- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

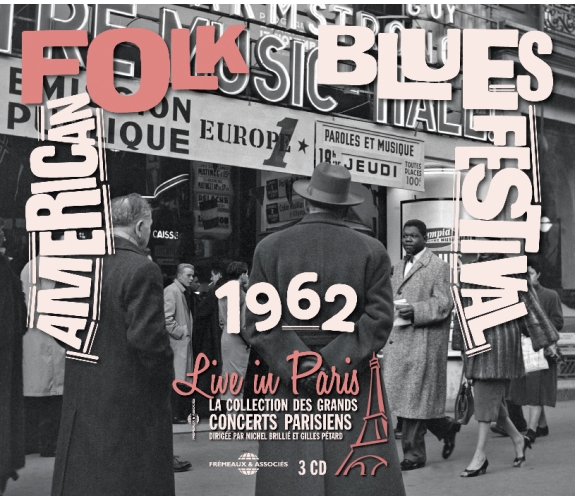

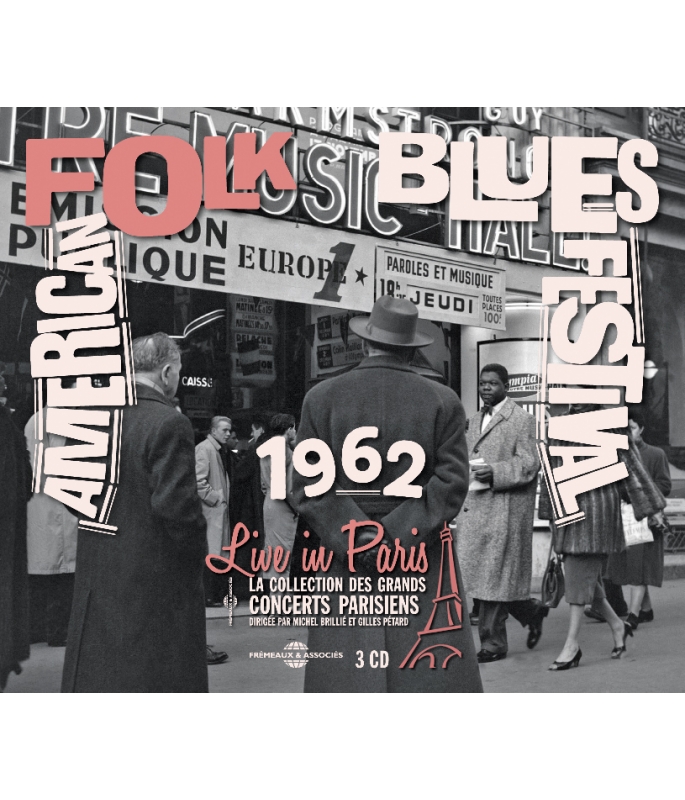

JOHN LEE HOOKER • T-BONE WALKER • SONNY TERRY & BROWNIE MCGHEE...

Ref.: FA5614

EAN : 3561302561424

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 9 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

JOHN LEE HOOKER • T-BONE WALKER • SONNY TERRY & BROWNIE MCGHEE...

For twenty years The American Folk Blues Festival was a legendary tour that undertook to spread authentic blues throughout Europe. In October 1962 the tour reached the Olympia in Paris, where the audience could hear the first French concerts by John Lee Hooker, Willie Dixon, T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. The concert sold out. It announced the Folk & Blues Revival wave that went on to sweep Europe & especially Britain in the mid-Sixties. Frémeaux & Associés, together with Body & Soul, are proud to make available to the public this never-released, complete 3CD set that also contains introductions, comments and the enthusiastic reactions of the audience. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period. Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : GILLES PÉTARD ET MICHEL BRILLIÉ

DROITS : BODY & SOUL LICENCIE A FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES.

CD1 :

MEMPHIS SLIM : FESTIVAL INTRODUCTION • JOHN LEE HOOKER : I’M IN THE MOOD - LET’S MAKE IT BABY - I DON’T WANT TO LOSE YOU - MONEY - THE RIGHT TIME - MEMPHIS SLIM INTRODUCTION • MEMPHIS SLIM : BAND INTRODUCTION - ROCKIN’ THE HOUSE • SHAKEY JAKE : HEY BABY - CALL ME WHEN YOU NEED ME - JAKE’S BLUES • WILLIE DIXON : TALKING ABOUT THE BLUES - NERVOUS - I JUST WANT TO MAKE LOVE TO YOU • MEMPHIS SLIM : BABY PLEASE DON’T GO - PINETOP’S BOOGIE WOOGIE.

CD2 :

MEMPHIS SLIM : HUGUES PANASSIÉ, SONNY TERRY & BROWNIE MCGHEE INTRODUCTION • SONNY TERRY & BROWNIE MCGHEE : I’M A STRANGER HERE - TALKIN’ HARMONICA BLUES - BORN AND LIVIN’ WITH THE BLUES - BABY, I GOT MY EYE ON YOU - JOHN HENRY • T-BONE WALKER : WOMAN YOU MUST BE CRAZY - MY OLD TIME USED TO BE - CALL IT STORMY MONDAY - YOU DON’T LOVE ME - T-BONE TALKS TO THE BOOERS • HELEN HUMES : MONEY HONEY - BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME - KANSAS CITY - SAINT LOUIS BLUES - MILLION DOLLAR SECRET • ENSEMBLE : BYE BYE BABY (FINALE).

CD3 :

MEMPHIS SLIM : JOHN LEE HOOKER INTRODUCTION • JOHN LEE HOOKER : EVERYDAY - LET’S MAKE IT BABY - THE RIGHT TIME - IT’S MY OWN FAULT - MONEY - MEMPHIS SLIM : BAND INTRODUCTION - ROCKIN’ THE HOUSE • T-BONE WALKER : MOANIN’ • HELEN HUMES : MONEY HONEY - BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME - KANSAS CITY - MARRIED MAN BLUES • ENSEMBLE : BYE BYE BABY (FINALE).

L’INTÉGRALE CÅZÎ COMPLÈTE DE L’OEUVRE D’ELMORE D

BLACK CREOLE, FRENCH MUSIC & BLUES 1929-1972

YOUNG AND WILD 1948-1949 & 1969 NOUVELLE...

THE BLUES- FATHER OF THE MODERN BLUES GUITAR 1929 -...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Festival IntroductionMemphis SlimInconnu00:01:081962

-

2I'm in the MoodJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:04:101962

-

3Let's Make it BabyJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:04:361962

-

4I Don't Want to Lose YouJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:05:011962

-

5MoneyJohn Lee HookerJanie Bradford00:03:221962

-

6The Right TimeJohn Lee HookerNapoleon Brown00:04:291962

-

7Memphis Slim IntroductionJohn Lee HookerInconnu00:00:421962

-

8Band IntroductionMemphis SlimMemphis Slim00:02:101962

-

9Rockin' the HouseMemphis SlimPeter Chatman00:02:521962

-

10Hey BabyShakey JakeJames D. Harris00:03:571962

-

11Call Me When You Need MeShakey JakeJames D. Harris00:03:141962

-

12Jake's BluesShakey JakeJames D. Harris00:02:111962

-

13Talking About the BluesWillie DixonWillie Dixon00:02:151962

-

14NervousWillie DixonWillie Dixon00:03:531962

-

15I Just Want to Make Love to YouWillie DixonWillie Dixon00:04:501962

-

16Baby Please Don't GoMemphis SlimJoe Lee Williams00:02:141962

-

17Pinetop's Boogie WoogieMemphis SlimClarence Smith00:04:091962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Hugues Panassié, Sonny Terry & Brownie Mcghee IntroductionMemphis SlimMemphis Slim00:01:391962

-

2I'm a Stranger HereSonny Terry, Brownie McgheeSonny Terry00:04:421962

-

3Talkin' Harmonica BluesSonny Terry, Brownie McgheeSonny Terry00:03:231962

-

4Born and Livin' With the BluesSonny Terry, Brownie McgheeBrownie Mcghee00:04:311962

-

5Baby, I Got My Eye On YouSonny Terry, Brownie McgheeSonny Terry00:03:291962

-

6John HenrySonny Terry, Brownie McgheeTraditionnel00:07:071962

-

7Woman You Must Be CrazyT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibeaux Walker00:05:361962

-

8My Old Time Used To BeT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibeaux Walker00:04:261962

-

9Call it Stormy MondayT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibeaux Walker00:04:091962

-

10You Don't Love MeT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibeaux Walker00:06:181962

-

11T-Bone Talks to the BooersT-Bone WalkerAaron Thibeaux Walker00:01:471962

-

12Money HoneyHelen HumesJesse Stone00:02:401962

-

13Baby Won't You Please Come HomeHelen HumesClarence Williams00:03:061962

-

14Kansas CityHelen HumesJerry Leiber00:02:231962

-

15Saint Louis BluesHelen HumesW. C. Handy00:02:341962

-

16Million Dollar SecretHelen HumesHelen Humes00:03:501962

-

17Bye Bye Baby (Finale)Helen HumesPeter Chatman00:10:191962

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1John Lee Hooker IntroductionMemphis SlimMemphis Slim00:00:551962

-

2EverydayJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:06:501962

-

3Let's Make it BabyJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:04:111962

-

4The Right TimeJohn Lee HookerNapoleon Brown00:05:341962

-

5It's My Own FaultJohn Lee HookerJohn Lee Hooker00:07:201962

-

6MoneyJohn Lee HookerJanie Bradford00:04:011962

-

7Band IntroductionMemphis SlimMemphis Slim00:02:511962

-

8Rockin' The HouseMemphis SlimPeter Chatman00:02:511962

-

9Moanin'T-Bone WalkerBobby Timmons00:03:401962

-

10Money HoneyHelen HumesJesse Stone00:02:431962

-

11Baby Won't You Please Come HomeHelen HumesCharles Warfield00:03:341962

-

12Kansas CityHelen HumesJerry Leiber00:02:351962

-

13Married Man BluesHelen HumesHelen Humes00:04:391962

-

14Bye Bye Baby (Finale)Helen HumesPeter Chatman00:10:331962

American Folk Blues fest FA5614

American Folk Blues Festival

LIVE IN PARIS

20 Octobre 1962

Le matin du Blues

Lu dans Le Monde, le 19 octobre 1962 : «?Deux concerts exceptionnels consacrés au blues traditionnel réuniront à l’Olympia, samedi 20 octobre, à 18 heures et à 24 heures, des musiciens dont les noms sont déjà bien connus des vrais amateurs français de jazz : Memphis Slim, John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Jump Jackson, Helen Humes et Shakey Shake (sic). A l’exception de Memphis Slim, ce sera la première fois que ces chanteurs se produiront à Paris.?»

Hambourg, Paris, Manchester – 1962

Ecce homo

Paris, Olympia, 20 Octobre, 18 heures. La salle est pleine à craquer. Hooker ouvre la soirée dans un costume bleu nuit. Les jambes sont légèrement écartées pour verrouiller la position. Il ne sangle pas une guitare acoustique comme à Newport, deux ans plus tôt, l’une des premières fois qu’il avait rencontré un public blanc. La Gibson à caisse claire est branchée sur le secteur mais l’ampli, bien tempéré, n’aspire jamais le grain du chant.

D’une voix profonde et charnue, avec une immobilité spectaculaire, il aligne cinq chansons sur des tempos assez rapides, «?In the Mood for Love?» ou la toute récente «?Let’s Make it Baby?». Celle-là, il vient de l’enregistrer dans un studio de Hambourg. Seul au fond de sa nuit, devant ces gens bizarres qui vous écoutent chanter comme s’ils assistaient à une pièce de théâtre, Hooker tient ses titres longtemps, avec beaucoup d’assurance. Il gobe le public parisien comme un gouffre dévorant, lui et eux, sonnés par le choc du face-à-face. Dans la salle, peu de spectateurs ont entendu parler de Hooker. L’affiche le présente pourtant comme la vedette d’un «?concert de rock’n’roll?», l’événement a fait l’objet d’une grosse promo.

Depuis le début du mois, cette gloire locale du ghetto dérive à travers des petits pays d’opérette, Allemagne, Autriche, Suisse, France. Ces jeunes blancs-becs ne dansent pas, mais il sait exactement ce qu’ils attendent de lui et il les sert. Du reste, les organisateurs de la tournée ne l’ont pas programmé par hasard en lever de rideau. Ils comptent sur son recueillement magnétique pour subjuguer un Olympia plein de jazzeux dubitatifs, dompter ces petits snobinards et les prédisposer à écouter les autres bluesmen de la tournée. Hooker fut «?le grand triomphateur de la soirée?», estiment les journalistes Demêtre et Chauvard, dans le compte-rendu que publie Jazz Hot deux mois plus tard. La veille encore, un administrateur du magazine apostrophait Jacques Demêtre : «?L’Olympia sera vide, ce genre de musique est dépassé. Qui peut avoir envie d’écouter ça ??»

La première tournée de l’AFBF, en octobre 1962, reste assez mystérieuse. L’itinéraire de la tournée conserve des zones d’ombre : on sait que les bluesmen venaient de Chicago, de Detroit et de Los Angeles, et qu’ils débarquèrent à Francfort le 3 octobre1. Ils se produisirent longuement en Allemagne, ainsi qu’à Vienne, Berne, Bâle, Zurich, Paris et Manchester. Quelques sources ajoutent des dates au Danemark et en Suède, Saar Murray évoque même une date singulière en Italie.

Faune d’une scène qui n’existe pas…

Mais l’énigme la plus épaisse tient au succès que rencontra l’événement. Sauf la soirée imprévue de Manchester, presque tous les concerts se jouèrent à guichets fermés, au grand étonnement des critiques de jazz. Ceux-là prédisaient aux organisateurs, Lippmann et Rau2, un échec cuisant. A peine estimaient-ils que l’AFBF rencontrerait un petit public en France, le pays qui, selon l’expression d’André Fanelli3, avait «?inventé le jazz?». En tout cas, l’étape parisienne de l’AFBF avait fait l’objet d’une présentation sur Europe 1 et d’un entrefilet dans Le Monde. Une campagne d’affichage sur les colonnes Morris et dans le métro prévenait les passants qu’un «?festival de rock’n’roll?» aurait lieu, avec John Lee Hooker en vedette.

Le samedi 20 octobre 1962, la météo fut conforme à la saison. A Paris, la pointe de mercure brilla jusqu’à 15 degrés. Des nuages bas et brumeux plafonnèrent toute la journée, déchirés de temps à autre par une éclaircie fugace, mais il n’avait pas fait de vent. Les radios du soir diffusaient surtout des enregistrements de concerts classiques et du jazz pour terminer le programme. Ceux qui possédaient un téléviseur pouvaient toujours bâiller devant la seule chaîne du pays. On y proposait une adaptation théâtrale d’«?Hélène?», avec Sylvia Montfort et Bernard Lavalette, puis un «?Rendez-vous avec Achille Zavatta?», et encore du jazz avant la mire.

A L’Œuvre, Pierre Fresnay, Pierre Dux et Danièle Delorme faisaient l’affiche de «?Mon Faust?», une pièce de Paul Valéry. Au Studio des Champs-Élysées, le jeune Sammy Frey donnait une lecture de Brecht, «?Dans la jungle des villes?». Dans les cinémas, on projetait «?Lucrèce Borgia?», «?Le gentleman d’Epsom?» ou, en sélection étrangère, «?Maciste contre les monstres?» au Comœdia, «?Maciste en enfer?» à La Fauvette. Fats Domino faisait le Palais des Sports. Le reporter du Figaro lui avait parlé de Johnny Hallyday, présent dans la salle. «?C’est qui, celui-là ??» A l’entr’acte, le journaliste avait demandé à l’idole des jeunes ce qu’il pensait du show. Un peu vexé : «?Je n’ai pas encore pu juger Fats Domino car une colonne me le cache?»… Et à l’Olympia, le public était invité à applaudir une charade à dix devinettes, neuf Noirs-Américains et un Yougoslave4.

Ce sont des collectionneurs de disques et des amateurs de jazz qui formèrent les premiers bataillons européens du blues. Lippmann et Rau avaient mis sur pied cette tournée de bluesmen pur-juke5 pour importer la preuve de ce qu’affirmaient, depuis quelques années, Jacques Demêtre ou Paul Oliver : le blues, éternel faire-valoir ethnologique du jazz, n’était pas un folklore qui s’était pétrifié dans les années trente, mais une famille de styles toujours dynamiques qui s’appréciait selon des critères différents de ceux du jazz. Le blues n’avait pas attendu que les cercles du jazz lui fissent la charité pour se régénérer dans le secret des ghettos. Le jazz recrutait ses ouailles parmi les agents de maîtrise et les techniciens, plus que chez des individus porteurs d’une culture académique classique. Ils constituaient un public jeune et pugnace qui trouvait, dans cet exutoire musical, les hymnes de sa révolte, avant que n’entrassent en scène Dylan et les Stones. Dans leur grande majorité, les amateurs de jazz étaient écœurés par l’obscurantisme des bluesmen, leur étroitesse intellectuelle, leur passivité politique et, dans l’expression de ce naufrage, leur pauvreté harmonique. Fritz Rau se souvient de la réaction très violente de Cannonball Adderley quand il apprit qu’une tournée 100?% blues se préparait en Europe. Le saxophoniste s’était indigné qu’on voulût «?oncle-tomiser?» le jazz.

Outre une petite phalange de jazzophiles bien disposés à l’égard du blues, plutôt Hot Club que be-bop, les premiers chalands du folk, encore très rares, avaient acheté eux aussi leur billet pour l’Olympia. Ils étaient passés d’Eddie Cochran à Leadbelly via Lonnie Donegan. Gérard Herzhaft, historien-musicologue du blues, se remémore cette époque6 : «?On considérait alors que le rock’n’roll n’était qu’une mauvaise copie du rhythm’n’blues, lui-même regardé comme un sous-genre mineur du jazz ! Je vivais sur les bords de la Manche. Toutes mes informations, mes émotions musicales venaient d’Angleterre (radios libres basées sur des navires ancrés hors des eaux territoriales, disques, jeunes amateurs britanniques rencontrés outre-Manche – certains deviendront de célèbres musiciens). Je ne venais donc pas au blues par le jazz, je n’étais d’ailleurs pas amateur de jazz et on me déniait presque le droit d’aimer le blues ! Je trouvais le blues proche du rock’n’roll et du folk, mais il dégageait davantage d’âme. Sonny Terry et Brownie McGhee avaient enregistré une version de «?John Henry?» qui me paraissait incroyablement plus animée et ‘habitée’ que certaines versions que je connaissais déjà.?»

Encore plus rares que les folkeux, quelques rockers s’étaient fait une vague idée de ce que pouvait être le blues, et l’entendaient comme une sorte de rock nègre. «?L’été des blousons noirs?» datait à peine de 1959. Les disques américains étaient très peu diffusés dans la France de Bob Azzam («?Fais-moi du couscous chéri?»), aussi les rockers français écoutaient-ils les Chaussettes Noires, les Pirates, les Pénitents et ne connaissaient pas Carl Perkins. Yves Montand chantait bien quelques pastiches de chansons de cow-boy, mais on ignorait jusqu’à l’existence de la country.

Plus inattendu : les cinéphiles. Les amateurs de denrées américaines trouvaient difficilement de la BD, de la science-fiction, du polar ou des films. Contrairement à ce qu’on imagine, le cinéma hollywoodien était peu distribué en France. Herzhaft : «?La société intellectuelle était idéologiquement dominée par le Parti communiste, mais la fascination pour le monde américain était considérable. Il y avait une forte demande pour tout ce qui venait de l’Amérique profonde. Des voyages en car étaient organisés vers Bruxelles certains week-ends, pour une cure de cinéma américain. On voyait cinq ou six séries-B qui ne sortaient pas en France. J’ai pu y rencontrer des gens comme Michel Marmin, Serge Daney, Alain Corneau… eux-mêmes familiers des AFBF. Ces concerts de l’Amérique profonde semblaient être un prolongement naturel et indispensable des films et des livres que nous vénérions.?»

Enfin, de nombreux étudiants et de nombreux curieux complétaient le cortège. Les concerts de musique américaine étant rares, tout était bon à prendre. La notion même de ‘salle comble’ doit être ramenée à l’échelle de l’époque. Fanelli : «?Quand un artiste attirait 300 personnes, on considérait que la salle était pleine ! Les Rolling Stones avaient rentré 1?500 personnes à Marseille, en 1965. On ne jouait pas encore dans des stades…?»

Herzhaft : «?Je suppose que le public de l’AFBF recherchait ce qu’on cherche toujours dans l’ailleurs : une part de rêve, une part de père jamais trouvé, une part de mère perdue, une part d’autre pour se compléter.?»

Les apéros de 18 heures et les soupers de minuit trente, le long du boulevard des Capucines, bruissaient des nouvelles d’Algérie. En mars, Paris et Alger avaient signé les accords d’Évian, le FLN avait cessé de mitrailler les commissariats parisiens et, soulagée, la capitale s’abandonnait à l’euphorie. Le ministère du Travail annonçait que 26 559 rapatriés avaient été reclassés. Les Français restés en Algérie voulaient croire que la situation se normalisait. 800 élèves, donvt 84 européens, faisaient leur rentrée au lycée français de Blida. La foule qui s’engouffrait dans le hall de l’Olympia ironisait peut-être sur la trajectoire de Ranger V qui allait encore manquer la lune de 483 kilomètres. À Berlin, le mur avait été mis en chantier l’année précédente et les diplomates préparaient le sommet des deux ‘K’, Kennedy et Khrouchtchev. Les investitures UNR de la Seine, en vue des législatives, étaient bouclées?; à Paris, M. Capitant affronterait donc M. Le Pen (Ind.). Et pendant ce temps, trois Nord-Africains s’emparaient de 40?000 NF dans une banque de Courbevoie, quatre malfrats assommaient à coups de crosse le directeur d’une coopérative laitière d’Ivry et lui soutiraient 7?000 NF.

Un samedi nuageux à Paris

Le 18 octobre, la blueswoman et les bluesmen de l’AFBF donnent leur dernière date allemande à Hambourg et enregistrent, après le concert, l’album-souvenir de la tournée aux studios Deutsche Grammophon de la ville. Lippmann et Rau produisent la séance pour le label Brunswick, le seul à avoir manifesté un peu d’intérêt pour ce genre de document. C’est à cette occasion que John Lee Hooker grave «?Shake It Baby?» qui va faire un hit retentissant en France et en Allemagne l’année suivante, atteignant les 100?000 exemplaires vendus. Herzhaft, citant le journaliste Sacha Reins : «?Shake It Baby?» fut : «?l’un des premiers tubes à émerger grâce au réseau des discothèques en France?». Horst Lippmann : «?Nous avons produit le premier disque de l’AFBF. Nous avons payé et n’avons rien perçu en retour?». Hooker : «?J’avais fait un gros hit en Europe, je n’ai jamais rien touché dessus?».

Le 19 octobre, les musiciens de la tournée atterrissent en France. Le soir, ils sont à Paris et donnent un «?bœuf mémorable?» aux Trois Mailletz, un club sis rue Galande près de Notre-Dame. «?Le trompettiste Bill Coleman s’y produisait de façon permanente, se souvient Demêtre. Beaucoup de musiciens de passage venaient y faire un bœuf. Memphis Slim et Champion Jack Dupree y étaient régulièrement programmés. Un soir on y a vu Big Bill Broonzy qui jouait avec l’orchestre à l’affiche. Ça se passait en sous-sol. Les musiciens étaient engagés par une petite dame blonde, très énergique, Mme Calvet. Elle avait aménagé, en annexe, une sorte de petit musée, une chambre des tortures… Mme Calvet collectionnait les instruments de torture du Moyen âge !?»

Hooker a reconnu Demêtre, le journaliste français qui l’avait interviewé trois ans plus tôt à Detroit dans la boutique de Joe Van Battle. Il a même conservé un numéro de Jazz Hot de 1959 dans lequel Demêtre publiait un portrait du bluesman. Le 20 octobre, Jacques Demêtre et son épouse déjeunent vers Pigalle, chez Haynes, en compagnie de John Lee Hooker et de Shakey Jake. On y mange de la bonne cuisine du sud des Etats-Unis. Hooker est ravi d’être à Paris. Il s’est fait à l’idée qu’en Europe les restaurateurs suspendent le service après 14 heures, et qu’il est difficile de trouver quelque chose à manger en pleine nuit.Le premier des deux concerts de l’Olympia eut donc lieu à 18 heures. Hooker en ouverture, Slim et Dixon pour l’intermède, puis l’harmoniciste Shakey Jake pour trois titres seulement. Jake se retire sur un «?salut musulman?». Dixon, Slim, Jump Jackson reprennent la lumière de la rampe pour quelques titres, dont «?Nervous?» : le contrebassiste se moque d’un bègue, peut-être un clin d’œil vachard à l’adresse de Hooker qui bégayait. Entr’acte. Le duo Sonny Terry et Brownie McGhee démarre la deuxième partie du concert. Puis l’incident T-Bone Walker, qui atteste que le public de l’Olympia n’était pas un ectoplasme en perpétuelle adoration.

L’homme de Los Angeles entre en scène, soutenu par Dixon, Jump, et un excellent pianiste de Zagreb nommé Davor Kajfes. T-Bone se livre au genre de pantomime qui fait toujours l’unanimité dans les jukes et les dancings qu’il écume aux Etats-Unis. Il danse, exécute le grand écart sans cesser de jouer, guitare derrière la nuque, et ne se départit pas d’un large sourire dentu «?qui le fait ressembler à Fernandel?». Des huées incrédules fusent du fond de la salle. Walker : «?What mean these ‘wouhouhou’ ??». Qui le siffle ? Des amateurs de jazz moderne, outrés par un jeu scénique qu’ils assimilent aux gesticulations du rock. Demêtre : «?Ces jeunes gens, influencés par les écrits de Panassié contre la guitare électrique soi-disant imposée aux bluesmen par les Blancs, ont profité de l’occasion pour manifester contre T-Bone Walker?».

Le lendemain à Manchester, Walker pliera le public anglais avec les mêmes acrobaties, mais c’était déjà un autre public. Helen Humes conclut, et la soirée magique s’achève sur un «?final d’une belle tenue, totalement exempt des pitreries d’un Hampton?». Ils quittent la scène lentement, sous les ovations.

Le deuxième concert débute à minuit et demi, un rendez-vous tardif très étonnant pour l’époque. Les mêmes dans un ordre légèrement modifié (Shakey Jake et Terry-McGhee ont permuté), un Olympia toujours aussi bondé, T-Bone a attiédi ses ardeurs gymniques et la salle ne s’est offusquée de rien. Demêtre s’offre une revanche sur ses détracteurs jazzo-rigides et bluesophobes : «?Ces manifestations marquent un tournant important, et même décisif, dans la compréhension de cet art en France. Pour la première fois, en effet, le blues authentique sort des clubs d’initiés et s’installe en position de force dans une des plus grandes salles parisiennes.?» Gérard Herzhaft : «?A partir de cet instant, le blues sort définitivement du cadre étroit et réducteur du jazz?».

Un dimanche d’automne à Manchester

Willie Dixon : «?C’est pas Lippmann qui a organisé la tournée anglaise, mais un autre tourneur. Depuis, il a quitté les affaires et il me doit toujours du blé !?». Les deux concerts épiques de Manchester qui se jouèrent, le lendemain de l’Olympia, au Free Trade Hall, faillirent ne pas avoir lieu. Outre-manche, Lippmann et Rau ne trouvaient aucune salle qui acceptât de recevoir leurs artistes, les gérants leur soutenaient que le blues n’intéressait personne ici, qu’une telle aventure serait ruineuse pour tout le monde. Fritz Rau entendit même un officiel londonien lui objecter : «?Nous avons un très bon orchestre philharmonique qui remplit convenablement nos théâtres, nous n’avons pas besoin de bluesmen pour cela?». Finalement, un certain Paddy McKiernan récupéra la caravane et, en cheville avec le Melody Maker, prit le risque d’inscrire une date à Manchester, au fin fond de cette province anglaise où aucun Londonien n’était censé se hasarder. Ici, l’événement n’avait bénéficié d’aucune réclame, la dernière date de la tournée avait été arrachée in extremis et montée dans une certaine improvisation, la nouvelle s’était colportée de bouche à oreille, à la faveur de petites annonces déposées par les aficionados dans le Melody Maker, Jazz News, ou sur la devanture des disquaires. D’ores et déjà, l’AFBF n’appartenait plus à Lippmann, Rau ou McKiernan, ni même au monde du jazz, mais à la jeunesse du rock’n’roll. Les futurs contingents du swinging London ne voulaient pas croire qu’en une seule soirée on pût applaudir autant de bluesmen fantasmatiques, dont on idolâtrait les disques mais qui se produisaient toujours à l’autre bout du monde.Ainsi, le pays d’Europe où le blues bourgeonnait avec le plus d’impatience, du fait de la langue, de la présence de GI’s noirs, d’émetteurs pirates, un pays qui disposait déjà de prototypes musicaux comme le skiffle, de consciences comme Alexis Korner, d’un circuit embryonnaire de scènes dégagées de la férule du jazz, un pays qui comptait déjà une population appelée l’adolescence, où, pour le blues, l’invitation semblait la plus naturelle, se révélait être également le pays d’Europe le plus indifférent à la revue noire de Lippmann et Rau.

Paul Jones, qui sera bientôt le chanteur et l’harmoniciste du groupe Manfred Man, était venu d’Oxford en stop. Dave Williams, un collectionneur de disques, avait loué un minivan et roulé toute la journée depuis Londres. À son bord, quatre anonymes : Jimmy Page, Brian Jones, Keith Richards et Mick Jagger. Les cinq fans étaient entrés à Manchester le samedi soir, alors que John Lee Hooker scotchait l’Olympia. Ils passèrent la nuit comme ils purent, dans une sorte de cité U, en attendant le concert du lendemain.

Le Free Trade Hall est une énorme bâtisse du XIXe siècle posée sur des arches trapues, symbole de la révolution industrielle, bombardée pendant la guerre, reconstruite en 1951. Sa façade sans grâce est arrangée avec un classicisme imposant et sinistre. Le gérant a prévenu McKiernan : à 22?h?30 au plus tard, l’endroit doit être libéré.

Plusieurs rangées de fauteuils sont inoccupées. Les conditions dans lesquelles s’est préparé l’événement expliquent largement cet émaillage. C’est encore John Lee Hooker qui ouvre pour ses camarades. À cause du couperet de 22?h?30, les organisateurs ont abrégé la durée des concerts, Hooker n’a plus droit qu’à deux chansons. Par contre le duo Terry-McGhee, qui avait triomphé à Londres en 1958, est autorisé à se goberger sur scène trois fois plus longtemps que les autres. Lorsqu’Helen Humes monte sur les planches, Memphis Slim est remplacé par un pianiste du coin qui scande du 12-mesures, le nez dans une partition. Quant à T-Bone Walker, «?on n’avait pas assisté à un tel concentré de bouffonnerie depuis la venue de Lionel Hampton, note le Jazz Monthly. Mais quel swing fabuleux ! (…) Le dynamisme de ses inflexions et de ses rythmiques en font un musicien supérieur à n’importe quel guitariste de jazz contemporain.?»

Ce triste dimanche soir d’automne, les deux héros du Free Trade Hall furent Hooker et Walker. Malgré la salle clairsemée, sur cette grande scène sans intimité, les bluesmen se surpassèrent et la ferveur extraordinaire du public compensa la modicité du remplissage. La foule investit la scène pendant le final avec une jubilation qui frisait l’émeute. 22?h?30. La salle s’allume. Un baffle canonne ‘God Save The Queen’. Le responsable du Hall a cru bon de passer ce disque pour accélérer l’évacuation. En coulisses, Shakey Jake s’entretient avec le secrétaire de la Jazz Society de l’université de Londres. Un jeune homme les interrompt, un harmonica dans la paume : «?Vous me laisseriez-vous montrer ??». Shakey Jake : «?Eh, tu es déjà une véritable star, toi !?» Le jeune homme se nomme Mick Jagger.

Christian Casoni

Bluesagain.com

Un dernier mot : l’enregistrement public de ce premier American Folk Blues Festival est resté introuvable pendant 52 ans. Jusqu’à ce jour de décembre 2014, où je me suis retrouvé un dimanche dans une maison de campagne de l’ouest de l’Ile-de-France, dans un sous-sol digne de Las Vegas, avec billard et juke-box vintage. Là, dans un étroit couloir reliant deux parties distinctes de la maison, des centaines de boîtes de bandes magnétiques Sonocolor ou Agfa, avec annotations d’époque. Parmi tous ces trésors, 7 bobines en parfait état : l’AFBF du 20 Octobre 1962. Pour moi, la boucle est bouclée. Daniel, merci.

Michel Brillié

L’enregistrement du premier concert est intégral, avec les présentations, les commentaires, et les réactions du public.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. Sauf Memphis Slim, qui s’est établi à Paris en novembre 1961.

2. Les Allemands Horst Lippmann et Fritz Rau fondèrent l’American Folk Blues Festival (1962-1982). Horst, batteur de jazz, et Fritz, avocat / patron de club, étaient des producteurs de l’émission Jazz Gehört und Gesehn, que diffusa la télévision de Baden Baden (Südwestrundfunk) entre 1955 et 1972. Ils montèrent l’agence de spectacles Lippmann & Rau et coproduisirent, avec Norman Granz, les tournées Jazz at the Philharmonic. Avec Willie Dixon, Lippmann & Rau a organisé la série des festivals de blues qui fit découvrir, au public européen, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, Little Brother Montgomery, J.B. Lenoir, Lonnie Johnson, Victoria Spivey, Big Joe Williams, Sleepy John Estes… Ils ont aussi créé le label L+R qui sur lequel furent gravés les témoignages sonores de l’AFBF.

3. André Fanelli : musicologue lié à Jazz Hot et Soul Bag. Il a organisé des concerts en France, et rencontré tous les jazzmen et bluesmen qui ont posé un jour le pied sur l’Hexagone durant les années 60.

4. Il s’agit de Davor Kajfes, qui prend la place de Memphis Slim au piano pour accompagner les sets de T-Bone Walker et Helen Humes.

5. Un juke (ou juke joint, honky-tonk) est, dans la langue populaire noire-américaine, un établissement public combinant musique, danse, jeu et alcool. Situés dès les années trente dans des zones rurales, ces bars improvisés étaient fréquentés par les travailleurs noirs après une dure journée de labeur. Certains jukes vendaient aussi de l’alcool de contrebande. Les jukes se sont développés également dans les villes des États-Unis et ont propagé l’esprit du blues jusqu’au milieu des années 70.

6. Gérard Herzhaft est l’auteur de l’Encyclopédie du Blues (Éditions Fayard) l’ouvrage de référence sur le blues, et de nombreux livres sur la country, l’harmonica et l’histoire de la musique américaine. Gérard Herzhaft a sillonné les États-Unis et rencontré les plus grands bluesmen vivants.

American Folk Blues Festival

LIVE IN PARIS

20th Oct. 1962

The Morning of Blues

Excerpt from an article of October 19, 1962, in Le Monde, the Paris daily newspaper: “Saturday October 20, at 6:00PM and 12:00AM, two special concerts dedicated to rural and traditional blues music will bring together on stage musicians who are already well known among jazz fans in France. They are Memphis Slim, John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Jump Jackson, Helen Humes and Shakey Shake (sic). Except for Memphis Slim, all those artists will appear for the first time in Paris.”

Hamburg, Paris, Manchester – 1962

Ecce homo

Paris, the Olympia Theater, October 20, 6:00PM. It’s a full house. John Lee Hooker in a dark blue suit is the opening act. He stands with his legs slightly apart to steady his posture. Unlike at the Newport Festival, he doesn’t sport an acoustic guitar, when he then performed for the first time in front of a white audience. His slim-body Gibson is plugged in but the amp doesn’t overpower his singing.

With his deep and full-bodied voice, he sings five medium up-tempo songs back-to-back, like ‘In the Mood for Love’ or his latest, ‘Let’s Make it Baby’, which he has just recorded in a Hamburg studio. He stands there alone as in the midst of a deep dark night, in front of all those people listening in a respectful silence. Hooker keeps his ground firmly, stretching his songs with confidence. He gobbles up the Parisian crowd like a giant devouring hole, both knocked down by the confrontation. In fact, few people have ever heard of Hooker. The show poster had him billed as the star of a ‘Rock n’ Roll’ concert, with a heavy promo plan.

Since the beginning of the month, this ghetto celeb has been drifting through operetta-like countries – Austria, Switzerland, Germany, and France. The white boys there don’t dance, but John Lee knows exactly what they expect from him and he delivers. The tour promoters have made him the opening act for a reason. They rely on his magnetism to conquer the Olympia house full of skeptic hard core jazz fans, and tame these little snobs so that they will listen to the other blues artists on the program.

Hooker was ‘the victorious hero of the evening’ according to Jazz Hot Magazine reviewers Demêtre and Chauvard in their article published two months later. Just the day before the show, a magazine exec had told Demêtre that ‘the house would be empty. This type of music is out. Who the hell wants to listen to this?’

This first American Folk Blues Festival Tour of October ’62 remains somehow mysterious. There are still some uncertainties as to its itinerary. We know that the bluesmen came from Chicago, Detroit or Los Angeles to land at Frankfurt Airport on October 3rd1. Then followed a lengthy series of concerts in Germany, Vienna, Bern, Basel, Zurich, Paris and Manchester. Some sources mention gigs in Denmark, Sweden. The English music journalist Charles Shaar Murray even speaks of one in Italy.

The fauna of a non-existent scene

However, the most intriguing enigma is the success of the event. Apart from the last-minute planned Manchester evening, all the concerts were sold out, to the astonishment of jazz critics, who had predicted tour promoters Lippmann and Rau2 a severe flop. They assumed that AFBF would be mildly popular in France, the country that had ‘invented jazz’, according to music expert André Fanelli3. In fact, the Parisian stopover had been reviewed on the French radio Europe N°1 and in a short item in Le Monde. A billboard campaign was announcing a ‘rock n’ roll festival’ with John Lee Hooker as the star.

On Saturday October 20th, the weather was seasonal. The temperature went up to 15° Celsius in Paris. The sky was mostly overcast with clouds throughout the day, with an occasional clearing and no wind.

Evening radio broadcasts consisted mainly of classical music and jazz to conclude the programs of the day. The few owners of a TV set could doze in front of the only channel available then. The listings included a light theater play and a circus act. Paul Valéry’s Faust was playing at the Œuvre Theater while a reading of Bertold Brecht was held at the Studio des Champs Elysées. Fats Domino starred at the Palais des Sports. A Figaro newsman had asked the rotund singer what he thought of Johnny Hallyday, France’s new rock idol. ‘Who’s that?’ was Fat’s reply. Then during intermission, the same reporter had approached Johnny for his impression of Domino’s talent. ’I can’t really tell because my seat is behind a pillar’ answered a piqued Hallyday. And at the Olympia Theater, the French audience was facing a puzzle with ten pieces, nine Afro-Americans and a Yugoslavian4.

European record collectors and jazz fans were the first to appreciate blues music. Lipmann & Rau had put together this initial blues tour to prove what Jacques Demêtre or Paul Oliver had been saying for years: blues, considered by many as just an ethnic side product of jazz, was not a piece of folklore that had been frozen in the thirties, but a thriving group of various styles that were considered according to different criteria than those of jazz music. Blues had not waited for the blessing from jazz circles to grow in the depth of the ghettos.

Jazz found its supporters among middle managers and technicians more than academia. They formed a youthful and passionate audience who found in this type of music the seeds of their revolt, before the Stones and Dylan took over. For the vast majority, jazz fans were disgusted by blues fans’ narrow-mindedness, by their political passivity and their poor harmonics. Fritz Rau recalls how violently Cannonball Adderley reacted when he heard of the 100% blues tour in the works. The saxophone player was adamant against “Uncle-Toming” jazz.

Aside from a small group of jazz fans who also liked blues, some of the early aficionados of folk music had bought seats for the Olympia Theater shows. They had gone from Eddie Cochran to Leadbelly via Lonnie Donegan. Gérard Herzhaft, a French blues musicologist recollects this era5: “People thought then that rock n’ roll was just a bad copy of rhythm n’ blues, which itself was regarded as a minor genre of jazz! I used to live on the coast of the Channel. The bulk of my musical information and emotions came from England with the pirate radio stations, and records from young British fans – some of whom became famous musicians. I had not therefore been introduced to blues by the way of jazz, in fact I did not like it, and I was denied the right to like blues! I thought blues to be closer to rock n’ roll and folk music, with a lot more soul. Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee had recorded their rendition of ‘John Henry’ which I deemed to be far more spirited than the other versions of the song I already knew.”

There was also a small group of rockers – even smaller than the folk group – that had a vague idea of what blues was about, and considered it as some kind of “negro” rock. France had been exposed to their local Teddy Boys riots only a couple of years ago. Few American songs were aired on the radio, so the French rockers listened to local French rock groups, and had never heard of singers like Carl Perkins, for instance. Yves Montand had a couple of cow boy tunes in his repertoire, but nobody knew a thing about country music.

Another odd group was also attending the first blues night in Paris. These were the American movie buffs, which had a hard time finding comics or science fiction, or films, as the Hollywood films were poorly distributed in France. Herzhaft remembers: “The intellectual society was ideologically dominated by the Communist Party, but there was still an enormous interest for the American world. There were organized week end tours to Brussels to get a glimpse at American movies. We went there to watch a half dozen of hard-to-find B movies. I met some movie professionals like Alain Corneau who were all AFBF regulars. These concerts from deep-down America seemed to be the natural and essential continuation of our beloved American movies and books.”

And lastly a great number of students and onlookers made up the rest of the audience. American music concerts were scarce, anything was worth grabbing. Even the conception of a ‘full house’ has to be scaled down to early sixties standards. Says Fanelli: “When somebody pulled 300 people in the house, we thought the place was jammed! The Rolling Stones had got 1.500 persons in Marseilles in 1965. Nobody ever played stadiums…” Also: “I suppose the AFBF crowd was looking for something you always find elsewhere: part of a dream, part of a never-found father, part of a long-lost mother, and a part of something else to fulfill oneself.”

Parisian happy hours and late night dinners were full of news from Algeria. In March of the same year, Algiers and Paris had signed the Evian agreement, the Algerian National Front of Liberation had stopped shooting at Parisian police stations and relieved inhabitants were exhilarated. 56.559 repatriated Algerians had set foot on the homeland and found work. Those that had stayed behind believed in a normalized situation. The people that crowded the lobby of the Olympia Theater that night might have made fun of the inaccurate flight path of the Ranger V rocket, about to miss the moon by 483 km. In Berlin, the wall had been started the year before, and the two ‘Ks’, Kennedy and Khrushchev, were getting ready for their summit meeting.

Cloudy Saturday in Paris

On October 18th, the itinerant bluesmen (and woman) of the AFBF performed in Hamburg for the last time in Germany; they also recorded, after the concert, the souvenir album for this tour at the local Deutsche Grammophon studios. Lippmann and Rau are the session producers for the Brunswick label, the only company to express some kind of interest for this type of document. On this occasion John Lee Hooker records ‘Shake It Baby’, a song to become the following year a major hit in Germany and France, with over 100.000 sales. Herzhaft quotes music journalist Sacha Reins saying: “‘Shake It Baby’ was one of the first records to emerge from the club circuit in France” Horst Lippmann: “We produced the first AFBF album. We payed for it, and got nothing in return.”, and Hooker: “I had this huge hit in Europe, but I never got a cent from it.”

On October 19th, the musicians landed at Paris airport. That same night, they had a free schedule and ended up in a “memorable jam-session” at the Trois Mailletz, a Parisian club near Notre Dame Cathedral. Demêtre remembers it well: “Trumpet player Bill Coleman was a regular feature there, and a lot of visiting musicians would come and jam. Memphis Slim and Champion Jack Dupree were also regulars. One night Big Bill Broonzy even played with the house band. It took place in a basement. The owner was a small energetic blond lady, Madame Calvet. In another room, she had put together a small museum, a kind of torture chamber… Madame Calvet collected torture instruments from the Middle Ages!”

At the club, Hooker has identified Demêtre as the French newsman who had interviewed him three years before in Joe Van Battle’s shop in Detroit. He had even kept the 1959 Jazz Hot Magazine issue where Demêtre had published his piece about the singer. The next day, October 20th, Demêtre and his wife were having lunch with John Lee Hooker and Shakey Jake in Pigalle at Haynes’s well known American restaurant. The fare was definitely soul food there, and Hooker was thrilled to be in Paris. He had become accustomed to the fact that no food was served in Europe after 2:00PM and that it was hard to find something to eat in the middle of the night… The first of the two AFBF concerts started at 6:00PM. Hooker was the opening act, then Slim and Dixon followed by Shakey Jake on harmonica for three numbers only. Jake exited the stage with a “Muslim salute”. Dixon, Slim and Jump Jackson stepped back in the spotlight for a few songs, among which ‘Nervous’ in which the bass player was making fun of a stammering individual, perhaps a poke at Hooker who had a speech impediment. Then came the intermission. The second part of the concert started with Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, followed by T-Bone Walker and the booing incident that attests that the Olympia audience is not in full passive reverence of the artists.

As Walker, from Los Angeles, enters stage, his backing band includes Dixon, Jump and a great pianist from Zagreb by the name of Davor Kajfes. T-Bone then gets into a miming act that is always popular in the various juke joints and dance halls he is familiar with in the U.S. He dances, does splits while playing with a big grin, his guitar behind his back. Incredulous booing starts in the back of the house. Walker fights back: “What mean these ‘wouhouhou’ ?”. Who’s really booing? Some hard core modern jazz fans, incensed by a stage act that for them looks exactly like rock n’ roll. Says Demêtre: “These young cats were influenced by [conservative] Hugues Panassié’s articles against amplified guitar he believed to be imposed by white people to the blues singers. So they took the opportunity to heckle T-Bone Walker.” The next day in Manchester, Walker got the English audience on his side with the same acrobatics, but they were already aware of blues. Helen Humes wraps up the first show and ends with a “well behaved finale, without the clown-like demonstrations of a Lionel Hampton.” Slowly, the whole gang leaves the stage under thunderous applause.

The second show started at 12:30AM, a very late schedule by the standards of the times. The line-up has been slightly modified, with Terry-Mc Ghee before Shakey Jake. The Olympia house is just as packed as for the first show. T-Bone has toned down his gymnastics, and no one complains about it. Newsman Demêtre gets his revenge on his jazz/blues purist foes: “These shows are an essential turning point for this art in France. For the first time, blues gets out of special clubs and becomes a major force in one of the largest concert halls in Paris.” And as musicologist Gérard Herzhaft points out: “From then on, blues was finally out of the narrow and reducing frame of jazz music.”

Fall Sunday in Manchester

Willie Dixon recalls that “It wasn’t Lippmann who got the English tour together, but another promoter. Since then, this guy has now left the business but he still owes me some dough!” The two cult Manchester shows at the Free Trade Hall, the day after the Olympia gigs, almost did not happen. Lippmann & Rau were not able to secure a hall that would take their artists. The English owners were certain that blues wouldn’t draw a crowd, and that they would lose their shirts. Fritz Rau even had a talk with some London official who objected:“We have a very good philharmonic orchestra that fills our concert halls quite decently, we really do not need any blues person for that purpose.” At the end, an agent named Paddy McKiernan took over, and, supported by the Melody Maker trade publication, risked a show in Manchester, deep in the British countryside where no decent Londoner would dare to travel.

In Manchester, the concert had received no advertising. The final gig of the European tour had been set up in a hurry and somewhat improvised. There was word-of-mouth promotion, some classified ads in the Melody Maker and posters in local record shops. AFBF was now out of the hands of Lippmann, Rau, McKiernan, or even the jazz world: it now belonged to the rock n’ roll younger crowd. The future Swinging London set couldn’t believe that they were going to cheer for so many fantastic bluesmen in the same evening, the artists whose recordings they revered – but who were always performing in some dark corner of the world.

Strangely enough, England, the European country where blues was at a bubbling point, was also the least receptive to Lippmann & Rau’s black revue. In spite of a common language, of black GI’s in various harbors, of pirate radio stations, of Skiffle music, of a local fresh club scene, or of a strong emerging teenage group…

Paul Jones, who would later become the singer/harmonica player for Manfred Mann’s group, hitchhiked all the way from Oxford. A record collector named Dave Williams had rented a minivan and drove the entire day from London. Sitting next to him were four unknown chaps, Jimmy Page, Brian Jones, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. The five blues fans had arrived in Manchester Saturday night, when John Lee Hooker was mesmerizing the Olympia house. They crashed some local student room for the night to await the following day concert.

The Free Trade Hall is a large 19th century stout building, a symbol of the industrial revolution that was bombed during World War II and rebuilt in 1951. Its dull front has an impressive and sinister classic look. The owner had warned McKiernan: the place had to be empty by 10:30PM.

When the show started, several rows of seats were still unoccupied. That was easily understandable, given the conditions under which the event was set up. Once again, John Lee Hooker opened the line-up. Because of the short time schedule, he only sang two songs. On the other hand, the Terry-McGhee duet was allowed to sing three times as much, this due to their previous success in London in 1958. When Helen Humes stepped on stage, Memphis Slim had been replaced by a local pianist playing from a score. Jazz Monthly gave this review of T-Bone Walker’s performance: “We had not witnessed such clowning since Lionel Hampton’s coming to England. But what a fantastic sense of swing! (…) His dynamism and rhythm make him surely a better musician than any contemporary jazz guitarist.”

On that grey fall Sunday evening, the two heroes of the Free Trade Hall were definitely Hooker and Walker. In spite of a scarce attendance, of a too-big cold stage, the bluesmen excelled in their art, and the overwhelming enthusiasm of the audience made up for its limited number. The crowd got on stage during the finale with a glee on the fringe of rioting.

10:30PM.The lights go up. The P.A. system blares out ‘God Save The Queen’. The manager thinks this will speed up the hall’s evacuation. Backstage, Shakey Jake is talking to the secretary of the University of London’s Jazz Society. A young man interferes, with a harmonica in his hand. “Can I show you?” Shakey Jake is amused: “Wow, you guy must be a real star!” The young man’s name is Mick Jagger.

Christian Casoni

Bluesagain.com

(Adapted and translated by Michel Brillié)

A final word. The live recording of this first American Folk Blues Festival in 1962 was nowhere to be found for 52 years. Until that particular Sunday in December 2014, when I found myself in a country house West of Paris, in a Las-Vegas-like basement, complete with pool table and vintage juke-box. There, in a narrow corridor separating two distinct parts of the building, stood hundreds of boxes of Sonocolor or Agfa magnetic tape, with hand-written notes. Among all those treasures lay seven reels in mint condition: the AFBF of October 20, 1962. I knew then I had come full circle. Daniel, thanks.

Michel Brillié

This recording is unedited with artists’ commentaries and audience reactions.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2015

1. Except Memphis Slim, who had moved to Paris since November 1961

2. German-born Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau are the founders of the American Folk Blues Festival (1962-1982). Horst was a jazz drummer and Fritz a lawyer/ club owner. They were the producers of TV show Jazz Gehört und Gesehn, aired on Baden-Baden’s Channel (Südwestrundfunk) from 1955 to 1972. They put together the Lippmann & Rau concert agency and co-produced with Norman Granz the Jazz at the Philharmonic tours. Along with Willie Dixon, Lippmann & Rau organized the series of Blues Festivals that introduced to European audiences Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, Little Brother Montgomery, J.B. Lenoir, Lonnie Johnson, Victoria Spivey, Big Joe Williams, Sleepy John Estes… They also created the L+R label to record the various AFBF concerts.

3. André Fanelli is a musicologist and writer for Jazz Hot or Soul Bag. He also was a concert promoter in France, and has met each and every bluesman that set foot in the country in the sixties.

4. He was Davor Kajfes, who filled in for Memphis Slim during T-Bone Walker and Helen Humes’s sets.

5. Gérard Herzhaft is the author of ‘l’Encyclopédie du Blues’ (Editions Fayard), the French reference book on blues music, and numerous other works on country music, harmonica or the history of American music. Gérard Herzhaft has traveled extensively in the U.S. and met the most important bluesmen alive.

-CD1-

?1. Festival Introduction 1’08

?2. I’m in the Mood (John Lee Hooker / Bernard Besman) 4’10

?3. Let’s Make it Baby (John Lee Hooker) 4’36

?4. I Don’t Want to Lose You (John Lee Hooker) 5’01

?5. Money (Janie Bradford / Berry Gordy Jr) 3’22

?6. The Right Time (Napoleon Brown - Ozzie Cadena - Lew Herman) 4’29

?7. Memphis Slim Introduction 0’42

?8. Band Introduction (Memphis Slim) 2’10

?9. Rockin’ the House (Peter Chatman) 2’52

10. Hey Baby (James D. Harris) 3’57

11. Call Me When You Need Me (James D. Harris) 3’14

12. Jake’s Blues (James D. Harris) 2’11

13. Talking About the Blues (Willie Dixon) 2’15

14. Nervous (Willie Dixon) 3’53

15. I Just Want to Make Love to You (Willie Dixon) 4’50

16. Baby Please Don’t Go (Joe Lee Williams) 2’14

17. Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie (Clarence Smith) 4’09

First Concert (6:00 PM)

Recorded by: Europe N°1 Technical Staff

Recording date:

October 20, 1962, 6:00 PM

Recording place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by: Daniel Filipacchi, Horst Lippmann , Fritz Rau & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Track 1: Memphis Slim

Tracks 2 to 6: John Lee Hooker, vocals & guitar

Track 7: John Lee Hooker

Track 8: Memphis Slim

Track 9: Memphis Slim, vocals & piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Tracks 10 to 12: Shakey Jake, vocals (10, 11) & harmonica; Memphis Slim, piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 13: Willie Dixon

Tracks 14 & 15: Willie Dixon, vocals & bass; Memphis Slim, piano; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 16 & 17: Memphis Slim, vocals & piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Tracks 2 & 3 with slight distortion

-CD2-

?1. Hugues Panassié, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee Introduction (Memphis Slim) 1’39

?2. I’m a Stranger Here (Sonny Terry / Brownie McGhee) 4’42

?3. Talkin’ Harmonica Blues (Sonny Terry) 3’23

?4. Born and Livin’ With the Blues (Brownie McGhee / Ruth McGhee) 4’31

?5. Baby, I Got My Eye On You (Sonny Terry) 3’29

?6. John Henry (Traditional) 7’07

?7. Woman You Must Be Crazy (Aaron Thibeaux Walker) 5’36

?8. My Old Time Used to Be (Aaron Thibeaux Walker) 4’26

?9. Call it Stormy Monday (Aaron Thibeaux Walker) 4’09

10. You Don’t Love Me (Aaron Thibeaux Walker) 6’18

11. T-Bone Talks to the Booers (Aaron Thibeaux Walker) 1’47

12. Money Honey (Jesse Stone) 2’40

13. Baby Won’t You Please Come Home (Clarence Williams / Charles Warfield) 3’06

14. Kansas City (Jerry Leiber / Mike Stoller) 2’23

15. Saint Louis Blues (W.C. Handy) 2’34

16. Million Dollar Secret (Helen Humes) 3’50

17. Bye Bye Baby (Finale) (Peter Chatman) 10’19

First Concert (6:00 PM)

Recorded by: Europe N°1 Technical Staff

Recording date

October 20, 1962, 6:00 PM

Recording place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by: Daniel Filipacchi, Horst Lippmann, Fritz Rau & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Track 1: Memphis Slim

Tracks 2 to 6: Sonny Terry, vocals on 2, 3, 5, 6 & harmonica; Brownie McGhee, vocals on 2,4,6 & guitar

Tracks 7 to 10: T-Bone Walker, vocals & guitar; Davor Kajfes, piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 11: T-Bone Walker

Tracks 12 to 16: Helen Humes, vocals; T-Bone Walker, guitar; Davor Kajfes, piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 17: Helen Humes, vocals; Memphis Slim, vocals & piano; Shakey Jake, harmonica; John Lee Hooker, vocals; Sonny Terry, harmonica; Brownie McGhee, vocals & guitar; T-Bone Walker, guitar; Willie Dixon, vocals & bass; Jump Jackson,drums

-CD3-

?1. John Lee Hooker Introduction (Memphis Slim) 0’55

?2. Everyday (John Lee Hooker) 6’50

?3. Let’s Make it Baby (John Lee Hooker) 4’11

?4. The Right Time (Napoleon Brown - Ozzie Cadena - Lew Herman) 5’34

?5. It’s My Own Fault (John Lee Hooker) 7’20

?6. Money (Janie Bradford / Berry Gordy Jr) 4’01

?7. Band Introduction (Memphis Slim) 2’51

?8. Rockin’ the House (Peter Chatman) 2’51

?9. Moanin’ (Bobby Timmons) 3’40

10. Money Honey (Jesse Stone) 2’43

11. Baby Won’t You Please Come Home (Charles Warfield - Clarence Williams) 3’34

12. Kansas City (Jerry Leiber / Mike Stoller) 2’35

13. Married Man Blues (Helen Humes) 4’39

14. Bye Bye Baby (Finale) (Peter Chatman) 10’33

Second Concert (12:00 AM)

Recorded by: Europe N°1 Technical Staff

Recording date

October 20, 1962, 12:00 AM

Recording place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by: Daniel Filipacchi, Horst Lippmann, Fritz Rau & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Track 1: Memphis Slim

Tracks 2 to 6: John Lee Hooker, vocals & guitar

Track 7: Memphis Slim

Track 8: Memphis Slim, vocals & piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 9: T-Bone Walker, guitar; Davor Kajfes, piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Tracks 10 to 13: Helen Humes, vocals; T-Bone Walker, guitar; Davor Kajfes, piano; Willie Dixon, bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Track 14: Helen Humes, vocals; Shakey Jake, vocals & harmonica; Memphis Slim, vocals & piano; John Lee Hooker, vocals; Sonny Terry, vocals & harmonica; Brownie McGhee, vocals & guitar; T-Bone Walker, guitar; Willie Dixon, vocals & bass; Jump Jackson, drums

Dedicated to Claude Boquet, Bill Dubois , Jean Claude, Philippe Moch and the gang

Photos: © Gilles Pétard’s collection

BYE BYE BABY

(Chorus)

1st concert

1. Intro instr.

2. H. Humes (vo)

3. S. Terry (ha)

4. Shakey Jake (ha)

5. J. Lee Hooker (vo)

6. — / — (vo)

7. B. Mc Ghee (vo)

8. W. Dixon (vo)

9. T-B. Walker (g)

10. — / — (g)

11. ensemble vo

12. — / —

13. — / —

2nd concert

1. Intro instr

2. H. Humes (vo)

3. S. Terry (ha)

4. Shakey Jake (ha)

5. — / — (vo)

6. — / — (vo)

7. — / — (ha)

8. J. Lee Hooker (vo)

9. — / — (vo)

10. B. Mc Ghee (g)

11. — / — (g)

12. — / — (vo)

13. Memphis Slim (p)

14. W. Dixon (vo)

15. T-B. Walker (g)

16. — / — (g)

17. ensemble vo

18. — / —

19. — / —

La collection Live in Paris :

Collection créée par Gilles Pétard pour Body & Soul et licenciée à Frémeaux & Associés

Direction artistique et discographie : Michel Brillié, Gilles Pétard

Coordination : Augustin Bondoux

Conception : Patrick Frémeaux, Claude Colombini

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés

Remerciements à Jean Buzelin

L’American Folk Blues Festival est une légendaire tournée qui pendant 20 ans, s’est proposée de diffuser le blues authentique en Europe. On retrouve ici à l’Olympia en octobre 1962 les premiers concerts parisiens de John Lee Hooker, Willie Dixon, T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry et Brownie McGhee. Un concert à guichets fermés qui annonce la vague folk et blues revival en Europe et notamment en Angleterre du milieu des années 1960. Frémeaux & Associés et Body & Soul sont fiers de mettre à disposition du public en première mondiale, un document jamais édité et intégral sur 3CD avec présentations, commentaires et réactions du public.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

For twenty years The American Folk Blues Festival was a legendary tour that undertook to spread authentic blues throughout Europe. In October 1962 the tour reached the Olympia in Paris, where the audience could hear the first French concerts by John Lee Hooker, Willie Dixon, T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. The concert sold out. It announced the Folk & Blues Revival wave that went on to sweep Europe & especially Britain in the mid-Sixties. Frémeaux & Associés, together with Body & Soul, are proud to make available to the public this never-released, complete 3CD set that also contains introductions, comments and the enthusiastic reactions of the audience.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

La collection «?Live in Paris?», dirigée par Michel Brillié, permet de retrouver des enregistrements inédits (concerts, sessions privées ou radiophoniques), des grandes vedettes du jazz, du rock & roll et de la chanson du XXe siècle. Ces prises de son live et la relation avec le public apportent un supplément d’âme et une sensibilité en contrepoint à la rigueur appliquée lors des enregistrements studio. Une importance singulière a été apportée à la restauration sonore des bandes pour convenir aux standards CD tout en conservant la couleur d’époque.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTARD

AMERICAN FOLK BLUES FESTIVAL 1962

CD1: MEMPHIS SLIM: 1. Festival Introduction 1’08 - JOHN LEE HOOKER: 2. I’m in the Mood 4’10 • 3. Let’s Make it Baby 4’36 • 4. I Don’t Want to Lose You 5’01 • 5. Money 3’22 • 6. The Right Time 4’29 • 7. Memphis Slim Introduction 0’42 - MEMPHIS SLIM: 8. Band Introduction 2’10 • 9. Rockin’ the House 2’52. SHAKEY JAKE: 10. Hey Baby 3’57 • 11. Call Me When You Need Me 3’14 • 12 Jake’s Blues 2’11 - WILLIE DIXON: 13. Talking About the Blues 2’15 • 14. Nervous 3’53 • 15. I Just Want to Make Love to You 4’50 - MEMPHIS SLIM: 16. Baby Please Don’t Go 2’14 • 17. Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie 4’09.

CD2: MEMPHIS SLIM: 1. Hugues Panassié, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee Introduction 1’39 - SONNY TERRY & BROWNIE MCGHEE: 2. I’m a Stranger Here 4’42 • 3. Talkin’ Harmonica Blues 3’23 • 4. Born and Livin’ With the Blues 4’31 • 5. Baby, I Got My Eye On You 3’29 • 6. John Henry 7’07 - T-BONE WALKER: 7. Woman You Must Be Crazy 5’36 • 8. My Old Time Used to Be 4’26 • 9. Call it Stormy Monday 4’09 • 10. You Don’t Love Me 6’18 • 11. T-Bone Talks to the Booers 1’47 - HELEN HUMES: 12. Money Honey 2’40 • 13. Baby Won’t You Please Come Home 3’06 • 14. Kansas City 2’23 • 15. Saint Louis Blues 2’34 • 16. Million Dollar Secret 3’50 - ENSEMBLE: 17. Bye Bye Baby (Finale) 10’19.

CD3: MEMPHIS SLIM: 1. John Lee Hooker Introduction 0’55 - JOHN LEE HOOKER: 2. Everyday 6’50 • 3. Let’s Make it Baby 4’11 • 4. The Right Time 5’34 • 5. It’s My Own Fault 7’20 • 6. Money 4’01 - MEMPHIS SLIM: 7. Band Introduction 2’51 • 8. Rockin’ the House 2’51 - T-BONE WALKER: 9. Moanin’ 3’40 - HELEN HUMES: 10. Money Honey 2’43 • 11. Baby Won’t You Please Come Home 3’34 • 12. Kansas City 2’35 • 13. Married Man Blues 4’39 – ENSEMBLE: 14. Bye Bye Baby (Finale) 10’33.