- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

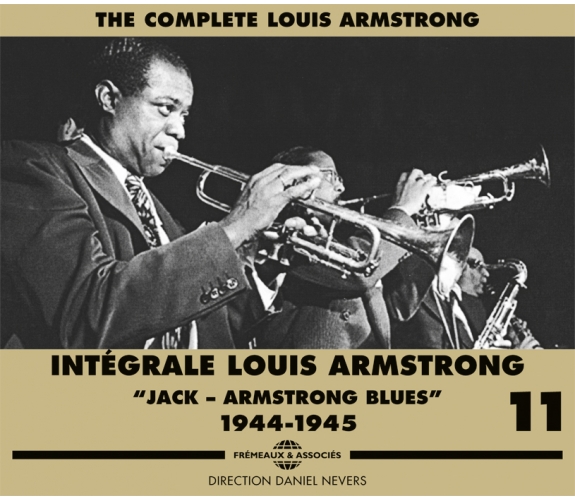

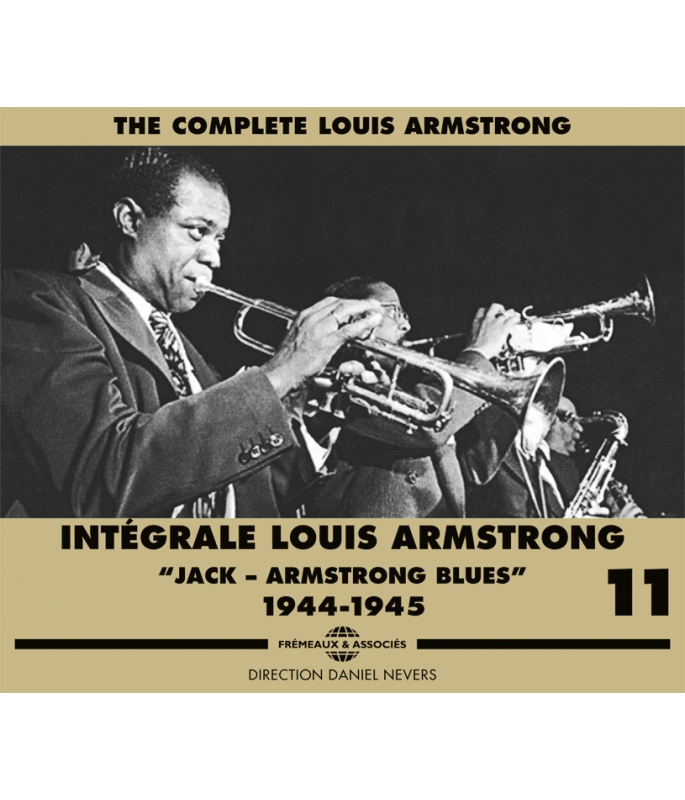

JACK - ARMSTRONG BLUES - 1944-1945

Ref.: FA1361

EAN : 3561302136127

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 26 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JACK - ARMSTRONG BLUES - 1944-1945

JACK - ARMSTRONG BLUES - 1944-1945

“You can’t play nothing on trumpet that doesn’t come from him, not even modern shit. I can’t ever remember a time when he sounded bad. Never. Not even one time. He had great feeling up in his trumpet and he always played on the beat. I always just loved the way he played and sang.” Miles DAVIS

The Frémeaux & Associés Complete Series usually feature all the original and available phonographic recordings and the majority of existing radio documents for a comprehensive portrayal of the artist. The Louis Armstrong series is an exception to the rule in that the selection of titles by this American wizard is certainly the most complete as published to this day but does not comprise all his recorded works. Patrick FREMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Présentation et Esquire BounceLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertLeonard Feather00:03:261944

-

2I Gotta Right To Sing The BluesLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertFields00:03:431944

-

3Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertLouis Russell00:03:341944

-

4Muskrat RambleLouis Armstrong - Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertEd Ory00:02:161944

-

5Lazy RiverLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraArodin00:04:121944

-

6Presentation et Ain't Misbehavin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraAndy Razaf00:04:241944

-

7I Lost My Suger In Salt Lake CityLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJimmy Lange00:03:191944

-

8A Pretty Girl Is Like A MelodyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraIrving Berlin00:03:121944

-

9Swanee RiverLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraMusique Traditionnelle00:03:151944

-

10Baby Don 't You CryLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraAnonyme00:04:321944

-

11Don't Sweetheart MeLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraGill00:02:441944

-

12Groovin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraO. Nan00:00:561944

-

13Easy As You GoLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraOno Rene00:02:571944

-

14I Couldn't Sleep A Wink Last NightLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDelange00:02:541944

-

15Keep On Jumpin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Russell00:03:371944

-

16No Love No NothingLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Robin00:02:331944

-

17Is My Baby Blue TonightLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCaplin00:02:201944

-

18Blues In The NightLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJ. Mercer00:03:271944

-

19Kep On Jumpin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Russell00:03:221944

-

20Stompin' At The SavoyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraDelange00:02:451944

-

21Solid SamLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraTed McRae00:02:431944

-

22Harlem On Parade And Ain't MisbehavinLouis Armstrong, Dorothy DandridgeJohnny Mercer00:03:501944

-

23Whatcha SayLouis Armstrong, Dorothy DandridgeAndy Razaf00:01:411944

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Whatcha SayLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraTed Koehler00:03:041944

-

2Groovin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraO. Nan00:02:521944

-

3Baby Don't You CryLouis Armstrong and his Orchestra00:02:561944

-

4King Porter StompLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraF. Morton00:02:461944

-

5Its Love Love LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraTed Koehler00:02:131944

-

6Ain't Misbehavin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraAndy Razaf00:03:061944

-

7LouiseLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Robin00:02:281944

-

8Goin My WayLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraBurke00:02:351944

-

9Groovin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraO. Nan00:02:311944

-

10Is You Is Or Is You Ain't My BabyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraC. Tobias00:02:501944

-

11PerdidoLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJuan Tizol00:02:351944

-

12Ain't Misebehavin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraAndy Razaf00:03:141944

-

13Keep On Jumpin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Russell00:03:161944

-

14Swingin On A StarLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraBurke00:02:201944

-

15Confessin'Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraBurke00:03:271944

-

16Dance With The DollyLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraAnonyme00:03:091944

-

17Jack Armstrong BluesLouis Armstrong and the V-Disc All StarsJack Teagarden00:05:011944

-

18Jack Armstrong BluesLouis Armstrong and the V-Disc All StarsJack Teagarden00:03:381944

-

19Confessin'Louis Armstrong and the V-Disc All StarsDougherty00:03:151944

-

20Confessin'Louis Armstrong and the V-Disc All StarsDougherty00:03:191944

-

21Jodie ManLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraA. Roberts00:03:191945

-

22I WonderLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCecil Gant00:03:021945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Presentation And Confessin'Louis Armstrong - Second Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertReynolds00:06:121945

-

2Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong - Second Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertL. Russell00:02:301945

-

3Basin' Street BluesLouis Armstrong - Second Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertSpencer Williams00:01:031945

-

4Things Ain't What They Used To BeLouis Armstrong - Second Esquire All-American Jazz ConcertMercer Ellington00:02:161945

-

5On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:04:251945

-

6Accentuate The PositiveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:04:281945

-

7I Can't Give You Anything But LoveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraD. Fields00:02:401945

-

8AlwaysLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraIrving Berlin00:03:031945

-

9It Ain T Me 1Louis Armstrong and his OrchestraPalmer00:03:021945

-

10Confessin' And Blame It On MeLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraReynolds00:04:561945

-

11It Ain't MeLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraPalmer00:03:471945

-

12CaldoniaLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraF. Moore00:03:011945

-

13Theme And PresentationLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraInconnu00:01:471945

-

14Accentuate The PositiveLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJohnny Mercer00:04:561945

-

15On The Sunny Side Of The StreetLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraD. Fields00:03:151945

-

16I WonderLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraCecil Gant00:03:321945

-

17Blue Skies And One O' Clock JumpLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraIrving Berlin00:03:271945

-

18Back O' Town BluesLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraL. Russell00:03:361945

-

19Me And Brother BillLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraLouis Armstrong00:02:431945

-

20PerdidoLouis Armstrong and his OrchestraJuan Tizol00:02:451945

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Intégrale Louis Armstrong Volume 11 FA1361

THE COMPLETE louis armstrong

INTÉGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG

“JACK – ARMSTRONG BLUES”

1944-1945

Volume 11

DIRECTION DANIEL NEVERS

Louis ARMSTRONG - volume 11

Á Olivier BRARD (1949-2011) & Jean “Nonoss” DUROUX (1922-2011)

Cette onzième livraison de l’intégrale Louis Armstrong ne manque pas de ressembler fortement à la dixième (Frémeaux & Associés FA-1360). Même période sombre, troublée, de la première moitié des années 1940?; même interminable grève des enregistrements destinés à la vente publique (1942-44)?; même effort de guerre demandé à tous, musiciens compris?; même position dominante de la radio militaire (AFN)… Néanmoins, on y croisera les légendaires V-Discs, jusque là absents du cursus armstrongien, et on y trouvera enfin de vrais concerts donnés devant un vrai public, à des lieux des bidouillages pratiqués sur une vaste échelle depuis 1942 par l’AFN, afin de conférer un poil de vie à ce qui n’était en somme que des séances de studio (voir texte du volume 10, sur ces histoires de montage et de mixage, entre musique, présentation, interviews, rires et applaudissements en conserve)…

Le plus mémorable de ces vrais concerts – l’un des plus fameux de l’histoire du jazz – fut donné le 18 janvier 1944 dans le cadre pour le moins inhabituel du Metropolitan Opera de New York : le

«?Met», comme ils disent là-bas… Le jazz avait certes déjà trouvé droit de cité durant les années 1930 dans des salles réputées comme «?Carnegie Hall?», mais cette fois ce n’était pas tout à fait la même chose. «?Carnegie Hall?», comme «?Pleyel?» ou «?Gaveau?» à Paris, est un établissement que tout un chacun peut louer, dès l’instant que des dates sont libres et que le locataire dispose de quelque menue monnaie sur son compte en banque. Tandis que le «?Met?» se mérite et que c’est lui qui invite, comme tout véritable théâtre subventionné. C’est bien évidemment au caractère exceptionnel de l’époque que le jazz eut l’honneur de pénétrer dans ce temple de la musique sérieuse.

Depuis 1936, deux des revues musicales concurrentes les plus lues, Metronome et Esquire, organisaient un referendum annuel auprès de leurs lecteurs, afin de désigner les musiciens vedettes de l’année écoulée. A partir de celui portant sur 1938, il fut décidé que désormais on ferait enregistrer, à la fin de l’an en question ou au début du suivant, par certains des élus quelques galettes souvenir, produites par l’une ou l’autre grosse boîte phonographique, RCA-Victor et Columbia. Cette pratique se poursuivit jusque dans les années 1950. On trouvera les résultats de ces jam-sessions dans le recueil réalisé avec sa fougue coutumière par Pierre Lafargue, intitulé Summit Meetings (Frémeaux FA-5050)… Il y a naturellement fait figurer quelques uns des vainqueurs Esquire pour l’an 1943 (voir CD 1, plages 12 à 15) – ceux qui purent se rendre au studio le 4 décembre. Cette fois-là, RCA et Columbia, toujours hors course à cause de la grève, cédèrent le pas et c’est la jeune firme de Milt Gabler, Commodore, qui récupéra la séance. Louis Armstrong n’en fut point – peut-être parce que son impresario glouton Joe Glaser n’y tenait pas plus que cela. Il est vrai que Roy Eldridge, Jack Teagarden et Barney Bigard n’y vinrent pas davantage, alors qu’ils se retrouvèrent en bonne place sur la scène du «?Met?» le mois suivant en compagnie de Louis, Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum, Al Casey, Oscar Pettiford, Sidney Catlett et quelques autres. En revanche, ni Cootie Williams ni Edmund Hall, pourtant nommés parmi les lauréats et présents le 4 décembre, ne jouèrent au concert… A noter, à l’endroit de ce référendum, que pour une fois, ce ne furent point les lecteurs d’Esquire qui votèrent, mais les plus célèbres critiques (ou assimilés) de l’heure : des Américains bien sûr, comme Paul Eduard Smith, George Avakian, Bob Thiele, Barry Ulanov ou John Hammond, mais aussi quelques étrangers (parfois réfugiés), tels le Baron danois Timme Rosenkrantz, le très britannique Leonard Feather (par ailleurs organisateur de l’opération) et le poète belge Robert Goffin, l’un des premiers ayant écrit de belles pages sur cette musique (Aux Frontières du Jazz, 1932 – avec pour dédicataire un certain Armstrong Louis) et qui avait alors sur le feu une biographie romancée du trompettiste. On leur a parfois reproché de n’avoir choisi que des valeurs sûres, alors que le pays regorgeait de petits jeunes bourrés de talent. C’est faire totalement fi du contexte : ce concert participait de l’effort de guerre et ne visait en rien à révéler les nouveaux venus, aussi bons soient-ils… Leur heure viendra, qu’on ne se bile pas !

Deux jours avant le grand soir, soit le 16 janvier 1944, eut lieu, dans le cadre de l’alors célèbre série Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street, produite par NBC (puis par ABC), une émission promotionnelle de ce concert exceptionnel. Cette fois, la formation de base est, à deux absents près, celle que pourront entendre quarante-huit heures plus tard les heureux acheteurs d’un billet pour le «?Met?». Les trois titres faisant intervenir Louis, Basin Street Blues, Esquire Blues et Honeysuckle Rose, sont reproduits sur le CD 3 du volume 10 (plages 15 à 17).

Le concert de légende du 18 janvier fut intégralement enregistré par les services de l’AFRS qui en diffusèrent des extraits en différé, tandis qu’un puissant sponsor, producteur d’une pétillante boisson non alcoolisée des plus connues, en fit transmettre une partie en direct, via le Blue Network d’ABC dans cette collection intitulée Victory Parade of Spotlights Bands. De plus, quelques morceaux (notamment Basin Street Blues et Back O’ Town) furent par la suite édités en V-Discs… Des morceaux, on en joua près d’une trentaine, en commençant par Esquire Blues et en terminant, comme il se doit, par l’Hymne national. Pour qui concerne Satchmo, il intervient sur treize de ces titres – parfois, il est vrai, de manière fort discrète, presque inaudible. Il ne nous a pas paru nécessaire de tous les inclure ici et nous n’avons retenu que I Gotta Right to Sing the blues, Back O’ Town Blues et Muskrat Ramble, trois de ceux qui le mettent le mieux en valeur, ainsi que la présentation des musiciens sur Esquire Bounce… On sourira en écoutant Coleman Hawkins se prêter au jeu et intervenir sur des thèmes qui ne constituaient pas vraiment son ordinaire, lui qui, en ce même mois de janvier 44, enregistrait avec… Dizzy Gillespie ! L’intégrale du concert ne manquera certainement pas d’être rééditée par nos soins dans un avenir pas trop lointain. Il sera bon d’y ajouter les extraits de l’émission du 16 janvier dans lesquels Louis ne joue pas…

Tiens, au fait, un petit orchestre comprenant Louis Armstrong, Big Tea, Bigard, Big Sid Catlett… Suffit de remplacer Tatum par Earl Hines et Pettiford par un petit nouveau et le tour est joué. Ces garçons iront loin d’ici pas si longtemps. Affaire à suivre…

Un an moins un jour plus tard, le 17 janvier 1945 donc, se déroula le Second Esquire All American Jazz Concert, toujours basé sur l’avis des critiques, mais conçu de manière assez différente, faisant intervenir des vainqueurs jouant en trois lieux fort éloignés les uns des autres : le «?Municipal Auditorium?» de La Nouvelle Orléans (avec Louis, Bechet, James P. Johnson, Paul Barbarin), les studios de Blue Network à New York (avec le Quintette de Benny Goodman et la chanteuse Mildred Bailey) et le «?Philarmonic Auditorium?» de Los Angeles (avec l’orchestre de Duke Ellington). Il semble que les enregistreurs de l’AFRS aient boudé cette audacieuse tentative de «?triplex?» et laissé le champ libre à la seule chaîne ABC qui ne put diffuser que des extraits – pas nécessairement les meilleurs ni les plus intéressants ! – des trois concerts simultanés. On raconte, certes, que l’intégralité de ce qui se donna en chaque lieu fut enregistrée, mais au jour d’aujourd’hui, on ne dispose toujours que de ces brefs fragments ne rendant guère compte de l’ampleur de la manifestation. Ainsi, par exemple, sur Basin Street Blues (CD 3, plage 3), Armstrong devait dialoguer avec celui qu’il considérait lui-même comme son premier maître (avant King Oliver), Willie “Bunk” Johnson (1879-1949), cornettiste de son enfance, oublié puis redécouvert par les archéologues du jazz au début des années 1940. Malheureusement, tel qu’il nous est parvenu, le morceau dure à peine plus d’une minute, puis on rend l’antenne à New York ! Un rendez-vous unique manqué entre le maître et l’élève. En tendant bien l’oreille, on perçoit dans le lointain, tandis que Louis chante, quelques notes de cornet : le vieux “Bunk”, sûrement… A la fin, après une présentation de Leonard Feather, on aurait dû écouter tranquillement cette composition éminemment ellingtonienne Things Ain’t What They Used to Be, jouée de conserve par le big band en Californie, le clarinettiste au cœur de la Grosse Pomme et le trompettiste du côté des Bayous… Mais, là encore, les choses ne marchent comme elles le devraient et le tout s’interrompt au bout de deux minutes… Du moins peut-on entendre brièvement Louis – pas tellement sûr de lui d’ailleurs – en soliste… Autre rendez-vous manqué, car Satchmo n’enregistra jamais avec le grand orchestre ducal.

Autre déception, ce Tribute to Fats Waller du 11 février 45 diffusé par la chaîne WNEW. Flanqué des membres du Rhythm de Fats (Herman Autrey, Gene Sedric, Al Casey…), Louis trouve moyen de ne pas jouer une seule composition du rabelaisien Roi du piano stride qui avait lâché tristement ses admirateurs au petit matin blême du 15 décembre 1943 en gare de Kansas City. Armstrong le tenait pour un “solid sender” et les connaissait pourtant bien ces thèmes?; il en avait même créé quelques uns comme Black and Blue, Sweet Savannah Sue et surtout Ain’t Misbahavin’ ! La qualité sonore du document en notre possession étant moyenne, nous n’avons point inclus ici ces versions supplémentaires d’On the Sunny Side et de I Got Rhythm.

Outre les concerts mémorables, les engagements ne manquèrent pas en 1944-45, notamment au «?Trianon Ballroom?» de Southgate (Californie), au «?Club Zanzibar?» de New York, ou ailleurs. Par exemple sur les bases d’entraînement militaires comme Camp Reynolds (Pennsylvanie), le Tuskegee Army Airfield (Alabama) ou Fort Huachuca (Arizona). Lors de ses séjours sur la Côte Ouest, Louis, qui avait renoué avec le cinéma en 1942 (Cabin in the Sky – voir volume 10) après plusieurs années loin des sunlights, décrocha deux nouveaux rôles épisodiques au printemps et à l’été de 1944. Dans chaque cas, il eut pour partenaire Dorothy Dandridge. Réalisé par Ray McCarey, Atlantic City, le premier, produit par le studio Republic, faisait également intervenir Paul Whiteman et son orchestre ainsi que Buck and Bubbles. Après quelques notes sur la fin de Harlem on Parade (chanté par Dorothy), Satchmo reprend Ain’t Misbehavin’ (ce qu’il aurait dû faire au cours de l’hommage à son compositeur !), modifie légèrement les paroles, puis introduit les duettistes (CD 1, plage 22). L’orchestre à l’image est bien celui d’Armstrong à l’époque, mais il est presque certain que ce n’est pas lui que l’on entend !... Le second film, dirigé par Vincent Sherman pour Warner Bros., Pillow to Post, avec la lumineuse Ida Lupino, offre un nouvel air partagé avec Dorothy, Whatcha Say… On cite parfois un troisième film, également produit par Warner en 44 et réalisé par Delmer Daves, Hollywood Canteen : une de ces nombreuses revues «?all-stars?» proposées entre 1942 et 1945 par les différents studios dans leur «?effort de guerre?». On peut donc y croiser la plupart des piliers de la firme : Ida Lupino, Eddie Cantor, Paul Henreid, Peter Lorre, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Dorothy Malone, Eleanor Parker, Roy Rogers, Barbara Stanwick, Jane Wyman, Jack Benny, Jimmy Dorsey et son orchestre, Carmen Cavallaro, les Andrews Sisters… Mais d’Armstrong point – du moins, dans les copies visionnées. Est-il possible qu’une séquence à lui consacrée ait été éliminée au montage, comme dans le Doctor Rhythm de 1938 ? Peu probable…

Le 9 août 1944, deux mois et trois jours après le débarquement de Normandie, alors que la bataille fait rage en Europe, Louis accomplit sa rentré dans les studios Decca de Los Angeles, après plus de deux ans d’absence. Il y grave une version disque de Whatcha Say (différente de la bande-son du film), toujours en compagnie de Dorothy Dandridge, ainsi que deux autres faces, Groovin’ et Baby Don’t You Cry. Tout cela ne sera édité que des années plus tard… En revanche, les deux nouveautés inaugurant dès le 14 janvier l’an 45, Jodie Man et I Wonder, dans lesquelles Satchmo est accompagné par une formation de studio, furent très vite mises à la disposition des amateurs, y compris en Europe. Probablement pour bien montrer que tout – ou presque ! – était rentré dans l’ordre…

En réalité, au mois d’août 44, la grève des enregistrements dits commerciaux durait toujours, mais depuis novembre 1943, elle avait évolué. Du 1er août 1942 jusqu’à cette date, elle fut totale : toutes les firmes, petites ou grandes, anciennes ou récentes, étaient concernées dans ce pays où il n’est guère facile de tricher. Les grandes anciennes en profiteront pour rééditer et pour sortir des inédits des archives. Celles n’ayant rien à rééditer et ne possédant pas d’archives… feront ce qu’elles pourront. Fin 43, la situation devenant intenable, les petits producteurs acceptèrent les conditions imposées par le syndicat des musiciens et purent se remettre à l’ouvrage. Ainsi Signature, la marque fondée en 1940 par Bob Thiele, enregistra-t-elle dès décembre de superbes faces par Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Dicky Wells, Barney Bigard… Keynote, Blue Note, Allegro, Apollo et autres, en firent autant. Seule parmi les «?grosses?» (mais de fondation récente) la maison Decca leur emboîta le pas. Voilà pourquoi quelques célébrités, dont Louis Armstrong, se remirent à faire des disques dès le printemps 1944. En revanche, les deux mammouths, RCA et Columbia, ne voulurent rien savoir. Ce qui fait que la grève continua juste pour ces deux-là ! Elle se termina quand même un jour : le 11 novembre 44. Peut-être parce que c’était l’anniversaire de l’armistice ?

Bien entendu tout ceci ne concerne que les disques destinés à la vente au public. La grève ne s’applique pas aux enregistrements effectués pour la radio ou le cinéma. Elle ne s’attaque pas davantage à cette légendaire série de 78 tours de trente centimètres de diamètre (neuf cent cinq galettes distribuées d’octobre 43 à mai 49 – plus de huit millions de disques pressés, la plupart dans une sorte de vinyle primitif), mondialement connus sous le nom de «?V-Discs?» (les «?disques de la Victoire?»).

Avec New York comme QG (au contraire de l’AFRS basé à Los Angeles), l’entreprise, sous la direction du Lieutenant George Robert Vincent, vétéran de la maison Edison, commença vraiment à tourner à partir de l’été de 1943. Ses concepteurs (Steve Sholes, Morty Palitz, Walt Heebner, Tony Janak et quelques autres) avaient tous, dans le civil, travaillé dans les studios du phonographe et de la radio?; certains y retourneront après la guerre. Contrairement aux transcriptions destinées à la radio (militaire ou non) et livrées uniquement aux diverses stations censées les diffuser, les V-Discs furent régulièrement envoyés aux GIs, aux soldats en campagne sur le théâtre même des opérations, et joués par eux pendant les pauses, les moments de repos. En 1944-45, expédiées par boîtes de trente disques chaque mois, il y eut deux séries distinctes avec numéros de catalogue différents, la plus abondante destinée à l’armée de terre, l’autre à la navy… Pour constituer son catalogue, l’équipe V-Disc s’abreuva allègrement à toutes les sources possibles : enregistrements plus ou moins anciens prêtés par les firmes (on connaît des reprises d’Ellington de 1930 !), fragments de concerts et d’émissions radiophoniques (AFN et transcriptions de réseaux commerciaux), bandes-son de films… Et surtout, il y eut les séances spéciales V-Disc, organisées régulièrement dès l’automne 43 principalement chez RCA et NBC. L’un des premiers à venir, mi-septembre, fut Fats Waller – son ultime séance d’enregistrement…

Le jazz, au sens large (c’est-à-dire, comprenant musiciens et orchestres blancs !), constitue à peu près un tiers du répertoire V-Disc, mais certains ne participèrent jamais aux séances spéciales, tel Duke Ellington, pourtant bien représenté sur le label. Basie, en revanche, en fit beaucoup. Quant à Satchmo, il se contenta de la session des 6 et 7 décembre 1944, divisée en V-Disc All Star Jam Session et Louis Armstrong and the V-Disc All Stars, soit deux titres (mais avec chacun deux «?prises?» : celles éditées en leur temps se trouvent en positions 18 et 19 sur le CD 2) dans lesquels Louis et Teagarden semblent se retrouver avec un plaisir non dissimulé. Et ils le prouvent en intitulant leur composition commune Jack – Armstrong Blues. Un nouveau clin d’œil pour la suite…

Dans ce qui vient d’être évoqué, à l’exception de la courte séquence d’Atlantic City et des retrouvailles avec Decca le 9 août 44, Armstrong n’est guère entouré de son orchestre régulier, mais c’est bien en sa compagnie qu’il remplit la plupart des engagements dans les clubs et qu’on le retrouve sur les transcriptions de l’AFRS. La formation s’est de nouveau modifiée entre la fin 1943 et les premiers mois de 44. On ne sait pas très bien pourquoi des gens comme Bernard Flood (tp), Henderson Chambers (tb) et surtout Joe Garland, saxophoniste et directeur musical ayant remplacé Luis Russell à ce poste, s’en allèrent à cette époque. On peut évidemment soupçonner Joe Glaser de les avoir poussés sans délicatesse vers la sortie. Toujours est-il qu’à l’heure du concert au «?Met?», un autre saxophoniste ténor, Teddy McRae, récupéra le rôle de Garland et fut chargé de constituer un nouveau groupe. C’est celui que l’on entend, avec parfois de légers changements, dans les radios de 1944-45. Après un an d’absence, Velma Middleton, la dodue chanteuse/danseuse, est de retour et restera jusqu’en 1947. Quant au trompettiste qui monte assez haut dans l’aigu, il s’agit probablement d’Andrew “Fatso” Ford, à qui Louis abandonne volontiers des exercices qui ne le tentent plus guère. Irakli, notre Satchmo franco-géorgien, remarque qu’au fond, Pops n’a jamais tellement raffolé de ces interprétations swing en dents de scie alors très goûtées du public qu’il ne pouvait éviter d’inclure au répertoire, lui qui leur préférait de loin des choses plus calmes, plus

«?assises?», susceptibles d’accéder à une majesté certaine…

Dans l’orchestre de 1944, honnête mais sans surprise, on se doit néanmoins de signaler la présence, de la mi-mai à la mi-septembre, d’un saxophoniste de vingt et un printemps – encore un ténor, qu’il fallut faire accepter à McRae ! – à qui l’on prédisait un bel avenir : Dexter Gordon. On l’entend, fougueux comme l’y autorisait son jeune âge, sur trois versions d’Ain’t Misbehavin’, deux de Keep On Jumpin’, plus Stompin’ at the Savoy, King Porter Stomp et Perdido (répartis sur les CDs 1 et 2). Louis, qui l’interpelle souvent au moment de ses solos (“brother Dexter !”), l’avait pris en affection comme des années plus tôt, lors de son premier séjour sur la Côte Ouest, ce jeune batteur à qui il avait permis de jouer du vibraphone, Lionel Hampton… En septembre Dexter rejoignit la formation du chanteur Billy Ekstine.

Pour le reste, on notera qu’en 1944-45, les deux séries de l’AFRS sur lesquelles on trouvait le plus souvent Louis Amstrong l’année précédente, Jubilee et Downbeat, ont cédé la place à Victory Parade of Spotlight Bands (collection d’ABC partagée avec Coca Cola) et One Night Stand (série dédié à la danse «?hot?»)… On sait qu’il en manque, notamment les Victory Parade 277 (5 février 44) et 319 (25 mars). Et, comme précédemment, il faut se méfier, car un même morceau, dans la même version, peut se retrouver sur plusieurs de ces grands disques diffusés à des dates différentes, parfois à huit mois d’écart. Par contre, il peut aussi s’agir de versions différentes (voir, à ce propos, le texte du volume 10) ! Les enregistrements effectués au Club Zanzibar de New York entre décembre 44 et mars 45 offrent un bon exemple de ce diabolique méli-mélo : il existe au moins trois versions d’Accentuate the Positive, une pièce que Louis interprétait chaque soir à l’époque. Elles figurent sur trois transcriptions différentes mais, manifestement, proviennent de la même source. La troisième (non reproduite ici) fut même incluse sur l’AFRS “New Year” et diffusée le 31 décembre 1945, en même temps que seize autres morceaux par d’autres artistes – soit quelque neuf mois après sa captation…

Bien entendu, les difficultés tiennent surtout au répertoire passablement répétitif qui, comme d’ordinaire, nous apporte son lot – au demeurant toujours agréable à écouter – de Basin Street Blues, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Confessin’, Ain’t Misbehavin’, On the Sunny Side of the Street, King Porter Stomp, l’inévitable Brother Bill, Lazy River, Perdido, sans oublier l’indicatif, When It’s Sleepy Time… Toutefois, on peut être sûr que toutes les versions de ces airs ici reprises (ainsi que celles de thèmes plus récents comme Blues in the Night, Groovin’, Keep on Jumpin’, I Lost my Sugar in Salt Lake City, Accentuate…) sont différentes les unes des autres et/ou de celles déjà proposées dans le précédent recueil. Il faut encore signaler que, dans le tas, on tombe de temps en temps sur des pièces qu’Armstrong n’a que rarement enregistrées commercialement – voire pas du tout : A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody, Solid Sam, Louise, Going My Way (coup de chapeau à l’ami Bing Crosby oscarisé), Swanee River, Swingin’ on a Star, Always, It’s Love, Love, Love, Stompin’ at the Savoy, Don’t Sweetheart Me… La plupart ne sont évidemment que les petites rengaines d’à peine une saison, mais avec Louis Armstrong aux commandes, on en redemande !... Prenons l’AFRS Spotlight Bands n°503, quarante centimètres serré dans la collection de Charles Delaunay qui offre des versions de Louise, Lazy River, Is You Is or Is You Ain’t my Baby, Groovin’, ainsi qu’un I Walk Alone sans Louis. L’état d’atroce décomposition de la chose n’incitait guère à inclure ces titres puisque, aussi bien, on en a déjà repiqué moult autres moutures fort semblables, provenant sans doute des mêmes séries d’enregistrements. Tous, sauf Dance with the Dolly, que Satchmo paraît bien n’avoir donné qu’une fois. Aucune autre trace, en tous cas, dans sa discographie. Pas question d’hésiter : nous l’avons inclus (CD 2, plage16), malgré la tempête qui fait rage et trempe jusques aux os la pauvre petite poupée de chiffons. Au fond, cela pourrait être du ragtime ! Mais Louis Armstrong valait bien cela.

Daniel NEVERS

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés - Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

For & Jean “Nonoss” Duroux (1922-2011)

This eleventh volume of Louis Armstrong’s complete recordings closely resembles N° 10 (Frémeaux FA 1360): it covers the same dark, troubled times – the first half of the Forties – which saw the same, everlasting recording-bans depriving civilians of new records (1942-44) while the same, rigorous contributions to the war effort were demanded of everyone, musicians included. And military radio (AFN) was still in the same dominant position… There were, however, the legendary V-Discs, which until then had been missing in Armstrong’s portfolio; and on some of those V-Discs there were, finally, real concerts with real audiences, a long way from the hasty collages which AFN had been practising on a broad scale since 1942, in an attempt to breathe a little life into what were basically just studio-sessions (cf. the notes to Vol. 10, which deal with their content: edits and mixes, introductions and music, interviews and laughter, not to mention canned applause…).

The most memorable of those real concerts – one of the most famous in jazz history – came on January 18th 1944 in a setting that was quite unusual: New York’s Metropolitan Opera, locally known as «The Met». In the course of the Thirties, jazz, of course, had «moved up in the world» with performances in such reputed venues as Carnegie Hall, but this wasn’t quite the same thing. Carnegie Hall, like the Royal Albert Hall in London or Salle Pleyel in Paris, was available for hire: anyone could play there if the place wasn’t already booked (finances permitting…). But a performer had to deserve The Met, and also had to be invited to play inside, as with other «regular» state-owned theatres. The fact that the early Forties were exceptional times had much to do with the fact that jazz was finally given the honour of being allowed inside this «temple» dedicated to the worship of «serious music».

Since 1936, two of the most widely-read music journals – in serious competition – were Metronome and Esquire, and they also organized annual polls, so that their readers could vote for the musicians who had been their favourites over the past year. Beginning with the 1938 referendum, it was decided that, at the end of the year in question (or early the year after), a few souvenir-records would be pressed by either RCA-Victor or Columbia, both of them heavyweight labels, and this practice continued until the Fifties. The results of those jam-sessions can be found on the CD Summit Meetings (Frémeaux FA 5050) which Pierre Lafargue compiled with his customary verve: it naturally includes some of the Esquire poll-winners in 1943 (cf. CD1, tracks 12-15), or at least, those winners who could get inside the studio that December 4th… On that occasion, RCA and Columbia, still non-starters due to the recording-ban, had to sit by and watch Milt Gabler’s young Commodore label step into the breach to run the session. Louis Armstrong was nowhere in sight for that one, probably because his greedy impresario Joe Glaser didn’t see any benefit to be had from his presence there. But it’s true that Roy Eldridge, Jack Teagarden and Barney Bigard weren’t there either, even though they were in the front row onstage at The Met the following month, rubbing shoulders with Louis, Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum, Al Casey, Oscar Pettiford, Sidney Catlett et al. The reverse was true for Cootie Williams and Edmund Hall – they were poll-winners, they’d been at the session on December 4th, and they didn’t play at The Met. There was one good thing about the referendum, however: for once, the votes weren’t cast by Esquire readers but by the period’s most famous critics and their like: Americans, of course, such as columnist Paul Eduard Smith, George Avakian, Bob Thiele, Barry Ulanov or John Hammond, but also a few foreigners (sometimes refugee foreigners) like Baron Timme Rosenkrantz, a Dane, the extremely British Leonard Feather (incidentally the organiser of the whole shebang), or Belgian poet Robert Goffin, one of the first writers to grace a page with words on the subject of jazz music – cf. Aux Frontières du Jazz, 1932; it was dedicated to Louis Armstrong – and then in the throes of writing a sentimental biography of his favourite trumpeter. Where were we? Ah, yes, critics and their like… They were sometimes reproached for being conservatives – they voted only for sure-fire established values – whereas America was brimming with talented youngsters. But things have to be seen in context: the concert at The Met was for «the war effort», and it had no vocation as a talent-spotter, however good the aforesaid youngsters might be… So, their time would come, never fear!

Two days before the great night, i.e. January 16th 1944, there was a programme on the radio to promote this exceptional concert (it was a show in the famous Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street series, produced first by NBC, then by ABC). For this «teaser», the line-up was the same – with the exception of Eldridge and Bigard – as the band heard by the lucky people who’d bought tickets for The Met. The three titles they played featuring Louis – Basin Street Blues, Esquire Blues and Honeysuckle Rose – appear on CD3 of Vol. 10 (tracks 15-17).

The legendary concert on January 18th was recorded entirely by AFRS, which produced several broadcasts that went out later; a powerful sponsor – a fizzy, alcohol-free soda with one of the most recognizable logos in the world – had part of the concert «on the air» at the same time (via ABC’s Blue Network) in the series entitled Victory Parade of Spotlight Bands. A few pieces (notably Basin Street Blues and Back O’ Town) were later released as V-Discs… They played almost thirty in all, beginning with Esquire Blues and ending (fittingly) with the national anthem. Satchmo appeared on thirteen of them, albeit sometimes so discreetly as to be almost inaudible. Not all of these were deemed necessary here, so we’ve included I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues, Back O’ Town Blues and Muskrat Ramble, the three tunes which show him at his best, together with the introduction of the musicians on Esquire Bounce… Listening to Coleman Hawkins playing along with all this brings a smile to your face, and he contributes to tunes which weren’t really his usual diet (in January ‘44 he was recording with Dizzy Gillespie!) The complete concert will no doubt be reissued by us in the near future, and it would be a good idea to include the takes from that January 16th broadcast where Louis was absent…

How about this, by the way: a small group with Louis Armstrong, Big T, Bigard, Big Sid Catlett… You’d only have to swap Tatum with Earl Hines and Pettiford with a young newcomer, and that would be it… These boys would go far very quickly. Watch this space…

A year later, minus one day – on January 17th 1945 to be precise – came the Second Esquire All American Jazz Concert, still based on critical opinion but conceived rather differently, as it involved poll-winners playing in places a long way apart: New Orleans’ Municipal Auditorium (with Louis, Bechet, James P. Johnson, Paul Barbarin); New York’s Blue Network studios (with Benny Goodman’s quintet and singer Mildred Bailey); and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium (with the Duke Ellington Orchestra). It seems that AFRS’s recording-machines were sulking over this daring «triplex» attempt, as they left the field wide open for ABC, which put out only excerpts – neither necessarily the best nor the most interesting! – from those three simultaneous concerts. They say, of course, that everything that was played in each venue was recorded, but as of today we still only have these brief fragments, and they hardly do justice to the scope of the event. On Basin Street Blues (CD3, track 3) for example, Armstrong swaps phrases with the man he said was his first master (before King Oliver), i.e. Willie “Bunk” Johnson (1879-1949), the cornet-player of his childhood and a man forgotten and then rediscovered by jazz archaeologists in the early Forties. Unfortunately, the piece we have lasts barely more than a minute… and then back to the main studio in NYC! Talk about missing a unique opportunity for the master to meet his pupil… Straining an ear lets you pick up a few notes on the cornet behind Louis’ vocal: good ol’ Bunk, no doubt. About the last piece, just after Leonard Feather’s introduction, we should be happily listening to that eminently Ellingtonian composition Things Ain’t What They Used to Be, played in convoy by the big band in California, the clarinettist from the core of the Big Apple, and the trumpeter somewhere down in the Bayou… But here again, things didn’t work out as planned and everything stops dead after two minutes… At least you can have a quick listen to Louis – not particularly sure of himself, by the way – playing a solo… Another missed opportunity, because Satchmo would never make a record with the large ducal outfit.

Another deception was the Tribute to Fats Waller from a February 11th 1945 broadcast on WNEW. Flanked by members of Fats Waller’s Rhythm (Herman Autrey, Gene Sedric, Al Casey…), Louis managed not to play a single composition by the Rabelaisian King of Stride Piano who sadly abandoned his admirers one deathly pale morning (December 15th 1943) at Kansas City’s railroad station. Armstrong thought him a “solid sender” and he knew those tunes really well; he’d even been the first to play a few of them, like Black and Blue, Sweet Savannah Sue, and especially Ain’t Misbehavin’! We’ve excluded these additional versions of On the Sunny Side and I Got Rhythm because the sound-quality of the recordings in our possession is, at best, merely average.

These memorable concerts aside, there was no lack of gigs for Armstrong in 1944-45: there were gigs at the Trianon Ballroom in Southgate, California for instance, and the Zanzibar Club in New York; he also played on military bases like Camp Reynolds (Pennsylvania), Tuskegee Army Airfield (Alabama) or Fort Huachuca (Arizona). During his stays out on the West Coast, Louis – he’d gone back to films in 1942 (Cabin in the Sky, cf. Vol. 10) after several years away from the projectors – received episodic film-offers in the spring and summer of 1944. In both cases he played opposite Dorothy Dandridge. The first film, Ray McCarey’s Atlantic City for the Republic studio, also brought in Paul Whiteman and his orchestra plus Buck and Bubbles. After a few notes at the end of Harlem on Parade (sung by Dorothy), Satchmo finally picks up Ain’t Misbehavin’ (as he ought to have done on the tribute to its composer!), slightly changes the lyrics, and then introduces the duettists (CD 1, track 22). The orchestra seen onscreen was indeed Armstrong’s band at the time, but it’s almost certain that the one hear is a different studio group !

The second film he appeared in was Vincent Sherman’s Warner Bros. picture Pillow to Post with the luminescent Ida Lupino, and it provides another song shared with Dorothy, Whatcha Say… A third film is sometimes mentioned, also produced by Warner in 1944 but this time with Delmer Daves directing: Hollywood Canteen, one of the many «All-Star» revues proposed between ‘42 and ‘45 by various studios as part of their own war effort. So this one was also a chance to see some of the studio’s stalwarts: Lupino, Eddie Cantor, Paul Henreid, Peter Lorre, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Dorothy Malone, Eleanor Parker, Roy Rogers, Barbara Stanwyck, Jane Wyman, Jack Benny, Jimmy Dorsey and his orchestra, Carmen Cavallaro, The Andrews Sisters… But no Armstrong. Or at least, not in the copies we’ve seen. Did it have a scene with Armstrong that was cut from the final edit, as per Doctor Rhythm in 1938? Hardly likely.

On August 9th 1944, two months and three days after the landing in Normandy, with war still raging in Europe, Louis was reunited with the Decca studios in Los Angeles after more than two years’ absence. He cut a version for record of Whatcha Say (different from the film-soundtrack, but still with Dorothy Dandridge), and also two other sides, Groovin’ and Baby Don’t You Cry. All three would remain unreleased for several years… On the other hand, the two new pieces which inaugurated his studio-work on January 14th 1945 – Jodie Man and I Wonder, featuring Satchmo with a studio pick-up group – were quickly made available to his fans, including those in Europe. Their quick release probably aimed to show that (almost) everything had now gone back to normal…

The reality was that, in August 1944, the ban on so-called commercial recordings was still in force, but it had evolved since the previous November: from August 1st 1942 until that November, the ban had been total: it applied to every label – big or small, old or new – in a country where devious workarounds were hardly easy. The big, old-established firms took advantage of the ban to reissue records and publish tracks that had been archived earlier. Those with nothing to reissue, and even fewer archives, just had to grin and bear it, doing what they could. By the end of ‘43 the situation was untenable, and the smaller producers accepted the conditions imposed by the musicians’ syndicate; they subsequently went back to business. By December, Signature, the label founded by Bob Thiele in 1940, had already recorded some superb sides by Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Dicky Wells, Barney Bigard et al… Keynote, Blue Note, Allegro, Apollo and other labels did likewise. The only «big» label to follow suit was Decca (although its foundation was recent). And that’s how a few celebrities, Armstrong among them, returned to recording as early as the spring of 1944. The two mammoths, however – RCA and Columbia – would have nothing to do with it, and the result was that the ban continued to apply to just those two labels… All things come to an end, however, and the ban was over (even for them) on November 11th 1944. Maybe the Armistice had something to do with it…

The whole embargo, of course, applied only to records intended for sale to the public; the ban didn’t concern recordings made for radio or films, nor did it apply to the legendary series of 12» 78s known as V-Discs (the «V» stood for «Victory»): 905 different platters were put into circulation between October 1943 and May 1949, with total pressings of more than eight million copies, most of which were stamped on a kind of primitive vinyl.

The heart of the V-Disc enterprise was situated in New York – unlike AFRS which was based in Los Angeles – under the direction of one Lieutenant George Robert Vincent (a veteran who’d worked with the Edison company), and things really started humming in the summer of 1943. The people behind V-Disc – Steve Sholes, Morty Palitz, Walt Heebner, Tony Janak and a few others – had all worked (as civilians) in studios making records or producing radio programmes, and some of them returned to their former occupations after the war. Unlike the transcriptions which were made for radio (military or not), and which were delivered exclusively to radio-stations expected to play them over the air, the V-Discs were regularly shipped to GIs and other soldiers (even on the field of battle) who played them when they weren’t otherwise occupied. In 1944-45 they were being sent out at a rate of a box of thirty discs per month, and there were two distinct series with different catalogue-numbers, one larger series destined for the Army and the other for the Navy. To build its catalogue, the V-Disc team eagerly cast its net to cover all possible sources of material: recordings (more or less recent) on loan from record-companies (we know of some Ellington material dating from 1930!), plus fragments of concerts and radio-shows (both AFN and transcriptions from commercial networks), film-soundtracks etc. And above all there were special V-Disc sessions; these were held regularly from autumn 1943 onwards, particularly for RCA and NBC. One of the first to turn up to the studio – in mid-september – was Fats Waller; it was his last recording-session…

Jazz, in the broad sense, (i.e., bands and musicians who were white!), made up around one third of the V-Disc repertoire, but some people, like Ellington, never did a dedicated V-Disc session, even though he was well-represented in the series. Basie, on the other hand, did a lot of them. As for Satchmo, he contented himself with playing on the December 6th and 7th 1944 session which was divided into V-Disc All Star Jam Session and Louis Armstrong and the V-Disc All Stars; they represented only two titles, but each had two «takes»: the ones released at the time can be heard on tracks 18 and 19 on CD2 here, where Louis and Teagarden seem to be enjoying each other’s company again hugely. They even proved it by giving their joint composition the title Jack–Armstrong Blues. It was another hint at what would happen later…

On all the above – except for the brief Atlantic City interlude on film and his return to Decca on August 9th ‘44 – Armstrong scarcely recorded with his regular band apart from the AFRS transcriptions, but the group was present on most of his club bookings. The line-up changed again between the end of 1943 and the early months of ‘44. It’s not really known why people like Bernard Flood (tp), Henderson Chambers (tb), or especially Joe Garland, the saxophonist who replaced Luis Russell as musical director, left Satchmo at this time: the suspicion, obviously, is that Joe Glaser showed them the door without any qualms. Whatever… When the time came for the concert at The Met, another tenor-player, Teddy McRae, inherited Garland’s role and he was tasked with getting a new group together. This was the band – more or less – heard on radio between ‘44 and ‘45. After a year’s absence, Velma Middleton, the plump singer/dancer, was back in the fold, and she stayed until 1947. As for the trumpeter climbing into the upper register, this was probably Andrew “Fatso” Ford, to whom Louis gladly left the exercises that no longer tempted him. Trumpeter Irakli de Davrichewy, known as the French Satchmo – as a jazz historian, he probably knows more about Armstrong than anyone, and even plays like Louis would have (if he’d been born in France) – observed that his hero «Pops» didn’t really care for the jagged swing performances which contemporary audiences liked so much, and which he couldn’t avoid putting in his repertoire; Satchmo in fact preferred things that were much calmer, more «settled» as it were, because they were more likely to turn into something approaching majesty…

In the 1944 band, an honest if unsurprising group, the presence of one musician, however, is worthy of attention. He played tenor from mid-May to mid-September – at least McRae accepted him! –, he was 21 years old, and people predicted he’d have an exciting future: Dexter Gordon. You can hear him playing with all the fire of his tender years on three versions of Ain’t Misbehavin’, two versions of Keep On Jumpin’, plus Stompin’ at the Savoy, King Porter Stomp and Perdido (spread over CD1 and CD2). Louis, who often calls out to him – “Brother Dexter!” – when it’s his turn to solo, had taken a liking to him years earlier during his first stay out on the West Coast, in the same way as he took a shine to the young drummer to whom he gave a chance to play vibraphone: Lionel Hampton… In September ‘44 Dexter joined singer Billy Eckstine’s band.

As for the rest, it’s to be noted that in 44/45, the two AFRS collections where Louis Armstrong was most often to be found previously, Jubilee and Downbeat, gave way to the Victory Parade of Spotlight Bands series (see above, the collection ABC shared with Coca Cola if you hadn’t guessed) and the One Night Stand collection (a series aimed at «hot» dancers)… Some of them are known to be missing, notably Victory Parade 277 (February 5th 1944) and 319 (dated March 25th). And, as previously, care has to be taken here because it’s possible to find the same tune (in the same version) on several of these big records released on different dates, sometimes eight months apart. But on the other hand, the versions can be different, too! (cf. liner notes, Vol. 10). A good example of the diabolical confusion that’s possible concerns the recordings made at the Zanzibar Club in New York between December ‘44 and March ‘45: there are at least three versions of Accentuate the Positive, a piece that Louis used to play every night at the time. They appear on three different transcriptions but manifestly come from the same source. The third of these versions (not reproduced here) was even included on the AFRS “New Year” volume broadcast on December 31st 1945 – along with sixteen other tunes by other artists – some nine months after it was actually played…

Most of the difficulties, of course, are due to the passably repetitive repertoire which, as usual, contains the familiar – but always pleasant to listen to – bunch of tunes like Basin Street Blues, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Confessin’, Ain’t Misbehavin’, On the Sunny Side of the Street, King Porter Stomp, the inevitable Brother Bill, Lazy River, Perdido, and let’s not forget the signature-tune When It’s Sleepy Time… However, we can be sure that all the versions of these pieces which you can listen to here (in addition to the versions of more recent themes such as Blues in the Night, Groovin’, Keep on Jumpin’, I Lost my Sugar in Salt Lake City, Accentuate…) are different from each other and/or those pieces contained in Vol. 10 of the present collection. Note also that, among all these, you occasionally come across pieces which Armstrong only rarely recorded for commercial purposes or didn’t record at all: A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody, Solid Sam, Louise, Going My Way (taking his hat off to his pal Bing Crosby for his Oscar), Swanee River, Swingin’ on a Star, Always, It’s Love, Love, Love, Stompin’ at the Savoy, Don’t Sweetheart Me… Most of them are naturally little more than ephemeral ditties but, with Louis Armstrong at the helm, you only wish there were more of them… Take the AFRS Spotlight Bands N° 503 – forty centimeters (16 inches) squeezed into Charles Delaunay’s collection – which proposes versions of Louise, Lazy River, Is You Is or Is You Ain’t my Baby, Groovin’, as well as an I Walk Alone without Louis. The atrocious state of decomposition of this «thing» hardly encouraged the inclusion of these pieces here, as countless other very similar variations exist already, all probably from the same series (plural) of recordings. All except Dance with the Dolly, that is, which Satchmo seems to have done only once; there’s no trace of another one in his discography, in any case. Why hesitate? We’ve included it on CD2 (track 16) despite the raging storm soaking this poor little rag doll to the skin. Rag or ragtime?! But Louis Armstrong was well worth it.

Adapted by Martin Davies from the french text by Daniel Nevers

© 2012 Frémeaux & Associés - Groupe Frémeaux Colombini

DISQUE / DISC 1

ESQUIRE ALL-AMERICAN JAZZ CONCERT

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo); Roy ELDRIDGE (tp); Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, vo); “Barney” BIGARD (cl); Coleman HAWKINS (ts); Art TATUM (p); Al CASEY (g); Oscar PETTIFORD (b); Sidney CATLETT (dm).

New York City (Metropolitan Opera House), 18/01/1944

1. Presentation & ESQUIRE BOUNCE (L. Feather)

(ABC Transcription) 3’24

2. I GOTTA RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES (McHugh-Fields)

(ABC Transcription) 3’44

3. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L. Armstrong-L. Russell)

(ABC Transcription) 3’35

4. MUSKRAT RAMBLE (Ed. Ory) (ABC Transcription) 2’17

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo) & (poss.) Jesse BROWN, Thomas GRIDER, Lester CURRANT, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp); Taswell BAIRD, Larry ANDERSON, Adam MARTIN (tb); John BROWN, Willard BROWN (as); Dexter GORDON (ts); Teddy McRAE (ts, cond); Ernest THOMPSON (bar.s); Ed SWANSTON (p); Emmett SLAY (g); Alfred MOORE (b); James “Coatsville” HARRIS (dm). Los Angeles, ca. 05/1944

Selon certaines sources, il s’agit d’une formation de studio et non de l’orchestre régulier / According to some sources this band is not the regular one but a studio group.

5. LAZY RIVER (H. Carmichael-S. Arodin) (AFRS “Command Performance” n°120) 4’11

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 5 / Personnel as for 5. Plus Velma MIDDLETON (vo).

Los Angeles (ABC Studios), ca. 19 & 20/05/1944

6. Presentation & AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T.W. Waller-A. Razaf) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240) 4’25

7. I LOST MY SUGAR IN SALT LAKE CITY (L. René-J. Lange) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240 & 253) 3’10

8. A PRETTY GIRL IS LIKE A MELODY (I. Berlin) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240 & 253) 3’08

9. SWANEE RIVER (Trad.) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240 & 253) 3’10

10. BABY DON’T YOU CRY (Anonymous) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240 & 253) 4’12

11. DON’T SWEETHEART ME (Smith-Brown-Gill) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240 & 253) 2’45

12. GROOVIN’ (McRae-O’Nan-Brown) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°240) 0’52

13. EASY AS YOU GO (L. René-O. René) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°253) 2’53

14. I COULDN’T SLEEP A WINK LAST NIGHT (Hudson-DeLange) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°253) 2’51

15. KEEP ON JUMPIN’ (L. Russell) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°253) 3’34

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 6 à 15 / Personnel as for 6 to 15.

(Broadcast). South Gate (Ca.) (Trianon Ballroom),10-26/05/1944

16. NO LOVE, NO NOTHING (H. Warren-L. Robin) 2’34

17. IS MY BABY BLUE TONIGHT? (L. Ward-S. Caplin) 2’17

18. BLUES IN THE NIGHT (H. Arlen-J. Mercer) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°253) 3’17

19. KEEP ON JUMPIN’ (L. Russell) 3’22

20. STOMPIN’ AT THE SAVOY (E. Sampson-C. Webb-B. Goodman-A. Razaf) 2’40

21. SOLID SAM (T. McRae) 2’38

LOUIS ARMSTRONG, DOROTHY DANDRIDGE & Studio Orchestra

L.ARMSTRONG (tp, vo) & Dorothy DANDRIDGE (vo); Orch.; Walter SCHARF (cond). Bande-son du film / Soundtrack of: “Atlantic City” (Republic). Hollywood, 05-06/1944

22. HARLEM ON PARADE (H. Arlen-J. Mercer) 1’25

& AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T. Waller-A. Razaf) 2’25

DOROTHY DANDRIDGE & LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

D.DANDRIDGE (vo), L.ARMSTRONG & formation comme pour 5/personnel as for 5. Bande-son du film / Soundtrack of: “Pillow to Post” (Warner). Hollywood, 08/1944

23. WHATCHA SAY? (Lane-T. Koehler) 1’35

DISQUE / DISC 2

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp,vo); Jesse BROWN, Thomas GRIDER, Lester CURRANT, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp); Taswell BAIRD, Adam MARTIN, Larry ANDERSON (tb); John BROWN, Willard BROWN (as); Dexter GORDON (ts); Teddy McRAE (ts, cond); Ernest THOMPSON (bar.s); Ed SWANSTON (p); Emmett SLAY (g); Alfred MOORE (b); James HARRIS (dm); Dorothy DANDRIDGE (vo). Los Angeles, 9/08/1944

1. WHATCHA SAY? (Lane-T. Koehler)

(Decca test /mx. DLA3502-B) 3’02

2. GROOVIN’ (T. McRae-F. Brown-R. I. O’Nan)

(Decca test /mx. DLA3500-A) 2’49

3. BABY DON’T YOU CRY (Anonymous)

(Decca test /mx. DLA3501-A) 2’53

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Formation comme pour 1 à 3 / Personnel as for 1 to 3. Moins/minus D.DANDRIDGE.

Stockton Fields (Ca.), 06/1944

4. KING PORTER STOMP (F. Morton) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°382) 2’42

5. IT’S LOVE, LOVE, LOVE (Arlen-Koehler) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°382) 2’10

6. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T. Waller-A. Razaf) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°382) 3’03

Même formation / Same personnel. Plus Velma MIDDLETON (vo). Fort Huachuca (Ariz.), 08/1944

7. LOUISE (R.A. Whiting-L. Robin) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°444) 2’30

8. GOIN’ MY WAY (Van Heussen-Burke) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°444) 2’33

9. GROOVIN’ (T. McRae-F. Brown-R. O’Nan) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°444) 2’27

10. IS YOU IS OR IS YOU AIN’T MY BABY? (G. Arnheim-G. Tobias) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°444) 2’47

Même formation / Same personnel. Camp Reynolds (Penn.), ca. 3-5/09/1944

11. PERDIDO (J. Tizol) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°465) 2’31

12. AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (T. Waller-A. Razaf) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°465) 3’11

Même formation / Same personnel. Moins / minus Dexter GORDON.

Tuskegee Army Airfield (Alabama), ca. 6/10/1944

13. KEEP ON JUMPIN’ (L. Russell) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°486) 3’10

14. SWINGIN’ ON A STAR (Van Heusen-Burke) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°486) 2’17

15. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) & Theme (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°486) 3’26

Formation comme pour 13 à 15 / Personnel as for 13 to 15. Unknown location (Texas), ca. 15/10/1944

16. DANCE WITH THE DOLLY (Anonymous) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°503) 2’52

V-DISC ALL STAR JAM SESSION (17 & 18)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE V-DISC ALL STARS (19 & 20)

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo) ; Bobby HACKETT (cnt) ; Jack TEAGARDEN (tb, vo) ; Ernie CACERES (cl) ; Nick CAIAZZA (ts) ; Johnny GUARNIERI (p) ; Herb ELLIS (g) ; Al HALL (b) ; WILLIAM “Cozy” COLE (dm), Plus Billy BUTTERFIELD (tp) & Lou McGARITY (tb), sur/on 17 & 18.

New York City (NBC Studios, Rockefeller Center), 7/12/1944

17. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES (L. Armstrong-J. Teagarden) (V-Disc test/safety) 4’57

18. JACK-ARMSTRONG BLUES (L. Armstrong-J. Teagarden) (V-Disc 384 & 164/mx.VP 1054-D4-TC 540-1) 3’35

19. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Reynolds-Dougherty)

(V-Disc 491/mx. VP 1079-D4-TC 558-1) 3’12

20. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Reynolds-Dougherty)

(V-Disc test/safety) 3’15

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo); Billy BUTTERFIELD (tp); Sid STONEBURN, Jules RUBIN (as); Bill STEGMEYER (cl, ts); Arthur ROLLINI (ts); Paul RICCI (bar.s); Dave BOWMAN (p); Carl KREISS (g); Bob HAGGART (b); Johnny BLOWERS (dm). New York City, 14/01/1945

21. JODIE MAN (D. Fisher-A. Roberts)

(Decca BM 03595/mx. 72692-A) 3’15

22. I WONDER (R. Leween-C. Gant)

(Decca BM 03595/mx. 72693-A) 3’00

DISQUE / DISC 3

SECOND ESQUIRE ALL AMERICAN JAZZ CONCERT

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo); J.C. HIGGINBOTHAM (tb); Sidney BECHET (cl, ss); James P. JOHNSON (p); Richard ALEXIS (b); Paul BARBARIN (dm), plus Willie “Bunk” JOHNSON (tp, sur/on 3).

New Orleans, La (Municipal Auditorium), 17/01/1945

1. Presentation & CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds)

(ABC Transcription) 6’10

2. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L. Armstrong-L. Russell)

(ABC Transcription) 2’30

3. BASIN STREET BLUES (S. Williams)

(ABC Transcription) 1’03

Même formation / Same personnel. Plus Benny GOODMAN (cl), à/in New York & Duke ELLINGTON and His Orchestra, à/in Los Angeles. 17/01/1945

4. THINGS AIN’T WHAT THEY USED TO BE (E.K. & M. Ellington) (ABC Transcription) 2’11

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo); Jesse BROWN, Thomas GRIDER, Ludwig JORDAN, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp); Norman POWE, Adam MARTIN, Larry ANDERSON, Russell “Big Chief” MOORE (tb); John BROWN, Joe EVANS (as); Eddie “Lockjaw” DAVIS (ts); Teddy McRAE (ts, cond); Ernest THOMPSON (bar.s); Ed SWANSTON (p); Elmer WARNER (g); Alfred MOORE (b); James HARRIS (dm); Velma MIDDLETON (vo).

New York City (New Zanzibar Club), 13 & 20/02/1945

5. Theme & Presentation & ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J. McHugh-D. Fields)

(AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 4’20

6. ACCENTUATE THE POSITIVE (H. Arlen-J. Mercer) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 4’27

7. I CAN’T GIVE YOU ANYTHING BUT LOVE (J. McHugh-D. Fields) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 2’40

8. ALWAYS (I. Berlin) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 3’00

9. IT AIN’T ME (Davis-Palmer) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 3’05

10. CONFESSIN’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) (AFRS “One Night Stand” n°540) 3’35

& BLAME IT ON ME (Van Heusen-Burke) 1’20

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis ARMSTRONG (tp, vo), (prob.) Robert BUTLER, Ludwig JORDAN, Lewis VANN, Andrew “Fatso” FORD (tp); Norman POWE, Adam MARTIN, Larry ANDERSON, Russell “Big Chief” MOORE (tb); Arthur DENNIS, Don HILL (as); Joe GARLAND, Milt THOMAS (ts); Ed SWANSTON (p); Elmer WARNER (g); Alfred MOORE (b); James HARRIS (dm). South Gate (Ca.)(Trianon Ballroom), 08/1945

11. Theme & IT AIN’T ME (Davis-Palmer) (AFRS “Magic Carpet” n°101) 3’46

12. CALDONIA (F. Moore) & Theme (AFRS “Magic Carpet” n°101) 3’00

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Prob. même formation que pour 11 & 12 / Prob. personnel as for 11 & 12. Plus Ella Mae MORSE (vo sur/on 15) & Frank SINATRA (vo sur/on 17); Ernie “Bubbles” WHITMAN (mc).

Los Angeles (NBC Studios), 08-09/1945

13. Theme & Presentation (AFRS “Jubilee” n°146) 1’50

14. ACCENTUATE THE POSITIVE (H. Arlen-J. Mercer) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°146) 4’55

15. ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET (J. McHugh-D. Fields) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°146) 3’15

16. I WONDER (R. Leween-C. Gant) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°146) 3’35

17. BLUE SKIES (I. Berlin) (AFRS “Jubilee” n°146) 2’12

& Theme (One O’ Clock Jump) (W. Basie) 1’10

NOTE : Accentuate the Positive (14) provient peut-être d’un enregistrement plus ancien, effectué au “Club Zanzibar” de New York au printemps 1945.

Accentuate the positive (14) may be derived from an earlier recording from the “Club Zanzibar” in New York in the spring of 1945.

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Prob. même formation que pour 16 & 17 / Prob. personnel as for

16 & 17. Spokane (Geiger Field), Washington, ca. 10/1945

18. BACK O’ TOWN BLUES (L. Armstrong-L. Russell)

(AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°762) 3’35

19. ME AND BROTHER BILL (L. Armstrong)

(AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°762) 2’42

20. PERDIDO (J. Tizol) (AFRS “Spotlight Bands” n°762) 2’45

«?Vous savez, on ne peut rien jouer à la trompette que Louis Armstrong n’ait déjà fait – y compris le moderne. J’aime sa conception du jeu de la trompette, jamais il ne sonne mal. Il joue sur le temps. On ne peut pas mal jouer quand on joue sur le temps et avec un tel feeling?»

Miles DAVIS

“You can’t play nothing on trumpet that doesn’t come from him, not even modern shit. I can’t ever remember a time when he sounded bad. Never. Not even one time. He had great feeling up in his trumpet and he always played on the beat. I always just loved the way he played and sang.” Miles DAVIS

Les intégrales Frémeaux & Associés réunissent généralement la totalité des enregistrements phonographiques originaux disponibles ainsi que la majorité des documents radiophoniques existants afin de présenter la production d’un artiste de façon exhaustive.

L’Intégrale Louis Armstrong déroge à cette règle en proposant la sélection la plus complète jamais éditée de l’œuvre du géant de la musique américaine du XXe siècle, mais en ne prétendant pas réunir l’intégralité de l’œuvre enregistrée.

CD INTEGRALE LOUIS ARMSTRONG VOLUME 11 JACK - ARMSTRONG BLUES 1944-1945, LOUIS ARMSTRONG © Frémeaux & Associés 2012 (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)