- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

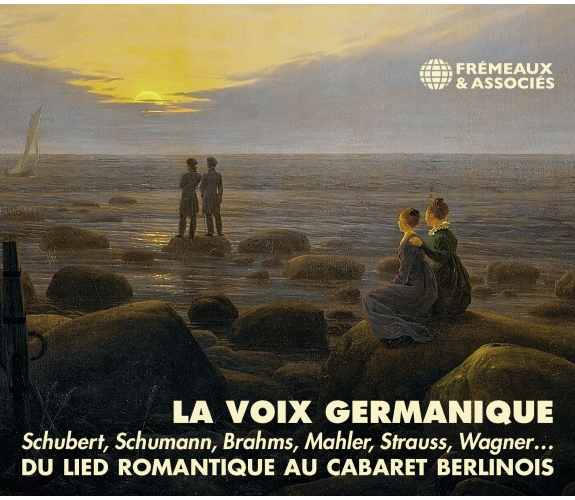

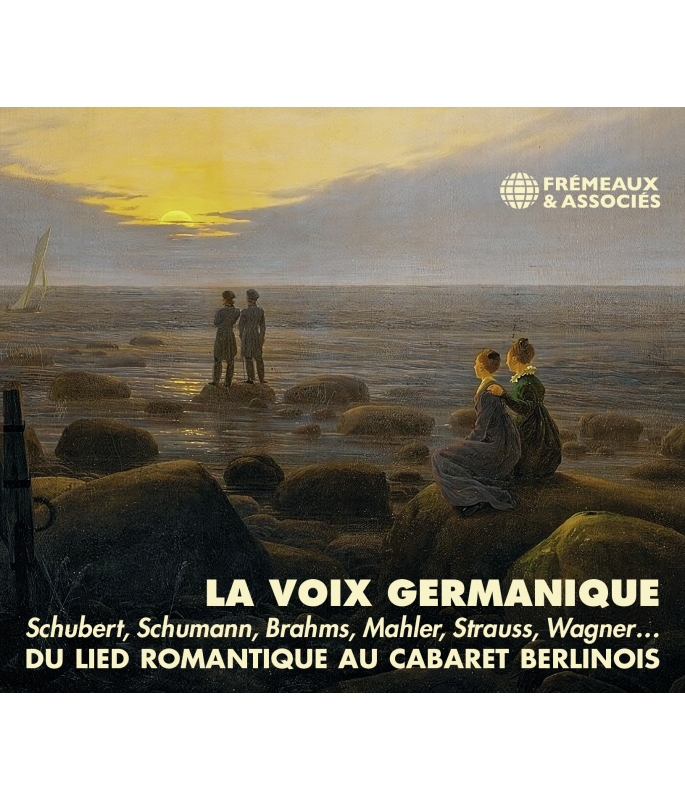

du lied romantique au cabaret berlinois

(Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Mahler, Strauss, Wagner...)

Ref.: FA5890

EAN : 3561302589022

Artistic Direction : Philippe Lesage & Téca Calazans

Label : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 29 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

du lied romantique au cabaret berlinois

(Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Mahler, Strauss, Wagner...)

With these Lieder, those miniatures with sensual melodies where the song condenses a destiny, this anthology provides a path through over a century of Germany’s culture. The overview here illustrates the Romantic Lied of the 19th century, as well as its extensions a hundred years later, with orchestral songs and hybrid readings nuanced by jazz and the spirit of Berlin’s cabarets.

Philippe LESAGE

CD1 - SCHUBERT : STÄNDCHEN (DIETER FISHER-DIESKAU) • ABSCHIED (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • GUTE NACHT (HANS HOTTER) • DIE POST (H. HOTTER) • DER LEIERMANN (H. HOTTER) • ERLKÖNIG (GÉRARD SOUZAY) • GANYMED (ELISABETH SCHWARZKOPF) • IM FRÜHLING (E. SCHWARZKOPF) • AN DIE MUSIK (E. SCHWARZKOPF) • GRETCHEN AM SPINNRADE (E. SCHWARZKOPF) • NACHTVIOLEN (E. SCHWATZKOPF) • DIE FLORELLE (G. SOUZAY) • DER DOPPLEGÄNGER (G. SOUZAY). SCHUMANN : L’AURORE LA ROSE LE LYS (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • INVOCATION (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) LES NOCES (D. FISHER DIESKAU) • CHANSON DE L’AIMÉ (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • HISTOIRE ANCIENNE (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • PLEURS EN RÊVE (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • FANTASMAGORIE (D. FISHER-DIESKAU). BRAHMS : MEERFAHRT (D. FISHER-DIESKAU) • DER TOD DAS IST DIE KÜHLE NACHT (D.FISHER-DIESKAU). WOLF : GESANG WEYLAS (CHRISTA LUDWIG) • AUF EINER WANDERUNG (C. LUDWING) • MIGNON (IRMGARD SEEFRIED).

CD2 - MAHLER : WENN MEIN SCHATZ HOCHZEIT MACHT (CHRISTA LUDWIG) • GING HEUT’MORGEN ÜBERS FELD (C. LUDWIG). RICHARD STRAUSS : IM ABENDROT (E. SCHWARZKOPF) • SEPTEMBER (E. SCHWARZKOPF). WAGNER : ISOLDES LIEBESTOD (C. LUDWIG). BERG : SEELE WIE BIST DU SCHÖNER (BETHANY BEARDSLEE) • SAHST DU MACH DEM GEWITTERREGEN (B. BEARDSLEE) • ÜBER DIE GRENZEN DES ALL (B. BEARDSLEE) • NICHTS IST GEKOMMEN (B. BEARDSLEE) • HIER IST FRIEDE (B. BEARDSLEE) • LULU’S SONG (HELGA PILARCZYK. WEILL : COMPLAINTE DE MACKIE (WOLFGANG NEUSS) • DUO DE LA JALOUSIE (LOTTE LENYA & WILLY TRENK-TREBITSCH) • BARBARA SONG (L. LENYA) • SURABAYA JONNY (L. LENYA) • BILBAO SONG (L. LENYA) • ALABAMA SONG (L. LENYA) • DENN WIE MAN SICH BETTET (L. LENYA). HOLLAENDER : FALLING IN LOVE AGAIN (MARLENE DIETRICH) • WENN DIE BESTE FREUDIN (M. DIETRICH & MARGO LION) • JONNY (M. DIETRICH). SCHULTZE : LILI MARLENE (M. DIETRICH). RUDOLF NELSON : DAS NACHTGEPENST (KURT GERRON).

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : PHILIPPE LESAGE ET TECA CALAZANS

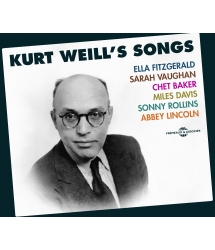

ELLA FITZGERALD • SARAH VAUGHAN • CHET BAKER • MILES...

MUSIQUES FOLKLORIQUES ET RÉGIONALES

60 YEARS OF SCOTTISH GAELIC

Noel Rosa - Dorival Caymmi - Vinicius De Moraes

Traditional Music & Songs

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Franz Schubert - Ständchen, du recueil Schwannengesang, D. 957 (Le Chant du Cygne)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauLudwig Rellstab00:03:391951

-

2Franz Schubert - Abschied, du recueil Schwannengesang, D. 957 (Le Chant du Cygne)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauLudwig Rellstab00:03:041955

-

3Franz Schubert - Gute Nacht, du recueil Die Winterreise D 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)Hans HotterWilhelm Müller00:06:041954

-

4Franz Schubert - Die Post, du recueil Die Winterreise, D. 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)Hans HotterWilhelm Müller00:02:131954

-

5Franz Schubert - Der Leiermann, du recueil Die Winterreise, D. 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)Hans HotterWilhelm Müller00:04:181954

-

6Franz Schubert - ErlKönig, D. 328 (Le Roi des Aulnes)Gérard SouzayJohann Wolfgang von Goethe00:03:511961

-

7Franz Schubert - Ganymed, D. 544 opus 19 n°3Elisabeth SchwarzkopfJohann Wolfgang von Goethe00:04:471952

-

8Franz Schubert - Im Frühling, D. 882Elisabeth SchwarzkopfErnst Conrad Friedrich Schulze00:04:251952

-

9Franz Schubert - An Die Music, D. 547 op 88 n°4Elisabeth SchwarzkopfFranz Adolf Friedrich Schober00:02:381952

-

10Franz Schubert - Gretchen Am Spinnrade, D. 118 op 2Elisabeth SchwarzkopfJohann Wolfgang von Goethe00:03:251952

-

11Franz Schubert - Nachtviolen, D. 752Elisabeth SchwarzkopfJohann Baptist Mayrhofer00:02:471952

-

12Franz Schubert - Die Florelle D. 550Gérard SouzayChristian Friedrich Daniel Schubart00:01:591961

-

13Franz Schubert - Der Dopplegänger, du recueil Schwanengesang D.957 (Le Chant du cygne)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:04:411961

-

14Robert Schumann - Die Rose, Die Lilie, Die Taube, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:00:311960

-

15Robert Schumann - Und Wüssten’s Die Blumen, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:01:141960

-

16Robert Schumann - Das Ist Ein Flötten Und Geign, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:01:211960

-

17Robert Schumann - Hoï Ich Das Liedchen Klingen, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:01:541960

-

18Robert Schumann - Ein Jüngling Liebt Ein Mädchen, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:01:051960

-

19Robert Schumann - Ich Hab’ Im Traume Geweinet, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:02:481960

-

20Robert Schumann - Aus Alten Marchen, du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:02:441960

-

21Johannes Brahms - Meerfahrt op 96 n°4Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:03:001960

-

22Johannes Brahms - Der Tod, Das Ist Die Kühle Nacht op 96 n° 1Dietrich Fischer-DieskauHenri Heine00:03:221960

-

23Hugo Wolf - Gesang Weylas, du recueil Mörike-Lieder IHW 22Christa LudwigEduard Mörike00:01:391957

-

24Hugo Wolf - Auf Einer Wanderung, du recueil Mörike-Lieder IHW 23Christa LudwigEduard Mörike00:03:261957

-

25Hugo Wolf - Mignon, du recueil Goethe-Lieder IHW 10Imgard SeefriedJohann Wolfgang von Goethe00:03:071961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Gustav Mahler - Wenn Mein Schatz Hochzeit Macht, du recueil Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gessellen IGM 5 (chants d’un compagnon errant)Christa LudwigGustav Mahler00:04:211958

-

2Gustav Mahler - Ging Heut’Morgen Übers Feld, du recueil Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gessellen IGM 5 (chants d’un compagnon errant)Christa LudwigGustav Mahler00:04:461958

-

3Richard Strauss - Im Abendrot, du recueil 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Quatre dernier Lieder)Elisabeth SchwarzkopfJoseph von Eichendorff00:07:171953

-

4Richard Strauss - September, du recueil 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Quatre dernier Lieder)Elisabeth SchwarzkopfHerman Hesse00:04:081953

-

5Richard Wagner - Isoldes Liebestod, Acte 3 de Tristan & IsoldeChrista LudwigRichard Wagner00:06:491962

-

6Alban Berg - Seele, Wie Bist Du Schöner, du recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskar tentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4Betty BeardsleePeter Altenberg00:03:011959

-

7Alban Berg - Sahst Du Nach Dem Gewitterregen Den Wald, du recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskar tentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4Betty BeardsleePeter Altenberg00:01:101959

-

8Alban Berg - Über Die Grenzen Des All, du recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskar tentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4Betty BeardsleePeter Altenberg00:01:361959

-

9Alban Berg - Nichts Is Gekommen, du recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskar tentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4Betty BeardsleePeter Altenberg00:01:311959

-

10Alban Berg - Hier Ist Friede, du recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskar tentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4Betty BeardsleePeter Altenberg00:03:381959

-

11Alban Berg - Lulu’s Song, de Lulu Suite IAB 4Helga PilarczykAlban Berg00:02:141961

-

12Kurt Weill - La Complainte de Mackie, extrait de l'Opéra de quat'sousWolfgang NeussBertold Brecht00:03:041958

-

13Kurt Weill - Duo de la Jalousie / EiffersuchtsduettLotte Lenya, Willy Trenk-TrebistchBertold Brecht00:01:231930

-

14Kurt Weill - BarbarasongLotte LenyaBertold Brecht00:02:031930

-

15Kurt Weill - Surabaya JonnyLotte LenyaBertold Brecht00:03:001929

-

16Kurt Weill - Bilbao SongLotte LenyaBertold Brecht00:03:041929

-

17Kurt Weill - Alabama Song, extrait de Aufstieg und fall der Stadt MahagonnyLotte LenyaBertold Brecht00:03:001930

-

18Kurt Weill - Denn Wie Man Sich Bettet, So Lieght Man, extrait de Aufstieg und fall der Stadt MahagonnyLotte LenyaBertold Brecht00:02:541930

-

19Friedrich Hollaender - Falling In Love AgainMarlene DietrichReg Connelly00:03:101930

-

20Friedrich Hollaender - Wenn Die Beste FreundinMarlene DietrichFriedrich Hollaender00:03:101928

-

21Friedrich Hollaender - JonnyMarlene DietrichFriedrich Hollaender00:03:091931

-

22Norbert Schultze - Lili Marlene, extrait de Der Blaue Engel (L’Ange Bleu)Marlene DietrichHans Leip00:03:241945

-

23Rudolf Nelson - Das NachtgespenstKurt GerronFriedrich Hollaender00:03:381930

The Germanic Voice: From Romantic Lied to Berlin Cabaret

The Poetic Dimension of German Song

This anthology offers a journey through more than a century of Germanic culture. It focuses on the Romantic Lied of the 19th century and its extensions at the turn of the 20th century, with orchestral Lieder and interpretations of Lied infused with jazz, musical theatre, and cabaret. The composers featured in this anthology are either German (Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Richard Strauss, Kurt Weill, Friedrich Hollaender) or Austrian (Franz Schubert, Hugo Wolf, Gustav Mahler, Alban Berg). As refined literati, they skillfully set to music the poetic texts of major writers such as Goethe, Heine, and Brecht, while also favoring minor authors for the musicality of their verses.

Why and How to Marry Poetry and Music?

This is a crucial question for understanding the approach taken by composers like Schubert, Schumann, Wolf, or Brahms when they chose to set Romantic-era poems to music. By taking a detour, which might seem incongruous, we admit, to the dialogue between Léo Ferré and Aragon on the subject of poetry set to music, we believe we can largely clarify the resolution of this question. Léo Ferré's direct words get straight to the point: "Poetry is self-sufficient, and so is music. So why marry the two?" He then offers a partial answer: "I don't really believe in the music of verses but in a certain form conducive to the meeting of verses and melody. I don't believe in collaboration but in a double vision: that of the poet who writes, and that of the musician who then perceives musical images behind the door of words." He is careful to add: "What Aragon unfolds in poetic phrasing needs no support, of course, but the very material of his language is made for the loom of sounds." Doesn't this clarification illuminate Schubert's relationship with Wilhelm Müller's poetry and Schumann's with Heine? And Aragon's own comment ("Poetry doubled by musical magic almost always requires significant textual recomposition from the composer — cutting, creating refrains, changing titles — for greater effectiveness and clarity") reinforces historical musicological teachings on the conception of Lieder, which show that the musical setting subtly freed itself from the strophic form of the poems.

How to Define the Romantic Lied?

"The Lied phenomenon is important," emphasized Laurence Equilbey during a broadcast on France Culture; she clarified her thought by pointing out that it was a music without insolence, rooted in the earth and in the people, stemming from the German Romantic movement. Although not exactly contemporary with literary Romanticism, the Romantic Lied necessarily takes flight from its ingredients; the musical setting of Goethe's poem "Erlkönig" (The Elf King) attests to this. It is the emergence of a popular art (in which Goethe and Brentano already showed interest), certainly, but one propagated by the bourgeoisie and primarily intended for them. One thinks of works written for friendly gatherings, like the famous Schubertiades, where one sings purely for pleasure. In the Romantic Lied, mythology and aristocratic figures are set aside. It sings of the lives of simple and humble people, like that of the miller or the wanderer, the vagabond, a central character in Schubert's Winterreise. 20th-century composers like Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, and Alban Berg will always refer to the Lied, sometimes in its classic voice-and-piano form; but they will innovate by expanding the expression towards the orchestral Lied. With Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, and Paul Dessau, the Lied will distinguish itself by its militant, political, and social commitment and will adorn itself with the trappings of cabaret and jazz.

One of the reasons for its success, at the time of its creation and still today, lies in a form of simplicity born from the popular character of the Lied. This simplicity can be summarized as follows: the Lied is the exposition of a musical and poetic idea enclosed in a brief form that, musically, does not require development or counterpoint, but instead calls for a form of dialogue between the voice that presents the poetic text and the piano accompaniment, which must rise to the level of the emotion. The Lied is essentially a miniature that condenses a destiny into a few words, exploring existential abysses. Its favorite themes, rarely explored by classical popular song which favors romantic desires and laments, revolve around wandering, consoling death, and affects related to nature, to which must be added the essential motif of all poetry regardless of genre or country: the love of the inaccessible woman. But let us emphasize that beyond its recurring themes, it is indeed music that always takes precedence in the dialogue with poetry.

The Romantic Lied gained prominence with Schubert. Musicologist Sylvain Fort, in a remarkable study for Diapason magazine, demonstrates that with him, there was a total transfiguration of the Volkslied (folk song with a strong folkloric connotation). A triple revolution occurred: a poetic revolution, a revolution of the imagination, and one of interpretation. And the Lied would henceforth symbolize the romantic relationship with the world. To highlight the poetic revolution, one cannot fail to note Schubert's friendly ties with the poets Mayrhofer and Schobert, and Schumann's and Wolf's literary taste of great certainty.

The Combination of Voice and Piano

Roland Barthes, who took singing lessons and detested the bourgeois emphasis of Gérard Souzay's diction, commented in a radio broadcast: "In opera, it is the sexual timbre of the voice that is important; on the contrary, in the Lied, it is the tessitura that matters; therefore, here, no excessive notes, no shouts, no overflows, no physiological prowess. The tessitura is the modest space of sounds that each of us can produce and within whose limits it is possible to fantasize the reassuring unity of the body. In all Romantic music, vocal or instrumental, it is the song of the natural body. It is music that only makes sense if I can sing it within myself with my body." All discographies confirm this: all vocal timbres color the world of the Lied, but extremes of register, which belong more to the world of opera, are avoided. In fact, in the Lied, vocal technique most often results in a fusion of the aria and the recitative.

In Lied literature, the melodies are enchanting and sensual. And the piano is never against the voice. In fact, as musicologist Sylvain Fort so aptly puts it: "the piano constantly modulates, changes key as in a conversation, changes tone, and the vocal line is constantly infused." The ultimate goal is always for the music to have the final say in the dialogue with poetry. Moreover, quite quickly, as musicologist Hélène Cao points out, music freed itself from the strophic subjection of the poem to take charge of the dramatic and psychological evolution; and forms diversified by modifying the writing of the piano part while the singer repeats the melody. It should be noted that all 19th-century composers were gifted pianists, and this favored the diversification of writing, which itself went hand in hand with that of harmonic language.

Franz Schubert (1799-1828)

If there is one book that makes you want to immerse yourself in Schubert's work, it is certainly the biography Schubert and the Infinite: On the Horizon, the Desert. "Of us, the jealous and the fearful, of us, Schubert is the brother," comments his biographer Jacques Drillon, who emphasizes that Schubert "takes us by the hand, by his humility." He praises the composer's purity and refinement of thought and rightly notes that Lieder organized into cycles (often by publishers) do not equal the sum of their parts. Thus, Schwanengesang (Swan Song) is superior to Winterreise, although it is not an authentic cycle.

Author of 625 Lieder – he wrote several a day – Schubert is the one who established the Lied's preeminence. It goes without saying, therefore, that his Lieder open the first disc of the anthology and that his work is presented first in this booklet. Contemporary of Goethe (who never recognized him) and Beethoven (whom he admired without ever meeting), he achieved the total transfiguration of a musical and literary genre by instilling the romantic relationship with the world. Schubert sought the power of expression in texts whose imagination, inner power, and poetic suggestion had to be revealed by the music. In fact, he only chose texts that he could make sound and resonate, even those by Goethe or Schiller. He felt the same obsessions as Wilhelm Müller (1794-1821), who was a librarian considered a minor poet but whose writing called for music, namely modest love, solitude, wandering, anxiety, and the feeling of collapse. In Schubert, still according to Jacques Drillon, the Lied is an immediate given of consciousness: clarity of contours, transparency of expression, certainty of melodic instinct, restraint and modesty in the music, great economy of means despite the complexity of the accompaniment with its harmonic daring.

The perfection of his Lieder also lies in the fact that he gave the piano the opportunity to become another voice; this was the key to unostentatiously opening the hidden world of the literary text. This is the case with Winterreise, composed in Vienna in 1827 based on poems by Müller (poet of Die Schöne Müllerin), which would be performed on December 12th after his death for numbers 13 to 24 and on February 14th, 1828 for the first 12. It is a succession of vignettes, psychological states, and the depiction of a condemnation to endless wandering. The last Lied, "Der Leiermann," offers an open ending on the threshold of madness. And it is unforgettable.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Schumann's Lieder, like Schubert's, are imbued with torment, but they are less spontaneous. Nevertheless, they possess a captivating power, as composer and musicologist André Boucourechliev (Schumann, Solfèges collection, Édition du Seuil) points out. For the 248 Lieder, a hundred of which were composed in 1849, the year of existential doubt, Schumann drew from all the poets of his time, from the most illustrious to the most obscure. He made Rückert the translator of his love for Clara, borrowed texts by Mörike and Eichendorff which called for melody; but it was in Heine's poetry that he found the ambivalent and contradictory tendencies of his personality. In 1840, Dichterliebe (The Poet's Love) (16 melodies of astonishing diversity in inspiration, writing, and atmosphere) was a total accomplishment. To Schumann's great dismay, Henri Heine never recognized him. Close to Robert Schumann and especially Clara, Brahms also cultivated the Lied throughout his life and meticulously supervised the order of the 33 collections (190 Lieder chosen to be presented to the public after a long maturation) published between 1853 and 1896. Like all Romantics, he sang of the peace found in nature, as well as the nostalgia of unrequited love and the solitude of the human condition. The two Lieder present in this anthology are among the most beautiful he composed. "Meerfahrt" is a kind of barcarolle, and "Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht" (Death, that is the cool night) is considered one of the most moving Lieder in the entire history of song; it develops the idea of consoling death, dear to Brahms.

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903)

A Viennese of Slovenian origin, Hugo Wolf, who detested Brahms ("the pedantic Northerner"), established himself with a subtle and innovative art as the last of the great masters of the Lied with piano. He composed 345 Lieder based on poems by Heine, Eichendorff, and Mörike (a theologian with erotic fantasies who was not without irony), three poets who were not of his generation. In Spanisches Liederbuch (10 sacred and 34 secular Lieder), he set to music Spanish poets including Cervantes, Lope de Vega, and Gil Vicente, and in 1897, he composed the Michelangelo-Lieder. It is true that Wolf, like Schumann, was a man of letters. His conception of vocal progression gave birth to a new melodic form, and his pieces are conceived as miniature symphonic poems with rapid modulations, dissonances, and free structures; to the point that Mahler, his contemporary, found his Lieder shapeless.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Richard Strauss (1861-1949)

With Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, we approach the shores of Lieder with orchestra, where Wagner's influence is evident. While the Rückert-Lieder cycle is perceived as Mahler's most seductive and lyrical, one should not overlook his other great cycles: Des Knaben Wunderhorn; Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (two are present in this anthology); and Kindertotenlieder. Like Mahler, Richard Strauss was a genius of orchestration. The Four Last Songs is a work performed after the composer's death on May 22, 1950, in London by Kirsten Flagstad and the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Furtwängler, but Elisabeth Schwarzkopf delivered the most acclaimed version. There is no thematic link between the four Lieder (three are by Herman Hesse – who, incidentally, hated Richard Strauss – and "Im Abendrot" by Eichendorff; our anthology includes only two), only an autumnal color favoring transcendence. This hymn to the glory of the voice – Richard Strauss's wife was a singer – concludes with a final verse that resonates like the testament of an octogenarian composer ("how weary we are of wandering! Could this already be death?").

Alban Berg (1885-1935)

Alban Berg, a prominent representative of the Second Viennese School, in composing his Lieder, followed in the footsteps of Wagner, Schumann, Richard Strauss, Mahler, and his revered teacher Schoenberg. The latter had composed an immoderate orchestral score with post-Wagnerian colors in 1900: the Gurre-Lieder. Alban Berg, while continuing the tradition of the Lied with orchestra, aimed for conciseness and gave ample space to silence in Fünf Orchesterlieder von Peter Altenberg opus 4. These are five Lieder written in 1912 based on texts from postcards by Peter Altenberg (1859-1919), a writer said to have had the physical features and lifestyle of Verlaine. On texts that are at least elliptical, these are five portraits of passionate, solitary, and loving women. With a central twelve-tone chord that disintegrates, the third Lied is by far the most dramatic ("suddenly everything is over"); the fourth Lied is the most complex, and the fifth is a dodecaphonic passacaglia; the second, very erotic, is a pure bel canto piece.

Kurt Weill (1900-1950); Hanns Eisler (1898-1961)

A gradual shift towards other spheres was initiated by Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, and Paul Dessau (1894-1976), three composers whose social and political ideas were so strongly leftist that they would become companions of the communists. Their works would be considered decadent by the Nazis. They had trained at conservatories and possessed masterful technique (Eisler was Schoenberg's student, among others), but they would leave the ruts of post-Romanticism and dodecaphony to associate with the poet and dramatist Bertolt Brecht. Their aesthetic: to create a musical theater that spoke to everyone without neglecting audacious writing. The names of Brecht and Weill will forever remain inextricably linked to the effervescence of the Berlin years in the history of arts, even though their common works only ran from 1927 to 1933. It was Lewis Ruth's orchestra, under the baton of Theo Mackeben, that performed on January 31, 1928, for the premiere of The Threepenny Opera; Lotte Lenya was then Jenny, and it was an immense immediate success. Lotte Lenya, who had an agitated romantic life with Kurt Weill, would record several albums under her own name in 1958 and 1960, but we chose to highlight the sound illustrations from 1928-1933 where her unique voice is at its peak. A few words about Hanns Eisler who, although born in Leipzig, is considered Austrian. He was Schoenberg's student before moving to Berlin and collaborating with Brecht from 1929; they would continue to work together during their exile in the USA and until the playwright's death in 1956 in the GDR. The singer Matthias Goerne has given an excellent version of the Hollywood Liederbuch cycle, composed in America in 1942, which perfectly fits into our study of the Lied's continued presence.

Friedrich Hollaender (1896-1976)

Although born in England, he was German and continued his studies in Berlin. After composing for the theater, working for director Max Reinhardt, he entered the world of cinema, which he never left, whether in Germany or the USA (where he went into exile in 1933, foreshadowing the arrival of other Jewish composers such as Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler). He composed the music for over a hundred films, including Josef Von Sternberg's The Blue Angel in 1929 (filmed in two versions, German and English), Ernst Lubitsch's Heaven Can Wait, and Billy Wilder's Sabrina. For Marlene Dietrich, he wrote both lyrics and music, including the famous "Falling In Love Again." He can be seen alongside the singer playing the accompanying pianist in the film A Foreign Affair. Is it still possible to count him among Lied composers? One can answer positively if one considers that he fits well within the popular song tradition, exploring existential abysses and condensing a destiny into a few words. And isn't his muse Marlene Dietrich the symbol of the liberated German woman, on par with Lotte Lenya?

Teca CALAZANS and Philippe LESAGE

All our thanks to musicologist Hélène CAO and Jean Buzelin, who is so knowledgeable about Kurt Weill's Berlin years.

Bibliography

Anthologie du lied, Hélène Cao and Hélène Boisson (Buchet Chastel, Paris)

© 2025 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Discography

THE GERMANIC VOICE - FROM ROMANTIC LIED TO BERLIN CABARET

CD1

-

Ständchen (Schubert – Ludwig Rellstab) From Schwanengesang D 957 (Swan Song) D 957 Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baritone) Gerald Moore (piano) October 7, 1951 78 rpm HMV DB 21349

-

Abschied (Schubert – Rellstab) From Schwanengesang D 957 (Swan Song) D 957 Dieter Fisher – Dieskau (baritone) Gerald Moore (piano) A Schubert Lieder Recital / 1955 LP HMV 1295

-

Gute Nacht (Schubert – Wilhelm Müller) From Die Winterreise D 911 (Winter Journey) Hans Hotter (baritone) Gerald Moore (piano) May 1954 Emi Angel Records 3521

-

Die Post (Schubert – Müller) From Die Winterreise D 911 (Winter Journey) Same as 3

-

Der Leiermann (Schubert – Müller) From Die Winterreise D 911 (Winter Journey) Same as 3

-

Erlkönig (Schubert – Goethe) D328 (The Elf King) Gérard Souzay (baritone) Dalton Baldwin (piano) June 1961 Philips 835 097 AY

-

Ganymed D.544 opus 19 N°3 (Schubert – Goethe) Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano) Edwin Fischer (piano) October 1952 Columbia 33 CX 1040

-

Im Frühling D.882 (Schubert – Schulze) Same as 7

-

An Die Musik D.547 op 88 N°4 (Schubert – Schober) Same as 7

-

Gretchen Am Spinnrade D.118 op 2 (Schubert – Goethe) Same as 7

-

Nachtviolen D752 (Schubert – Mayrhofer) Same as 7

-

Die Forelle D 550 (Schubert – Schubart) Gérard Souzay (baritone) Dalton Baldwin (piano) June 1961 Philips 835 097 AY

-

Der Dopplegänger (Schubert – Heine) From Schwanengesang D.957 (Swan Song) Same as 12

-

Die Rose, Die Lilie, Die Taube (Schumann – Henri Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baritone) Jorg Demus (piano) 1960 DG 18370

-

Und Wüssten’s Die Blumen (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Das Ist Ein Flötten Und Geign (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Hör’ Ich Das Liedchen Klingen (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Ein Jüngling Liebt Ein Mädchen (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Ich Hab’ Im Traume Geweinet (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Aus Alten Märchen (Schumann – Heine) From Dichterliebe op.48 (The Poet's Love) Same as 14

-

Meerfahrt op 96 n°4 (Brahms – Heine) Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baritone) Jorg Demus (piano) 1960 DG 18370

-

Der Tod, Das Ist Die Kühle Nacht op 96 n° 1 (Brahms – Heine) (Death, that is the cool night) Same as 21

-

Gesang Weylas (Hugo Wolf – Mörike) From Mörike-Lieder IHW 22 Christa Ludwig (mezzo-soprano) Gerald Moore (piano) 1957 EMI Columbia 33 CX1552

-

Auf Einer Wanderung (Hugo Wolf – Mörike) From Mörike-Lieder IHW 22 Same as 23

-

Mignon (Wolf – Goethe) From Goethe-Lieder IHW 10 Irmgard Seefried (soprano) Erik Werba (piano) LP Anthologie du lied (2) 1961 DG 18155

CD2

-

Wenn Mein Schatz Hochzeit Macht (Mahler) From Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen IGM 5 (Songs of a Wayfarer) Christa Ludwig (mezzo-soprano) Philharmonia Orchestra, cond. Sir Adrian Boult October 18, 1958 EMI Angel Records S 35776

-

Ging Heut’ Morgen Übers Feld (Mahler) From Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen IGM 5 (Songs of a Wayfarer) Same as 1

-

Im Abendrot (Richard Strauss – Joseph von Eichendorff) From 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Four Last Songs) Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano) Philharmonia Orchestra, cond. Otto Ackermann September 25, 1953 EMI Columbia 33 SC 107I

-

September (Richard Strauss – Herman Hesse) From 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Four Last Songs) Same as 3

-

Isoldes Liebestod (Wagner) Act 3 of Tristan & Isolde Christa Ludwig (mezzo-soprano) Philharmonia Orchestra, cond. Otto Klemperer March 25, 1962 EMI Columbia SAX 2462

-

Seele, Wie Bist Du Schöner (Alban Berg - Peter Altenberg) (Soul, How Much More Beautiful You Are) From Fünf Orchesterlieder nach Ansichtskartentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4 Betty Beardslee (soprano) Columbia Symphony Orchestra, cond. Robert Craft June 5 and 17, 1959 Columbia ML 5428 / MF 61035

-

Sahst Du Nach Dem Gewitterregen Den Wald (Berg - Altenberg) (Did you see, after the thunderstorm rain, the forest) Same as 6

-

Über Die Grenzen Des All (Berg – Altenberg) (Beyond the Boundaries of the Universe) Same as 6

-

Nichts Ist Gekommen (Berg – Altenberg) (Nothing Has Come) Same as 6

-

Hier Ist Friede (Berg – Altenberg) (Here is Peace) Same as 6

-

Lulu’s Song (Berg) From Lulu Suite IAB 4 Helga Pilarczyk (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra, cond. Antal Dorati June 19 to 22, 1961 Mercury SR -90278

-

La Complainte de Mackie / Mackie Messer Moritat (Kurt Weill – Bertolt Brecht) From The Threepenny Opera Wolfgang Neuss (Moritatsinger) / Orchestra of Sender Freies Berlin, cond. Wilhelm Brückner – Ruggeberg 1958 CBS 78279

-

Duo de la Jalousie / Eifersuchtsduett (Weill – Brecht) Lotte Lenya and Willy Trenk-Trebitsch; Lewis Ruth Band, cond. Theo Mackeben 1930 Ultraphon 77752

-

Barbarasong Lotte Lenya, same ensemble as 13

-

Surabaya Jonny (Weill – Brecht) Song from Happy End Lotte Lenya, Theo Mackeben mit seinen Jazz Orchester Berlin 1929 Orchestrola 2311

-

Bilbao Song (Weill – Brecht) Song from Happy End Lotte Lenya, same ensemble as 15

-

Alabama Song (Weill – Brecht) From Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny Lotte Lenya & The Three Admirals; cond. Theo Mackeben & His Jazz Orchestra Berlin, February 24, 1930 Ultraphon A 37

-

Denn Wie Man Sich Bettet, So Liegt Man Same as 17

-

Falling In Love Again (music: Friedrich Hollaender – text: Connelly) From Der Blaue Engel (The Blue Angel) Marlene Dietrich February 6, 1930 HMV B3524

-

Wenn Die Beste Freundin (Hollaender) Marlene Dietrich, Margo Lion, Oscar Karlweiss and piano accompaniment by Mischa Spoliansky June 2, 1928 Electrola EG 892

-

Jonny (Hollaender) Marlene Dietrich; Peter Kreuder Orchestra 1931 Ultraphon A887

-

Lili Marlene (music: Norbert Schultze – text: Hans Leip & Marlene Dietrich) Marlene Dietrich; Charles Magnante Orchestra September 7, 1945 Decca 73031

-

Das Nachtgespenst (Rudolf Nelson; text: Friedrich Hollaender) Kurt Gerron (vocals) Rudolf Nelson (piano) March 1930 Ultraphon Telefunken A388

GERMAN SONG:

FROM ROMANTIC LIEDER TO THE CABARETS OF BERLIN

The poetic dimension of German song

This anthology allows you to discover more than a century of Germany’s culture. It deals with the Romantic Lied of the 19th century, and its consequent evolutions at the turn of the 20th century with orchestral versions of songs and readings that show the influences of jazz, musicals and cabarets. The composers featured here are either German (Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Richard Strauss, Kurt Weill, Friedrich Hollaender) or Austrian (Franz Schubert, Hugo Wolf, Gustav Mahler, Alban Berg). As elegant men of letters, they would be capable of setting poetic texts to music, pieces written by major writers such as Goethe, Heine and Brecht, although they didn’t neglect minor authors known for the musicality of their verse.

How can the Romantic Lied be defined?

In a programme she presented on Radio France Culture, Laurence Equilbey would emphasise that “the Lied phenomenon is important.” She clarified by saying it was music without insolence, anchored in the country and its people, and its origins lay in Germany’s Romantic movement. Even though its form is not exactly contemporary with Romanticism in literature, the Lied necessarily achieved popularity due to its ingredients (as shown by the setting to music of Goethe’s poem Der Erlkönig (“The Era King.”) Of course, it was also the emergence of a popular art-form (one that already interested Goethe and Brentano) but it was propagated by the bourgeoisie at whom it was aimed. It reminds one of the works written for meetings between friends – like the famous Schubertiades held to celebrate Schubert – where people sang only for pleasure.

In the Romantic Lied, mythology and aristocratic figures are excluded; the songs refer to the lives of people who are simple and humble, like the character of the miller or the wanderer, the vagabond, the central figure in Schubert’s Winterreise. XXth century composers like Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg would always make reference to the Lied, sometimes in the classic voice-piano format. But they would innovate by broadening its expression towards the orchestral Lied. With Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler and Paul Dessau, this song-form would stand apart by its militancy, both political and social, in its activism, and it would take on the showy guise of the universe to which jazz and the cabarets belonged.

One reason for its success at the time of its creation (and still today) is due to a form of simplicity that stems from the popular nature of the Lied itself. It is a simplicity that can be resumed as follows: the Lied is the statement of a poetic and musical idea clasped inside a brief form which, musically speaking, demands neither development nor counterpoint, but calls for a form of dialogue between the voice that states the poetic text and the accompaniment of the piano, which has to come forward to be in tune with the sentiment.

The Lied is in essence a miniature that in only a few words condenses a destiny over an exploration of existential abysses. Its preferred themes (which are little-explored by classic songs that favour the desire and grievances of love) deal with aimlessness, consolation in death, and the consequences of a bond with nature, to which can be added the essential motif of all poetry, whatever its genre or country: the love for a woman who is unattainable. But we can emphasise that, beyond its recurrent themes, it is indeed the music that always has pre-eminence in the dialogue with poetry.

The romantic Lied established itself with Schubert. In his remarkable study published in the magazine Diapason, musicologist Sylvain Fort demonstrated that with Schubert we were witnessing a total transfiguration of the Volkslied (the “song of the people,” with its nuance and strong folklore connotations). A triple revolution took place, not only in politics and the imagination but also in performing. Henceforward, the Lied symbolised Romanticism’s relationship with the world. To underline the poetic revolution, we can point to Schubert’s friendly ties with the poets Mayrhofer (an Austrian) and Schober (born in Sweden to Austrian parents), and the sureness of the literary tastes of Schumann and Wolf.

The combination of voice and piano

Roland Barthes, who took singing lessons and hated the bourgeois pomposity in the voice of a Gérard Souzay, once commented in a radio programme: “In opera, it is the sexual timbre of the voice that is important; in the Lied, it is the tessitura that counts. So here, no excessive notes, no cries or outbursts, no physiological prowess. The tessitura is that modest space of the sounds that each of us can produce, and within whose limits it is possible to fantasise about the reassuring unity of the body. In all Romantic music, vocal or instrumental, it is the song of the natural body. It is music that has meaning only if I can sing it in my self with my body.” All recordings confirm this; all vocal timbres colour the universe of the Lied, but the extremes in the register that belong more to the world of opera are to be avoided. And so, in the Lied, the vocal technique is most often translated by a fusion between the air and the recitative.

In the literature of the Lied, the melodies are spellbinding and sensual. And the piano never counters the voice. In fact, as musicologist Sylvain Fort nicely puts it, “The piano constantly modulates, and it changes its tone as if in a conversation; it changes key, and the line of the song is constantly infused.” The finality is that the music should always have the last word in the dialogue with poetry. Besides, as the musicologist Hélène Cao has said, the music frees itself from its subjection to the verse in order to take charge of the dramatic and psychological evolution; and the forms are diversified by the changing of the piano part while the singer repeats the melody. It is important to note that all the 19th century composers were gifted pianists, and that this privileged the diversification of their writing, which itself went hand in hand with the diversification of the harmonic language.

Teca CALAZANS and Philippe LESAGE

adapted into english by Martin Davies

Our thanks to the musicologist Hélène Cao, and to Jean Buzelin for his knowledge of Kurt Weill’s Berlin years.

Bibliography: Anthologie du lied, Hélène Cao & Hélène Boisson (Buchet Chastel, Paris)

© 2025 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Discographie

LA VOIX GERMANIQUE - DU LIED ROMANTIQUE AU CABARET BERLINOIS

CD1

1) Ständchen (Schubert – Ludwig Rellstab)

Du recueil Schwannengesang D 957 (Le Chant du Cygne) D 957

Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baryton) Gerald Moore (piano)

7 octobre 1951

78 t HMV DB 21349

2) Abschied (Schubert – Rellstad)

Du recueil Schwanengesang D 957 (Le Chant du Cygne) D 957

Dieter Fisher – Dieskau (baryton) Gerald Moore (piano)

A Schubert Lieder Recital / 1955

LP HMV 1295

3) Gute Nacht (Schubert – Wilhelm Müller)

Recueil Die Winterreise D 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)

Hans Hotter (baryton) Gerald Moore (piano)

Mai 1954

Emi Angel Records 3521

4) Die Post (Schubert – Müller)

Recueil Die Winterreise D 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)

Same as 3

5) Der Leiermann (Schubert – Müller)

Recueil Die Winterreise D 911 (Le Voyage d’Hiver)

Same as 3

6) ErlKönig (Schubert – Goethe) D328

(Le Roi des Aulnes)

Gérard Souzay (baryton) Dalton Baldwin (piano)

Juin 1961

Philips 835 097 AY

7) Ganymed D.544 opus 19 N°3 (Schubert – Goethe)

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano) Edwin Fischer (piano)

Octobre 1952

Columbia 33 CX 1040

8) Im Frühling D.882 (Schubert – Schulze)

Same as 7

9) An Die Music D.547 op 88 N°4 (Schubert – Schober)

Same as 7

10) Gretchen Am Spinnrade D.118 op 2 (Schubert – Goethe)

Same as 7

11) Nachtviolen D752 (Schubert – Mayrhofer)

Same as 7

12) Die Florelle D 550 (Schubert – Schubart)

Gérard Suzay (bayton) Dalton Baldwin (piano)

Juin 1961

Philips 835 097 AY

13) Der Dopplegänger (Schubert – Heine)

Recueil Schwanengesang D.957 (Le Chant du cygne)

Same as 12

14) Die Rose, Die Lilie, Die Taube (Schumann – Henri Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baryton) Jorg Demus (piano)

1960

DG 18370

15) Und Wüssten’s Die Blumen (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

16) Das Ist Ein Flötten Und Geign (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

17) Hoï Ich Das Liedchen Klingen (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

18) Ein Jüngling Liebt Ein Mädchen (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

19) Ich Hab’ Im Traume Geweinet (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

20) Aus Alten Marchen (Schumann – Heine)

Du recueil Dichterliebe op.48 (Les Amours du Poète)

Same as 14

21) Meerfahrt op 96 n°4 (Brahms – Heine)

Dieter Fisher-Dieskau (baryton) Jorg Demus (piano)

1960

DG 18370

22) Der Tod, Das Ist Die Kühle Nacht op 96 n° 1 (Schumann – Heine)

(La mort, c’est la nuit fraiche)

Same as 21

23) Gesang Weylas (Hugo Wolf – Mörike)

Du recueil Mörike-Lieder IHW 22

Christa Ludwing (mezzo -soprano) Gerald Moore (piano)

1957

EMI Columbia 33 CX1552

24) Auf Einer Wanderung (Hugo Wolf – Mörike)

Du recueil Mörike-Lieder IHW 22

Same as 23

25) Mignon (Wolf – Goethe)

Du recueil Goethe-Lieder IHW 10

Imgard Seefried (soprano) Erik Werba (piano)

LP Anthologie du lied (2)

1961

DG 18155

CD2

1) Wenn Mein Schatz Hochzeit Macht (Mahler)

Recueil Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gessellen IGM 5 (chants d’un compagnon errant)

Christa Ludwing (mezzo-soprano) Philarmonia Orchestra, dir Sir Adrian Boult

18 oct 1958

EMI Angel records S 35776

2) Ging Heut’Morgen Übers Feld (Mahler)

Recueil Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gessellen IGM 5 (chants d’un compagnon errant)

Same as 1

3) Im Abendrot (Richard Strauss – Joseph von Eichendorff)

Recueil 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Quatre dernier Lieder)

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano) Philarmonia Orchestra, direction Otto Ackermann

25 Sept 1953

EMI Columbia 33 SC 107I

4) September (Richard Strauss – Herman Hesse)

Recueil 4 Letzte Lieder, TrV 296 (Quatre dernier Lieder)

Same as 3

5) Isoldes Liebestod (Wagner)

Acte 3 de Tristan & Isolde

Christa Ludwig ( mezzo zoprano) Philarmonia Orchestra , dir Otto Klemperer

25 mars 1962

EMI Columbia SAX 2462

6) Seele, Wie Bist Du Schöner (Alban Berg -Peter Altenberg)

(Ame, combien tu es plus belle)

Recueil Fünf Orchestenlieder nach Ansichtskartentexten von Peter Altenberg op 4

Betty Beardslee (soprano) Columbia Symphony Orchestra, direction Robert Craft

5 et 17 juin 1959

Columbia ML 5428 / MF 61035

7) Sahst Du Nach Dem Gewitterregen Den Wald (Berg -Altenberg)

(As-tu vu, après la pluie d’orage)

Same as 6

8) Über Die Grenzen Des All (Berg – Altenberg)

(Par-delà les frontières de l’univers)

Same as 6

9) Nichts Is Gekommen (Berg – Altenberg)

(Rien n’est venu)

Same as 6

10) Hier Ist Friede (Berg – Altenberg)

(Ici c’est la paix)

Same as 6

11) Lulu’s Song (Berg)

De Lulu Suite IAB 4

Helga Pilarczyk (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra, dir Antal Dorati

19 au 22 Juin 1961

Mercury SR -90278

12) La Complainte de Mackie (Kurt Weill – Bertold Brecht)

Extrait de L’Opéra de quat’sous

Wolfgang Neuss (Moritatsanger) / Orchestre des Sender Freies Berlin, direction Wilhelm Brückner – Ruggeberg

1958

CBS 78279

13) Duo de la Jalousie / Eiffersuchtsduett (Weill – Brecht)

Lotte Lenya et Willy Trenk -Trebistch ; Lewis Ruth Band, dir Theo Mackeben

1930

Ultraphon 77752

14) Barbarasong

Lotte Lenya, même formation que 13

15) Surabaya Jonny (Weill – Brecht)

Chanson de Happy End

Lotte Lenya, Theo Mackeben mit seinen Jazz Orchester

Berlin 1929

Orchestrola 2311

16) Bilbao Song (Weill – Brecht)

Chanson de Happy End

Lotte Lenya, même formation que 15

17) Alabama Song (Weill – Brecht)

Extrait de Aufstieg und fall der Stadt Mahagonny

Lotte Lenya & The Three Admirals ; direction Theo Mackeben & His Jazz Orchestra

Berlin 24 février 1930

Ultraphon A 37

18) Denn Wie Man Sich Bettet, So Lieght Man

Same as 17

19) Falling In Love Again (musique : Friedrich Hollaender – texte : Connelly)

Tiré de Der Blaue Engel (L’Ange Bleu)

Marlene Dietrich

6 février 1930

HMV B3524

20) Wenn Die Beste Freundin (Hollaender)

Marlene Dietrich, Margo Lion, Oscar Karlweiss et accompagnement au piano de Mischa Spoliansky

2 juin 1928

Electrola EG 892

21) Jonny (Hollaender)

Marlene Dietrich ; orchestre Peter Kreuder

1931

Ultraphon A887

22) Lili Marlene (musique : Norbert Schultze – texte : Hans Leip & Marlene Dietrich)

Marlene Dietrich ; orchestre Charles Magnante

7 septembre 1945

Decca 73031

23) Das Nachtgespenst (Rudolf Nelson ; texte : Friedrich Hollaender)

Kurt Gerron (chant) Rudolf Nelson (piano)

Mars 1930

Ultraphon Telefunken A388