- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

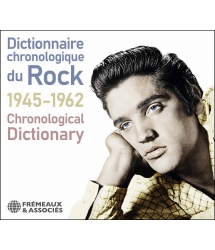

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

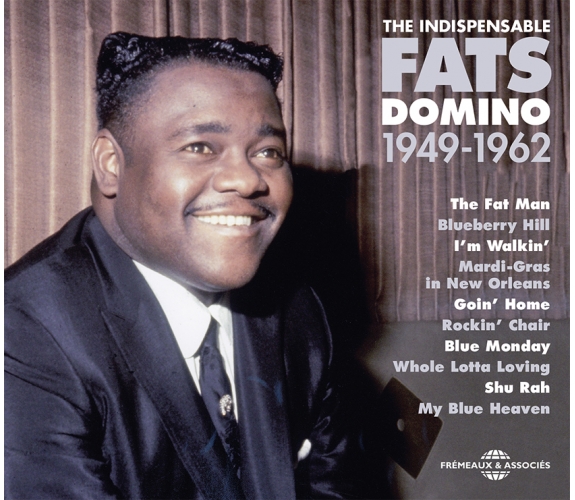

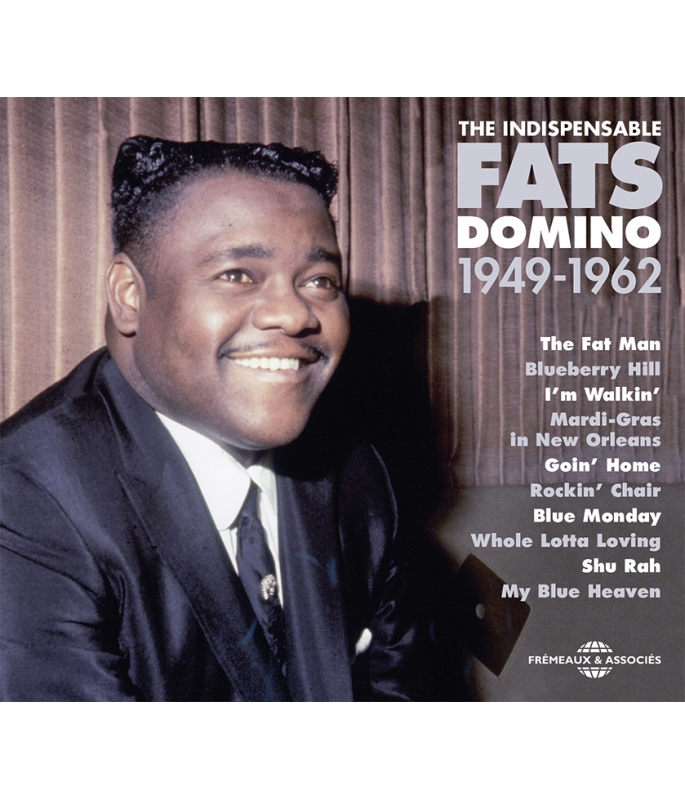

FATS DOMINO

Ref.: FA5692

EAN : 3561302569222

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 4 hours 32 minutes

Nbre. CD : 6

It is out of New Orleans that Fats Domino surged up to become the greatest black star of the 1950s and the first true rock superstar — a giant among giants. His worldwide hits, such as “Blueberry Hill,” became so famous that they overshadowed the best of his excellent output. Yet one should not overlook the great blues performer, the Boogie Woogie piano virtuoso and the fundamental pioneer who let the world first discover the rock genre. Domino managed to cross over to the white, general public, and embodied racial segregation tensions during the early Civil Rights movement. Bruno Blum tells the unthinkable triumph of this simple man who, far from his smiling image, caused riots all over the country. There is no way around these six discs, which are indispensable to any rock or blues lover. This hand-picked selection highlights the cream of often overlooked works by an essential figure. — PATRICK FRÉMEAUX

FIRST & SECOND LINE IN NEW ORLEANS, 1990-2005

ELVIS PRESLEY & THE AMERICAN MUSIC HERITAGE...

1937-1946

THE STORY OF THE NEW ORLEANS JAZZ, BLUES, ZYDECO &...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Fat ManFats DominoFats Domino00:02:371949

-

2Hide Away BluesFats DominoFats Domino00:02:241949

-

3She's My BabyFats DominoFats Domino00:02:401949

-

4Little BeeFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:281950

-

5Boogie Woogie BabyFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:161950

-

6Hey ! Là-Bas BoogieFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:241950

-

7Careless LoveFats DominoW.C. Handy00:02:151950

-

8Hey! Fat ManFats DominoFats Domino00:02:351950

-

9What's The Matter BabyFats DominoFats Domino00:02:131951

-

10I'Ve Got Eyes For YouFats DominoFats Domino00:02:381951

-

11Stay AwayFats DominoFats Domino00:02:131951

-

12Don'T You Lie To MeFats DominoTampa Red00:02:181951

-

13Rockin' ChairFats DominoFats Domino00:02:271951

-

14Sometimes I WonderFats DominoFats Domino00:02:211951

-

15Right From WrongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:141951

-

16You Know I Miss YouFats DominoFats Domino00:02:131951

-

17I'll Be GoneFats DominoFats Domino00:02:191951

-

18Reeling And RockingFats DominoFats Domino00:02:191952

-

19Goin' HomeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:101952

-

20How LongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:011952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1No No BabyFats DominoFats Domino00:02:191951

-

2The Fat Man's HopFats DominoFats Domino00:02:251951

-

3Long Lonesome JourneyFats DominoFats Domino00:02:271952

-

4Trust In MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:481952

-

5Cheatin'Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:361952

-

6Mardi Gras In New OrleansFats DominoProfessor Longhair00:02:171952

-

7I Guess I'll Be On My WayFats DominoFats Domino00:02:171952

-

8Nobody Loves MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:121952

-

9DreamingFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:191952

-

10Going To The RiverFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:291953

-

11I Love HerFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:041953

-

12Second Line JumpFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:321953

-

13Swanee River HopFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:461953

-

14Rosemary Version 1Fats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:001953

-

15Please Don't Leave MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:341953

-

16Domino StompFats DominoFats Domino00:01:551953

-

17You Said You Love MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:341953

-

18Rose Mary Version 2Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:151953

-

19Ain'T It GoodFats DominoFats Domino00:02:361953

-

20Fats Domino Blues (Instrumental)Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:251953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Girl I LoveFats DominoFats Domino00:02:061953

-

2Don'T Leave Me This WayFats DominoFats Domino00:02:181953

-

3Something's WrongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:411953

-

4Fat's Frenzy (Instrumental)Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:231953

-

5Goin' Back HomeFats DominoFats Domino00:01:551953

-

6You Left MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:031953

-

7“44”Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:291953

-

8Barrel HouseFats DominoFats Domino00:02:291953

-

9Little School GirlFats DominoFats Domino00:02:381953

-

10If You Need MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:031953

-

11You Done Me WrongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:031953

-

12Baby PleaseFats DominoFats Domino00:01:561954

-

13Where Did You StayFats DominoFats Domino00:02:011954

-

14I Lived My LifeFats DominoFats Domino00:01:591954

-

15Little MamaFats DominoFats Domino00:02:391954

-

16I KnowFats DominoFats Domino00:02:381954

-

17Love MeFats DominoFats Domino00:01:551954

-

18Don'T You Hear Me Calling YouFats DominoFats Domino00:02:071954

-

19Don'T You NowFats DominoFats Domino00:02:201955

-

20Helping HandFats DominoFats Domino00:02:061955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1All By MyselfFats DominoFats Domino00:02:221955

-

2Ain'T That A ShameFats DominoFats Domino00:02:251955

-

3La LaFats DominoFats Domino00:02:131955

-

4Blue MondayFats DominoFats Domino00:02:161955

-

5Troubles Of My OwnFats DominoFats Domino00:02:131955

-

6I'M In Love AgainFats DominoFats Domino00:01:541955

-

7Bo WeevilFats DominoFats Domino00:02:471955

-

8Don'T Blame It On MeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:411955

-

9If You Need Me 2Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:021955

-

10Howdy PodnerFats DominoFats Domino00:02:081955

-

11So LongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:111955

-

12I Can'T Go On This WayFats DominoTerry Hall00:02:101955

-

13My Blue HeavenFats DominoA. Whiting00:02:061955

-

14Ida JaneFats DominoFats Domino00:02:091956

-

15When My Dreamboat Comes HomeFats DominoCliff Friend00:02:191956

-

16What's The Reason Why I'M Not Pleasing YouFats DominoEarl Hatch00:02:011956

-

17The Twist Set Me FreeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:001956

-

18Blueberry HillFats DominoVincent Rose00:02:191956

-

19Honey ChileFats DominoFats Domino00:01:461956

-

20What Will I Tell My HeartFats DominoP. Tinturin00:02:261957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I'M Walkin'Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:091957

-

2I'M In The Mood For LoveFats DominoJimmy McHugh00:02:421957

-

3My HappinessFats DominoBergantino Biagio00:02:141957

-

4Don'T Deceive MeFats DominoFats Domino00:01:521957

-

5The Rooster SongFats DominoFats Domino00:02:051957

-

6Oh! WheeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:061957

-

7My Love For HerFats DominoFats Domino00:02:371957

-

8Don't You Know That I Love YouFats DominoFats Domino00:02:091958

-

9(I'll Be Glad When You Re Dead) You Rascal YouFats DominoTheard Sam00:02:361958

-

10Young School GirlFats DominoFats Domino00:01:541958

-

11Lazy WomanFats DominoFats Domino00:01:471958

-

12Whole Lotta LovingFats DominoFats Domino00:01:381958

-

13Lil Liza JaneFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:01:521958

-

14When The Saints Go Marching InFats DominoInconnu00:02:251958

-

15I'M ReadyFats DominoFats Domino00:02:031959

-

16Want To Walk You HomeFats DominoFats Domino00:02:191959

-

17Easter ParadeFats DominoIrving Berlin00:02:261959

-

18Be My GuestFats DominoFats Domino00:02:151959

-

19Walking To New OrleansFats DominoFats Domino00:01:591959

-

20Don'T Come Knockin'Fats DominoFats Domino00:01:571959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1La La 2Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:021959

-

2Shu RahFats DominoFats Domino00:01:401960

-

3My Girl JosephineFats DominoFats Domino00:02:021960

-

4It Keeps Rainin'Fats DominoFats Domino00:02:461960

-

5What A PriceFats DominoFats Domino00:02:211960

-

6Ain'T That Just Like A WomanFats DominoClaude Demetrius00:02:431960

-

7Fell In Love On MondayFats DominoFats Domino00:01:551960

-

8Trouble In MindFats DominoMarigny Jones Richard00:02:301961

-

9Bad Luck And TroubleFats DominoFats Domino00:02:401961

-

10I Just CryFats DominoFats Domino00:02:061961

-

11Ain'T Gonna Do ItFats DominoFats Domino00:02:041961

-

12Won'T You Come On BackFats DominoFats Domino00:02:181961

-

13Good Hearted ManFats DominoFats Domino00:02:241961

-

14Trouble BluesFats DominoCharles Brown00:02:411961

-

15Let The Four Winds BlowFats DominoTraditionnel00:02:171961

-

16What A PartyFats DominoFats Domino00:01:591961

-

17Jambalaya (On The Bayou)Fats DominoHank Williams00:02:221961

-

18Stop The ClockFats DominoFats Domino00:02:191962

-

19Hum Diddy DooFats DominoFats Domino00:01:541962

-

20Dance With Mr. DominoFats DominoFats Domino00:02:041962

FA5692 Fats Domino

THE INDISPENSABLE

Fats

Domino

1949-1962

The Fat Man

Blueberry Hill

I’m Walkin’

Mardi-Gras

in New Orleans

Goin’ Home

Rockin’ Chair

Blue Monday

Whole Lotta Loving

Shu Rah

My Blue Heaven

The Indispensable Fats Domino 1949-1962

par Bruno Blum

Il n’y a pas de précurseurs, il n’y a que des retardataires.

— Jean Cocteau

Fats Domino fut rien moins que la première véritable superstar du rock – des années avant Little Richard, Bill Haley1 et Elvis Presley2.

On dirait que beaucoup pensent que j’ai lancé cette affaire. Mais le rock ‘n’ roll était là bien

avant que j’arrive. Il faut regarder les choses en face: Je ne peux pas chanter comme Fats Domino. Je le sais.

— Elvis Presley

Fats Domino fut l’un des plus gros vendeurs de disques des années 1950. Au point que ses énormes succès comme Blueberry Hill ou I’m Walkin’ ont fait beaucoup d’ombre au reste de sa discographie, qui est d’une grande qualité et d’une grande variété. Qui se souvient de son piano boogie virtuose, de ses blues très sentis, de ses charmantes balades candides ou de ses rocks au tempo rapide ?

Dans un contexte de ségrégation raciale sévère, il fut de loin l’artiste noir le plus célèbre des années rock originelles, devançant très largement Little Richard et Chuck Berry en popularité. Ses douze ans avec les disques Imperial ont rendu possible l’inimaginable triomphe du rock originel, authentique, et ce dès 1950. Avec naturel, simplicité et gentillesse, cet artiste consensuel était capable d’alterner des blues et de vieilles chansons populaires avec des rocks nerveux qui ont fait fredonner et danser toute une génération. C’est en partenariat avec son brillant producteur et arrangeur Dave Bartholomew que Fats Domino a séduit l’Amérique avec son éternel sourire, ses chansons gaies, aux rimes directes et efficaces. Little Richard reprenait ses chansons sur scène et emprunta bientôt son équipe, avec laquelle il enregistra à son tour une série de grands succès essentiels3.

Il était tout pour moi. Je me suis senti honoré de lui serrer la main. Je ressens toujours cela pour Fats Domino.

— Little Richard

Modeste, bon enfant et père de famille, avec l’aide des meilleurs musiciens de la Nouvelle-Orléans Fats Domino a créé un style original extrêmement influent qui marqua profondément Little Richard, Elvis Presley, jusqu’aux Beatles, aux artistes de soul et aux musiciens de reggae jamaïcains (sa partie de piano à contretemps sur It Keeps Rainin’ en 1960 est étrangement annonciatrice du reggae). Solide pianiste au style personnel, avec ses très influents triolets comme marque de fabrique, utilisant un rythme personnel bien à lui, chanteur à la voix douce, sincère et touchante, cet homme simple et sans façons était issu d’une famille nombreuse pauvre. C’est tout naturellement qu’il a accompli la synthèse de l’héritage créole et afro-caribéen des musiques populaires de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ville-clé et ville source des musiques afro-américaines au XXe siècle4. Le brillant Fats Domino s’est révélé capable de propulser son héritage créole français au sommet et de séduire le grand public blanc, comme le grand pionnier de l’intégration Louis Armstrong l’avait fait un quart de siècle plus tôt, toujours à partir de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Sous la pression du succès, à partir de 1957 après sept ans d’un prolifique et lucratif âge d’or, il fut amené à enregistrer de plus en plus de chansons commerciales éloignées de son vrai style — elles ont été écartées ici —, ce qui annonça sa chute. Après plus de cinquante impensables et énormes succès de blues et de rock dans son pays, Fats Domino, héros populaire d’une génération, sombra presque dans l’oubli après ses dernières séances pour Imperial en 1962. Ce coffret met en valeur ses meilleurs enregistrements, dont un grand nombre de morceaux négligés auxquels ses grands succès ont fait beaucoup d’ombre. Ils ont été sélectionnés parmi plus de deux cents titres pour la plupart gravés pour Imperial avec Dave Bartholomew et son équipe. Détestant de plus en plus les tournées, le chanteur refusa finalement de quitter sa ville (il bouda même une invitation à jouer à la Maison Blanche) et vécut le reste de sa vie en famille dans une jolie maison construite dans son quartier populaire, qu’il n’a jamais quitté — et où il se déplaçait dans sa Cadillac Eldorado rose.

Vacherie

Plusieurs générations de la famille Domino ont vécu et travaillé en tant qu’esclaves dans les immenses plantations de canne à sucre de Vacherie, au bord du Mississippi, à une cinquantaine de kilomètres à l’ouest de la ville. Le premier Domino recensé dans la région était un mulâtre répondant lui aussi au nom d’Antoine Domino, né à Vacherie en 1824. Il faisait vraisemblablement partie d’une famille déjà substantielle. Émeline, la mère de Carmelite (grand-mère de Fats Domino), avait été séparée de son mari et vendue en 1860; Carmelite vécut en domestique sur la plantation Gold Star où elle eut quatre enfants, dont le dernier fut le père de Fats Domino. Elle était une sage-femme respectée, une experte en herboristerie et prêtresse animiste héritière de traditions africaines mystérieuses, capable de faire le bien comme le mal selon la tradition hoodoo qui imprègne la culture et la musique de la Louisiane5. Avant de décéder âgée en 1944, elle put admirer son petit-fils de seize ans maîtriser le piano. Mais jamais cette fille d’esclave n’aurait pu imaginer ce qui allait suivre6.

C’est en 1682 que l’explorateur René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle donna son nom à la Louisiane en l’honneur du roi de France, Louis XIV. La France céda la Louisiane à l’Espagne lors du traité de Paris en 1763 (elle sera restituée à la France en 1800 puis vendue aux États-Unis le 3 mai 1803), mais la langue française perdura chez les colons français et leurs esclaves, qui étaient de toute façon isolés du reste du monde. Ce fut le cas dans la gigantesque plantation Laura à Vacherie. Vers 1800 la révolution haïtienne mit en fuite des planteurs francophones qui s’installèrent dans la région avec des milliers d’esclaves. En 1811, plus de cinq cents esclaves haïtiens se révoltèrent et furent massacrés. Certains rejoinrent des camps de marrons et quelques-uns trouvèrent la liberté; comme les nombreux esclaves cubains exilés à la Nouvelle-Orléans, ils ont beaucoup contribué à l’identité afro-caribéenne de la Louisiane, mise en évidence ici sur des titres comme Mardi-Gras in New Orleans ou Don’t You Hear Me Calling You7. À la suite de cette insurrection, l’oppression et les conditions de vie des esclaves devinrent plus terribles encore. Leur souffrance inspira des chants de travail et des spirituals visant à élever l’âme qui sont à la racine de nombre de musiques afro-américaines, dont celle de Fats Domino8.

Creole Love Call

La ségrégation raciale était impitoyable et divisait jusqu’aux Afro-américains eux-mêmes9. Néanmoins les francophones à peau claire (qui jouissaient de privilèges) comme de peau foncée s’appelaient eux-mêmes «créoles» pour se distinguer des Africains fraîchement débarqués ou des esclaves en provenance du nord. Les French Creoles parlaient le patois, s’entraidaient, s’efforçaient de préserver leur identité afro-américaine (musique, langues, religions). Ils ne se mélangeaient pas avec les esclaves anglophones dont les velléités de résistance avaient été brisées par des manipulations psychologiques et des mauvais traitements; Les Créoles francophones étaient à part. Calice et Donatile Domino étaient de fiers Créoles qui élevèrent leurs sept enfants sur la plantation Webre-Streib à Vacherie (une section de l’immense plantation Laura) où Calice était laboureur. Catholiques, ils vivaient sur un continent très majoritairement protestant. Ils travaillaient très dur et produisaient en outre leurs propres fruits et légumes pour subvenir à leur alimentation. La famille nombreuse organisait des fêtes le samedi soir où Gustave, le frère de Calice, dirigeait un orchestre. Toute la famille chantait et participait dans la tradition africaine où la musique est l’expression même de la vie. Le dimanche après la messe, ils faisaient à nouveau la fête, ce qui ne se faisait pas chez les protestants.

Nouvelle-Orléans

Vers 1926, Gustave et Calice, Donatile et leurs enfants se sont installés dans les marais récemment asséchés du Lower Ninth Ward, un quartier noir de la Nouvelle-Orléans où n’existaient encore que des chemins de terre, sans réverbères, ni électricité ni téléphone. En tentant leur chance à la ville, à une heure de route de Vacherie, ils espéraient travailler moins dur. Ils laissèrent derrière eux une grande famille et au moins un siècle d’habitudes familiales. Ils apportèrent au cœur de la Nouvelle-Orléans une culture créole rurale et sa musique particulière, héritée de l’esclavage, riche en chants de travail, nourrie de negro spirituals, de blues rural et de chansons des campagnes comme celle qui inspira The Rooster Song (Bo-Weevil est par ailleurs une chanson évoquant le nom d’un parasite du coton, l’anthonome)10.

Antoine Dominique Domino, Jr. dit Fats Domino naquit le 26 février 1928 au 1937 Jourdan Avenue sur la rive du grand canal Industrial, dans le sud de la neuvième circonscription de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Il restera vivre dans ce quartier pauvre jusqu’à la destruction de sa maison par l’ouragan Katrina, qui faillit lui coûter la vie le 29 août 2005. Antoine Junior était le huitième et dernier enfant d’Antoine Domino dit Calice et de son épouse Donatile (née Gros), une femme noire de petite taille, aux ancêtres haïtiens, dont les cheveux raides trahissaient un métissage indien. Les indiens Choctaws sont les indigènes de la région; des Apaches Lipan, déplacés et réduits en esclavage par les Français, s’étaient en outre mélangés aux Choctaws. Le gamin était un peu timide, solitaire et plutôt mince. Il allait à l’école Macarty sur l’avenue Caffin où il déménagerait pour de bon en 1950, et jouait au baseball avec ses frères sur la digue voisine; admirateur de Joe Louis, il pratiquait la boxe. Comme toute la famille il aimait la musique et chantait le week-end dans les soirées entre voisins où son père jouait du violon, ses frères Aristile et John de la batterie et de la trompette. Le jeune Antoine avait dix ans quand ses parents acquirent un piano d’occasion très usé. C’est son beau-frère le banjoïste Harrison Verrett (mari de sa sœur Philonese) qui lui enseigna les accords et inscrit les notes sur le clavier. L’enfant se passionna aussitôt pour le piano, au point que l’instrument fut installé dans le garage pour qu’il puisse mieux s’y consacrer. La musique devint son obsession. Il s’y plongea totalement, apprenant les chansons entendues à la radio, jouant du boogie sur le piano de l’école pour ses copains. Les artistes noirs radiodiffusés étaient très rares, et il adorait «A Ticket a Tasket» (1938), le premier succès d’Ella Fitzgerald qui passait parfois sur les ondes. Accaparé par le piano, Antoine ne faisait pas ses devoirs, et fut même recalé au catéchisme. À l’âge de dix ans, après seulement quatre ans dans une école élémentaire très pauvre, il arrêta ses études pour travailler et devint l’assistant d’un livreur de glace (il n’y avait ni électricité ni réfrigérateurs dans le quartier). Palefrenier dans une écurie, il tondit le gazon de l’hippodrome et de la maison des Blancs où Philonese travaillait comme domestique. Puis ce fut une boulangerie et une usine de café. En ces temps incertains Antoine aimait beaucoup manger et adorait les belles voitures.

Boogie Woogie

Il apprit bientôt le difficile et très influent «Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie» (1928) de Clarence «Pinetop» Smith, en quelque sorte le morceau fondateur du rock, entendu sur le juke-boxe du bar voisin de l’atelier de mécanique de son cousin Joe Cousin où il lavait des voitures et aidait aux réparations. C’est aussi là qu’il découvrit le géant Louis Jordan, «Low Down Dog» de Big Joe Turner, les pianistes de boogie Meade Lux Lewis et les pianistes chanteurs Albert Ammons, Amos Milburn (il copiait son style de chant), Charles Brown et Nat «King» Cole, qui ont formé son style.

Au début des années 1940 Antoine et ses frères sont allés voir le spectacle de vaudeville de Big Alma, qui était suivi de plusieurs films. Il ne ratait pas un film des chanteurs de country Gene Autry et Roy Rogers qui marqueraient son style pour toujours — un métissage qui contribuerait à son succès. Mais les spectacles étaient chers et Antoine se produisait surtout dans les fêtes de famille avec ses beaux-frères Harrison Verrett à la guitare et Stevens à la batterie. Philomena, une autre de ses sœurs, avait transformé le garage en bar et vendait de la bière aux participants — le premier public du futur Fats Domino. Verrett l’emmena travailler en Californie, puis à l’un de ses concerts avec le Tuxedo Jazz Band (avec Oscar «Papa» Celestin) où il le présenta au patron du restaurant The Court of Two Sisters dans le quartier français. En quelques minutes, son boogie au piano lui rapporta huit ou neuf dollars et il décida de devenir professionnel. En 1946 le jeune homme forma un duo avec le saxophoniste ténor Robert «Buddy» Hagans, un adepte d’Illinois Jacquet, Gene Ammons, Chu Berry, Coleman Hawkins et de la grande idole noire de la Louisiane, Louis Armstrong. Ils furent rejoints par le batteur Victor Leonard et le guitariste Rupert Robertson. Après quelques bars, un premier avant-goût de célébrité vint à l’été 1947 quand Paul Gayten, la nouvelle star locale du blues, invita l’adolescent à jouer son morceau de bravoure, le difficile «Swanee River Boogie» d’Albert Ammons où il brillait au piano (il le gravera plus tard sous le nom de Swanee River Hop). Domino joua son premier grand concert dans l’orchestre de Billy Diamond au Rockfort Pavilion peu après avec Harrison Verrett à la guitare. Rosemary Hall, dix-sept ans, a enfin accepté de venir applaudir le pianiste. Ils se marièrent peu après le 6 août 1947 chez les parents de Rosemary (chez qui Fats s’installa), devant le révérend Harzell de l’African Methodist Episcopal Church, le premier temple afro-américain, fondée en 1816 en signe de protestation contre l’esclavage et les discriminations envers les Noirs. Domino aimait la vie de famille et ne quittera jamais Rosemary. Peu après il trouva un travail dans une fabrique de lits où il posait les sommiers sur les montants; Buddy Hagans y fabriquait les ressorts.

Rock and Roll

Le pianiste rencontra alors Dave Bartholomew, un ambitieux trompettiste de jazz «swing» devenu chanteur, compositeur, arrangeur et directeur d’une formation orientée vers ce que l’on appelait alors le blues — et, quand joué à un tempo plus rapide, le jump blues apprécié par les danseurs acrobatiques du lindy hop11. Mais selon leur définition musicologique, ces musiques étaient déjà ce que l’on appellerait bientôt du rock and roll, un genre dynamique plébiscité par les jeunes danseurs des circuits noirs. À cette époque où le jazz moderne de Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk et Charlie Parker surgissait avec une sophistication et une ambition artistique inédites, de plus en plus de formations de swing démodées — comme celle de Bartholomew — se tournaient vers ce blues accéléré, très dansant, simple et efficace. La guitare électrique, un instrument encore nouveau, apportait un vent de fraîcheur au son vents-piano des formations de jazz traditionnelles12. En 1947 dans le magazine Billboard les musiques noires étaient toujours classées à part, sans distinction de style, sous le titre de «Race Records» : un terme ouvertement raciste dans un contexte de ségrégation raciale radicale, imposée par la loi et une répression sans pitié13. Les premiers disques de rock venaient des studios de Californie et incluaient «Rock Woogie» (Jim Wynn’s Bobalibans, 1945), «Rockin’ the House» (Memphis Slim and the House Rockers, 1946), «We’re Gonna Rock», «Rock and Roll» (Wild Bill Moore, 1947 et 1948). Notre coffret Race Records, Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) replace ces essentiels titres oubliés dans leur contexte et retrace en détail l’histoire de cette période où les artistes afro-américains passaient encore très rarement à la radio : ils se faisaient connaître par des concerts dans le chitlin’ circuit noir et les juke-boxes des ghettos14.

1947 fut l’année où la première émission de radio diffusant de la musique noire à la Nouvelle-Orléans, The Poppa Stoppa Show, apparut sur WMJR (avec un animateur blanc formé au «jive» et encadré par le disc jockey noir Vernon Winslow). Calquant sa programmation sur les disques les plus populaires entendus dans les juke-boxes des établissements noirs, Winslow décupla le succès de «Good Rockin’ Tonight», un morceau à la gloire de la fête et du sexe interprété par Roy Brown, un natif de la Nouvelle-Orléans qui avait débuté en chantant du gospel. Avec ce titre essentiel, un concentré de la tradition de la ville, l’histoire du rock tenait son premier hymne. Il fallait faire vite : la radio permettait maintenant de promouvoir le rock qui, après avoir été étiqueté «jump blues» un temps, commençait à être présenté sous la nouvelle étiquette «rhythm and blues». L’orchestre de Dave Bartholomew avait un son original, d’actualité; il était déjà l’archétype et le modèle à suivre du rock and roll qui se cherchait. Avec le génial Earl Palmer à la batterie sa formation était l’une des meilleures de la ville —surpassant même celle de Paul Gayten. Elle était en train de devenir l’une des plus populaires de la région. C’est contre l’avis de Bartholomew qu’Earl Palmer invita Domino à jouer quelques morceaux pendant la pause de l’orchestre. Le public apprécia le pianiste, mais Palmer a été réprimandé par son patron pour avoir invité le jeune homme sur scène. Ce fut le premier contact entre les trois hommes, qui allaient bientôt devenir ensemble une machine à succès.

Hide Away Blues

L’ouverture du Club Desire nouvellement agrandi eut lieu dans la neuvième circonscription nord avec Dave Bartholomew en tête d’affiche lors du Mardi Gras 1948. Le groupe de Billy Diamond devint ensuite l’orchestre maison et Domino commença à se faire connaître avec lui au Desire. Le 15 mai 1948 Buddy Hagans et Antoine Domino prirent leur carte de membre au syndicat des musiciens noirs de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Cette adhésion payante leur donnait accès aux lieux du centre ville comme le Robin Hood sur Jackson, où ils se produirent en duo à la même affiche qu’Annie Laurie, Paul Gayten et Billy Diamond, qui le présenta sur scène sous le nom de Fats («gras») Domino. Rendu furieux par ce sobriquet péjoratif, le jeune homme faisait déjà quatre-vingts kilos et n’a jamais pu se débarrasser de ce nom disgracieux mais facile à retenir, qui rappelait celui du grand pianiste «stride» Fats Waller. Et puis l’épouse de Fats était experte en cuisine créole française, si spéciale, et il ne cessait de grossir. Fats accompagna même Roy Brown avec le groupe de Diamond, mais perdit cet engagement parce que bien qu’invité à le faire, il avait osé chanter du Roy Brown pendant l’intermède instrumental.

Puis le pianiste fut engagé à jouer — et chanter — tous les week-ends au Hideaway Club, deux rues plus loin. Il forma son propre groupe pour répondre à cette proposition. Mal habillé, proche du peuple, timide, souriant, simple, placide, le talentueux Fats appréciait ce lieu populaire où il donnait toute sa mesure. En quelques semaines, ses reprises virtuoses de «Flying Home», «Swanee River Boogie» et le jeu de scène très dynamique de ses musiciens ont rendu les danseurs extatiques. Fats reprenait la chanson traditionnelle «Junker’s Blues» (un succès de 1941 par Champion Jack Dupree, un pianiste de la Nouvelle-Orléans). Il en fit un rock très dansant qui, une fois les paroles modifiées, deviendrait l’année suivante son premier succès, The Fat Man15.

Au cours de la campagne pour l’élection présidentielle de 1948, le président par intérim Harry Truman (Democrat, gauche américaine) lança une série de mesures contre la ségrégation raciale, notamment dans l’armée, ce qui permit à un grand nombre d’afro-américains de s’inscrire sur les listes électorales dont ils étaient jusque-là évincés par les forces racistes du pays. L’élection de Truman à la présidence le 2 novembre fut fêtée par un concert de charité au profit de la NAACP, organisation «pour la promotion des gens de couleur» de W. E. B. Du Bois, où Roy Brown et Albert Ammons se produirent. Peu après, Louis Jordan annonça qu’il ne jouerait plus dans des salles où les Afro-américains étaient relégués au seul balcon. Il fut suivi par les vedettes Nat «King» Cole et Dizzy Gillespie tandis que des arrestations de dizaines de Noirs avaient lieu à la Nouvelle-Orléans pour non respect de la ségrégation. Louis Armstrong fit la couverture de Time Magazine au Mardi Gras 1949 après que le maire de la Nouvelle-Orléans lui ait publiquement offert une clé géante — les clés de la ville. Alors que Professor Longhair gravait son premier disque, que Mao prenait le pouvoir en Chine et que commençait la guerre de Corée repoussant les communistes venus du nord, beaucoup de choses commençaient à changer : le milieu du XXe siècle était là.

Imperial Records

En mai 1949, Vernon Winslow devint le premier animateur de radio noir de la ville sur WWEZ. Il était capable de créer des succès régionaux en quelques jours. L’influence de Roy Brown touchait toute la Louisiane. En juin, les classements de musiques «noires» changèrent d’étiquette. Les «race records» disparurent : ils seraient désormais classés sur une page «R&B», acronyme de «rhythm and blues», le nouveau nom (tout aussi raciste) de la musique populaire noire. Un an ou deux plus tard, ce sont les premiers disc jockeys du nord à diffuser ces musiques du sud à la radio qui estimeront que les termes «race records» et «R&B» étaient trop racistes. Ils leur préfèreraient bientôt le nom de «rock ‘n’ roll», et ce en dépit de la connotation ouvertement sexuelle du terme «rock». Le DJ Blanc Duke «Poppa Stoppa» Thiele continuait son émission «R&B» sans le Noir Winslow, viré parce qu’il avait osé dire un mot à l’antenne. Des musiciens de toute la ville affluaient pour découvrir Fats, qui bondait le Hideaway et faisait sensation. Fin novembre 1949, c’est Dave Bartholomew en personne qui entra au Hideaway pour découvrir le spectacle bien rodé de Fats Domino. Il était accompagné de Lew Chudd (né Louis Chudnofsky), un homme d’affaires blanc né de parents juifs qui avaient fui la Russie tsariste. Chudd avait été naturalisé américain six ans plus tôt. Fondateur des disques Imperial, producteur osant financer des musiques latines et d’autres musiques du monde, il comprenait à la fois l’importance, la qualité et le potentiel commercial des musiques afro-américaines, qui étaient encore largement discriminées et négligées. Comme tant de producteurs juifs à cette époque, il n’avait pas (ou moins) de préjugés racistes (elle aussi victime de discrimination, la petite minorité juive vivait souvent dans les quartiers populaires peuplés par des Noirs). Un nombre significatif de Juifs investissait dans les cruciales musiques afro-américaines que Chudd appréciait, parmi lesquels Alfred Lion (Blue Note), les frères Bihari (Meteor, Modern, Crown), Art Rupe (Specialty) et à la Nouvelle-Orléans les frères Braun (De Luxe, qui publiaient les succès de Roy Brown).

Lew Chudd arrivait tout droit de son bureau d’Hollywood. Homme de radio, attaché de presse et agent d’orchestres de swing, il avait engagé Dave Bartholomew en 1947 pour repérer les nouveaux talents de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Comme Louis Armstrong, Bartholomew avait étudié la trompette avec Peter Davis. Sa famille était originaire d’Edgard, dans la région des plantations, pas loin de Vacherie d’où les Domino étaient venus. Bien qu’issu d’une famille pauvre, il avait appris à écrire la musique à l’armée et avait déjà derrière lui une belle carrière. Bartholomew avait obtenu un gros succès «R&B», «Country Boy», et avait un style d’arrangement de vents bien à lui. Il réalisa sa première séance d’enregistrement pour Lew Chudd/Imperial dans le seul studio de la ville, J&M. Le patron de J&M était lui aussi issu d’une minorité. D’origine italienne, le jeune Cosimo Matassa, dix neuf ans, vendait du matériel électrique, des disques, et avait installé un minuscule studio à gravure directe sur disque en acétate dans son arrière boutique. Le DJ Duke Thiele invita Chudd et Bartholomew au Hideaway pour y découvrir le pianiste de «boogie» qui bondait la salle. Quand Fats Domino joua son grand succès «Junker’s Blues», Chudd lui proposa un contrat sur le champ. Bartholomew lui proposa d’en réécrire les paroles : The Fat Man était le titre d’un feuilleton radio populaire (basé sur une nouvelle de Dashiell Hammett) - et le surnom de Fats. La chanson revisitée fait allusion aux créoles, descendants des métissages du temps des Français et, prophétiquement, au seul quartier de la ville où Noirs et Blancs se mélangeaient. Le 10 décembre, ils gravaient le morceau avec Earl Palmer à la batterie, Frank Fields à la basse, Ernest McLean à la guitare — et les vents dirigés par Bartholomew. Une semaine plus tôt, le président Truman avait interdit la discrimination raciale dans l’attribution des logements publics.

Rockin’ Chair

Lew Chudd demanda à ce que le disque — au son trop brut — soit réenregistré. Mais son associé Al Young avait déjà apporté des acétates aux DJ (Thiele et Winslow) des radios. The Fat Man fut un succès instantané et Chudd dut aussitôt en fabriquer des milliers d’exemplaires. Au cours des fêtes de Noël 1949, toute la ville entendit des gravures en acétate de la chanson à la radio. Avec son premier chèque d’Imperial, Fats s’est offert un modeste piano droit. Au printemps il fut contraint d’accepter une tournée du sud. Les conditions étaient très dures; la ségrégation, la promiscuité, la pauvreté et la faim y régnaient. Il emportait avec lui une valise pleine de victuailles car tout était fermé la nuit. Ils étaient inconnus et eurent peu de succès mais The Fat Man était connu à San Francisco et la foule leur fit un triomphe inattendu. À leur retour, la chanson avait conquis un nombre énorme de gens, de la Californie à New York et jusqu’en Jamaïque où les premiers sound systems diffuseraient bientôt son premier shuffle Little Bee : son Barrel House et d’autres titres américains sur ce même rythme ont contribué à former le goût des danseurs de toute l’île, annonçant le ska de la décennie suivante16. La première station de radio 100% noire de la Nouvelle-Orléans, WMRY, ouvrit en mai 1950. Elle promouvait aussi les autres productions de Bartholomew, qui enregistra bientôt Big Joe Turner et Lloyd Price, Shirley and Lee17… des titres légendaires et influents comme «Rocket 88» (au même riff de vents que «Fat Man») et «Lawdy Miss Clawdy» (avec Fats au piano) étaient influencés par The Fat Man et devinrent d’autres classiques du rock (encore étiqueté «rhythm and blues») après ceux de Domino. Ce qui donne le ton de ce qui suivit. Après la sortie de Little Bee, aux paroles trop suggestives pour la radio, Fats Domino forma un groupe autour de son saxophoniste Buddy Hagans (voir discographie) et le jeune héroïnomane Papoose Nelson (le guitariste de Professor Longhair, qui était aussi prof de guitare du futur Dr. John). Fats devint la tête d’affiche du club Desire et acheta la maison du 1723 Caffin Avenue. Il s’offrit une bague de diamant qui lui coûta tout son argent. Les succès et les tournées (avec Professor Longhair, Lee Allen, Bartholomew…) se multiplièrent et il signa un nouveau contrat avec Imperial en 1951. Sa revanche sur la pauvreté était en marche. Il avait deux enfants, bientôt trois, et une Studebaker Champion neuve. Mal payé, Dave Bartholomew quitta Imperial fin 1950 et Fats enregistra son premier énorme succès national sans lui, Rockin’ Chair, avec en face B un autre succès, Careless Love, qui annonçait l’arrangement original du futur Blueberry Hill. Fats prit pour avocat Charles Levy, Jr., qui devint son fondé de pouvoirs et pourrait signer les contrats à sa place pendant trente ans. Il acquit alors sa première Cadillac noire. Bill Haley, un chanteur de country blanc de Philadelphie, avait enregistré en juin 1951 son premier rock, une reprise de Jackie Brenston («Rocket 88»), mais sans succès. En avril 1952, il recommença avec une reprise d’un autre titre noir, «Rock the Joint», qui se vendit un peu et contribua à orienter son style vers le rock18.

Rock ‘n’ Roll

Le rock ‘n’ roll rabaisse le Blanc au niveau du Nègre.

— Asa Carter, animateur de radio, politicien, fondateur de The North Alabama White Citizen’s Council et fondateur d’une cellule du Ku Klux Klan.

Dans le nord du pays, des DJ blancs clés, dont Bill Randle et Alan Freed, deux rebelles antiracistes basés à Cleveland, suivaient maintenant leurs collègues du sud comme Gene Nobles à Nashville ou Poppa Stoppa à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Le terme «rock ‘n’ roll» était maintenant de plus en plus largement utilisé par les disc jockeys du nord. En mai 1952, de retour dans sa ville après une tournée, Fats subit une émeute qui fit des dizaines de blessés lors d’un grand concert de bienvenue. En juin, malgré un son laissant à désirer et des imperfections (le saxophone est faux !), Goin’ Home fut son premier numéro un «R&B» et un rare succès noir dans les classements blancs «pop». Les efforts promotionnels de l’intrépide Lew Chudd (qui harcelait les radios) payaient au-delà de leurs espérances.

D’autres succès suivirent, chaque fois d’une meilleure qualité — et toujours plus gros. Dave Bartholomew était revenu, cette fois salarié par Imperial et cosignait tous les morceaux. Il s’occupa désormais de tout mettre en forme tandis que Fats proposait le plus souvent la base des chansons : simples, touchantes, ancrées dans la réalité, évoquant des sentiments partagés par tous. Fats Domino était devenu un phénomène. Sa popularité dépassait celle des rares vedettes noires de son temps qui étaient parvenues à passer la barrière raciale et placer quelques disques dans les classements «pop» : Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Jordan, Nat «King» Cole… mais en dépit de cette gloire inespérée, la ségrégation forçait toujours l’équipe à cuisiner dans leurs chambres misérables en tournée. Lors d’un concert dans le nord, le chanteur de première partie Jimmy Gilchrist mourut d’une dose trop forte d’héroïne (remplacé un temps par Screamin’ Jay Hawkins) tandis que le guitariste Papoose était arrêté pour détention d’héroïne. Fats, lui, abusait de l’alcool (légal) mais d’aucun produit illégal.

En 1953 leur musique inspirait des aspirants rockers comme Buddy Holly, Bobby Charles, Frogman Henry (qui a basé son «Ain’t Got No Home» sur les «woo woo woo woo» de Please Don’t Leave Me19) et Little Richard20. Après plus de deux millions de disques vendus, Fats signa pour neuf ans de plus avec Imperial. Il faudrait encore un an pour qu’Alan Freed refuse de parler de «R&B» ou de «rhythm and blues» à la radio et préfère utiliser systématiquement le terme «rock ‘n’ roll». En 1954 Fats Domino était devenu l’incontestée vedette noire numéro un du pays — mais ses meilleurs et plus énormes succès étaient à venir, comme le montre le remarquable disque n°4 de ce coffret (1955-1957). Son style de rock et de chanson populaire étaient imprégnés d’accents blues dans le chant comme dans les instruments. Les arrangements de Bartholomew étaient copiés un peu partout ; Tout en renouvelant la tradition des instruments à vent de la période swing/jump blues/rhythm and blues, Fats Domino et son équipe avaient, les premiers, défini, gravé dans le marbre et rendu célèbre pour l’éternité le son de la nouvelle musique rock. En 1955 Little Richard leur emprunta leur son, leur style, musiciens et studio avec succès. En 1955-1957 une chanson à succès sur deux avait le son du nouveau studio de Cosimo Matassa, le son de la Nouvelle-Orléans — le son de Fats Domino, qui avait défini le son du rock ‘n’ roll.

Ray Charles, Clyde McPhatter, Little Richard et même son héros de jeunesse Charles Brown tournèrent en première partie de Fats. À partir de 1955 un nombre très important de jeunes blancs affluait aux concerts sans hésiter. Ils défiaient leurs parents, qui approuvaient souvent la ségrégation. Fats Domino dominait le marché du rock et plus que tout autre jusque là, faisait reculer la ségrégation raciale. Il chantait maintenant dans des salles «blanches» en plus des autres. La corde séparant les publics noir et blanc dans les salles était parfois physiquement piétinées, réunissant les jeunes sans discrimination et déchaînant la répression policière. Ses dizaines de succès figuraient parfois dans les classements «pop» — c’est à dire blancs — en plus des meilleures ventes «R&B». Des artistes blancs comme Pat Boone, Ricky Nelson, The Fontana Sisters, Bill Haley, Teresa Brewer ou Gale Storm obtinrent une ribambelle de succès «pop» bien plus importants que les siens en reprenant ses compositions (ce qui était un symbole de discrimination), souvent de façon édulcorée. Les droits d’auteur revenaient en partie à Domino et Bartholomew. La tendance était à donner la nouvelle étiquette vendeuse de «rock ‘n’ roll» aux Blancs qui copiaient le «rhythm and blues», et à réserver cette appellation «R&B» racialement connotée aux seuls Noirs. Mais la ségrégation raciale commençait à chanceler. Après une longue bataille politique, elle était maintenant déclarée «inconstitutionnelle» dans les écoles. Le succès de Fats était une locomotive. Plus que tout autre artiste noir il contribua avec son succès inter racial à lancer le grand Mouvement des Droits Civiques qui, en décembre 1955 exigea la fin de la ségrégation raciale avec à sa tête Martin Luther King21.

Superstar

Je préférais le temps de la ségrégation. On s’amusait bien plus.

— Dave Bartholomew

«Heartbreak Hotel» et «Blue Suede Shoes» avaient une intro qui rappelait beaucoup celle de Ain’t That a Shame, un succès immense — et la première chanson apprise par John Lennon. L’irruption d’Elvis Presley à l’été 1954 avait apporté au rock un interprète blanc, un séducteur, un roi. Et une couleur musicale différente, teintée de guitares country et de sobriété instrumentale22. Après le succès de «Rock Around the Clock» en 1955, Bill Haley et Elvis furent présentés comme les pionniers du rock alors que des dizaines de chanteurs noirs les avaient précédés, Fats en tête23. Pendant la mode nationale du rock très controversée de 1955 à 1958, et alors qu’Elvis atteint une notoriété invraisemblable en 1956, le succès de Fats Domino redoubla. Il resta au sommet des ventes R&B du printemps 1956 à l’été 1957 et deviendrait le n°2 des champions des ventes de la décennie, juste derrière son ami, concurrent et soutien Elvis Presley. En mars, il avait pas moins quatre titres dans le Top 100 du Billboard, un record.

Les péripéties liées à sa condition de superstar du rock ne lui ont pas été épargnées : émeutes à répétition, bagarres générales, concerts à guichets fermés, scandales, répression, drogues dans son entourage, alcoolisme, groupies, hystérie médiatique, provocations racistes, intimidations mais aussi disques d’or, popularité, pluie de dollars qui fait perdre la tête, succès en Angleterre, télévision à l’Ed Sullivan Show (avec ses musiciens cachés derrière un rideau car noirs), sans oublier le film The Girl Can’t Help It… à Houston la police voulut interdire aux Noirs de danser : Fats refusa de continuer à jouer et la police arrêta le spectacle. Dans la plupart des villes du sud, dont la Nouvelle-Orléans, les concerts integrated où des artistes noirs et blancs alternaient restaient strictement interdits.

À la fin de l’été 1957 Fats Domino avait vendu vingt-cinq millions de disques dont le chef-d’œuvre Blue Monday et ses chansons étaient écoutées dans le monde entier. Son influence reste incalculable. Les plus grands noms de la décennie suivante adoraient sa musique. Pour les Noirs, son exemple était une véritable catharsis. Alors qu’en 1958 Elvis allait disparaître à l’armée puis sur les plateaux de cinéma d’Hollywood, Fats Domino fut aussi l’un des rares à résister à l’offensive américaine anti-rock de 1957-1962 avec des morceaux vigoureux comme I’m Walkin’, Don’t You Know I Love You, Lazy Woman, Whole Lotta Loving, I’m Ready, Shu Rah, Ain’t That Just Like a Woman, Ain’t Gonna Do It ou Be my Guest — tous des succès rock substantiels. Néanmoins comme tous les artistes de la fin des années 1950, il n’a pas pu battre la vague conservatrice qui considérait la popularité du rock subversive24. Tout en continuant dans la veine rock, il avait dès 1955 enregistré le vieux succès My Blue Heaven à la suggestion des disques Imperial, qui voulaient toucher les vieux en plus des jeunes — et plaire au grand public blanc. Dès cette période, Domino, qui appelait sa femme tous les jours, arrivait de plus en plus en retard aux concerts (quand il ne refusait pas de venir) et ne supportait plus la vie harassante sur la route (340 jours par an). Comme plusieurs chansons le suggèrent, il rêvait de rentrer vivre avec ses six enfants. Il fut encouragé à enregistrer d’autres chansons de variété, aux arrangements chargés, parfois même avec des violons. Déjà gravée par Louis Armstrong, sa splendide reprise de Blueberry Hill fut son plus gigantesque succès «pop» jusqu’en Europe, et jusque dans les classements «country». Ses titres les plus «commerciaux», qui ne se vendaient pas bien et furent vite oubliés, n’ont pas effacé les énormes succès de grande qualité qui ont nourri la musique populaire américaine et du monde jusqu’à la fin de son contrat avec Imperial en 1962 — quand les Beatles ont pris le relais.

Bruno Blum, septembre 2016.

Merci à Rick Coleman, Stéphane Colin et Baptiste Manet.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2017

1. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA 5465) dans cette collection.

2. Lire les livrets et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine, volume 1 1954-1956 (FA 5361) et vol. 2 1956-1957 (FA 5607) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter New Orleans Roots of Soul 1941- 1962 (FA 5633) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter Voodoo in America 1926-1961 (FA 5375) dans cette collection.

6. Lire la biographie de Rick Coleman Blue Monday - Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock ‘n’ Roll (Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Massachusets, 2006).

7. Lire les livrets et écouter Haiti Vodou - Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (FA 5626) et Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972-Musiques issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques (FA 5467) en coédition avec le musée du Quai Branly dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret et écouter The Color Line 1916-1962 Les artistes africains-américains et la ségrégation raciale (FA 5654) en coédition avec le musée du Quai Branly dans cette collection.

10. Bo-Weevil ne doit pas être confondu avec «Boll Weevil», une chanson traditionnelle dont un enregistrement est inclus sur The Indispensable Eddie Cochran 1955-1960 (FA 5425) dans cette collection.

11. Écouter Dave Bartholomew chanter son remarquable «Another Mule» sur New Orleans Roots of Soul 1941-1962 (FA 5633) dans cette collection.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Electric Guitar Story 1935-1962 (FA 5421) dans cette collection.

13. Lire le livret et écouter The Color Line, Les artistes africains-américains et la ségrégation 1916-1962 (FA 5654) en coédition avec le musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac dans cette collection.

14. Race Records contient un titre de Fats Domino de 1951, No No Baby.

15. La version à succès de «Junker’s Blues» enregistrée en 1941 par Champion Jack Dupree est disponible sur New Orleans Roots of Soul 1941-1962 (FA 5633) dans cette collection.

16. Lire le livret et écouter d’autres titres aux racines du ska dans Roots of Ska - USA Jamaica 1942-1962 (FA 5396) dans cette collection.

17. Produits par Bartholomew, les premiers succès de Shirley and Lee et Lloyd Price sont disponibles sur New Orleans Roots of Soul 1941-1962 (FA 5633) dans cette collection.

18. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Bill Haley 1948-1961 (FA 5465) dans cette collection.

19. «Ain’t Got No Home» par Clarence «Frogman» Henry est disponible dans New Orleans Roots of Soul 1941-1962 (FA 5633) dans cette collection.

20. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607) dans cette collection.

21. Lire le livret et écouter Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 Musiques issues de l’esclavage aux Amériques (FA 5467) et The Color Line 1916-1962 Les artistes africains-américains et la ségrégation raciale (FA 5654) en coédition avec le musée du Quai Branly dans cette collection.

22. Lire le livret et écouter Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA 5423) dans cette collection.

23. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique populaire américaine vol. 1 1954-1956 (FA5361) dans cette collection.

24. Lire le livret et écouter Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique populaire américaine vol. 2 1956-1957 (FA 5383) dans cette collection.

The Indispensable Fats Domino 1949-1962

by Bruno Blum

There are no precursors, only latecomers.

— Jean Cocteau

Fats Domino was no less than the first true rock superstar — years before Little Richard, Bill Haley1 and Elvis Presley2.

A lot of people seem to think that I started this business. But rock ‘n’ roll was here a long time before I came along… Let’s face it: I can’t sing like Fats Domino can. I know that. — Elvis Presley

Fats Domino was one of the biggest record sellers of the 1950s. To the point that some of his enormous hit records, such as Blueberry Hill or I’m Walkin’ overshadowed much of his impressive, wide-ranging discography. Who can remember his virtuoso boogie woogie piano, his heartfelt blues, his charming, candid balads or his fast tempo rock? In a severe racial segregation context, he was by far the most famous black artist of the original rock ‘n’ roll years, way more popular than Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

From as early as 1950, his twelve years with Imperial Records made possible the unimaginable triumph of the original, authentic rock music. In his own natural, simple and kind way, this consensual artist was able to alternate blues and old pop songs, as well as create a vigorous rock output that made a whole generation hum and dance. In partnership with his producer and arranger, Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino seduced America, using his eternal smile and his happy songs, which were full of bold, efficient rhymes. In turn, Little Richard covered his songs and soon borrowed his team, with whom he recorded a series of great, essential hit records3.

He was everything to me. I felt honored just to shake his hand. I still feel that way about Fats Domino.

— Little Richard

A modest, good-natured man and the father of a large family, with the help of some of New Orleans’ best musicians Fats Domino created a very influential musical style that left a deep mark on Little Richard, Elvis Presley, as well as The Beatles, soul artists and Jamaican reggae musicians (his 1960 upbeat piano rhythm on It Keeps Rainin’ was an odd forewarning of reggae music). A solid, original piano player, he made the best out of his influential, trademark triplets and his own rhythms.

This sincere, charming, soft-voiced singer and down-to-earth man came from a large, poor family. It was quite natural that he should accomplish the synthesis of New Orleans’ afro-caribbean and Creole legacy — the source of much of the twentieth century’s popular music4. The brilliant Fats Domino was able to propel his French Creole heritage to the top and appeal to a wide, white audience, as had done a quarter of a century earlier the great pioneer of integration Louis Armstrong — who was also from New Orleans.

Under the pressure of stardom, and after seven years of a prolific and lucrative golden age, from 1957 he was driven to record more and more commercial songs that took him away from his true style — all of these recordings were put aside here —, which heralded his fall. Following more than fifty huge blues and rock hits in his country, Fats Domino, the popular hero of a generation almost sank into oblivion after his last sessions for Imperial in 1962. This set showcases his best recordings, including many overlooked tunes which his big hits eclipsed. They were selected out of more than two hundred titles cut for Imperial, mostly with Dave Bartholomew and his team. As Domino increasingly detested touring, the singer eventually refused to leave his city (even staying away from a show at the White House) and lived for the rest of his life as a family man in a nice house he had built in his working class neighbourhood, which he never left — and where he cruised around in his pink Cadillac Eldorado.

Vacherie

Several generations of the Domino family had lived and worked as slaves on the immense Vacherie sugarcane plantations by the Mississippi’s edge, some thirty miles outside the city. The earliest Domino traced back to the area was also named Antoine, a mulatto born in Vacherie in 1824. It is likely that he was a member of an already substantial family. Émeline, the mother of Carmelite (Fats Domino’s grandmother), was separated from her husband, and sold in 1860. Carmelite lived as a house servant on the Gold Star plantation where she bore four children, the last of which was Fats Domino’s father. She was a respected midwife, a herbal medicine expert and an animist priestess in the local hoodoo tradition, which pervades the culture and music of Louisiana5. Before she deceased in 1944, the old lady had been able to enjoy her grandson’s skills at the piano. But, being the daughter of a slave, she could never have imagined what was to follow6.

It was back in 1682 that explorer René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle gave Louisiana its name, as a tribute to Louis XIV, the King of France at that time. France sold Louisiana to Spain at the Paris treaty in 1763 (it was later returned to France in 1800, then sold to the United States in 1803), but the French language endured through French colonists and their slaves, which were isolated from the rest of the world anyway. This was the case on the gigantic Laura plantation in Vacherie. Around 1800, as a result of the Haitian revolution, many French-speaking planters moved to Louisiana with thousands of slaves. In 1811, five hundred haitian slaves rose up and were massacred. Some managed to join maroon camps and a few found freedom. As did many Cuban slaves exiled in New Orleans, they had a big input on Louisiana’s afro-caribbean identity, as evidenced on titles such as Mardi-Gras in New Orleans or Don’t You Hear Me Calling You7. Following this insurrection, the situation and oppression of slaves got even harsher. Their sufferings inspired many work songs and spirituals aiming to uplift the soul, all of which lay at the root of so many African-American musics, including Fats Domino’s8.

Creole Love Call

Racial segregation was merciless, and it divided even African-Americans9. However, the French-speaking light skinned (who enjoyed some privileges) as well as the dark skinned all called themselves creoles to differentiate themselves from recently disembarked Africans, or slaves deported from the North. French Creoles spoke patois, helped each other, and strived to maintain their African-American identity through music, language and religion. They did not mix with English-speaking slaves, whose resistance leanings had been broken by psychological manipulation and mistreatment. The French Creoles set themselves apart.

Calice and Donatile Domino were proud Creoles who raised seven children on the Webre-Streib plantation in Vacherie (which was a section of the huge Laura plantation), where Calice worked as a ploughman. They were Catholics in a vastly protestant land. They worked very hard and, on top of that, grew their own fruits and vegetables to sustain themselves. The large family partied on Saturday nights, when Calice’s brother, Gustave, lead a band. The whole family joined in and sang in the spirit of African tradition, where music is the very expression of life. On Sundays, after Mass, they partied again, which protestants would not do.

New Orleans

Around 1926, Gustave and Calice, Donatile and their children moved to the latest drained-out swamps that became the Lower Ninth Ward, a black New Orleans neighbourhood linked only by muddy paths, with no street lights, electricity or telephone.

Hoping to work less hard, they tried their luck in the city, about an hour away from Vacherie. They left a large family behind, and at least one century of family customs. They brought to the heart of New Orleans a rural, Creole culture and its particular music, which was inherited from the days of slavery and nourished with work songs, negro spirituals, country blues and country songs, like the one that inspired The Rooster Song (and Bo-Weevil is a song alluding to a cotton parasite insect)10.

Antoine Dominique Domino, Jr. aka Fats Domino was born on February 26,1928 at 1937 Jourdan Avenue, on the edge of the great Industrial Canal, in the Southern part of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. He would live all of his life in this poor area, until hurricane Katrina destroyed his house and nearly drowned him on August 29, 2005. Antoine Junior was the eighth and last child of Antoine Domino, aka Calice, and his spouse Donatile (née Gros), a petite black woman of Haitian descent. Her straight hair gave her part-Indian blood away. Choctaw Indians were indigenous to the area; Lipan Apaches were displaced and made slaves by the French, and they mixed with Choctaws.

The boy was a bit shy, solitary and rather slim. He went to Macarty School on Caffin Avenue, where he would move for good in 1950, and played baseball with his brothers on the nearby levee. He admired Joe Louis and practiced boxing. He liked music, just as all of his family did, and sang at evening parties, where his father played the violin and his brothers, Aristile and John, played drums and trumpet.

The young Antoine was ten when his parents bought an old, beat-up piano. His brother-in-law, banjoist Harrison Verrett (who’d married his sister Philonese) taught him chords and wrote down the notes on the keys. The child got so passionate about the piano that the instrument was moved to the garage so that he could better devote himself to it. Music became his obsession. He buried himself in it, learning tunes heard over the radio, and playing some boogie woogie on the school’s piano for his mates. Black music was seldom heard on the radio, and he loved “A Ticket a Tasket” (1938), Ella Fitzgerald’s first hit record, which sometimes made it to the airwaves. Monopolised by his piano, Antoine did not do his homework, and even failed at Sunday school. After only four years in a very poor elementary school, he dropped out and became the assistant of an ice delivery man (there was no electricity or fridges around in those days). He then groomed horses, mowed the whole Hippodrome and the white people’s lawn where his sister Philonese worked as a servant. Next he worked in a bakery and a coffee factory. In those unpredictable days, Antoine loved eating and was very fond of fancy cars.

Boogie Woogie

He soon learnt Clarence “Pinetop” Smith’s difficult and very influential “Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie” (1928), which was pretty much rock’s founding number. He heard it on the juke-box in the bar next door to his cousin Joe Cousin’s mechanic’s workshop, where he washed cars and helped in repairing them. This is also where he first heard the giant Louis Jordan, Big Joe Turner’s “Low Down Dog,” boogie pianist Meade Lux Lewis and singer-piano players Albert Ammons, Amos Milburn (he also copied Milburn’s singing style), Charles Brown and Nat “King” Cole, who all helped to shape his music.

In the early 1940s Antoine and his brothers went to see Big Alma’s vaudeville show, which was followed by several films. He never missed films with country music singers Gene Autry and Roy Rodgers, which forever left a deep mark on his style — a mix that would later contribute to his success. But shows were expensive and Antoine mostly performed in family parties with his brothers-in-law Stevens on the drums and Harrison Verrett on the guitar. Philomena — another of his sisters — had transformed the garage into a bar and sold beer to participants — Fats Domino’s first audience. Verrett took him to work in California, then to one of his own gigs backing Oscar “Papa” Celestin in the Tuxedo Jazz Band. This is where he introduced him to the owner of The Court of Two Sisters restaurant in the French Quarter. Domino made eight or nine dollars in a few minutes, playing some boogie woogie piano, and decided to go professional.

In 1946 the young man teamed up with tenor saxophone player Robert “Buddy” Hagans, an Illinois Jacquet fan who also loved Gene Ammons, Chu Berry, Coleman Hawkins and Louisiana’s great black idol, Louis Armstrong. They were soon joined by drummer Victor Leonard and guitar player Rupert Robertson. After playing a few joints, an early taste of fame came in 1947 when Paul Gayten, a new local blues star, invited the teenager along to play his best tune, Albert Ammons’ hard-to-play “Swanee River Boogie” (he later cut it under the name Swanee River Hop). Soon, Domino played his first big stage show, in Billy Diamond’s orchestra at Rockfort Pavilion, with Harrison Verrett on the guitar. That is where his seventeen-year-old date, Rosemary Hall, finally agreed to come and applaud him. They married soon after, on August 6, 1947, in Rosemary’s parents home. The ceremony was led by Reverend Harzell of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first African-American church ever founded in the USA, created back in 1816 as a protest against discrimination towards Black people. Domino loved family life and would never leave Rosemary. A little later he found a job in a bed handicraft factory, where he would fit springs onto frames; Buddy Hagans bent and made the springs.

Rock and Roll

The pianist then met Dave Bartholomew, an ambitious “swing” jazz trumpet player turned singer, composer, arranger and bandleader, in what was then called a blues group — a music that, when played at a fast tempo, was then dubbed “jump blues” and favoured by lindy hop dancers11. However, according to strict musicological definition, these musics were already what would soon be called ‘rock and roll’, a dynamic genre loved by young dancers in the black network.

Modern jazz by artists such as Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker was breaking through at the time, displaying sophistication and an artistic ambition unheard of before then. As a result, more and more outdated swing orchestras — such as Bartholomew’s — turned to the more efficient, simple, sped up, danceable blues.

The electric guitar was still quite a new instrument at the time. It updated and brought some freshness to the wind, brass and piano sound of established jazz groups12. In 1947, Billboard magazine still charted black musics on a separate page, with no distinction between styles, under the title “Race Records”. This openly racist term was common in a radical, segregated context enforced by law — and merciless repression13.

The earliest rock records came from California studios and included “Rock Woogie” (Jim Wynn’s Bobalibans, 1945), “Rockin’ the House” (Memphis Slim and the House Rockers, 1946), “We’re Gonna Rock” and “Rock and Roll” (Wild Bill Moore, 1947 and 1948), as compiled on our Race Records, Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio 1942-1955 (FA 5600) set in this series, which displays overlooked, essential recordings back in their context and depicts in detail the history of a time when African-American artists still very rarely obtained airplay: they got well-known through concerts on the chitlin’ circuit and ghetto juke-boxes14.

1947 was the year when the first ever radio show broadcasting black music in New Orleans, The Poppa Stoppa Show, appeared on WMJR (it featured a white speaker coached to speak some jive by a black DJ, Vernon Winslow). Winslow used the top songs heard in black joints’ juke-boxes as a blueprint for his selection, soon multiplying the success of Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” a rocker glorifying parties and sex. Roy Brown was born and raised in New Orleans. He had started his career singing gospel. This essential recording was the epitomy of the Crescent City’s tradition, and rock music now had its first hymn. There was no time to lose: radio could now promote rock music which, after getting sold under the “jump blues” tag for a while, was now catching on as “rhythm and blues.”

Dave Bartholomew’s orchestra had an original, topical sound; it was already the archetype and the model to follow for rock and roll, which was still trying to find itself. Using the genius drummer Earl Palmer, he lead one of the best bands in the city — an even stronger one than Paul Gayten’s. The group was on its way to becoming the most popular in the area. It was against Bartholomew’s advice that Earl Palmer invited Domino to play a few songs during the band’s pause. The audience liked it, but Palmer was told off by his boss for inviting the young man onstage. This was the first encounter between the three men, who would soon become a winning team — a money machine.

Hide Away Blues

The new, refurbished Desire Club’s opening took place in the northern part of the Ninth Ward on Mardi Gras Day, 1948. Dave Bartholomew headlined the show. Billy Diamond’s group soon became the house band and Domino, who backed him, first made himself known there. On May 15, 1948, Buddy Hagans and Antoine Domino payed their fee to join the union for New Orleans Black musicians. Their membership allowed them to play downtown clubs such as The Robin Hood on Jackson, where they played a duet on the same bill as Annie Laurie, Paul Gayten and Billy Diamond, who introduced him as “Fats” Domino.

This infuriated the young man, who already weighed a hundred and sixty pounds, but he could never get rid of this ungraceful, easy to remember nickname that reminded people of Fats Waller, the great stride piano master. Also Fats’ spouse was an expert in cooking the fine, special, Creole cuisine, and he kept putting on weight. Fats even backed Roy Brown in Diamond’s band but he lost the gig because, although he was asked to do so, he dared to sing a Roy Brown song during the instrumental pause.

This is when the pianist was invited to play — and sing — every weekend at the Hideaway Club, a couple of blocks up the road. He immediately formed a band to fulfil this demand. Dressed like a scarecrow, close to the people, shy, ever smiling, the simple, placid and talented Fats appreciated this popular club where he could realise his full potential. In a few weeks, his virtuoso renditions of “Flying Home,” “Swanee River Boogie” and his musicians’ very dynamic stage act drove the dancers ecstatic. Fats covered the traditional song “Junker’s Blues”, a 1941 hit record by New Orleans pianist Champion Jack Dupree. He turned it into a very danceable rock song. With modified lyrics, it would eventually become his first hit song the following year, as The Fat Man15.

During the 1948 presidential election campaign, interim Democrat president Harry Truman launched a series of measures against racial segregation, most notably in the U.S. Army. This enabled a great number of African-Americans to register to vote, which had been so far nearly impossible for them, as they had been viciously excluded from their right to vote by the racist forces of the country. Truman’s election as President, on November 2nd, was celebrated by a benefit show for W. E. B. Du Bois’ organisation ‘promoting the people of color,’ The NAACP.

Roy Brown and Albert Ammons played there and a few days later Louis Jordan stated publicly that he would not play any more shows where Black people’s access was limited to the balcony. Celebrities such as Nat “King” Cole and Dizzy Gillespie did the same, as many Blacks were arrested in New Orleans for violation of segregation laws. Louis Armstrong made the cover of Time Magazine on Mardi Gras Day, 1949, after the New Orleans Mayor handed him a giant, symbolic City Key. And, as Professor Longhair recorded his first song, Mao Zedong seized power in China and the Korean war started as Communists invading from the North were repelled. Much was happening as the mid-twentieth century hit its stride.

Imperial Records

In the month of May, 1949, Vernon Winslow became the first black radio speaker in the city. He could turn a local record into a hit in just a few days on his WWEZ show. By then Roy Brown’s influence had reached all of Louisiana. In June, the “Black” music charts changed their name. “Race Records” were replaced by “R&B” (as in ‘rhythm and blues’), a new (just as racist) name for Black popular music. A year or two later, taking into consideration the implicit racist contents of the “Race Records” and “R&B” tags, disc jockeys in the Northern states began using another label. They were among the first to air these Southern Black musics, but started using the term ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ instead — in spite of the sexual overtones implicit in that phrase. White DJ Duke “Poppa Stoppa” Thiele carried on his ‘R&B’ show after his black coach, Winslow, was fired for daring to speak a few words on the air. Musicians were now coming from all around the city to check out Fats, who filled the Hideaway to the rafters and caused a bit of a sensation. In late November, 1949, Dave Bartholomew himself walked in to enjoy Fats’ funky, up and running show.

Also, in walked his partner, Lew Chudd (born Louis Chudnofsky), a white businessman born to Jewish parents who’d fled tsarist Russia. Chudd had become a naturalized American citizen just six years previously. He had founded Imperial Records, and dared to produce latin and world music. He also understood the importance, quality and potential of African-American music, which was still widely discriminated and overlooked. As so many Jewish producers did at the time, he did not have any (or at least, had less) racial prejudice (also the victims of discrimination, the small U. S. Jewish minorities often lived in working-class neighborhoods where Blacks also dwelled). A significant number of Jews were investing in the crucial African-American music Chudd appreciated, including Alfred Lion (Blue Note), the Bihari brothers (Meteor, Modern, Crown), Art Rupe (Specialty) and, in New Orleans, the Braun brothers (De Luxe, who issued Roy Brown’s records).

Lew Chudd came straight from his Hollywood office. A radio man, press officer and swing orchestras’ agent, he had hired Dave Bartholomew as his New Orleans talent scout. Just like Louis Armstrong had done before him, Bartholomew had studied the trumpet with Peter Davis. His family was from Edgard in the plantations area near Vacherie, where the Dominos had come from. Although he had come from a poor family, he had learned to read music in the army and already had a very good career. He had just had a major “R&B” hit named “Country Boy” and possessed a style of wind instrument arrangement that was distinctly his own.

He produced his first recording session for Lew Chudd/Imperial at J&M’s, the only studio in the city. J&M’s boss had also sprung from a minority group. The young Cosimo Matassa (who was nineteen then) was of Italian descent. He sold electrical hardware and records and had built a tiny, acetate, direct-to-disc studio in the back of his shop. DJ Duke Thiele invited Chudd and Bartholomew down to the Hideaway to discover the “boogie” pianist who packed the house. The minute Fats Domino played his big tune, “Junker’s Blues,” Chudd pulled out a contract and offered it to him. Bartholomew offered to help rewrite the lyrics as The Fat Man, which was the name of a popular radio series based on a Dashiell Hammett novel — as well as Fats’ nickname. Once revisited, the song alluded to Creole people, who were descended from mixed-race people back in French colonial times, and, rather prophetically, to the only neighbourhood where Blacks and Whites actually mixed. On December 10th, 1949, they cut the record with Earl Palmer on drums, Frank Fields on bass, Ernest McLean on guitar — and with the wind instruments conducted by Bartholomew. Just a week before, President Truman had outlawed, at least on principle, racial discrimination in public housing awarding.

Rockin’ Chair

Lew Chudd found the sound too rough and asked them to record the song again. But his partner, Al Young, had already taken it to the radio deejays (Thiele and Winslow). The Fat Man was an overnight hit and Chudd had to order thousands of copies right away. Around Christmas, 1949, all of the city could hear acetate dubs of the song played over the radio. With his first royalties check, Fats bought a modest, upright piano.

The following spring he was compelled to tour the South. The conditions were harsh: segregation, promiscuity, poverty and, because every store was closed at night, hunger ruled. So Fats carried a suitcase full of food around. They were virtually unknown and had little success, but The Fat Man had hit a hip San Francisco crowd and they roared — an unexpected triumph for them. By the time they got back, the song had conquered many people, all the way from California to New York - and even Jamaica, where the first sound systems would soon play Fats’ first shuffle tune, Little Bee. Fats’ Barrel House and other records of his with that same shuffle beat contributed to shaping the future taste of Jamaican dance halls.

Along with many other shuffle recordings made in America, they were forerunners of the ska genre, which surfaced in the following decade16. WMRY, the first 100% Black radio station in New Orleans, was born in May, 1950. It promoted Bartholomew’s productions, soon including Big Joe Turner, Lloyd Price and Shirley and Lee17. Legendary and influential songs such as “Rocket 88” (which used the same horn riff as “Fat Man”) and “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” (with Fats on the piano) were influenced by The Fat Man and also became rock classics (at a time when it was still tagged “rhythm and blues”) following Domino’s hit.