- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

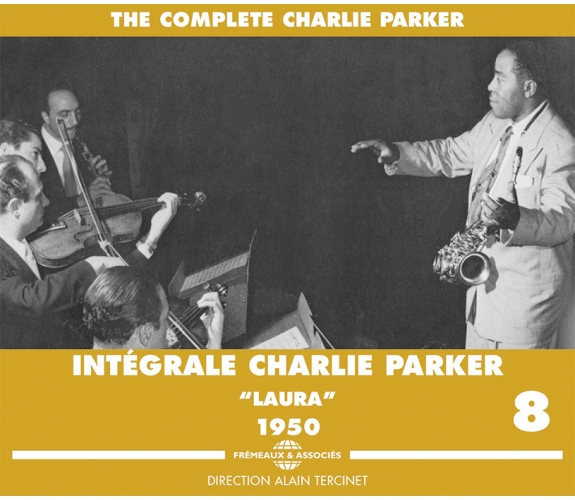

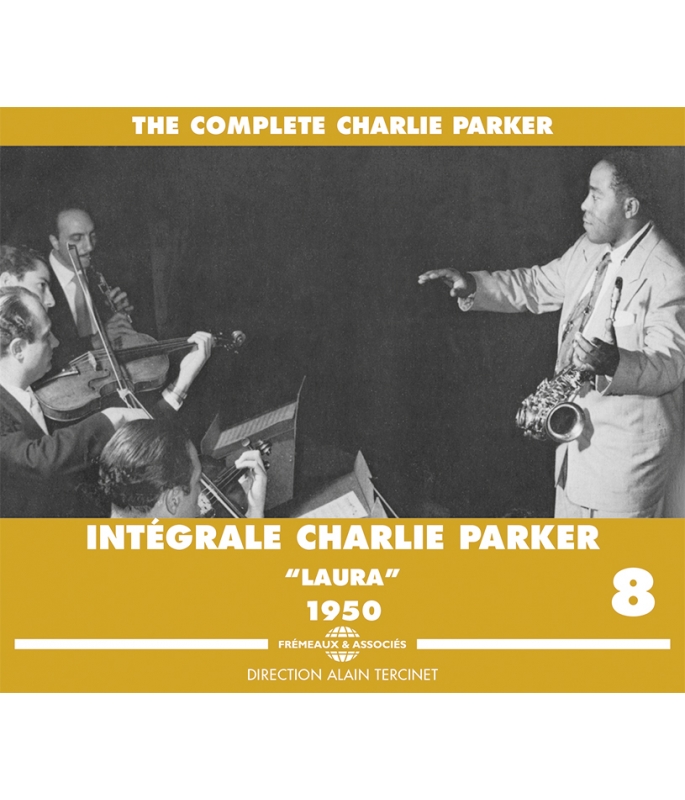

LAURA - 1950

Ref.: FA1338

EAN : 3561302133829

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 16 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

LAURA - 1950

LAURA - 1950

“Melody... If you were being tortured and could only keep one — even if the torture was fierce — then it would have to be Laura. Played by Charlie Parker, Laura steps through the gates of Paradise wreathed in little scrolls of pure, undiluted happiness. Nothing can spoil that moment every time I hear it.” Jean-Pierre MARIELLE (Le grand n’importe quoi, Calmann-Lévy, 2010)

JUST FRIENDS - 1949-1950

“PASSPORT” 1949

GROOVIN' HIGH - 1940-1945

Un livre d'Alain Tercinet - Préface de Pascal...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Star EyesCharlie Parker QuartetG. Depaul00:03:291950

-

2BluesCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:471950

-

3I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker QuartetJ. McHugh00:02:511950

-

4Lament For CongaCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:05:441950

-

5Mambo FortunatoCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:05:131950

-

6BloomdidoCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:261950

-

7An Oscar From TreadwellCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:211950

-

8An Oscar From Treadwell MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:231950

-

9MohawkCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:491950

-

10Mohawk MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:361950

-

11My Melancholy BabyCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:241950

-

12Leap FrogCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:301950

-

13Leap Frog MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:341950

-

14Leap FrogCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:001950

-

15Relaxin' With MeCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:571950

-

16Relaxin' With Me MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:471950

-

17I Can't Get StartedCharlie Parker QuartetI. Gershwin00:04:531950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

152 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:231950

-

2AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:221950

-

3Just FriendsCharlie Parker QuintetS.M. Lewis00:03:051950

-

4AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:131950

-

5April In ParisCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:161950

-

6A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:231950

-

752 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:191950

-

8AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:191950

-

9Just Friends IICharlie Parker QuintetS.M. Lewis00:03:031950

-

10AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:131950

-

11April In Paris IICharlie Parker Quintet00:03:021950

-

12Medley I Bewitched SummertimeCharlie Parker QuintetL. Hart00:05:071950

-

13Medley II I Cover The Waterfront Gone With The WindCharlie Parker QuintetE. Heyman00:04:351950

-

14Easy To Love 52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:011950

-

15Medley III What's New It's The Talk Of The TownCharlie Parker QuintetJ. Burke00:06:451950

-

16Moose The Mooche 52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:10:351950

-

17Lover Come Back To MeCharlie Parker with The Tony Scott QuartetO. Hammerstein II00:17:121950

-

1852 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker with The Tony Scott Quartet00:01:391950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Dancing In The DarkCharlie Parker with StringsH. Dietz00:03:111950

-

2Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker with StringsE. Heyman00:03:071950

-

3LauraCharlie Parker with StringsJ. Mercer00:02:581950

-

4East Of The SunCharlie Parker with StringsB. Bowman00:03:391950

-

5They Can't Take That Away From MeCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:201950

-

6Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with StringsCole Porter00:03:301950

-

7I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker with StringsDorothy Fields00:03:341950

-

8I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker with StringsDorothy Fields00:03:301950

-

9I'll Remember AprilCharlie Parker with StringsP. Johnstone00:03:071950

-

10Annonce répétitionCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:051950

-

11What Is This Thing Called Love DesannonceCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:021950

-

12Annonce Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:081950

-

13RépétitionCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:411950

-

14April In ParisCharlie Parker with StringsE.Y. Harburg00:03:111950

-

15Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:141950

-

16What Is This Thing Called Love DesannonceCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:511950

-

17What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:081950

-

18What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:521950

-

19April In ParisCharlie Parker with StringsE.Y. Harburg00:03:101950

-

20RepetitionCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:461950

-

21Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:231950

-

22RockerCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:001950

Intégrale Charlie parker volume 8

THE COMPLETE Charlie Parker 8

INTÉGRALE Charlie Parker 8

“LAURA”

1950

DIRECTION ALAIN TERCINET

Proposer une véritable «?intégrale?» des enregistrements laissés par Charlie Parker est actuellement impossible et le restera longtemps. Peu de musiciens ont suscité de leur vivant autant de passion. Plus d’un demi-siècle après sa disparition, des inédits sont publiés et d’autres – dûment répertoriés – le seront encore. Bon nombre d’entre eux ne contiennent que les solos de Bird car ils furent enregistrés à des fins privées par des musiciens désireux de disséquer son style. Sur le seul plan du son, ils se situent en majorité à la limite de l’audible voire du supportable. Faut-il rappeler, qu’à l’époque, leurs auteurs employaient des enregistreurs portables sur disque, des magnétophones à fil, à bande (acétate ou papier) et autres machines devenues obsolètes, engendrant des matériaux sonores fragiles??

Aucun solo joué par Charlie Parker n’est certes négligeable, toutefois en réunissant chronologiquement la quasi-intégralité de ce qu’il grava en studio et de ce qui fut diffusé à l’époque sur les ondes, il est possible d’offrir un panorama exhaustif de l’évolution stylistique de l’un des plus grands génies du jazz?; cela dans des conditions d’écoute acceptables.

Toutefois lorsque la nécessité s’en fait sentir stylistiquement parlant, la présence ponctuelle d’enregistrements privés peut s’avérer indispensable. Au mépris de la qualité sonore.

L’intégrale CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOL. 8

“LAURA” 1950

Après les prodigalités indispensables liées à l’orchestre à cordes, Norman Granz décida d’enregistrer Bird accompagné seulement d’une rythmique ; sans interlocuteur. Une séance que, bien à tort, il déclarera décevante et dont, curieusement, aucun des participants ne gardera en mémoire le moindre souvenir. Pourtant, à partir de I’m in the Mood for Love, Parker brode des variations dignes de celles qu’il avait imaginé sur Embraceable You ou Don’t Blame Me. Il sublime Star Eyes, une chanson assez banale illustrée par Jimmy Dorsey au début des années 1940. Et Blues n’est en rien inférieur aux deux autres interprétations.

À cette période Parker fut au centre d’une curieuse aventure. L’arrangeur Gene Roland, à l’origine de la fameuse section des «?Four Brothers?» chez Woody Herman, avait mis sur pied, en studio, une formation de vingt-sept musiciens servant d’écrin aux improvisations de Bird. Y figuraient - parmi d’autres - Red Rodney, Don Joseph, Don Ferrara, Eddie Bert, Jimmy Knepper, Joe Maini, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Don Lanphere. La dimension de l’ensemble fit peur au directeur de l’Adams Theatre de Newark que le comique iconoclaste Lord Buckley avait réussi à circonvenir. Cet ensemble pléthorique ne laissa derrière lui qu’un enregistrement calamiteux, peu convaincant, saisi au cours d’une séance de répétition aux studios Nola. Composé de fragments de morceaux – une seule version de It’s a Wonderful World semble complète -, cette bande laisse parfois deviner plus qu’entendre quelques interventions de Parker et, probablement, de Zoot Sims.

La boulimie musicale dont Bird était atteint le conduisait à se rendre impromptu dans des endroits où on ne l’attendait guère. Témoin son apparition au Renaissance Ballroom où se produisait l’orchestre de Machito. Parfaitement intégrées, les interventions de Parker ne donnent aucunement l’impression de collages. Mambo Fortunato offre l’occasion au pianiste (Rene Hernandez ?) de prendre un excellent solo, alors qu’un trompettiste (Howard McGhee ?) intervient de belle façon sur Lament for Conga (ou Congo suivant les éditions). Quoiqu’il en soit, le résultat est remarquable. Le même jour (ou le lendemain) Bird se serait joint au même orchestre pour un Reminiscing at Twilight. Sans prendre de solo.

À de multiples reprises, Dizzy Gillespie avait souhaité rencontrer de nouveau Parker en studio. Un souhait exaucé à l’expiration de son contrat avec RCA Victor. Contrairement aux conventions du passé, Dizzy ne sera pas le leader en titre de la séance. Réalisée pour le compte du label Clef dirigé par Norman Granz, la direction en reviendra à Charlie Parker. Furent engagés le contrebassiste Curley Russell et, à la batterie, Buddy Rich. Une présence qui fit polémique. Roy Haynes se plaindra d’avoir été évincé par Norman Granz qui s’en défendra comme un beau diable, arguant du fait qu’il n’avait jamais imposé qui que ce soit à quiconque lors d’une séance d’enregistrement. Il croyait, en revanche, se souvenir que c’était Bird lui-même qui avait réclamé l’assistance de Buddy Rich, partie prenante dans ses enregistrements avec cordes et son partenaire au sein du J.A.T.P. Ayant eu l’intelligence de renoncer aux feux d’artifices dont il était coutumier, Buddy Rich tiendra plus qu’honorablement sa place.

Comme pianiste, Bird avait jeté son dévolu sur Thelonious Monk, tombé pratiquement dans l’oubli à cette période - de juillet 1948 à juillet 1951, il ne réalisa pas de séance personnelle. Par contre, aucune de ses compositions ne fut inscrite au programme. À une exception près, toutes seront signées de Parker ; An Oscar From Treadwell, basé une nouvelle fois sur les harmonies de I Got Rhythm, deux blues, Bloomdido et Mohawk, Relaxin’ with Lee extrapolé de Stompin’ at the Savoy. Et Leap Frog qui renouait avec la furia des années de conquête. Au cours des trois versions publiées, l’intensité des 8/8 échangés entre Bird, Diz et Buddy Rich montre à l’envi que le temps n’a pas eu de prise sur leur entente. Il n’empêche. Leap Frog demanda plus de dix prises dont un bon nombre de faux départs... La présence ici de My Melancholy Baby relève purement et simplement de la «?private joke?». Durant un engagement au Three Deuces, Parker et Gillespie avaient été victimes d’un casse-pieds en état d’ébriété qui exigeait à toute force de l’entendre jouer. Cette romance composée en 1912 ayant connu plus tard un certain succès interprétée par Bing Crosby, inspira Monk qui la reprendra d’ailleurs au cours de son ultime séance d’enregistrement. Parker l’agrémente ici d’une coda phagocytant Country Gardens, l’une de ses citations favorites.

«?Bonjour mesdames et messieurs, bienvenue au Downtown Café Society. Nous aimerions vous présenter maintenant pour votre plaisir, la seconde partie de notre spectacle. Elle débutera par un morceau orchestral, celui-là même qui, publié récemment, a été enregistré par votre serviteur accompagné par un orchestre à cordes. Nous espérons que vous l’apprécierez autant sans les cordes. Just Friends…?».

Le 8 juin 1950, commençait l’engagement de Charlie Parker au Downtown Café Society. Un lieu quasiment légendaire de Greenwich Village, ouvert en 1938 par Barney Josephson. Très à gauche, il avait adopté pour slogan l’épithète attribuée à son club par un journaliste du New York American Journal, «?The wrong place for the Right people?». Sa politique était diamétralement à l’opposé de celle du Cotton Club. Rejetant toute ségrégation, Barney Josephson refusait même d’engager des artistes dont il jugeait l’attitude trop «?oncle Tom?». Billie Holiday y avait créé Strange Fruit, la chanson-brûlot d’Abel Meeropol dénonçant le lynchage ; Django Reinhart s’y était produit lors de sa venue aux Etats-Unis et les carrières d’Hazel Scott et de Lena Horne devaient beaucoup au Downtown Café Society .

En 1950, les choses avaient quelque peu changé. Les opinions politiques des deux frères Josephson avaient attiré sur eux les foudres de la Commission des activités anti-américaines dirigée par le sénateur McCarthy. Leon sera même incarcéré, ce qui provoqua l’indignation de Dashiell Hammett qui enverra une lettre de protestation au président Truman. Barney, fatigué, décidera en 1951 de clore les portes d’un Café Society sur le déclin.

Familier de Bird, le batteur Alan Levitt assura que ce dernier n’était guère satisfait d’un engagement le contraignant à jouer pour la danse, ce qui explique d’ailleurs l’importance du bruit de foule audible sur les enregistrements. Il se souvint avoir entendu Kenny Dorham et Roy Haynes lui conseiller de prendre les choses du bon côté, d’autant plus qu’en attraction principale figurait le trio d’Art Tatum que Parker révérait. Une admiration à sens unique. Durant une interprétation de Tea for Two, sortant des coulisses à la fin d’un chorus, Bird pénétra sur scène en jouant. Tatum lui enjoignit de cesser sur le champ…

En raison de l’emploi pour lequel il avait été engagé, le quintette joua des compositions habituellement liées à la formation à cordes, April in Paris, Just Friends, Easy To Love. Seules, une ou deux pièces relevaient de son répertoire habituel, A Night in Tunisia que, curieusement, ainsi qu’il l’avait déjà fait au Birdland avec Fats Navarro, Parker abandonna à Kenny Dorham et Moose the Mooche qui bénéficia de la présence du clarinettiste Tony Scott venu faire le bœuf. Sur les trois medleys conservés, l’un d’eux réunissant What’s New et It ‘s the Talk of the Town est exécuté par Kenny Dorham et Al Haig.

Tony Scott est de retour au cours d’une longue interprétation de Lover Come Back to Me, provenant du Café Society certes mais dont il est impossible de déterminer la date exacte. Dick Hyman : «?Son origine est liée au fait que, en tant que Tony Scott Quartet, nous jouions au Café Society six nuits par semaine. Un engagement renouvelé à de multiples reprises au fil des ans. Parfois le dimanche, tard dans la nuit aux alentours de trois heures du matin, Parker arrivait pour le set final et s’asseyait en notre compagnie. Les autres membres de l’orchestre étaient Irv Kluger à la batterie et Irv Lang à la basse. J’en suis certain, ils furent les membres stables de la formation pendant un bout de temps. Encore que le personnel ait varié (1).?» Interrogé sur l’identité des intervenants au long de Lover Come Back To Me, Dick Hyman reconnut vraisemblable la présence de Mundell Lowe à la guitare et de Brew Moore au ténor ainsi que celle de Leonard Gaskin à la basse. Par ailleurs, il confirma qu’il n’existait rien d’équivalent sur les bandes en sa possession.

L’année 1950 sera cruciale pour Parker. Sur un plan professionnel au premier chef : du fait de son addiction aux drogues dures, Red Rodney fit l’objet de plusieurs arrestations, occasionnant un flottement au sein du quintette. En sus l’orchestre à cordes occupant fort Bird, il prit l’habitude de se déplacer seul. Ce qu’il fera en Suède. Autre changement, dans sa vie privée cette fois. Chan Richardson : «?Mai 1950. Il fallut bien s’incliner devant l’inévitable. On s’installa chez Bird, Kim et moi, 11e Rue Est, pour le meilleur et pour le pire. Il avait enfin une famille qu’il conserverait jusqu’à sa mort (2).?» Dorénavant Parker partageait un appartement avec sa quatrième compagne et la fille de cette dernière.

Durant le mois de juin, Bird se rendit à plusieurs reprises le dimanche aux William Henry Apartments situés 139ème Rue et Broadway. Le saxophoniste alto Joe Maini y avait squatté un sous-sol - assez sordide selon les témoins - où se déroulaient des jam sessions réunissant aussi bien Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Zoot Sims, Warne Marsh que Jimmy Knepper, Herb Geller ou Jon Eardley (3). Il en subsiste quelques fragments enregistrés. Malheureusement, pour économiser la bande magnétique, n’ont été pratiquement retenus que les interventions de Bird. Ce qui se justifie d’un point de vue pédagogique mais, déconnectés de leur environnement, ces extraits perdent quelque peu de leur signification un demi-siècle plus tard.

Pour le compte de Norman Granz, Parker se rendit de nouveau en studio en compagnie d’une formation à cordes. Plus étoffée cette fois puisque réunissant cinq violons, un alto, deux violoncelles, une harpe associés à un cor, un hautbois et une rythmique composée de Ray Brown, Buddy Rich et Bernie Leighton au piano. À cette occasion probablement, Bird interpréta sur les ondes, en la compagnie du seul trio rythmique un I Can’t Get Started magnifique.

D’ici son départ pour la Suède, à la tête de son orchestre à cordes ramené à son instrumentation d’origine, Bird se produisit au Birdland (deux fois), à l’Apollo Theater, au Blue Note de Chicago, au Club Harlem de Philadelphie et fut de nouveau enregistré par Granz à Carnegie Hall au cours d’un concert du Jazz at the Philharmonic, ce qui confirmait son statut de vedette.

«?Je réclamais des cordes depuis 1941?». Certes. Probablement à cette période, Parker avait-il apprécié l’orchestre d’Artie Shaw augmenté d’une section de violons. Un exemple suivi par Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, Harry James et Glenn Miller. Néanmoins, il est difficile d’imaginer à cette époque Parker demandant à Jay McShann d’en faire autant. Au vrai, l’influence d’Artie Shaw fut sans doute déterminante plus tard, lorsqu’il se produisit en 1949 au Bop City à la tête de son Symphony Orchestra après avoir enregistré, avec son New Music String Quartet, deux arrangements d’Alan Shulman, Mood in Question et Rendez-vous for Clarinet and Strings. Des partitions autrement plus audacieuses que celles auxquelles Bird aurait à faire.

La révérence de ce dernier envers la musique «?sérieuse?» n’était un secret pour personne. Au cours du Blindfold Test conduit en 1948 pour le compte de la revue Metronome par Leonard Feather, il avait exprimé son admiration pour Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Ravel, Debussy, Hindemith, Wagner et Bach. Teddy Reig parlera de son intérêt pour le Concertino da Camera pour saxophone et orchestre de Jacques Ibert et, chez Gil Evans, il demandait toujours à entendre le Children’s Corner de Debussy. Le saxophoniste baryton Danny Bank se souviendra l’avoir entendu s’exercer en jouant des passages d’œuvres classiques dans une chambre du Bryant Hotel. Le compositeur, chef d’orchestre et corniste David Amram reconnaîtra que Bird lui avait fait prendre conscience de l’importance de Frederic Delius. Parker parlera aussi de son désir d’étudier avec Stefan Wolpe et Edgar Varese. Pour l’instant, il en était loin, confronté aux arrangements exécutés par sa section de cordes.

Cette fois, Norman Granz s’était adressé à Joe Lippman dont la principale qualité était d’aimer la musique de Parker. Ses partitions suscitèrent chez Bird un enthousiasme quelque peu exagéré en regard de leur vertu première qui était en fait de lui laisser le champ libre. Toutefois, guère convaincu par son travail sur Easy to Love qu’il trouvait trop sirupeux, il commanda une nouvelle partition à Jimmy Mundy qui imagina un interlude assez inattendu dans ce contexte. Elle fut présentée pour la première fois à l’Apollo le 23 août et emporté par l’enthousiasme, Parker attribua carrèment à Jimmy Mundy la paternité de l’œuvre composée en fait par Cole Porter.

La section de cordes se contentant de tenir son rôle d’accompagnement et n’ayant plus vraiment d’interlocuteur, Bird se trouvait, toutes proportions gardées, dans la situation d’un soliste de concerto. Contrainte supplémentaire, n’ayant pas de partition à suivre, il devait improviser. Et improviser sur des standards rebattus comme Laura, Easy to Love ou Out of Nowhere - il n’y aura guère que Repetition de Neal Hefti et Rocker de Gerry Mulligan pour déroger à la règle. Des chansons que, en incomparable mélodiste, Parker s’appropriera sans recourir aux restructurations pratiquées par les boppers.

Autre défi, faire oublier, dans un premier temps, la maigreur du répertoire. Lors de son passage à l’Apollo, un ensemble de six sets fut enregistré. Ils comportent quatre morceaux identiques, d’une durée similaire, repris dans le même ordre, chaque séquence ne dépassant guère les dix minutes (4). Dans pareil carcan, Bird réussissait la gageure de ne pas se recopier en multipliant les variations, parfois infimes, entre les versions. Ainsi, une fois, à l’occasion de What Is This Thing Called Love, au lieu d’exposer la mélodie de Cole Porter, il interprète sa paraphrase due à Tadd Dameron, Hot House. Une rareté malheureusement de piètre qualité sonore.

Interrogé sur ce qu’il éprouvait dans ce contexte, Roy Haynes répondit : «?J’aime les mélodies et beaucoup des morceaux que Charlie Parker jouait avec les cordes étaient des mélodies. Elles pouvaient être un peu empruntées parfois mais je pense que Bird s’efforçait de toucher le public ce qui semblait fonctionner. C’était reposant, vous savez. Je ne crois pas que j’aurais aimé le faire tout le temps chaque soir. Ce n’était pas le cas, il y avait des moments où il laissait tomber les cordes et avec la section rythmique seule, il se laissait aller plutôt que de suivre les arrangements tels qu’ils avaient été écrits (5).?» Ainsi, en septembre 1952, au Rockland Palace, la durée de Rocker se verra doublée. Attendant sagement leur tour de ré-exposer le thème, les cordes restèrent muettes pendant l’envol de Bird.

Partageant l’affiche de l’Apollo avec lui en tant que membre de la formation dirigée par Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan résuma fort justement la situation : «?Pendant une semaine, j’ai joué à l’Apollo au même programme que Charlie. Il était accompagné par un orchestre qui comprenait cette section de cordes d’une bêtise incroyable. Trois violons, un alto, un violoncelle, je crois. Les arrangements à ras du sol constituaient le meilleur repoussoir possible pour Bird. Par la suite, certains lui ont écrit des partitions plus intéressantes mais, du coup, elles ne possédaient pas la même exemplarité. Par leur extrême simplicité, les arrangements d’origine constituaient un bien meilleur cadre pour entendre Bird faire ce qu’il voulait : prendre une de ces foutues mélodies et la transformer en quelque chose qui appartienne au domaine de l’art (6).?»

Alain Tercinet

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Interview de Dick Hyman par Mark Weber, Jazzdisco.org – internet.

(2) Chan Parker, «?Ma vie en mi bémol», trad. Liliane Rovère, Plon, 1993.

(3) Intéressant musicien, disciple de Parker sans en être l’imitateur, complice du comique iconoclaste Lenny Bruce, Joe Maini disparut en 1964 sans doute au cours d’une partie de roulette russe.

(4) Il faut rappeler que Parker n’était pas seul à l’affiche, Sarah Vaughan, l’orchestre de Stan Getz, Timmy Rogers et quelques autres attractions complétaient le programme.

(5) Mark Myers, interview Roy Haynes, JazzWax, internet.

(6) Ira Gitler, «?From Swing to Bop?», Oxford University Press, New York, 1985.

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

The Gene Roland Orchestra feat.

Charlie Parker

«?The Band That Never Was?» LP Spotlite (G.B) SPJ 141

«?Bird Eyes vol.15?» CD Philology W 845-2

Charlie Parker and His Orchestra

À l’occasion de la publication du coffret «?Bird – The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve?», du fait de l’introduction d’inédits (faux départs et «?alternates?»), les numéros de prises de la séance du 6 juin 1950 ont été modifiés. Ce qui introduit une certaine confusion. Comme ces ajouts ne peuvent être pris en compte, pour plus de clarté nous avons choisi de nous en tenir à l’ancienne numérotation qui, elle-même varie selon les éditions. Ainsi l’indication concernant le «?master?» de Leap Frog alterne entre le prise 4 et la prise 6.

Café Society

Vis-à-vis de l’origine attribuée à ces enregistrements, on se trouve devant les mêmes divergences que celles exprimées à propos de la séance Parker/Navarro/Bud Powell (Birdland, 1950). Dans leur discographie consacrée à Charlie Parker, Piet Koster et Dick M. Bakker, comme Tom Lord et Walter Bruyninckx indiquent «?broadcast?» à l’origine de ces bandes - Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen n’en fait pas mention. Pour Norman Saks, Leonard Bukowski et Robert M. Bregman, auteurs de «?The Charlie Parker Discography?», on serait en présence d’enregistrements privés, ce qu’estime également Tony Williams qui donne comme responsable Bill Hirsh agissant pour le compte de Boris Rose. Ce qui est certain est que ces interprétations figuraient dans le fond du collectionneur impénitent de «?broadcasts?» qu’était ce dernier et qu’il en reproduisit des extraits à la demande avant de les publier sur des LP aux appellations fantaisistes.

Apartment Jam Sessions

Les enregistrements effectués au William Henry Apartment Building ont été réunis sur un 33 t. «?Charlie Parker - Apartment Jam Sessions?», Zim Records, repris à l’identique sur Spotlite (G.B.) SPJ 146.

Apollo Theatre

Les prestations de Charlie Parker à l’Apollo Theater du 17 au 23 août 1950 sont connues pour avoir été enregistrées de façon artisanale par Al Porcino, Don Lanphere et Jimmy Knepper. Toutefois, les différences de qualité sonore entre les sets, parfois entre les mêmes sets selon les supports, font douter de l’existence d’une source unique. Easy to Love du 23 août provient indéniablement d’une retransmission radiophonique et il n’est pas impossible que Repetition et What Is This Thing Called Love du 22 ainsi que le set du 23 ici reproduit - numéroté de 13 à 16 - aient une origine similaire étant donné la différence de qualité sonore qui les sépare des quatre sets suivants publiés sur «?Bird’s Eyes vol. 10» (Philology W 200-2).

A genuine “complete” set of the recordings left by Charlie Parker is impossible today and will remain so for a long time to come. Few musicians aroused so much passion during their own lifetimes and today, more than half a century after his disappearance, previously-unreleased music is published, and other titles – duly listed – will also come to light. A good many contain only solos by Bird, as they were recorded – privately – by musicians wanting to dissect his style. Regarding their sound-quality, most of them are at the limit: barely audible, sometimes almost intolerable, but in fact understandable: those who captured these sounds used portable recorders that wrote direct-to-disc, or wire-recorders, “tapes” (acetate or paper) and other machines now obsolete. Obviously they all produced sound-carriers that were fragile.

Of course, no solo ever played by Charlie Parker is to be disregarded. But a chronological compilation of almost everything he recorded – either inside a studio or on radio for broadcast purposes – does make it possible to provide an exhaustive panorama of the evolution of his style (Parker was, after all, one of the greatest geniuses in jazz), and to do so under acceptable listening-conditions. However, since we refer to style, the occasional presence here of some private recordings is indispensable, whatever the quality of the sound.

THE COMPLETE CHARLIE PARKER

STUDIO & RADIO VOLUME 8

“LAURA” 1950

After the prodigal nature of his indispensable string experiments, Norman Granz decided to record Bird with just a rhythm section, partnering him with nobody. It was a session which, quite wrongly, he declared to be a disappointment; and curiously, no-one who took part in it seems to have the slightest memory of what went on. But, beginning with I’m in the Mood for Love, Parker embroidered variations that were worthy equals for the ones that sprang from his imagination on Embraceable You or Don’t Blame Me. He makes Star Eyes sublime, for example, transforming it from the original, rather ordinary song which Jimmy Dorsey illustrated at the beginning of the Forties. Nor has Blues anything to envy from the two other performances here.

The period saw Bird at the centre of a curious adventure. Arranger Gene Roland, the man behind Woody Herman’s “Four Brothers” section, had organized a twenty-seven piece line-up in the studio as a setting for the gems improvised by Parker. Among the musicians were Red Rodney, Don Joseph, Don Ferrara, Eddie Bert, Jimmy Knepper, Joe Maini, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn and Don Lanphere; they convened in the Adams Theater in Newark, whose director took fright at the sheer size of the formation, a scare which the iconoclastic stand-up comic Lord Buckley somehow managed to circumvent. This plethoric group only left one calamitous recording for posterity, taped at a rehearsal in the Nola studios. Composed of fragments — only a version of It’s a Wonderful World seems to be complete — this tape sometimes gives a glimpse (rather than a clear hearing) of a few contributions from Parker and, probably, Zoot Sims.

The musical bulimia with which Bird seemed to be stricken drove him to suddenly turn up in places where he was least expected. One of them was the Renaissance Ballroom, where Machito and his orchestra were appearing: Parker’s interventions are so perfectly integrated that they don’t give the slightest impression of being collages. Mambo Fortunato sees the pianist (Rene Hernandez?) with a chance to take an excellent solo, and a trumpeter (Howard McGhee?) jumps in beautifully in the course of Lament for Conga (or Congo, depending on the release). Whoever they were, the result is remarkable. The same day (or maybe the day after), they say Bird joined the same band to play Reminiscing at Twilight: but no solo.

On more than one occasion, Dizzy Gillespie had let it be known that he wanted to be in the same studio with the new Parker, and his wish was granted when his contract with RCA Victor expired. Contrary to the conventions of the past, Dizzy would not be recognized as the session’s leader: set up for Norman Granz’ Clef label, the session would have Charlie Parker’s name on the can. Bassist Curley Russell was hired, and on drums there was Buddy Rich, whose presence was rather controversial: Roy Haynes would complain that he’d been ousted by Granz, and Granz left no argument unturned in defending himself, saying that he’d never imposed anything on anyone at a record-session. And he also claimed to remember that it was Bird himself who requested the assistance of Buddy Rich, who’d participated in the recordings with strings and also partnered Bird with JATP. Buddy was smart enough to resist all the fireworks people usually associated with his playing, and acquitted himself very honourably.

For the piano chair, Bird had set his heart on Thelonious Monk, who’d practically fallen into oblivion by this time (from July 1948 to July 1951 he didn’t lead a single session). On the other hand, none of his compositions was on the list. With just one exception, all the tunes were written by Parker: An Oscar From Treadwell, based once again on the harmonies in I Got Rhythm; two blues, Bloomdido and Mohawk; Relaxin’ with Lee, extrapolated from Stompin’ at the Savoy; and Leap Frog, which renewed with the fury of Bird’s conquest-years. In the course of the three versions that were released, the intensity of Bird’s exchanges in 8/8 with Rich and Dizzy provide reels of proof that time had no hold on their mutual understanding. Even so, Leap Frog required more than ten takes, including a number of false starts… The reason for the presence of My Melancholy Baby was just a private joke: during a gig at the Three Deuces, Parker and Gillespie had been victimized by a nuisance who was so drunk that he was yelling for them to play it for him. This romantic song composed in 1912 later went on to become a hit for Bing Crosby; Monk was inspired by the piece, and actually picked it up in his last-ever record-session. Here Parker embellishes it with a coda that absorbs Country Gardens, one of his favourite quotes.

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the Downtown Café Society. We’d like to present at this time for your listening entertainment the second edition of our show, and we’d like to open the show with a band number, one that was recorded and released not long ago by yours truly with strings. We hope you enjoy, without strings, equally as much, Just Friends...”

Charlie Parker opened at the Downtown Café Society on June 8th 1950. The place was almost a legend in Greenwich Village, where Barney Josephson had inaugurated the club in 1938. Barney voted for the Left, and when a journalist from the New York American Journal called his club “The wrong place for the Right people”, Barney adopted it as his slogan. His politics were diametrically opposed to those which prevailed at the Cotton Club. Barney threw segregation right out of the window, and even refused to hire artists whose attitude he found to be too “Uncle Tom”. This was where Billie Holiday brought Strange Fruit, Abel Meeropol’s inflamed song which passionately denounced lynching; Django Reinhardt had appeared here on his visit to The United States, and the careers of both Hazel Scott and Lena Horne were heavily indebted to the Downtown Café Society.

By 1950, things had changed a little. The political opinions of both Johnson brothers had drawn unwelcome attention from Senator McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Commission; Leon Josephson would even go to gaol, which provoked the indignation of Dashiell Hammett, who wrote to President Truman. In 1951, tired of it all, Barney closed the doors of his waning club for the last time.

Drummer Alan Levitt, a good friend of Bird, was sure that Parker derived little satisfaction from gigs that obliged him to play for dancers, which incidentally explains the entire background hubbub on these recordings. He remembered hearing Kenny Dorham and Roy Haynes advising Parker to look on the bright side, especially since the main attraction was the trio of Art Tatum, whom Parker worshipped. The admiration wasn’t mutual: during the execution of Tea for Two, Bird popped out of the wings at the end of a chorus and played his way onstage. Tatum told him to stop in no uncertain terms.

Due to the very reason for the existence of the quintet, Parker & Co. played compositions that were initially linked to the string ensemble: April in Paris, Just Friends, Easy To Love. Only one or two pieces belonged to Bird's usual repertoire: A Night in Tunisia which, curiously, as he'd done at Birdland with Fats Navarro, Parker handed over to Kenny Dorham, and Moose the Mooche, which benefitted from the presence of Tony Scott on clarinet (he'd dropped in to jam). On the three medleys preserved from this date, one of them — combining What’s New and It‘s the Talk of the Town — is played by Dorham and Al Haig.

Tony Scott returns to the picture in a lengthy version of Lover Come Back to Me, also from the Café Society, but the date it was recorded is impossible to determine. According to Dick Hyman, “The circumstances were that we had just played a night at Cafe Society with Tony Scott’s Quartet, and we were there six nights a week, and I played that engagement with him a number of times over the years. And then occasionally on the off night, on Sunday night, Bird came in late at night, at the closing set, which would have been around 3 o’clock, and he sat in with us. The other people in the band were: Irv Kluger, the drummer, and Irv Lang on bass. I’m pretty sure those were the people, though the personnel changed now and then. Those were the steady people for quite a while.”(1) Asked about the players involved in Lover Come Back To Me, Dick Hyman recognized it was probable that Mundell Lowe was the guitarist, with Brew Moore on tenor and Leonard Gaskin on bass. And he also confirmed that there was no other interpretation like this one on the tapes in his possession.

1950 was a crucial year for Parker, above all at a professional level: due to his drug-addiction, Red Rodney had been arrested on several occasions, leaving ripples in the midst of the quintet; and with the string ensemble keeping Bird quite busy, it became a habit for Parker to move around on his own, as he did in Sweden. Chan Richardson had this to say, “On May 29, 1950, until death did us part, I acknowledged the inevitable, and Kim and I became Bird’s family. We moved into his apartment on East 11th Street.”(2) From then on, Parker lived with his fourth companion and her daughter.

In June, Bird spent several Sundays at the William Henry Apartment Building on 139th Street and Broadway. Alto saxophonist Joe Maini had a basement squat over there — those who knew the place said it was quite sordid — and it was the scene for jam sessions that brought together people like Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Zoot Sims and Warne Marsh as well as Jimmy Knepper, Herb Geller or Jon Eardley. (3) A few fragments of what they used to play have survived, but unfortunately — maybe to save tape — what was kept amounts to little more than Bird’s contributions. You can justify it as a teaching-aid, but when these fragments are disconnected from their environment, they lose some of their meaning today, a half-century later.

Norman Granz set up a session and Parker went into the studio again with a string orchestra, a larger group this time with five violins, a viola, two cellos, a harp paired with a French horn, an oboe, plus a rhythm section comprised of Ray Brown, Buddy Rich, and pianist Bernie Leighton. On this occasion, most probably, Bird played a magnificent I Can’t Get Started for radio, accompanied by the bass/drums/piano trio alone.

Between then and the time he went to Sweden, leading his string ensemble (reduced to its original instrumentation), Bird appeared at Birdland (twice), the Apollo, the Blue Note in Chicago and the Harlem in Philadelphia, and was recorded by Granz again at Carnegie Hall at a JATP concert which confirmed Bird’s star status.

“I’d wanted strings since 1941.” Indeed. That was probably when Parker had liked Artie Shaw’s outfit, with the addition of a group of violins. Artie’s example was followed by Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, Harry James and Glenn Miller, but it’s difficult to imagine Bird asking Jay McShann to do likewise at that time. To be honest, Artie Shaw’s influence was no doubt decisive much later, when he appeared at Bop City in 1949 with his Symphony Orchestra after his New Music String Quartet recordings of two Alan Shulman arrangements, Mood in Question and Rendezvous for Clarinet and Strings. The scores which Bird was going to deal with were nothing so audacious.

The reverence which Parker showed for “serious” music was hardly a secret: in the Blindfold Test set up for Metronome magazine in 1948 by Leonard Feather, Bird expressed admiration for not only Stravinsky and Prokofiev, but also Ravel, Debussy, Hindemith, Wagner and Bach. Teddy Reig referred to Bird’s interest in Jacques Ibert’s Concertino da Camera for alto saxophone and eleven instruments, and said that he always asked Gil Evans to play Debussy’s Children’s Corner for him. Baritone saxophonist Danny Bank remembered hearing Bird practise parts from various classical works in his room at the Bryant Hotel. As for David Amram, the composer, conductor and horn-player, he admitted that it was Bird who had made him aware of the importance of Frederick Delius. Parker himself spoke of wanting to study with Stefan Wolpe and Edgar Varese. But for the time being he was a world away, facing arrangements performed by his own string section.

This time Norman Granz had convened Joe Lippman, whose principal quality was his love for Parker’s music. His scores aroused in Parker an enthusiasm that was slightly exaggerated, given that their primary virtue was their aim to give him as much freedom as possible. Even so, barely convinced by Lippman’s efforts on Easy to Love which he found too syrupy, he commissioned Jimmy Mundy to write a new score, and Mundy’s imagination produced an interlude that was rather unexpected in this context. The piece was premiered at the Apollo on August 23rd; carried away by enthusiasm, Bird attributed its paternity to Jimmy Mundy. It was actually composed by Cole Porter.

With the strings happy to keep to their role as accompanists, and Parker no longer with any real partner to joust with, Bird here found himself — with all due allowances — in the position of a concerto soloist. An additional constraint was that he didn't have a score to follow, so he had to improvise, and do so around a few well-used standards like Laura, Easy to Love or Out of Nowhere… There were hardly any exceptions save Neal Hefti's Repetition and Gerry Mulligan's Rocker, which Parker, true to his incomparable feeling for melody, makes his own without resorting to any of the reconstruction practised by boppers.

It was still a challenge to make the slimness of the repertoire go unnoticed. While he was at the Apollo, a group of six sets was recorded, and they contain four identical pieces of similar duration, played in the same order, and with each sequence lasting a bare ten minutes.(4) Bird manages to escape this straitjacket without copying himself; he multiplies the variations, sometimes infinitely small, between the different versions. In What Is This Thing Called Love, for instance, instead of stating the melody written by Cole Porter, he plays the paraphrase of Tadd Dameron’s Hot House. It’s a rarity, but unfortunately marred by the mediocre sound-quality.

When asked about what he felt in this context, Roy Haynes replied, “I love melodies, and a lot of the tunes Charlie Parker played with the strings were melodic. The strings format sometimes could be a little stiff. But he was trying to reach that audience, I think, and it seemed to work. It was cool, you know [laughing]. I don’t think that I’d want to do that all night, every night. And we didn’t. In fact, there were times when he’d stretch out on the strings stuff with the rhythm section and hang loose rather than play the arrangements as written.”(5) One of those times when he “stretched out” came in September 1952, at the Rockland Palace; the length of Rocker actually doubled. Patiently biding their time until it was their turn to restate the theme, the strings remained mute while the Bird took flight.

Gerry Mulligan was sharing the bill with Parker at the Apollo, as a member of the group led by Stan Getz, and he summed up the situation nicely: “There was one week that I worked with Charlie at the Apollo Theater. I worked it with the group that was based around a string band, with some incredibly stupid string section. I think three violins, a viola, and a cello. The very pedestrianness of the arrangements made the absolute perfect foil for Bird. ‘Cause later on, guys wrote more interesting arrangements, and the things were not nearly as effective. By the very simplicity of the arrangements, it was a better framework to hear Bird do what he could do. He’d play a bloody melody and would elevate it into something that was art.”(6)

Alain Tercinet

© 2014 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Dick Hyman interviewed by Mark Weber, Jazzdisco.org, internet.

(2) Chan Parker, “My Life in E-flat”, University of South carolina Press, 1998.

(3) An interesting musician — a Parker disciple, not his imitator — and an accomplice of the iconoclastic stand-up comic Lenny Bruce, Joe Maini died in 1964, probably in a game of Russian Roulette.

(4) Parker wasn’t the only one on the bill; Sarah Vaughan, Stan Getz and his band, Timmy Rogers and a few other attractions completed the programme.

(5) Roy Haynes interviewed by Mark Myers, JazzWax, internet.

(6) Ira Gitler, “From Swing to Bop”, Oxford University Press, New York, 1985

DISCOGRAPHICAL NOTES

The Gene Roland Orchestra feat.

Charlie Parker

“The Band That Never Was”, LP Spotlite (U.K.) SPJ 141

“Bird’s Eyes Vol. 15”, CD Philology W 845-2

Charlie Parker and His Orchestra

The numeration of takes from the June 6th 1950 session was modified for the release of the boxed-set “Bird – The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve”, due to the fact that unreleased takes had been added (false starts and “alternates”). The result was some confusion. As these add-ons can’t be included here, we decided to keep to the previous numbering system for clarity’s sake. Even those numbers vary according to the release: it explains why the master of Leap Frog is given alternately as Take 4 and Take 6.

Café Society

As regards the source attributed to these recordings, we find ourselves confronted by the same divergences as those mentioned for the session with Parker, Navarro and Bud Powell (Birdland, 1950). In their Charlie Parker discography, Piet Koster and Dick M. Bakker, like Tom Lord and Walter Bruyninckx, indicate the origins of these tapes as “broadcast”. Jorgen Grunnet Jepsen doesn’t mention them. For Norman Saks, Leonard Bukowski and Robert M. Bregman, the authors of “The Charlie Parker Discography”, these are private recordings, which is also the opinion of Tony Williams, who says Bill Hirsh was responsible on behalf of Boris Rose. What is certain is that that these performances were part of the resources amassed by the latter, Boris Rose, an unrepentant “broadcast” collector, and that he copied parts of them on request before issuing them on LPs with quaint names.

Apartment Jam Sessions

The recordings made at the William Henry Apartment Building were released on a 12” LP entitled “Charlie Parker - Apartment Jam Sessions” by Zim Records; they were identically released by Spotlite (U.K.) on LP SPJ 146.

Apollo Theater

Charlie Parker’s performances at the Apollo between August 17th and 23rd 1950 are known through makeshift recordings made by Al Porcino, Don Lanphere and Jimmy Knepper. However, the differences in sound-quality between various sets (and sometimes over a single set, depending on which sound-carrier was used) make you doubt the existence of a single source. Easy to Love dated August 23rd is undeniably from a radio broadcast, and it’s not impossible that Repetition and What Is This Thing Called Love dated August 22nd, and also the set on the 23rd which is included here — numbered from 13 to 16 — had similar origins, given the differences in sound-quality which separate them from the four sets that followed, released on “Bird’s Eyes Vol. 10” (Philology W 200-2).

discographie - CD 1

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as); Hank Jones (p); Ray Brown (b); Buddy Rich (dm). NYC, march/april 1950

1. STAR EYES (G. DePaul, D. Raye) (Norgran MGN 1035/mx. 371-4) 3’29

2. BLUES (Fast) (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8009/mx. 372-12) 2’47

3. I’M IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (Verve MGV 8009/mx. 373-2) 2’51

CHARLIE PARKER WITH MACHITO AND HIS AFRO-CUBAN ORCHESTRA

Charlie Parker (as) with Machito and His Afro-Cuban Orchestra : Howard McGhee, Mario Bauza, Frank “Paquito” Davilla, Bob Woodlen (tp); Gene Johnson, Fred Skerritt (as); Jose Madera, Frank Socolow (ts); Leslie Johnakins (bs); René Hernandez (p); Roberto Rodriguez (b); Jose Mangual (bongo); Luis Miranda (conga); Umbaldo Nieto (timbales); Frank “Machito” Grillo (maracas). poss. Renaissace Ballroomd, NYC, 19/5/1950.

4. LAMENT FOR CONGA (Machito) (Radio Transcription) 5’44

5. MAMBO FORTUNATO (Machito) (Radio Transcription) 5’13

CHARLIE PARKER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Dizzy Gillespie (tp); Charlie Parker (as); Thelonious Monk (p); Curley Russell (b); Buddy Rich (dm). NYC, 6/6/1950

6. BLOOMDIDO (C. Parker) (Mercury/Clef 11058/mx. 410-4) 3’26

7. AN OSCAR FROM TREADWELL (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8006/mx. 411-3) 3’21

8. AN OSCAR FROM TREADWELL (C. Parker) (master) (Mercury/Clef 11082/mx. 411-4) 3’23

9. MOHAWK (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8006/mx. 412-3) 3’49

10. MOHAWK (C. Parker) (master) (Mercury/Clef 11082/mx. 412- 6) 3’36

11. MY MELANCHOLY BABY (E. Burnett, G. A. Norton) (Mercury/Clef 11058/mx. 413-2) 3’24

12. LEAP FROG (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8006/mx. 414-4) 2’30

13. LEAP FROG (C. Parker) (master) ((Mercury/Clef 11076/mx. 414-6) 2’34

14. LEAP FROG (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8006/mx.414- ?) 2’00

15. RELAXIN’ WITH LEE (C. Parker) (Verve MGV 8006/mx. 415-2 3’57

16. RELAXIN’ WITH LEE (C. Parker) (master) (Mercury/Clef 11076/mx. 415-3 2’47

CHARLIE PARKER QUARTET

Charlie Parker (as); Bernie Leighton (p); Ray Brown (b); Buddy Rich (dm). NYC, mid 1950

17. I CAN’T GET STARTED (V. Duke, I.Gershwin) (poss. Radio Transcription) 4’53

discographie - CD 2

CHARLIE PARKER QUINTET

Kenny Dorham (tp); Charlie Parker (as); Al Haig (p); Tommy Potter (b); Roy Haynes (dm).

Café Society, NYC, 8/6/1950 – 6/7/1950

1. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 0’23

2. ANNONCE (Radio Transcription) 0’22

3. JUST FRIENDS I (J. Klenner, S. M. Lewis) (Radio Transcription) 3’05

4. ANNONCE (Radio Transcription) 0’13

5. APRIL IN PARIS I (V. Duke, E. Y. Harburg) (Radio Transcription) 3’16

6. A NIGHT IN TUNISIA (D. Gillespie, F. Paparelli) (Radio Transcription) 5’23

7. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 0’19

8. ANNONCE (Radio Transcription) 0’19

9. JUST FRIENDS II (J. Klenner, S. M. Lewis) (Radio Transcription) 3’03

10. ANNONCE (Radio Transcription) 0’13

11. APRIL IN PARIS II (V. Duke, E. Y. Harburg) (Radio Transcription) 3’02

12. MEDLEY 1 (BEWITCHED / SUMMERTIME)

(R. Rogers, L. Hart/G. Gershwin, Du Bose Heyward) (Radio Transcription) 5’07

13. MEDLEY II (I COVER THE WATERFRONT / GONE WITH THE WIND)

(J. Green, E. Heyman/A. Wrubel, H. Magidson) (Radio Transcription) 4’35

14. EASY TO LOVE (C. Porter) / 52nd STREET THEME(T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 5’01

15. MEDLEY III (WHAT’S NEW / IT’S THE TALK OF THE TOWN)

(B. Haggart, J. Burke / A. Neiberg, M. Symes) (Radio Transcription) 6’45

Tony Scott (cl) added

16. MOOSE THE MOOCHE / 52nd STREET THEME (C. Parker / T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 10’35

CHARLIE PARKER WITH THE TONY SCOTT QUARTET

Tony Scott (cl); Charlie Parker (as); Brew Moore (ts); Dick Hyman (p); Mundell Lowe (g); poss. Leonard Gaskin (b); poss. Irv Kluger (dm). Café Society, NYC, 1950

17. LOVER COME BACK TO ME (S. Romberg, O. Hammerstein II) (Radio Transcription) 17’12

18. 52nd STREET THEME (T. Monk) (Radio Transcription) 1’39

discographie - CD 3

CHARLIE PARKER with STRINGS

Charlie Parker (as); Joseph Singer (frh); Edwin Brown (oboe); Sam Caplan, Howard Kay, Sam Rand, Harry Melnikoff, Zelly Smirnoff (vln); Isadore Zir (viola); Maurice Brown (cello); Verley Mills (harp); Bernie Leighton (p); Ray Brown (b); Buddy Rich (dm); Joe Lippman (arr, cond). NYC, summer1950

1. DANCING IN THE DARK (A. Schwartz, H. Dietz) (Mercury/Clef 11068/mx. 442-5) 3’11

2. OUT OF NOWHERE (J. Green, E. Heyman) (Mercury/Clef 11070/mx. 443-2) 3’07

3. LAURA (D. Raskin, J. Mercer) (Mercury/Clef 11068/mx. 444-3) 2’58

4. EAST OF THE SUN (B. Bowman) (Mercury/Clef 11070/mx. 445-4) 3’39

5. THEY CAN’T TAKE THAT AWAY FROM ME (G. & I. Gershwin) (Mercury/Clef 11071/mx. 446-2) 3’20

6. EASY TO LOVE (C. Porter) (Mercury/Clef 11072/mx. 447-4) 3’30

7. I’M IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (Mercury/Clef MGC109/mx. 448-2) 3’34

8. I’M IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE (J. McHugh, D. Fields) (Mercury/Clef 11071/mx. 448-3) 3’30

9. I’LL REMEMBER APRIL (D. Raye, G. DePaul, P. Johnstone) (Mercury/Clef 11072/mx. 449-3) 3’07

CHARLIE PARKER with STRINGS

Charlie Parker (as), poss.Tommy Mace (oboe); Sam Caplan, Al Feller, Stan Kraft (vln); Dave Uchitel (viola); Bill Bundy (cello); Wallace McManus (harp); Al Haig (p); Tommy Potter (b); Roy Haynes (dm). Apollo Theatre, NYC, 22/8/1950

10. ANNONCE / REPETITION (N. Hefti) (poss. aircheck) 3’05

11. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE (C. Porter) /DÉSANNONCE (poss. aircheck) 3’02

Same 23/8/1950

12. ANNONCE / EASY TO LOVE (C. Porter) (Radio Transcription) 3’08

13. REPETITION (N. Hefti) (poss. Radio Transcription) 2’41

14. APRIL IN PARIS (V. Duke, E. Y. Harburg) (poss. Radio Transcription) 3’11

15. EASY TO LOVE (C. Porter) (poss. Radio Transcription) 2’14

16. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE (C. Porter)/ DÉSANNONCE (poss. Radio Transcription) 2’51

17. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE (C. Porter) (private recording) 2’08

CHARLIE PARKER with STRINGS

Charlie Parker (as); Tommy Mace (oboe); Sam Caplan, Stan Karpenia, Teddy Blume (vln); Dave Uchitel (vla); Bill Bundy (cl); Wallace McManus (harp); Al Haig (p); Tommy Potter (b); Roy Haynes (dm); Joe Lippman, Jimmy Mundy *, Gerry Mulligan ** (arr). Carnegie Hall, NYC, 17 septembre 1950

18. WHAT IS THIS THING CALLED LOVE (C. Porter) (Norgran MGJC 3502) 2’52

19. APRIL IN PARIS (V. Duke, E. Y. Harburg) (Norgran MGJC 3502) 3’10

20. REPETITION (N. Hefti) (Norgran MGJC 3502) 2’46

21. EASY TO LOVE* (C. Porter) (Norgran MGJC 3502) 2’23

22. ROCKER ** (G. Mulligan) (Norgran MGJC 3502) 3’00

«?Mélodie. S’il fallait sous la torture, et une torture féroce, n’en garder qu’une seule, ça serait Laura. Jouée par Charlie Parker, elle met le pied dans la porte du Paradis. Des petites volutes de bonheur à l’état pur sans mélange. Rien ne peut gâcher ce moment où je l’écoute.?»

Jean-Pierre Marielle (Le grand n’importe quoi, Calmann-Lévy, 2010)

“Melody... If you were being tortured and could only keep one — even if the torture was fierce — then it would have to be Laura. Played by Charlie Parker, Laura steps through the gates of Paradise wreathed in little scrolls of pure, undiluted happiness. Nothing can spoil that moment every time I hear it.”

(J.-P. Marielle in “Le grand n’importe quoi”, Calmann-Lévy, 2010)

CD The Complete Charlie Parker - Intégrale Charlie parker vol. 8 Laura 1950, Charlie Parker © Frémeaux & Associés 2014