- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

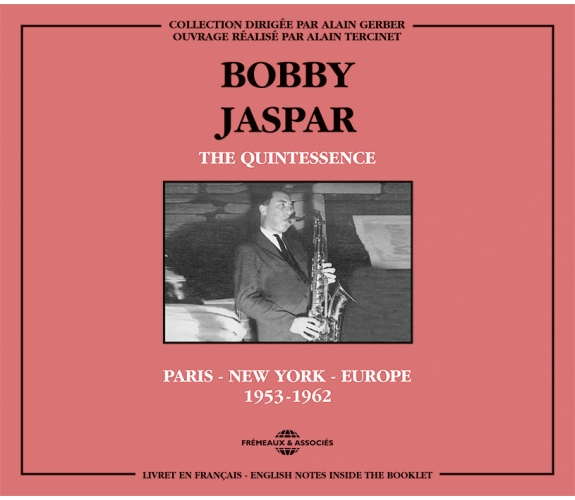

PARIS - NEW YORK - EUROPE - 1953-1962

BOBBY JASPAR

Ref.: FA3069

EAN : 3561302306926

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 42 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

PARIS - NEW YORK - EUROPE - 1953-1962

PARIS - NEW YORK - EUROPE - 1953-1962

“Like Django Reinhardt, bobby was one of the first jazz musicians who came from a totally European background and created his own jazz langage” David AMRAM

Frémeaux & Associés’ « Quintessence » products have undergone an analogical and digital restoration process which is recognized throughout the world. Each 2 CD set edition includes liner notes in English as well as a guarantee. This 2 CD set presents a selection of the best recordings by Bobby Jaspar between 1953 and 1962.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Jeepers CreepersBobby JasparJ. Mercer00:03:301953

-

2Struttin' With Some BarbecueBobby JasparL. Hardin00:03:351953

-

3BlossomBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:03:461954

-

4ParadoxBobby JasparAndré Hodeir00:02:301954

-

5There's A Small HotelBobby JasparL. Hart00:03:321954

-

6Très chouetteBobby JasparJimmy Raney00:04:301954

-

7More Than You KnowBobby JasparB. Rose00:02:431954

-

8Jeu de quartesBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:02:341954

-

9Paraphrase sur Saint-TropezBobby JasparAndré Hodeir00:04:211954

-

10Nory's QuickBobby JasparF. Coppieters00:02:271955

-

11The Nearness Of YouBobby JasparN. Washington00:03:501955

-

12MinorBobby JasparC. Chevallier00:02:311955

-

13AuraBobby JasparC. Chevallier00:03:391955

-

14A Long Way From HomeBobby JasparDave Amram00:04:471955

-

15The Way You Look TonightBobby JasparD. Fields00:04:191955

-

16B.S.O.P.Bobby JasparC. Chevallier00:02:511955

-

17How About YouBobby JasparR. Freed00:04:291955

-

18I Can't Get StartedBobby JasparV. Duke00:06:041955

-

19Memory Of DickBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:05:361955

-

20There Will Never Be Another YouBobby JasparM. Gordon00:02:091956

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1ClarinescapadeBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:03:081956

-

2Minor DropBobby JasparF. Coppieters00:04:261956

-

3In A Little Provincial TownBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:03:371956

-

4Cette choseBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:03:161957

-

5On A BluesBobby JasparAndré Hodeir00:05:051957

-

6Somewhere ElseBobby JasparJoe Puma00:05:571957

-

7Light BlueBobby JasparMal Waldron00:07:511957

-

8Old Devil MoonBobby JasparE.Y.Harburg00:06:431957

-

9Bag's New GrooveBobby JasparMilt Jackson00:05:591957

-

10Before DawnBobby JasparG. Wallington00:06:121957

-

11Sweet BlancheBobby JasparG. Wallington00:05:381957

-

12Scotch HopBobby JasparBill Byers00:02:481957

-

13Everything Happens To MeBobby JasparT. Adair00:04:191957

-

14Sacha Bill Et BobbyBobby JasparBill Byers00:03:571957

-

15Nature BoyBobby JasparAhbez Eden00:04:301957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Bull MarketBobby JasparAhbez Eden00:02:481958

-

2All Of YouBobby JasparCole Porter00:03:311958

-

3SukiyakiBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:06:321958

-

4More Of The SameBobby JasparT. Jones00:06:591958

-

5Fast FatsBobby JasparJ. Gilson00:06:071958

-

6Monsieur DeBobby JasparRené Urtreger00:05:001958

-

7Chez moiBobby JasparP. Misraki00:03:081959

-

8Kelly BlueBobby JasparW. Kelly00:10:491959

-

9TelefunkyBobby JasparTal Farlow00:06:331959

-

10Potlikken BluesBobby JasparBobby Jaspar00:06:211960

-

11Theme For FreddieBobby JasparRené Thomas00:04:141962

-

12Well You Needn'tBobby JasparThelonious Monk00:06:211962

-

13It Could Happens To YouBobby JasparJ. Burke00:07:241962

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

FA3069 Jaspar

COLLECTION DIRIGÉE PAR ALAIN GERBER

OUVRAGE RÉALISÉ PAR ALAIN TERCINET

BOBBY

JASPAR

THE QUINTESSENCE

PARIS - NEW YORK - EUROPE

1953-1962

LIVRET EN FRANÇAIS - ENGLISH NOTES

BOBBY JASPAR – DISCOGRAPHIE

CD 1 – Paris (1953/56)

BOBBY JASPAR / HENRI RENAUD QUINTET (New Sound from Belgium - Vogue LD143)

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, 22/05/1953

1. JEEPERS CREEPERS (J. Mercer, H. Warren) 3’30

2. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE (L. Hardin, L. Armstrong) 3’35

BOBBY JASPAR (New Jazz vol. 1 - Swing M33333)

Roger Guérin (tp, alto tuba) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Bib Monville (ts) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, 12/01/1954

3. BLOSSOM (B. Jaspar) 3’46

Nat Peck (tb) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) ; André Hodeir (arr) – Paris, 12/01/1954

4. PARADOX (A. Hodeir) 2’30

BERNARD PEIFFER AND HIS SAINT GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS ORCHESTRA (Blue Star BLP6842)

Roger Guérin (tp, alto tuba) ; Bib Monville, Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Bernard Peiffer (p) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; André Baptiste “Mac Kac” Reilles (dm) – Paris, 14/01/1954

5. THERE’S A SMALL HOTEL (L. Hart, R. Rodgers) 3’32

JIMMY RANEY (Jimmy Raney visits Paris - Vogue LD194)

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Jimmy Raney (g) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, 10/02/1954

6. TRÉS CHOUETTE (J. Raney) 4’30

BOBBY JASPAR (New Jazz vol. 2 - Swing M33338)

Buzz Gardner, Roger Guérin (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (as, b-cl) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Armand Migiani(bs) ; Fats Sadi (vib on 8) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Gérard Pochonet (dm) – Paris, 12/10/1954

7. MORE THAN YOU KNOW (B. Rose, E. Eliscu, V. Youmans) 2’43

8. JEUX DE QUARTES (B. Jaspar) 2’34

ANDRÉ HODEIR (Essais – Swing M33353)

Le Jazz Groupe de Paris : Jean Liesse, Buzz Gardner (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Jean Aldegon (as) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Armand Migiani (bs) ; Fats Sadi (vib) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jacques David (dm) ; André Hodeir (comp, arr, cond) – Paris, 13/12/1954

9. PARAPHRASE SUR SAINT TROPEZ (A. Hodeir) 4’21

BOBBY JASPAR QUARTET (Gone with the Winds… - Swing M33351)

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Guy Pedersen (b) ; André Baptiste “Mac Kac” Reilles (dm) – Paris, 20/04/1955

10. NORY’S QUICK (F. Coppieters) 2’27

BOBBY JASPAR ALL STARS (Gone with the Winds… - Swing M33351)

David Amram (frh) ; Raymond Lefebvre (fl) ; Claude Foray (oboe) ; Emile Debru (bassoon) ; Jean-Louis Chautemps (cl) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts, arr) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jacques David (dm) – Paris, 6/06/1955

11. THE NEARNESS OF YOU (N. Washington, H. Carmichael) 3’50

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ET SON QUINTETTE DE LA ROSE ROUGE (Pathé 45EA37)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Christian Chevallier (p, arr) ; Fats Sadi (vib) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) – Paris, 1/05/1955

12. MINOR (C. Chevallier) 2’31

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER & SON GRAND ORCHESTRE (Big & Small - Columbia FP1056)

Fred Gérard, Christian Bellest, Roger Guérin, Lucien Juanico (tp) ; Nat Peck, Charles Verstraete, André Paquinet (tb) ; David Amram (frh) ; Jean Aldegon (as) ; Bobby Jaspar, Jean-Louis Chautemps, Armand Migiani (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Christian Chevallier (p, arr, cond) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) – Paris, 2/05/1955

13. AURA (C. Chevallier) 3’39

DON RENDELL / BOBBY JASPAR (Rencontre à Paris - Swing M33344)

David Amram (frh, arr) ; Bobby Jaspar, Don Rendell (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Guy Pedersen (b) ; André Baptiste “Mac Kac” Reilles (dm) – Paris, 17/03/1955

14. A LONG WAY FROM HOME (D. Amram) 4’47

DAVID AMRAM / BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET (Swing LDM33355)

David Amram (frh, arr) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Eddie de Haas (b) ; Jacques David (dm) – Paris, 5/07/1955

15. THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT (D. Fields, J. Kern) 4’19

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ET SON ORCHESTRE (Formidable ! - Columbia FP1067)

Fred Gérard, Christian Bellest, Roger Guérin, Robert Fassin, Fernand Verstraete (tp) ; Benny Vasseur, Michel Paquinet, André Paquinet, Gaby Vilain (tb) ; Christian Kellens (b-tb) ; Jean Aldegon, Armand Migiani (as) ; Bob Spar aka Bobby Jaspar, Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Christian Chevallier (p, arr, cond) ; Fats Sadi (vib) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) – Paris, 13/11/1955

16. B.S.O.P. (C. Chevallier) 2’51

CHET BAKER & HIS QUINTET WITH BOBBY JASPAR (Barclay BLP84 042)

Chet Baker (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Maurice Vander (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, 26/12/1955

17. HOW ABOUT YOU ? (R. Freed, B. Lane) 4’29

THE BOBBY JASPAR ALL STARS (Modern Jazz au Club St Germain - Barclay 84 023)

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; René Urtreger (p) ; Sacha Distel (g on 18) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, 27-29/12/1955

18. I CAN’T GET STARTED (V. Duke, I. Gershwin) 6’04

19. MEMORY OF DICK (B. Jaspar) 5’36

BOBBY JASPAR AND BLOSSOM DEARIE (Barclay 74017)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Blossom Dearie (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Christian Garros (dm) – Paris, 16/01/1956

20. THERE WILL NEVER BE ANOTHER YOU (M. Gordon, H. Warren) 2’09

CD 2 – New York / Paris (1956/57)

BOBBY JASPAR (Quartet & Quintet - Columbia (Fr) FPX 123)

Bobby Jaspar (cl) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Nabil Totah (b) ; Elvin Jones (dm) – NYC, 12/11/1956

1. CLARINESCAPADE (B. Jaspar) 3’08

Bobby Jaspar (ts, fl, arr) ; Eddie Costa (p) ; Barry Galbraith (g) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) – NYC, 20/11/56

2. MINOR DROP (F. Coppieters) 4’26

3. IN A LITTLE PROVINCIAL TOWN (B. Jaspar) 3’37

JAY JAY JOHNSON QUINTET (Dial J. J. 5 - Columbia CL 1084)

Jay Jay Johnson (tb, trombonium) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Wilbur Little (b) ; Elvin Jones (dm) – NYC, 31/01/1957

4. CETTE CHOSE (B. Jaspar) 3’16

ANDRÉ HODEIR (Essais - Savoy MG 12104)

Donald Byrd, Idrees Sulieman (tp) ; Frank Rehak (tb) ; Hal McKusick (as, b-cl) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Jay Cameron (bs, b-cl) ; Eddie Costa (p, vib) ; George Duvivier (b) ; Bobby Donaldson (dm) ; André Hodeir (comp, arr, cond) – Hackensack, NJ, 5/03/1957

5. ON A BLUES (A. Hodeir) 5’05

HERBIE MANN / BOBBY JASPAR SEXTET (Flute soufflé - Prestige PRLP 7101)

Herbie Mann, Bobby Jaspar (ts, fl) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Joe Puma (g) ; Wendell Marshall (b) ; Bobby Donaldson (dm) – Hackensack, NJ, 21/03/1957

6. SOMEWHERE ELSE (J. Puma) 5’57

solos : Mann (ts), Flanagan, Jaspar (fl), Puma, Mann (fl), Flanagan, Jaspar (ts) Puma.

INTERPLAY FOR 2 TRUMPETS AND 2 TENORS (Prestige PRLP7112)

Webster Young, Idrees Sulieman (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar, John Coltrane (ts) ; Mal Waldron (p) ; Kenny Burrell (g) ; Paul Chambers (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) – Hackensack, NJ, 22/03/1957

7. LIGHT BLUE (M. Waldron) 7’51

solos : Jaspar, Sulieman, Coltrane, Young.

JAY JAY JOHNSON QUINTET (Dial J. J. 5 - Columbia CL 1084)

Jay Jay Johnson (tb, trombonium) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Wilbur Little (b) ; Elvin Jones (dm) – NYC, 14/05/1957

8. OLD DEVIL MOON (E. Y. Harburg, B. Lane) 6’43

MILT JACKSON (Bags & Flutes – Atlantic 1294)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Milt Jackson (vib) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Kenny Burrell (g) ; Percy Heath (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) – NYC, 21/05/1957

9. BAG’S NEW GROOVE (M. Jackson) 5’59

BOBBY JASPAR (Riverside RLP12-240)

Idrees Sulieman (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; George Wallington (p) ; Wilbur Little (b) ; Elvin Jones (dm) – NYC, 23/05/1957

10. BEFORE DAWN (G. Wallington) 6’12

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; George Wallington (p) ; Wilbur Little (b) ; Elvin Jones (dm) – NYC, 28/05/1957

11. SWEET BLANCHE (G. Wallington) 5’38

BOBBY JASPAR / SACHA DISTEL (Versailles 90M302)

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; René Urtreger (p) ; Sacha Distel (g) ; Paul Rovère (b) ; Al Levitt (dm) – Paris, 11/09/1957

12. SCOTCH HOP (B. Byers) 2’48

13. EVERYTHING HAPPENS TO ME (T. Adair, M. Dennis) 4’19

Add Billy Byers (tb)

14. SACHA, BILL ET BOBBY (B. Byers) 3’57

MILES DAVIS QUINTET (AFRS Radio Broadcast)

Miles Davis (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Tommy Flanagan (p) ; Paul Chambers (b) ; Philly Joe Jones (dm) - Birdland, NYC, 17-31/10/1957

15. NATURE BOY (E. Ahbez) 4’30

CD 3 – New York / Europe (1958/62)

BARRY GALBRAITH (Guitar and the Wind – Decca DL9200) Urbie Green, Chauncey Welsh, Frank Rehak (tb) ; Dick Hixson (b-tb) ; Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Eddie Costa (p, vib) ; Barry Galbraith (g) ; Milt Hinton (b) ; Osie Johnson (dm) ; Billy Byers (arr) - NYC, 16/01/1958

1. BULL MARKET (B. Byers) 2’48

HELEN MERRILL (The Nearness of You – EmArcy MG36134)

Helen Merrill (voc) ; Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Bill Evans (p) ; Barry Galbraith (g) ; Oscar Pettiford (b) ; Jo Jones (dm) ; George Russell (arr) – NYC, 21/02/1958

2. ALL OF YOU (C. Porter) 3’31

TOSHIKO AND HIS INTERNATIONAL JAZZ SEXTET (United Notions – MetroJazz E1001)

Doc Severinsen (tp) ; Rolf Kühn (cl, as) ; Bobby Jaspar (fl, bs) ; Toshiko Akiyoshi (p) ; René Thomas (g) ; John Drew (b) ; Bert Dahlander (dm) – NYC, 13/06/1958

3. SUKIYAKI (B. Jaspar) 6’32

DONALD BYRD / BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET (RTF Broadcast)

Donald Byrd (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Walter Davis Jr. (p) ; Doug Watkins (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) – Festival de Jazz, Cannes, 11/07/1958

4. MORE OF THE SAME (T. Jones) 6’59

JEF GILSON SEPTETTE (Spirit Jazz SJD 1)

Roger Guérin, Frenand Verstraete (tp) ; Luis Fuentes (tb) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Walter Davis Jr. (p) ; Doug Watkins (b) ; Art Taylor (dm) ; Jef Gilson (cond) – Cachan, France, 3/10/1958

5. FAST FATS (J. Gilson) 6’07

MICHEL HAUSSER (Vibes + Flute – Columbia FPX173)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Michel Hausser (vib) ; René Urtreger (p) ; Paul Rovère (b) ; Daniel Humair (dm) – Paris, 16/12/1958

6. MONSIEUR DE… (R. Urtreger) 5’00

BLOSSOM DEARIE (My Gentleman Friend – Verve MGV2125)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Blossom Dearie (voc, p) ; Kenny Burrell (g) ; Ray Brown (b) ; Ed Thigpen (dm) – NYC, 8-9/04/1959

7. CHEZ MOI (P. Misraki) 3’08

WYNTON KELLY (Kelly Blue – Riverside RLP12-298)

Nat Adderley (co) ; Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Benny Golson (ts) ; Wynton Kelly (p) ; Paul Chambers (b) ; Jimmy Cobb (dm) – NYC, 19/02/1959

8. KELLY BLUE (W. Kelly) 10’49

TAL FARLOW (The Guitar Artistry of Tal Farlow – Verve MGV8370)

Bobby Jaspar (fl, ts) ; Tal Farlow (g) ; Milt Hinton (b) – NYC, 15-16/12/1959

9. TELEFUNKY (T. Farlow) 6’33

THE JOHNNY RAE QUINTET (Opus de Jazz vol. 2 – Savoy MG12156)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; Johnny Rae (vib) ; Steve Kuhn (p) ; John Neves (b) ; Jake Hanna (dm) – Newark, NJ, 6/12/1960

10. POTLIKKER BLUES (B. Jaspar) 6’21

THOMAS/JASPAR QUINTET (RCA (It) PML10324)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; René Thomas (g) ; Amedeo Tommasi (p) ; Maurizio Majorana (b) ; Franco Mondini (dm) – Roma, prob. January 1962

11. THEME FOR FREDDIE (R. Thomas) 4’14

CHET BAKER (Chet Is Back – RCA (It) PML10307)

Chet Baker (tp) ; Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Amedeo Tommasi (p) ; René Thomas (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Daniel Humair (dm) – Roma, 5/01/1962

12. WELL YOU NEEDN’T (T. Monk) 6’21

THE BOBBY JASPAR QUARTET (At Ronnie Scott’s, 1962 - Mole Jazz 11)

Bobby Jaspar (fl) ; René Thomas (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Daniel Humair (dm) – London, late January 1962

13. IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU (J. Burke, J. Van Heusen) 7’24

NOTES DISCOGRAPHIQUES

HELEN MERRILL : Toutes les discographies donnent George Russell comme guitaristealors qu’il s’agissait de Barry Galbraith, Russell le confirma à Peter Pettinger, auteur de “Bill Evans – How My Heart Sings”.

THOMAS/JASPAR QUINTET : La date d’Octobre 1961 attribuée à cette séance romaine est sujette à caution, le quintette se produisant le 4 Janvier 1962 dans l’émission télévisée de la RAI “Tempo di Jazz”.

BOBBY JASPAR

1953 / 1962, UNE DÉCENNIE PRODIGIEUSE

« Le saxophoniste belge Bobby Jaspar qui avait quitté la France voici près d’un an pour s’établir en Océanie, vient de faire une visite au “Vieux Monde” : on aura pu l’entendre lors d’une des dernières émissions de Jazz Variétés. » (Jazz Hot, avril 1953)

Qui aurait pu se douter qu’un tel entrefilet préluderait à une embellie qui fera de Paris un centre incontournable du jazz moderne ? Et cela grâce à Bobby Jaspar, venu de Wallonie avec une conception particulièrement exigeante du dit jazz : « C’est lorsque j’entendis Boplicity que je quittai le laboratoire de chimie où je travaillais pour me consacrer entièrement à cette musique que je jugeais enfin digne d’un avenir esthétique exceptionnel (1). »

À l’occasion du Festival International du Jazz 1949, Jaspar s’était produit une première fois dans la capitale au sein des Bob Shots. Ils avaient partagé la scène avec les quintettes de Charlie Parker et de Miles Davis. Né à Liège le 20 février 1926, Bobby avait alors vingt-trois ans et pratiquait la clarinette depuis 1942. Avant de se tourner vers le ténor (2).

Visiteur assidu de la scène parisienne - son talent lui valut d’être salué dès 1951 par un article dans Jazz Hot (3) - , il ne s’imposa pas vraiment lors de sa première campagne de France. Faute d’engagements valorisants. Quelques remplacements auprès de Django Reinhardt au Club Saint-Germain, des prestations épisodiques au Bœuf sur le Toit en compagnie de Marcel Bianchi, un passage dans la formation de Jack Dieval… Quant à son enregistrement des deux ballades, Bobby’s Beep et You Are Too Beautiful, il n’avait guère soulevé l’enthousiasme de son chroniqueur. Bobby acceptera donc une proposition venue du dancing « Les cols bleus » de Papeete. Un engagement musicalement calamiteux qu’en ingénieur chimiste consciencieux il tentera de rentabiliser en explorant les vertus supposées de l’huile de foie de requin. Autre initiative désastreuse.

De retour à Paris, Jaspar constata un changement. Le « style que l’on joue relax au lieu de se cogner le nez sur tout ce que l’on rencontre » ainsi que le définissait Lester Young, avait maintenant pignon sur rue. Bobby qui l’avait adopté depuis belle lurette, pouvait compter tout autant sur le soutien des « modernistes » hexagonaux que sur l’appui de ses complices venus de Belgique : Francy Boland, René Thomas, Benoît Quersin, Christian Kellens, « Fats » Sadi.

Bobby Jaspar deviendra le porte-étendard, le catalyseur, le propagateur de ce style baptisé « cool » faute de mieux. À l’occasion de tournées diverses, nombre de musiciens viendront consacrer sa légitimité : Jimmy Raney, Buzz Gardner, Nat Peck tromboniste et arrangeur, le corniste David Amram, le saxophoniste baryton Jay Cameron, Don Rendell (alors le meilleur ténor cool anglais), Lee Konitz, Lars Gullin, Chet Baker (4).

Dave Amram : « Pratiquement chaque saxophoniste ténor était alors influencé par Prez. Mais, au point de vue mélodique, Bobby sut se dégager de cette allégeance. Ses points de référence étaient clairement européens, français ou belges À l’instar de Django Reinhardt, Bobby a été un des premiers musiciens de jazz qui, venu d’un arrière-plan complètement européen, créa un langage propre au bouquet bien spécifique (5). »

Lors de son premier séjour parisien, en compagnie de Henri Renaud, Bobby Jaspar avait disséqué les enregistrements du quintette de Stan Getz. Il en adoptera la formule, choisissant un guitariste comme interlocuteur. Dans l’album marquant son retour, « New Sound from Belgium », Jimmy Gourley tiendra ce rôle mais bientôt Sacha Distel le relaiera. Un partenaire idéal pour Bobby aussi bien musicalement qu’humainement.

Du fait de sa conversion au jazz délivré par le nonette de Miles Davis, Jaspar ne pouvait que se sentir concerné par le problème de l’écriture. Il se montrera un arrangeur d’une belle audace, opposant sur The Nearness of You une section de bois à un cor et à un ténor. Aucune expérience ne le rebutera : il fut l’interprète du Paradoxe signé André Hodeir, première œuvre dodécaphonique écrite pour un jazzman, « un premier pas marqué vers un élargissement des horizons du jazz » selon les notes de pochette. Une composition qui trouvera un écho au travers de son propre Jeux de Quartes.

Jaspar avait largement contribué à la création du Jazz Groupe de Paris dirigé par André Hodeir. « Je crois pouvoir affirmer que si une nouvelle évolution comparable à celle amorcée par la session Capitol a lieu en France, c’est à André Hodeir que nous le devrons (6). » Une admiration réciproque liait les deux musiciens : à propos de l’intervention de Bobby sur l’un de ses thèmes, André Hodeir écrira : « Certain solo de ténor de Paraphrase sur Saint-Tropez reste à mes yeux un joyau que le temps n’a pas déprécié (7). »

À l’écoute du premier 45 t de Christian Chevallier, les amateurs n’en crurent pas leurs oreilles. Sur Minor, Bobby Jaspar s’exprimait à la flûte. Jusque là, ses utilisateurs dans le jazz se comptaient sur les doigts d’une main - Alberto Socarras, Wayman Carver chez Benny Carter puis dans l’orchestre de Chick Webb, Harry Klee. Janvier 1950, à New York chez Lionel Hampton, Jerome Richarson enregistra un chorus de flûte sur There Will Never Be Another You ; Frank Wess fit de même en mars 1954 au cours d’une séance dirigée par Joe Newman et récidiva deux ans plus tard chez Basie, à l’occasion de The Midgets, véritable manifeste en faveur de la flûte. Sur la côte Ouest, dès 1950 Bud Shank l’utilisa chez Kenton, imité trois ans plus tard par Buddy Collette dans l’orchestre de Jerry Fielding. À Paris même, en septembre 1953, Gigi Gryce avait gravé deux morceaux à la flûte accompagné par Henri Renaud. Bobby Jaspar ne faisait que suivre un mouvement qu’il pressentait à juste titre riche en opportunités.

Son nom n’était plus tout à fait ignoré du grand public depuis que son quintette avait figuré à l’affiche de l’Olympia dans un programme mettant Juliette Greco en vedette. Rien d’étonnant dans ces conditions que l’on trouve cet entrefilet dans Music-Hall, revue spécialisée dans les variétés : « Le saxophoniste ténor belge Bobby Jaspar a épousé le 24 mars, à Liège, la pianiste et chanteuse Blossom Dearie. De nombreux musiciens français se sont rendus en Belgique à cette occasion pour assister à la cérémonie. »

Une union qui se délita rapidement. Elle permit toutefois à Bobby de concrétiser son rêve d’affronter la vraie vie du jazz. Sur place, à New York. Une initiative proprement insensée au milieu des années 1950.

Va débuter alors la seconde partie de cette décennie que, de son point de vue, l’on peut qualifier de prodigieuse. Un parcours à tout le moins contrasté, erratique, suscitant nombre d’interrogations sans réponses, les enregistrements ne représentant que la partie émergée de l’iceberg. Ainsi la collaboration de Bobby Jaspar avec le trio de Bill Evans ne laissa aucune trace, non plus que son travail au sein de la formation de douze musiciens réunie par Gil Evans.

Tout avait commencé sous les meilleurs auspices. Marié à une musicienne citoyenne des Etats-Unis, Bobby avait obtenu rapidement sa carte au Local 802, le syndicat des musiciens new yorkais. Comble de bonheur, à peine débarqué, le bassiste Mort Herbert l’avait invité à une séance d’enregistrement et, au mois de juin, le grand orchestre de Walter Gil Fuller l’avait accompagné (8). En septembre, dans son compte rendu du référendum des critiques organisé par Down Beat, Jazz Hot annoncera que, dans la catégorie New Stars, « chez les sax-ténors, Bobby Jaspar est premier, battant au sprint Charlie Rouse, Buddy Collette, Al Cohn, Frank Foster, Bill Holman et Guy Lafitte. »

« Tous ces musiciens m’aiment bien, viennent me le dire et ne manifestent pas le moindre soupçon de jalousie ou la peur de perdre leur place. » Jaspar est aux anges d’autant plus que J. J. Johnson l’a engagé dans son nouveau quintette, grâce, dit-on, à une recommandation de Miles Davis. L’entoureraient au piano Hank Jones que Tommy Flanagan – « toujours excellent quoi qu’il arrive » - remplacera ; à la basse Percy Heath cédera rapidement sa place à Wilbur Little. La batterie était tenue par Elvin Jones. « Il m’a fallu longtemps avant de pouvoir me relaxer avec lui, car il joue aussi fort que Blakey et utilise les rythmes les plus compliqués (7/4, 9/8, 3 / 4). Le tempo est immuable, mais souvent complètement sous-entendu… »

Fasciné, bousculé, Bobby écrira un article sur le sujet, « Les Jones (Elvin et Philly Joe) renouvellent le langage de la batterie » (Jazz Hot, avril 1958). Pour autant, il n’en bouleversera pas de fond en comble son jeu, la polyrythmie pratiquée par Elvin étant parfaitement compatible avec son discours. « J’ai beaucoup travaillé mon instrument et j’ai une sonorité énorme à présent : je crois que ça doit sonner comme Getz, Rollins et Stitt. » L’intensité dans l’énoncé, une puissance sonore nouvelle deviendront autant de facteurs permanents qui feront croire à une conversion aux clichés du Hard Bop. Existe-t-il une vraie solution de continuité entre le discours germanopratin de Jaspar et celui qu’il tient à New York ? La permanence de la ligne mélodique, la constance de ce lyrisme bien spécifique défini par Dave Amram fournissent une réponse. Cette Chose, extrapolation jaspérienne de What Is This Thing Called Love, montre la pérennité de son inspiration, tout comme sa reprise de On a Blues au cours de la séance dirigée aux USA par André Hodeir. Il s’y découvre tout autant en sympathie avec l’esprit de la musique composée par ce dernier que lors de sa première mise en boîte en 1954 en compagnie du Jazz Groupe de Paris. Lorsque, à l’été 1957, Bobby retrouvera à Paris deux de ses anciens partenaires, Sacha Distel et René Urtreger, aucun décalage ne sera perceptible entre eux lorsqu’ils enregistreront quelques morceaux dont une version sublime de Everything Happens to Me.

Jaspar ne faisait que donner une intensité accrue à son discours. Chaque fois que la chose sera possible, il s’assurera de la présence d’Elvin. Ainsi, lorsque six mois après son arrivée à New York, il enregistra un album personnel. « J’ai fait une séance pour Pathé-Marconi en trois fois […] Je joue du ténor, de la flûte et de la clarinette. Tout s’est passé comme sur des roulettes ; technique d’enregistrement incroyable. J’avais écrit la plupart des arrangements, Barry (Galbraith) en a écrit deux. Les deux premières sessions sont, je crois, les plus jazz, jamais je ne me suis entendu jouer comme ça avant. La troisième session est plus raffinée (précision incroyable de la rythmique…) Pas de répétitions, tout à vue. » Ce LP ne sera disponible qu’en France, Espagne et Hollande, pourtant la découverte outre-Atlantique de petits chefs-d’œuvre comme Clarinescapade, Minor Drop ou In a Little Provincial Town, hommage de Bobby à sa ville natale, aurait changé le regard du milieu jazzistique new yorkais.

Elvin sera également présent sur le seul microsillon publié aux Etats-Unis sous le nom de Bobby Jaspar. Une production Riverside consacrant sa rencontre avec George Wallington, auteur de Sweet Blanche et de Before Dawn, titre auquel participait aussi le trompettiste Idrees Sulieman. Les notes de pochette se terminaient de façon péremptoire : « L’un dans l’autre, ce disque doit faire clairement ressortir que Jaspar ne doit bénéficier d’aucune indulgence du fait qu’il soit né ailleurs. Bobby Jaspar est par essence une voix hautement compétente dans le champ du jazz moderne. »

1957 fut pour Bobby l’année des confrontations, un subterfuge utilisé par ses hôtes pour jauger le nouveau venu. Le futur chantre reconnu de la flûte dans le jazz, Herbie Mann sera l’un des premiers à relever le gant. Sur Somewhere, chacun des protagonistes s’exprime tout à tour sur leurs deux instruments de prédilection, le saxophone ténor et la flûte. Une rencontre à fleurets mouchetés.

Le lendemain John Coltrane pénètre à son tour dans le studio d’Hackensack. Quatre compositions de Mal Waldron serviront de supports à « Interplay for 2 trumpets and 2 ténors ». Idrees Sulieman et Webster Young seront les trompettistes, Bobby et Trane qui n’est encore qu’une voix en devenir, les ténors. Aucun des deux ne se décidant à abandonner un poste d’observateur, la confrontation n’en fut pas vraiment une.

Pour terminer l’année, pendant deux semaines Jaspar remplacera au pied levé Sonny Rollins dans le quintette de Miles Davis. Un engagement prestigieux mais à haut risque. Sarcastique, mal embouché, le trompettiste ne manifesta guère d’empathie envers un partenaire qui, passant outre à ses ukases, n’hésitait pas à utiliser la flûte. Sur Nature Boy par exemple. Ce qui subsiste du court passage de Jaspar confirme le jugement d’Alfred Appel Jr. : « Miles ne laisse pas à Bobby toute la latitude qu’il aurait accordé à Rollins, aussi je ne puis me prononcer en ce qui concerne le jeu de Bobby. Ce que j’ai entendu m’a impressionné et paru intéressant. Getz préta une attention particulière au groupe de Miles quand Bobby jouait en solo (9). »

Il faudra attendre le milieu de 1958 pour retrouver Jaspar membre d’une formation régulière (ou presque). Monté en vue d’une tournée européenne, invité au Festival de Jazz de Cannes, le quintette de Donald Byrd lui permit de rejoindre sur la Riviera le Jazz Groupe d’André Hodeir pour interpréter une nouvelle version de son cheval de bataille, On a Blues.

Avec ou sans Donald Byrd, Bobby passa quelques mois en France où l’ensemble fut largement – et exclusivement - enregistré. Au cours d’une séance informelle patronnée par Jef Gilson, Fast Fats montrait que la passion du jeu qui habitait depuis toujours Jaspar n’avait rien perdu de son intensité. À défaut de son audace.

« Stan Getz est à présent écouté dans le monde entier (ce n’est évidemment pas une référence, mais enfin…). Lee Konitz commence à être reconnu comme ouvrant de toutes nouvelles perspectives dans l’art de l’improvisation mais, par contre, Warne Marsh est toujours dans l’ombre… ombre prometteuse car nous serons les premiers à profiter bientôt de son message, j’en suis persuadé (10). » Publiée avant son exil, une déclaration de Bobby qui restera lettre morte. Il ne participa, semble-t-il, à aucune expérience avant-gardiste dans le prolongement de celles qu’il avait conduites à Paris. Les propositions les plus aventureuses introduites par le nonette de Miles Davis restaient d’ailleurs marginales sur la côte est des USA tout comme la musique de Lennie Tristano et de ses disciples. Pendant le séjour de Bobby, entre 1955 et 1961, le pianiste n’enregistra pas un seul disque…

Pour s’imposer dans le paysage jazzistique de la Grosse Pomme, Jaspar fera jouer un autre de ses atouts. L’homme de toutes les expériences s’inclinait devant le flûtiste recherché. Lors de son séjour parisien, sous la houlette de Michel Hausser ou en compagnie de Kenny Clarke, il avait justifié la position exceptionnelle qu’il occupait à ce titre outre-Atlantique.

David Amram : « Il avait un son magnifique qui lui appartenait en propre. Lorsqu’il jouait de la flûte, il était extraordinaire. Non pas tellement en raison de sa virtuosité que de son phrasé et de sa sonorité si particuliers. Avec la façon dont il jouait il vous allait droit au cœur. C’était comme la voix de quelqu’un qui vous fait ressentir quelque chose lorsqu’on l’entend (11). »

Nombre de jazzmen voudront tirer profit de ce don. Ce sera dans des albums où souvent Jaspar n’apparaît qu’au cours de deux ou trois morceaux que l’on trouvera quelques-uns de ces chorus de flûte qui transcendent une interprétation. Qu’elle soit dirigée par Milt Jackson, Helen Merrill, Barry Galbraith – un fidèle depuis l’album gravé pour Pathé-Marconi -, Wynton Kelly, Tal Farlow ou Johnny Rae. Chris Connor, Tony Bennett, Kenny Burrell devenu crooner le sollicitèrent également, tout comme Alexander Sasha Burland, chanteur, animateur producteur et Joe Puma. Le titre des albums patronnés par ces derniers ne laisse guère de doutes sur leur orthodoxie jazzistique, « Swingin’ the Jingles », « Bird Watchin’ » ou « Like Tweet » dont les thèmes prenaient pour points de départ d’authentiques chants d’oiseaux. Jaspar était là en bonne compagnie, côtoyant Cannonball Adderley, Howard McGhee, Hal McKusick, Quincy Jones, Jerome Richardson et quelques autres. Bobby dont l’intransigeance était connue n’avait pas à rougir de sa participation. Il s’agissait certes de séances destinées au grand public mais d’excellente tenue, dans lesquelles il se verra offrir l’occasion de signer quelques arrangements.

De janvier 1960 jusqu’à son retour en Europe au milieu de 1961, les albums auxquels Jaspar participa se compteront sur les doigts d’une main.

Alain Gerber : « On vous invite à la grande table – Jay Jay Johnson, Miles Davis, Hank Jones, Bill Evans, Donald Byrd, un ou deux autres – mais on ne vous retient pas (12) ». Pour ne rien arranger, l’assujettissement de Bobby Jaspar aux stupéfiants – une habitude dont il ne s’était pas débarrassé en traversant l’Atlantique – aggravera encore la situation, contribuant à la détérioration de son état de santé.

En 1958, il avait retrouvé son vieux complice René Thomas sous la houlette de Toshiko Akiyoshi, responsable de l’International Jazz Sextet. Fait rarissime, sur sa composition Sukiyaki, Jaspar s’exprimait au saxophone baryton. Lorsqu’il décida de retrouver l’Europe, ce sera en compagnie du guitariste que Bobby montera une formation après avoir livré une exhibition indigne de lui au festival de Comblain-la-Tour. Gravé à Rome trois mois plus tard, un disque montrait que Jaspar avait retrouvé ses moyens, témoin son délicat rendu de Theme for Freddie à la flûte. La confirmation de cette renaissance se confirmera grâce à Well You Needn’t mis en boîte lors d’une séance dirigée par Chet Baker, tout juste sorti des geôles transalpines.

Faveur exceptionnelle pour un quartette étranger, en janvier 1962 furent engagés au Ronnie Scott’s de Londres, Bobby Jaspar, René Thomas, le bassiste Benoit Quersin et le jeune Daniel Humair. Ce dernier se souviendra d’avoir été stupéfait par la dégradation de l’état physique de Jaspar. Il n’empêche. Le It Could Happen to You interprété à Soho un soir de janvier 1962 compte parmi les plus belles et les plus émouvantes de ses improvisations.

En dépit des conseils prodigués par ses proches, notre homme regagna New York à l’automne. À l’issue d’une opération à cœur ouvert, le voyage de Robert Jaspar trouva son terme au Bellevue Hospital le 4 mars 1963. Il avait trente-sept ans. De tous les hommages qui lui furent rendus, celui rédigé par Pierre Bompar pour Jazz Hip trouvait les mots justes : « Bobby Jaspar était un jazzman et c’est assez rare en Europe pour être signalé. Ce n’était pas, seulement, en effet, un musicien qui jouait du jazz, mais bien un être entièrement baigné de la musique qu’il avait choisi d’offrir, qu’il aimait, qu’il vivait avec intensité. Une intensité presque maladive. Il faisait partie de ces hommes à la sensibilité et à la sincérité exaltantes [...] Il était de la lignée des Boris Vian, se moquant parfois tendrement de lui-même pour nager dans un monde un peu moins conventionnel que celui qui nous est offert chaque jour. »

Alain Tercinet

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Merci à Franck Bergerot, Michel Caron, Dany Lallemand, Alain Gerber, Christophe Henault.

(1) « Bobby Jaspar parle du jazz moderne », Jazz Hot n°96, février 1955. Il s’agit bien entendu de la version de Boplicity interprétée par le Miles Davis Nonet.

(2) Pour suivre et comprendre la carrière de Bobby Jaspar de façon exhaustive, il est absolument indispensable de consulter l’ouvrage de Jean-Pol Schroeder « Bobby Jaspar - Itinéraires d’un jazzman européen (1926 – 1963) », Conseil de la Musique de la Communauté française de Belgique - Pierre Mardaga éditeur, 1997.

(3) Bob Aubert, « Une vedette du Jazz européen Bobby Jaspar », Jazz Hot juillet/août 1951.

(4) Publiés en 2017 seulement, Now’s the Time et Half Nelson témoignent des rencontres entre le quintette de Bobby Jaspar et Lee Konitz accompagné du saxo baryton suédois Lars Gullin. Des extraits d’un 25 cm mis en boîte le 15 janvier 1956, préparé par Marcel Romano mais resté inédit.

(5) Mark Myers, Jazzwax – internet, 9 juin 2010.

(6) comme (1)

(7) André Hodeir « Hommage à Bobby Jaspar », Jazz Hot n°186, avril 1963.

(8) L’orchestre de Walter Gil Fuller, rebaptisé « Gilberto and His Musicabana Orchestra » enregistra au mois de juin 1956 un album « Cha Cha Cha » (Mercury MG20164). Il est impossible de se prononcer sur la présence de Bobby Jaspar.

(9) Alfred Appel Jr. « Trois mois au Birdland », Jazz Hot n°127, décembre 1957. Stan Getz partageait alors l’affiche du Birdland avec le quintette de Miles.

(10) comme (1)

(11) comme (5)

(12) Alain Gerber « Fiesta in Blue - Tome 2 », Editions ALIVE, 1999.

Toutes les citations non référencées proviennent des lettres adressées par Bobby Jaspar à Jazz Hot et publiées.

Textes originaux des citations

Nearly every tenor saxophonist was influenced by Prez then. But Bobby took it in a different direction, melodically. It’s distinctly European, with France and Belgium as his points of reference. Like Django Reinhardt, Bobby was one of the first jazz musicians who came from a totally European background and created his own jazz language and taste.

All in all, this LP should make it quite clear that Jaspar is not to be given any specially lenient evaluation as a non-native oddity. He does need that. Bobby Jaspar can stand on his own as a highly qualified modern jazz voice ».

He had a beautiful sound that was his own. When he played the flute, he was terrific. Not so much as a virtuoso but his phrasing and sound were distinct. The way he played, the music went right to your heart. It’s like a voice that makes you feel something when the person talks.

BOBBY JASPAR

1953-1962, A PRODIGIOUS DECADE

“Belgian saxophonist Bobby Jaspar, who left France for the Pacific almost a year ago, recently made a return visit to the “Old World”: he could be heard on one of the last “Jazz Variétés” shows.” (Jazz Hot, April 1953)

Who could imagine that such a small paragraph would be the prelude to an upturn that made Paris a modern jazz centre to be reckoned with? And all thanks to Bobby Jaspar, a native of French-speaking Belgium with an unbending conception of jazz: “It was when I heard Boplicity that I left the chemistry lab where I’d been working to concentrate entirely on this music that I believed to finally deserve an exceptional aesthetic future.” (1)

On the occasion of the 1949 “Festival Inter‑national du Jazz”, Jaspar had already made a first appearance in the French capital playing with the Bob Shots. They’d shared the bill with the quintets of Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. Born in Liège on February 20, 1926, Bobby was twenty-three at the time and had been playing clarinet since 1942. And then he took up the tenor. (2)

He had been a frequent sight on the scene in Paris—as early as 1951 his talents had earned him a mention in ‘Jazz Hot’ (3)—but on his first visits he didn’t really leave his mark for want of bookings that helped draw attention: he’d replaced players a few times in Django Reinhardt’s band at the Club St Germain, and made the odd appearance at the Bœuf sur le Toit club with Marcel Bianchi. He’d also spent some time in the group led by Jack Dieval… And as for the recording he did—two ballads, Bobby’s Beep and You Are Too Beautiful—it raised hardly any enthusiasm in the reviewer of the record… So Bobby accepted an offer that came in from Tahiti, a dancehall in Papeete called “Les Cols Bleus”. Musically it was a calamity, and because he was both a trained chemist and also a conscientious fellow, he tried to make the best of it by exploring the alleged virtues of shark-liver oil. That new initiative was also a disaster.

Once back in Paris, Bobby noticed that things had changed. Swing tenor—”that lag-along style where you relax instead of hitting everything on the nose”, as Lester Young put it—was everywhere by then. Bobby, who’d adopted the style years before, could now rely on the support of France’s modernists as well as that of his accomplices and compatriots, all of them Belgians: Francy Boland, René Thomas, Benoît Quersin, Christian Kellens and “Fats” Sadi. Bobby Jaspar became the flag-bearer, catalyst and propagator of that style they called “cool”, for want of a better word. In the course of various tours, a number of other musicians would consolidate his legitimacy: Jimmy Raney, Buzz Gardner, the trombonist and arranger Nat Peck, horn player David Amram, baritone saxophonist Jay Cameron, Don Rendell, then the best cool player in England, plus Lee Konitz, Lars Gullin and Chet Baker. (4) In the words of Dave Amram: “Nearly every tenor saxophonist was influenced by Prez then. But Bobby took it in a different direction melodically. It’s distinctly European, with France and Belgium as points of reference. Like Django Reinhardt, Bobby was one of the first jazz musicians who came from a totally European background and created his own jazz language and taste.” (5)

On his first stay in Paris, and in the company of Henri Renaud, Bobby Jaspar had dissected the recordings of the Stan Getz Quintet. He would adopt its formula in choosing a guitarist for a partner. In the album that marked his return, “New Sound from Belgium”, Jimmy Gourley would play this role but soon Sacha Distel replaced him. He was an ideal partner for Bobby, not only musically but also as a human being.

Having been converted to the kind of jazz that Miles Davis’ nonet was producing, Jaspar clearly felt that the writing of it was his concern. He revealed himself to be an arranger of great daring, confronting, in The Nearness of You for example, woodwinds with a horn and tenor. There was no experiment that discouraged him: André Hodeir wrote Paradoxe and Bobby would play it. It was the first dodecaphonic piece written for a jazzman, “a first step towards a widening of the horizons of jazz,” said the sleeve notes. The composition would find an echo in the tenor’s own composition Jeux de Quartes. Bobby had largely contributed to the creation of the Jazz Groupe de Paris ensemble led by Hodeir. “I believe I can say that if France sees a new evolution comparable to the one primed by the Capitol session, then we owe it to André Hodeir.” (6) The two musicians were bound by mutual admiration; André Hodeir would refer to a contribution from Bobby on one of his pieces by saying, “To my eyes, a certain tenor solo on Paraphrase sur Saint-Tropez remains a gem that time has not devalued.” (7)

Fans listening to Christian Chevallier’s first 45rpm record couldn’t believe their ears: on Minor, Bobby Jaspar was playing a flute. Until then, the use of the instrument in jazz had been restricted to a mere handful of musicians—Alberto Socarras, Wayman Carver with Benny Carter and then in Chick Webb’s orchestra, and Harry Klee. In January 1950, when playing with Lionel Hampton in New York, Jerome Richardson would record a flute chorus on There Will Never Be Another You; Frank Wess played flute in March 1954 on a session led by Joe Newman, and did it again two years later with Basie, on The Midgets, a genuine flute manifesto. Out on the West Coast, Bud Shank was using the instrument with Kenton by 1950, and three years later Buddy Collette played the flute with Jerry Fielding’s orchestra. In Paris, in September 1953, it was Gigi Gryce who recorded two titles on flute, accompanied by Henri Renaud. In fact, Bobby Jaspar was merely following a movement; he had a premonition that it held rich opportunities, and he was quite correct.

By now his name was no longer completely unknown to the public. For one thing, his quintet had appeared at the Olympia in Paris and his name appeared on the same poster as the one headed by Juliette Greco. So it’s not surprising that this caption appeared in ‘Music-Hall”, a popular music paper: “On March 24 in Liège, the Belgian tenor saxophonist Bobby Jaspar married pianist and singer Blossom Dearie. Numerous French musicians travelled to Belgium to attend the ceremony.”

Whereas their marriage crumbled rapidly, it still allowed Bobby to make a dream come true: he’d always wanted to face the true jazz life, and preferably in New York. It was an insane dream to have in the mid-Fifties.

And so began the second half of a decade which, seen from his own point of view, was prodigious. In fact, it was an itinerary of which the least you can say is that it was erratic, contrasted, and aroused a good many questions that remained unanswered, since his recordings were only the visible part of the iceberg. Take the collaboration of Bobby Jaspar with the trio of Bill Evans, for example: it left no trace on record, no more than his work in the midst of the twelve-piece group put together by Gil Evans.

It all got off to a most auspicious start. Since Bobby was married to a musician who was an American citizen, he was happy to quickly obtain his union card officialising membership of Local 802, the New York musicians’ syndicate. There was even a cherry on the cake: he’d hardly arrived before bassist Mort Herbert had invited him to play on a record session. And then in June he found himself accompanied by the big band of Walter Gil Fuller. (8). In September, in its article on the annual Critics’ Poll conducted by ‘Down Beat’, the magazine ‘Jazz Hot’ announced that, in the New Stars category, “among the tenor saxes, Bobby Jaspar has placed first, sprinting ahead to beat Charlie Rouse, Buddy Collette, Al Cohn, Frank Foster, Bill Holman and Guy Lafitte.”

“All these musicians like me,” said Bobby, “and they come up to me and say so without the slightest hint of jealousy or fear of losing their place.” Jaspar was in heaven, all the more since J. J. Johnson had hired him to play in his new quintet, allegedly thanks to a recommendation from Miles Davis. In the trombonist’s quintet he found pianist Hank Jones, later replaced by Tommy Flanagan—”Always excellent, no matter what”—alongside bassist Percy Heath, who quickly left the group (he was replaced by Wilbur Little). On drums there was Elvin Jones. “It took me a long time before I could relax with him, because he plays as loud as Blakey and uses the most complicated rhythms (7/4, 9/8, 3/4). The tempo is unflinching, but often entirely suggested…”

Fascinated, shaken to the core, Bobby would write an article on the subject in ‘Jazz Hot’ (April 1958) under the title, “The Joneses (Elvin and Philly Joe) renew the language of the drums.” For all that, he didn’t turn his own playing upside down. The polyrhythm practised by Elvin was perfectly compatible with his own discourse: “I have worked a lot on my instrument and I have a huge sound at present: I think it must sound like Getz, Rollins and Stitt.” The intensity he put into stating a theme, together with a new power behind the sound, would become permanent factors that led people believe he’d converted to the clichés of hard bop. Was there a real gap between the Jaspar of St. Germain-des-Prés and the Jaspar heard in New York? The permanent nature of the melody line, and the constancy of the quite specific lyricism that Dave Amram defined, provide elements of the answer. Cette Chose, which Jaspar extrapolated from What Is This Thing Called Love, shows the permanent nature of his inspiration, as does his reprise of On a Blues on the session that André Hodeir led in the USA. That one shows him to be as much in sympathy with the spirit of Hodeir’s music as he had been on his first recording with the same Hodeir’s Jazz Groupe de Paris in 1954. When Bobby met up again with two of his former partners, Sacha Distel and René Urtreger, in Paris in the summer of 1957, there was no perceptible gap between them in the few recordings they made, among them a sublime version of Everything Happens to Me.

Jaspar merely increased the intensity of his arguments… He took every opportunity to ensure that Elvin Jones was with him, and six months after his arrival in New York he recorded an album under his own name. “I’ve been into the studios for Pathé-Marconi, doing three sessions […] I play tenor, flute and clarinet. Everything went fine… Incredible recording technique… I wrote most of the arrangements, while Barry (Galbraith) did two of them. I think the first two sessions are the most ‘jazz’; I’ve never heard myself play like that before. The third session is more refined (the rhythm section is extraordinarily precise…) No rehearsal, we did it straight off.” The resulting album would only be available in France, Spain and Holland, yet if the other side of the Atlantic had discovered such little masterpieces as Clarinescapade, Minor Drop or In a Little Provincial Town (Bobby’s tribute to his birthplace), it would have changed the way the jazz milieu in New York looked at him.

Elvin would also be present on the only LP that was issued in the USA under Bobby Jaspar’s name. It was a Riverside production that put the seal on his encounter with George Wallington, the writer of Sweet Blanche and Before Dawn, a title that also featured trumpeter Idrees Sulieman. The sleeve notes would conclude, in peremptory fashion, saying, “All in all, this LP should make it quite clear that Jaspar is not to be given any specially lenient evaluation as a non-native oddity. He does need that. Bobby Jaspar can stand on his own as a highly qualified modern jazz voice.”

1957 was a year that saw Bobby in face-to-face situations that increased in scale, a subterfuge used by his hosts to evaluate this newcomer. Herbie Mann, the future High Priest of the flute in jazz, was one of the first to pick up the gauntlet. In Somewhere, the protagonists take it in turn to express themselves on their preferred instruments, tenor saxophone against flute. In their discussion, their remarks are barbed. Only a day later, it was John Coltrane’s turn to go into the studio in Hackensack. Four Mal Waldron compositions formed the canvas for “Interplay for 2 trumpets and 2 tenors.” Idrees Sulieman and Webster Young were the two trumpets, while the tenors were in the hands of Bobby and ‘Trane, the latter a voice gaining in strength. With neither resolved to abandon his observation post, the encounter didn’t amount to a real confrontation.

To end the year, Jaspar would step into the Miles Davis Quintet at a moment’s notice. He was a replacement for Sonny Rollins, a prestigious job but it carried a lot of risk. Sarcastic and rude, the trumpeter showed hardly any empathy with regard to his new partner, who paid little heed to the Tsar’s decrees and didn’t hesitate to play his flute. He did this on Nature Boy for example. The little that remains of Jaspar’s short stay confirms the judgment of Alfred Appel Jr. who said, “Miles doesn’t give Bobby all the latitude he would have given to Rollins, so I can’t make any pronouncement on Bobby’s playing. What I did hear was impressive and sounded interesting. Getz paid particular attention to the group led by Miles when Bobby was taking a solo.” (9)

It would be mid-1958 before Jaspar belonged to a working-group as a regular member (or almost). Donald Byrd’s quintet had been set up in view of a European tour, and when it was invited to appear at the Cannes Jazz festival, it gave Bobby the chance to get back together with André Hodeir and his “Jazz Groupe” on the Riviera, where he played a new version of his favourite On a Blues theme.

With or without Donald Byrd, Bobby spent a few months in France where the group was widely—and exclusively—recorded. In an informal session for Jef Gilson, Fast Fats showed that the passion for playing that had always inhabited Bobby Jaspar had lost none of its intensity, for lack of daring.

“Stan Getz is currently listened to throughout the world (not, obviously, a reference, but anyway…). People are beginning to recognize Lee Konitz as someone opening up new perspectives in the art of improvisation but, on the other hand, Warne Marsh is still standing in the shadows… but the shadows are promising, because we’ll be the first to take advantage of his message soon, I’m convinced of that…” (10) Published before he went into exile, Bobby’s statement would become a dead letter. It would seem that he took no part in any avant-garde experiments that might have followed on naturally from those he conducted in Paris. Besides, the most adventurous proposals introduced by Miles Davis and his nonet would remain marginal on the eastern seaboard in the USA, just like the music of Lennie Tristano and his disciples. During Bobby’s stay there, between 1955 and 1961, the pianist wouldn’t make a single record…

To establish himself in the jazz landscape of the Big Apple, Jaspar would play another of his aces as trumps: the man who loved experiments would give way to the sought-after flautist. During his Parisian stay, whether playing for Michel Hausser or in the company of Kenny Clarke, Bobby had justified the exceptional position he enjoyed on the other side of the Atlantic in this respect. According to David Amram: “He had a beautiful sound that was his own. When he played the flute, he was terrific. Not so much as a virtuoso, but his phrasing and sound were distinct. The way he played, the music went right to your heart. It’s like a voice that makes you feel something when the person talks.” (11)

There were many jazzmen who would take advantage of that gift. And in albums where Jaspar often appeared on no more than two or three titles in this capacity, you can find some flute choruses that transcend “performance”, no matter where he played them: sessions for Milt Jackson, Helen Merrill, Barry Galbraith—one of the faithful ever since the album recorded for Pathé-Marconi—Wynton Kelly, Tal Farlow or Johnny Rae. Chris Connor, Tony Bennett and a Kenny Burrell-turned-crooner would also call on his services, as did Alexander Sasha Burland (singer, presenter, producer) and Joe Puma. The titles of the albums cautioned by these latter names left scarcely any doubt as to their jazz orthodoxy: “Swingin’ the Jingles”, for example, or “Bird Watchin’”, and “Like Tweet”, whose tunes would have their starting-points in genuine birdsong… Jaspar was in good company on those, rubbing shoulders with Cannonball Adderley, Howard McGhee, Hal McKusick, Quincy Jones, Jerome Richardson and a few others. Bobby, whose intransigence was no secret, had no reason to be ashamed of his participation in them. Yes, they were sessions aimed at a large public; but they were excellent, and they also saw Bobby given the chance to write more arrangements.

Between January 1960 and the middle of 1961 when he returned to Europe, the albums in which Bobby took part could be counted on the fingers of one hand. As Alain Gerber said, “They invite you to sit at the high table – Jay Jay Johnson, Miles Davis, Hank Jones, Bill Evans, Donald Byrd, one or two others – but they won’t tie you to the seat.” (12) It didn’t help matters that Bobby Jaspar was addicted to drugs—a habit he hadn’t left behind him when he crossed the Atlantic—and his health deteriorated in consequence.

In 1958 he’d met up with his old pal René Thomas again, for a session led by Toshiko Akiyoshi, who ran the International Jazz Sextet. The rarity here was that Bobby played baritone saxophone on his composition Sukiyaki. When he decided to go back to Europe, it would be in the company of the latter that Bobby set up a group after a poor performance—an exhibition quite unworthy of him—at the Festival of Comblain-la-Tour. Made in Rome three months later, a record showed that Jaspar was again in full possession of his resources, as shown by his delicate reading of Theme for Freddie played on flute. His renaissance would be confirmed thanks to Well You Needn’t, which was recorded at a session led by Chet Baker, who had just been released from jail in Italy…

As an exceptional favour granted to a foreign quartet, in January 1962 the Ronnie Scott club in London extended an invitation to Bobby Jaspar, René Thomas, bassist Benoit Quersin and a young Daniel Humair on drums. Humair remembered how amazed he’d been to see Jaspar’s physical decline. Not that there were any adverse effects on the gig: the version of It Could Happen to You they played in Soho that night in January 1962 counts as one of the most beautiful, most moving improvisations that Jaspar recorded.

Against the advice of those close to him, Bobby went back to New York in the autumn. After he underwent open-heart surgery, the voyage of Robert Jaspar came to an end on March 4, 1963, at Bellevue Hospital. He was thirty-seven. Of all the tributes that were paid to him, the one drafted by Pierre Bompar for Jazz Hip succeeded in hitting the right note: “Bobby Jaspar was a jazzman, and that’s rare enough in Europe to deserve a mention. He was not, in fact, only a musician who played jazz, but indeed a being entirely bathed in the music that he had chosen to love, that he loved, and that he lived with intensity, an intensity that was almost unhealthy. He belonged to those men whose sensibilities and sincerity are exalting [...] He came from a long line of Boris Vians, in that he poked fun at himself, sometimes tenderly, so as to be able to swim in a world that was a little less conventional than the one with which we are presented every day.”

Alain Tercinet

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Thanks to Franck Bergerot, Michel Caron, Dany Lallemand, Alain Gerber, Christophe Henault.

(1) “Bobby Jaspar parle du jazz moderne”, Jazz Hot n°96, February 1955. The reference is of course to the version of Boplicity by the Miles Davis Nonet.

(2) To follow and fully understand Bobby Jaspar’s career it is absolutely indispensable to consult Jean-Pol Schroeder’s “Bobby Jaspar - Itinéraires d’un jazzman européen (1926 – 1963)”, Conseil de la Musique de la Communauté française de Belgique, Pierre Mardaga éditeur, 1997.

(3) Bob Aubert, “Une vedette du Jazz européen Bobby Jaspar”, in Jazz Hot, July/August 1951.

(4) Released only in 2017, Now’s the Time and Half Nelson bear witness to the encounters between the quintet of Bobby Jaspar and Lee Konitz accompanied by the Swedish baritone saxophonist Lars Gullin. Excerpts from a 10” record taped on January 15 1956, prepared by Marcel Romano but unissued.

(5) Mark Myers, Jazzwax – Internet, June 9, 2010.

(6) as (1)

(7) André Hodeir, “Hommage à Bobby Jaspar”, Jazz Hot n°186, April 1963.

(8) The orchestra of Walter Gil Fuller, rechristened “Gilberto and His Musicabana Orchestra”, recorded an album entitled “Cha Cha Cha” (Mercury MG20164) in June 1956. It is impossible to say whether Bobby Jaspar appears on it.

(9) Alfred Appel Jr., “Trois mois au Birdland” in Jazz Hot n°127, December 1957. At the time, Stan Getz was sharing the bill at Birdland with the quintet led by Miles.

(10) as (1)

(11) as (5)

(12) Alain Gerber, “Fiesta in Blue - Tome 2”, Editions ALIVE, 1999.

All the quotes without references are from published letters that Bobby Jaspar wrote to Jazz Hot.

« À l’instar de Django Reinhardt, Bobby a été un des premiers musiciens de jazz qui, venu d’un arrière-plan complétement européen, créa un langage propre au bouquet bien spécifique. » (David Amram)

“Like Django Reinhardt, Bobby was one of the first jazz musicians who came froma totally European background and created his own jazz langage”

(David Amram)

CD 1 – PARIS (1953/1956)

BOBBY JASPAR / HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

1 JEEPERS CREEPERS 3’30

2 STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE 3’35

BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ

3 BLOSSOM 3’46

4 PARADOX 2’30

BERNARD PEIFFER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

5 THERE’S A SMALL HOTEL 3’32

JIMMY RANEY

6 TRÉS CHOUETTE 4’30

BOBBY JASPAR’S NEW JAZZ

7 MORE THAN YOU KNOW 2’43

8 JEU DE QUARTES 2’34

LE JAZZ GROUPE DE PARIS

9 PARAPHRASE SUR SAINT TROPEZ 4’21

BOBBY JASPAR QUARTET

10 NORY’S QUICK 2’27

BOBBY JASPAR ALL STARS

11 THE NEARNESS OF YOU 3’50

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER

ET SON QUINTETTE DE LA ROSE ROUGE

12 MINOR 2’31

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER

ET SON GRAND ORCHESTRE

13 AURA 3’39

DON RENDELL / BOBBY JASPAR

14 A LONG WAY FROM HOME 4’47

DAVE AMRAM / BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET

15 THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT 4’19

CHRISTIAN CHEVALLIER ET SON ORCHESTRE

16 B.S.O.P. 2’51

CHET BAKER QUINTET WITH BOBBY JASPAR

17 HOW ABOUT YOU 4’29

THE BOBBY JASPAR ALL STARS

18 I CAN’T GET STARTED 6’04

19 MEMORY OF DICK 5’36

BOBBY JASPAR / BLOSSOM DEARIE

20 THERE WILL NEVER BE ANOTHER YOU 2’09

CD 2 – NEW YORK / PARIS (1956/57)

BOBBY JASPAR QUARTET & QUINTET

1 CLARINESCAPADE 3’08

2 MINOR DROP 4’26

3 IN A LITTLE PROVINCIAL TOWN 3’37

JAY JAY JOHNSON QUINTET

4 CETTE CHOSE 3’16

ANDRÉ HODEIR

5 ON A BLUES 5’05

HERBIE MANN / BOBBY JASPAR SEXTET

6 SOMEWHERE ELSE 5’57

INTERPLAY FOR 2 TRUMPETS AND 2 TENORS

7 LIGHT BLUE 7’51

JAY JAY JOHNSON QUINTET

8 OLD DEVIL MOON 6’43

MILT JACKSON

9 BAG’S NEW GROOVE 5’59

BOBBY JASPAR

10 BEFORE DAWN 6’12

11 SWEET BLANCHE 5’38

BOBBY JASPAR / SACHA DISTEL

12 SCOTCH HOP 2’48

13 EVERYTHING HAPPENS TO ME 4’19

14 SACHA, BILL ET BOBBY 3’57

MILES DAVIS QUINTET

15 NATURE BOY 4’30

CD 3 – NYC / EUROPE (1958/62)

BARRY GALBRAITH

1 BULL MARKET 2’48

HELEN MERRILL

2 ALL OF YOU 3’31

TOSHIKO AND HIS INTERNATIONAL JAZZ SEXTET

3 SUKIYAKI 6’32

DONALD BYRD / BOBBY JASPAR QUINTET

4 MORE OF THE SAME 6’59

JEF GILSON SEPTETTE

5 FAST FATS 6’07

MICHEL HAUSSER

6 MONSIEUR DE 5’00

BLOSSOM DEARIE

7 CHEZ MOI 3’08

WYNTON KELLY

8 KELLY BLUE 10’49

TAL FARLOW TRIO

9 TELEFUNKY 6’33

THE JOHNNY RAE QUINTET

10 POTLIKKEN BLUES 6’21

THOMAS / JASPAR QUINTET

11 THEME FOR FREDDIE 4’14

CHET BAKER

12 WELL YOU NEEDN’T 6’21

THE BOBBY JASPAR QUARTET

13 IT COULD HAPPENS TO YOU 7’24