- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

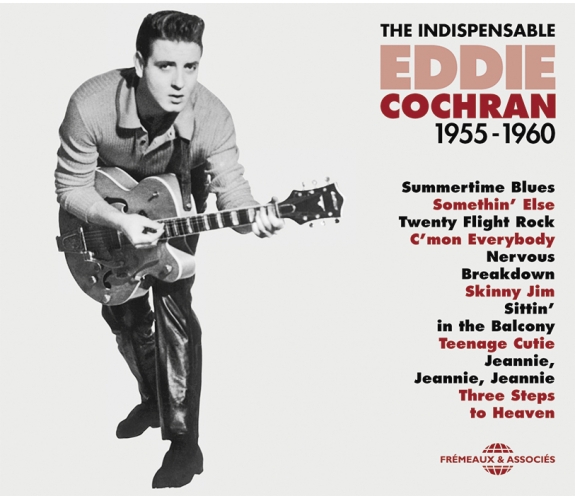

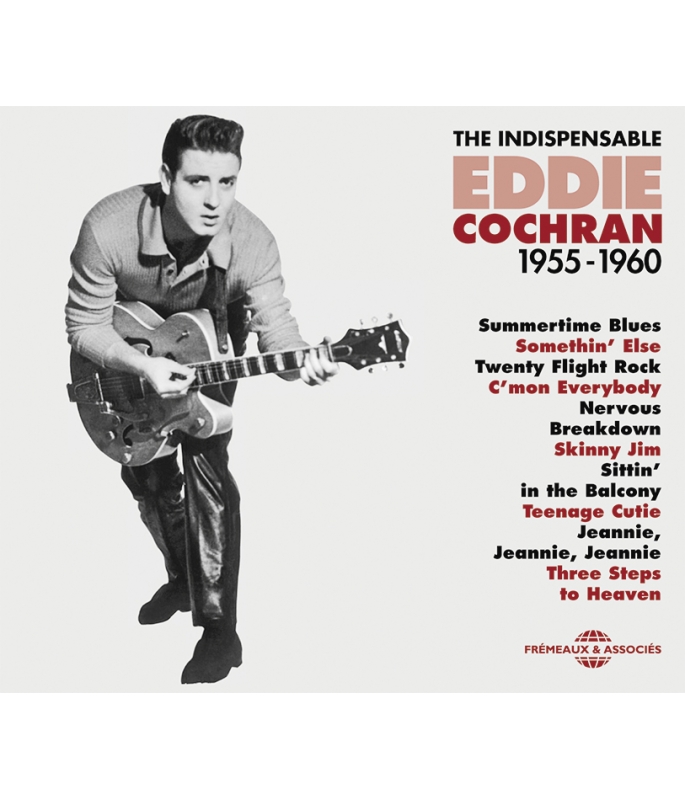

EDDIE COCHRAN

Ref.: FA5425

EAN : 3561302542522

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 31 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

Dead at 21 in an accident after a few records which came like flashes, the creator of Three Steps to Heaven, Twenty Flight Rock, C’mon Every body, Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie, Somethin’ Else and Summertime Blues remains of one rock’s greatest legends. A brilliant and sober guitarist, he was also an entertainer who had irresistible charm. Eddie Cochran’s original style epitomized the best sounds of late Fifties’ America; he substantially influenced the pop music of the Sixties and beyond. In this definitive 3CD set Bruno Blum details the brief career of this incredibly gifted figure. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Mr FiddleEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:261955

-

2Two Blue Singin StarsEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:391955

-

3Pink Peg SlacksEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:01:551956

-

4Yesterday's HeartbreakEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:051956

-

5My Love To RememberEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:041956

-

6Tired And SleepyEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:061956

-

7Fool's ParadiseEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:101956

-

8Slow DownEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:031956

-

9Open The DoorEddie Cochran - The Cochran BrothersEddie Cochran00:02:081956

-

10Long Tall SallyEddie CochranRichard Blackwell00:01:471956

-

11Blue Suede ShoesEddie CochranCarl Perkins00:01:511956

-

12I Almost Lost My MindEddie CochranIvory Joe Hunter00:02:311956

-

13That's My DesireEddie CochranHelmy Kresa00:02:081956

-

14Twenty Flight RockEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:461956

-

15Dark Lonely StreetEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:241956

-

16Ping Peg SlacksEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:111956

-

17Half LovedEddie CochranRay Stanley00:02:291956

-

18Skinny JimEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:151956

-

19Cotton PickerEddie CochranWortham Watts00:02:151956

-

20Sittin In The BalconyEddie Cochran00:02:021957

-

21Sweetie PieEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:111957

-

22Mean When I'M MadEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:551957

-

23One KissEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:501957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Teenage CutieEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:371957

-

2Drive In ShowEddie CochranFred Dexter00:02:031957

-

3Am I BlueEddie CochranH. Akst00:02:181957

-

4Completly SweetEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:221957

-

5Undying LoveEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:091957

-

6I'M Alone Because I Love YouEddie CochranIra Schuster00:02:231957

-

7Loving TimeEddie CochranJan Woolsey00:02:071957

-

8Proud Of YouEddie CochranJay Fitzsimmons00:02:001957

-

9Stockings And ShoesEddie CochranLyle Gaston00:02:191957

-

10Tell Me WhyEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:181957

-

11Have I Told You Lately That I Love YouEddie CochranScott Greene Wiseman00:02:361957

-

12Cradle BabyEddie CochranTerry Fell00:01:501957

-

13Twenty Flight RockEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:451957

-

14A Pocketful Of HeartsEddie CochranFred Dexter00:01:571957

-

15NeverEddie CochranTerry Fell00:01:531957

-

16Pretty GirlEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:521958

-

17Jeannie Jeannie JeannieEddie CochranGeorge Motola00:02:231958

-

18Little LouEddie CochranEddy Daniels00:01:421958

-

19Summertime BluesEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:011958

-

20TeresaEddie CochranGary Carmody00:02:081958

-

21Don't Ever Let Me GoEddie CochranJay Fitzsimmons00:02:131958

-

22Let's Go TogetherEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:581958

-

23Teenage HeavenEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:101959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1C'Mon EverybodyEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:581958

-

2Nervous BreakdownEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:211958

-

3I RememberEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:181959

-

4My WayEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:171959

-

5Rock'N Roll BluesEddie CochranBede Korstein00:02:231959

-

6Three StarsEddie CochranTom Donaldson00:03:401959

-

7Week EndEddie CochranBill Post00:01:521959

-

8Think Of MeEddie CochranK. Sheeley Sharon00:02:001959

-

9Three Steps To HeavenEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:251959

-

10Somethin' ElseEddie CochranK. Sheeley Sharon00:02:061959

-

11Boll Weelin' SongEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:591959

-

12Little AngelEddie CochranAlbert Winn00:01:521959

-

13My Love To RememberEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:581959

-

14Jelly BeanEddie CochranMaurice Maccall00:02:041959

-

15Don't Bye Bye MeEddie CochranMaurice Maccall00:02:171959

-

16Hallelujah I Love Her SoEddie CochranRay Charles00:02:201959

-

17Cut Across ShortyEddie CochranMarjorie Wilkin00:01:511959

-

18Fourth Man ThemeEddie CochranJerry Capehart00:02:041959

-

19Milk Cow BluesEddie CochranJames Arnold00:03:121959

-

20Eddie's BluesEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:04:001959

-

21Strollin' GuitarEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:551960

-

22Country JamEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:02:011959

-

23Hammy BluesEddie CochranEddie Cochran00:01:441959

-

24Cherished MemoriesEddie CochranK. Sheeley Sharon00:01:531959

FA5425 Eddie COCHRAN

THE INDISPENSABLE

EDDIE COCHRAN

1955-1960

Décédé dans un accident à 21 ans après quelques disques fulgurants, le créateur de Three Steps to Heaven, Twenty Flight Rock, C’mon Every-body, Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie, Somethin’ Else et Summertime Blues reste l’une des grandes légendes du rock. Brillant, sobre guitariste et chanteur au charme irrésistible, son style original est un concentré du meilleur son américain de la fin des années 1950. Eddie Cochran a considérablement influencé la musique populaire des années 60 — et bien au-delà. Bruno Blum raconte, dans ce coffret triple CD, la carrière éclair de ce surdoué.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Dead at 21 in an accident after a few records which came like flashes, the creator of Three Steps to Heaven, Twenty Flight Rock, C’mon Every-body, Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie, Somethin’ Else and Summertime Blues remains of one rock’s greatest legends. A brilliant and sober guitarist, he was also an entertainer who had irresistible charm. Eddie Cochran’s original style epitomized the best sounds of late Fifties’ America ; he substantially influenced the pop music of the Sixties and beyond. In this definitive 3CD set Bruno Blum details the brief career of this incredibly gifted figure.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

Eddie Cochran

The Indispensable 1955-1960

Par Bruno Blum

Eddie Cochran ? Il est… [il montre sa guitare Gretsch, la même que Cochran, et sa coiffure] Il est tout ! Il est mon meilleur pote. Le type qui m’a le plus influencé c’est Eddie Cochran. Au début c’était cette pochette de disque où il est debout comme ça [il prend la guitare comme une mitrailleuse] et ses pantalons amples. Je me suis dit oh, ce type a l’air vraiment cool et je veux lui ressembler à fond. Et puis je me suis payé l’album, je l’ai apporté chez moi et il m’a soufflé. Somethin’ Else c’était comme un hymne, « Elle est vraiment tellement jolie, mec, elle n’a rien à voir ». C’était ça. C’était le meilleur.

— Brian Setzer, 19831.

Ray Edward Cochrane (3 octobre 1938-17 avril 1960) dit Eddie Cochran est né dans le Minnesota à Albert Lea, une petite ville agricole prospère située tout au nord de l’Amérique rurale profonde. À une journée de route au nord ouest de Chicago, les chaleurs y étaient étouffantes en été et les températures quasi polaires en hiver. C’est pendant la grande crise économique des années 1930 que les parents d’Eddie avait été contraints de déménager si loin au nord de leur ville natale d’Oklahoma City, où Frank travaillait en usine. Cette dramatique période de récession avait été aggravée par des sécheresses, tempêtes et invasions d’insectes à répétition qui ont meurtri tout le sud du pays et poussé les paysans ruinés à affluer vers le nord et la Californie. Heureusement, Frank était parvenu à décrocher un job d’agent d’entretien (ménages) à Albert Lea, où avec son épouse Alice il éleva Gloria, Bill, Bob, Patty et le petit dernier Eddie, plus jeune de six ans. Le grand frère Bill possédait une guitare Kay, puis une Martin, mais Eddie n’y touchait pas souvent. Il voulut d’abord jouer de la batterie, puis du trombone. Son autre frère, Bob, s’intéressera sérieusement à la musique et composera plus tard avec Eddie Hammy Blues et les classiques Three Steps to Heaven et Somethin’ Else.

Frank Cochrane deviendra mécanicien en 1946. Déracinée, la famille était très attachée à l’Oklahoma où elle avait grandi. Comme d’autres musiciens du Minnesota Bob Dylan et Prince (dont les quatre grand-parents étaient originaires de Louisiane), Eddie Cochran plongeait ses influences musicales dans le sud des États-Unis. En 1951 Eddie avait treize ans quand la famille Cochrane déménagea à Los Angeles, où s’était déjà installé Bill l’aîné. Mais Eddie continuera toujours à revendiquer l’identité de sa famille Okie alors qu’il n’avait jamais mis les pieds dans l’Oklahoma. Il la chantera même en juin 1959 sur Boll Weevil, une chanson traditionnelle faisant allusion aux charançons (l’anthonome du cotonnier) qui ont dévasté les plantations de coton du sud avant-guerre :

Si on vous demande/Qui vous a chanté cette chanson/Dites que c’est un guitariste d’Oklahoma City/Qui portait des blue jeans/Et cherchait son chez lui

— Eddie Cochran, Boll Weevil, Juin 1959

Le terme « boll weevil » était aussi employé pour désigner certains élus du parti Démocrate (la gauche américaine) du sud qui soutenaient des idées très à droite et la ségrégation raciale en particulier. Pour ceux qui n’appréciaient pas leurs opinions racistes, ces boll weevils n’étaient qu’une engeance, une maladie très répandue, des traîtres à la cause modérée. Leurs positions de droite mèneront plus d’un boll weevil à rejoindre l’opposition, les Républicains menés par le président Eisenhower, un militaire conservateur au pouvoir (de 1953 à 1961, avec Richard Nixon comme vice-président) pendant toute la carrière d’Eddie Cochran. Bien décidé à réussir, Eddie chantera sur Cotton Picker qu’on ne fera pas de lui un « ramasseur de coton », une plante très cultivée dans l’Oklahoma.

Strollin’ Guitar

En 1951 Frank trouva un job dans une usine de missiles de Los Angeles. À treize ans son fils Eddie était déjà passionné par sa guitare sèche, qu’il ne lâchait pas d’un millimètre. Brutalement coupé de tous ses amis lors du déménagement dans le modeste quartier de Bell Gardens (5539 Priory Street), son instrument devint son meilleur ami. C’est au lycée Bell Gardens Junior High School à l’est de Los Angeles qu’à l’âge de quinze ans Eddie rencontra Conrad Smith, dit Connie, le contrebassiste de l’orchestre de l’école. Connie jouait aussi de la steel guitar et de la mandoline et partagea sa passion musicale avec son nouvel ami. Fin 1953, ils formèrent un trio avec un copain d’école à la guitare solo et Connie à la basse. Eddie était à la rythmique. Ils répétaient dans l’arrière-boutique du Bell Garden Music Centre, un magasin de musique dont le propriétaire Bert Keither avait remarqué les talents d’Eddie et encourageait les adolescents. Il leur trouva leurs premiers engagements (soirées à l’école, ouverture de supermarché, etc.), de précieuses expériences. L’année suivante Eddie Cochran se consacra beaucoup à la musique dans son quartier, un bastion du rhythm and blues et de la country où vivaient nombre de musiciens qu’il fréquentait avec application. Il absorba diverses influences et rêvait déjà d’une carrière de professionnel. Marqué très tôt par la difficile technique « fingerpicking » de Chet Atkins qu’il essayait de maîtriser (comme Scotty Moore, le guitariste d’Elvis — et littéralement tous les guitaristes de country music), le jeune Eddie travaillait beaucoup son instrument. On peut l’écouter ici faire une démonstration de picking sur Country Jam, un instrumental dans le style bluegrass très particulier. Ses mains fines et de petite taille étaient souples, capables de couvrir une grande surface du manche. Il apprenait les difficiles parties country de Joe Maphis2, les techniques de thumbpick (onglet du pouce), flat pick (médiator) et finger picking (plusieurs doigts, avec ou sans médiator) et assimila le jazz (Johnny Smith, Jimmy Wyble). Tous les témoignages confirment qu’Eddie était très curieux, ouvert, intelligent et qu’il apprenait très vite. Son adaptation de « The Third Man Theme » du viennois Anton Karas devint Fourth Man Theme et montre la diversité de ses goûts. On trouve ici d’autres exemples de son éclectisme, avec des influences allant du bluegrass à la country et du blues au rock. Les rocks instrumentaux à la guitare étaient à la mode depuis « The Hucklebuck » de Earl Hooker (1953) et le « Honky Tonk » de Bill Doggett en 1956 ; influencé par le succès de Duane Eddy et son nouveau style de guitare « twang » Gretsch (« Rebel Rouser », 1958) Cochran expérimentera dans cette veine instrumentale (fin du disque 3), notamment avec Strollin’ Guitar, caractéristique de ce genre à part objet d’une anthologie dans cette collection3.

The Cochran Brothers

C’est en octobre 1954 qu’Eddie fut présenté à un certain Hank Cochran, un orphelin de son quartier au parcours ingrat, un prolétaire récemment passé musicien semi-professionnel. Hank proposa vite à Eddie de l’accompagner en tant que soliste et choriste. Les duos de frères étaient à la mode dans la musique country (McGee Brothers, Stanley Brothers, Monroe Brothers, Collins Kids, Louvin Brothers, Blue Sky Boys et bientôt les Everly Brothers…).

Les deux copains portaient presque le même patronyme et décidèrent de se produire sous le nom des Cochran Brothers. À seize ans et quatre mois en janvier 1955, Eddie interrompit donc définitivement sa scolarité pour accompagner Hank Cochran, un chanteur et guitariste rythmique décidé. Après quelques répétitions ils tournèrent en Californie mais le jeune âge d’Eddie leur interdisait de jouer dans les lieux vendant de l’alcool, ce qui limita le nombre de leurs prestations.

En 1955 Eddie fit l’acquisition du nouveau modèle de guitare Gretsch électrique, la demi-caisse 6120 vendue au prix de 385 dollars au Bell Garden Music Centre. Sa 6120 était équipée d’un système de bras trémolo Bigsby qui lui permettait des effets nouveaux (écouter Eddie’s Blues au style d’une grande originalité) jusque-là surtout utilisés par Chet Atkins, lui aussi adepte du son Gretsch. Eddie la modifia, notamment en remplaçant le micro grave par un P-90 Gibson.

C’est aussi au Bell Gardens Music Centre où traînaient les musiciens du quartier que Bert Keither présenta Jerry Capehart à Eddie. Fils d’un fermier ruiné dans les années 1930 et émigré en Ford T en Californie, Capehart appréciait la country music et jouait du violon dans un groupe semi-professionnel. Il avait été appelé pendant la guerre de Corée, et trop pauvre pour réaliser son ambition de juriste, depuis 1953 il travaillait la nuit dans une usine d’avions. Auteur compositeur à la piètre voix, il cherchait des musiciens capables de chanter et enregistrer ses morceaux. Les Cochran Brothers acceptèrent d’en interpréter quelques-unes pour l’enregistrement d’un disque de démonstration.

En avril 55 les deux faux frères furent engagés par Steve Stebbins (American Music Corporation), le principal agent de country music en Californie (Merle Travis, Tennessee Ernie Ford) qui allait bouleverser leur carrière. Stebbins organisa aussitôt leur promotion. Ils furent invités à jouer dans l’importante émission de télévision Home Town Jamboree de son associé Cliffe Stone, à la radio (populaire émission Town Hall Party) et présentés à Red Matthews de la petite marque de disques indépendante Ekko. Leurs premiers enregistrements très marqués par le style plaintif d’Hank Williams Mr. Fiddle et Two Blue Singin’ Stars (un hommage à Jimmie Rodgers et Hank Williams), où l’on peut entendre la voix d’Eddie et sa guitare très country, ouvrent cet album. Leur premier 45 tours est sorti pendant l’été, occasionnant un concert au Big D Jamboree de Dallas diffusé sur la populaire radio locale KLRD.

Ils y avaient été précédés quelques jours plus tôt par Elvis Presley, dont le nouveau style mélangeant country et rhythm and blues avait fait très forte impression sur le public country jusque-là plutôt pépère. Elvis était déjà un phénomène avec son cortège d’évanouissements, de hurlements, de sécurité débordée et de musique fraîche et excitante qui contrastait avec la country conventionnelle. Les deux Cochran prirent alors conscience de la popularité du rockabilly, un nouveau style de rock qui ajoutait une guitare aux racines country sur le rhythm and blues afro-américain. Le rock était jusqu’alors peu connu du grand public blanc. Pauvres, sans grand succès, les Cochran voyageaient dans des conditions difficiles et durent rentrer en stop d’un voyage à Memphis où ils voulaient voir les bureaux d’Exxo. De retour à L.A. ils accompagnèrent aussi Jerry Capehart pour un 45 tours assez quelconque, enregistré avec des musiciens noirs (production de John Dolphin pour Cash Records). En janvier 1956 ils partirent en tournée sur toute la côte ouest, jusque dans l’état de Washington. Invités régulièrement à la télévision KORV en Californie, ils accompagnèrent aussi Jack Wayne, un DJ de la radio KVSM qui copiait Johnny Cash, et d’autres artistes country. Leurs disques étaient publiés sans aucun succès. Les invitations à la télévision ont augmenté leur notoriété et Jerry Capehart, de plus en plus actif, chanta avec eux sur scène en mars. Il organisa aussi d’autres séances d’accompagnement pour des artistes de hillbilly qu’il présenta à Dolphin, et devint de fait le manager des Cochran Brothers. Capehart avait un bon contact avec leur agent American Music, une société importante qui avait créé les disques Crest afin d’exploiter ses nombreux talents qu’elle mettait sur la route — et dont elle éditait les chansons en échange d’une avantageuse partie des droits d’auteur. Mais enraciné dans la country de papa, avec son gros catalogue de classiques hillbilly (Merle Travis, Roy Rogers, Delmore Brothers, etc.) American Music était de plus en plus dépassé par les innovations du rock, qui prenait son envol dans le grand public.

Rockabilly

En 1956 après dix-huit mois de succès avec la petite marque Sun, les disques RCA ont racheté et massivement lancé Elvis Presley. Le succès foudroyant de son premier 45 tours pour RCA « Heartbreak Hotel » bouleversa l’industrie du disque en janvier 19564. Depuis plusieurs mois, cet artiste blanc interprétait avec grand succès des chansons de rock, un style jusque-là réservé aux afro-américains. Nombre d’entre elles étaient composées par des artistes noirs/métis. Son producteur initial Sam Phillips lui avait adjoint Scotty Moore, un guitariste de hillbilly, le style emblématique des Blancs du sud. Mélange de rhythm and blues et de hillbilly, ce nouveau style de rock ‘n’ roll s’appelait le rockabilly. Comme Eddie, Scotty Moore était très influencé par Chet Atkins5 et donnait une couleur « blanche » à des reprises comme le Milk Cow Blues de Kokomo Arnold (la version d’Eddie Cochran incluse ici était inspirée par celle d’Elvis). Le succès hors de toute proportion d’Elvis Presley a fait connaître le rock au grand public blanc. Excitant, libérateur, incitant à la danse libre, le rock était plébiscité par le public noir depuis longtemps sous le nom de jump blues, rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm and blues, des termes racialement connotés. Et dans une Amérique où la ségrégation raciale était instituée depuis des siècles, dès 1955 des artistes afro-américains comme Ray Charles6, Bo Diddley7, Little Richard8 et Chuck Berry9 commençaient à percer auprès du grand public blanc en dépit de leur couleur. Le rock ‘n’ roll dérangeait l’Amérique conservatrice mais avec ses petits groupes faciles à transporter, il rapportait gros. Les compositions afro-américaines qui avaient fait leurs preuves étaient souvent inconnues du public blanc, et de nouvelles versions par des artistes blancs étaient garanties de vendre. Naturellement les concurrents de RCA cherchaient activement des artistes de rock blancs capables de rivaliser avec le phénomène Elvis Presley, qui était confirmé par le succès du pionnier Bill Haley10 and his Comets et leur hymne « Rock Around the Clock ». C’est pile à ce moment-là que Jerry Capehart a placé une de ses chansons à Jack Lewis, dont les enregistrements étaient financés par les deux découvreurs de talent des disques Crest, Ray Stanley et Dale Fitzsimmons. La version de Jack Lewis n’aura aucun succès mais la composition de Capehart provenait de la bande de démonstration convaincante enregistrée par les Cochran Brothers. Les deux acolytes de chez Crest n’ont pas mis longtemps à comprendre qu’Eddie Cochran valait de l’or. Ils ont organisé une séance d’enregistrement des Cochran Brothers où Eddie pourrait tenter sa chance seul au micro.

C’est sous le nom du duo qu’Eddie enregistra à dix-sept ans son premier titre fulgurant, un rockabilly d’anthologie où il chante seul à la guitare, accompagné par son ami contrebassiste et une lointaine percussion. Basé sur le même thème vestimentaire que Blue Suede Shoes, un rockabilly de Carl Perkins qu’Eddie gravera lui-même un mois plus tard, Pink-Peg Slacks raconte son désir irrépressible d’un ample pantalon rose à pinces « zoot », rétrécissant vers le bas jusqu’à serrer la cheville. Dans la chanson il obtient la somme de sa copine, qui a demandé l’argent à son père. Selon tous les témoignages, Eddie était un grand séducteur. Son interprétation possédée indiqua aussitôt qu’il était aussi un chanteur au charisme hors-pair.

L’échec du single Tired and Sleepy/Fool’s Paradise acheva le duo Cochran Brothers. De dix ans son aîné, le dominateur Jerry Capehart et Eddie ont définitivement adopté le style rock à la mode et ont laissé tomber la country music. Marié et pas bien taillé pour le rock, après quelques essais Hank Cochran n’a pas eu envie de suivre la direction de Capehart. Lors de la séance suivante Eddie accompagna Hank Cochran à la guitare, une fin amiable pour le duo. Le seul enregistrement rock de Hank sortira sous le pseudonyme de Bo Davis11.

1956 Twenty Flight Rock

Aux âmes bien nées, la valeur n’attend point le nombre des années.

— Pierre Corneille

Dans le sillage d’Elvis surgirent des chanteurs majeurs comme Gene Vincent avec « Be-Bop-A-Lula », mais comme l’extravagant Little Richard, Gene Vincent n’était pas un soliste ; Elvis Presley avait un grand charisme, une voix d’or et dansait magnifiquement mais ne composait pas (il a tout de même signé quelques morceaux qui n’étaient pas de lui) et n’était pas un bon guitariste ; tous ces derniers avaient recours à des instrumentistes. Jerry Lee Lewis ne composait quasiment jamais ses chansons. Certes Carl Perkins composait et jouait de la guitare en soliste — mais le créateur de Blue Suede Shoes (dont la version d’Eddie figure ici) n’avait pas l’envergure de ses coreligionnaires. Le trio de Johnny Burnette trop vite séparé — aucun parmi tous ces géants du rock ne possédait la totalité des atouts du jeune homme. Déjà arrivait le rock édulcoré et commercial de Pat Boone, Ricky Nelson, Frankie Avalon, Fabian ou Paul Anka ; et si sous la pression de son producteur Eddie a enregistré plusieurs morceaux doux avec un groupe vocal rappelant fortement la formule d’Elvis Presley avec les Jordanaires (écouter le disque 2), le jeune homme a tenu une ligne rock sans compromis dès qu’on l’a laissé faire.

À dix-sept ans, le précoce Eddie Cochran était donc un artiste solo de tout premier choix. Il avait un manager et parolier ambitieux (Jerry Capehart), un agent de premier plan pour les tournées, une maison de disques et l’équipe de compositeurs d’American Music — dont Stanley et Fitzsimmons — prêts à tout pour qu’il enregistre leurs compositions dans le nouveau style rockabilly. Quoi qu’on en dise, il avait déjà tout pour lui, plus d’atouts que tous ses concurrents. Beau, intelligent, ambitieux, élégant, charmant, séduisant, chanteur irrésistible et déjà guitariste professionnel, il était en outre capable d’écrire des classiques comme Twenty Flight Rock. L’auteur compositeur interprète raconte dans cette chanson que comme l’ascenseur est en panne, il doit monter à pied. Épuisé, il ne peut pas « rock » sa chérie une fois arrivé au vingtième étage — mais ne peut pas s’empêcher de revenir encore et encore. Il était en quelque sorte le « Chuck Berry blanc » ; mais en comparaison, lors de l’enregistrement de ses premiers classiques en 1955-56 Chuck Berry avait l’expérience d’un adulte de trente ans — alors qu’Eddie en avait seulement dix-sept. Si Buddy Holly, lui aussi disparu très jeune (sa mémoire est chantée ici par Eddie sur Three Stars), a gravé nombre de morceaux remarquables pendant cette période, il n’a pas eu suffisamment de temps pour s’épanouir pleinement tandis qu’en trois ans Eddie Cochran allait graver une série de morceaux essentiels. Comme les immenses chanteurs-guitaristes Bo Diddley12 et Chuck Berry, il alliait l’originalité d’un grand interprète à des compositions de premier choix. Cet éloge pourrait continuer longtemps : il devrait aussi louer la spontanéité, la simplicité esthétique de tant d’enregistrements majeurs où ne figurent même pas une batterie, Capehart tapant des doigts sur un vieux carton.

En mai 1956 les Cochran Brothers avaient atteint le sommet de leur modeste carrière en première partie de Lefty Frizzell, une célébrité country. Ils ont ensuite travaillé les week-ends de l’été dans une boîte d’Escondido en Californie. Réputé comme guitariste dans la région, Eddie a aussi enregistré avec différents artistes country comme Wynn Stewart (« Keeper of the Keys ») et rockabilly (Skeets McDonald « You Oughta See Grandma Rock ») pour Capitol. Homme de scène et de studio déjà expérimenté, solide guitariste, capable d’interpréter des chansons romantiques comme de futurs hymnes punk, Eddie Cochran allait à l’essentiel, se démarquait de la country et avait choisi le rock. L’échec de son rockabilly Skinny Jim, sorti peu après en cet été 56, ne le découragea pas. Associé à ses créateurs afro-américains le style rock restait sulfureux. Alors que Hank Cochran et d’autres chanteurs de country enregistraient du rockabilly sous un pseudonyme de peur d’être mal perçus par le public country conservateur, Eddie enregistra les succès rock afro-américains du moment pour affirmer son appartenance au mouvement qui séduisait la jeunesse, dont Long Tall Sally de Little Richard et I Almost Lost my Mind d’Ivory Joe Hunter. Il grava aussi sa version de l’un des premiers vrais succès du rockabilly, le Blue Suede Shoes tout frais de Carl Perkins.

Capehart apporta ces nouveaux enregistrements chez Liberty, la petite marque de disques du violoniste hongrois Simon « Si » Waronker qui venait de réussir un joli coup avec le « Cry Me a River » de Julie London accompagnée par Barney Kessel. Très conservateur, Waronker avait des liens avec Lionel Newman, directeur musical des studios de cinéma Twentieth Century Fox, à qui il avait fourni des bandes de musique pour plusieurs films. Avec les Chipmunks et Henry Mancini, le choix des artistes de Liberty était tout aussi conservateur et comme à beaucoup, il manquait un chanteur de rock à leur écurie. Le phénomène Elvis Presley bouleversait toutes les conventions du métier. Capitol venait de sortir le premier disque de Gene Vincent, l’énorme succès « Be-Bop-a-Lula » et il n’y avait pas de temps à perdre. Waronker le savait et fut vite conquis par la maturité, la séduction et le talent de Cochran. Au même moment (juillet 1956), alors qu’Eddie travaillait sur l’enregistrement de la bande son d’un film à petit budget, son producteur Boris Petroff lui proposa de figurer dans son prochain film en tant que chanteur. Il demanda des chansons, ce qui donna Twenty Flight Rock, enregistré aussitôt avec Capehart tapotant sur une boîte, avec Connie Smith à la contrebasse dans un style « slap » rappelant celui de Bill Black avec Elvis Presley. Eddie y pastiche les maniérismes d’Elvis avec assurance : un classique du rockabilly était né. Il lui ouvrira la porte des studios de cinéma, et bientôt du succès. C’est aussi l’un des tout premiers morceaux que le jeune Paul McCartney apprit. Quand le 6 juillet 1957 John Lennon entendra McCartney chanter Twenty Flight Rock à la perfection à la fête de l’école, il l’engagera dans son groupe — les Beatles étaient nés13.

1957 : Singin’ to my Baby

Après d’autres perles rockabilly comme Teenage Cutie, Eddie avait dix-huit ans quand Waronker lui proposa d’enregistrer d’urgence Sittin’ in the Bal-cony, dont la version de John D. Loudermilk (sortie sous le pseudo de Johnny Dee) avait déjà du succès. Ballade sucrée, commerciale et charmante, ce premier single chez Liberty se vendra à plus d’un million d’exem-plaires. Cochran ne l’aimait pas, mais ne s’est jamais plaint de son succès. Il montera au numéro 18 en avril 1957, quatre mois après la sortie du film La Blonde et Moi (The Girl Can’t Help It, Frank Tashkin, 1956) où Eddie interprète Twenty Flight Rock, une de ses rares prestations filmées. Ce grand classique du cinéma rock a emprunté son titre à la chanson de Little Richard14 que l’on peut voir sur scène dans le film. Également au générique : Gene Vincent, les Platters15, les Treniers, Abbey Lincoln, Julie London, Fats Domino… et la vedette Jayne Mansfield.

Début 1957 Eddie Cochran joua un rôle dans un autre film, « Untamed Youth », consacré à la marginalité des jeunes rockers. Il partit ensuite en tournée à travers les États-Unis, intervenant dans les plus grandes émissions de radio, de télévision (Dick Clark Bandstand) et sur scène. C’est en avril 1957 au Mastbaum Theater de Philadephie qu’il rencontra le chanteur Gene Vincent, avec qui il devint ami.

Le succès de Sittin’ in the Balcony incita logi-quement Si Waronker à produire d’autres ballades commerciales dont on peut avoir un aperçu ici sur notre disque n°2. Le deuxième single One Kiss (mai 1957) fut un exercice auquel Eddie se plia sans enthousiasme — et ce fut un échec total. À la première occasion, les inséparables Jerry et Eddie enregistraient au petit studio Goldstar. C’est là qu’ils gravèrent leur premier album, « Singin’ to my Baby ». Waronker imposa les chœurs du groupe de Johnny Mann, et l’album entier reflète la tension entre le rockabilly nerveux, libérateur et ultra sobre dont Eddie était capable sur Am I Blue (qui ne figura pas sur l’album américain) ou Twenty Flight Rock et le son variété (I’m Alone Because I Love You) majoritaire vers lequel tirait le producteur Simon Jackson recruté par Liberty. L’album n’était donc pas représentatif du style véritable de Cochran, âgé de dix-huit ans et empêtré dans la direction artistique d’un succès qu’il ne maîtrisait pas. Sorti à la rentrée 1957 au moment où le rock était au sommet de la mode, où les classements des meilleurs ventes étaient pilonnés par des succès monstres comme « Let’s Go to the Hop » de Danny & the Juniors ou « Keep-a-Knocking » de Little Richard, le charmant single Drive-In Show n’a pas eu grand succès mais se vendit suffisamment pour qu’Eddie ne soit pas oublié par les disc jockeys.

Eddie Cochran s’habillait en tenue « sport » dans le style adopté par les sportifs des grandes écoles américaines : mocassins « loafers », pantalons larges, veste de tweed ample, cravate : des outils de séduction efficaces dans le style « teen idol », différents des attributs plus « mauvais garçon » de Gene Vincent. Une belle tournée australienne en compagnie de Little Richard et Gene Vincent a eu lieu en octobre. Accompagné par les Deejays, groupe de la vedette rock locale Johnny O’Keefe, Eddie participa à ces concerts mémorables où Little Richard déclencha des émeutes avec son jeu de scène provocant. Les adolescents démolissaient tout, arrachant les habits des artistes et faisant les titres des journaux. En tête d’affiche, Gene Vincent avait fort à faire pour rivaliser avec le créateur de Long Tall Sally, mais bien rôdé par une année de scène, il déclenchait lui aussi des scènes d’hystérie — comme Elvis le faisait quotidiennement aux États-Unis. Rompu à la scène mais moins démonstratif, Eddie Cochran eut tout de même sa part de succès, notamment auprès des adolescentes. C’est aussi en plein milieu de cette tournée légendaire que Little Richard déclara qu’il abandonnait le rock pour se consacrer à la théologie, quittant brusquement la tournée sans la terminer, ce qui fit à nouveau les titres des journaux. À peine rentré Eddie partit en tournée avec Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Paul Anka, Buddy Holly… et c’est dans les loges du Paramount à New York que Phil Everly lui présenta Sharon Sheeley, sa future élue.

De retour à Los Angeles Eddie était redevenu un musicien de studio, dirigeant des séances pour son ami Bob Bull (dit Bob Denton) pour Dot (trois singles), enregistrant nombre de maquettes pour Ray Stanley, aujourd’hui disparues pour la plupart. Une dizaine de ces morceaux de Ray Stanley avec Eddie à la guitare sont sortis chez différentes marques dont Crest et Argo. Outre ses nombreux atouts, le jeune Eddie était devenu un professionnel du studio, capable de suggérer des arrangements et de diriger des séances. Il y accompagna Lee Denson pour un obscur single paru chez Vik et Paula Morgan, Don Deal…

1958 : Summertime Blues

Les mauvaises ventes incitèrent Liberty à le laisser pour la première fois diriger ses propres séances d’enregistrement à partir de janvier 1958. Il n’était pas courant qu’un producteur se conduise de la sorte à cette époque, a fortiori un conservateur comme Waronker — sans parler du jeune âge de son protégé. Débarrassé de ce poids, Eddie put enfin donner toute sa mesure. Sans surprise, Cochran et Capehart choisirent d’enregistrer du rock : l’excellent Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie est passé près du succès, tout comme Pretty Girl enregistré quelques semaines plus tard. Les 25 et 26 mars 1958 au studio Capitol, Eddie chanta aussi des harmonies basses sur quatre titres de Gene Vincent16, dont il était devenu proche.

Mais le rock était déjà très à part du reste du show business. Cette musique avait mauvaise réputation. Infesté de chanteurs opportunistes utilisant des pseudonymes, de producteurs souvent malhonnêtes, de disc jockeys corrompus et d’arrivistes, le milieu du rock était méprisé par la plupart des professionnels en place, qui préféraient des musiques bien plus conservatrices. Les salles de concerts préféraient des artistes beaucoup plus calmes et n’accueillaient pas volontiers ce type de musique, considérée vulgaire et réservée aux adolescents mal élevés. À cela s’ajoutait un racisme généralisé : certains acceptaient mal que des Blancs soient influencés par un style caractéristique des artistes noirs dont ils enregistraient les compositions — et encore moins que des chanteurs afro-américains comme Bo Diddley ou Frankie Lymon percent dans le grand public avec ce genre jugé « inférieur ». Mais le rock rapportait gros, ce qui faisait passer la pilule et ouvrait des portes. Cependant personne ne pensait que le phénomène durerait : il fallait profiter de la mode le plus vite possible. Bombardé de critiques injustes, Elvis Presley lui-même diversifiait déjà beaucoup son répertoire — par goût personnel mais aussi par réalisme17. En 1958 la tendance était au rock édulcoré, à la variété insipide, teintée d’imageries et d’accents vaguement rock de teen idols comme Ricky Nelson, dont le succès était énorme. Secrètement amoureuse d’Eddie, la jeune Sharon Sheeley avait signé l’un des gros succès de Ricky Nelson (« Poor Little Fool ») et parvint à vendre sa balade romantique « Love Again » à Capehart, qui demanda à Eddie d’enregistrer cette chansonnette monotone. Ce qu’il fit aussitôt, profitant de l’occasion pour séduire la jeune Sharon. Ne manquait plus qu’une face B au nouveau single : basé sur le riff d’intro (jouée sur une guitare Martin), le grand classique Summertime Blues a été écrit en une heure pour figurer en face B de cette chanson très ordinaire. Sorti le 11 juin 1958, un mois après un nouvel échec (Teresa), le single écrit et produit par Cochran et Capehart est monté au numéro 8 en deux mois. Bien entendu, la face B était préférée par les DJ et elle est rapidement passée en face A. Tube de l’été bien nommé, Summertime Blues a défini le nouveau style rock créé par Eddie Cochran. Il a ensuite définitivement laissé derrière lui le rockabilly et a pu affirmer sa personnalité pour de bon avec ce nouveau son.

En septembre 1958, les disques Liberty ont créé la sous-marque Freedom consacrée au rock et donné carte blanche à Jerry Capehart, imprésario d’Eddie Cochran, John Ashley et de l’excellent Johnny Burnette and his Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio18. Après 26 singles pour la plupart médiocres (Capehart devait fournir un quota de productions) auxquels Eddie a participé en tant qu’arrangeur et guitariste anonyme, Freedom sera dissous en 1959. En décembre, Eddie s’est envolé pour un spectacle important à New York et revint en Californie participer au film à petit budget Go, Johnny Go (Paul Landres, 1959), tourné en cinq jours aux studios d’Hal Roach à Culver City. À l’affiche avec lui : les Cadillacs, les Moonglows, Jackie Wilson, Ritchie Valens et Chuck Berry. Alan Freed y jouait le rôle principal du découvreur de talents et Eddie y chante Teenage Heaven.

1959 Somethin’ Else

Sûr de lui avec trois succès dans la poche (Sittin’ in the Balcony, C’mon Everybody et Summertime Blues), Eddie Cochran avait beaucoup de recul sur sa carrière et ne confondait pas ses vrais amis avec les gens du métier qu’il était amené à fréquenter. Il leur préférait le tir, la pêche à la ligne, passait du temps en famille, avec ses vieux amis et avait la tête sur les épaules. Son ami et bassiste Connie Smith s’était marié et avait raccroché. Avec le succès de Summertime Blues, il lui fallait monter un groupe de scène. Eddie partit en tournée avec de nouveaux venus : Mike Henderson (sax), Jim Stivers (piano), Dave Shrieber (basse) et Gene Ridgio (batterie), The Kelly Four au personnel interchangeable. Eddie ne croyait pas beaucoup au show business et arrivait volontiers en retard (il a même loupé une invitation à l’Ed Sullivan Show, le spectacle le plus regardé de la télévision américaine !). Sur la route il préférait faire du tir dans les bois. Avec une nouvelle tournée dans le Mid West et nombre de séances en studio, il ne quittait plus sa nouvelle équipe. C’est avec eux qu’il enregistra Somethin’ Else, une chanson écrite par sa copine Sharon et son frère Bob — nouveau chef-d’œuvre adolescent, monté au numéro 58 à l’été et bientôt repris par Johnny Hallyday (« Elle est terrible »), Sid Vicious, les Stray Cats… mais Eddie en avait assez de tout ce cirque. Le succès, les tournées loin de Sharon et de ses amis l’ennuyaient. Il préférait le studio. Son tourneur American Music avait lancé la marque Silver et finançait des enregistrements du Kelly Four, Jewel Akens et Eddie Daniels (Jewel & Eddie), John Ashley, Darry Weaver auquel Eddie a participé. Capehart, son fidèle manager lui-même se désintéressait de son protégé. La dernière séance d’enregistrement fin 59 se déroula avec les Crickets (ex groupe de Buddy Holly) mais sans Capehart. Elle donna le magistral Cut Across Shorty et le tube posthume ironiquement intitulé Three Steps to Heaven. Capehart ne l’accompagna pas non plus en Angleterre, où Gene Vincent avait triomphalement précédé Eddie en décembre 1959 pour une tournée de douze dates sous la houlette de Larry Parnes (imprésario vedette du rock anglais). Gene avait été invité dans la populaire émission de télévision de Jack Good, Oh Boy!. Jack Good voulut capitaliser sur ce succès et invita Eddie et Gene à tourner ensemble.

1960 Three Steps to Heaven

Arrivé le 10 janvier à Londres, Eddie partit aussitôt sur la route. Comme tous les musiciens il disposait d’une chambre pour deux et partagea sa chambre d’hôtel avec son vieux copain Gene Vincent, qui avait commencé à s’habiller en cuir noir des pieds à la tête, une grosse médaille autour du cou. Good le lui avait demandé pour son émission de télé, et Gene garda ce costume sur toute la tournée. Ils étaient accompagnés par les Wild Cats du rocker anglais Marty Wilde. Gene et Eddie étaient inséparables ; Gene Vincent, boîteux à la suite d’un accident de moto et affecté par les déboires de sa carrière en chute libre, s’appuyait sur son ami Eddie, plus solide. Mais le succès était au rendez-vous : alors que les ersatz anglais n’étaient pas à la hauteur, ce sont les deux amis qui les premiers ont véritablement fait découvrir aux Britanniques ce qu’était le rock and roll. Pendant des mois, jusqu’en avril, les pionniers Eddie Cochran et Gene Vincent ont parcouru les routes de Grande-Bretagne, partageant ensemble toutes sortes de problèmes et d’instants de gloire. Mais Eddie buvait beaucoup, et l’Amérique lui manquait. Il dépensait de très fortes sommes en coups de téléphone intercontinentaux à sa famille. Sharon arriva de Californie pour fêter ses vingt ans avec lui le 4 avril. Après quatre mois de tournées et un ultime concert à Bristol, Sharon, Eddie, Gene et le régisseur Patrick Thompkins prirent enfin un taxi pour l’aéroport de Londres, situé à plus de cent cinquante kilomètres de là. Trop heureux de rentrer, ils avaient réservé un avion partant à une heure du matin, quelques heures après la fin du concert. Roulant à toute allure sur les petites routes de campagne, le chauffeur de dix-neuf ans George Martin a soudain été informé par le régisseur qu’il s’était trompé de route. Un coup de frein plus tard, le taxi quittait la route. Le régisseur et le chauffeur sortirent indemnes. Gene et Sharon furent sérieusement blessés. Eddie Cochran, éjecté dans les tonneaux, décèdera de ses blessures à la tête à quatre heures ce matin du lundi de Pâques 1960 à l’hôpital St. Martin de Chippenham. Il avait vingt et un ans.

Bruno Blum, lundi de Pâques 2013

Merci à Brian Setzer, Lee Rocker et Slim Jim Phantom.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Extrait du documentaire Cool Cats: 25 Years of Rock ‘n’ Roll Style, 1983.

2. Retrouvez Joe Maphis et Chet Atkins sur le triple album Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) et Chet Atkins sur Guitare Country (FA5007) dans cette collection.

3. Retrouvez Eddie Cochran dans « Guybo » sur Rock Instrumental Story (FA5426), un triple album dans cette collection.

4. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - vol. 1 1954-1956 (FA5361) dans cette collection.

5. Écouter Scotty Moore et Chet Atkins dans le coffret Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA5421) dans cette collection.

6. Écouter Ray Charles - Brother Ray: The Genius 1949-1960 (FA5350) dans cette collection.

7. Écouter The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1960-1962 (FA5406) dans cette collection.

8. Écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

9. Écouter The Indispensable Chuck Berry 1954-1961 (FA5409) dans cette collection.

10. Écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1946-1962 à paraître dans cette collection.

11. « Let’s Coast Awhile » de Bo Davis (alias Hank Cochran) avec Eddie Cochran à la guitare figure dans l’anthologie Road Songs - Car Tune Classics 1942-1962 (FA5401) dans cette collection.

12. Écouter les deux volumes de The Indispensable Bo Diddley 1955-1960 (FA5376) et 1960-1962 (FA5406) dans cette collection.

13. Lire la biographie John Lennon par Bruno Blum (Hors Collection, Paris 2005).

14. Écouter The Indispensable Little Richard à paraître dans cette collection.

15. Écouter The Indispensable Platters à paraître dans cette collection.

16. Écouter Eddie Cochran chanter les chœurs dans « Git It», «Teenage Partner », « Peace of Mind » et « Lovely Loretta » sur The Indispensable Gene Vincent (FA5402) dans cette collection.

17. Écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine - vol. 2 1956-1957 (FA5383) dans cette collection.

18. Retrouvez Johnny Burnette, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Elvis Presley et bien d’autres sur notre anthologie Rockabilly (FA5423) dans cette collection.

Eddie Cochran

The Indispensable 1955-1960

By Bruno Blum

“Eddie Cochran? He’s a… [he shows his guitar, the same as Cochran’s, and his hair style] He’s it! He’s my main man. The guy that really influenced me the most was Eddie Cochran. First it was just that album cover, standin’ like that with those big baggy pants. And then I said, ooh, this guy looks really cool, I want to look just like him. And then I bought the album and took it home, it just blew me away. I mean ‘Somethin’ Else’, that was just like a theme song, ‘she sure fine lookin’ man, she’s somethin’ else’. That was it. It was the best.”

— Brian Setzer, 1983.1

He was born Ray Edward “Eddie” Cochrane (with an “e”) on October 3, 1938 (d. April 17, 1960) in Albert Lea, Minnesota, a prosperous small farming community in the north of rural America whose population stifled in the summer and froze in winter. Eddie’s parents were from Oklahoma City, where his father Frank worked in a factory. The economic crisis of the Thirties obliged them to move north where, fortunately, Frank had found work in a household. The dramatic recession was worsened by repeated droughts, storms and plagues of insects, causing ruined families to swarm either north or west to California. Frank Cochrane was lucky to find work as a cleaner, and he and his wife Alice raised Gloria, Bill, Bob, Patty and Eddie, by six years the youngest addition to the family. His elder brother Bill had a Kay guitar and then a model made by Martin, but Eddie didn’t touch it often; he wanted to play drums at first, and then trombone. His other brother Bob took a serious interest in music and would later compose Hammy Blues with Eddie, together with the classics Three Steps to Heaven and Somethin’ Else.

Frank became a mechanic in 1946. His uprooted family was still very fond of Oklahoma and, like fellow major Minnesota musicians Bob Dylan and Prince (whose four grandparents came from Louisiana), Eddie had musical roots deep in the South. He was thirteen in 1951 when the Cochrane family moved to Los Angeles where Bill had already settled, but Eddie always took pride in their identity as Okies even though he’d never set foot in Oklahoma. He’d even sing about it in June 1959 in Boll Weevil, a traditional song named after the beetle which devastated southern cotton-plantations before the war: “Well if anybody should ask you / Who it was that sang this song / Say a guitar picker from Oklahoma City / With a pair of blue jeans on / Just looking for a home.”

The term boll weevil was also used to designate southern Democrats who had right-wing views (particularly concerning segregation). To those with little taste for such racist opinions, that kind of boll weevil was nothing more than pestilential, a widespread disease: they were traitors to the moderates’ cause. Such extremist views led more than one boll weevil to join the Republican Party led by President Eisenhower, the conservative General who remained in power throughout Eddie’s career (from 1953 to 1961, with Richard Nixon as his Vice President); Eddie was determined to succeed, and sang that he’d never be a Cotton Picker.

Strollin’ Guitar

In 1951 Frank Cochrane found work at a missile plant in Los Angeles. By the time Eddie was thirteen he already had a passion for the acoustic guitar, and was seemingly never without it. Separated from his friends by the family’s sudden move to 5539 Priory Street in the modest neighbourhood of Bell Gardens, Eddie considered his guitar his new best friend. At 15 he went to Bell Gardens Junior High School in East Los Angeles and met Conrad “Connie” Smith, who played the double bass in the school orchestra. Connie also played steel guitar and mandolin, and his new buddy shared his passion. At the end of 1953 they formed a trio — Connie on bass, a school-friend on lead guitar, plus Eddie on rhythm — and rehearsed in a back-room at Bell Garden Music Centre, a music-store whose owner Bert Keither encouraged teenagers and saw Eddie’s gifts. He found their first gigs for them (school dances, supermarket-openings, etc., all of them precious experiences) and Eddie spent the next year playing in his neighbourhood, where rhythm & blues and country music was a stronghold; he spent a lot of time with local musicians, absorbing influences and already dreaming of turning professional. He tried to master Chet Atkins’ difficult finger-picking technique (as did Elvis’ guitarist Scotty Moore, and literally every other country guitarist), and here you can listen to a picking demonstration on Country Jam, an instrumental in the very special bluegrass style. Eddie’s hands were small and delicate and could cover a large part of the fret board; he learned difficult country parts by Joe Maphis2 and techniques including the use of a thumbpick, as well as flat picks and several fingers (with or without a pick), assimilating the jazz played by Johnny Smith, Jimmy Wyble. People who knew him confirm he was curious, open, smart, and a quick learner. His adaptation of “The Third Man Theme” by Austrian composer Anton Karas became the Fourth Man Theme which shows how varied his tastes were. Other examples of Eddie’s eclecticism appear here, with influences ranging from bluegrass and country to blues and rock. Rock guitar-instrumentals had been in fashion since Earl Hooker’s “The Hucklebuck” (1953) and Bill Doggett’s “Honky Tonk” in 1956; influenced by Duane Eddy’s hit “Rebel Rouser” in 1958 and his new “twang” style played on a Gretsch guitar, Cochran investigates this instrumental vein at the end of CD3, notably on Strollin’ Guitar, which is characteristic of this quite separate genre.3

The Cochran Brothers

In October 1954 Eddie was introduced to Hank Cochran, an orphan and local boy who’d been through hard times and had turned semi-professional; Hank quickly asked Eddie to play with him, taking solos and singing back-up. Duos featuring brothers weren’t unusual in country music (the McGee or Stanley Brothers, the Monroes, and soon the Everly Brothers…); Hank and Eddie almost had the same surname and decided they’d be the Cochran Brothers. In January 1955, aged exactly sixteen years and four months, Eddie quit school for good and went on the road. Hank was a determined singer/rhythm guitarist and after a few rehearsals they toured California, finding gigs even though Eddie wasn’t old enough to play in places where alcohol was sold. That same year, Eddie acquired a Gretsch 6120, the firm’s new hollow-body electric guitar. It cost him $385 at the Bell Garden Music Centre, and was equipped with a Bigsby tremolo arm which enabled him to play some new effects (cf. Eddie’s Blues and its highly original style); until then, the sound had been the preserve of Chet Atkins, another Gretsch adept. Eddie modified his guitar, swapping its bass pick-up for a Gibson P-90.

The Bell Gardens Music Centre was one of the local musicians’ favourite haunts and it was there that Bert Keither introduced Eddie to Jerry Capehart. Jerry was a farmer’s son (a man ruined in the Thirties who’d immigrated to California in a Ford Model T), and he loved country music; he played violin in a semi-professional group, and had been mobilised during the Korean War. Too poor to realize his ambition to be an attorney, Jerry had been working a night-shift at an aircraft-plant since 1953; he wrote songs, but his voice wasn’t good enough and he’d been looking for musicians who could sing and record his compositions. The Cochran Brothers agreed to play a few of them and record a demo.

In April ‘55 the two “brothers” were hired by Steve Stebbins of the American Music Corporation, California’s principal country music agency (working also for Merle Travis, Tennessee Ernie Ford etc), and Stebbins totally changed their career. He got to work on their promotion and they were invited to appear on Home Town Jamboree, the TV show hosted by his associate Cliffie Stone, and on the popular radio show Town Hall Party. They were also introduced to Red Matthews at the independent record-label Ekko. Marked by Hank Williams’ plaintive style, their first recordings open this album: Mr. Fiddle and Two Blue Singing Stars (a tribute to Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams) feature Eddie’s voice and some very country-sounding guitar. Their first single was released that summer, leading to a concert at the Big D Jamboree in Dallas aired by KLRD, the popular local station.

They had been preceded only a few days earlier by Elvis Presley, whose new style mixing country and rhythm & blues had left a deep impression on audiences used to a more “grandfatherly” kind of music: Elvis was more than a singer, a Phenomenon, with all the accompanying screams and faints and security people — they couldn’t cope — which one associates with it, plus music that was fresh and exciting and in total contrast with conventional country music. The Cochran Brothers suddenly realized how popular rockabilly was: a new rock style which added country-rooted guitar to African-American rhythm and blues. Until then, white audiences didn’t know much about rock. Hank and Eddie were poor, and life was difficult on the road: they once had to hitch a ride home after a trip to Memphis to see Exxo’s offices. Back in LA they accompanied Jerry Capehart on an (average) 45rpm single recorded with black musicians (produced by John Dolphin for Cash Records), and then in January 1956 they toured the West Coast, moving up as far as the state of Washington. In California they were regular guests on KORV TV, and also accompanied Jack Wayne, a DJ at KVSM radio who copied Johnny Cash, other country artists... Their records were failures but their TV appearances saw their popularity grow, and Jerry Capehart, who was more and more active, sang on stage with them in March. He also set up other sessions for them to accompany hillbilly artists he introduced to Dolphin, and he became the de facto manager of the Cochran Brothers. Capehart had good contacts with their agency American Music, a major firm which had created Crest Records as an outlet for the numerous talents they sent out on the road; and American Music didn’t neglect to publish their songs in exchange for a substantial share of their royalties. Even so, bound to the cause of “grandpa’s” country music by a catalogue filled with hillbilly classics (Merle Travis, Roy Rogers, Delmore Brothers, etc.), American Music found itself increasingly trailing behind the innovations in rock, which was now taking off and finding a mass audience.

Rockabilly

In 1956, after eighteen months of Elvis hits for the little Sun label, RCA Records bought Presley and gave him a massive boost. The instantaneous success of his first 45rpm single for RCA, “Heartbreak Hotel”, sent shock waves through the record-industry in January 1956.4 For several months, this white artist had been successfully singing rock songs, a style hitherto reserved for Afro-Americans. And a number of those songs had been composed by black and mixed-race writers. Elvis’ original producer Sam Phillips had paired him with Scotty Moore, a guitarist who played in the hillbilly style that was an emblem of southern Whites, and the resulting mixture of rhythm and blues and hillbilly was a new rock ‘n’ roll style they called rockabilly. Like Eddie, Scotty Moore was very influenced by Chet Atkins5 and this gave a “white” colour to reprises like Milk Cow Blues written by Kokomo Arnold (the Eddie Cochran version here was inspired by Elvis’ cover). Elvis Presley’s success was out of all proportion, and it brought rock to a white audience en masse. Exciting, liberating and urging people to dance freely, rock had long found favour with black audiences in forms known as jump blues, rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm and blues… all of them terms with racial connotations. And in an America where racial segregation had been institutionalized for centuries, by 1955 Afro-American artists like Ray Charles6, Bo Diddley7, Little Richard8 and Chuck Berry9 were beginning to break through, despite their colour, to reach white audiences. Rock ‘n’ roll disturbed conservative America but it was played by little groups who were easy to transport, and it hit the jackpot. Tried and trusted Afro-American tunes were often unknown to white audiences, and new versions by white artists were guaranteed to sell. RCA’s competitors, naturally, actively sought out white artists capable of rivalling the Presley phenomenon, as confirmed by the success of the pioneering Bill Haley10 and his Comets with their “anthem” entitled “Rock Around the Clock”. It came at exactly the same time when Jerry Capehart was placing one of his songs with Jack Lewis, whose records were financed by two scouts for Crest Records, Ray Stanley and Dale Fitzsimmons. The version by Jack Lewis had no success at all, but Capehart’s composition had been taken from the convincing demo recorded by the Cochran Brothers… and the two scouts from Crest were quick to see that Eddie was worth his weight in gold. They set up a recording-session for the Cochran Brothers so that Eddie could try his luck with a microphone all to himself.

Aged seventeen, Eddie made his first record under the “Cochran Brothers” name, and it was a flashing rockabilly masterpiece; he sang it alone, accompanying himself on the guitar, with backing from his friend Connie on double bass and a distant percussion. Based on the same vestimentary theme as Blue Suede Shoes (the rockabilly tune by Carl Perkins which Eddie also recorded a month later), the subject of his first recording Pink-Peg Slacks is his irrepressible desire for a pair of loose (pink) trousers tapering to a tight fit around the ankles. In the song, his girlfriend asks her father to lend her the money so that he can buy himself this bottom half of a “zoot” suit… By all accounts, Eddie was a great seducer. His “inhabited” performance also shows that he was a singer of unmatched charisma.

The failure of the single Tired and Sleepy/Fool’s Paradise brought the career of the Cochran Brothers duo to an end. The dominant Jerry Capehart was ten years his elder, and he and Eddie definitively adopted the fashionable rock style, completely abandoning country music. Hank Cochran was married and not made for rock; he didn’t want to follow Capehart’s new direction. At the following session, Eddie accompanied Hank Cochran on guitar, an amiable end for the duo. Hank Cochran’s only rock record would be released under the pseudonym Bo Davis.11

1956 Twenty Flight Rock

“Merit counts not the years for souls who are well born.”

— Pierre Corneille

In the wake of Elvis, some major singers sprang up, like Gene Vincent with “Be-Bop-A-Lula”, but Gene, like the extravagant Little Richard, was no soloist; Elvis had great charisma, a golden voice, and he was a great dancer, but he was no composer (even though he did sign a few pieces which weren’t written by him), nor was he a good guitarist. All three of them needed instrumentalists. Jerry Lee Lewis hardly ever wrote his own songs. Carl Perkins was a composer, and also played lead guitar, but even though he was the creator of Blue Suede Shoes (Eddie’s version is included here), he didn’t have the calibre of his co-religionists. As for Johnny Burnette, his trio broke up too quickly. None of those rock giants possessed the totality of Eddie Cochran’s gifts. The sweetened, commercial rock of Pat Boone, Ricky Nelson, Frankie Avalon, Fabian or Paul Anka was just around the corner; yielding to pressure from his producer, the young Eddie had already recorded several “sweeter” pieces with a vocal group reminiscent of the formula used by Elvis Presley with the Jordanaires (cf. CD2), but Eddie steered an uncompromising rock course as soon as he was allowed to do so.

So at 17 the precocious Eddie Cochran was a first-rate solo performer. He had an ambitious manager/lyricist (Jerry Capehart), a top-flight agent planning his tours, a record company, and a team of composers from American Music — among them Stanley and Fitzsimmons — who were ready to do anything for him to record their compositions in the new rockabilly style. Whatever else was said, Eddie Cochran already had everything going for him, and more trumps up his sleeve than any of his competitors. Not only was he handsome, intelligent, ambitious, elegant, charming and seductive; he was also an irresistible singer and a proficient guitarist, and to cap it all he could write a classic like Twenty Flight Rock. In this song, Cochran the singer/songwriter tells how he has to climb the stairs because the elevator is out of order, and when he gets to the 20th floor he’s so exhausted he can’t “rock” his girlfriend… but that doesn’t stop him coming back again and again. In a way, Cochran was “the white Chuck Berry”; but if you actually compare them, when Chuck recorded his first classics in 1955-56 he had the experience of a thirty-year old male adult — whereas Eddie was a mere seventeen. Buddy Holly, who also died young (Eddie sings a song in his memory here, Three Stars), cut a number of remarkable records during this period, but didn’t live long enough to reach full bloom; Eddie, on the other hand, recorded a whole series of essential titles in only three years. Like the immense singer-guitarists Bo Diddley12 and Chuck Berry, Eddie Cochran combined the originality of a great performer with first-rate compositions. Praise could he heaped on Cochran for a long time: one would have to vaunt the merits of his spontaneity, and the aesthetic simplicity of any number of major recordings without even a set of drums behind him: just Capehart tapping on an old box with his fingers.

In May 1956 the Cochran Brothers reached the peak of their modest career opening concerts for Lefty Frizzell, a country celebrity, and went on to work summer weekends in a club in Escondido, California. Eddie had an excellent reputation in the area as a guitarist and recorded for Capitol with different country artists like Wynn Stewart (“Keeper of the Keys”) or the rockabilly artist Skeets McDonald (“You Oughta See Grandma Rock”). As a stage- and studio-performer with a lot of experience, combined with gifts as a solid guitarist and singer whose range encompassed not only romantic songs but also future punk hymns, Eddie Cochran went straight to the essential, leaving country by the wayside when he chose rock. His rockabilly record Skinny Jim, released shortly afterwards in that summer of 1956, was a flop, but that didn’t discourage him. When associated with its Afro-American creators, the rock style still reeked of the devil. While Hank Cochran and other country singers were recording rockabilly under pseudonyms for fear of being excluded by a conservative country audience, Eddie would record the current Afro-American rock hits to proclaim his belonging to the movement which was so seductive to young people, releasing Long Tall Sally by Little Richard and I Almost Lost my Mind by Ivory Joe Hunter. He also cut his own version of one of the first real rockabilly hits, the brand-new Blue Suede Shoes by Carl Perkins.

Capehart took these new recordings to Liberty, the little record-label owned by Hungarian violinist Simon “Si” Waronker, who’d just had a nice little hit with Julie London (accompanied by Barney Kessel) singing “Cry Me a River”. Waronker was very conservative and had ties with Lionel Newman, the musical director at 20th Century Fox film-studios (he’d provided Fox with tapes of music for several films). With The Chipmunks and Henry Mancini on its roster, the artist-choice at Liberty was just as conservative and, as with many other companies, the stable needed a rock singer… The Presley phenomenon was upsetting every habit in the business and Capitol had just released Gene Vincent’s first single, the huge hit “Be-Bop-a-Lula”. There was no time to lose. Waronker could see all that, and he was quickly won over by the maturity, seductiveness and talent displayed by Cochran. At the same time (July ‘56), while Eddie was working on the soundtrack for a film with a small budget, producer Boris Petroff offered him a role as a singer in his next film. He asked him for songs, and one was Twenty Flight Rock, recorded almost overnight with Capehart slapping a box and Connie Smith playing slap-style bass like Bill Black did with Elvis Presley. In the song, Eddie produced a pastiche of all Presley’s mannerisms with great assurance: a rockabilly classic was born. It opened the doors to film-studios and success. The song was also one of the very first ones Paul McCartney learned, and when Lennon heard Paul sing Twenty Flight Rock to perfection at the school party (the day was July 6, 1957) he had him join his group — and The Beatles were born.13

1957: Singin’ to my Baby

After other rockabilly gems like Teenage Cutie, Eddie was just eighteen when Waronker urgently asked him to record Sittin’ in the Balcony, which had already been a success for John D. Loudermilk (under the pseudonym Johnny Dee). This sugary commercial ballad filled with charm was Eddie’s first single for Liberty, and it would sell over a million copies. Cochran didn’t like it but he never complained about its success: it went to N°18 in April 1957, four months after the release of the film The Girl Can’t Help It (Frank Tashlin, 1956) in which Eddie, in one of his rare screen performances, sang Twenty Flight Rock. Tashlin’s rock-movie classic borrowed its title from the Little Richard song14 (and you can see the latter onstage in the film). Also in the credits were Gene Vincent, The Platters15, The Treniers, Abbey Lincoln, Julie London, Fats Domino… and the star of the film, Jayne Mansfield.

Early in 1957 Eddie Cochran played a role in another film, “Untamed Youth” (its subject was young rockers in the margins of society) and then went on a concert-tour across the United States, with appearances on major radio and TV shows (like Dick Clark’s Bandstand). It was in April 1957 that he met singer Gene Vincent at the Mastbaum Theatre in Philadelphia, and the two became friends.

The success of Sittin’ in the Balcony logically led Si Waronker to produce other commercial ballads, and a glimpse of these appears on CD2. The second single, One Kiss (May 1957) was an exercise to which Eddie submitted without enthusiasm — and it was a total flop. The inseparable Jerry and Eddie jumped at their first chance to record at the little Goldstar studios, and it was there that they recorded their first album, “Singin’ to my Baby”. Waronker imposed the Johnny Mann Singers on them, and the whole album reflects the tension between the edgy, free, ultra-sober rockabilly of which Eddie was capable — cf. Am I Blue (which didn’t appear on the American album-release) or Twenty Flight Rock — and the more “poppy entertainment” sound (I’m Alone Because I Love You) of the majority of the titles (producer Simon Jackson had been recruited by Liberty, and was taking that direction). So the album wasn’t representative of Cochran’s true style; he wasn’t yet nineteen and already entangled inside the artistic leanings of a success that escaped his control. Released in the autumn of 1957 when rock was at the height of fashion, and when the sales-charts were being hammered by monster hits such as “Let’s Go to the Hop” (Danny & The Juniors) or “Keep-a-Knocking” (Little Richard), the charming single Drive-In Show wasn’t that successful, but sold enough for the DJs to remember it (and Eddie).

Eddie Cochran dressed like the sports-jocks in American colleges, and used to wear loafers, wide slacks, broad tweed jackets and a tie; they were useful equipment for a seductive “teen idol” to have, and quite different from the “bad boy” type of clothing worn by Gene Vincent. A fine Australian tour together with Gene and Little Richard took place that October. Accompanied by The Deejays, the group who backed local rock star Johnny O’Keefe, Eddie played some memorable concerts where Little Richard would start a riot with his provocative stage-act. The Aussie teenagers demolished everything including the artists’ clothes, and the press had a field day. Gene Vincent topped the bill and had his work cut out to stave off the creator of Long Tall Sally, but he’d had a year to get his own act together and he, too, created hysteria — as Elvis had been doing every day back home. Eddie Cochran had polished his stage-act also, although he wasn’t as demonstrative, and he had his own share of success, particularly with the ladies. This was the last tour by Little Richard: right in the middle of it, he quit the tour to devote himself to theology, and that made headlines, too… Eddie had barely returned to the USA before he set off on another tour with Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Paul Anka, Buddy Holly… and it was in his dressing-room at the Paramount in New York that Phil Everly introduced him to Sharon Sheeley, his future girlfriend.

On his return to Los Angeles Eddie went back to being a studio musician, running Dot sessions for his friend Bob Bull (aka Bob Denton); three singles came out of it, plus a number of demos he recorded for Ray Stanley, most of which are lost today. A dozen of the Ray Stanley titles with Eddie on guitar were released by various labels including Crest and Argo. Apart from his other numerous talents, the young Eddie had turned into a studio professional and was capable of suggesting various arrangements, not to mention leading sessions on his own; on one of them he accompanied Lee Denson, for an obscure single on the Vik label, and also played guitar for singers Paula Morgan or Don Deal…

1958: Summertime Blues

Poor sales moved Liberty to let Eddie direct his own sessions, beginning in January 1958. It was an unusual step for producers to take in those days — especially for a producer as conservative as Waronker. Nor was it a common opportunity for someone as young as Si Waronker’s protégé. It took a weight off Eddie’s mind and at last he could show what he could do. Unsurprisingly, Cochran and Capehart chose to record rock songs: the excellent Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie came very close to success, as did Pretty Girl which they recorded a few weeks later. On March 25-26 1958, at Capitol Studios, Eddie also sang bass harmony on four titles by his friend Gene Vincent.16

But rock was already set quite apart from the rest of show business. The music had a bad reputation: infested with opportunity-seeking singers who used pseudonyms, often dishonest and corrupt producers, careerist disc-jockeys, the rock milieu was disdained by most of the established professionals; they preferred music that was much more conservative. Concert venues preferred much calmer artists, too, so they didn’t welcome rock music; they considered it vulgar, music for rude teenagers. And then there was racism, a commonplace: some people didn’t take to Whites being so influenced by typically Black artists’ styles that they actually recorded their compositions; they liked even less the fact that Afro-American singers (Bo Diddley, Frankie Lymon…) had reached a mass audience playing in a genre they judged to be “inferior”. But rock was big business: it sweetened the pill, and doors were opening. Nobody, however, thought that this phenomenon would last; it was just a question of jumping on the bandwagon while there was money to be made. Under a hail of unfair criticism, Elvis Presley himself was already branching out into other repertoire, not only out of personal taste but also because he was realistic.17 In 1958 the tendency was for rock to be a sweetened form of insipid entertainment, tinted with vague rock imagery and the accents of teen idols like Ricky Nelson, who was an enormous hit with audiences. Secretly in love with Eddie, young Sharon Sheeley had put her name to one of Ricky’s big hits (“Poor Little Fool”) and managed to sell her romantic ballad “Love Again” to Capehart, who asked Eddie to record this monotonous little ditty. And he did so promptly, taking advantage of the opportunity to seduce young Sharon. All that the new single needed was a B-side: based on the riff in its intro (played on a Martin guitar), the great classic Summertime Blues was written inside an hour as the B-side of the ordinary “Love Again”. Released on June 11th 1958, a month after another flop (Teresa), the single written and produced by Cochran and Capehart climbed to N°8 on the charts in two months. Naturally, DJs preferred the B-side, and the single was flipped: Summertime Blues (an apt title for a summer hit) became the A-side and at the same time the definition of this new rock style created by Eddie Cochran. He would leave rockabilly behind him for good; the new sound became a statement of his personality.

In September 1958 Liberty Records created the sub-label Freedom devoted to rock, and they gave carte blanche to Jerry Capehart, the impresario for Eddie Cochran, John Ashley and the excellent Johnny Burnette and his Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio.18 After 26 singles, most of which were mediocre (Capehart had to respect a production-quota), and in which Eddie participated as an arranger and anonymous guitarist, Freedom was dissolved in 1959. In December Eddie flew to New York for an important concert and then returned to California for the small-budget film Go, Johnny Go (Paul Landres, 1959), which was shot in five days at Hal Roach’s Culver City studios; Eddie shared the billing with The Cadillacs and The Moonglows, Jackie Wilson, Ritchie Valens and Chuck Berry, with Alan Freed in the principal role as a talent scout. The film has Eddie singing Teenage Heaven.

1959 Somethin’ Else