- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

- Notre Catalogue

- Philosophie

- Philosophes du XXème siècle et d'aujourd'hui

- Histoire de la philosophie (PUF)

- Contre-Histoire et Brève encyclopédie par Michel Onfray

- L'œuvre philosophique expliquée par Luc Ferry

- La pensée antique

- Les penseurs d'hier vus par les philosophes d'aujourd'hui

- Textes philosophiques historiques interprétés par de grands comédiens

- Histoire

- Livres

- Sciences Humaines

- Paroles historiques

- Livres audio & Littérature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jazz

- Blues - R'n'B - Soul - Gospel

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- Chanson française

- Musiques du monde

- Afrique

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- Antilles

- Caraïbes

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexique

- Amérique du Sud

- Tango

- Brésil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Espagne

- Yiddish / Israël

- Chine

- Tibet / Népal

- Asie

- Océan indien / Madagascar

- Japon

- Indonésie

- Océanie

- Inde

- Bangladesh

- URSS / Chants communistes

- Musiques du monde / Divers

- Musique classique

- Compositeurs - Musiques de film - B.O.

- Sons de la nature

- Notre Catalogue

- Jeunesse

- Philosophie

- Nouveautés

- Comment commander ?

- Recevoir le catalogue

- Manifeste

- Dictionnaire

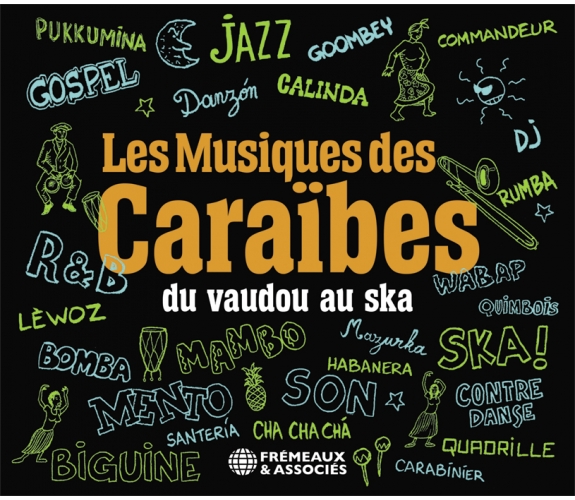

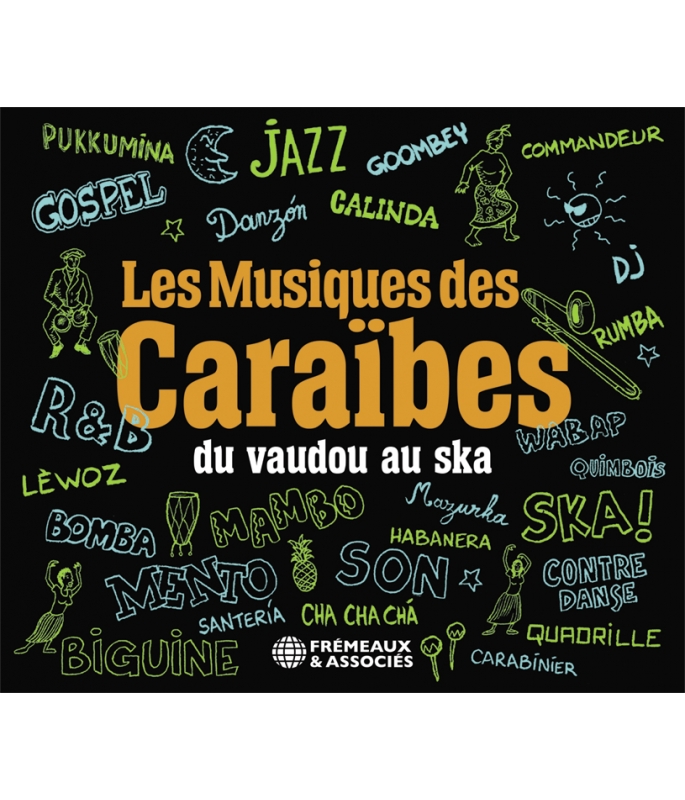

MONGO SANTAMARÍA, BOB MARLEY, HARRY BELAFONTE, ISRAEL “CACHAO” LOPEZ,…

Ref.: FA5799

EAN : 3561302579924

Direction Artistique : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Durée totale de l'œuvre : 2 heures 34 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

MONGO SANTAMARÍA, BOB MARLEY, HARRY BELAFONTE, ISRAEL “CACHAO” LOPEZ,…

- - COUP DE COEUR MUSIQUES DU MONDE DE L'ACADÉMIE CHARLES CROS 2022

- - SELECTION TELERAMA

Merengue, calypso, gombey, goombay, santería, mento, spirituals, gwoka, son, soul jazz, descarga, biguine, pachanga, cha-cha-chá, blues, konpa, contredanse, bomba, shuffle, quadrille, mambo, voodoo, soul, quelbe, worksong, rumba, valse, son montuno…

Négligées, méconnues, ignorées, les musiques caribéennes sont pourtant à la base d’une grande partie des musiques américaines, qui ont conquis le monde. Marquées à leur tour par les États-Unis, elles ont produit une magie irrésistible de Cuba à la Nouvelle-Orléans et de la Martinique à Haïti jusqu’à la Jamaïque. Ce florilège des musiques des îles West Indies paraît simultanément au livre de référence « Les Musiques des Caraïbes » (Le Castor Astral) de Bruno Blum, qui remanie et complète trente livrets de coffrets Caraïbes parus chez Frémeaux et Associés. Il a sélectionné ici la crème des enregistrements fondateurs des styles caribéens de 1949 à 1972 pour cette anthologie de compétition, au très large éventail.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

CD 1 : J. P. MORGAN [BAHAMAS, GOOMBAY] - BLIND BLAKE • CHINESE CHILDREN CALLING ME DADDY [TRINIDAD, CALYPSO] - THE MIGHTY TERROR • TIPITINA [BLUES] - PROFESSOR LONGHAIR • BULLFROG DRESSED IN SOLDIER CLOTHES [BAHAMAS, GOOMBAY] - DELBON JOHNSON • DAY DAH LIGHT [JAMAICA, WORK SONG] - LOUISE BENNETT • STAR O [JAMAICA-USA, WORK SONG] - HARRY BELAFONTE • THE JACK-ASS SONG [NEW YORK, MENTO] - HARRY BELAFONTE • SWEETIE JOE [HAITI-NEW YORK, MERINGUE] - JOSEPHINE PREMICE • OBEAH MAN [VIRGIN ISLANDS, QUELBE]- ALWYN • ISLAND GAL AUDREY [BERMUDA, CALYPSO] - SIDNEY BEAN • TALKING PARROT [JAMAICA, MENTO] - COUNT LASHER • DOCTOR KITCH [TRINIDAD, CALYPSO] - LORD KITCHENER • SOLAS MARKET/WATER COME A MI EYE (COME BACK LIZA) [JAMAICA, MENTO] - THE WRIGGLERS • JACK AND JILL SHUFFLE [JAMAICA, BLUES SHUFFLE] - THEOPHILUS BECKFORD W/ERNEST RANGLIN • MOSES [GEORGIA SEA ISLANDS, SPIRITUAL] - JOHN DAVIS AND THE SPIRITUAL SINGERS OF GEORGIA • HOO-DOO BLUES [LOUISIANA, BLUES] - LIGHTNIN’ SLIM • MUSIC I FEEL [JAMAICA, NYABINGHI BLUES] - COUNT OSSIE & THE WAREIKAS • FREEZIN’ IN NEW-YORK [BERMUDA, GOMBEY] - REUBEN MCCOY • SINNERS WEEP [JAMAICA, SOUL] - OWEN GRAY • THE ANSWER [JAMAICA, SOUL JAZZ] - CECIL LLOYD GROUP W/TOMMY MCCOOK • GROOVIN’ WITH THE BEAT [JAMAICA, SOUL JAZZ] - CECIL LLOYD GROUP W/ROLAND ALPHONSO, DON DRUMMOND • IMPRESSION [JAMAICA-UK, FREE JAZZ] - JOE HARRIOTT QUINTET • CREOLE O VOUDOUN (YANVALOU) [HAITI, VOODOO RITUAL] • DO YOU STILL LOVE ME? [JAMAICA, BLUES SHUFFLE] - BOB MARLEY.

CD 2 : NEGRO MI CHA-CHA-CHÁ [CUBA, CHA CHA CHÁ] - FACUNDO RIVERO • GOZA MI TRUMPETA [CUBA, DESCARGA] - ISRAEL « CACHAO » LOPEZ • IT AIN’T NECESSARILY SO [CUBA-USA, RUMBA] - CAL TJADER • MI SONCITO [CUBA, SON MONTUNO] - CELIA CRUZ • TAMBORES AFRICANOS [CUBA, GUAGUANCÓ, SANTERÍA] - CELINA Y REUTILIO • AY LOLA [PUERTO RICO, PLENA] - CHIQUITIN GARCIA • LAS BATATAS [DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, MERENGUE] - DIORIS VALLADARES • MONTUNO GUAJIRO [CUBA, DESCARGA] - NIÑO RIVERA • SAN LUISERA [CUBA, SON] - GRUPO COMPAY SEGUNDO • LA BOTIJUELA DE JUAN [CUBA, SON] - CONJUNTO SONES DE ORIENTE • CONTRE DANSE N°4 [HAITI, CONTREDANSE/QUADRILLE] - NEMOURS JEAN-BAPTISTE • MIN CIG OU [HAITI, KONPA] - NEMOURS JEAN-BAPTISTE • EL MARINERO [DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, MERENGUE] - DAMÍRON Y CHAPUSEAUX • LA PESADILLA [DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, MERENGUE CARABINIER] - LUIS QUINTERO Y SU CONJUNTO ALMA CIBAEÑA • 15. MAMBO DE CUCO [CUBA, MAMBO] - MONGO SANTAMARIA • 16. CONMIGO [PUERTO RICO, PACHANGA] - EDDIE PALMIERI Y SU CONJUNTO « LA PERFECTA » • 17. WOLENCHE FOR CHANGÓ [CUBA, SANTERIA] - MONGO SANTAMARIA • 18. ORIZA [PUERTO RICO, BOMBA GANGA] - CORTIJO Y SU COMBO • 19. ZOMBIE JAMBOREE [JAMAICA, MENTO] - LORD JELLICOE AND HIS CALYPSO MONARCHS • 20. MAGDALENA [MARTINIQUE, CREOLE WALTZ] - L’ORCHESTRE DELS’ JAZZ BIGUINE • 21. JE PEUX PAS TRAVAILLER [GUADELOUPE-FRANCE, BIGUINE] - HENRI SALVADOR • 22. MON AUTOMOBILE [GUADELOUPE, BIGUINE] - ROBERT MAVOUNZY • 23. PASTOURELLE [GUADELOUPE, COMMANDEUR DE QUADRILLE] - AMBROISE GOUALA • 24. SOULAGE DO A KATALINA [GUADELOUPE, GWOKA] BAILIFF/ROSPOR/REGENT.

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : BRUNO BLUM

COÉDITION : FONDATION POUR LA MÉMOIRE DE L’ESCLAVAGE ET LE CASTOR ASTRAL

BIGUINE - VALSE - MAZURKA CREOLES / 1929-1940

THE AFRO-CUBAN FOUNDING RECORDINGS BEFORE AND AFTER...

DANSES DU MONDE - ESPAGNE, CARAÏBE, AMÉRIQUE DU SUD,...

THE KINGSTON RECORDINGS 1951-1958

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1J.P. MorganBlind Blake And His Royal VictoriaBlake Alphonso Higgs00:02:431951

-

2Chinese Children Calling Me DaddyMighty TerrorMighty Terror00:02:381949

-

3TipitinaLonghair ProfessorHenry Roeland Byrd00:02:241953

-

4Bullfrog Dressed In Soldier ClothesJohnson DelbonDelbon Johnson00:01:511954

-

5Day Dah LightBennett LouiseTraditionnel00:01:251954

-

6Star OBelafonte HarryHarry Belafonte00:02:031956

-

7The Jack-Ass SongBelafonte HarryIrving Burgie00:02:541956

-

8Sweetie JoeJosephine PremiceJosephine Premice00:02:291957

-

9Obeah ManAlwyn Richards And The St Thomas Calypso OrchestraAlwyn Richards00:02:211957

-

10Island Gal AudreyBean SidneyTerence Perkins00:02:441958

-

11Talking ParrotLasher CountCount Lasher00:02:491956

-

12Doctor KitchLord KitchenerAldwyn Roberts00:03:501962

-

13Solas Market Water Come A Mi Eye (Come Back Liza)The WrigglersInconnu00:03:371958

-

14Jack And Jill ShuffleBeckford TheophilusTheophilus Beckford00:03:011960

-

15MosesJohn Davis And The Spiritual Singers Of GeorgiaInconnu00:04:161961

-

16Hoo-Doo BluesLightnin SlimLightnin' Slim00:02:201960

-

17Music I FeelCount Ossie And The WareikasCount Ossie00:02:331961

-

18Freezin' In New-YorkMccoy ReubenReuben McCoy00:02:281960

-

19Sinners WeepOwen Gray With Herson And His City SlickersOwen Gray00:02:261961

-

20The AnswerCecil Lloyd GroupTommy McCook00:07:411962

-

21Groovin' With The BeatCecil Lloyd GroupDon Drummond00:05:281958

-

22ImpressionJoe Harriott QuintetJoe Harriott00:05:281961

-

23Creole O Voudoun (Yanvalou)InconnuTraditionnel00:05:041953

-

24Do You Still Love MeBob MarleyBob Marley00:02:301962

-

PisteTitreArtiste principalAuteurDuréeEnregistré en

-

1Negro Mi Cha-Cha-ChaFacundo Rivero Y Su QuartetoFacundo Rivero00:03:241955

-

2Goza Mi TrumpetaCachao Y Su Ritmo CalienteOsvaldo Estivill00:02:591957

-

3It Ain't Necessarily SoCal TjaderGeorge Gerschwin00:02:031956

-

4Mi SoncitoCelia Cruz Con La Sonora MatanceraIsabel Valdes00:02:391955

-

5Tambores AfricanosCelina Y Reutilo Y Su Conjunto TipicoJulio Blanco Leonard00:02:371956

-

6Ay LolaChiquitin Garcia Y Su TrioDe Jesus00:02:531958

-

7Las BatatasDioris Valladares Y Su Conjunto TipicoEfrain Rivera00:02:521956

-

8Montuno GuajiroNino Rivera's Cuban All StarsNino Rivera00:09:221962

-

9San LuiseraGrupo Compay SegundoManuel Proveda00:02:451957

-

10La Botijuela De JuanConjunto Sones De OrienteMartin Valiente00:02:141962

-

11Contre Danse n°4Nemours Jean BaptisteJean-Baptiste Nemours00:02:161958

-

12Min Cig OuNemours Jean BaptisteJean-Baptiste Nemours00:03:481961

-

13El MarineroDamiron Y ChapuseauxRicardo Rico00:02:471962

-

14La PesadillaMilito Perez W Luis Quintero Y Su Conjunto Alma CibaenaEmilio Nunez00:02:541962

-

15Mambo De CucoMongo Santamaria Y La Playa SextetNicholas Martinez00:03:521959

-

16ConmigoEddie Palmieri Y Su Conjunto La PerfectaEddie Palmieri00:02:451962

-

17Wolenche For ChangoMongo SantamariaSantamaria Mongo00:02:461960

-

18OrizaCortijo Y Su ComboSilvestre Mendez00:03:541962

-

19Zombie JamboreeLord Jellicoe And His Calypso MonarchsLord Intruder00:02:451962

-

20MagdalenaOrchestre Del's Jazz BiguineEugène Delouche00:02:451952

-

21Je peux pas travaillerHenri SalvadorBoris Vian00:03:051958

-

22Mon automobileRobert MavounzyTraditionnel00:03:041966

-

23PastourelleElie CologerTraditionnel00:05:161972

-

24Soulage do a Katalina GwokaPhilippe YéyéTraditionnel00:01:491971

Les Musiques des

Caraibes

du vaudou au ska

Merengue, calypso, gombey, goombay, santería, mento, spirituals, gwoka, son, soul jazz, descarga, biguine, pachanga, cha-cha-chá, blues, konpa, contredanse, bomba, shuffle, quadrille, mambo, voodoo, soul, quelbe, work song, rumba, valse, son montuno…

Négligées, méconnues, ignorées, les musiques caribéennes sont pourtant à la base d’une grande partie des musiques américaines, qui ont conquis le monde. Marquées à leur tour par les États-Unis, elles ont produit une magie irrésistible de Cuba à la Nouvelle-Orléans et de la Martinique à Haïti jusqu’à la Jamaïque. Ce florilège des musiques des îles West Indies paraît simultanément au livre de référence « Les Musiques des Caraïbes » (Le Castor Astral) de Bruno Blum, qui remanie et complète trente livrets de coffrets Caraïbes parus chez Frémeaux et Associés. Il a sélectionné ici la crème des enregistrements fondateurs des styles caribéens de 1949 à 1972 pour cette anthologie de compétition, au très large éventail.

Patrick Frémeaux

Often neglected, unsung and ignored, the music of the Caribbean no less formed the basis of much American music, which subsequently conquered the world. In turn, the USA left a deep mark on it, which produced an irresistible magic - from Cuba to New Orleans and all the way to Martinique, Haiti, Jamaica… Bruno Blum has selected the cream of the founding recordings of different Caribbean styles, recorded between 1949 and 1972, for this high-performance, wide-ranging anthology.

Patrick Frémeaux

LES MUSIQUES DES CARAÏBES

Du voodoo au ska - 1949-1972 Par Bruno Blum

Bahamas – Bermuda - Cuba - Dominican Republic – Guadeloupe - Haiti - Jamaica - Martinique New Orleans - New York - Puerto Rico - Trinidad & Tobago - Virgin Islands

Pourquoi les extraordinaires musiques des Caraïbes ne figurent-elles jamais dans l’histoire de la musique américaine ? Ignorance ? Négligence ? Inconséquence ? Impérialisme culturel ? Racisme ? Pourtant les chants de travail, les spirituals, le jazz, le rap, la salsa, le ska, le calypso, le rythme de Bo Diddley et bien d’autres styles absorbés par le géant américain ont en bonne partie jailli des Caraïbes.

Comprendre la musique américaine, qui a conquis le monde, c’est aussi connaître la musique des Caraïbes. Comprendre la musique populaire internationale moderne demande que l’on se tourne vers les musiques caribéennes. Les apprécier c’est danser au son du merengue, méditer sur la pulsation du blues nyabinghi rasta de Count Ossie, planer sur le jazz de Louisiane, le compas haïtien ou le jazz cubain, le fabuleux descarga (représenté ici par les envoûtants Goza Mi Trompeta de Cachao y Su Ritmo Caliente et Montuno Guajiro par Niño Rivera’s Cuban All Stars).

Des musiques originales, très variées, sont parties des villages et café-concerts des Caraïbes. Elles ont forgé les musiques du monde : la rumba cubaine (en fait un nom global pour plusieurs styles cubains, dont le son) est devenue l’immensément populaire rumba congolaise, le ska jamaïcain a connu un succès planétaire par le truchement d’une mode anglaise de 1980. Et que dire de la salsa new-yorkaise, née dans la communauté hispanophone de New York, mélange de musiques portoricaines, domi- nicaines et cubaines ? Des succès biguine d’Henri Salvador, qui tourna en dérision la proverbiale flemme des Antillais avec son Je peux pas travailler écrit avec Boris Vian ? Des mutations numériques du compas haïtien, encore bien présentes sur les pistes de danse des Antilles au XXIe siècle ? Ou encore du rap, que des Jamaïcains ont popularisé dans le Bronx, héritier direct de la tradition des commandeurs de quadrille qui dirigeaient la danse et dont le Pastourelle guadeloupéen d’Ambroise Gouala est un indice inclus ici1 ?

En retour, les États-Unis ont tout autant influencé la musique des îles. Blues jamaïcain, jazz antillais, descarga cubaine, merengue dominicain gravé à New York… et bien plus encore. Partout on retrouve deux constantes de la musique créole : une tendance à la pulsion hypno- tique, héritée de la transe des religions animistes afro- caribéennes, et des performances personnelles, des passages de solos où l’interprète attire tous les regards — et les oreilles — pendant son intervention.

Cette anthologie présente une synthèse des genres fon- dateurs des musiques caribéennes modernes, des trésors enregistrés pour la première fois au milieu du XXe siècle : avant le grand mix des années 60 auquel ces disques novateurs et variés ont largement contribué. Ils sont aussi essentiels que négligés.

CRÉOLE

La culture créole est issue de la conquête des Amériques. Elle résulte d’un brassage de populations d’origines très diverses, notamment suite à la déportation d’un grand nombre Africains. Elle s’étend des Bermudes à la Trinité et de la Martinique à la Nouvelle-Orléans ; elle se retrouve au Texas et bien au-delà, jusque dans les villes du nord comme New York où les descendants d’esclaves étaient partis chercher la rédemption. Plusieurs titres de cette anthologie ont été enregistrés à New York : les Cubains fuyant la révolution de 1959, les Dominicains fuyant la dictature, des Portoricains, Jamaïcains, Haïtiens cherchant une vie meilleure s’y sont installés en force. La créolité passe aussi par le Mississippi, la Georgie, le Tennessee et au sud elle s’étend jusqu’à la Colombie, le Brésil, etc. Aux Caraïbes mêmes, les Îles Vierges et Porto Rico ne sont-ils pas des territoires des États-Unis ? Et comme Saint-Domingue, Cuba a longtemps été un protectorat américain dont la base américaine de Guantanamo reste une cicatrice.

La matrice créole des Caraïbes a produit un mélange de cultures unique au monde. Elle a apporté une myriade de musiques rituelles, de rythmes, de traditions, de mélodies, de styles, de danses et de pratiques exposés ici. Certaines sont de véritables musiques racines, comme les chants de travail (écouter Day Dah Light venu de Jamaïque), les spirituals chrétiens (comme Moses, venu des îles Sea de Georgie) et les coutumes festives au son du tambour comme le gwoka guadeloupéen Soulagé Do A Katalina des danses lèroses (lèwoz), que l’on retrouve aussi à Haïti2. Tous ces styles utilisent le principe de l’appel-réponse caractéristiquement africain : le meneur prononce un vers, la chœur répète en rythme. On retrouve ce schéma dans beaucoup de morceaux ici.

Les musiques européennes étaient principalement inter- prétées par les esclaves de maison, des domestiques à qui la musique était enseignée (quadrille, contredanse, danzón et boléro espagnol, etc.). Les apports européens se sont ainsi fondus dans la création de musiques créoles, c’est à dire un mélange africain, européen avec, dans une moindre mesure, une présence amérindienne et asiatique.

On trouve ici un exemple parlant de cet héritage européen dans une contredanse, une musique française créolisée, avec son commandeur francophone (qui dirigeait la danse en parlant, selon la tradition en vigueur à la cour de Louis XVI) et un rythme de tambour syncopé (Contre Danse n°4 de Nemours Jean-Baptiste à Haïti). Le quadrille était très populaire aux Amériques (Pastourelle avec le commandeur Ambroise Gouala à la Guadeloupe), la meringue, le carabinier, la fanfare, la valse (Magdalena par le Martiniquais Eugène Delouche) ou la mazurka ont également perduré dans des versions fortement, magnifiquement créolisées.

Ce processus de fusion a été analogue dans différentes régions américaines et dans les Caraïbes. Néanmoins l’isolement des îles a produit des développements différents, idiosyncratiques, en fonction de l’histoire, des ethnies et des cultures dominantes de chaque région.

En règle générale, seuls les chants de travail étaient tolérés car ils amélioraient la productivité des esclaves aux champs. Cependant les captifs africains avaient apporté avec eux différents rites animistes, leurs rythmes et leurs chants longtemps interdits. Ils ont aussi recréé plusieurs instruments africains. Schématiquement les musiques de nature africaine ont été autorisées de façon très restreinte dans les colonies catholiques : les cabildos espagnols à Cuba, sorte de centres culturels pour esclaves et les macumbas portugaises similaires au Brésil. À la Nouvelle- Orléans, le légendaire Congo Square était une attraction touristique où l’on venait voir les esclaves jouer, danser et chanter jusqu’au début du XIXe siècle et au-delà.

Les prières et chants spirituals chrétiens étaient interdits aux esclaves. Ils ont lentement commencé à être autorisés à partir de 1800 et ont été mieux acceptés après les abolitions de l’esclavage : écouter Moses par John Davis and the Spiritual Singers of Georgia, un spiritual chantant la libération par Moïse des esclaves du joug du pharaon, tel qu’il est conté dans le livre de L’Exode. L’authentique arrangement vocal d’origine de ce spiritual a été préservé, c’est rare, des influences ultérieures jazz, gospel, etc. dans les petites îles Sea isolées sur le littoral de Georgie, au nord de la mer des Caraïbes.

ANIMISME

Dans nombre de religions africaines, des divinités sont présentes dans toute chose (animisme) : divinité de la mer, du feu, de la guerre, du carrefour, etc. Dans les états américains, les expressions animistes des esclaves ont longtemps été considérées « diaboliques » et lourdement réprimées jusqu’au XXe siècle. Même histoire aux Caraïbes. Avec la progression des religions chrétiennes chez les Afro-Américains au XIXe siècle et avec l’arrivée tardive de Bantous avant et après les abolitions, les croyances d’origine africaine ont été mieux tolérées. Les Afro-Caribéens ont fait coexister leurs croyances animistes (le hoodoo américain par exemple, très mal considéré par tous les Chrétiens) et chrétiennes (méthodistes, baptistes, pentecôtistes, etc.) pourtant réputées aussi incompatibles que l’eau et le feu.

En Jamaïque, l’obeah (spiritualité Igbo, est Nigeria actuel) considéré néfaste, source d’envoûtements malveillants, est resté un tabou combattu par les guérisseurs myal ; idem aux Îles Vierges américaines, où Alwyn Richards cherche un désenvoûteur qui « éloigne le vaudou de lui » dans Obeah Man. On retrouve cette crainte avec le quimbois en Martinique par exemple. Mais si la fréquentation des temples protestants en Jamaïque et ailleurs est la norme, la croyance en des forces occultes « animistes » n’en est pas moins forte. Il existe des expressions musicales afro-jamaïcaines rituelles, bien différentes de celles du voisin haïtien, et bien plus respectées, comme le kumina, un héritage bantou à la racine des tambours nyabinghi rastafariens3.

Le vaudou originel est venu de la région d’Abomey au Bénin actuel : Ewe, Yorubá et Fon. Il est arrivé aux Caraïbes avec les bateaux négriers. Le vaudou s’est mélangé avec les rites des autres ethnies, notamment des Bantous arrivés plus tard et dont les pratiques ont par conséquent été plus influentes car moins réprimées. Appelé candomblé et macumba au Brésil, obia au Suriname, obeah en Jamaïque, vodou à Haïti et santería à Cuba, l’animisme est représenté ici avec les fascinants chants et tambours d’un authentique rite vaudou haïtien yanvalou, Creole O Vaudoun, gravé en 1953 par la réalisatrice de cinéma d’avant-garde Maya Deren. L’influence des chants de travail et des rites animistes a ressurgi dans les musiques populaires de toutes les Caraïbes.

Culturellement, la presqu’île de la Nouvelle-Orléans est une île des Antilles — entre la mer des Caraïbes et les États-Unis. Elle est un carrefour des cultures, un port comme Gulfport dans le Mississippi ou Miami en Floride — et Port-au-Prince à Haïti ou Port-of-Spain à la Trinité. C’est pourquoi Lightnin’ Slim chante ici le vaudou de Louisiane dans Hoo-Doo Blues ; il évoque ce thème très mal vu tout comme le Jamaïcain Lord Jellicoe, qui raconte avec humour une fête réunissant les zombies du cimetière dans Zombie Jamboree. Oui, l’histoire du blues de Robert Johnson est un peu la même que celle des troubadours cubains de la campagne comme Celina y Reutilio qui chantaient les divinités yorubás (les orishas) de la santería dans leur Tambores Africanos… en déguisant le nom de Changó en Santa Barbara selon la tradition syncrétique locale. En revanche le grand percussionniste cubain Mongo Santamaría et son équipe chantent ouvertement le dieu des tambours, du tonnerre et des éclairs dans l’incantation Wolenche for Changó. Les orishas sont aussi évoqués dans Oriza du portoricain Cortijo avec le légendaire chanteur Ismael Rivera.

JAZZ BLUES SOUL

La transe induite par les rites était propice à des impro- visations vocales guidées, dit-on, par les esprits, la glossolalie (speaking in tongues). Elle sont, sans doute avec le klezmer d’origine européenne4, à l’origine de l’improvisation dans le jazz ; les musiques rythmées que l’on appelait le jazz au début du XXe siècle étaient présentes dans toutes les Caraïbes — dans toute la culture créole. Et donc pas seulement à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Les formes musicales variaient d’une île à l’autre, d’une ville à l’autre, mais on peut assurément affirmer que le jazz du début du XXe siècle était une musique créole commune à toutes les Caraïbes. L’improvisation dans le jazz afro-américain de Louisiane n’a été enregistrée qu’à partir de 1923 avec Bechet, Johnny Dodds, Louis Armstrong. Mais on retrouve également une culture de l’improvisation dans des disques de biguine (le remarquable Stellio enregistré dès 19295, puis Ernest Léardée, etc.). La plupart des premiers enregistrements caribéens ont été tardifs (années 1940-50) mais on retrouve l’esprit très rythmé du jazz dès 1912 dans les premiers disques gravés à la Trinité — avant le jazz américain enregistré, et avant l’arrivée de l’improvisation dans les enregistrements de jazz (1923)6.

Il est donc naturel que le triomphe du jazz aux États-Unis, qui était emblématique de la culture afro-américaine, ait inspiré des Caribéens. L’orchestre cubain de Machito à New York a mené des jazzmen comme Dizzy Gillespie ou Charlie Parker à improviser sur des rythmes cubains dès les années 1940 et, peu après, les Cubains ont à leur tour enregistré des chefs-d’œuvre du genre jazz « descarga » (Goza Mi Trom- peta, Montuno Guajiro, Mambo de Cuco). Les pièces instrumentales avec des ornementations libres et des improvisations abondent dans la biguine (Mon Auto- mobile de l’irrésistible saxophoniste Robert Mavounzy), la valse et la mazurka martiniquaise et guadeloupéenne (Magdalena). On retrouve une dimension d’improvisation dans l’implacable musique de danse qu’était le merengue dominicain (Las Batatas, El Marinero) ; à Porto Rico, dans la plena (Ay Lola) très proche du merengue, la bomba (Oriza) et la pachanga (l’excellent Eddie Palmieri à ses débuts en 1962 sur Conmigo). Cette excellence latine, à son tour, a inspiré des musiciens états-uniens comme Cal Tjader à enregistrer des compositions américaines avec des arrangements cubains (It Ain’t Necessarily So)7 et caribéens.

Des Jamaïcains ont aussi gravé d’excellents disques de jazz : sur fond de tambours rastas comme Count Ossie & The Wareikas ou dans une veine très proche du soul jazz des États-Unis comme Cecil Lloyd avec les célèbres Don Drummond et Roland Alphonso (Groovin’ With the Beat). On retrouve ces derniers avec le grand guitariste jamaïcain Ernest Ranglin sur The Answer. Ranglin brille également sur un pot-pourri de deux chansons traditionnelles, SolasMarket/Water Come to Mi Eye avec le groupe de mento jamaïcain The Wrigglers. Mais c’est peut-être le remarquable Joe Harriott et son bassiste jamaïcain, des pionniers du free jazz basés à Londres, qui ont le plus brillé dans le domaine du jazz jamaïcain.

Île mystique par excellence, la Jamaïque a très tôt été très marquée par les cantiques et les spirituals chrétiens. Il est donc naturel qu’on y ait enregis- tré des spirituals et de la pure soul, qui en découle (Sinners Weep d’Owen Gray dès 1961). Et bien sûr du blues : Theophi- lus Beckford est représenté ici avec Ernest Ranglin dans un blues shuffle, qui a une dette en- vers Rosco Gordon, Professor Longhair et les États-Unis autant que Tipitina, le classique de Professor Longhair à la Nouvelle-Orléans, a une dette envers les Caraïbes. Un titre rare de Bob Marley, la face B de son tout premier et obscur 45 tours en 1962, est inclus ici. Son style blues shuffle est caractéristique du son en vogue en Jamaïque à cette époque. Le shuffle s’est métamorphosé en ska en 19638.

CALYPSO

Le succès de « Rum and Coca-Cola, » la reprise d’un calypso par les Andrews Sisters en 1945, a contribué à lancer la mode tropicale qui a suivi : mambo et cha-cha-chá cubain (le délicieux Negro mi cha-cha-chá de Facundo Rivero), et calypso trinidadien en particulier9.

L’histoire du blues est un peu la même que celle des chansonniers du mento jamaïcain, aux paroles élaborées, proches du calypso de la Trinité. Comme Elvis Presley avec le rock afro-américain la même année, en 1956 Harry Belafonte a fait des chansons de l’île de ses parents des succès internationaux dans les grands studios RCA de New York (album Calypso, en réalité du mento jamaïcain). Deux d’entre eux sont inclus ici : The Jack-Ass Song et le chant de travail des dockers, qui attendaient la première étoile de la nuit pour cesser le travail, Star-O. Il est précédé par une version plus ancienne de la même chanson par la grande conteuse jamaïcaine Louise Bennett, et intitulée Day Dah Light.

Les Caraïbes étaient connues, à juste titre, pour leurs chansons salaces, aux paroles bien écrites, humoristiques, évoquant la vie au soleil sous les palmiers, les beaux fruits tropicaux - y compris les beaux fruits de jeunes femmes dont les tenues légères évoquaient des mœurs tout aussi légères, fantasme récurrent de tant d’États-Uniens frustrés par le puritanisme. On y entendait d’hilarantes histoires d’amants dans le placard comme Talking Parrot par le maître du mento jamaïcain Count Lasher ou Chinese Children Calling Me Daddy par le Trinidadien The Mighty Terror. La biguine Je peux pas travailler d’Henri Salvador et le célèbre et osé Doctor Kitch du Trinidadien Lord Kitchener sont du même tonneau. Idem pour la description de Island Gal Audrey la reine du polyamour par Sidney Bean aux Bermudes et le Sweetie Joe de la Haïtienne-Américaine Josephine Premice.

L’humour des Bermudes rapporte un voyage aux États-Unis en plein hiver avec Freezin’ in New York et l’exquis Blind Blake, roi du goombay bahaméen, raconte une soirée où son invitée avait un appétit si grand qu’elle pourrait ruiner un millionaire (J.P. Morgan). Même dérision pour Zombie Jamboree, chanson emblématique des Caraïbes, dont il existe d’innombrables versions10. Plus énigmatique mais également savoureux, Bullfrog Dressed in Soldier Clothes est venu des cabarets de Nassau aux Bahamas. En raison de la vogue pour le « calypso » de cette époque, toutes ces chansons ont été vendues sous l’étiquette calypso.

À Porto Rico, Cuba ou en République Dominicaine hispa- nophones, les chansons latines étaient nettement plus tour- nées vers les beaux sentiments, plus politiquement corrects (comme dans le son montuno cubain Mi Soncito de la reine Celia Cruz, exilée aux États-Unis comme beaucoup de musiciens cubains après la révolution de 1959). Milito Perez, lui, raconte son cauchemar dans La Pesadilla, un merengue dominicain au rythme calibré pour une danse de type « carabinier », bien différent du merengue classique, très entraînant comme sur Las Batatas ou El Marinero.

En 1997, le Buena Vista Social Club avec Compay Segundo a voulu faire revivre la magie du son cubain d’avant la révolution. Le succès international de leur album, puis du film que leur a consacré Wim Wenders en 1999 alors que Compay avait déjà 92 ans, a remis la musique cubaine de l’âge d’or des années 1950 sur la carte des musiques du monde. En 1957, le Grupo Compay Segundo avait gravé San Luisera dans ce style son aux harmonies vocales irrésistibles, tout comme le Conjunto Sones de Orientes avec leur La Botijuela De Juan.

Quant au savoureux konpa haïtien créé par Nemours Jean-Baptiste à la même époque (Min Cig Ou), il a depuis conquis toutes les Caraïbes et tient son rang plus d’un demi-siècle plus tard, notamment avec le succès konpa « Déchiré Kilot » par Top Digital en 2018.

Bruno Blum, mars 2021.

Remerciements à Nono Nobour.

© 2021 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1 Bruno Blum, Le rap est né en Jamaïque (Le Castor Astral, 2009).

2 Lire le livret et écouter « Congo Larose Dance » (three drums) sur Haiti - Vodou, Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (Frémeaux et Associés-Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac FA5626).

3 Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Folk-Trance-Possession 1939-1961,

Mystic Music From Jamaica, Roots of Rastafari (FA 5384, et prix de l’Académie Charles Cros 2013) dans cette collection.

4 Lire le livret et écouter Klezmer - American Recordings 1909-1952

(FA 5782).

5 Lire le livret et écouter Stellio, le créateur de la biguine à Paris, intégrale chronologique 1929-1931 (FA 023).

6 Lire le livret et écouter Trinidad 1912-1941 (Harlequin HQ CD 16, 1992) et « Bajan Girl » de Lionel Belasco sur Caribbean in America 1915-1962 dans cette collection (FA 5664).

7 Lire les livrets et écouter les coffrets Cuba in America 1939-1962 (FA 5648) et Caribbean in America 1915-1962 (FA 5664) dans cette collection.

8 La face A de ce premier 45 tours de Bob Marley, « Judge Not », figure dans Jamaica-USA Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) dans cette collection.

9 La version originale de « Rum and Coca-Cola » par Lord Invader figure dans Trinidad - Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) dans cette collection. La version des Andrew Sisters dans le coffret Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde vol. 2, disque 9 Calypso (FA 5342).

10 Retrouvez d’autres versions de « Zombie Jamboree » (alias « Jumbie Jamboree » et « Back to Back ») sur Bahamas Goombay par Vincent Martin & His Bahamians (FA 5302), sur Jamaica - Folk, Trance, Possession par Lord Foodoos (FA 5384), sur Voodoo in America par le Kingston Trio (FA 5375) et Slavery in America par les Talbot Brothers (FA 5467) dans cette collection.

Le livre du même nom, «Les Musiques des Caraïbes », du même auteur a paru au Castor Astral simultanément à ce coffret de deux disques. Il est basé sur les textes de la collection de coffrets CD Caraïbes de Frémeaux & Associés remaniés, augmentés et mis à jour. Chacun des chapitres du livre correspond donc à un coffret de deux ou trois CD (une trentaine de volumes). On peut écouter ici quelques-uns des meilleurs extraits de cette collection Caraïbes, un florilège concocté par l’auteur de la musique fondamentale des Caraïbes de 1949 à 1972.

THE MUSIC OF THE CARIBBEAN

From voodoo to ska - 1949-1972 - by Bruno Blum

Bahamas – Bermuda - Cuba - Dominican Republic – Guadeloupe - Haiti - Jamaica - Martinique New Orleans - New York - Puerto Rico - Trinidad & Tobago - Virgin Islands

Why is it that extraordinary Caribbean music is never featured in the history of American music? Ignorance? Neglect? Thoughtlessness? Cultural imperialism? Racism? Yet work songs, spirituals, jazz, salsa, ska, calypso, rap, the Bo Diddley rhythm and many more Caribbean styles share common ground, or were absorbed by American musical culture.

To know Caribbean music is also, then, to understand American music, which later conquered the world. To appreciate it is to dance to the sound of merengue, meditate to Count Ossie’s Rasta nyabinghi blues pulse, daydream to Louisiana jazz, Haitian konpa or Cuban jazz, the fabulous descarga (embodied here by Cachao y Su Ritmo Caliente’s bewitching Goza Mi Trompeta and Niño Rivera’s Cuban All Stars’ Montuno Guajiro).

Original, multi-faceted music emerged from Caribbean villages and cabarets. They shaped world music: Cuban rumba (really a global name for several Cuban styles, including the son) has become the immensely popular Congolese rumba; following a British trend in 1980, Jamaican ska went through a phase of worldwide success. And what could be said of New York’s salsa, born out of a mix of Puerto Rican, Dominican and Cuban music?

What about beguine hits? Such as Henri Salvador’s Je Peux Pas Travailler, co-written by Boris Vian, which mocks proverbial Caribbean laziness. And Haitian konpa’s digital mutations, still going strong on Caribbean dancefloors in the 21st Century? Not to mention rap music, which was popularized in the Bronx by Jamaicans, and is a direct legacy of the set callers, the commandeurs, who directed the dance with their spoken words, as shown in Ambroise Gouala’s Guadeloupean quadrille, Pastourelle1.

In turn, the United States influenced the Caribbean islands’ music to the same degree. Jamaican blues, French Antilles jazz, Cuban descarga, Dominican merengue cut in New York… and much more. Two constant features of Creole music are found everywhere: a tendency to a hypnotic pulse, which is a legacy of the Afro-Caribbean animist religious trances; and personal performances, solo passages where a performer attracts all the attention — and ears — during his contribution.

This anthology presents a synthesis of the founding genres in modern Caribbean music. These are treasures recorded for the first time in the mid – 20th Century, before the great 1960s mix these varied and innovative recordings widely contributed to.

CREOLE

Creole culture is descended from the conquest of the Americas. It is a product of populations of very diverse origins mixing; most notably following the deportation of Africans in huge numbers to the Americas. It spread from Bermuda all the way to Trinidad, and from Martinique to New Orleans. It can be found in Texas and way beyond, up as far as Northern cities, such as New York, where the descendents of slaves had fled seeking redemption.

Several titles from this anthology were in fact recorded in New York by Cubans, who fled the 1959 Communist revolution, Dominicans, fleeing their own dictatorship. Puerto-Ricans, Jamaicans and Haitians in search of a better life also moved there in numbers. The Creole identity is also featured in Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee and all the way down south to Colombia, Brazil, etc. In the Caribbean itself, are not the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico US territory? And, like the Dominican Republic, Cuba was an American protectorate for decades — the US military base of Guantanamo remains a scar —, all that’s left of that particular brand of colonialism.

The Caribbean Creole matrix has produced a mix of cultures that can be found nowhere else. It has brought a myriad of ritual music, rhythms, traditions, melodies, styles, dances and practices, all on display here.

Some are truly roots music, as can be heard in work songs (listen to Day Dah Light from Jamaica), Christian spirituals (such as Moses, from the Georgia Sea Islands) and festive customs set to the sound of drums, like the Guadeloupe gwoka in Soulagé Do A Katalina from lèrose (lèwoz) dances, also found in Haiti2. All of these styles use the typically African ‘call and response’ principle: the leader delivers a verse, the chorus repeats it — on the beat. Many tunes here follow this pattern.

European music was mainly played by house slaves, who performed domestic work as well as playing the music they had been taught: quadrille, contre danse, danzón and Spanish bolero, etc.

This European input soon merged, (as Creole music was created) becoming an African - European mix with, to a lesser extent, a Native American and Asian presence as well.

A revealing example of this European legacy can be found in contre danse, a Creolised French music style featuring its French-speaking commandeur (who led the dance, speaking, according to the Louis XVI court tradition), here with a syncopated drum-driven rhythm (Contre Danse n°4 by Nemours Jean-Baptiste in Haiti). Quadrille was also very popular in the Americas (hear Pastourelle and its commandeur, Ambroise Gouala, in Guadeloupe); meringue, carabinier, fanfare, mazurka, and waltz (listen to Magdalena by Eugène Delouche, from Martinique) also persisted in strong, magnificently Creolised versions.

This fusion process was analogous in several Caribbean and US regions. Nevertheless, according to their individual histories, ethnicities and the prevailing local cultures and customs, the islands’ isolation from each other produced various idiosyncratic developments.

As a general rule, only work songs were tolerated by the authorities in these territories - because they improved productivity. However, the African captives had brought along with them various animist rituals, rhythms and chants that were long prohibited. They also recreated several African instruments. Basically, music of an African nature was very restricted, but was permitted in Catholic colonies: Spanish cabildos in Cuba, a kind of cultural center for slaves, and similar Portuguese macumbas in Brazil. In New Orleans, the legendary Congo Square was a tourist attraction, where one came to watch slaves play, dance and sing, right up until the beginning of the 19th Century and beyond.

Prayers and Christian spirituals were forbidden to slaves, but these spiritual songs slowly began to be permitted, from around 1800 onwards, and were better accepted after the abolition of slavery in the USA: listen to Moses by John Davis and the Spiritual Singers of Georgia, a spiritual chanting the release of the Pharoah’s slaves by Moses, as told in the book of Exodus in the Bible.

The authentic, original vocal arrangement of this spiritual was preserved from outside influences (i.e. jazz, gospel, etc.), which is a rare occurrence featured on the small, isolated Georgia Sea Islands, north of the Caribbean Sea.

ANIMISM

According to a number of African religions, deities are present in all things (animism): deities of the sea, fire, war, crossroads, etc. In American States, animist expressions by slaves were long thought of as “diabolic” and heavily repressed, right up until the 20th Century. It’s the same story in the Caribbean.

With the progress of Christian religions within the Afro- American communities in the 19th Century, and following the belated arrival of Bantus before and after the various abolitions of slavery, beliefs of African origin began to be better tolerated. Afro-Caribbeans managed to have their animist beliefs (i.e. American hoodoo, deemed horrific by all Christians) somehow coexist with their Christian ones (Methodist, Baptist, Pentecostal, etc.), although both were reputedly as incompatible as fire and water.

In Jamaica, obeah (Igbo spirituality, from present-day eastern Nigeria) is believed to be nefarious, a source of evil spells, and has remained a taboo fought by myal healers. The same goes in the US Virgin Islands, where Alwyn Richards is looking for someone to “take away the voodoo” from him. This fear is also found in Martinique quimbois, for example. However, although attending churches is the norm in Jamaica and elsewhere, the belief in occult, “animist” forces is no less strong. There are also some ritualistic, Afro-Jamaican musical expressions, such as the kumina Bantu legacy at the root of Rastafarian nyabinghi drums3.

The original voodoo came from the Abomey area in present- day Benin: Ewe, Yorubá and Fon. It reached Caribbean shores through the slave traders’ boats. Voodoo mixed with other ethnic rituals, including those of the Bantus, who arrived later, and who, as a result, had more influential practices because they were less suppressed. Called candomblé and macumba in Brazil, obia in Suriname, obeah in Jamaica, vodou in Haiti and santería in Cuba, animism is featured here with the fascinating chants and drums of a genuine Haitian yanvalou voodoo ritual, Creole O Vaudoun, recorded in 1953 by avant-garde cinema director Maya Deren. The influence of work songs and animist rituals surfaced in popular music throughout the Caribbean.

Culturally speaking, the New Orleans peninsula is an Antilles island — situated between the Caribbean Sea and the USA. It is a crossroads of cultures, and it is also a port, like Gulfport in Mississippi, Miami in Florida, Port-Au-Prince in Haiti or Port- Of-Spain in Trinidad.

This is why Lightnin’ Slim is singing Louisiana’s voodoo in Hoo-Doo Blues. He is alluding to this frowned-upon theme; and so is Lord Jellicoe, who tells the story of a party bringing together the zombies of a cemetery, with plenty of humour, in Zombie Jamboree. And yes, the history of Robert Johnson’s blues is a little bit similar to Cuban country troubadours Celina y Reutilio, who sang the Yoruba santería deities (the orishas) in their own Tambores Africanos, disguising the name of Changó as Santa Barbara, according to the syncretic, local tradition. On the other hand, the great Cuban percussionist, Mongo Santamaría and his team, are openly chanting an incantation to the god of drums, thunder and lightning in Wolenche for Changó. Orishas are also alluded to in Oriza by Puerto-Rican leader Cortijo and his legendary singer Ismael Rivera.

JAZZ - BLUES - SOUL

Trance, fuelled by rituals, favoured vocal improvisations guided, so some say, by the spirits themselves (speaking in tongues). These were (perhaps as well as klezmer music of European origins4), at the root of improvisation in jazz. The rhythmic style of the music called jazz, in the early 20th Century, existed in all of the Caribbean — and in all of Creole culture.

So not only in New Orleans. Musical forms varied from one island to another, but it can assuredly be said that early twentieth century jazz was a Creole music common to all of the Caribbean. Improvisation in Louisiana’s African - American jazz was first recorded in 1923, by Sidney Bechet, Johnny Dodds and Louis Armstrong. But a culture of improvisation can also be found in beguine records (the remarkable Stellio was recorded as early as 19295, followed by recordings by Ernest Léardée, et al). Most of the earliest Caribbean recordings were belated (not appearing until the 1940s and 1950s) but the very rhythmic spirit of early jazz can be found as early as 1912 in the first recordings made in Trinidad — before recorded American jazz, and before improvisation was even present in recorded jazz6.

It is therefore only natural that the later triumph of jazz in the USA, which was emblematic of African-American culture, in turn inspired Caribbean musicians. In New York, Machito’s Cuban Orchestra led jazzmen such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker to improvise over Cuban rhythms as early as the 1940s and, returning the favour, Cubans soon after recorded some masterpieces of their own “descarga” brand of jazz (Goza Mi Trompeta, Montuno Guajiro and Mambo de Cuco).

Instrumental pieces with free ornamentation and impro- visation abound in Guadeloupe and Martinique beguine (Mon Automobile by the compelling saxophone player Robert Mavounzy), waltz (Magdalena) and mazurka. There is also a dimension of improvisation in Dominican merengue (Las Batatas, El Marinero).

There was also improvisation in Puerto Rico, around this same time period, where the local plena (Ay Lola) sounds close to the merengue, bomba (Oriza) and pachanga (the excellent Eddie Palmieri’s early recording from 1962, Conmigo). This Latin excellence inspired US musicians like Cal Tjader to record American compositions with Caribbean and Cuban-styled arrangements (It Ain’t Necessarily So)7.

Some Jamaican musicians also recorded brilliant jazz; to a Rastafarian drum beat like Count Ossie & The Wareikas did, or in a vein closer to US soul jazz, as did Cecil Lloyd with the famous Don Drummond and Roland Alphonso (Groovin’ With the Beat). The latter three can also be found alongside great Jamaican guitar player Ernest Ranglin on The Answer. Ranglin also shines on a traditional song medley, Solas Market/Water Come to Mi Eye, with Jamaican mento band The Wrigglers. But perhaps it is the remarkable Joe Harriott and his Jamaican bass player (both free jazz pioneers based in London) who recorded the greatest Jamaican jazz of all (Impression, 1960).

A mystical island par excellence, Christian hymns and spirituals made a mark on Jamaica early on. It is therefore natural that spirituals and some ensuing, genuine, soul music was recorded there (Owen Gray’s Sinners Weep, as early as 1961). And, of course, some blues, too: Theophilus Beckford is featured here with Ernest Ranglin in a blues shuffle, which owes a debt to Rosco Gordon, Professor Longhair and the US in general — as much as Professor Longhair’s classic from New Orleans, Tipitina, owes the Caribbean. There is also a rare track by Bob Marley, the B-side of his very first 45 RPM record, from 1962, included here. His blues shuffle style is typical of the popular sound in Jamaica at the time. The shuffle, of course, had morphed into ska by 19638.

CALYPSO

The success of “Rum and Coca-Cola,” a 1945 calypso cover by The Andrews Sisters, contributed to launching the tropical trend that followed: Cuban mambo and cha-cha-chá (enjoy Facundo Rivero’s exquisite Negro Mi Cha-cha-chá) and Trinidadian calypso in particular9. The history of the blues mostly parallels Jamaican mento songsters’, who sang elaborate lyrics in a style close to Trinidadian calypso.

Much like Elvis Presley did with African-American rock and roll that same year, 1956, Harry Belafonte turned traditional songs from his parents’ island into international hit records, which were recorded in RCA’s big New York City studios, too (his Calypso album was, in fact, Jamaican mento). Two of his songs are featured here: The Jack-Ass Song and Star-O, a docker’s working song, calling for the first star of the night to appear and signal the end of working hours. It is preceded here by an older recording of the same song, Day Dah Light, performed by the great Jamaican storyteller Louise Bennett.

Caribbean music lyricists were, quite rightly, known for their bawdy, salacious songs, which featured well-written, humourous lyrics, telling of life in the sun under the palm trees, enjoying exotic tropical fruits — including the equally exotic fruits of scantily-clad young ladies and their equally slight morals, a recurring fantasy for so many frustrated men in puritanical, Christian America.

One could hear hilarious stories of extra-marital affairs, such as Talking Parrot by Jamaican mento master Count Lasher, or Chinese Children Calling Me Daddy by Trinidadian calypso songster The Mighty Terror. Henri Salvador’s beguine Je Peux Pas Travailler and the famous, risqué, Doctor Kitch by Trinidadian calypso king, Lord Kitchener, are of the same ilk. The same goes for Haitian/American Josephine Premice’s Sweetie Joe, as well as Sidney Bean’s depiction of Island Gal Audrey, who, apparently, was the polygamous ‘Queen of Bermuda.’ Bermudian humour also relates a travelling story taking place in the American winter, Freezin’ in New York, and the exquisite Blind Blake, ‘king of Bahamian goombay’, recalls an evening out where his guest had such an appetite she could “break a millionaire” (J.P. Morgan). The same derisory, but exquisitely satirical, ambience informs Zombie Jamboree, a classic Caribbean song recorded many times10. Also salty, but far more enigmatic, Bullfrog Dressed in Soldier Clothes, comes from the cabarets of Nassau, capital of The Bahamas. All of these songs were branded ‘calypso’ to cash in on the calypso trend of the time.

In Spanish-speaking Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Dominican Republic, Latin songs tended to be more politically-correct, well- intentioned and sentimental, as in son montuno Mi Soncito, sung by Cuban music queen, Celia Cruz, who (like many other Cuban musicians), went into exile in the US after the Castro revolution of 1959. Milito Perez recalls his nightmare in La Pesadilla, a Dominican merengue with a “carabinier” dance rhythm. This is unlike most basic merengue, where a very compelling dance rhythm is featured, as heard on Las Batatas and El Marinero.

In 1997, the Buena Vista Social Club, featuring Compay Segundo, revived the magic of pre-revolution Cuban son music. Their album’s international success, and the Wim Wenders movie that followed (in 1999, by which time Segundo was 92!), put 1950s Cuban ‘golden age’ music back on the World Music map. In 1957, the Grupo Compay Segundo had recorded San Luisera, in that exact, compelling vocal harmony son style, just like the Conjunto Sones de Orientes had also done with La Botijuela De Juan.

As for the charming Haitian konpa created by Nemours Jean- Baptiste around the same time (Min Cig Ou), the konpa style has since conquered everywhere in the Caribbean, maintaining its position, even over half a century later, with, for example, the 2018 big hit, “Déchiré Kilot” by Top Digital.

Bruno Blum, March, 2021.

With thanks to Nono Nobour, and Chris Carter for proof- reading.

© 2021 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1 Bruno Blum, Le Rap Est Né en Jamaïque (Le Castor Astral, 2009).

2 Read the booklet and listen to «Congo Larose Dance (Three Drums)» on Haiti - Voodoo, Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (Frémeaux & Asso- ciés/Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac FA5626).

3 Read the booklet and listen to the Charles Cros award-winning Jamai- ca - Folk-Trance-Possession 1939-1961, Mystic Music From Jamaica, Roots of Rastafari (FA 5384) in this series.

4 Read the booklet and listen to Klezmer - American Recordings 1909-1952 (FA 5782).

5 Read the booklet and listen to Stellio, le créateur de la biguine à Paris, intégrale chronologique 1929-1931 (FA 023).

6 Read the booklet and listen to Trinidad 1912-1941 (Harlequin HQ CD 16, 1992) and “Bajan Girl” by Lionel Belasco on Caribbean in America 1915- 1962 in this series (FA 5664).

7 Read the booklet and listen to Cuba in America 1939-1962 (FA 5648) and Caribbean in America 1915-1962 (FA 5664) in this series.

8 The A-side of Bob Marley’s first single, “Judge Not”, is featured on Jamaica-USA Roots of Ska 1942-1962 (FA 5396) in this series.

9 Lord Invader’s original version of “Rum and Coca-Cola” is available on Trinidad-Calypso 1939-1959 (FA 5348) in this series. The Andrew Sisters’ version is available on Anthology of Dance Music of the World Vol. 2, Disc 9 Calypso (FA 5342).

10 Find some more “Zombie Jamboree” (alias “Jumbie Jamboree” and “Back to Back”) versions on Bahamas Goombay by Vincent Martin & His Bahamians (FA 5302), Jamaica-Folk, Trance, Possession by Lord Foodoos (FA 5384), Voodoo in America by The Kingston Trio (FA 5375) and Slavery in America by the Talbot Brothers (FA 5467) in this series.

The Music of the Caribbean

From voodoo to ska

Discography

Note: some credits differ from previous releases as more information was researched and found since. Some errors were rectified.

Disc 1

1. J. P. MORGAN - Blind Blake & His Royal Victoria Calypsos

(Blake Alphonso Higgs, Dudley Butler)

Blake Alphonso Higgs as Blind Blake-v, bj; Dudley Butler, guitar; Jack Roker and Chatfield Ward, guitar; George Wilson, bass; Alfred “Tojo” Anderson, maracas; Bertie Lord, drums. Nassau, Bahamas, 1951. Art Records AL3, Florida, USA, 1951. [goombay]

From Bahamas - Goombay FA5302

2. CHINESE CHILDREN CALLING ME DADDY - The Mighty Terror

(Fitzgerald Henry aka The Mighty Terror)

Fitzgerald Henry as The Mighty Terror. Accompaniment by Fitzroy Coleman’s Calypso Band. Melodisc 1033, UK, 1949. [calypso]

From Trinidad - Calypso FA5348

3. TIPITINA - Professor Longhair and His Blues Scholars

(Henry Roeland Byrd)

Henry Roeland Byrd as Professor Longhair-v, p; Lee Allen-ts; Alvin Tyler as Red Tyler-bar s; Walter Nelson as Papoose-g; Edgar Blanchard-b; Earl Palmer-d. Cosimo Matassa’s Studio, New Orleans, Louisiana, November, 1953. Atlantic 1020, New York, USA, 1953. [blues]

Previously unreleased in this series.

More Professor Longhair music is available on Roots of New Orleans Soul FA 5633

4. BULLFROG DRESSED IN SOLDIER CLOTHES - Delbon Johnson

(Delbon Johnson)

Delbon Johnson, vocals; backed by Dirty Dick’s Calypsos. Unknown musicians. Nassau, Bahamas, 1954. Dirty Dick’s Famous Hotel Bar Presents: Delbon Johnson, Art Records, ALP-9, Florida, USA, 1954. [goombay]

From Bahamas - Goombay FA5302

5. DAY DAH LIGHT - Louise Bennett

(traditional, arrangement by Louise Bennett)

Louise Bennet-v; bongos, male and female chorus. Kingston, Jamaica, 1954. Folkways FP846, New York, USA, 1954. [work song]

From Jamaica - Mento FA5275

6. STAR O - Harry Belafonte

(Harry Belafonte, Irving Burgie as Lord Burgess, William Attaway, arranged by Tony Scott)

Milton Hinton, bass; Alexander Cambrelen, congas; Mario Castillo, conga; Ossie Johnson, drums; Herbert Levy, flute; Irving « Lord Burgess » Burgie, Charles Colman, J. Hamilton Grandison, Joseph Lewis, Broc Peters, Sherman Sneed, Herbert Stubbs, John White and Gloria Wynder: vocal chorus; Tony Scott, leader. Produced by Herman Diaz Jr., recorded at Webster Hall, New York City, October 20, 1955. RCA LPM-1248, New York, USA, 1956.

Note: song based on the Jamaican work song “Day Dah Light” (see above). [work song]

From Harry Belafonte - Calypso, Mento, Folk FA5234

7. THE JACK-ASS SONG - Harry Belafonte

(Irving Burgie as Lord Burgess, William Attaway)

Same as above. [mento]

8. SWEETIE JOE - Josephine Premice

(Josephine Premice)

Josephine Premice and her group: Josephine Premice-v; Rudy Kerpays-p; Norman Shobey-bongos; Armstead Shobey-congas. Los Angeles, December, 1956. Calypso, GNP-Crescendo GNP-24, California, USA, 1957. [meringue]

From Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde vol. 2, disc 6: Calypso FA5341

9. OBEAH MAN - Alwyn Richards and the St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra

(Alwyn Richards) Alwyn Richards-v; The St. Thomas Calypso Orchestra: unknown p, as, d, bell, chorus. Saint Thomas, Virgin Islands, USA, 1957. Monogram 844, Florida, USA, 1957. [quelbe]

From Virgin Islands Quelbe & Calypso FA5403

10. ISLAND GAL AUDREY - Sidney Bean

(Terence Perkins aka Count Lasher, adapted by Sidney Bean)

Sidney Bean and his Trio: Sidney Bean-v, g; unknown cl, b, d. Hamilton, Bermuda, 1958. Bermuda Records BLP 2003 & Ber-175-45-A, 1958. [calypso]

From Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso FA5374

11. TALKING PARROT - Count Lasher

(Terence Perkins aka Count Lasher)

Terence Perkins as as Charlie Binger and his Calypsonians-v, g. Musicians unknown-bamboo sax, g, b, d, maracas. Produced by Ken Khouri. Kingston, Jamaica, ca 1956. Kalypso Records RL 15, Jamaica, ca. 1956. [mento]

From Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde vol. 2, disc 6: Calypso FA5341

12. DOCTOR KITCH - Lord Kitchener

(Aldwyn Roberts)

Aldwyn Roberts as Lord Kitchener-v; Accompanied by the Frank Francis Orchestra. Port-Of-Spain, Trinidad, 1962. Telco TW 3170, SP 10357, 1962. [calypso]

Previously unreleased in this series.

More Lord Kitchener is available on Trinidad - Calypso FA5348

13. SOLAS MARKET/WATER COME A MI EYE [aka Come Back Liza] - The Wrigglers

(unknown)

Denzil Laing-g; Roland Alphonso-as; Bertie King-cl; Ernest Ranglin-el g; Denzil Laing-maracas; The Wrigglers-rhumba box, bongos). Kingston, Jamaica, 1958. [mento]

From Jamaica - Mento FA5275

14. JACK AND JILL SHUFFLE - Theophilus Beckford W/Ernest Ranglin

(Theophilus Beckford)

Theophilus Beckford-v; Roland Alphonso-ts; Emmanuel Rodriguez as Rico-tb; Ernest Ranglin-el g; Aubrey Adams-p; Cluett Johnson-b; Arkland Parks-s; Drumbago-d. Produced by Clement Seymour Dodd as Coxsone. Kingston, Jamaica, circa 1958. Coxsone (matrix #KD-45-109), Jamaica, 1960. [blues shuffle]

From Jamaica - Rhythm and Blues FA5358

15. MOSES - John Davis and the Spiritual Singers of Georgia (unknown) John Davis-lead v; Peter Davis, Bessie Jones, Henry Morrison, Willis Proctor-v. Recorded by Alan Lomax in Frederica, St. Simons Island, Georgia, April 11, 1960. Prestige/International 25002, USA, 1961. [spiritual]

From Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 Musique issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques FA5467

16. HOO-DOO BLUES - Lightnin’ Slim

(Otis Hicks aka Lightnin’ Slim)

Otis Hicks as Lightnin’ Slim-g, v; James Isaac Moore as Slim Harpo-hca. Produced by Joseph Denton Miller as Jay Miller. Crowley, Louisiana, 1960. Excello LP-8000, USA, 1960. [blues]

From Voodoo in America FA5375

17. MUSIC I FEEL [aka “Herb I Feel” and “Blue Moon”] - Count Ossie & the Wareikas

(Oswald Williams aka Count Ossie, Harry Augustus Mudie)

Oswald Williams as Count Ossie-kette repeater Ikety hand drum; The Wareikas: Emmanuel Rodriguez as Rico Rodriguez-tb; Wilton Gaynair aka Bogey as Big Bra Gaynair-ts; unknown-g; unknown maracas, other hand drum; four unknown-kette funde hand drum; unknown-bass drum. Produced by Harry Augustus Mudie. Recorded at Federal Studio, Kingston, Jamaica, circa 1961. Moodisc (no catalogue #], Jamaica, circa 1961. [nyabinghi blues]

Previously unreleased in this series.

More Count Ossie and the Wareikas music is available on:

• Jamaica - Folk Trance Possession 1939-1961 Mystic Music From Jamaica - Roots of Rastafari FA5384

• Jamaica Jazz FA5636

• Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 Musiques issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques FA5467

• Africa in America - rock, jazz, calypso FA5397

18. FREEZIN’ IN NEW-YORK - Reuben McCoy & The Hamiltonians

(Reuben McCoy)

Reuben McCoy-v, g; unknown sax, el b, perc. Produced by Quinton Edness. ZBM Radio Bermuda Studios, Hamilton, Bermuda, 1960. Bermuda BLP 408, 1960. [gombey]

From Bermuda - Gombey & Calypso FA5374

19. SINNERS WEEP - Owen Gray with Hersan & His City Slickers

(Owen Gray)

Owen Gray-v; Don Drummond-tb; Ernest Ranglin-g; Herman Sang-p; Cluett Johnson-b; Arkland Parks as Drumbago-d.

Produced by Clement Seymour Dodd aka Downbeat aka Coxsone. Federal Studio, Kingston, Jamaica, 1961. Coxsone FC 126, Jamaica, circa 1961. [soul]

From Roots of Soul FA5430. More Owen Gray music is available on Jamaica-USA Roots of Ska FA5396

20. THE ANSWER - Cecil Lloyd Group W/Tommy McCook)

(Thomas Matthew McCook aka Tommy McCook)

Billy Cooke-tp; Tommy McCook-ts; Donald Drummond as Don Drummond-tb; Ernest Ranglin-g; Cecil Lloyd Knott as Cecil Lloyd-p; Lloyd Mason-b; Lloyd Knibb-d. Produced by Clement Seymour Dodd aka Coxsone, Federal Studio, Kingston, Jamaica, 1962. Jamaica Jazz From the Workshop, Port-O-Jam PJL 01, Jamaica, 1962. [soul jazz]

From Jamaica - Jazz FA5636

21. GROOVING WITH THE BEAT - Cecil Lloyd Group

(possibly Donald Drummond aka Don Drummond)

Donald Drummond aka Don Drummond-tb; Roland Alphonso-ts; Cecil Lloyd Knott as Cecil Lloyd-p; Lloyd Mason-b; Lowell Morris-d. Kingston, Jamaica, 1958. [soul jazz]

From Jamaica - Jazz FA 5636

More Cecil Lloyd Group music is available on Jamaica - Jazz FA5636

22. IMPRESSION - Joe Harriott Quintet

(Joseph Arthurlin Harriott aka Joe Harriott)

Ellsworth McGranahan Keane as Shake Keane-tp; Joseph Arthurlin Harriott as Joe Harriott-as; Pat Smythe-p; Coleridge Goode-b; Philip William Seamen as Phil Seamen-d. Produced by Dennis Preston, Lansdowne Studios, London, November 1960. Free Form, Jazzland JLP 49, UK, 1961. [free jazz]

From Jamaica - Jazz FA5636

23. CREOLE O VOUDOUN (Yanvalou)

(traditional)

Unknown-v, drums; Recorded by Eleanora Derenkowskaia as Maya Deren. Haiti, possibly Port-au-Prince, 1953. Production supervisor-Jac Holzman. Voices of Haiti, Elektra EKLP5, New York, USA, 1953. [voodoo ritual]

From Haiti - Vodou - Folk Trance Possession, Ritual Music From the First Black Republic FA5626

24. DO YOU STILL LOVE ME? - Bob Marley

(Robert Nesta Marley aka Bob Marley)

Robert Nesta Marley as Robert Marley-v; Beverley’s All Stars: Jerome Haines as Jah Jerry-g; unknown-p; unknown-el p; Roland Alphonso-ts; Charlie Organaire-harmonica; Lloyd Brevett-b; Arkland Parks as Drumbago-d; recording engineer-Buddy Davidson. Produced by Leslie Kong, Federal Studio, Kingston, Jamaica, circa February, 1962. Beverley’s LM 027, Jamaica, 1962. [blues shuffle]

Previously unreleased in this series.

B-side of Bob Marley’s very first single. The A-side can be found on Jamaica-USA - Roots of Ska FA5396

Disc 2

1. NEGRO MI CHA-CHA-CHÁ - Facundo Rivero y su Quarteto

(Facundo Rivero )

Elba Montalvo-lead v; Carmita Lastra, Abelardo “Ebano” Rivero as Ebano Rivero, Jesus Leyte-v; Facundo Rivero-p, leader; b, perc, congas. RCA LPM 1081, USA, 1955. [cha-cha-chá]

More cha-cha-chá music is available on Anthologie des musiques de danse du monde vol. 2, disc 6 Cha-Cha-Chá FA5342

2. GOZA MI TRUMPETA - Israel «Cachao» López y Su Ritmo Caliente

(Osvaldo Estivill)

Cachao y su Combo

Vocalists vary on different tracks and include: Alfredo León, Adelso Paz Rodriguez aka Rolito, Orlando Reyes, Estanislao Laíto Sureda Hernandez aka Laíto Sureda aka Laíto Sr., Pachungo Fernández, Memo Furé, Gerardo Portillo-v; Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Richard Egües-fl; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-music direction, b; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines-congas; Guillermo Barreto-timbales; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo-bongos; Gustavo Tamayo-güiro. La Havana, 1957. Album Descargas Cubanas, Panart LD-2092, Cuba, 1957. [descarga]

From Cuba Jazz - Jam Sessions, Descargas FA5722

3. IT AIN’T NECESSARILY SO - Cal Tjader

(George Gerschwin)

Callen Radcliffe Tjader, Jr. as Cal Tjader-vibraphone; Al Porcino, Charlie Walp, Richard Harrison Collins aka Dick Collins, John Howell-tp; Manuel Duran-p; Carlos Duran-b; Edgar Rosales-congas or cowbell; Bayardo Velardi-congas or cowbell. Los Angeles, 1956. Fantasy 3221, USA, 1956. [rumba]

From Cuba in America FA5648

4. MI SONCITO - Celia Cruz y la Sonora Matancera

(Isabel Valdés) [aka “My Tune”]

Celia Cruz-lead v; Conjunto La Sonora Matancera: possibly Calixto Leicea-tp; Pedro Knight-tp; Ezequiel Frías aka Lino-p; Carlos Pablo Vázquez Gobín aka Bubú-string b; Nelson Pinedo-background v; Carlos Manuel Diaz Alonso aka Caíto-maracas, background v; Rogelio Martínez Díaz-g, background v, leader; Angel Alfonso Furias aka Yiyo-congas. Havana, 1955. Seeco 7586, Cuba, 1955. [son montuno]

From Cuba - Son FA5752

5. TAMBORES AFRICANOS - Celina y Reutilio y su Conjunto Típico

Celina González-v; Reutilio Domínguez-v, g; unknown-mandolin, b, maracas, bongos, congas. Havana, Cuba, 1956. Suaritos LP-S-103, 1956. [punto/guaguancó, ode to Santa Barbara]

Previously unreleased in this series.

More Celina y Reutilio y su Conjunto Típico music is available on Cuba - Santería FA5791

6. AY LOLA - Chiquitin Garcia y su Trio

(De Jesus)

José Juan Garcia aka Chiquitín-v, g; Gil Colon-v, g; Heri-v; b, bell, timbales, perc. Puerto Rico, circa 1957. Surprise Partie sud américaine Vol. 1 Seeco-Vogue LD.375-30, France, 1958. [plena]

From Puerto Rico - Plena, Bomba, Mambo, Guaracha, Pachanga, to be issued by Frémeaux & Associés in 2022

7. Las batatas - Dioris Valladares y su Conjunto Tipico

(Efrain Rivera aka Mon Rivera)

Isidro Valladares aka Dioris Valladares-v; possibly Tavito Vásquez-as; unknown acc., ts, tambora, güira. Produced by Rafael Pérez Dávila. New York City, circa 1956. Ansonia ALP-1203, USA. [merengue]

From Dominican Republic - Merengue FA5450

8. MONTUNO GUAJIRO- Niño Rivera’s Cuban All Stars

(Andrés Perfecto Eleuterio Goldino Confesor Echevarría Callava aka Niño Rivera)

Niño Rivera’s Cuban All-Stars: unknown v, chorus; Alejandro Vivar aka El Negro-tp; Richard Egües-fl; Emilio Peñalver-ts; Andrés Perfecto Eleuterio Goldino Confesor Echevarría Callava aka Niño Rivera-tres, conductor; Orestes López Valdés aka Orestes López as Macho-p; Salvador Vivar as Bol Vivar-b; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo as Yeyito-bongos; Tata Güines-congas; Gustavo Tamayo- guiro; Guillermo Barreto-timbales. Havana, 1957. Panart LP-3090, USA, 1962. [descarga]

From Cuba Jazz - Jam Sessions, Descargas FA 5722

9. SAN LUISERA ‐ Grupo Compay Segundo

(Manuel Proveda)

Francisco Repilado aka Compay Segundo‐armónico [seven string g], v; Amparo Repilado‐v; g; string b; guira; bongos, congas. Panart 45, 1957. Havana, circa 1957 [son].

From Cuba - Son FA 5752

10. LA BOTIJUELA DE JUAN - Conjunto Sones de Oriente

(Martin Valiente)

Concepción López Serrano, Pablo Correa, Francisco Corrales y Martin Valiente‐v; Pablo Correa‐leader; Orchestra. Havana, circa 1962. Areito LDA‐3371, Cuba, circa 1962. [son]

From Puerto Rico - Plena, Bomba, Mambo, Guaracha, Pachanga, to be issued by Frémeaux & Associés in 2022

11. CONTRE DANSE N°4 – Nemours Jean-Baptiste

(Nemours Jean-Baptiste)

Julien Paul-v; Nemours Jean-Baptiste-arr., leader, ts; Richard Duroseau-acc; b, graj scrape percussion, congas. Produced by Joe Anson, Port-au-Prince circa 1958. [contredanse/quadrille]

From Haiti - Merengue & Konpa FA5615

12. MIN CIG OU - Nemours Jean-Baptiste

(Nemours Jean-Baptiste)

Louis Lahens-v; Jean-Claude Félix-v; Nemours Jean-Baptiste-ts, arr., leader; as; tp; tb; Raymond Gaspard-g; Richard Duro- seau-acc; b; tachatcha scrape percussion; congas. Produced by Joe Anson, Port-au-Prince, 1961. The Sensation of the Day, Ibo ILP 107, 1961. [konpa]

From Haiti - Merengue & Konpa FA5615

13. EL MARINERO - Damíron y Chapuseaux

(Ricardo Rico)

José Ernesto Chapuseaux aka El Negrito Chapuseaux-v; Francisco Alberto Simó Damirón-p; unknown tp, as, ts, other horns, tambora, güira, chorus. Produced by Sidney Siegel. Seeco SCCD-9260, circa 1962.

[merengue]

From Dominican Republic - Merengue FA5450

14. LA PESADILLA - Luis Quintero y Su Conjunto Alma Cibaeña

(Emilio Nuñez)

Milito Perez-v; possibly Tavito Vásquez-as; unknown acc., ts, b, güira, chorus; Luis Quintero-tambora, leader. Produced by Rafael Pérez Dávila. New York, 1962. Merengues Vol. 4 Ansonia SALP 1327. [merengue carabinier]

From Dominican Republic - Merengue FA5450

15. MAMBO DE CUCO - Mongo Santamaría y La Playa Sextet

(Nicholas Martinez)

Rudi Calzado-v; Bayardo Velarde, Pete Escovedo-v; Louis Valizan, Marcus Cabuto-tp; Rolando Lozano- ; Felix Legarreta aka Pupi or José Silva aka Chombo-vl. Victor Venegas-b; René Hernandez aka El Flaco-p; Willie Bobo-timbales; Mongo Santamaría-congas, leader. Fantasy 3314. New York, circa 1959. [mambo]

From Cuba in America FA5648

16. CONMIGO - Eddie Palmieri y su Conjunto “La Perfecta”

(Eduardo Palmieri aka Eddie Palmieri)

Eduardo Palmieri as Eddie Palmieri-p, leader; George Castro-fl; Barry Rogers, João Donato-tb; Willie Matos, Joe DeMare, Harold Wegbreit, Dave Tucker, Al DiRisi-tp; Joe Rivera-b; Mike Collazo, Chickie Pérez, Charlie Palmieri, Manny Oquendo, George Maysonet-perc; Chivirico Dávila, Willie Torres, Víctor Velásquez-chorus. New York, 1962. Alegre LPA 817, USA, 1962. [pachanga]

From Puerto Rico - Plena, Bomba, Mambo, Guaracha, Pachanga, to be issued by Frémeaux & Associés in 2022

17. WOLENCHE FOR CHANGÓ - Mongo Santamaría

(Ramón Santamaría aka Mongo Santamaría)

Lead v, vocal chorus may include: Alfredo León, Adelso Paz Rodriguez aka Rolito, Orlando Reyes, Estanislao Laíto Sureda Hernandez aka Laíto Sureda aka Laíto Sr., Pachungo Fernández, Memo Furé, Gerardo Portillo. Possibly: Niño Rivera-tres; Israel López Valdés aka Cachao-b, dir.; Federico Arístides Soto Alejo aka Tata Güines or Ricardo Abreu aka Los Papines-cg; Guillermo Barreto-timb; Rogelio Iglesias aka Yeyo-bongos; Gustavo Tamayo-güiro. Havana, circa 1960. Fantasy F-8045, USA, 1960. [santería]

From Cuba - Santería FA5791

18. ORIZA - Cortijo y su Combo

(José Silvestre Méndez López aka Silvestre Méndez)

Ismael Rivera-v; band members may include: Sammy Ayala-güiro, v; Héctor Santos-ts, Rogelio Velez as Kito Velez-tp; Rafael Ithier Nadal aka Rafael Ithier-p; Rafael Antonio Cortijo Verdejo as Rafael Cortijo-timbales, bell, perc.; Martín Quiñones-congas; Miguel Cruz-b; Roberto Roena-perc.; vocal chorus. San Juan, 1962. Gema LPG-1186 (1962). [bomba ganga]

From Puerto Rico - Plena, Bomba, Mambo, Guaracha, Pachanga, to be issued by Frémeaux & Associés in 2022

19. ZOMBIE JAMBOREE - Lord Jellicoe and His Calypso Monarchs

(Winston O’Conner aka Lord Intruder)

Jellicoe Barker as Lord Jellicoe-lead v; Oscar Bainbridge-conga; Harold Williams-g, v; Alfred Williams-b; “Pee Wee” Bailey-maracas, v. Produced by Edward Seaga and Byron Lee, Federal Studio, Kingston, Jamaica. Sunny Jamaica, WIRL L/P 1910, Jamaica, 1962. [mento]

Previously unreleased in this series.

More mento music is available on Jamaica - Mento FA 5275

20. MAGDALENA - L’Orchestre Dels’ Jazz Biguine

(Eugène Delouche)

Eugène Delouche-cl, leader; Claude Martial-g; Gérard Lockel-2nd g; Roger Hubert-tp; Bill Temper, Pierre Rassin-tb; Luis Fuentes-fl; Claude Martial-p; José Riestra-b; Bruno Sylva Martial-d. Early November, 1951. Ritmo, 1951 or 1952. [creole waltz]

From Del’s Jazz Biguine FA 5352

21. JE PEUX PAS TRAVAILLER - Henri Salvador et sa guitare, avec orchestre & chœurs

(Boris Vian, Henri Salvador)

Henri Gabriel Salvador as Henri Salvador-v; unknown g; b, maracas, congas, bongos. Paris, February 1958

E.p. Barclay 70139, 1958. [biguine]

From Henri Salvador - Intégrale - Volume 4 FA5464

22. MON AUTOMOBILE - Robert Mavounzy et L’Orchestre Traditionnel de la Guadeloupe

(unknown)

Orchestre Traditionnel de la Guadeloupe : Robert Mavounzy-v, cl; Alain Jean Marie-p; Donnadié Monpierre-b; Ursule Théomsi as Théomel-d; Charly Chomereau-Lamotte-congas. Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, fin 1966. Aux Ondes - LRC 01, 1967. [biguine]

From L’Album D’Or de la Biguine FA5259

23. PASTOURELLE - Ambroise Gouala et l’Ensemble de Quadrille Guadeloupéen

(unknown)

Ambroise Gouala-v (commandeur); Élie Cologer-v; Donnadié Monpierre-b; unknown-g, perc. Produced by Raymond Célini. Pointe-à- Pitre, Guadeloupe, 1972. [quadrille]

From L’Album D’Or de la Biguine FA5259

24. SOULAGE DO A KATALINA

(traditional)

Philippe Yéyé aka Thomas Bailiff-v; Guy Rospor-maké drum; Alain Régent-boula drum. Recorded by Claudie Marcel-Dubois and Marguerite Pichonnet-Andral for the MNATP (Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires, now MuCEM), Saint-Claude, Guadeloupe, 1971. [gwoka]

From France d’Outremer FA5269