Swing”, and it continued during the war. Carried by the rhythm, its creators were capable of recording highly sophisticated arrangements (conceived by musicians such as Duke Ellington) and contained flashes of genius where improvisation lent moments of grace, euphoria and freedom to otherwise “anonymous” musicians who suddenly found themselves in the limelight, backed by a whole orchestra.6

Swing and boogie woogie would soon evolve into the jump blues style, which was the original form of rock. The swing fashion would also give sustenance to orchestras which were very popular with white audiences, bands led by Glenn Miller for example, who hardly ever employed black musicians — it was difficult for them to do otherwise, due to prejudice and the segregation laws — and only rarely included improvisations in their recordings, even though they assimilated the concepts of Afro-American composers. Their love of jazz was sincere, and their recordings were definitely valid, but history has often remembered them for the “commercial” aspects of the dance-music they played in that period.

Some jazz musicians turned to the electric guitar. Based in Paris, the extraordinary manouche gypsy Django Reinhardt was evidently the guitarist who dominated the pre-war period with his Selmer-Maccaferri acoustic guitar and his influence over every guitarist in the world at that time was immense. His lesser-known “electric period” at the end of his life (1953) added another stone to the edifice represented by the repertoire of famous tunes played on the electric guitar. Instrumental rock, the next logical step, would take flight shortly after this very “jazz” period. The influence of T-Bone Walker7 and Charlie Christian8 during World War II no doubt contributed the most to making the electric guitar popular, and the instrument invited itself to be the guest of popular music as early as the Forties. The influence of virtuoso jazz-guitarist Les Paul was also decisive after he became a TV star late in the early 1950s, playing pop songs that featured the many innovations he brought to the instrument. Jazzmen playing famous themes on electric guitars were the heralds of “instrumental rock”: Les Paul (Caravan) and Django Reinhardt (Nuages) are two choice examples.

Country Music

Instrumentalists from even more distant horizons were also raised on boogie woogie and swing jazz, like the Hawaiian Sol Hoopii, a major influence on the steel guitar style which came to the forefront in country music, western swing (cf. Bob Wills here) and country boogie (viz. Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant), and even in the slow number Sleep Walk from Santo & Johnny in 1959. As a great improviser on a quite different instrument, Hoopii was doubtless the most brilliant of those who caused America to discover the culture of Hawaii, and he had many U.S. hits from 1925 onwards. Sol first recorded using a non-electric “lap steel” metal guitar (laid flat on his lap). His highly original title An Orange Grove in California (1934) opens this set. Sol Hoopii was one of the first to convert to an electric lap steel guitar (in 1935), a revolutionary instrument which gave birth to the electric guitar as we know it (cf. Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962, FA 5421, in this collection). Kohala March much influenced the steel guitarists who followed him in country music.9 As early as the Thirties, popular dance hall artists like Milton Brown & his Musical Brownies or Bob Wills & his Texas Playboys also adopted the lap steel and the highly danceable swing music they heard in jazz.10 Their Texan style — western swing — was different from the usual country music around because it had so much energy that it made people get up and dance; it, too, was one of the roots of rock, as you can hear (loud and clear) from these pieces. Western swing titles like Bob Wills’ Boogie and Crazy Rhythm would inspire several country artists who turned to “swing” styles like boogie woogie. The “hillbilly boogie” or “country boogie” style resulting from these influences is the subject of a separate anthology in this collection.11 One great country boogie classic is of course the famous Guitar Boogie by Arthur Smith and his Cracker-Jacks, of which two versions exist; the better-known of the two is the second one, which went to N°9 in the country charts in 1948 and appears here. Born into a family of musicians from South Carolina (he later settled in North Carolina some 250 miles from Nashville), Arthur Smith helped build the sound of country music after the war and Guitar Boogie Shuffle, a cover version of his great hit by The Virtues (alias The Virtuoso Trio) a decade later is also included here and was a best-seller, too. Although they were unrelated, several instrumental rhythm and blues tunes had the same title, notably Guitar Boogie by Henry Crafton in 1949, and a Chuck Berry recording made in 1957.

The post-war Nashville country sound was dominated by guitar giant Chet Atkins, who was raised in poverty and sought to change his life by working on his instrument like there was no tomorrow. Here you can listen to his brilliant work on Canned Heat (an acoustic version) and six years later with his electric Gretsch guitar on the excellent Oh by Jingo! Atkins was a virtuoso and developed his difficult finger-picking style — four fingers — based on the way Merle Travis played (using just his thumb and index finger). Travis was another country music giant, and he was raised in Kentucky to the north. His major inspiration was ragtime-guitar master Blind Blake, and the influence of these three on the roots of rock is incalculable. Merle and Chet would leave their mark on Scotty Moore (who played with Elvis Presley12) and indeed on the whole of the hugely influential rockabilly movement13 — and with it all the rock that followed, from The Beatles to Jeff Beck, Creedence Clearwater and The Stray Cats. Here you can appreciate the influence and quality of their remarkable recordings with the Carol Dills record (obscure but no less estimable), The Rocking Guitar, which was the B-side of a 1956 rockabilly record from Cecil Campbell.

Blues & Rock n’ Roll

If there’s no argument over the importance, influence or talent of country musicians such as Arthur Smith, Merle Travis, Chet Atkins or Jimmy Bryant, the multiplication of great quality instrumentals in jazz, blues and rhythm and blues displayed an unsurpassable richness as eminent expressions of an Afro-American culture that leaned towards musical showmanship. In rock as in other fields in music, the contribution of the African American minority was matchless. In the post-war years it was common for a recording-session to close with an instrumental take, often improvised over a 12-bar blues chord progression. This extra title recorded at the session could later serve as the B-side of a single (and in some cases the A-side). This is perhaps how Guitar Boogie by Henry Crafton or the Big Three Stomp by the Big Three Trio (one of Willie Dixon’s first groups) came into being. Well before Elvis Presley’s first hits, rock was already in fashion by 1950, as Tiny Grimes reminds us with his splendid Rockin’ the Blues Away. Tiny Grimes and his four-string electric guitar appeared on records with the greatest jazzmen, from Charlie Parker to Art Tatum, but in parallel Tiny also led his own group the Rocking Highlanders, and often recorded in this style around 1950. In reality, “Jazz” was just a general-usage term covering a number of different styles, beginning with rock itself in its seminal form: the “jump blues” of the post-war era. Brass instruments were still omnipresent, as you can hear in recordings from the guitarists T-Bone Walker, Harry Crafton, Tiny Grimes, Lowell Fulson or B. B. King, who excels here on Boogie Rock and Mashed Potato Twist. Even so, the presence of an electric guitar wasn’t indispensable in establishing a link with “rock” per se, as testified here on records from pianists Albert Ammons (as early as 1936), Professor Longhair, Bo Diddley with Otis Spann (Travelin’ West) or B. Bumble and the Stingers. On the tracks Last Night and Green Onions, the electric organ, rather than the piano, is the dominant instrument.

Nonetheless, after a few other gems in a bluesy vein such as Guitar Shuffle from Lowell Fulson, it was in Chicago that Earl Hooker recorded his big hit The Hucklebuck. In 1953 this tune opened wide the door for rock instrumentals, contributing to place the electric guitar on a pedestal; it would remain there for some thirty years, until the triumph of keyboards, sampling and other digital instruments. Instrumental rock spread through American and Jamaican popular music in the course of the 1950s,14 and rock history essentially wrote itself around the rise of the electric guitar. In the Fifties it came to the fore with new sounds, and Afro-American rock made its presence felt in different directions as varied as they were inventive. Improvisations on the electric guitar became an almost-compulsory exercise for blues soloists — and for country guitarists also. One of the most astonishing pieces in this set is Space Guitar by Johnny “Guitar” Watson, the future funk star, who uses sound-effects on this title in a radical, innovative manner; it’s hard to believe that this tour de force was cut in February 1954, months before Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley made their studio debuts. Other gems sprang up, like Spinnin’ Rock Boogie by Mickey Baker, the guitarist who recorded with Ray Charles as well as on many other Atlantic sessions and more: like Les Paul before him, Mickey Baker had a television “act” — the “Mickey & Sylvia” duo — where the guitar was prominently featured. As for the guitarist Lafayette Thomas (The Thing), he recorded from 1948 and throughout the Fifties with Jimmy McCracklin’s Blues Blasters — who, apart from their musical merits, inspired the name of the Jamaican group Clue J and his Blues Blasters, here represented by a contribution from guitar-player Ernest Ranglin, a Jamaican studio ace. Other instrumentals of this type (with or without Ranglin) appear in several sets devoted to the music of Jamaica in this series.15 The welcome given by the general public — meaning white audiences — to Honky Tonk by organist Bill Doggett (on which the little-known Billy Butler brilliantly plays guitar) made instrumental recordings increasingly unavoidable. And so other artists playing what Chuck Berry called boogie woogie — Berry preferred that more musicolo-gical term to hackneyed labels like “rock” or “rhythm and blues” — began recording titles with no vocals, including Chuck himself. The Master cut the exquisite In-Go and Guitar Boogie (the Yardbirds with Jeff Beck later recorded an unforgettable version of the latter). The prolific Bo Diddley lined up one instrumental tour de force after another: listen to his irresistible, highly original pieces Mumblin’ Guitar, Travelin’ West, Quick Draw, Give Me a Break or Diddling. Other Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley instrumentals (they also did a whole instrumental album together in 1964 called Two Great Guitars) appear in the triple albums devoted to them on the Frémeaux label.16 Storm Warning (with Dr. John on guitar) and Guybo by Eddie Cochran obviously show huge Bo Diddley influences. More African-Americans coming from blues backgrounds recorded hit instrumentals, among them B. B. King, Freddie King and Albert Collins, all three of whom had an influence on Jimi Hendrix — as did Johnny “Guitar” Watson. If you listen to the 1967 instrumental “Drivin’ South” by the mega-influential Hendrix, who was just twenty in 1962, you can clearly hear the influence of Frosty and “Tremble” by Albert Collins,17 both of which date from the early Sixties.

Soul & Funk

Instrumental rock also contributed to help soul music grow, and by extension the funk created in the Sixties by James Brown, The Meters and a few others. Last Night was a dance-floor hit, and the first one written and played by the young musicians known as the Mar-Keys, who later did much to develop soul music: with the addition of Booker T. Jones in 1962 they became Booker T. and the MG’s, the “house” band of the best soul stable in the southern USA, Stax Records. With the efficient Steve Cropper on guitar, Al Jackson on drums and Duck Dunn on bass, organist Booker T. was just 17 when he recorded their great classic Green Onions. Billy Butler played guitar with saxophonist King Curtis, who also became a great soul figure: his band is featured on many masterpieces recorded for Atlantic and, like Booker T. and the MG’s, Curtis also had a number of instrumental hits including the groovy Soul Twist. As for Preston Epps, his Bongo Rock was produced by Art Laboe, the DJ who invented the compilation-album; this piece was picked up as “Bongo Rock ‘73” by The Incredible Bongo Band, who turned it into a hip hop classic sampled by dozens of artists, among them the Jamaican Kool DJ Herc, who founded the hip hop genre. Even though soul music was derived from gospel — which was basically a vocal style — note also that the bizarre rhythms of Bo Diddley, which you can taste here on Travelin’ West or Diddling, helped shaping new soul rhythm-sections.

Film music

Ragtime, boogie woogie and stride piano styles were very popular between the wars and significantly took part in the rise of the film industry. As early as the Twenties, jazz pianists or small-groups were hired by the producers of silent films to play on film-sets; their job was to create the ambience required by the director — drama or comedy — and play music that would set a tempo for each scene. This practice quickly spread to cinemas/theatres where these films were projected, so that audiences might also capture the same atmosphere: and silent films became associated with these jazz piano styles, which lent a lively note to a night at the movies. The principle then developed into “background music” recorded to be played in cinemas (together with the theme used over the film’s credits) during projections. As from 1945 publishers had started building sound libraries of music that could be hired (or purchased outright) for use as film soundtracks, which enabled their customers to avoid the whole complicated music production process. Records of this type appeared as “mood music”, and when microgroove LPs appeared in the 1950s, “ambient music” was a concept developed in America by conductor Paul Weston (Music For Dreaming, Music For the Fireside), followed by Jackie Gleason (Music for Lovers Only), and in England by Ray Martin, Mantovani and many others. This smooth background music called for a sophistication which sometimes led to excess, with arrangements for violins reaching high levels of bad taste and boredom (cf. brands like “Musak” and “Reditune”). Jazz and rock were (much) more dynamic, and were sometimes used as an alternative to these outdated musical stereotypes, especially if a film was aimed at young people… Rock logically came to musically illustrate many films and television series, and instrumental rock was particularly suitable; take Because They’re Young (Paul Wendkos, 1960) with Duane Eddy: an excerpt from the film soundtrack, this eponymous title was his greatest hit and tied Duane’s career to film music. During this period, instrumental rock gained increasing importance in full-length feature-films with young heroes; it would remain a musical code for the pivotal Fifties/Sixties years, as illustrated by Miserlou by Dick Dale and the Del-Tones, which Quentin Tarantino later used in Pulp Fiction (1994), or Nut Rocker by B. Bumble and the Stingers in Raja Gosnell’s Big Momma’s House (2000).

In the Sixties, the clear, clean sounding guitar style with reverb you could hear from Duane Eddy (playing a Gretsch 6120), The Ventures (Mosrite guitars), Dick Dale (Fender Stratocaster) or The Shadows (Fender Stratocaster) would put a stamp on several film classics’ musical arrangements, such as John Barry’s famous “James Bond Theme” (1962) or Ennio Morricone’s “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly” (1966).

The Far West

As seen above, country music was tremendously influenced by the music of Hawaii (and by Sol Hoopii in particular); fashionable in the Twenties and Thirties, it preceded and then accelerated the invention of the electric lap steel guitar and then the pedal steel. One should also remember that surfing was born in Hawaii, where people had been assiduously playing guitars since the 19th century. In parallel with this, electric guitars with their clear, undistorted sound obtained using a single coil pick up — from Fender, Teisco, Mosrite, Danelectro — was inherited from country music, notably Arthur Smith (here with an acoustic model), Merle Travis (playing a Gibson Super 400), Joe Maphis (a double-neck Mosrite), as well as Jimmy Bryant, Grady Martin and Chet Atkins (with Gretsch guitars, with the “Chet Atkins” model 6120 coming onto the market in 1955). All of them used the clear-cut type of sound also found in rockabilly18, which contrasted with the “dirty sound” distortion present in the work of most bluesmen, from Johnny “Guitar” Watson to Mickey Baker, B. B. King or Albert Collins. With Raunchy in 1957, Bill Justis was no doubt the first to successfully recall the “far west” atmosphere with a country-rock instrumental. Let’s not forget that George Harrison was hired as a Beatle after he played “Raunchy” to John Lennon… Far-west references here include the famous Tequila by The Champs, the titles Quick Draw and Travelin’ West by Bo Diddley, the title Wheels by the String a Longs, Let’s Go (Pony) by the Routers and (Ghost) Riders in the Sky by The Ramrods (phantom horsemen…), and obviously The Shadows with Apache.

Surf rock

When the rock music wave finally washed over a mass white audience in the wake of Elvis Presley’s phenomenal success in 1956-1957, it was given a “bad boy” connotation which caused some musicians serious problems. Despite that, however, its popularity logically gave rise to another, instrumental rock wave, initially embodied by the seductive Duane Eddy, whose first hit (in 1958) was quite aptly entitled Rebel Rouser. Shortly after that, his adaptation of the main theme from the TV crime-series Peter Gunn added to his surface image as a rebel. The original style and sound of Duane Eddy was derived from country guitar and “far west” hits, which preceded the “surf rock” craze. If Eddy was its “pioneer”, in a manner of speaking, Link Wray was an outsider. He was a Shawnee Indian, and he’d had one lung removed due to tuberculosis, so Wray couldn’t sing. But his astonishing tune Rumble (American slang for a street-fight), shook the world of rock ‘n’ roll and sold thousands of copies. Its success was totally unexpected, because the menace in the tune cut across the grain of the entire record-industry: in 1958, everyone in the business was trying to give rock a more reassuring image… Link Wray, the influential inventor of the “power chord”, instantly attracted the young Pete Townshend, the future leader of The Who, who decided there and then to learn to play the electric guitar. Wray, a guitarist whose raw style was decisive and far from any “surf rock” stereotype, is represented here by no fewer than three titles.

Like Bill Haley19, Eddie Cochran was one of the first white rockers to tackle the instrumental genre, and he also played a Gretsch 6120, the favourite guitar of Brian Setzer who in 2011 cut a remarkable guitar-rock album (nothing but instrumentals) which bore the Fifties’ stamp. Cochran was Setzer’s youth hero, and three of Cochran’s titles appear here. Strollin’ Guitar is characteristic of his “surf” sound in that period, while Chicken Shot Blues is a jam session bringing out a very aggressive guitar-style which is perhaps reminiscent of the way Jimmy Page would play with Led Zeppelin a decade later. The rock-instrumental/surf-rock analogy was only really sealed when Dick Dale and his Del-Tones scored a hit with Miserlou in 1962. Marked by the music of the Middle East (Dale had Lebanese origins), but with the addition of a Mexican trumpet, “Miserlou” is based on a traditional Oriental melody with a rock arrangement (on the same principle as the two titles by B. Bumble and the Stingers adapted from classical pieces as was, ten years later, the music produced with such brio by the Dutch group Ekseption). In the summer of 1961 Dick Dale’s concerts were SRO at the Rendezvous Ballroom on Balboa Beach south of L.A., right next to the “spot” called The Wedge, the local surfers’ Mecca. Dale was a surfer, and the sleeve of his first album Surfer’s Choice featured a photo of him in action. Other groups like the Bel-Airs (“Mr. Moto”, 1961), Challengers (the 1962 album Surfbeat) and Surfaris (“Wipeout” in 1963), or again Eddie and the Showmen, took part in the original “surf rock” fashion in southern California. The Chantays hailed from Santa Ana near Balboa, and their gigantic Pipe Line hit (legend has it that they made the record in the back-room of a surf store) was an explicit reference to the “pipelines” formed by the kind of wave only the bravest surfers can ride. But all of these bands, Dick Dale included, owed their guitar-sound (clear with reverb) to the most important instrumental-rock group of the whole period, the legendary Ventures. With Walk Don’t Run (1960), “Perfidia”, “Driving Guitars”, Bulldog and Lullaby of the Leaves, the Ventures were the first to impose that original rock formula consisting of rock arrangements of familiar tunes coming from all horizons. Initially sung by Ina Hayward, “Lullaby of the Leaves” is taken from a Broadway revue (it was anything but a hit) obscurely called Chamberlain’s Brown Scrap Book (1932). It was played on radio by Freddie Berrens’ orchestra and recorded by Ben Selvin and Connie Boswell before becoming a jazz “standard”. The Ventures came from Tacoma, near Seattle, and they also recorded (with great talent) their own versions of the most popular rock instrumentals, including many of the titles in this set. With dozens of albums in their discography and amazing success — plus a reputation for being indestructible — The Ventures remain the greatest instrumental-rock group in history.

In Britain their sound was copied by The Shadows, joining Dick Dale, The Chantays, Routers and many more (including The Beach Boys, a vocal group who also featured this special “surf guitar” sound) and no matter where the studio was located, a number of other groups were influenced by Bob Bogle and Nokie Edwards’ Ventures: in Stockholm, with the Spotnicks’ “Orange Blossom Special” (1961), the Trashmen in Minneapolis (“Malaguena”, 1964), the Flying Padovanis in London (“Western Pasta”, 1981) and, of course, the first studio recording made by The Beatles, in Hamburg in 1961, was “Cry for a Shadow”, released in 1964.

Bruno Blum

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Denis “Glutzenbaum” Bouillet, Yves Calvez, Stéphane Colin, Gilles Conte, Bo Diddley, Henry Padovani, Vincent Palmer, Jérôme Piel d’Arc, Gilles Pétard, Brian Setzer and Michel Tourte.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Bruno Blum’s Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz Blues R&B Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) and Gérard Herzaft’s Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007) contain vocal pieces but also instrumentals by Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, Chuck Berry, Bob Wills, Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant, Floyd Smith, Alvino Rey et al (cf. fremeaux.com), and Jean Buzelin’s three-album series Boogie Woogie Piano (FA036, FA5164, FA5226) also has thematic ties with this Rock Instrumentals set.

2. Cf. Slavery in America (FA5467).

3. Listen to Jamaica Folk, Trance Possession 1939-1961 (FA5384), especially the title “Pukkumina Cymbal”.

4. Cf. The Best Small Jazz Bands 1936-1955 (FA5194).

5. Cf. all three volumes of Boogie Woogie Piano (FA036/FA5164/FA5226).

6. Cf. The Greatest Black Big Bands 1930-1956 (FA5287).

7. Cf. T-Bone Walker – The Blues – Father of the Modern Blues Guitar 1929-1950 (FA 267).

8. Cf. Charlie Christian - The Quintessence 1939-1941 (FA218).

9. Listen to Sol Hoopii in Electric Guitar Story (FA5421), Hawaiian Music Honolulu-Hollywood-Nashville 1927-1944 (FA035) and Rock n’ Roll Vol. 1 - 1927-1938 (FA351).

10. Milton Brown and Bob Wills feature in Western Swing 1928-1944 (FA032).

11. Cf. Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160).

12. Elvis Presley face à la l’histoire de la musique américaine 1954-1956 (FA5361) contains original versions alongside Presley’s own recordings of them to show his influences.

13. Cf. Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5426).

14. Cf. Jamaica Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA5358) and Roots of Ska - Rhythm and Blues Shuffle USA & Jamaica 1942-1962 which contain several instrumentals.

15. Cf. Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues 1956-1961 (FA5358), USA-Jamaica Roots of Ska — Rhythm and Blues Shuffle 1942-1962 (FA5396) and Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA5358).

16. Cf. The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409), The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) and 1959-1962 (FA5406).

17. Albert Collins’ “Tremble” is included in Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz Blues R&B Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421).

18. Cf. Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

19. Cf. The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1962 (futur release).

Discography - ROCK INSTRUMENTALS - CD 1 1934-1956

1. An Orange Grove in california - Sol Hoopii

(Israel Isidore Berlin aka Irving Berlin)

Sol Ho’opi’i-National Hawaiian lap steel acoustic guitar; unknown bj, b. Possibly Los Angeles. 1934.

2. Boogie Woogie Stomp - Albert Ammons and his Rhythm Kings

(Clarence Smith aka Pinetop Smith, arranged by Albert Ammons)

Guy Kelly-tp; Dalbert Bright-cl, as; Albert Ammons-p; Ike Perkins-g; Israel Crosby-b; Jimmy Hoskins-d. Chicago, February 13, 1936.

3. Bob Will’s Boogie - Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys

(James Robert Wills aka Bob Wills, Millard Kelso, Lester Barnard, Jr. aka Junior Barnard)

James Robert Wills aka Bob Wills-fiddle, v; Lester Barnard, Jr. aka Junior Barnard-electric g; Tiny Moore-electric mandolin; Herb Remington-steel g; Jimy Widener-bj; Joe Holley-fiddle; Millard Kelso-p; Billy Jack Wills-b; Johnny Cuviello-d. Hollywood, September 4, 1946.

4. Caravan - Les Paul

(Edward Kennedy Ellington as Duke Ellington, Juan Tizol)

Lester William Polsfuss as Les Paul-lead g; Paul Smith, p; Bob Meyer-b; Tommy Rinaldo-d. New York City, January 9, 1947.

5. Crazy Rhythm - Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys

(Lee Julian Pockriss)

James Robert Wills aka Bob Wills-fiddle, v; Eldon Shamblin-electric g; Tiny Moore-electric mandolin; Herb Remington-steel g; Ocie Stockard-bj; Millard Kelso-p; Billy Jack Wills-b; Johnny Cuviello-d. Sound Recorders, San Francisco, September 6, 1947.

6. Canned Heat - Chet Atkins

(Chester Burton Atkins as Chet Atkins)

Chester Burton Atkins as Chet Atkins-g; George Barnes-g; Harold Siegel-b; Charles Hurta-fiddle; Augie Klein-accordion. RCA Studios, Chicago, August 8, 1947.

7. Guitar Boogie - Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith with his Cracker-Jacks

(Arthur Smith)

Arthur Smith-lead g; possibly Don Reno-g: unknown b. 1948. MGM 10293, released in December, 1948.

Note: another version of this composition was recorded by Arthur Smith earlier and is not included in this set.

8. Guitar Boogie - Harry Crafton and the Jivetones

(Harry Crafton)

Harry Crafton-g; possibly Joe Sewell-ts; unknown b, d. Philadelphia, 1949.

9. Cannonball Stomp - Merle Travis

(Merle Travis)

Merle Travis-g. Capitol Recording Studio, 5515 Melrose Ave., Hollywood, July 7, 1949.

10. The Big Three Stomp - The Big Three Trio

(Leonard Caston, Ollie Crawford, William James Dixon aka Willie Dixon)

Ollie Crawford-g; Leonard Caston-p; William James Dixon as Willie Dixon-b; Hillard Brown-d. Chicago, February 18, 1949.

11. Strollin’ With Bones - T-Bone Walker and his Band

(Aaron Thibeaux Walker as T-Bone Walker, Eddie Davis, Jr. aka Lockjaw Davis)

Eddie Hutcherson-tp; Edward Hale-as; Eddie Davis, Jr. aka Lockjaw Davis-ts; Zell Kindred-p; Buddy Woodson-b; Snake Simms-d. Los Angeles, April 5, 1950.

12. Longhair Stomp - Roy Byrd and his Blues Jumpers

(Henry Roeland Byrd aka Roy Byrd, Professor Longhair, Fess)

Henry Roeland Byrd aka Roy Byrd, Professor Longhair, Fess-p; possibly Lester Alexis aka Duke-d. New Orleans, July, 1950.

13. Rockin’ The Blues Away - Tiny Grimes Quintet

(Lloyd Grimes as Tiny Grimes)

Lloyd Grimes as Tiny Grimes-tenor g; Wilbert Prysock aka Red Prysock-ts; Freddie Redd-p; unknown b; possibly Jerry Potter-d. Chicago, November 27, 1951.

14. Kohala March - Sol Hoopii

(traditional)

Sol Ho’opi’i- electric lap steel g; unknown-g, b. Possibly Los Angeles. 1951.

15. Guitar Shuffle - Lowell Fulson

(Lowell Fulson)

Lowell Fulson- g; Earl Brown-as; Lloyd Glenn-p; Billy Hadnottt-b; Bob Harvey-d. Swing Time 295. Los Angeles, ca. October, 1951.

16. Midnight Ramble - Speedy West & Jimmy Bryant

(Ruby Rakes, Wesley Webb West as Speedy West)

Ivy J. Bryant, Jr. as Jimmy Bryant-lead g; Wesley Webb West as Speedy West-pedal steel g; Billy Strange-g; Billy Liebert-p; Cliffie Stone-b; Roy Harte-d. Hollywood, May 6, 1952.

17. Nuages - Django Reinhardt

(Jean Reinhardt aka Django Reinhardt)

Jean Reinhardt as Django Reinhardt-electric g; Maurice Vander-p; Pierre Michelot-b; Jean-Louis Viale-d. Paris, March 10, 1953.

18. Oh by Jingo! - Chet Atkins

(Albert Von Tilzer, Lew Brown)

Chester Burton Atkins as Chet Atkins-g; Thomas Grady Martin-g; Jerry Byrd-steel g; Charles Grean-b; Phil Kraus-d. Produced by Stephen Sholes. RCA Victor Studio 1, 155 East 24th St., Manhattan, New York City, March 18, 1953.

19. The Hucklebuck - Earl Hooker

(Andy Gibson, Roy Alfred)

Earl Zebedde Hooker as Earl Hooker-g; Clarence Perkins as Pinetop Perkins-p; unknown b; possibly Willie Nix-d. Memphis, July 15, 1953.

Note: “The Hucklebuck” is based on the melody of Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time”.

20. Space Guitar - Young John Watson

(John Watson, Jr. aka Johnny “Guitar” Watson)

John Watson, Jr. as Johnny “Guitar” Watson-v, g; Bill Gaither-ts; Devonia Williams-p; Mario Delagarde-b; Charles Pendergraph-d. Federal 12175. Los Angeles, February 1, 1954.

21. Walking the Strings - Merle Travis

(Merle Travis)

Merle Travis-g. Capitol Recording Studio, Hollywood, December 28, 1954.

22. The Thing - Lafayette Thomas

(Jerry Thomas aka Jeri, Lafayette Thomas)

Jerry Thomas aka Jeri, Lafayette Thomas-g;

Al Prince Orchestra: unknown ts, bs, p, b, d. Trilyte 1100. Oakland, circa 1955.

Discography - ROCK INSTRUMENTALS - CD 2 : 1955 - 1959

1. Boogie Rock - B.B. King

(Riley Ben King aka B.B. King, Joseph Bihari as Joe Josea)

Riley Ben King as B.B. King-v, g; Johnny Board-ts; Maxwell Davis, sax; unknown saxes, tp, b; Willard McDaniel-p; Ted Curry or Jesse Sailes-d. Los Angeles, 1955.

2. Honky Tonk - Bill Doggett

(Henry Glover, Billy Butler, William Ballard Doggett as Bill Doggett, Clifford Scott, Berisford Shepherd aka Shep Shepherd)

William Ballard Doggett as Bill Doggett-org; Billy Butler-g; Clifford Scott-ts; Berisford Shepherd as Shep Shepherd-d. Cincinnati, 1956.

3. Spinnin’ Rock Boogie - Mickey Baker

(Gibson, Bill Hendricks, Francis)

Mc Houston Baker as Mickey Baker-g; Bill Hendricks and his Orchestra: unknown p, b, d. Produced by James Vienneau aka Jim Vienneau. Coastal Studio, New York City, December 19, 1956.

4. The Rocking Guitar - Cecil Campbell (feat. Caroll Dills)

(Caroll Dills, Cecil Campbell)

Cecil Campbell-g; Caroll Dills-lead g; unknown b, d. Charlotte, North Carolina, April, 1957.

5. Raunchy - Bill Justis

(Willian Everett Justis aka Bill Justis)

Sidney Manker-g; Roland Janes-g; Willian Everett Justis as Bill Justis-ts; Jimmy Wilson-p; Sid Lapworth-b; James van Eaton-d. Sun Studio, 706 Union Avenue, Memphis, June 5, 1957.

6. Rumble - Link Wray and his Raymen

(Fred Lincoln Wray aka Link Wray)

Fred Lincoln Wray as Link Wray-g; Shorty Horton-b; Douglas Wray as Doug Wray-d. Produced by Milton Grant aka Milt Grant. Washington D.C., 1957.

7. Tequila - The Champs

(Danny Flores aka Chuck Rio)

Dave Burgess- electric g; Danny Flores as Chuck Rio-ts, v; Buddy Bruce-g; Cliff Hils aka Clifford Hils-b; Eugene Alden as Gene Alden-d. Gold Star Studios, Los Angeles, December 1957.

8. In-Go - Chuck Berry

(Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below, d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, December 29 or 30, 1957.

9. Guitar Boogie - Chuck Berry

(Charles Edward Anderson Berry aka Chuck Berry)

Charles Edward Anderson Berry as Chuck Berry-g, v; Lafayette Leake-p; Willie Dixon-b; Fred Below, d. Produced by Lejzor Czyz as Leonard Chess and Fiszel Czyz as Phil Chess, Chicago, December 29 or 30, 1957.

10. Rebel Rouser - Duane Eddy and his “Twangy” Guitar

(Barton Lee Hazlewood aka Lee Hazlewood, Duane Eddy)

Duane Eddy-g; Gil Bernal-ts; Al Casey or Bobby Wheeler-b; Bob Taylor or Mike Bermani-d. The Rivingtons: Carl White, Al Frazier, Turner Wilson, Jr. as Rocky Wilson, John Harris as Sonny Harris-v, handclaps. Produced by Barton Lee Hazlewood as Lee Hazelwood and Lester Sill. Phoenix, Arizona, 1958. Released May 26, 1958.

11. Dixie Doodle - Link Wray and his Raymen

(Fred Lincoln Wray aka Link Wray, Milton Grant aka Milt Grant)