- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

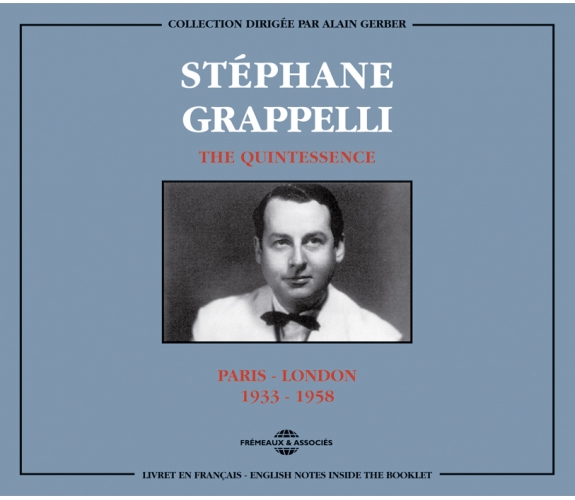

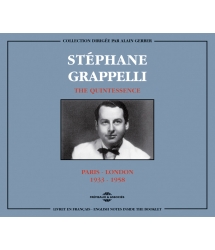

PARIS - LONDON 1933-1958

Ref.: FA281

EAN : 3448960228121

Artistic Direction : DANIEL NEVERS

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 17 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

PARIS - LONDON 1933-1958

PARIS - LONDON 1933-1958

“It really annoys me when people ask if I was Django Reinhardt's violinist. I tend to answer, ‘No, it was Django who was my guitarist!’ But I always add, 'the greatest guitarist of all time!” Stéphane GRAPPELLI

Frémeaux & Associés’ « Quintessence » products have undergone an analogical and digital restoration process which is recognized throughout the world. Each 2 CD set edition includes liner notes in English as well as a guarantee. This 2 CD set present a selection of the best recordings by Stephane Grappelli between 1933 and 1958.

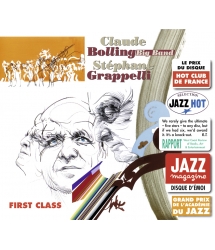

FIRST CLASS

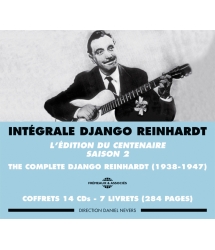

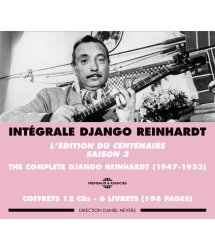

THE COMPLETE WORKS 1947-1953

THE COMPLETE WORKS 1938-1947

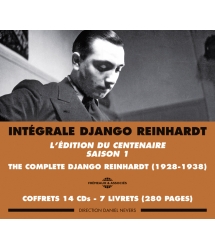

THE COMPLETE WORKS 1928-1938

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Fits As A FiddleGrégor & ses Grégoriens00:03:161933

-

2Chinatown, My ChinatownQuintette du Hot Club de France00:02:521935

-

3DaphneStéphane Grappelly, Eddie South & Django Reinhardt00:03:071937

-

4You Took Advantage Of MeStéphane Grappelly, Michel Warlop & Django Reinhardt00:03:001937

-

5I'Ve Found A New BabyStéphane Grappelly & Django Reinhardt00:02:411937

-

6Je veux ce soirJean-Fred Mêlé & le Jazz Swing Zeppilli00:03:071937

-

7I Cried For YouArthur Young & Hatchet's Swingtette00:03:031940

-

8In The MoodArthur Young & Hatchet's Swingtette00:03:021940

-

9How Am I To KnowArthur Young & Hatchet's Swingtette00:02:551940

-

10Twelfth Street RagArthur Young & Hatchet's Swingtette00:02:561940

-

11I Never KnewStéphane Grappelly & His Orchestra00:02:361941

-

12Tiger RagStéphane Grappelly & His Orchestra00:02:331941

-

13Stephan's BluesStéphane Grappelly & His Orchestra00:03:221941

-

14Some Of These DaysWitley Court Music Box00:02:411941

-

15Blue SkiesWitley Court Music Box00:03:021941

-

16From The Top Of Your HeadWitley Court Music Box00:02:321941

-

17I Got Rhythm'Witley Court Music Box00:02:421941

-

18Crazy Rhythm'Witley Court Music Box00:02:351941

-

19The Folks Who Live On The HillStéphane Grappelly & His Quintet/Orchestra00:03:291942

-

20Star DustStéphane Grappelly & His Quintet/Orchestra00:03:301943

-

21Heavenly MusicStéphane Grappelly & His Quintet/Orchestra00:03:061943

-

22Out Of NowhereStéphane Grappelly & His Quintet/Orchestra00:03:191945

-

23Embraceable YouQuintette du Hot Club de France00:03:081946

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Oui, pour vous revoirStéphane Grappelly's Hot Four00:02:431947

-

2Tea For TwoStéphane Grappelly00:03:121947

-

3Old Man RiverQuintette du Hot Club de France00:03:431947

-

4Pennie From HeavenJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:02:111947

-

5Can'T Help Loving That ManJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:03:551954

-

6A Girl In CalicoJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:02:201954

-

7The World Is Waiting For The SunriseJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:02:101954

-

8I Can't Recognize The TuneJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:03:291954

-

9Looking At YouJack Dévial & Stéphane Grappelly00:02:091954

-

10Swing 39Henri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:03:011954

-

11BellevilleHenri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:03:001954

-

12Manoir de mes rêvesHenri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:03:521954

-

13DjangologyHenri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:02:461954

-

14Alembert'sHenri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:02:421954

-

15MarnoHenri Crolla - Stéphane Grappelly Quartet00:03:331954

-

16S'WonderfulStéphane Grappelly Quartet00:02:301954

-

17Someone To Watch Over MeStéphane Grappelly Quartet00:02:571956

-

18NuagesStéphane Grappelly & son grand orchestre à cordes00:02:471956

-

19ManhattanEddie Barclay & son Orchestre00:02:231957

-

20Tu joues avec le feuEddie Barclay & son Orchestre00:02:591957

-

21Minor SwingHenri Crolla All Stars00:03:411958

-

22Swing 42Henri Crolla All Stars00:03:011958

-

23Place de Brouckère Notre ami DjangoHenri Crolla All Stars00:03:301958

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLI

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLI

THE QUINTESSENCE

PARIS - LONDON 1933 - 1958

DISCOGRAPHIE / DISCOGRAPHY

CD 1 (1933-1946)

1. FIT AS A FIDDLE (Ultraphone AP 1005/mx. P 76362) 3’15

GRÉGOR ET SES GRÉGORIENS : Gaston Lapeyronnie, Pierre Allier (tp) ; Jean Naudin, Vladimir (tb) ; André Ekyan, Roger Fisbach ou/or Georges Tharaud (as) ; André Lamory, Alix Combelle (ts) ; Roger Allier (bsx) ; Michel Warlop (vln) ; Stéphane Grappelli (vln solo, p) ; Michel Emer (p, arr) ; Émile Feldman (g) ; Roger “Toto” Grasset (b) ; McGregor (dm) ; Grégor (Krikor Kelekian) (dir). Paris, ca. 20-25/03/1933.

2. CHINATOWN, MY CHINATOWN (Decca test /mx. 2037 HPP) 2’49

QUINTETTE DU HOT CLUB DE FRANCE : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Django Reinhardt (g solo) ; Joseph Reinhardt, Pierre “Baro” Ferret (g) ; Louis Vola (b). Paris, 13/10/1935.

3. DAPHNÉ (Swing SW 12/mx. 0LA 2149-1) 3’04

DUO DE VIOLONS : Eddie South, Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Django Reinhardt (g solo) ; Roger Chaput (g) ; Wilson Myers (b). Paris, 29/09/1937.

4. YOU TOOK ADVANTAGE OF ME (Swing SW 74/mx. 0LA 2150-1) 2’57

MICHEL WARLOP & STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY (vln), acc. par/by Roger Chaput & Django Reinhardt (g). Paris, 29/09/1937.

5. I’VE FOUND A NEW BABY (Swing SW 21/mx. 0LA 1738-2) 2’40

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY (vln solo), acc. par/by Django Reinhardt (g). Paris, 29/09/1937.

6. JE VEUX CE SOIR (Polydor 512990/mx. 3937½ HPP) 3’01

JEAN-FRED MÊLÉ, acc. par le Jazz Swing Zeppilli : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Pierre Zeppilli (p) ; Joseph Reinhardt, Eugène Vèes (g) ; Louis Vola (b) ; Jean-Fred Mêlé (voc). Paris, 9/12/1937.

7. I CRIED FOR YOU (Decca F.7644/mx. DR 4353-1) 3’00

ARTHUR YOUNG & HATCHETT’S QUARTET : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Arthur Young (novachord, ldr) ; Frank Baron (p) ; Tony Spurgin (dm) ; Beryl Davis (voc). London, 24/02/1940.

8. IN THE MOOD (Decca F.7450/mx. DR 4428-2) 3’01

9. HOW AM I TO KNOW ? (Decca F.7624/mx. DR 4581-1) 2’54

ARTHUR YOUNG & HATCHETT’S SWINGTETTE : Stan Andrews (tp, cl, vln) ; Dennis Moonan (ts, vla) ; Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Arthur Young (novachord, ldr) ; Frank Baron (p) ; Jack Llewellyn, Noël “Chappie” d’Amato (g) ; George Senior (b) ; Tony Spurgin (dm) ; Beryl Davis & Trio (voc). London, 19/03 & 19/04/1940.

10. TWELFTH STREET RAG (Decca F.7697/mx. DR 5117-1) 2’55

HATCHETT’S SWINGTETTE : Formation comme pour 8 & 9 / Personnel as for 8 & 9. Moins/minus A. Young & B. Davis. London, 19/11/1940.

11. I NEVER KNEW (Decca F.8128/mx. DR 4902-3) 2’33

12. TIGER RAG(Decca F.7787/mx. DR 5404-2) 2’31

13. STEPHANE’S BLUES (Decca F.7787/mx. DR 5405-2) 3’20

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY And His MUSICIANS : Stéphane Grappelli (vln, ldr) ; Dennis Moonan (vln, as) ; Stan Andrews, Eugene Pini (vln) ; Non Identifié/Unidentified (vlc/cello) ; George Shearing (p, arr) ; Syd Jacobson (g) ; George Gibbs (b) ; Harry Chapman (harp) ; Jock Jacobson (dm) Reg Conroy (vib). London, 28/02/1941.

14. SOME OF THESE DAYS (Special JH-38/mx. CTP 11733-1) 2’39

15. BLUE SKIES (Special JH-39/mx. CTP 11734-1) 2’59

16. FROM THE TOP OF YOUR HEAD (Special JH-39/mx. CTP 11735-1) 2’29

17. I GOT RHYTHM (Special JH-37/mx. CTP 11737-1) 2’39

18. CRAZY RHYTHM (Special JH-37/mx. CTP 11738-1) 2’34

WITLEY COURT MUSIC BOX : W.O. Davison (as) ; Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; E. Farrar ou/or J. Hegarty (p) ; Noël “Chappie” d’Amato (g) ; Bert Howard (b) ; Joyce Head (voc). London, 18/03/1941.

19. THE FOLKS WHO LIVE ON THE HILL (Decca F.8204/mx. DR 6933-2) 3’27

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY And His QUINTET : Stéphane Grappelli (vln, ldr) ; Pat Dodd (p) ; Noël “Chappie” d’Amato, Joe Deniz (g) ; Tommy Brownley (b) ; Dave Fullerton (dm, vib, voc). London,20/08/1942.

20. STAR DUST (Decca F.8451/mx. DR 7189-2) 3’28

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY And His QUINTET : Formation comme pour 19 / Personnel as for 19. George Shearing (p) remplace/replaces Dodd. Plus Dennis Moonan (as, bars). London, 21/01/1943.

21. HEAVENLY MUSIC (Decca F.8375/mx. DR 7729-2) 3’03

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY And His QUINTET : Stéphane Grappelli (vln, ldr) ; George Shearing (p) ; Alan Mindell, poss. Joe Deniz (g) ; poss. Joe Nussbaum (b) ; Dave Fullerton (dm) ; Beryl Davis (voc). London, 6/10/1943.

22. OUT OF NOWHERE (Decca F.8582/mx. DR 9763-1) 3’18

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY And His ORCHESTRA : Stéphane Grappelli (vln ldr) ; Non Identifiés/Unidentified (cordes/strings) ; George Shearing (p) ; George Elliott (g) ; Peter Akister (b) ; Jack Parnell (dm) ; Doreen Henry (voc). London, 25/10/1945.

23. EMBRACEABLE YOU (Swing SW 229/mx. CM 243-1 [0EF 27-1]) 3’06

DJANGO REINHARDT & le QUINTETTE DU HOT CLUB DE FRANCE avec STEPHANE GRAPPELLY : Stéphane Grappelli (vln, arr) ; Django Reinhardt (g solo, arr) ; Jack Llewellyn, Allan Hodgkiss (g) ; Coleridge Goode (b). London 31/01/1946.

CD 2 (1947-1958)

1. OUI, POUR VOUS REVOIR (Swing SW 271/mx. 0SW 478-1) 2’41

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY’S HOT FOUR : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Roger Chaput, Joseph Reinhardt (g) ; Emmanuel Soudieux (b). Paris, 17/10/1947.

2. TEA FOR TWO (Swing SW 271/mx. 0SW 481-1) 3’06

STEPHANE GRAPPELLY, piano solo. Paris, 17/10/1947.

3. OL’ MAN RIVER (Radio Diffusion Française/Broadcast) 3’37

DJANGO REINHARDT & STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY dans “SURPRISE-PARTIE” : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Django Reinhardt (g solo) ; Joseph Reinhardt, Eugène Vèes (g) ; Fred Ermelin (b). Paris, 21/11/1947.

4. PENNIE FROM HEAVEN (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 232a) 2’10

5. CAN’T HELP LOVIN’ THAT MAN (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 232b) 3’50

6. A GIRL IN CALICO (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 232c) 2’19

7. THE WORLD IS WAITING FOR (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 232d) 2’06 THE SUNRISE

8. I CAN’T RECOGNIZE THE TUNE (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 233a) 3’30

9. LOOKING AT YOU (VSM FFLP 1042/mx. 0XLA 233d) 2’05

JACK DIÉVAL avec STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY (Jazz aux Champs-Elysées n°2) : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Jack Diéval (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm). Paris, 17/09/1954.

10. SWING 39 (Duc-Thomson 250 V 004/mx.LD 372a) 2’57

11. BELLEVILLE (Duc-Thomson 250 V 004/mx.LD 372b) 2’56

12. MANOIR DE MES RÊVES (Duc-Thomson 250 V 004/mx.LD 373a) 3’50

13. DJANGOLOGY (Duc-Thomson 250 V 004/mx. LD 373b) 2’42

14. ALEMBERT’S (Duc-Thomson 250 V 005/mx. D 45-282) 2’38

15. MARNO (Duc-Thomson 260 V 044) 3’30

HENRI CROLLA - STÉPHANE GRAPPELLI QUARTET : Stéphane Grappelli (vln, p sur/on 15) ; Henri Crolla (g) ; Emmanuel Soudieux (b) ; Baptiste “Mac Kac” Reilles (dm). Paris, 30/12/1954.

16. S’WONDERFUL (Barclay 84034/mx. 7Bar 30234) 2’28

17. SOMEONE TO WATCH OVER ME (Barclay 84034) 2’56

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY QUARTET : Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; Maurice Vander (p, clavecin/harpsichord sur/on 17) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Baptiste “Mac Kac” Reilles (dm). Paris, 6 & 14/02/1956.

18. NUAGES (Barclay 82083) 2’45

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLY & son GRAND ORCHESTRE à CORDES : Stéphane Grappelli (vln solo) & orchestre à cordes/with large string orchestra. Jo Boyer (arr, dir). Paris, 7/12/1956.

19. MANHATTAN (Barclay 82138) 2’20

20. TU JOUES AVEC LE FEU (Barclay 82138) 2’55

EDDIE BARCLAY & son ORCHESTRE : Roger Guérin, Fred Gérard, Maurice Thomas, Henri Vanecke (tp) ; Charles Huss, André Paquinet, Benny Vasseur (tb) ; Gabriel Vilain (bass tb) ; Mickey Nicolas, Jo Hrasko (as) ; Lucky Thompson, Marcel Hrasko (ts) ; William Boucaya (bars) ; Raymond Guiot (fl) ; cordes/strings ; Stéphane Grappelli (vln solo) ; Art Simmons (p) ; Pierre Cavalli (g) ; Jean Bouchety (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) ; Michel Hausser (vib) ; Quincy Jones (arr ; dir). Paris, 24/06/1957.

21. MINOR SWING (Véga 30 805) 3’40

22. SWING 42 (Véga 30 805) 3’01

23. PLACE DE BROUCKÈRE (Véga 30 805) 3’32

“NOTRE AMI DJANGO” : Hubert Rostaing (cl) ; André Ekyan (as) ; Stéphane Grappelli (vln) ; René Urtréger, Maurice Vander (p) ; Henri Crolla (g) ; Emmanuel Soudieux (b) ; Allan Levitt (dm) ; Géo Daly (vib). Paris, ca. août/August 1958.

Un facétieux critique remarquait jadis : “Charlie Parker sans Dizzy Gillespie ou Dizzy Gillespie sans Charlie Parker, c’est Roux sans Combalusier, Otis sans Piffre ou Jacob sans Delafond…”. Certes. Mais quand on fait les comptes, on s’aperçoit que Parker a enregistré bien plus de disques sans Dizzy qu’avec. Et pour Dizzy, la quantité se trouve encore démultipliée – question de longévité, évidemment. Même punition, même motif avec Louis Armstrong et Earl Hines, Chet Baker et Gerry Mulligan ou encore Django Reinhardt et Stéphane Grappelli (la véritable orthographe de son nom, soit dit en passant, le “y” ne remplaçant des décennies durant le “i” final que pour des questions de prononciation anglo-saxonne, afin d’éviter le fort vilain “Gappellaille”)… Les beaux duos ne sont pas forcément les plus longs. Comme l’amour en somme. Django et Stéphane, partenaires parfaits pendant cinq ans (1934-1939), duettistes superbes, d’un équilibre miraculeux, d’une puissance d’invention musicale stupéfiante, diabolique, s’estimaient fort dans la vie quotidienne… et s’agaçaient mutuellement au moins tout autant. Django, le Manouche génial et fantasque, Stéphane le violoniste le plus sage, le plus équilibré, le plus classique du jazz, étaient de toute évidence faits pour se compléter et se nourrir l’un de l’autre – heureux anthropophages ! – mais n’étaient pas nécessairement faits pour s’entendre. Plus d’une fois le pauvre spécialiste de l’instrument du Diable se fit des cheveux blancs (qui lui allaient au reste fort bien) en attendant le partenaire idéal mais désespérément absent !... Encore, pour les séances de disques on pouvait remettre au lendemain, mais pour les concerts, avec un public piaffant d’impatience… Django de son côté, grand joueur de billard devant l’Eternel, la force tranquille de sa moitié devait parfois lui donner l’envie de mordre. Des disques, ils en firent quand même beaucoup ensemble aussi inoubliables les uns que les autres (enfin, presque) et, dans la seconde moitié des années 1940, il y eut en plus nombre d’enregistrements réalisés pour la radio (voir, en particulier, les volumes 15 à 18 de l’intégrale consacrée au guitariste : Frémeaux & C° FA 315 à 318). Impossible, forcément, impensable d’y échapper. On trouvera donc ici quelques belles faces du légendaire Quintette à cordes, disposées à intervalles irréguliers, comme autant de balises. Ce ne sont pas les plus connues : un Chinatown, my Chinatown oublié de 1935 ; un Embraceable You de 1946 alors éclipsé par deux grands Nuages et une étonnante Marseillaise, et un Ol’ Man River radiophonique, aussi superbe qu’échevelé de la fin de 47… On trouvera aussi, petit comité par excellence, un duo violon/guitare, I’ve Found a New Baby (1937), ainsi que deux titres issus de la même séance, Daphné et You Took Advantage of Me, confrontant Stéphane, toujours soutenu par le plus solide des guitaristes, à deux autres monstres du violon jazz : le moelleux Eddie South, le plus tzigane sans doute des musiciens noirs américains, et son rival et ami Michel Warlop, sur le fil du rasoir, comme toujours…

Mais des disques, Django (le guitariste de Grappelli) et Stéphane (le violoniste de Reinhardt) en firent aussi tout plein séparément. Par exemple, le premier nommé enregistra à ses débuts, fin des années 1920, avec les accordéonistes musette des choses fort éloignées du jazz. Ensuite, il y eut des gravures en grand orchestre et des accompagnements de chanteurs et chanteuses pas toujours très “hot” là non plus. Plus tard encore et en bien plus long, il y eut la “drôle” de guerre et l’Occupation (quand Stéphane faisait à Londres des tas de disques sans Django !) et le nouveau Quintette du Hot Club de France où la clarinette d’Hubert Rostaing vint remplacer les cordes grappelliennes. A la Libération, les retrouvailles des deux vieux complices (concrétisées par les sessions londoniennes Marseillaise, Embraceable You, Nuages, entre autres) furent plutôt brèves, sporadiques, voire accidentelles… Ils se retrouveront bien quand même fin 1947, en 48 et encore au début de 49, à l’occasion d’un engagement à Rome donnant heureusement lieu à de fort copieuses séances pour la radio italienne. Ce fut l’ultime fois, en compagnie d’un quintette qui n’était plus tout à fait “à cordes”… Grappelli affirme qu’au printemps de 1953 on lui demanda de reformer le groupe en vue d’une nouvelle tournée, mais qu’il n’arriva pas à dénicher Django – lequel, il est vrai, savait parfois admirablement disparaître. C’est d’ailleurs à ce moment-là, le 16 mai, qu’il prit congé pour toujours… Stéphane Grappelli, de son côté, n’avait pas attendu de fonder le fameux Quintette avec Django Reinhardt pour participer à l’enregistrement de disques, parfois en qualité de violoniste et, souvent au début, en tant que pianiste. On pense qu’il a gravé pour Edison Bell quelques faces début mai 1929, au sein d’un orchestre de tango plus ou moins bidon dirigé par le nommé Orlando. C’est même à cette occasion qu’il aurait croisé le “sublime Grégor” venu lui aussi, dans le cadre du “Moulin de la Galette” à Montmartre, tourner quelques cires en compagnie de ses Grégorians. L’avisé Arménien, évidemment, l’aurait illico embarqué pour la saison d’été sur les plages. Avec lui il fera, en 1930, ses vrais premiers disques de jazz et récidivera en 1933. Parallèlement aux faces du Quintette, il y aura entre 1934 et 39 un nombre non négligeable d’accompagnements de chanteurs auquel Django ne participa pas : André Pasdoc, Éliane de Creus, Léo Marjane, Pills et Tabet, Jean-Fred Mêlé notamment. Stéphane affirmait avoir encore plus souvent rempli ce rôle d’accompagnateur à la radio, principalement comme pianiste, au cours des années 1930. Il se rappelait par exemple avoir accompagné Fréhel en plusieurs occasions. Il ne reste malheureusement plus rien de tout cela, interprété la plupart du temps en direct. En revanche, quelques disques destinés aux magasins spécialisés ont survécu. Nous n’en avons retenu qu’un, Je veux ce Soir, par Jean-Fred Mêlé, fils d’un chef d’orchestre connu qui accompagna souvent Mistinguett au “Moulin Rouge”, éphémère vedette censée donner des versions “swing” de chansons résolument modernes. On trouvera du reste dans le volume 2 (FA 082) de l’intégrale consacrée à Charles Trenet plusieurs fraîches compositions du Fou chantant alors en pleine irrésistible ascension (Rendez-Vous sous la Pluie, J’ai ta Main, Je chante, En quittant ma Ville, Fleur bleue), interprétées par un Mêlé toujours bénéficiant du superbe accompagnement Grappellien. Ensuite, il y eut le long exil londonien, aux jours (ou, plutôt, aux nuits) du “Blitz” puis après la guerre, jusqu’au milieu des années 1950. Cette période se trouve assez bien illustrée dans le CD 1 de la présente sélection… Et de 1954 jusqu’à l’orée des années 1990, Stéphane, n’a plus guère cessé d’enregistrer, en France ou bien ailleurs, avec des dizaines de partenaires – dont la plupart des autres Grands du violon, comme Stuff Smith, Joe Venuti, Ray Nance, Svend Asmussen, Jean-Luc Ponty et aussi… Yehudi Menuhin). Tous, sauf bien sûr le génial Manouche des jours radieux… Est-il donc besoin de dire que, lui aussi, a fait bien plus de disques sans Django qu’avec…

C’est deux ans et trois jours avant le sieur Reinhardt (26 janvier 1910, en Belgique) que Stéphane vit le jour à l’hôpital Lariboisière, dans le dixième arrondissement de Paris. Soit le 23 janvier 1908, veille de l’anniversaire de Mozart… Il vint au monde italien, ce petit, parce que son papa Grappelli, Ernesto, débarquait de la Péninsule, fuie à dix-neuf ans pour d’obscures raisons, probablement politiques. Sa maman, native de Calais, ne fit qu’un bref passage sur cette terre. Quand le gosse eut trois ans, elle tira sa révérence, laissant sa progéniture à un père attentionné mais désemparé, rêveur fou de musique, de solfège, d’auteurs latins et grecs, guère préparé à s’occuper d’un petit enfant. Il le confia donc à un orphelinat austère puis, bien mieux, à l’école de danse qu’avait fondée en France la célèbre Isadora Duncan. La guerre, hélas, mit fin à ce doux répit et les institutions pour pauvres, plus sinistres les unes que les autres, furent de nouveau le lot quotidien du gamin, pour qui la période 1914-1918 fut à peu près aussi dure que pour un Poilu. L’enfance de Stéphane Grappelli fait parfois penser à Dickens… On ne l’envoya tout de même pas voler – sauf de ses propres ailes ! Revenu entier de la boucherie, remarié avec une chipie et bientôt père d’un nouveau lardon, Ernesto fit naturaliser son premier fils et l’emmena le dimanche aux concerts Colonne écouter les grandes symphonies et les Français presque contemporains, Debussy et Ravel. Il lui offrit aussi son premier violon et lui recopia des passages d’œuvres musicales célèbres. Stéphane Grappelli fut inscrit au Conservatoire de Paris le dernier jour de l’an 1920 pour une durée de trois ans. En même temps, il se mit à faire la manche au violon dans les cours, puis se vit engager dans des orchestres de fosses chargés d’accompagner les films muets dans les salles Gaumont. Arrivé en France avec le corps expéditionnaire américain lors de l’entrée en guerre des Etats-Unis, le jazz se signala au jeune musicien par le truchement du phonographe : grâce à un appareil à sous, ancêtre français du juke-box, il découvrit par hasard le Stumbling des Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, l’une des cinquante-deux faces par cette formation afro-américaine que la maison Pathé édita sur ses disques “à saphir”en 1922-23. D’autres thèmes suivirent, rapidement adoptés par l’orchestre de fosse pour accompagner les films américains “modernes”. Grappelli joua aussi dans les écoles de danse, fort prisées en ce temps-là. Il y croisa le pianiste Stéphane Mougin qui l’aida beaucoup. Par lui, il connut des garçons de son âge comme le trompettiste Philippe Brun, le tromboniste/polyinstrumentiste Léo Vauchant-Arnaud, le saxophoniste André Ekyan : rien que des passionnés de la nouvelle musique qui, à l’un ou l’autre moment, seront récupérés par Grégor – lequel ne pratiquait aucun instrument, mais savait étonnement vendre musique et musiciens !... Une équipe dont Django Reinhardt, qui évoluait dans d’autres circuits, ne fera jamais partie… C’est en qualité de pianiste que Stéphane fut engagé vers le milieu de 1929 ; il déclarait volontiers que ce fut toujours là son instrument de prédilection et qu’au début, Grégor ne savait même pas qu’il jouait aussi du violon – peu vraisemblable, disons-le. Toujours est-il que dans un court “film attraction” du début de 1930, montrant le groupe dans un de ses sketchs, quand Pierre Allier remplaça Philippe Brun et que Michel Warlop n’était pas encore membre de la bande, c’est bien au violon que l’on repère Grappelli, encadré par deux collègues difficilement identifiables… L’équipe (moins Warlop, arrivé au printemps 30) fit une tournée en Amérique du Sud à l’automne. C’est justement dans ce coin du monde, en Argentine, que Grégor s’exila l’année suivante, pour des histoires de responsabilités dans un grave accident d’automobile (et aussi, probablement, pour des questions d’impôts impayés !). Là-bas, il trouva moyen de graver en septembre 1931 quatre faces comme chef d’un orchestre, composé de musiciens locaux, chargé d’accompagner Carlos Gardel chantant en français ! Contrairement à l’affirmation de certains discographes, aucun des Grégoriens d’origine ne participa à la dite séance. Ceux-ci s’étaient dispersés dans diverses formations. Grappelli, par exemple, joua un temps (comme violoniste) chez Ray Ventura et chez Lud Gluskin (1931-32). A noter que, dans ces temps anciens, il lui arrivait aussi de pratiquer le saxophone !...

Amnistié, Grégor retrouva l’Europe fin 32 et monta aussitôt un nouveau grand orchestre, avec entre autres Pierre et Roger Allier, Ekyan, Roger Fisbach, Alix Combelle, Warlop au violon, Michel Emer et Grappelli cette fois bel et bien pianiste. C’est du moins ainsi qu’on l’aperçoit, assis face à son clavier lors d’une scène de music-hall, dans la version 1933 de Miquette et sa Mère, adaptée pour le cinéma de la pièce de De Flers et Caillavet par Henri Diamant-Berger, avec Blanche Montel, Claude Dauphin et l’incroyable Michel Simon. La bande-son de la séquence est écoutable dans le recueil Ciné Stars (Frémeaux FA 063). Grégor décrocha une exclusivité phonographique avec la firme Ultraphone. Pour ce qui touche Stéphane violoniste, seul Fit As a Fiddle, sur les trente-six faces gravées dans l’année, présente un réel intérêt : les premiers pas sur disque de Grappelli à l’archet… Malgré un succès certain, l’orchestre ne trouva que peu d’engagements en cette époque de Crise aigue et fut dissout après la saison d’été. Exit Grégor… Michel Warlop tenta à son tour l’aventure du grand orchestre, avec les ex-Grégoriens (dont Stéphane au piano), mais lui non plus ne tint pas la route. Parfois, un flamboyant guitariste se glissait dans la place. Il avait intégré le monde du jazz après les autres, mais avait en un clin d’œil rattrapé son retard et commençait déjà à les dépasser tous. On raconte que ce garçon à l’œil parfois noir avait un soir abordé Grappelli à la “Croix du Sud”, une boîte de Montparnasse où celui-ci se produisait en compagnie d’Ekyan et du pianiste Alain Romans. Il lui avait proposé une association musicale : la fondation d’un petit orchestre à cordes essentiellement appelé à jouer du jazz. Django (car c’était lui) fit une démonstration et Stéphane se déclara ébloui… mais ne donna pas suite. Alors Django, suivant sa bonne habitude, partit en voyage, sûrement en verdine. Quand donc aurait eu lieu ce premier contact ? Grappelli avance fin 1930, date trop ancienne, hautement improbable pour des tas de raisons… Stéphane Grappelli avait décidément une merveilleuse mémoire à éclipses… Fin 31 ? Difficile : Django, cap au Sud, écoutait ses premiers disques de jazz (Armstrong, Ellington, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang…), jouant occasionnellement à Toulon et Cannes avec Louis Vola. On l’entrevoit dans un film du printemps 1932, Clair de Lune, autre réalisation de Diamant-Berger avec, là encore, Blanche Montel et Claude Dauphin… Alors, plutôt fin 32 ? Bonne idée – ce qui expliquerait le refus momentané de Grappelli : Grégor était de retour et montait un nouveau gang dont il devait faire partie. Durant l’hiver 1932-33 en tous cas, Django était bien à Paris et jouait dans l’orchestre de “la Boîte à Matelots”. Toujours est-il qu’au fil de l’an 1934, il fut fréquemment intégré à l’orchestre Warlop et participa à la plupart des séances de disques, accompagnement de chanteuses inclus. Grappelli et lui se retrouvèrent également en studio avec les musiciens – en fait à peu près les mêmes que chez Warlop – que dirigeait le tromboniste Guy Paquinet (alias Patrick). Surtout, il y eut à l’été de cette année-là les fort sélects thés dansants de l’Hôtel Claridge, auxquels participèrent activement les deux déjà vieux complices, le guitariste Roger Chaput, le bassiste Louis Vola. Pendant les pauses, ils s’amusèrent souvent à improviser sur des standards américains qui leur plaisaient. Ainsi donc, le petit orchestre à cordes que voulait monter Django avec Stéphane venait de voir le jour, à l’improviste presque… Il suffisait d’ajouter un second guitariste d’accompagnement, Joseph Reinhardt, le petit frère, et de se lancer à la conquête de la gloire ! Pour cela, ces cinq garçons dans le vent purent rapidement compter sur le Hot Club de France récemment fondé, dont leur formation deviendra tout naturellement l’emblème. Deux de ses membres, Charles Delaunay et surtout Pierre Nourry, gagnés à la cause, se transformèrent en diligents impresarii. On leur fit faire quelques cires d’essais en septembre, mais la prudente maison Odéon jugea tout cela “trop moderne”, tandis que la firme Ultraphone se montra intéressée, non sans avoir au passage marchandé sur les cachets ! Dans ses Mémoires (Mon Violon pour tout Bagage – Calmann-Lévy, 1992) Grappelli remarque : “Nous avons touché cent francs chacun, un franc actuel, pour l’enregistrement. C’était le 2 décembre 1934”. Il ne s’est sûrement pas rendu compte, Stéphane, que cent francs de 1934 n’ont pas tout à fait la même valeur qu’un franc des années 1990 et qu’avec cent balles, fin 34, on pouvait casser la croûte pendant une quinzaine, à condition de n’être pas trop gourmand ! Quant à cette date du 2 décembre, elle tombe pile un dimanche, jour où l’on n’enregistre guère (surtout des gens pas spécialement célèbres), mais coïncide en revanche avec le premier concert public du Quintette, donné en l’École Normale de Musique. La première séance Ultraphone eut lieu en réalité le 11 ou le 12, ainsi que l’a déterminé cette fouineuse d’Anne Legrand… Les engagements au cours de la période 1935-39, même quand ils se déroulèrent à l’étranger (Scandinavie, Italie, Belgique, Suisse, Hollande, Grande Bretagne…), ne furent jamais de très longue durée et contraignirent assez souvent les musiciens à trouver de l’embauche séparément dans d’autres formations. Au fond, le fabuleux Quintette du Hot Club de France, célèbre un peu partout dans le monde, ne fut jamais complètement régulier…

Á partir de 1935, le Quintette enregistra abondamment pour des firmes plus importantes qu’Ultraphone : Decca, His Master’s Voice/Gramophone, puis Swing, la nouvelle marque (distribution Pathé Marconi) fondée en 1937 par Delaunay avec le concours d’Hugues Panassié, destinée à capter le jazz sous toutes ses formes. Ces disques furent pour la plupart largement édités à l’étranger, ce qui, ajouté aux émissions radiophoniques internationales (y compris en direction du continent américain), contribua grandement à établir la réputation exceptionnelle du groupe. En vue de la tournée dans les îles britanniques de l’été 38, un court-métrage promotionnel vit le jour – du moins, un seul a été retrouvé, mais il y en eut peut-être plusieurs. L’entreprise fut couronnée de succès et le très professionnel impresario anglais Lew Grade expédia la bande en Suède et en Norvège, avant de récidiver l’année suivante dans une atmosphère plutôt tendue. L’annonce de la déclaration de guerre à l’Allemagne par l’Angleterre et la France le 2 septembre 1939 provoqua la panique chez les guitaristes et le bassiste, qui se rembarquèrent précipitamment pour le continent, laissant Stéphane seul à Londres, désemparé, en assez mauvaise santé. Ce délicat valétudinaire devint à un poil près nonagénaire ! Il affirme qu’une fois rétabli, il ne lui fut plus possible de traverser le Channel. Se doutait-il qu’en restant ainsi dans l’île, il courait en somme bien plus de risques qu’en regagnant Paris, de périr sous une bombe ennemie – sort que plusieurs de ses ami(e)s ne purent éviter ? Certainement pas, sinon il n’eût point manqué de trouver un moyen de passer la Manche… Ce fut là, évidemment, le commencement de la fin du Quintette à cordes du Hot Club de France. De retour à Montmartre, Django joua à droite et à gauche, en compagnie de partenaires occasionnels, non mobilisés ou en permission. Puis avec l’Occupation, la clarinette prit la place du violon… Stéphane, de son côté, n’eut guère de mal à trouver du boulot dans un pays où il était déjà bien connu. Dès décembre 39, il intégra en qualité de soliste exceptionnel le “Swingtette” que devait diriger le pianiste Arthur Young dans le cadre du très huppé restaurant de Piccadilly connu sous le nom de “Hatchett’s”. Á partir de 1941, il dirigea ses propres formations à géométrie variable. C’est donc en compagnie de ses deux séries de groupes qu’il fit un assez grand nombre de disques chez Decca entre la fin de 1939 et 1945. On note que, tout comme lui, d’autres musiciens passèrent souvent de l’une à l’autre formation, à commencer par la chanteuse Beryl Davis, suivie par les guitaristes Noël “Chappie” d’Amato et Jack Llewelyn, le remarquable pianiste George Shearing (appelé à faire par la suite une jolie carrière outre-Atlantique), ou encore le violoniste/saxophoniste Dennis Moonan, qui reprit la direction du Hatchett’s Swingtette quand Young fut blessé dans un bombardement. On a souvent reproché à ce Swingtette d’être davantage, malgré la présence de son illustre invité, un groupe de musique de genre que de jazz proprement dit. Et il est vrai que le son du “novachord”, sorte de piano électrique assez vaseux alors pratiqué par Young, donnait à l’ensemble une sonorité vaguement “novelty”, parodique, aux antipodes du féroce expressionisme du défunt Quintette. Les faces gravées directement sous la houlette du violoniste présentent néanmoins un intérêt plus grand, même si, là encore, le ton s’est radouci par rapport à celui de la glorieuse avant-guerre. Sans Django et l’accompagnement parfois un peu raide du Quintette, Stéphane trouve davantage matière à s’émanciper, à alléger son jeu, à découvrir sa propre “modernité”. Nul doute que la présence quasi constante à ses côtés de Shearing ne lui ait été, dans ce domaine, d’un grand secours. De toute évidence, son attirance avouée pour l’harmonie a permis à Grappelli de trouver d’emblée dans ce jeune pianiste aveugle un partenaire presque aussi accompli que le Manouche. Quant aux guitaristes justement, leur rôle fut la plupart du temps pour le moins effacé, comme si Stéphane reprenait son souffle…

Le Manouche refit surface, on l’a vu, au début de 1946. Lui aussi avait changé. Il s’était produit chez l’un et l’autre une sorte de glissement, créant une distance qui irait s’accentuant au fil des jours et empêcherait tout retour durable à l’esthétique du passé. Les retrouvailles n’en furent pas moins émouvantes et les enregistrements de première classe. Mais on ne put aller beaucoup plus loin, du fait des engagements respectifs des deux vieux complices. Peu après, Django fit ses valises – oubliant sa superbe guitare à pan coupé – et s’en fut en Amérique jouer dans l’orchestre de Duke Ellington – ou, plus exactement, à côté. Expérience décevante, dont il sortit désenchanté dans le courant de 1947. Grappelli, de retour en France pour la première fois à l’automne de cette année-là, enregistra quatre faces pour Swing, non pas avec le Manouche aîné, mais avec Joseph le cadet, signataire d’un des morceaux. Stéphane attendra 1954 pour faire de nouveaux disques (45 et 33 tours) sous son nom. Entre-temps, il enregistra tout de même d’autres faces Swing du Quintette (1948) et il y eut, avec Django, les radios françaises de 1947 et les italiennes de 49 déjà signalées. Durant cette période, 46-54, il se partagea entre l’Angleterre toujours très accro, la France légèrement dédaigneuse et l’Italie, où il rechercha les racines de sa famille. L’Amérique, l’Australie, seront pour plus tard, mais ça viendra ! Il ne rentra finalement au pays qu’en 1954. Sa première séance, organisée par le pianiste Jacques “Jack” Diéval (son partenaire durant l’été à “L’Escale”, de Saint-Tropez), prit place dans la série Jazz aux Champs-Élysées. Il enchaîna sur une association très libre avec le guitariste virtuose Henri Crolla, grand admirateur de Django (dont il reprit les compositions, mais qu’il se garda d’imiter) et accompagnateur régulier d’Yves Montand (voir les trois volumes de l’intégrale dévolue au chanteur). En sa compagnie il se produisit assez souvent à l’époque au “Club Saint- Germain”, que Django avait beaucoup fréquenté vers la fin. Malheureusement, Crolla (1920-1960) ne fit point de vieux os lui non plus, qui raccrocha sa guitare sept ans seulement après Django. Par chance, plusieurs disques réalisés en ces années-là, le livrent à son zénith. Grappelli enregistrait alors surtout pour Eddie Barclay. Mais il lui arrivait déjà de se retrouver chez Decca ou Véga. La rançon du succès… Ensuite, il fit des disques un peu partout, presque chez tous les producteurs de la place de Paris, de Londres, de New York, de Montreux, de Copenhague… Á tel point que l’on parlera de “banalisation”. Pour mémoire, signalons que les duos avec Menuhin (entre 1972 et 1985) furent produits par EMI, alors que les titres avec Kenny Clarke virent le jour chez RCA, MPS et Festival. Et il n’y eut pas que les duels entre chers violonistes. On en trouvera aussi, sur vinyle, avec les délicieux pianistes Earl Hines, Oscar Peterson, Martial Solal, Hank Jones, Johnny Guarnieri, George Shearing, Raymond Fol… Sans compter les clins d’œil aux subtils guitaristes connus ou oubliés : Barney Kessel, Philip Catherine, Jimmy Shirley, Pierre Cavalli, Jimmy Gourley, Baden Powell, Larry Coryell, Joe Pass, Bucky Pizzarelli, Martin Taylor et, des années durant, Diz Disley…Un vrai festival à lui tout seul, Stéphane Grappelli ! Après avoir longtemps travaillé en compagnie du pianiste Marc Hemmeler, dans les dernier temps, il accorda sa préférence au trop modeste Marc Fosset : choix judicieux… Ces innombrables enregistrements d’après 1960 sont évidemment hors de notre portée mais, au fond, est-ce si regrettable ? La sélection ici présentée ne constitue-t-elle pas réellement la “quintessence” ?

Stéphane Grappelli joua sans doute au cours des années 1960-70-80 dans tous ces pays que les anti-communistes désignaient sous le nom de “monde libre”. Il avait une vision émue de la chère Australie et un souvenir terrifié du diabolique Newport 1969, où il triompha pourtant, alors que les tenants du “jazz traditionnel” (be-bop compris) se firent quasiment tous lyncher… Sinon, en dehors des (nombreux) festivals, il se produisait gentiment à longueur d’année sur la Tour Eiffel, ce “Toit de Paris”, où le jazz ne pouvait être que doux… Ainsi s’écoulaient les jours tranquilles à Montmartre. Puis l’âge venant, le violoniste, toujours fringant, finit quand même par prendre ses distances. Mais en 96, il jouait encore ici ou là, à l’occasion … Le 1er décembre 1997, une sèche dépêche de l’AFP vint le rappeler à l’ordre en lui signifiant qu’il ne jouerait plus jamais de violon ou de piano, vu qu’il venait de mourir. Le vieux monsieur au grand sourire et aux jolies chemises à fleurs s’est éteint à l’endroit même où il avait vu le jour nonante hivers plus tôt (à moins de deux mois près) : l’hôpital Lariboisière, toujours sis dans le dixième arrondissement de Paris. Il a eu beau se balader dans le monde entier, connaître la gloire à Newport, Melbourne, Rome ou Nice, passer des années en Angleterre, être réclamé par Norman Granz et Ellington, le dixième, à trois pas de Montmartre, était son pays. Il l’a souvent quitté, il est toujours revenu, lui, le rejeton d’un émigré rital pas très bien vu de l’autre côté des Alpes… En passant par le grand cercle des honneurs, Stéphane Grappelli a fini par boucler sa petite boucle à lui : du dixième au dixième. Et réciproquement… Peut-être, lui qui remerciait chaque jour le Bon Dieu d’avoir “inventé” le jazz, ne se tenait-il plus d’aller rejoindre au paradis du swing tout un tas de vieux copains qui se livrent là-haut, depuis belle lurette, aux joies de la jam-session éternelle. Django, Joseph, Vola, Warlop, Chaput, Ekyan, Combelle, Brun, Renard, bien sûr, qui furent si souvent ses compagnons de route, mais aussi ceux qu’il ne cessa d’admirer : Tatum, Fats Waller, Satchmo, Bix, Coleman Hawkins, Duke, Joe Venuti, Eddie South, Stuff Smith… Tant qu’il en restait un, on pensait – naïvement, c’est sûr – que le légendaire Quintette à Cordes du Hot Club de France, le seul, le vrai, celui de 34-39, vivait encore quelque part, ailleurs, dans un trou du temps et de l’espace, et que son cœur battait toujours. Quand celui de Stéphane Grappelli s’est arrêté, on a su que cette déchirure spacio-temporelle chère à la science-fiction avait fait long feu. Les essais de reconstitution de l’après guerre tendaient déjà à prouver que le vieux Quintette avait vécu. Le 1erdécembre 1997, il est définitivement entré dans l’Éternité.

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLI

Á propos de la présente sélection

Les six faces dans lesquelles intervient Django Reinhardt se trouvent évidemment dans l’intégrale consacrée au guitariste. En revanche, elles ne figurent pas dans les deux recueils de la série “Quintessence” dévolus au fier Manouche. La version radiophonique ici présentée d’Ol’ Man River est différente de celle, gravée pour le disque, incluse dans le Quintessence FA 226. Plus longue, elle est surtout beaucoup plus enlevée et enthousiaste : une des plus belles réussites de ces retrouvailles incertaines. Une sorte de chant du cygne… Pour son premier solo de violon enregistré sur Fit As a Fiddle, en 1933, Grappelli ne disposait pas de son instrument au studio, puisqu’il était alors pianiste. Il emprunta donc celui de Michel Warlop. D’ailleurs s’il est à peu près sûr que le premier solo est bien de lui, il est assez probable que le second, plus court, vers la fin, est dû au véritable propriétaire du plumier. Plus tard, Warlop fit cadeau à Stéphane de son violon (celui-là ou un autre), lui demandant de le remettre ensuite à ceux qu’il jugerait dignes de le posséder. Ainsi fut fait et Jean-Luc Ponty puis Didier Lockwood devinrent titulaires de l’instrument. Le pianiste Pierre (Piero) Zeppilli, originaire lui aussi d’Italie, travaillait surtout avec Michel Warlop, justement. Pour cette raison, quelques collectionneurs ont cru qu’il était le violoniste dans les séances Polydor de Jean-Fred Mêlé. Pourtant, le long solo de violon sur Je veux ce Soir ne laisse subsister aucun doute quant à l’identité de son auteur : aussi éloigné que possible du jeu nerveux, inquiet et tranchant de Warlop, il est parfaitement typique du style rond, chaleureux, plein d’aisance, de Grappelli à l’époque. On a souvent critiqué la place prise par la chanteuse Beryl Davis dans les faces du Hatchett’s Swingtette, puis dans celles publiées sous le nom du violoniste en exil. Beryl Davis, toute jeune, avait chanté et enregistré en compagnie du Quintette, lors des tournées de celui-ci en Angleterre et en Scandinavie. Elle fut qualifié de médiocre, alors qu’elle possède une voix plutôt agréable (How Am I to Know ?), même si on peut lui préférer celle de Doreen Henry (Out of Nowhere). Les séances de juillet 1940 et de février 41, dont sont issus I Never Knew, Tiger Rag et Stéphane’s Blues, font irrésistiblement songer, avec leur ribambelle de violons, au fameux Septuor à Cordes que dirigea en France occupée, de 1941 à 1944, Michel Warlop. Pourtant, Michel n’avait pu entendre les disques de Stéphane, ni Stéphane ceux de Michel. Peut-être leur était-il arrivé, avant guerre, de rêver de conserve d’un groupe de jazz entièrement constitué de cordes, avec forte prédominance de violons ? Un rêve qu’ils finirent par réaliser l’un et l’autre, chacun à sa façon. Les faces éditées sous le nom bizarre de Witley Court Music Box étaient destinées à la RAF et ne furent jamais commercialisées. Les “V-Discs” anglais en quelque sorte (et en plus modeste). Grappelli participa à une séance de mars 1941. Apparement, ces raretés n’avaient guère été rééditées. Pour la première séance du retour, le 17 octobre 1947, sans Django mais avec Joseph Reinhardt, on avait prévu deux titres en quartette, Oui, pour Vous revoir et Soleil d’Automne, et deux solos de piano, Bebop Medley et un Tea for Two très inspiré de Tatum. Mais, accidentés à la galvano, Soleil d’Automne et Bebop Medley n’ont pu être pressés. Dommage, surtout pour le solo : on était curieux de voir comment Stéphane pouvait traiter le nouveau style, lui qui, contrairement à Django, disait s’en être désintéressé assez vite parce qu’il le trouvait trop mécanique ! Cela ne l’empêchera pas de jouer plus tard avec Kenny Clarke et quelques Jeunes Turcs du jazz français, notamment les pianistes Raymond Fol ou Maurice Vander – lequel pratique d’ailleurs le clavecin sur Someone to Watch over Me… Il lui arriva aussi de donner ses propres versions de thèmes imaginés par les boppers ou assimilés, tel Pent Up House de Sonny Rollins. Si les compositions de Django ont la part belle dans le présent recueil, on remarquera que les standards des grands compositeurs populaires américains, Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin n’ont rien à leur envier. Stéphane Grappelli disait en raffoler et se plaisait toujours à en caser plusieurs dans ses disques et récitals. Blue Skies, I Got Rhythm, le très prenant The Folks Who Live on the Hill, Embraceable You, Ol’ Man River, Can’t Help Lovin’ That Man, A Girl in Calico, S’Wonderful, Someone To Watch over Me, Looking at You… sont là pour en témoigner.

Daniel NEVERS

Remerciements à Tony Baldwin, Alain Délat, Yvonne Derudder et Anne Legrand.

© 2010 Frémeaux & Associés – Groupe Frémeaux Colombini SAS

english notes

STEPHANE GRAPPELLI

A facetious critic once observed, “Charlie Parker without Dizzy Gillespie, or Gillespie without Parker, is like Smith without Wesson, Sears without Roebuck, or Mercedes without the Benz...” Quite. But if you’re referring to the Parker-Gillespie discography, and you count the Parker records, you can see that he made a lot more of them without Dizzy than he did with him. And as for Dizzy, you can multiply that number and then add a few – after all, he did live longer. The same goes for Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines, Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan or, indeed, Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli – which is the correct spelling: a “y” replaced the “i” for decades, just to avoid the ugly “Grappell-eye” pronunciation of Stéphane’s name, by English-speakers in particular. The best pairings do not necessarily last the longest, as many lovers can testify. Django and Stéphane were perfect partners for five years, from 1934 to 1939. In music they were superb duettists, with miraculous balance and astounding, even fiendish inventiveness, and they had a healthy respect for each other outside their music as well. They also got on each other’s nerves in the same proportions. Django was the guitar’s whimsical “gypsy genius”; Stéphane was the most well-behaved, most stable, most classical violinist in jazz; and the two were complementary, with each feeding off the other – happy cannibals! – although that didn’t necessarily mean they were always in harmony: time and again, the poor practitioner of the Devil’s instrument discovered another white hair while he was waiting for his soul-mate to turn up... Which wasn’t exactly the end of the world if their record-session could be postponed for another day, but when they were due to go on stage together, with audiences fidgeting impatiently in their seats, it was another matter entirely: Django adored playing billiards, but one can imagine how often his partner was tempted to break his cue in half... All the same, they did make a considerable number of records together, and every one (or almost) was as unforgettable as the next; in addition, the second half of the Forties saw many radio-recordings as well (cf. volumes 15-18 of the guitarist’s complete recordings, released by Frémeaux & Co. under the references FA 315-318). Those are impossible to forget. So here we have some of the finest sides ever to come from their legendary string Quintette, recordings spread over irregular intervals like so many buoys marking a channel for navigators. These are not always their most famous pieces: there’s a Chinatown, my Chinatown that has been overlooked since 1935; an Embraceable You made in 1946 that was eclipsed by two great versions of Nuages and an astonishing Marseillaise anthem, and also a late-1947 radio broadcast of Ol’ Man River that’s as superb as it is wild... There’s also a 1937 recording by this small group par excellence – the violin/guitar duet – entitled I’ve Found a New Baby, together with two titles taken from the same session, Daphné and You Took Advantage of Me, where Stéphane, still sustained by the most solid guitarist in the world, faces up to two other monsters of the jazz violin: the suave Eddie South, no doubt the black American musician with the most gypsy in his soul, and his rival and friend Michel Warlop, playing, as usual, extremely close to the edge… But Django, “Grappelli’s guitarist”, and Stéphane, “Reinhardt’s violinist”, made dozens of records separately. The former, for example, when he was just starting out at the end of the Twenties, made many records with musette accordionists whose music was a long way removed from jazz. And there were also his big-band recordings, plus some titles on which he accompanied singers (both male and female) that weren’t always that “hot” either. Later, and for a much longer period, came the years when there was a war on, and a dark Occupation was provoked in France (during which Stéphane made a pile of records in London without Django!), years that saw the birth of a new Quintette du Hot Club de France, or QHCF, in which Hubert Rostaing’s clarinet replaced Grappelli’s strings. When the Liberation came, reunions between the two old partners – sealed by the London sessions that produced the Marseillaise, Embraceable You and Nuages, among others – were rather short and sporadic, not to say accidental... yet they did get back together late in 1947, again in 1948, and also early in 1949 when, fortunately, a concert in Rome gave Italian radio the opportunity to record a wealth of material. It would be the last time they played together, although it wasn’t the real string quintet... Grappelli said that he was asked to reform the group in the spring of 1953, with a view of taking the band on tour, but he couldn’t get his hands on Django... who, of course, was still quite capable of vanishing into thin air if he’d set his mind to it. And it was then, of course – on May 16th precisely – that Django bid his final farewell.

As for Stéphane Grappelli, he hadn’t waited for the foundation of the famous Quintette with Django Reinhardt to start making records; sometimes he played the violin, and sometimes the piano, especially in his early career. He’s thought to have made a few sides for Edison Bell (May 1929), playing with a (fake) tango ensemble led by a gentleman named Orlando. It’s also said that it was at this time that he met a “sublime personality” known as “Grégor” (who’d also made some discs sides in Montmartre at the “Moulin de la Galette” dancing), and that Stéphane recorded a few sides with the latter’s “Grégoriens” orchestra before that canny Armenian entrepreneur whisked Grappelli off to the coast for his summer season. Whatever, it was with Grégor, in 1930, that Stéphane made his first genuine jazz records, and in 1933 he waxed some more. Between 1934 and 1939, when he wasn’t recording his Quintette sides, Grappelli was also accompanying a whole host of singers with Django nowhere in sight: there was André Pasdoc, Éliane de Creus, Léo Marjane, Pills and Tabet, or Jean-Fred Mêlé. Stéphane said that accompanying singers on the radio was a more frequent occupation for him in the Thirties than making records, and that on those occasions he usually played the piano; he remembered being Fréhel’s pianist in particular. Of all this, unfortunately, there remains no trace, as the microphones used by radio-stations usually sent the sound over the air directly, but not to any form of recorder. Some traces of Grappelli have survived, however, in the form of records made for specialist-shops, and one of them is included here, Je veux ce Soir, by Jean-Fred Mêlé, the son of a well-known bandleader who often accompanied Mistinguett at the Moulin Rouge; Mêlé was (briefly) a star who delivered allegedly “swing” versions of some resolutely modern songs. Volume 2 of Charles Trenet’s complete recordings (Frémeaux FA 082) contains several renditions (Rendez-Vous sous la Pluie, J’ai ta Main, Je chante, En quittant ma Ville, Fleur bleue) cut by “madcap singer” Trenet, then on his irresistible rise to fame, together with a shining Mêlé who still had the advantage of Grappelli’s superb accompaniment. A lengthy London exile followed for Stéphane – the dark days (or nights, rather) of the Blitz – followed by a post-war period lasting until the middle of the Fifties. That period is well-documented by CD1 of this selection. From 1954 until the Nineties, Stéphane hardly ever stopped recording – both in France and in many other places – and he had dozens of partners, many of them among the greatest violinists you could name: Stuff Smith, Joe Venuti, Ray Nance, Svend Asmussen, Jean-Luc Ponty... even, unforgettably, Yehudi Menuhin. But of course he wasn’t paired with the gypsy Genius again: it was long after their partnership had been abbreviated... So Grappelli made many more records without Django than he did with him.

Stéphane Grappelli was born two years and three days before Django Reinhardt (the latter in Belgium, on January 26th 1910), and he first saw the light of day at Lariboisière Hospital in the 10th arrondissement of Paris: on January 23rd 1908 precisely, the eve of Mozart’s anniversary. Stéphane was born an Italian. His father, Ernesto Grappelli, had fled his native country at nineteen for reasons that are obscure but were probably political. Stéphane’s mother was from Calais, but her life was a short one; she passed away when Stéphane was only three, leaving her offspring with a father who cared for him, but who was also rather out of his depth: Ernesto was something of a dreamer, especially when it came to music, and he also loved reading the Romans and the Greeks, which hardly prepared him for raising a little boy. First, he sent him to an austere orphanage; then, a happier option, he confided Stéphane to a dance-school founded by the celebrated Isadora Duncan. The Great War, unfortunately, put an end to this idyll and the boy’s artistic surroundings were replaced by institutions for the poor, each more sinister than the next. The years 1914-1918 were tougher on young Grappelli than on some who’d been in the war: his childhood was worthy of a tale by Charles Dickens, although no Fagin tried to turn him into a thief. Ernesto escaped the war unharmed, and then remarried – his wife was supposedly a vixen – before fathering another son. In due course Stéphane was naturalised and his father took him along to the famous Colonne concerts, introducing him to the great symphonies and some French composers who were almost contemporaries: Debussy and Ravel. He also gave him his first violin, and transcribed famous pieces of music for him. Stéphane Grappelli joined the Conservatoire in Paris on the last day of 1920 and remained there for three years. During that period he began busking, playing his violin in the streets, and then he found jobs with some of the pit-orchestras who played during the silent films screened at Gaumont cinemas. When jazz arrived in France with the American Expeditionary Corps, the young violinist discovered its existence thanks to a phonograph: a coin-machine, one of the jukebox’s ancestors, was playing Stumbling by Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, one of the 52 sides by this Afro-American ensemble that Pathé released in France as a “Sapphire” record in 1922/23 (a special stylus was needed to play them). Other tunes followed Stumbling into Stéphane’s imagination, and they were quickly taken up by the pit-orchestras looking for music to play behind “modern” American movies. Grappelli also played at some of the “dance schools” that were extremely popular then; he bumped into pianist Stéphane Mougin at one of them, and Mougin took him under his wing. Mougin introduced him to other youngsters like trumpeter Philippe Brun, trombonist/multi-instrumentalist Léo Vauchant-Arnaud, or saxophonist André Ekyan: all of them fans of the new music being played, and all of them musicians who were later snapped up by the bandleader known as “Grégor” – a man who didn’t play an instrument, but who showed amazing talent in selling his orchestra’s music and those capable of playing it! His orchestra was a team to which Django never belonged, incidentally, as Reinhardt was much too involved in other spheres... Grégor hired Stéphane – as a pianist – in the middle of 1929; Stéphane went on record as saying that, at the time, he preferred the piano to the violin, and that Grégor didn’t even know that Stéphane was also a violinist... which, it should be said, is hardly likely. Whatever the truth, it was not as a pianist, but as a violinist that Stéphane Grappelli first drew attention: in a short - film made early in 1930, there’s one scene (with Pierre Allier replacing Philippe Brun, but without Michel Warlop not yet a member of the band), where you can see Grappelli playing his violin sandwiched between two of his comrades (who have remained nameless to this day...) That band – minus Warlop, who arrived in the spring of 1930 – undertook a tour of South America that autumn. It was there, in Argentina to be precise, that Grégor went into self-imposed exile the following year (officially, due to his responsibility for a serious car-accident and, unofficially and more likely, for reasons that not totally unrelated to tax-evasion). In 1931, while in South America, the bandleader somehow managed to record four sides with a bunch of locals (he’d been entrusted with providing the backing-group for Carlos Gardel, who was singing in French). Whatever the discographies say, none of the original “Grégoriens” took part in that session: they’d already gone their separate ways. Grappelli, for example, played for a while with Ray Ventura, and also Lud Gluskin (1931-32). He played violin with them, but in those days, as a matter of fact, it wasn’t that rare for him to be seen with a saxophone in his hands either...

An amnesty brought Grégor back to Europe at the end of 1932; at once he organised another big band and this time it featured Pierre and Roger Allier, Ekyan, Roger Fisbach, Alix Combelle, Warlop on violin, Michel Emer, and Grappelli, this time definitely as a pianist. At least, that’s what you can see in the 1933 film Miquette et sa Mère, adapted for the screen by filmmaker Henri Diamant-Berger from a play by De Flers and Cavaillet (it starred Blanche Montel and the incredible Michel Simon): there’s no mistake, Stéphane Grappelli is seated behind a keyboard in a music-hall scene. The scene’s soundtrack can be heard in the Ciné Stars anthology (Frémeaux FA 063). Grégor signed an exclusive contract to record for Ultraphone; as for Stéphane the violin-player, only Fit as a Fiddle, one of the thirty-six sides he made in 1933, has any real interest: it was the first time that Grappelli used a fiddle on record... Despite some success, the orchestra had a lot of trouble finding enough bookings to keep it solvent – a result of the Depression – and it disbanded after the summer season. Exit Grégor… Michel Warlop, in turn, tried his hand with a big band (composed of “Grégoriens” alumni, including Stéphane on piano), but he had no more luck with the format than his predecessor. And then a flamboyant guitarist began slipping into the picture from time to time. He’d come into the jazz world after the others, but he made up for lost time in the wink of an eye, and soon he’d overtaken them all. The story goes that one evening, this dark-eyed guitarist – who was indeed capable of a black look now and then – had button-holed Grappelli at the “Croix du Sud”, a club in Montparnasse where Stéphane was playing with Ekyan and pianist Alain Romans. Django (yes, the Django Reinhardt, because that’s who he was) suggested a form of musical association. Maybe those were his very words. Or maybe not, but what Django had in mind was definitely the creation of a small string-ensemble whose aim, essentially, was to play jazz. Django gave him a quick demonstration and Stéphane was so dazzled he almost couldn’t see straight... but he didn’t follow it up. So Django, never one to change his favourite habits, went off somewhere, probably in his caravan. When, exactly, did this event take place? Grappelli said it was at the end of 1930, but that might not only be too early, but also highly improbable for a number of reasons... and Stéphane was known for the eclipses in his memory. Was it perhaps the end of 1931? That sounds tricky, too: Django, down in the south of France, was listening to his first jazz records (Armstrong and Ellington, Joe Venuti and Eddie Lang…), or playing in Toulon and Cannes now and then with Louis Vola. You can get a glimpse of him in a film made in the spring of 1932 called Clair de Lune, another Diamant-Berger film that also had Blanche Montel in the cast... Could it have been the end of 1932, then? What a good idea! That would explain Grappelli’s momentary refusal: Grégor had come back. He was getting a new crew together and his plans included Grappelli...

Whichever year it really was, Django was in Paris in the winter of 1932/33, playing in the house-band at the “Boîte à Matelots”. In the course of 1934, Warlop frequently made use of his services for his own orchestra, and Django took part in most of Warlop’s record-sessions, including some where he accompanied a vocalist. That year, Grappelli and Django also found themselves in the same studio with musicians – almost the same ones, in fact, as those who played with Warlop – led by trombonist Guy Paquinet (alias Patrick). Most notable of all, however, were some remarkable events that took place during the summer of 1934: the “Hotel Claridge” in Paris was putting on some highly select tea-parties – they called them “thés dansants” – which featured another pair of Django’s old cronies who were still keeping busy, namely guitarist Roger Chaput and bassist Louis Vola. During the intermission, these two would have fun passing the time away by improvising over some of the American standards they worshipped... and that, believe it or not, is how Django’s “musical association” idea, (the “small string-ensemble”, if you like) came to be born. It was as unexpected as an improvisation... all they had to do was add a second guitar, Joseph Reinhardt, Django’s “little” brother, and off they went! Their road to fame – they were the Fab’ Five long before the Beatles were Four – was quickly paved by the recently-founded Hot Club de France, and the new string-group naturally became its emblem. Two of the Hot Club’s members, Charles Delaunay and especially Pierre Nourry, had both been won over to the cause, and they metamorphosed into conscientious impresarios. The group did a few tests on wax in September that year, but the Odéon firm, a circumspect publishing house, thought the result “too modern”. Ultraphone showed interest, but not before they’d haggled over the recording-fee... In his 1992 memoirs (With Only My Violin, Welcome Rain Publishers), Grappelli observes: “We got one hundred old francs each, one franc [in today’s money] for the recording. That was on December 2, 1934.” Stéphane probably forgot that 100 francs in 1934 didn’t have quite the same value as a single franc in the Nineties: with a hundred in cash in the mid-Thirties, he could have eaten out (in a reasonable restaurant), for a whole fortnight! As for December 2nd, it fell on a Sunday in 1934, and studios weren’t usually open for business on Sundays (especially for musicians who weren’t particularly famous); actually, December 2nd was the date of the first concert that the Quintette gave in public (at the “École Normale de Musique” in Paris), and that might have been the cause of the confusion. In all likelihood, that first session for Ultraphone probably took place on the 11th or 12th of December that year. Throughout the period 1935-39, concert-bookings, even abroad (in Italy, Scandinavia, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland or England), hardly ever lasted for any length of time, and musicians who toured in one band were often obliged to split up and look separately for gigs with other outfits. Basically, the fabulous Quintette du Hot Club de France, whose fame reached all the way round the world, was probably never a completely regular outfit...

After 1935, the Quintette started to record prolifically for companies that were bigger than Ultraphone: Decca, His Master’s Voice/Gramophone, and then Swing, the new label (distributed by Pathé Marconi) that was founded in 1937 by Charles Delaunay and Hugues Panassié: their sole aim was to record jazz whatever its shape. Most of those recordings were widely distributed abroad and, together with radio programmes that were aired internationally (the American continent included), they did much to contribute to the spread of the QHCF’s exceptional reputation. A promotional short-film was even made in the summer of 1938 for the band’s British tour – there may have been other “clips”, but only the one has come to light – and the tour was highly successful. The very professional English impresario Lew Grade took the group to Sweden and Norway, and a year later he took charge of them again, although the atmosphere was fraught with tension. Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 2nd 1939 and the guitarists and the bassist panicked. They rushed back across the Channel leaving Stéphane on his own in London, distraught and in poor health... Stéphane had always been unduly concerned about his health and this was almost the last straw: it was as if he’d aged from thirty to ninety overnight... Stéphane has gone on record as saying that by the time he recovered it was impossible for him to return across the Channel. Did he realise that there was a greater risk of a bomb falling on him if he stayed in London? Certainly not... because otherwise he’d have moved heaven and earth to get back to Paris. Sadly, several of his friends perished in London during the bombings... For the string Quintette du Hot Club de France, this, obviously, marked the beginning of the end. When Django returned to Montmartre he played in various places with different partners (either on leave or not in the Army anyway), and then when Paris became Occupied Territory the clarinet replaced the violin… Stéphane, still in exile, had no trouble at all finding work in a country where his reputation was solidly established. By December 1939 he was already the exceptional soloist with pianist Arthur Young‘s Swingtette, the group featured at the posh Piccadilly restaurant known as Hatchett’s. From 1941 onwards Stéphane led his own groups – they varied in size – and with two different formats he made a large number of records for Decca from the end of 1939 until 1945. As Stéphane had done in the past, the musicians in these bands often moved from one group to another, beginning with singer Beryl Davis, who set the example for guitarists Noël “Chappie” d’Amato and Jack Llewelyn, plus the remarkable pianist George Shearing (who went on to enjoy a nice career on the other side of the Atlantic), and also violinist and saxophonist Dennis Moonan, who went back to the Swingtette at Hatchett’s when Arthur Young was injured during an air-raid. Despite the presence of its illustrious guest-performer, the Swingtette was often criticised for not being a “real” jazz band so much as a group with a penchant for light music. It’s true that the “Novachord” that Young was playing at the time (a tired-sounding early synthesiser made by Hammond between ‘39 and ‘42), gave the group a vaguely “gimmicky” aura. Actually it was more often heard in sci-fi films... In short, it was the antithesis of the fiercely expressive sound unleashed by the defunct Quintette. The sides cut directly by the violinist leading his own bands are much more interesting, however, even if the tone is softer than that of the glorious pre-war period. Without Django and the sometimes rigid accompaniment provided by the Quintette, Stéphane had more opportunities to loosen up, to lighten his playing and discover his own “modern” style. There’s no doubt that the almost-constant presence of George Shearing alongside him was extremely helpful in this respect: it was no secret that Grappelli had a liking for harmony, and in his blind pianist he immediately found a partner who was almost as accomplished as the Gypsy.

As seen above, Django the Gypsy resurfaced in early 1946. He, too, had changed. Both musicians had undergone a subtle shift, a change that created a distance in their approach that would slowly grow and prevent any long-lasting return to the aesthetic of the past. Still, their reunion was a moving occasion and their new recordings were first-class. Due to their respective commitments, however, the old accomplices went no farther. Shortly afterwards, Django packed his bags – he was absent-minded enough to forget his superb cutaway guitar – and went off to America to play in Duke Ellington’s orchestra – or, to be more precise, alongside Duke –, an experience from which he emerged, somewhat disenchanted, in the course of 1947. In the autumn of that year, Grappelli, back on French soil for the first time in a while, recorded four sides for Swing with a gypsy, not the elder Gypsy but his younger brother Joseph, who wrote one tune. Stéphane would have to wait until 1954 before he recorded again under his name (making both 45rpm & 33rpm discs). In the interval he did record more Quintette sides for Swing (1948) and, with Django, there were the radio broadcasts made in France (1947) and Italy (1949) already mentioned. During that 1946-1954 period, Stéphane divided his time between England, where he still had fans, France (even though some disdain could be felt there), and in Italy, where he went to investigate his family-tree. He would add America and Australia to his list only later, but their time would come! He didn’t finally return to France until 1954. His first session, organised by the pianist Jacques (“Jack”) Diéval, his summer partner at the Escale in Saint-Tropez, was fitted into the Jazz aux Champs-Élysées series of releases. Grappelli next linked up – a very free association – with guitar-virtuoso Henri Crolla, a great admirer of Django Reinhardt (whose compositions he gleefully played, but took care not to copy), who was also Yves Montand’s regular accompanist (cf. the three volumes of the singer/actor’s complete recordings). With Crolla, Stéphane appeared often at the Club Saint-Germain where Django had been almost a fixture at the end. Crolla’s life, unfortunately, also ended prematurely (1920-1960), and his guitar followed that of Django after a mere seven-year interval. The good news is that Stéphane made several records with Crolla during that period, and the period was one of his best. At the time, Grappelli was recording mainly for Eddie Barclay, but he did find himself occasionally on records that bore the name of Decca or Véga. Such was the price of fame...

After those, Stéphane made records everywhere, for almost every firm that had an office in Paris, London, New York, Montreux or Copenhagen. He made so many records that the word “commonplace” started to appear. To clarify things: his duos with Menuhin (between 1972 and 1985) were produced by EMI, while his titles with Kenny Clarke turned up on RCA, MPS and Festival. And duelling violins weren’t his only other recordings: there were duets with delightful pianists (Earl Hines, Oscar Peterson, Martial Solal, Hank Jones, George Shearing, Raymond Fol…), not to mention his work with some subtle guitarists both famous and forgotten (Barney Kessel, Philip Catherine, Jimmy Shirley, Pierre Cavalli, Jimmy Gourley, Baden Powell, Larry Coryell, Joe Pass, Bucky Pizzarelli, Martin Taylor and, for years, Diz Disley…) There were so many that “Stéphane Grappelli and Friends” could have been a pretext for naming a festival. In the later years, after working with pianist Marc Hemmeler for a long time, Grappelli joined forces with Marc Fosset, an extremely modest guitarist and at the same time a very judicious choice... The many recordings Grappelli made after 1960 fall outside the scope of this set but, when you think about it, there is no reason to regret their absence: this selection represents the quintessence of his work. From the Sixties to the Eighties, Stéphane Grappelli played in every country that anti-communists refer to as “the free world”. He had an emotional vision of dear old Australia and a terrible memory of the fiendish Newport Festival of 1969 – even though he scored a personal bull’s-eye – because almost all the others who’d waved the “traditional jazz” flag there (beboppers included) had been lynched. Apart from that, he played in (numerous) festivals and led an otherwise peaceful existence playing upstairs at the “Toit de Paris” at the top of the Eiffel Tower, where jazz could only be tranquil... Montmartre was now much quieter. And then, with age, the violinist, though still frisky, finally stepped back, although even in 1996 he was still playing now and again when the occasion called for it. On December 1st 1997, if he’d been there to read it, he would have learned from a short AFP bulletin that he’d never play his violin or his piano again... because he’d passed away. The smiling, elegant old gentleman in a flowered shirt took his final bow in exactly the same place where he’d been born, at Lariboisière Hospital, still standing in Paris’ 10th arrondissement. He’d been round the world – Newport, Melbourne and Rome, and spent years in England – and he’d been summoned by both Norman Granz and Duke Ellington, but the 10th arrondissement, a stone’s throw from Montmartre, was still home. He’d often left it, but he’d always returned, the son of an Italian immigrant who wasn’t that welcome in his own country... decades had passed, and honours had been heaped on him, but Stéphane Grappelli had come full circle.

Every day, Grappelli had given thanks to God for His “invention” of jazz, so perhaps he was impatient to get up there and join a whole host of his old pals, musicians who’d been busy with their own eternal jam-session for years already: Django, Joseph, Vola, Warlop, Chaput, Ekyan, Combelle, Brun, Renard, all fellow-travellers, but also those he’d constantly admired: Tatum, Fats Waller, Satchmo, Bix, Coleman Hawkins, Duke, Joe Venuti, Eddie South, Stuff Smith… For as long as Stéphane was still around, it had been possible to imagine – naively, of course – that the legendary strings of the Quintette du Hot Club de France, the real QHCF of 1934-39, were out there somewhere, locked in the space-time continuum with a heart that still had a beat. When the heart of Stéphane Grappelli stopped beating, everyone knew that the gap in the continuum belonged to the realms of science-fiction. Post-war attempts to rebuild the band seemed to show that the old Quintette had lived its day; on December 1st 1997, it finally belonged to Eternity.

STÉPHANE GRAPPELLI

Discographical Notes