- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

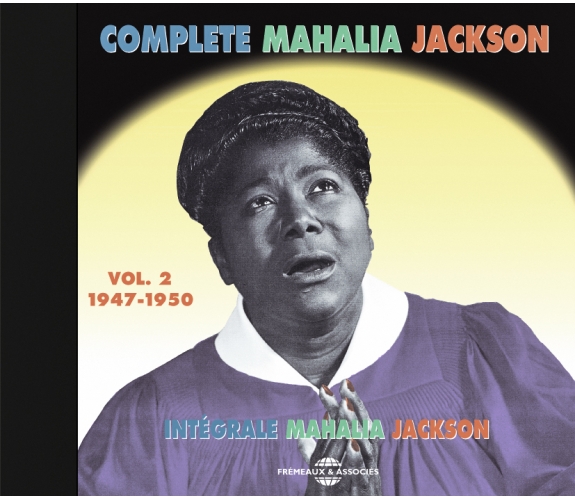

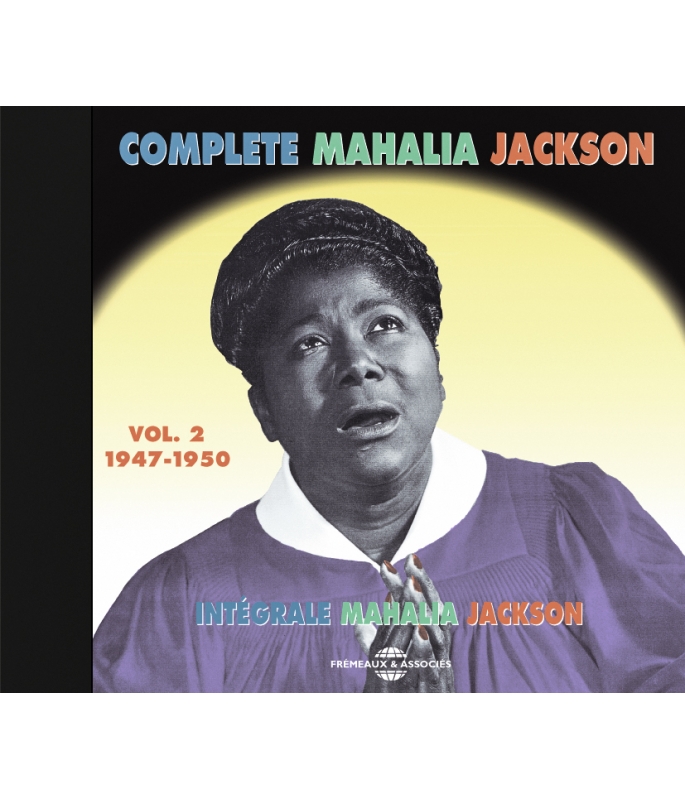

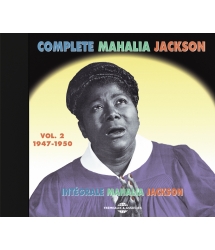

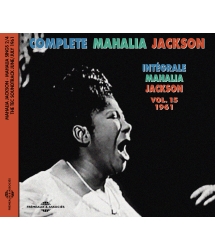

1947-1950

MAHALIA JACKSON

Ref.: FA1312

EAN : 3561302131221

Artistic Direction : JEAN BUZELIN

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 2 minutes

Nbre. CD : 1

1947-1950

1947-1950

“In a world given over to darkness and disorder, the Kingdom of God may still reign in the hearts of men”. Martin LUTHER KING. Includes a 24 page booklet with both French and English notes.

1953-1954

1952-1952

1937-1946

INTEGRALE 1954-1955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1DIG A LITTLE DEEPERMAHALIA JACKSONK MORRIS00:02:591947

-

2THERE S NOT A FRIEND LIKE JESUSMAHALIA JACKSONHUGG00:03:431947

-

3I CAN PUT MY TRUST IN JESUSMAHALIA JACKSONK MORRIS00:03:181949

-

4LET THE POWER OF THE HOLY GHOST FALL ON MEMAHALIA JACKSONMAHALIA JACKSON00:02:201949

-

5CHILD OF A KINGMAHALIA JACKSONSMITH00:03:201949

-

6GET AWAY JORDANMAHALIA JACKSONW MC DADE00:02:401949

-

71 WALK WITH MEMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:511949

-

82 WALK WITH MEMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:441949

-

9PRAYER CHANGES THINGSMAHALIA JACKSONR ANDERSON00:03:111949

-

10SHALL I MEET YOU OVER YONDERMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:501950

-

11THE LAST MILE OF THE WAYMAHALIA JACKSONC A TINDLEY00:02:341950

-

12JUST OVER THE HILL PART I AND IIMAHALIA JACKSONW H BREWSTER00:05:211950

-

13I DO DON T YOUMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:131950

-

14GOD ANSWERS PRAYERSMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:02:191950

-

15I M GLAD SALVATION IS FREEMAHALIA JACKSONBOWLES00:02:551950

-

16DO YOU KNOW HIMMAHALIA JACKSONCHARLIE PARKER00:02:161950

-

17I M GETTING NEARER MY HOMEMAHALIA JACKSONW H BREWSTER00:03:011950

-

18I GAVE UP EVERYTHING TO FOLLOW HIMMAHALIA JACKSONHENDERSON00:03:161950

-

19IT PAYS TO SERVE THE JESUSMAHALIA JACKSONTRADITIONNEL00:03:151950

-

20THESE ARE THEYMAHALIA JACKSONW H BREWSTER00:02:551950

-

21HE S THE ONEMAHALIA JACKSONMATTHEWS00:02:431950

COMPLETE MAHALIA JACKSON Vol.2 FA 1312

COMPLETE MAHALIA JACKSON

Vol.2 1947-1950

INTÉGRALE MAHALIA JACKSON

Lorsque débute l’année 1948, Mahalia Jackson vient d’atteindre d’un coup la célébrité. Du moins auprès de la population de couleur dont elle devient l’une des «idoles», tous genres confondus.Après une ascension longue et difficile accomplie par un travail sur le terrain et qui l’a installé, depuis le début des années 40, parmi les interprètes connus de gospel – tournées avec Thomas A. Dorsey (1), participation annuelle à la National Baptist Convention, etc. – la chanteuse a vu, en l’espace d’un an, son existence se modifier radicalement. Ainsi, malgré leurs ventes médiocres, ses premiers disques Apollo réalisés à l’automne 1946 ont attiré l’attention d’un auteur-comédien-journaliste de Chicago, J. Louis «Studs» Terkel. Ce dernier, qui a été particulièrement frappé par I’m Going To Tell God, son premier disque (Apollo 110), interviewe la chanteuse lors d’un show radio, «The Wax Museum», diffusé sur la station WENR à Chicago. Studs Terkel est un des premiers disk jockeys blancs à programmer, sur une radio de même couleur, des artistes noirs, ce qui en retour va entraîner des auditeurs noirs à se mettre à l’écoute de l’émission. Terkel présente ainsi Mahalia Jackson : «Voici une femme du South Side qui possède une voix d’or. Si elle chantait le blues, elle serait une autre Bessie Smith. Ce qu’elle chante est appelé gospel. Écoutez.»(2)Outre l’insistance de son producteur Art Freeman, le passage de ses premiers disques à la radio a également contribué à ce que la patronne des disques Apollo, Bess Berman, lui accorde une seconde chance en septembre 1947, la bonne, celle d’où sortira Move On Up A Little Higher (1). Pour l’enregistrement de cette pièce, Mahalia était accompagnée par son «pays» «Two-Finger-Picking» James Lee dont le surnom évoque une technique pianistique rudimentaire! Or c’est Robert Anderson qui était alors son pianiste régulier (3). Pourtant la chanteuse téléphone à James Lee à la grande surprise de celui-ci : «Je ne m’étais jamais considéré comme un pianiste, je chantais, nous chantions en duo.»(2)

Mais James Lee ne renouvellera pas l’expérience et, pour la séance suivante, proposera à Mahalia une de ses amies d’école, Mildred Carter.«Elle joue à présent à Big Mt. Moriah, du côté de Dearborn.Cette fille m’a déjà approché.Je pense qu’elle fera l’affaire, Mahalia. Veux-tu que j’aille la chercher de ta part?»(2)Mahalia se renseigne et, après quelques hésitations, engage Mildred... Elle restera sa pianiste pendant vingt ans (4). Quant à l’organiste qui l’accompagnera le plus régulièrement durant les années 47/50, c’est James Herbert dit «Blind» Francis, musicien aveugle né en 1914 que Mahalia avait rencontré en 1942. De cette première séance avec Mildred Carter-Falls est issu Dig A Little Deeper, autre gros succès commercial dont nous vous proposons ici une prise différente de celle figurant dans notre premier volume (5). Un guitariste s’ajoute au duo piano/orgue : Samuel Patterson, également bon chanteur de spirituals qui enregistrera sous son nom pour Apollo en 1949 mais sans succès.Studs Terkel, après une nouvelle interview radiophonique, programme Mahalia Jackson dans son nouveau show TV «Studs Place», une première pour la musique gospel. Le président de la Convention baptiste, le Dr. D.V. Jemison, lui demande d’être leur soliste officielle lors de la prochaine convention nationale. Ainsi en peu de temps, le train de vie de Mahalia change même si son auditoire reste majoritairement noir. Dure en affaires, elle demande à être payée cash à chaque prestation : de 1000 à 1500 dollars par soirée dans les grandes salles et les clubs de New York et de Chicago, un peu moins dans les églises. Sa vie privée suit le mouvement. Divorcée de Ike Hockenhull, Mahalia multiplie les aventures car «une femme sans un homme est comme un ballon égaré dans les broussailles» dit-elle à Laurraine Goreau (2).

Et, s’adressant au public lors d’un concert, elle lance : «Parmi tous les beaux messieurs que je vois ici cette nuit, je dois bien être capable de trouver un mari!»(6) De fait, parmi ses nombreuses relations, elle rencontre à cette époque Sigmund «Minters» Galloway, avec qui elle finira par se marier... mais pas avant 1965!Pour qui ne se fie qu’à ses prestations des années 60 lorsqu’elle avait tendance à privilégier la partie la plus emphatique ou grandiloquente de son répertoire – celle qui plaisait le plus à un public européen peu averti – ou aux nombreuses photographies qui la représentent avec un air de sainteté, cet aspect de sa personnalité peut surprendre. Pourtant nombreux sont les commentaires qui témoignent d’une présence scénique extrêmement charnelle, voire sexuelle, ce qui ne fait que confirmer la dimension physique et corporelle que l’on reconnaît d’habitude comme s’ajoutant à l’expression vocale de la communauté afro-américaine lors des manifestations religieuses. Ainsi on parle du belly-dancing (la danse du ventre) de Mahalia Jackson sur scène. Comme Maurice Cullaz le rapportait lors du décès de la grande chanteuse : «Les musiciens et le public de couleur ont rendu hommage au swing (au sens large du mot), à la sensualité et à la féminité de Mahalia.»(7) Et, citant l’un de ses biographes de couleur, Maurice traduit : «Spirituellement parlant, Mahalia ramenait parfois ses auditeurs de couleur au temps de l’esclavage. Elle assumait, sans aucune fausse pudeur, son héritage culturel du Sud profond, se lamentant bruyamment et hurlant à pleine voix sa peine, comme on le fait dans les églises du Sud, se dandinant, dansant en extase comme le font les preachers de la Sanctified Church.

Certaines églises ne voulaient plus l’employer car leurs fidèles étaient scandalisés par ses déhanchements (snake hips) mais la plupart des croyants raffolaient de ses cris de jubilation et des pas de danse qu’elle improvisait, tout en découvrant un peu ses chevilles et même ses mollets (...) Mahalia fut toujours ce qu’il y avait de plus sexy (the sexiest thing) dans toutes nos manifestations de ferveur religieuse.»(7) Voilà qui tranche avec l’image de «mémé» puritaine que certains lui attribuent de ce côté-ci de l’Atlantique.Mahalia chante au Golden Gate Ballroom, l’un des «temples» de Harlem où se produisent les plus grands orchestres noirs : Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Lucky Millinder (avec Rosetta Tharpe), Cootie Williams, Buddy Johnson... et engage Joe Bostic, un ancien journaliste sportif noir devenu DJ/manager, comme agent. Elle rencontre également le grand découvreur de talents, John Hammond. Celui qui fit entrer la musique noire authentique au Carnegie Hall avait écrit un article sur elle dans un journal new-yorkais. Son impresario, Johnny Meyers, imagine alors une rencontre entre Mahalia Jackson et son amie et rivale Ernestine Washington alors très populaire à New York où elle enregistre depuis 1943. Meyers organise donc une «East and West Battle» le 11 avril 1948 dans un Golden Gate plein à craquer. En fait de bataille, cela s’avère surtout une excellente opération publicitaire et Mahalia «casse la barraque» avec Move On Up. «Le gospel possédait une superstar».(2)Un concert est alors envisagé à l’Apollo Theatre (8) «mais Miss Jackson ne veut pas mélanger le gospel à cette sorte de pop music (sic) que vous mettez ici»(2) et elle rentre à Chicago.Coup de fil de la maison Decca qui lui demande d’accepter que Sister Rosetta Tharpe elle-même enregistre sa propre version de Move On Up. Après discussions et moyennant compensations financières, Mahalia donnera son accord (9).

Elle envisage avec Theo Frye, l’un des anciens proches de Dorsey, la création d’une Music Convention à l’intérieur de la Baptist Convention. Puis la chanteuse part en tournée avec Mildred Falls et Blind Francis. On relève par exemple que le 6 juin, dans un stade de base ball d’Atlanta, elle chante devant 21000 personnes, la plus grande foule noire jamais rassemblée pour un concert. Demeurant quelques jours dans la capitale de la Géorgie, elle participe à plusieurs offices religieux et rencontre «le Pasteur Martin Luther King, un excellent preacher, très cultivé, un homme important à la Convention et à la NAACP.»(10)À New York en juillet, le propriétaire du Village Vanguard, Max Gordon, veut l’engager pour une semaine et lui propose 5000 dollars. Bien que pressée d’accepter par beaucoup de personnes, Mahalia décline l’invitation tout en remerciant Gordon car elle refuse toujours de se produire dans un night club.La Music Convention est inaugurée officiellement à Houston en septembre 1948 avec Theo Frye comme président et Mahalia Jackson comme... trésorière ! Mahalia donne également deux concerts en sa ville natale de la Nouvelle Orléans. À cette occasion le père, Johnny Jackson, rencontre pour la première fois Mildred Falls qui, en fille du Nord n’ayant jamais mis les pieds dans le Sud, supporte très mal la ségrégation raciale. «Vous et ma fille formez une bonne équipe, lui dit le père Jackson, je suis fier que vous soyez avec elle. Chaque fois que je pourrai faire quelque chose pour vous, faîtes-le moi savoir.»(2)En mars 1949 dans les bureaux de Apollo, Mahalia reçoit la visite du critique français Hugues Panassié accompagné de sa collaboratrice Madeleine Gautier et de Milton «Mezz» Mezzrow.

«Mezz a eu l’idée de me passer un disque d’une certaine Mahalia Jackson et nous avons été immédiatement impressionnés par sa voix et son style de chant»(2) raconte Panassié qui passera Amazing Grace et In My Home Over There à la «Radiodiffusion Française» (écoutée également dans les pays voisins). Quelques mois plus tard il écrit un article sur la chanteuse dans La Revue du Jazz et voilà comment Mahalia, dont les disques vont bientôt être publiés en France et en Angleterre par Vogue, va acquérir sa première audience internationale. (Comme souvent, la reconnaissance d’un artiste ou d’un mouvement passe par l’Europe avant qu’il soit «accepté», voire récupéré, par l’Amérique blanche). Avec Mahalia Jackson comme figure de proue, la marque Apollo est devenue un label important sur la Côte Est avec à son catalogue des noms comme les Roberta Martin Singers, le Rev. B.C. Campbell, les Dixie Hummingbirds, les Reliable Jubilee Singers, les Southern Harmonaires (11), etc. Curieusement, Mahalia ne retourne en studio qu’en juillet 1949, soit près d’un an et demi après sa précédente séance. Le matériel étant déjà abondant et les disques se vendant toujours bien, les producteurs n’ont peut-être pas jugé urgent de mettre de nouveaux morceaux sur le marché. Elle enregistre à cette occasion six titres dont I Can Put My Trust In Jesus, un gospel blues qu’elle chantait autrefois en duo avec James Lee et qui obtiendra en 1952 en France le Grand Prix de l’Académie du Jazz ainsi que Let The Power Of The Holy Ghost Fall On Me (12).

Elle reprend également le Prayer Changes Things composé par Robert Anderson et qu’Ernestine Washington avait gravé au mois de décembre précédent. Ce sera son nouveau grand succès. Puis la chanteuse reprend la route... le Mississippi, New Orleans, Bâton Rouge, retour à New York avec Anderson, à Washington... Elle se trouve à Los Angeles pour la National Baptist Convention annuelle et donne une série de récitals dans les églises californiennes. C’est aussi à cette époque que, sans doute pour des histoires de sous, Mahalia met fin à ses relations amicales et professionnelles avec Johnny Meyers, son plus important impresario new yorkais. Mahalia Jackson célèbre le Mother’s Day 1950 (la fête des mères) en donnant un impressionnant concert au Golden Gate Ballroom, ce qui donne l’idée au programmateur de l’Apollo Theatre de réunir sur une même affiche Mahalia Jackson et Sister Rosetta Tharpe (13).Pour sa séance suivante, W.H. Brewster, l’auteur de Move On Up, lui offre un morceau d’une cuvée équivalente, Just Over The Hill dont les deux faces du 78 tours s’envolent à leur tour vers les plus hautes cîmes du succès. «Brewster a probablement été le premier à introduire les formes du blues et de la valse dans le gospel» écrit Anthony Heilbut (14). Né en 1897 dans le Tennessee, le futur Rev. W. Herbert Brewster s’est installé vers la fin des années 20 à Memphis où il s’est rapidement taillé une réputation de «W.C. Handy du gospel». Peu avant 1940, il découvre la chanteuse Queen C. Anderson pour qui il écrit Move On Up A Little Higher que Mahalia Jackson reprendra avec le succès que l’on sait (1). Suivront Just Over The Hill puis I’m Getting Nearer My Home, These Are They et How Got Over. Il est aussi, à la fin des années 40, l’auteur des plus grands succès des Clara Ward Singers.

«Les chansons de Brewster étaient d’une structure plus complexe que ceux de Thomas Dorsey. Il a été le premier à composer des airs qui démarraient «lent et mélancolique», avec des cadences mélismatiques qui rappelaient les hymnes du Dr. Watts, avant de s’installer dans le tempo. Les paroles étaient chargées d’images bibliques.»(14) Au cours de la même séance, Mahalia enregistre I Do, Don’t You, très bel hymne lent dans lequel «le phrasé est parfait, le contralto ferme, résolu et granuleux, angélique mais jamais «mielleux» (...) elle ne «force» pas.»(14)Joe Bostic, le DJ de New York, venait d’inaugurer chaque dimanche matin sur la station de radio WLIB un programme de gospel en direct qui obtenait beaucoup de succès. Devenu l’agent de Mahalia, il a l’idée d’organiser un concert pour elle au Carnegie Hall, à la grande surprise de la chanteuse qui ne s’estime pas digne de paraître sur une scène aussi prestigieuse. D’abord réticente, elle finit par se laisser persuader. Pendant ce temps, en Europe, les choses avancent. Vogue publie sous son n°301 In My Home Over There et Since The Fire Started Burning et Max Jones écrit un article sur Mahalia dans la revue anglaise Melody Maker. Mais avant de franchir l’Atlantique, Mahalia Jackson parcourt toujours les routes des États-Unis : Virginie, Louisiane, Texas (un concert au Yates Auditorium de Houston devant 5000 personnes)... Elle chante aussi dans sa ville de Chicago, au Harlem’s Rockland Place en juillet et, lors du meeting baptiste de Germantown (Pennsylvanie) auquel elle participe, elle s’associe au jour de prière organisé pour les soldats américains envoyés en Corée. En août, elle se produit dans les écoles et les églises de Détroit, et en septembre est présente pour la Convention baptiste nationale qui a lieu à Philadelphie.

C’est le 11 septembre qu’elle enregistre deux nouveaux morceaux, selon Laurraine Goreau (15), tandis que la date du concert au Carnegie Hall est fixée au 1er octobre. Accompagne l’événement un article dans Ebony, le premier sur un artiste de gospel à paraître dans cette jeune revue noire.Au début de la semaine précédent le grand jour, Mahalia appelle en vain James Francis. L’organiste est introuvable et l’on apprend qu’il est parti en vacances pour un mois à la Nouvelle Orléans ! Bostic convoque alors en catastrophe une certaine Louise Overall Weaver qui accompagne habituellement le Rev. Thurston à la 44th Street Baptist Church de Chicago. Le concert a lieu à bureaux fermés. Impressionnée de se trouver dans une salle qui a entendu résonner les voix de Caruso, de Marian Anderson, de Paul Robeson, de Lawrence Tibbett et de Lily Pons, Mahalia Jackson interprète avec la plus grande ferveur A City Called Heaven, I’m A Poor Pilgrim Of Sorrow, I Walked Into The Garden, It Pays To Serve Jesus et Amazing Grace devant une assistance qui l’ovationne. La presse relate l’événement, le New York Times, le Herald Tribune, le New York Amsterdam News (qui titre «Mahalia Jackson, la diva de tous les chanteurs de gospel»), le New York Beat y consacrent leurs colonnes et John Hammond écrit dans le New York Daily Compass : «Mahalia possède une voix d’un pouvoir, d’une étendue et d’une souplesse énormes, et elle l’a utilisée avec un naturel hardi. Elle a une personnalité rayonnante, exprimant une passion religieuse et chaleureuse.»(2) Après cette grandiose prestation et toujours avec Louise Overall, Mahalia complète ses enregistrements, gravant notamment plusieurs œuvres chantées au Carnegie Hall ainsi que These Are They, une superbe pièce due à la plume de Brewster et de Virginia Davis (16). Puis elle participe en décembre 1950 à son premier show TV pour la chaîne nationale CBS avant de se reposer quelques temps chez elle à Chicago.Pendant ce temps l’avisé Joe Bostic, suite au Grand Prix du Disque que Mahalia Jackson venait de recevoir en France pour I’m Glad Salvation Is Free (17), commence à envisager une série de récitals à Paris...

Jean Buzelin

Auteur de Negro Spirituals et Gospel Songs, Chants d’espoir et de liberté (Ed. du Layeur/Notre Histoire, Paris 1998)

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS, GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2001

Notes :

(1) Voir Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol.1 (FA 1311).

(2) Cité dans Mahalia de Laurraine Goreau (cf. ouvrages consultés).

(3) Membre fondateur des Roberta Martin Singers, Robert Anderson a dit : «Mahalia a été la première à amener le blues dans le gospel.» Ce qui n’est pas tout à fait exact (voir Rosetta Tharpe) mais montre bien le lien évident entre Bessie Smith et Mahalia Jackson.

(4) Mildred Falls est décédée en 1972, la même année que Mahalia.

(5) La prise ici proposée est «brute», c’est-à-dire débarassée des claps (battements de mains) qui ont été rajoutés sur le LP Grand Award 33-390.

(6) Cité dans Got To Tell It de Jules Schwerin (cf. ouvrages consultés).

(7) Maurice Cullaz, Mahalia Jackson, in Jazz Hot n°281/avril 1972.

(8) Il n’y a aucune relation entre le fameux music-hall noir de Harlem et la maison de disques du même nom

(9) Sister Rosetta Tharpe enregistra Move On Up (en deux parties) en janvier 1949.

(10) C’est sa première rencontre avec le futur grand leader noir déjà engagé dans la NAACP (Association nationale pour l’avancement des gens de couleur). (cf. 2)

(11) Les Southern Harmonaires enregistreront pour Apollo en 1950 avant d’accompagner Mahalia Jackson dans son célèbre In The Upper Room.

(12) Contrairement à ce qu’indiquent les discographies, nous n’avons identifié qu’une seule prise de Let The Power. Par contre il existe deux prises différentes de Walk With Me gravé le même jour ; la première a été publiée sur le 78 tours Apollo 217, mais c’est la seconde, sans la guitare, qui a fait l’objet de nombreuses éditions et rééditions ultérieures, tant en LP qu’en CD.

(13) Ce projet ne semble pas s’être réalisé.

(14) Cité dans The Gospel Sound d’Anthony Heilbut (cf. ouvrages consultés).

(15) Sur ce sujet, les discographies sont floues car les dix numéros de matrice se suivent sans interruption. Jules Schwerin coupe la poire en deux : cinq titres sont attribués au 11 septembre, les cinq autres au 17 octobre.

(16) Virginia Davis figure parmi les plus prolifiques compositeurs de gospel des années 40 : elle est notamment co-auteur de Move On Up et de I’m Getting Nearer My Home avec Brewster et de I Have A friend avec Frye.

(17) Le Hot-Club de France a décerné son «Prix du chant religieux» à I’m Glad Salvation Is Free en 1951 et à Move On Up A Little Higher en 1952.

Ouvrages consultés :

Laurraine Goreau : Mahalia (Lion Publishing, UK 1976 - 2e édition)

Jules Schwerin : God to Tell It : Mahalia Jackson, Queen of Gospel (Oxford University Press, 1992)

Anthony Heilbut : The Gospel Sound (Limelight Ed., NY 1992 - 4e édition)

Robert Sacré : Les Negro Spirituals et les Gospel Songs (Que Sais-je?, PUF, Paris 1993)

Denis-Constant Martin : Le Gospel afro-américain (Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, Paris 1998).

Nous remercions particulièrement Daniel Gugolz, Jacques Morgantini et Alain Tomas pour leur prêt de 78 tours et autres documents sonores, ainsi que Andrew Griffith, François-Xavier Moulé, Friedrich Mühlöcker et Étienne Peltier pour leur collaboration.

Photos et collections : Pierre Allard, Frank Driggs, Jacques Morgantini, X (D.R.) et Gilles Pétard qui nous a aimablement prêté la photo de couverture.

Nous dédions ce volume à la mémoire de Maurice Cullaz.

english notes

By the beginning of 1948, Mahalia Jackson had suddenly made a reputation for herself, at least with black audiences who adopted her as one of their idols.After a lot of hard work, particularly on the road, from the early 40s she became well-known as a gospel singer — tours with Thomas A. Dorsey (1), a yearly appearance at the National Baptist Convention etc. — the singer’s life changed radically in the space of a year. Although they did not sell very well, the records she cut in the autumn of 1946 had attracted the attention of Chicago author/actor/reporter J. Louis “Studs” Terkel. Particularly moved by I’m Going To Tell God, her first record (Apollo 110), he interviewed her during the radio show “The Wax Museum” on Chicago’s WENR station. Studs Terkel was one of the first white disc jockeys to broadcast black performers on a white radio station, which encouraged the black population to listen to the show. Terkel introduced Mahalia like this: “There’s a woman on the South Side with a golden voice. If she were singing the blues she’d be another Bessie Smith. What she sings is called gospel. Listen.” (2)In addition to the support of her producer Art Freeman, the radio airing of her early records persuaded the head of the Apollo label, Bess Berman, to give her a second chance in September 1947, a session that produced Just A Little Higher (1). She was accompanied on this piece by “Two-Finger-Picking” James Lee whose nickname suggests a fairly rudimentary piano technique! Robert Anderson had previously been her regular accompanist (3). However, to his great surprise, Mahalia phoned James Lee: “I’d never considered myself a pianist. I sang: We sang duets together.” (2)But James Lee was not tempted to renew the experience and suggested that Mahalia use an old school friend of his, Mildred Carter: “She’s playing at Big Mt. Moriah right now.

That girl’s been coming around me already. I think she’ll do, Mahalia. You want me to send her to you?” (2)Mahalia made a few enquiries and, after hesitating a while, hired Mildred who would remain her pianist for twenty years (4). The organist who would accompany her most frequently during 1947/50 was James Herbert, known as “Blind” Francis, a blind musician born in 1914 and whom Mahalia had met in 1942. From this first Mildred Carter-Falls session came the huge hit Dig A Little Deeper. The version included here is not the same as that on our first volume (5). In addition to the piano/organ duet, we have guitarist Samuel Patterson, who was also an excellent gospel singer who recorded under his own name for Apollo in 1949 but without any great success.Studs Terkel, after a further radio interview, invited Mahalia Jackson on to his new TV show “Stud’s Place”, a first for gospel music. As a result, Mahalia’s life-style suddenly changed, although the majority of her fans were still black. She was a hard business woman and demanded cash payment for every appearance: from $1000 to $1500 a night in big New York and Chicago night clubs, a little less for church appearances.Her private life followed the same rhythm. After having divorced Ike Hockenhull, she embarked on several affairs for “a woman without a man is like a lost ball in high weeds” as she confided to Laurraine Goreau (2). And, talking directly to her audience during a concert, she declared “Out of all the good-looking men I see here tonight, I ought to be able to get myself a husband!” (6) In fact, it was around this time that she met Sigmund “Minters” Galloway whom she finally married, but not until 1965! This aspect of Mahalia may surprise some fans who are only familiar with what she was singing in the 60s – intended for an uninformed European public – accompanied by press shots depicting her in a saintly attitude.

However, her on-stage presence has often been described as sensual, even sexual, but this was only an example of the bodily expression that often accompanied Afro-American vocal expression during a religious service. Some people have mentioned Mahalia Jackson’s belly-dancing on stage but as Maurice Cullaz wrote on her death: “Musicians and black audiences have rendered homage to the swing (in the wide sense of the term), the sensuality and femininity of Mahalia.”(7). Quoting from one her biographies, Maurice added “Spiritually Mahalia often brought her black listeners back to the times of slavery. She did not hesitate to assume her “deep South” heritage, crying out her pain as they did in the southern churches, letting herself go in an exctasy of dancing just like the preachers of the Sanctified Church. Some churches no longer wanted to hire her because her snake hip movements shocked some of the faithful but most of the congregation loved her jubilant cries and her improvised dance steps (that did reveal her pretty ankles and legs…). “Mahalia was always the sexiest thing in religion.” (7) Not at all like the “Puritan granny” image that some Europeans attributed to her.Mahalia sang at the Golden Gate Ballroom, one of the temples of Harlem where most of the great black orchestras appeared: Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Lucky Millinder (with Rosetta Tharpe), Cootie Williams, Buddy Johnson… and hired Joe Bostic, a black ex-sports reporter turned DJ/Manager, as her agent. She also met the great talent scout John Hammond, responsible for introducing authentic black music to Carnegie Hall. He wrote an article about her in a New York daily. Then, on 11 April 1948, in a packed Golden gate, her impresario, Johnny Meyers, organised the “East and West Battle” between Mahalia Jackson and her friend and rival Ernestine Washington, who was very popular in New York where she had been recording since 1943. In fact, the contest turned out to be an excellent publicity stunt for Mahalia brought the house down with Move On Up. “Gospel had a superstar.”(2)

A further concert was envisaged at the Apollo Theater (8) “but Miss Jackson doesn’t mix gospel with that kind of pop music they put up here”(2) and she returned to Chicago.Decca phoned her to ask if she would allow Sister Rosetta Tharpe to record Mahalia’s version of Move On Up. After various discussions and a financial agreement Mahalia accepted (9). With Theo Frye, al old associate of Dorsey, she began to consider setting up a Music Convention within the Baptist Convention. Then she went on tour with Mildred Falls and Blind Francis.On 6 June, in a baseball stadium in Atlanta, she sang in front of 21,000 people, the biggest black audience ever at a concert. She stayed several days in the capital of Georgia, attending several religious services and meeting “Pastor Martin Luther King Sr., such a fine preacher, so educated – a big man in the Convention and in the NAACP too.”(10)In July Max Gordon, the proprietor of the Village Vanguard in New York, wanted to hire her for a week and offered her 5000 dollars. Although a lot of people pushed her to accept, Mahalia declined the invitation for she always refused to appear in a night club. The Music Convention was officially inaugurated in Houston in September 1948 with Theo Frye as president and Mahalia Jackson as treasurer! Mahalia also gave two concerts in her native New Orleans town. It was on this occasion that her father, Johnny Jackson, first met Mildred Falls who had never set foot in the South before, finding racial segregation insupportable. “You and my daughter make a good team; I’m proud you’re with her. Anything I can do, just let me know.”(2)In March 1949, in the Apollo offices, Mahalia received the visit of French critic Hugues Panassié, accompanied by Madeleine Gautier and Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow.

“Mezz had the idea of trying a record by one Mahalia Jackson and we were immediately impressed by her voice and her style of singing”(2) recounts Panassié who broadcast Amazing Grace and In My Home Over There on “Radiodiffusion Française” (also heard in neighbouring countries). A few months later he wrote an article on the singer in La Revue du Jazz which is how Mahalia, whose records would soon be issued in France and England by Vogue, reached her first international audience. (As is often the case, an artist or a movement is frequently recognised in Europe before being accepted, and even taken over, by white Americans).With Mahalia Jackson as a figurehead, Apollo soon became one of the most important labels on the East Coast, its catalogue including Roberta Martin Singers, the Reverend B.C. Campbell, the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Reliable Jubilee Singers, the Southern Harmonaires (11) etc. Curiously enough, Mahalia did not return to the studios until July 1949, almost a year and a half after her previous session. Perhaps her numerous records were selling so well that the producers did not consider it necessary to put any more on the market. On this occasion she cut six titles, among them I Can Put My Trust In Jesus, a gospel blues that she had previously sung as a duet with James Lee and that in 1952 was awarded the Grand Prix de l’Académie de Jazz in France, and Let The Power Of The Holy Ghost Fall On Me (12). She also reprised Prayer Changes Things composed by Robert Anderson which Ernestine Washington had recorded the previous December. This turned out to be another great hit. Then Mahalia went back on the road again… Mississippi, New Orleans, Baton Rouge, back to New York with Anderson, Washington… then Los Angeles for the annual National Baptist Convention where she gave a series of concerts in Californian churches. It was also at this time that Mahalia, probably as a result of disagreements about money, ended her professional and friendly relationship with Johnny Meyers, her most important New York impresario.Mahalia celebrated Mothers’ Day 1950 with an impressive concert at the Golden Gate Ballroom which gave the Apollo Theater the idea of putting Mahalia Jackson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe on the same bill (13).

For her following session, W.H. Brewster, composer of Move On Up, came up with a similar title Just Over The Hill on two sides of a 78 which also became a tremendous hit. According to Anthony Heilbut, “Brewster was probably the first to combine the blues and waltz forms in gospel.” (14) Born in Tennessee in 1897, the future Rev. W. Herbert Brewster settled in Memphis in the late 20s where he soon made a name for himself as the “W.C. Handy of Gospel”. Just before 1940 he discovered the singer Queen C. Anderson for whom he wrote Move On Up A Little Higher that Mahalia Jackson reprised with the above-mentioned success (1). Then came Just Over The Hill, followed by I’m Getting Nearer My Home, These Are They and How Got Over. Towards the end of the 40s he also wrote some of the Clara Ward Singers’ biggest hits. “Brewster’s songs were structurally more complex than those of Dorsey. He was the first to compose tunes that commenced “slow and mournful” with melismatic cadenzas reminiscent of dr. Watts hymns, and then picked up the tempo. The lyrics were filled with biblical images…” (14) During the same session Mahalia recorded the beautiful slow hymn I Do, Don’t You in which “the phrasing is perfect, the contralto sturdy and grainy, angelic but never saccharine (…) she doesn’t growl.” (14)Joe Bostic, the New York DJ, had just started a Sunday morning programme on WLIB radio of live gospel which became very popular. As Mahalia’s agent, he had the idea of organising a concert for her at Carnegie Hall, to the singer’s great surprise for she did not consider herself good enough to appear on such a prestigious stage. However, she finally let herself be persuaded. Meanwhile, things were also taking off in Europe. Vogue (n° 301) issued In My Home Over There and Since The Fire Started Burning and Max Jones wrote an article on Mahalia in the English “Melody Maker”.

But, before crossing the Atlantic, Mahalia Jackson continued to tour the United States: Virginia, Louisiana, Texas (a concert in Houston’s Yates Auditorium in front of a 5000 strong audience…). She also sang in her hometown Chicago in July, at Harlem’s Rockland Place and, while taking part in a Baptist meeting in Germantown, Pennsylvania, she joined in prayers for US soldiers serving in Korea. In August she appeared in churches and schools around Detroit and, in September, was present at the National Baptist Convention that took place in Philadelphia. According to Laurraine Goreau (15) it was on 11 September that she recorded two new titles, while the date for the Carnegie hall concert was 1 October. The event was accompanied by an article in “Ebony”, the first on a gospel singer to appear in this new black magazine. At the beginning of the week preceding the great day Mahalia tried in vain to contact organist James Francis, only to discover that he had left for a month’s vacation in New Orleans! A desperate Bostic called on a certain Louise Overall Weaver who regularly accompanied the Reverend Thurston at the 44th Street Baptist Church in Chicago. The concert was a sell-out. Overwhelmed at finding herself in a hall that had echoed to the likes of Caruso, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Lawrence Tibbett and Lily Pons, Mahalia gave her all on A City Called Heaven, I’m A Poor Pilgrim Of Sorrow, I Walked Into The Garden, It Pays To Serve Jesus and Amazing Grace before an audience that went wild in their acclaim. The “New York Times”, the “Herald Tribune”, the “New York Amsterdam News” (with the headline “Mahalia Jackson, the diva of gospel singers”), the “New York Beat” all reported the event. John Hammond wrote in the “New York Daily Compass” “Mahalia has a voice of enormous power, range and flexibility, and she used these with reckless abandon. She has a glowing personality, exuding warmth and religious passion.” (2)After this grandiose performance and still accompanied by Louise Overall, Mahalia completed her recordings, notably several titles she had sung at Carnegie Hall, including the superb These Are They, written by Brewster and Virginia Davis (16). Then, in December 1950, she appeared on her first TV show for the national CBS channel, before going home to Chicago to take a little time off.It was at this point that the astute Joe Bostic, following the Grand Prix du Disque that Mahalia had just been awarded in France for I’m Glad Salvation Is Free (16), began to think seriously about a series of concerts in Paris…

Adapted from the French by Joyce Waterhouse

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS, GROUPE FRÉMEAUX COLOMBINI SA, 2001

Notes:

(1) See Complete Mahalia Jackson Vol. 1 (FA 1311)

(2) Quoted in Mahalia by Laurraine Goreau (cf. works consulted).

(3) Founder member of the Roberta Martin Singers, Robert Anderson said: “Mahalia was the first to bring the blues into gospel.” Which was not exactly true (see Rosetta Tharpe) but reveals the obvious link between Bessie Smith and Mahalia Jackson.

(4) Mildred Falls died in 1972, the same year as Mahalia.

(5) The “take” used here is without the clapping added on the Grand Award LP 33-390.

(6) Quoted in Got To Tell It by Jules Schwerin (cf. works consulted).

(7) Maurice Cullaz, Mahalia Jackson, in Jazz Hot n° 281/April 1972.

(8) There is no connection between the famous Harlem black music hall and the label of the same name.

(9) Sister Rosetta Tharpe recorded Move On Up (in two parts) in January 1949.

(10) This was her first meeting with the future black leader, already a member of the NAACP.

(11) In 1950 the Southern Harmonaires recorded for Apollo before accompanying Mahalia Jackson on her famous In The Upper Room.

(12) Contrary to what the discographies suggest, we have identified just one take of Let The Power. On the other hand, there are two different takes of Walk With Me cut on the same day; the first was issued on a 78 (Apollo 217) but it was the second, without guitar, that was later frequently reissued, either on LP or CD.

(13) This project does not appear to have been realised.

(14) Quoted in The Gospel Sound by Anthony Heilbut (cf. works consulted).

(15) Discographers remain somewhat vague on this subject as the ten matrix numbers follow each other without interruption. Jules Schwerin opts for the 50-50 solution: five titles are dated 11 September and the other five 17 October.

(16) Virginia Davis was one of the most prolific gospel composers in the 40s: she was co-writer of Move On Up and I’m Getting Nearer My Home with Brewster and of I Have A Friend with Frye.

(17) The Hot-Club de France awarded its “Prize for Religious Singing” to I’m Glad Salvation Is Free in 1951 and to Move On Up A Little Higher in 1952.

Works consulted:

Laurraine Goreau: Mahalia (Lion Publishing, UK 1976 - 2nd edition).

Jules Schwerin: God To Tell It: Mahalia Jackson, Queen of Gospel (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Anthony Heilbut: The Gospel Sound (Limelight Ed., NY 1992 - 4th edition).

Robert Sacré: Les Negro Spirituals et les Gospel Songs (Que Sais-je?, PUF, Paris 1993).

Denis-Constant Martin: Le Gospel Afro-Américain (Cité de la Musique/Actes Sud, Paris 1998).

With grateful thanks to Daniel Gugolz, Jacques Morgantini and Alain Tomas for their loan of 78s and other recordings, as well as to Andrew Griffith, François-Xavier Moulé, Friedrich Mühlöcker and Etienne Peltier for their collaboration.

Photos and collections: Pierre Allard, Frank Driggs, Jacques Morgantini, X (D.R.) and Gilles Pétard who lent us the cover photo.

This volume is dedicated to the memory of Maurice Cullaz.

DISCOgraphie

01. DIG A LITTLE DEEPER (K. Morris) C2194-alternake take

02. THERE’S NOT A FRIEND LIKE JESUS (Hugg - Oatman - arr. B. Smith) C2198-alternate take

03. I CAN PUT MY TRUST IN JESUS (K. Morris) C2285

04. LET THE POWER OF THE HOLY GHOST FALL ON ME (M. Jackson - B. Reles) C2286

05. (A) CHILD OF THE KING (Smith - Daniels) C2287

06. GET AWAY JORDAN (W. McDade - arr. B. Smith) C2288

07. WALK WITH ME (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson) C2289-master

08. WALK WITH ME (Trad. - arr. M. Jackson) C2289-alternate take

09. PRAYER CHANGES THING (R. Anderson) C2290

10. SHALL I MEET YOU OVER YONDER ? (Trad.) C2328

11. THE LAST MILE OF THE WAY (C.A. Tindley - arr. B. Smith) C2329

12. JUST OVER THE HILL Pt.1 & 2 (W.H. Brewster) C2330/C2331

13. I DO, DON’T YOU (Trad.) C2332

14. GOD ANSWERS PRAYERS (Trad.) C2333

15. I’M GLAD SALVATION IS FREE (Bowles - Hoyle) C2334

16. DO YOU KNOW HIM (Parker - arr. H. Boggs) C2335

17. I’M GETTING NEARER MY HOME (W.H. Brewster - V. Davis) C2400-5

18. I GAVE UP EVERYTHING TO FOLLOW HIM (Henderson) C2401

19. IT PAYS TO SERVE JESUS (Trad. - arr. T. House) C2402

20. THESE ARE THEY (W.H. Brewster - V. Davis - arr. M. Jackson) C2403

21. HE’S THE ONE (Matthews) C2404

Mahalia Jackson (vocal) with :

(1-2) Mildred Falls (piano), Herbert J. Francis (organ), Samuel Patterson (guitar). Chicago, 10 or 20/12/1947.

(3-9) Mildred Falls (piano, out on 5), Herbert J. Francis (organ), unknown (guitar, out on 5, 8). 15 or 21/07/1949.

(10-16) Mildred Falls (piano, out on 11, 13), Herbert J. Francis (organ), unknown (guitar on 12, 15, 16). New York City, 12/01/1950.

(17-18) Mildred Falls (piano), prob. Herbert J. Francis (organ). New York City, 11/09/1950.

(19-21) Mildred Falls (piano, out on 19), Louise Overall (organ). New York City, prob. 17/10/1950 (or 11/09/1950).

CD TITRE, ARTISTE © Frémeaux & Associés (frémeaux, frémaux, frémau, frémaud, frémault, frémo, frémont, fermeaux, fremeaux, fremaux, fremau, fremaud, fremault, fremo, fremont, CD audio, 78 tours, disques anciens, CD à acheter, écouter des vieux enregistrements, albums, rééditions, anthologies ou intégrales sont disponibles sous forme de CD et par téléchargement.)