- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

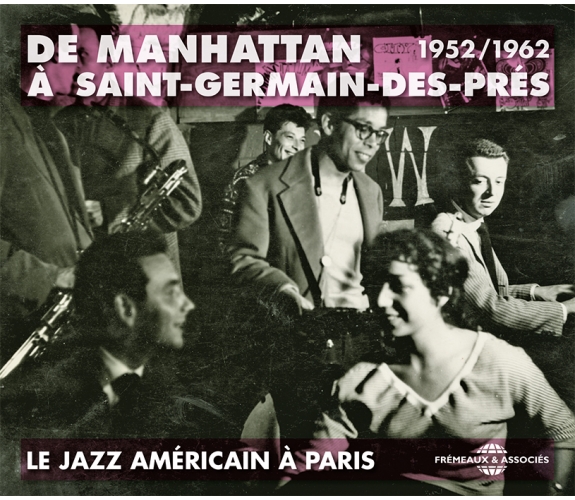

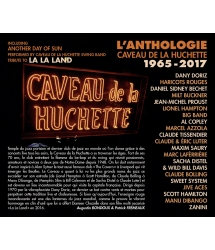

DE MANHATTAN À SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

Ref.: FA5646

EAN : 3561302564623

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 39 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

DE MANHATTAN À SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

DE MANHATTAN À SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

“Saint-Germain achieved as much for music as Montparnasse had for painting after 1918. And not just any music: jazz.” Henri Renaud

LES RICHES HEURES DE LA RIVE GAUCHE

DANY DORIZ • HARICOTS ROUGES • DANIEL SIDNEY BECHET •...

PREMIER CHAPITRE 1954-1961 (UN TEMOIN DANS LA...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Venez donc chez moiHenri Renaud00:04:371952

-

2Mahogany Hall StompHenri Renaud00:03:251953

-

3Record Shop SueyLee Konitz00:03:211953

-

44u001f: 00 P. M.Lee Konitz00:02:461953

-

5Toot's SuiteZoot Sims00:05:531953

-

6The Late Tiny KahnZoot Sims00:04:281953

-

7SchabozzHenri Renaud00:03:121953

-

8Keeping Up With JonesyGigi Gryce00:07:111953

-

9Cover The WaterfrontClifford Brown00:04:041953

-

10BabyClifford Brown00:05:441953

-

11Strictly RomanticClifford Brown00:04:161953

-

12Serenade To SonnyArt Farmer00:02:391953

-

13It Might As Well Be SpringClifford Brown00:05:011953

-

14Lazy ThingsHenri Renaud00:04:271954

-

15Ny's Idea – 1Henri Renaud00:02:151954

-

16Ny's Idea – 2Henri Renaud00:03:181954

-

17Wallington SpecialHenri Renaud00:06:011954

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I'll Remember AprilHenri Renaud00:08:531954

-

2Burt's PadOscar Petitford00:09:441954

-

3Marcel The FurrierOscar Petitford00:05:581954

-

4E-LagOscar Petitford00:02:331954

-

5Escale A VictoriaFranck Foster00:04:421954

-

6Just 40 BarsThe Herdsmen00:04:161954

-

7Palm CafeThe Herdsmen00:05:461954

-

8ThomasiaRené Thomas00:04:231954

-

9SteeplechaseBob Brookmeyer00:06:421954

-

10A Mountain SunsetRoy Haynes00:04:331954

-

11Red RoseRoy Haynes00:03:501954

-

12Minor EncampRoy Haynes00:05:071954

-

13Blue NoteJay Cameron00:03:101955

-

14Wooden Sword StreetJay Cameron00:03:291955

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Takin' Care Of BusinessLucky Thompson00:04:221956

-

2Meet Quincy JonesModern Jazz Group00:03:461956

-

3InfluenceModern Jazz Group00:04:021956

-

4Crazy RhythmZoots Sims00:07:551956

-

5Nuzzolese BluesZoots Sims00:07:261956

-

6Evening In ParisZoots Sims00:03:231956

-

7Daniel's BluesThe Kentonians00:11:501956

-

8Easy GoingLucky Thompson00:04:111956

-

9One For The Boys And UsLucky Thompson00:07:171956

-

10Mac ZootoHenri Renaud00:04:061957

-

11The Tabou TrotHenri Renaud00:03:461957

-

12Don'T Blame MeSonny Criss00:02:481962

-

13Spring Can Really Hang You Up The MostZoot Sims00:03:091961

-

14On The AlamoZoot Sims00:05:411961

FA5646 Manhattan

DE MANHATTAN

À SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

1952/1962

Le Jazz américain à Paris

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD 1

HENRI RENAUD ET SON ORCHESTRE

Jean Liesse (tp) ; Nat Peck (tb) ; Phil Benson (as) ; Sandy Mosse, André Ross (ts) ; Jean-Louis Chautemps (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p, lead) ; Sadi (vib) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Pierre Lemarchand (dm) ; Francy Boland (arr) – Le Bœuf sur le Toit, Paris, February 15, 1952

1. VENEZ DONC CHEZ MOI (Paul Misraki) Blue Star BLP 6831 4’37

solos : Sandy Moss (ts), Sadi (vib), Jimmy Gourley (g), Nat Peck (tb), Sandy Moss (ts), Henri Renaud (p)

HENRI RENAUD ALL-STARS

Jean Liesse (tp) ; Benny Vasseur (tb) ; Georges Barboteu (frh) ; Sandy Mosse, André Ross (ts) ; William Boucaya, Jean-Louis Chautemps (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p, lead) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Benoit Quersin (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) ; Francy Boland (arr) – Paris, April 10, 1953

2. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP (S. Williams) Vogue LD131 3’25

solos : Sandy Moss (ts), Jimmy Gourley (g), Jean Liesse (tp), Jean-Louis Chautemps (bs), Henri Renaud (p)

LEE KONITZ QUARTET

Lee Konitz (as) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g in Record Shop Suey) ; Don Bagley (b) ; Stan Levey (dm) – Paris, September 17, 1953

3. RECORD SHOP SUEY ( L. Konitz) Vogue LD169 3’21

4. 4 : 00 P. M. (L. Konitz) Vogue LD169 2’46

ZOOT SIMS SEXTET

Frank Rosolino (tb) ; Zoot Sims (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Don Bagley (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, September 18, 1953

5. TOOT’S SUITE (B. Holman) Vogue LD170 5’53

6. THE LATE TINY KAHN (T. Kahn) Vogue LD170 4’28

HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

Bobby Jaspar (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) ; Gigi Gryce (arr) – Paris, November 2, 1953

7. SCHABOZZ (G. Gryce) Vogue LD174 3’12

GIGI GRYCE AND HIS BAND

Clifford Brown, Art Farmer, Quincy Jones, Walter Williams, Fernand Verstraete (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland, Bill Tamper, Al Hayse (tb) ; Gigi Gryce, Anthony Ortega (as) ; Clifford Solomon, Henri Bernard (ts) ; Henri Jouot (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Alan Dawson (dm) ; Quincy Jones (arr) – Paris, September 28, 1953

8. KEEPING UP WITH JONESY (Q. Jones) Vogue LD 173 7’11

solos : H. Renaud (intro p), C. Brown/A. Farmer (tp), J. Cleveland (tb), G. Gryce (as), C. Solomon (ts).

CLIFFORD BROWN SEXTET

Clifford Brown (tp) ; Gigi Gryce (as) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, September 29, 1953

9. I COVER THE WATERFRONT (J. Green, E. Heyman) Vogue LD121 4’04

CLIFFORD BROWN / GIGI GRYCE SEXTET

Clifford Brown (tp) ; Gigi Gryce (as) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, October 8, 1953

10. BABY (G. Gryce) Vogue LD175 5’44

11. STRICTLY ROMANTIC (G. Gryce) Vogue LD175 4’16

ART FARMER’S NEW STARS JAZZ

Art Farmer (tp) ; Jimmy Cleveland (tb) ; Anthony Ortega (as) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Marcel Dutrieux (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) - Paris, October 10, 1953.

12. SERENADE TO SONNY (A. Ortega) Vogue EPV1045 2’39

CLIFFORD BROWN QUARTET

Clifford Brown (tp) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Pierre Michelot (b) ; Benny Bennett (dm) – Paris, October 15, 1953

13. IT MIGHT AS WELL BE SPRING (O. Hammerstein, R. Rogers) Vogue LD 179 5’01

HENRI RENAUD - AL COHN QUARTET

Al Cohn (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Gene Ramey (b) ; Denzil Best (dm) – NYC, March 5, 1954

14. LAZY THINGS (H. Renaud) Swing M. 33.322 4’27

15. NY’S IDEA – 1 (H. Renaud) Swing M. 33.322 2’15

16. NY’S IDEA – 2 (H. Renaud) Swing M. 33.322 3’18

HENRI RENAUD BAND

Jerry Hurwitz (tp) ; Jay Jay Johnson (tb) ; Al Cohn (ts) ; Gigi Gryce (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Curley Russel (b) ; Walter Bolden (dm) – NYC, February 28, 1954

17. WALLINGTON SPECIAL (H. Renaud) Swing M 33.327 6’01

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD 2

HENRI RENAUD ALL STARS

Jay Jay Johnson (tb) ; Al Cohn (ts) ; Milt Jackson (vib) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Percy Heath (b) ; Charlie Smith (dm) – NYC, March 7, 1954

1. I’LL REMEMBER APRIL (D. Raye, P. Johnson, G. DePaul) Swing M. 33.320 8’53

OSCAR PETTIFORD ALL-STARS

Kai Winding (tb) ; Al Cohn (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Tal Farlow (g) ; Oscar Pettiford (b) ; Max Roach (dm) – NYC, March 13, 1954

2. BURT’S PAD (H. Renaud) Swing M 33.326 9’44

3. MARCEL THE FURRIER (H. Renaud) Swing M 33.326 5’58

4. E-LAG (G. Mulligan) Swing M 33.326 2’33

FRANK FOSTER QUARTET

Frank Foster (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, April 4, 1954

5. ESCALE A VICTORIA (Varel, Bailly) Vogue LD209 4’42

THE HERDSMEN

Dick Collins (tp) ; Cy Touff (b-tp) ; Dick Hafer, Bill Perkins (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Red Kelly (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, April 23, 1954

6. JUST 40 BARS (H. Renaud) Vogue LD204 4’16

solos : Dick Hafer (ts), Dick Collins (tp), Bill Perkins (ts), Cy Touff (b-tp)

7. PALM CAFE (H. Renaud) Vogue LD204 5’46

solos : Dick Collins (tp), Dick Hafer (ts), Cy Touff (b-tp), Bill Perkins (ts), Henri Renaud (p)

RENÉ THOMAS ET SON QUINTETTE

Buzz Garner (tp) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; René Thomas (g) ; Jean-Marie Ingrand (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Paris, May 5, 1954

8. THOMASIA (R. Thomas, H. Renaud) Vogue LD210 4’23

BOB BROOKMEYER QUINTET

Bob Brookmeyer (v-tb) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Red Mitchell (b) ; Frank Isola (dm) – Paris, June 5, 1954

9. STEEPLECHASE (C. Parker) Vogue LD216 6’42

ROY HAYNES BAND

Barney Wilen (ts) ; Jay Cameron (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jimmy Gourley (g) ; Joe Benjamin (b) ; Roy Haynes (dm) ; Christian Chevallier (arr) – Paris, October 26, 1954

10. A MOUNTAIN SUNSET (C. Chevallier) Swing M33.337 4’33

11. RED ROSE (C. Chevallier) Swing M33.337 3’50

12. MINOR ENCAMP (D. Jordan) Swing M33.337 5’07

JAY CAMERON’S INTERNATIONAL SAX BAND

Barney Wilen, Bobby Jaspar, Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts) ; Jay Cameron (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; André « MacKac » Reilles (dm) ; Christian Chevallier (arr – 14) – Paris, January 10, 1955

13. BLUE NOTE (J. Van Rooyen) Swing M 33.341 3’10

solos : Jay Cameron (bs), Bobby Jaspar, Barney Wilen, Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts)

14. WOODEN SWORD STREET (J. Cameron) Swing M 33.341 3’29

solos : Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts), Jay Cameron (bs), Bobby Jaspar (ts)

DISCOGRAPHIE - CD 3

LUCKY THOMPSON QUINTET

Emmett Berry (tp) ; Lucky Thompson (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Gérard “Dave” Pochonet (dm) – Paris, February 22, 1956

1. TAKIN’ CARE OF BUSINESS (L. Thompson, E. Berry) Ducretet-Thompson 250V024 4’22

MODERN JAZZ GROUP feat. LUCKY THOMPSON

Fred Gérard, Roger Guérin (tp) ; Benny Vasseur (tb) ; Teddy Ameline (as) ; Lucky Thompson, Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts) ; William Boucaya (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p, arr) ; Benoit Quersin (b) ; Roger Paraboschi (dm) – Paris, March 5/7, 1956

2. MEET QUINCY JONES (H. Renaud) Club Français du Disque LP66 3’46

3. INFLUENCE (H. Renaud) Club Français du Disque LP66 4’02

ZOOT SIMS / HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

Jon Eardley (tp) ; Zoot Sims (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Eddie de Haas (b) ; Charles Saudrais (dm) – Paris, March 15, 1956

4. CRAZY RHYTHM (I. Cæsar, J. Meyer, R. Wolfe Kahn) Club Français du Disque LP95 7’55

ZOOT SIMS / HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

Jon Eardley (tp) ; Zoot Sims (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Benoit Quersin (b) ; Charles Saudrais (dm) – Paris, March 16, 1956

5. NUZZOLESE BLUES (J. Eardley, Z. Sims, H. Renaud) Ducretet-Thompson 250V023 7’26

6. EVENING IN PARIS (Q. Jones) Ducretet-Thompson 250V023 3’23

THE KENTONIANS

Dick Mills (tp) ; Carl Fontana (tb) ; Don Rendell (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Curtis Counce (b) ; Wes Ilcken (dm) – Paris, May 4, 1956

7. DANIEL’S BLUES (H. Renaud) Club des Amateurs de Disque CAD3003 11’50

LUCKY THOMPSON & DAVE POCHONET ALL-STARS

Fernand Verstraete (tp) ; Charles Verstraete (tb) ; Jo Hrasko (as) ; Michel de Villers (as, bs) ; Lucky Thompson (ts) ; Marcel Hrasko (bs) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Jean-Pierre Sasson (g) ; Benoît Quersin (b) ; Gérard “Dave” Pochonet (dm) – Paris, May 11, 1956

8. EASY GOING (L. Thompson) Club Français du Disque LP84 4’11

9. ONE FOR THE BOYS AND US (D. Pochonet, L. Thompson) Club Français du Disque LP84 7’17

HENRI RENAUD OCTETTE

Fernand Verstraete (tp) ; Billy Byers (tb, arr -11) ; Charles Verstraete (tb) ; Allen Eager (ts) ; Jean-Louis Chautemps (ts, bs) ; Henri Renaud (p, arr - 10) ; Jean Warland (b) ; Kenny Clarke (dm) – Paris, January 8, 1957

10. MAC ZOOTO (H. Renaud) Ducretet-Thompson 300V027 4’06

11. THE TABOU TROT (B. Byers) Ducretet-Thompson 300V027 3’46

SONNY CRISS QUARTET

Sonny Criss (as) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Michel Gaudry (b) ; Philippe Combelle (dm) – Paris, October 10, 1962

12. DON’T BLAME ME (D. Fields, J. McHugh) Polydor 27 004 2’48

ZOOT SIMS QUARTET

Zoot Sims (ts) ; Henri Renaud (p) ; Bob Whitlock (b) ; Jean-Louis Viale (dm) – Blue Note, Paris, December 1961

13. SPRING CAN REALLY HANG YOU UP THE MOST (L. Wolf, F. Landesman) United Artists UAJ14013 3’09

14. ON THE ALAMO (G. Kahn, J. Lyons) United Artists UAJ14013 5’41

DE MANHATTAN À SAINT GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

1952 / 1962

…et au piano, Henri Renaud

Dès la fin de la 2ème Guerre Mondiale, les jazzmen d’outre-Atlantique sont de retour. Des individualités de premier plan comme Kenny Clarke, Don Byas, Sidney Bechet s’installent sur le vieux continent. D’autres, encore anonymes, séjournent aussi dans la capitale, certains grâce à une bourse du GI Bill qui permet aux anciens combattants de poursuivre leurs études. En sus, il n’est pas un chef d’orchestre venu des États-Unis donner un concert à Paris qui ne voit, une fois le rideau baissé, l’un ou l’autre de ses musiciens s’éclipser, en direction de Saint-

Germain-des-Prés. Une aubaine pour des jazzmen parisiens alors en plein questionnement : ils vien-nent de découvrir que leur musique n’est plus une et indivisible. Quoi de commun entre les tenants du New Orleans Revival, les boppers purs et durs et ceux qui se refusent à faire du passé table rase ?

« Ces musiques cohabitaient, pas toujours très bien. La guerre du jazz était une réalité. Il fallait choisir son camp (1). » Henri Renaud l’avait fait. Pianiste, compositeur, arrangeur, chef d’orchestre, depuis 1946 il avait joué avec la plupart des visiteurs venus des Etats-Unis, Don Byas, James Moody, Roy Eldridge (2). En 1952, à la tête d’un quartette, il développait au Tabou une approche spécifique de la modernité post bop. « À Paris alors nous étions les seuls à jouer une musique où se mêlaient l’influence de Charlie Christian et de Lester Young et celle de Dizzy Gillespie et Charlie Parker (3) ».

L’arrivée en avril 1951 du guitariste Jimmy Gourley, disciple de Jimmy Raney, jointe à la présence du saxophoniste Sandy Mosse dont le jeu puisait ses racines chez Lester Young et Al Cohn, avait été déterminante. Au travers des expériences qu’ils avaient vécues aux USA malgré leur jeune âge et grâce aussi aux quelques disques que contenaient leurs bagages, ils avaient montré à quel point le jazz moderne était redevable au guitariste du Minton’s et à Prez. Au milieu de la confusion stylistique qui régnait dans les caves germanopratines, la voie choisie par Henri Renaud et ses musiciens représentait la forme de jazz la plus novatrice de l’époque. Son extension déboucha sur les premières manifestations probantes d’une collaboration jazzistique franco-américaine bien comprise.

Au début de 1952, Eddie Barclay avait chargé Henri Renaud de réunir un orchestre qu’il enregistrerait en public au Bœuf sur le Toit. « Pour retrouver le « new sound » du Tabou dans l’orchestre du Bœuf, le quartette [ténor, guitare, piano, batterie] fut alors entouré de Jean Liesse, qui, sans le savoir, rappelait Jerry Hurwitz, donnant l’impression, suivant le mot de Gerry Mulligan à propos d’Hurwitz, de « jouer en marchant sur des œufs » ; Nat Peck, venu en Angleterre avec Glenn Miller et qui étudiait alors au Conservatoire de Paris ; Sandy Mosse, arrivé récemment de Chicago et qui vénérait Al Cohn ; Phil Benson, à la fois altiste et attaché culturel à l’ambassade américaine ; Jean-Louis Chautemps qui jouerait du baryton ; deux musiciens belges, habitués du Tabou, Sadi et Benoît Quersin (4). » Pour interpréter Venez donc chez moi, cinq français, deux belges et quatre américains. Une association qui, jusqu’alors, n’avait guère connu qu’un précédent nettement plus restreint lors de l’enregistrement à Paris de la Period Suite de John Lewis.

Par son arrangement de la composition de Paul Misraki, Francy Boland avait su préserver dans le cadre d’une moyenne formation l’esprit du jazz joué au Tabou. Il récidivera un an plus tard à partir d’un thème cher à Louis Armstrong, Mahogany Hall Stomp, destiné à l’album « Modern Sounds : France ». Même soin apporté à l’écriture - les échanges cuivres / ténors y sont parfaitement conçus – avec une différence perceptible dans le son d’ensemble due à l’apparition d’un cor et au doublement des saxophones baryton. Si la présence de Sandy Mosse et Jimmy Gourley, les seuls américains en lice, garantissait la continuité d’une certaine appréhension du jazz, elle n’était plus de leur seul fait : tous les participants parlaient d’une même voix. Jean-Louis Chautemps, Jean Liesse, « une sorte de Chet Baker avant l’heure » selon Henri Renaud qui, lui-même, jouait trente-deux mesures parfaites. « Tout ce que les musiciens européens ont appris de nos boppers itinérants est apparent dans un disque Contemporary « Modern Sounds : France » présentant Henri Renaud » écrivait Gary Kramer dans le numéro de The Billboard du 18 septembre 1953. De son côté Charles Delaunay concluait ainsi les notes de pochette de l’édition américaine : « Ce disque Long Playing montre de manière convaincante la vitalité de notre jeune génération de musiciens qui, nous l’espérons, remettra bientôt le jazz français à la position qu’il occupait avant-guerre. » Un vœu qui deviendra réalité.

Si les moyennes formations réunies par Henri Renaud pour « New Sound at the Bœuf sur le Toit » et « Modern Sounds : France » consacraient de façon concluante les vertus de la mixité jazzistique franco-américaine, elles ne furent qu’éphémères. Pour différentes raisons, commer-ciales entre autres, les rencontres entre visiteurs et autochtones prendront une forme moins éla-borée. Les séances d’enregistrement se program-meront sur le moment, en fonction des venues de musiciens disponibles. Grâce à ses talents d’accompagnateur hors-pair et d’organisateur, Henri Renaud sera à nouveau partie prenante dans une série d’albums qui survolera les grandes confrontations intercontinentales du jazz moderne.

Le 18 septembre 1953, l‘orchestre de Stan Kenton doit donner un concert à l’Alhambra. Le jour même, trois de ses membres, Don Bagley, Stan Levey et Lee Konitz, franchissent les portes du studio de la rue Jouvenet où les attendent Henri Renaud et une vieille connaissance de Konitz remontant à leurs études à Chicago, Jimmy Gourley. Dans l’urgence sont mis en boîte Record Shop Suey et 4 : 00 P. M., deux variations sur, respectivement, All the Things You Are et These Foolish Things. Des versions déroutantes pour l’époque. On pourra lire dans Jazz Hot : « Le sens rythmique de Lee Konitz est déconcertant. Il joue sans se soucier, semble-t-il du tempo, et il faut s’accoutumer longuement à ce style avant de saisir les rapports qui existent entre le jeu de la section rythmique et celui de Konitz ».

Le lendemain, c’est au tour de Zoot Sims, Frank Rosolino et à nouveau Don Bagley - Stan Levey a cédé son tabouret à Jean-Louis Viale - de rejoindre le même studio (5). À l’occasion de cette rencontre, s’instaura d’emblée, entre Zoot et Henri Renaud, une complicité évidente au long de Toot’s Suite et de The Late Tiny Kahn où Frank Rosolino fait merveille.

Huit jours plus tard, le grand orchestre de Lionel Hampton débarque. Sitôt le concert terminé au Palais de Chaillot, les jeunes loups de la formation se précipitent au Tabou. L’un d’eux, Gigi Gryce alors parfaitement inconnu, aura la surprise de sa vie : on y jouait l’une de ses compositions. En effet, venait souvent faire le bœuf dans la cave de la rue Dauphine un jeune guitariste, Sacha Distel. Au cours d’un stage aux USA, il avait sympathisé avec Jimmy Raney qui lui avait présenté Stan Getz. Ce dernier avait offert à Sacha quelques partitions de thèmes figurant à son répertoire qui, en retour, entrèrent dans celui de l’orchestre d’Henri Renaud ; Schabozz, signé Gigi Gryce, en faisait partie.

« C’était en septembre au Tabou où je travaillais alors en trio avec Jimmy Gourley et Jean-Louis Viale. Gigi Gryce et Art Farmer jouaient à nos côtés tandis que Brownie était installé à la première table devant l’orchestre. Après quelques chorus de Gigi et Art, Brownie « démarra » et vit toutes les têtes se tourner de son côté. Complètement ébahies. Il y avait de quoi : ce n’est pas tous les jours que l’on découvre à Paris un trompettiste inconnu qui, en quelques notes, vous montre clairement qu’il est de la classe de Dizzy et Miles. » (6)

Sur le champ, l’un des directeurs de Vogue, Léon Cabat, décida avec Henri Renaud d’essayer de mettre sur pied une séance d’enregistrement. Ce qui n’était pas une mince affaire car était stipulé dans le contrat des musiciens l’interdiction absolue de mettre les pieds dans un studio sans leur employeur, sous peine de sanctions. Et Gladys Hampton, l’épouse de Lionel ainsi que le manager de l’orchestre veillaient au grain. Heureusement les hôtels parisiens ont des sorties dérobées…

Le 29 septembre fut mis en boîte Keeping Up with Jonesy, composé et arrangé par Quincy Jones, qui nécessitait pas moins de… seize exécutants. Dix américains et six français. Son exécution qui, fait rare en ces débuts du LP, dépassait les sept minutes, tenait quelque peu du tour de force. Une gageure relevée haut la main.

Au fil des jours s’enchaîneront quelques huit séances, toutes, ou presque, mettant légitimement en valeur l’exceptionnel talent de Clifford Brown. Sur des standards comme I Cover the Waterfront et It Might as Well Be Spring gravé à la dernière minute ou des originaux signés Gigi Gryce, Baby et Strictly Romantic. Par contre Serenade to Sonny, dû à Anthony Ortega, donnait la parole à Art Farmer qui n’avait encore gravé sous son nom que quatre morceaux.

Repris aux USA par Blue Note, les enregistrements parisiens ne passèrent pas inaperçus, non plus que la part essentielle qu’y avait pris Henri Renaud. Son l’album « New Sounds : France » venant d’être publié par Contemporary, à la fin de l’année 1953, il décida de traverser l’Atlantique. Charles Delaunay lui suggéra de poursuivre dans les studios américains le même travail qu’en France. Juste retour des choses, Saint Germain-des-Prés s’inviterait à Manhattan.

« Sur n’importe quel morceau, aussi compliqué soit-il harmoniquement, Al improvise immédiatement une ligne mélodique dont le déroulement est si simple et si logique qu’on pourrait en faire un thème. Cette subtilité d’ailleurs va de pair avec sa force expressive (7). » Henri Renaud n’avait jamais caché son admiration pour Al Cohn qui, pour l’occasion, deviendra son interlocuteur privilégié. En quartette sur Lazy Things et Ny’s Idea 1 et 2, deux improvisations libres sur le blues en mineur, au sein d’un septette en compagnie de Jerry Hurwitz, Gigi Gryce et Jay Jay Johnson pour Wallington Special ou de Milt Jackson et de nouveau Jay Jay sur I’ll Remember April (8).

Henri Renaud fut invité par Leonard Feather à une séance dirigée par Oscar Pettiford, dans laquelle il retrouvait une nouvelle fois Al Cohn mais aussi Kai Winding, Tal Farlow et Max Roach. Il avait amené avec lui trois thèmes. E-Lag, une composition que Gerry Mulligan lui avait offerte et deux originaux, Burt’s Pad en hommage au graphiste Burt Goldblatt et Marcel the Furrier saluant un ami habitué du Tabou, photographe et négociant en fourrure, Marcel Fleiss. La moitié du répertoire.

Tal Farlow, qui ne lisait pas la musique, apprit d’oreille le pont de Burt’s Pad qui lui était dévolu. Un morceau qui inspira à Al Cohn l’un de ses plus beaux chorus. Alun Morgan expliquera pourquoi : « Il y a dans la façon d’écrire d’Henri Renaud une grâce mélodique qui est comme un écho du style d’improvisation de ses héros, dont la liste comprendrait les pianistes George Wallington, Al Haig, Art Tatum et Jimmy Rowles, mais aussi les saxophonistes Al Cohn et Zoot Sims (9). »

Non seulement, en tant que maître d’œuvre, Henri Renaud avait prolongé dans la Grosse Pomme les séances parisiennes – une grande première – mais il avait introduit de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique un répertoire original. Burt’s Pad sera repris par George Wallington et Jimmy Rowles consacrera un album entier à ses compositions.

À Paris, les séances dans l’urgence restant d’actualité, Frank Foster en profita pour signer son premier album personnel. Au cours d’une séance enchaînant sur une nuit blanche – elle débuta à 9 heures du matin –, le nouvel espoir du ténor justifia les espérances que Count Basie avait mis en lui. De façon assez inattendue, il improvisa sur une chanson française due aux duettistes André Varel et Charly Bailly qu’interprétait Jacqueline François, Escale à Victoria. Il est vrai qu’il en existait une version américaine.

Sans plus de préméditation, Bob Brookmeyer, Red Mitchell, Frank Isola (le Gerry Mulligan Quartet sans son chef) se joindront à Jimmy Gourley et Henri Renaud pour une rencontre que ce dernier jugera décevante. Pourtant, sur Steeplechase exposé par Brook avec un contrechant de Jimmy Gourley, Red Mitchell et Henri Renaud lui-même apportaient un regard nouveau sur la composition de Charlie Parker.

Autre spécialité importée des USA, les disques offrant la possibilité de vivre chez soi l’équivalent de ce qu’entendaient quelques privilégiés entassés dans une cave de St Germain-des-Prés. « The Third Herdsmen Blow in Paris » donnait à entendre cinq membres de l’orchestre Woody Herman faisant le bœuf en compagnie de Jean-Louis Viale et d’Henri Renaud sur deux originaux de ce dernier, Just 40 Bars et Palm Café. Dick Collins, ancien élève de Darius Milhaud qui avait appartenu aux Be Bop Minstrels parisiens à la fin des années 1940 ; Cy Touff rare spécialiste de la trompette basse ; Dick Hafer et Bill Perkins, deux des meilleurs représentants de la seconde génération de « Brothers ; Red Kelly, solide contrebassiste qui, peu après, rejoindra les formations de Maynard Ferguson et de Stan Kenton.

Ce seront trois membres de ce dernier orchestre, un batteur néerlandais, un trompettiste américain de passage et un pianiste français qui s’affronteront, deux ans plus tard entre cinq et huit heures du matin, sur Daniel’s Blue. D’un côté Carl Fontana l’un des meilleurs trombonistes modernes, Don Rendell ténor lestérien venu d’Angleterre, Curtis Counce bassiste omniprésent sur la West Coast. De l’autre Wes Ilcken et Dick Mills, ancien partenaire de Brew Moore qui se produisaient au Caméléon dans la formation de… Henri Renaud. Sans effort, ressuscitait en studio l’essence même de la jam session avec ses réussites, ses surprises mais aussi ses approximations.

Le séjour prolongé de certains visiteurs permettait que soient planifiées les séances dans lesquelles ils étaient partie prenante. Ainsi, à l’attention de Roy Haynes et de Joe Benjamin, Christian Chevallier composa A Mountain Sunset et Red Rose dont il signa également les arrangements, tout comme celui de Minor Encamp. Une composition dont Duke Jordan avait donné la partition à Henri Renaud qui, à New York, lui avait permis de graver son premier album en trio. Parmi les interlocuteurs des deux accompagnateurs de Sarah Vaughan, le tout jeune Barney Wilen et, au baryton, Jay Cameron. Un saxophoniste américain installé en Europe depuis sept ans qui, au bout de ce laps de temps, se verra offrir l’occasion de signer son premier album personnel.

À cette fin, il s’entourera de trois ténors et d’une rythmique. Une instrumentation inusitée – en forme d’hommage à la fameuse section de saxes des « Brothers » – mise en valeur dans Wooden Sword Street et Blue Note. Jazz Magazine détestera contrairement à Boris Vian: « Voici un microsillon de classe et de composition originale, ce qui fait bien plaisir. » La vérité était évidemment de son côté.

Autre visiteur, fugitif celui-là, Charles « Buzz » Gardner. Une fois terminé son service militaire dans l’US Army en Europe, il se rendit à Paris le temps de montrer dans Thomasina que sa sonorité à la trompette se mariait de façon idéale à celle de la guitare de René Thomas. De retour aux USA, il changera quelque peu de registre sous la houlette de Frank Zappa et de Captain Beefheart.

Au mois de mars 1956, l’Olympia présenta un spectacle avec Jacqueline François en tête d’affiche et le sextette de Gerry Mulligan en vedette américaine (dans les deux sens du terme). Zoot Sims en faisait partie, l’occasion rêvée pour remettre le couvert.

La veille de la séance, après la représentation

de l’Olympia, Zoot se rendit dans un studio accompagné du trompettiste Jon Eardley, autre membre du sextette. Quelques points de détail demandaient à être précisés avec le trio d’Henri Renaud. À la demande des musiciens, les magnétophones tournèrent, conservant ainsi un témoignage d’improvisateurs jouant en toute liberté sur Crazy Rhythm. Benoît Quersin remplaçant Eddie de Haas, les cinq partenaires gravèrent le lendemain un Nuzzolese Blues magistral, Zoot Sims se réservant Evening in Paris. Une petite merveille de lyrisme retenu qui ne sera égalée qu’en 1961 par Spring Can Really Hang You Up The Most. On the Alamo gravé lors la même session donnait une véritable leçon de swing (10).

Si Zoot enregistra à plusieurs reprises dans la capitale, il n’y séjourna jamais très longtemps. Contrairement à ses confrères, Allen Eager, Lucky Thompson et Sonny Criss. Ayant pris ses distances avec la musique, persuadé de faire ainsi fortune Allen Eager avait entrepris de convertir la Riviera à l’usage des machines à ice-cream. Il déchanta très rapidement et revint vers ce qu’il savait le mieux faire, le jazz et, durant les quelques mois qu’il passa dans la capitale, on le vit croiser le fer au Club Saint Germain avec Barney Wilen. Allen Eager participa également à divers albums dont l’un des plus intéressants l’associa à deux de ses compatriotes, Kenny Clarke et Billy Byers, au sein d’un octette franco-américain. Pour l’occasion, Billy Byers composa et arrangea The Tabou Trot, un hommage à la cave de la rue Dauphine qui n’avait rien perdu de son aura. Henri Renaud lui, préféra saluer son ami Zoot Sims avec Mac Zooto,

La venue en Europe d’Eli Lucky Thompson servit de catalyseur à de multiples initiatives. Pour sa première séance à Paris, il croisa sans façon le fer avec Emmett Berry sur Takin’Care of Business – un curieux blues en majeur – mais, quinze jours plus tard, il participait à une entreprise plus ambitieuse comme en témoignent Meet Quincy Jones et Influence. Bien des années plus tard, sur son site JazzWax, Mark Myers écrira : « En 1956, la scène du jazz français foisonnait de musiciens locaux et américains ; un contingent de jazzmen autochtones était fortement influencé par l’approche sensuelle de l’harmonie pratiquée par Quincy Jones et Gigi Gryce, toutes deux découlantant de Tadd Dameron […] Lorsque Thompson arriva à Paris en 1956, presque immédiatement fut formé un tentette dans lequel Henri Renaud tenait le piano et signait les arrangements […] Le matériel, exceptionnel, est resté aussi frais qu’au premier jour et pour moi l’album compte parmi ceux de Lucky Thompson que je préfère. »

Une instrumentation similaire sera réunie par le batteur Gérard « Dave » Pochonet autour d’un Lucky Thompson impérial. Easy Going donnait à entendre Michel de Villers au baryton et l’excellent guitariste Jean-Pierre Sasson présent également dans One for the Boys and Us.

S’étant rendu à Paris sur un coup de tête, en sortant de son hôtel rue St Benoît Sonny Criss croisait souvent Marcel Romano, directeur artistique du Club Saint Germain. Le croyant en vacances, ce dernier se gardait bien de l’importuner… au grand dam de l’intéressé. Un quiproquo qui finira par se dénouer. Sonny Criss jouera au Chat qui Pêche et franchira la porte d’un studio d’enregistrement. « Henri Renaud qui travaillait avec moi était en relation avec les firmes Polydor et Brunswick ; il mit sur pied quel-ques séances. Nous avons fait plusieurs 45 t EP et un album avec Philippe Combelle, Michel Gaudry, Henri et Georges Arvanitas. » Don’t Blame Me y figurait.

« Au début des années cinquante, j’ai eu la chance de participer à de nombreuses sessions en com-pagnie de musiciens américains de passage à Paris tels Lee Konitz, Zoot Sims, Clifford Brown, Quincy Jones, Art Farmer, Roy Haynes (11). » Au cours de la décennie 1952 – 1962, jazzmen américains et jazzmen français construisirent autour d’Henri Renaud un pan de l’histoire du jazz hexagonal. D’autres grandes rencontres se produiront encore mais rien ne sera plus tout à fait pareil.

Alain Tercinet

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nicolas Benies, « Entretien avec Henri Renaud », Internet

(2) Certaines discographies indiquent la présence d’Henri Renaud sur deux morceaux de James Moody, You Go to My Head et Don’t Blame Me datés 1958. Ces interprétations remontent en fait à 1948 ou 1950. La très mauvaise qualité du son ne permet pas d’identifier avec certitude le pianiste.

(3) Henri Renaud, « Le retour de Saturne, » Jazz Magazine n° 521, décembre 2001.

(4) Notes de pochette de « New Sound at the Bœuf sur le Toit », réédition Fresh Sound du Blue Star BLP 6831.

(5) De nombreuses discographies datent cette séance du 18 novembre alors que Zoot Sims et Frank Rosolino, toujours membres de l’orchestre Stan Kenton, étaient à nouveau aux Etats-Unis.

(6) « Adieu Brownie… », Jazz Magazine n° 20, septembre 1956.

(7) Kurt Mohr, « À propos d’Al Cohn, une interview d’Henri Renaud », Jazz Hot n° 104, novembre 1955.

(8) Les trois séances new-yorkaises furent publiées sous la forme de 4 LP 25 cm Swing intitulés « Henri Renaud nous rapporte des USA » et « Henri Renaud’s U. S. Stars ». Leurs couvertures étaient illustrées par Charles Delaunay. Au fil des rééditions, pour des raisons commerciales, le nom du maître d’œuvre disparaitra au profit de sidemen jugés plus vendeurs. Ce qui irrita fort Milt Jackson mis en avant par ce stratagème.

(9) Livret de « Jimmy Rowles & Michael Moore – Profile, The Music of Henri Renaud » Columbia.

(10) Cette séance fut enregistrée spécialement devant un public d’invités. En effet Zoot se produisit au Blue Note à partir le 27 novembre avec le trio de Kenny Clarke, alors que, au cours de cette séance, ses accompagnateurs sont Bob Whitlock, alors résidant à Paris, Jean-Louis Viale et Henri Renaud. Une formation qui, avec Zoot, assurait la musique d’un court-métrage de 18 minutes, « Flash », tourné au Blue Note par le cinéaste underground Allan Zion. Il retraçait les errances d’un junkie interprété par Gary Goodrow qui avait incarné, tant sur scène qu’à l’écran, l’un des personnages de « The Connection ». « Flash »qui eut maille à partir avec la censure semble avoir disparu.

(11) Matthieu Jouan « Henri Renaud – Le jubilé du jazz », Citizen Jazz

FROM MANHATTAN TO SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS

1952 / 1962

…with, on piano, Henri Renaud

American jazzmen crossed the Atlantic again as soon as the Second World War was over. Top flight inviduals like Kenny Clarke, Don Byas and Sidney Bechet even settled on the Old Continent, while others who were still anonymous merely stayed in the French capital, some of them thanks to the GI Bill, which financed ex-military personnel seeking to pursue their studies. To cap it all, there wasn’t a single bandleader — over from the States to play a concert in Paris — who hadn’t experienced the sight of one or other of his musicians disappearing towards Saint-Germain-des-Prés once the curtain fell… For Parisian jazzers, who were full of questions, it was a godsend: they’d just discovered that their music was no longer a single, indivisible form. What could there possibly be in common between supporters of the New Orleans Revival, hardline boppers, and those who steadfastly refused to forget the past had existence?

“These music forms were cohabiting, and not always very well. The jazz war was a reality. One had to choose sides.”(1) Henri Renaud had chosen his. Pianist, composer, arranger, bandleader… Since 1946, Henri Renaud had played with most of those American visitors, from Don Byas to James Moody and Roy Eldridge. (2) In 1952, at the Tabou club and fronting a quartet, he developed a specific approach to post-bop modernism. “In Paris at that time we were the only ones playing music where the influence of Charlie Christian and Lester Young mingled with that of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker.” (3) The arrival of guitarist Jimmy Gourley in April 1951 (he was a disciple of Jimmy Raney), together with the presence of saxophonist Sandy Mosse, whose playing had roots in Lester Young and Al Cohn, was decisive. Through their experience gained in the USA (despite their youth), and also thanks to a few records they had in their suitcases, Gourley showed exactly how much of a debt modern jazz owed to Prez and that guitarist from Minton’s. In the midst of all the stylistic confusion reigning in the cellars of Saint-Germain, the path chosen by Henri Renaud and his musicians represented the most innovative jazz played in that period. Renaud et al paved the way for the first conclusive manifestations of Franco-American jazz collaborations.

Early in 1952, Eddie Barclay asked Henri Renaud to put together an orchestra for a “live” recording he wanted to do at the Bœuf sur le Toit. “To reproduce the ‘new sound’ of the Tabou with the Bœuf band, the quartet [tenor, guitar, piano, drums] was surrounded by: Jean Liesse who, unknowingly, reminded people of Jerry Hurwitz and so gave the impression, to quote Gerry Mulligan on the subject of Hurwitz, of ‘playing like walking on eggs’; Nat Peck, who’d gone to England with Glenn Miller and was then studying at the Paris Conservatory; Sandy Mosse, who’d just come from Chicago and worshipped Al Cohn; Phil Benson, who not only played alto but was Cultural Attaché for the American Embassy; Jean-Louis Chautemps, who was there to play baritone; and two Belgian musicians who were Tabou club regulars, namely Sadi and Benoît Quersin.” (4) So five Frenchmen, two Belgians and four Americans played Venez donc chez moi. The association only had one (much smaller) precedent: the recording in Paris of John Lewis’ Period Suite.

With his arrangement of Paul Misraki’s composition, Francy Boland had managed to preserve the spirit of jazz as played at the Tabou, but in the context of a medium-sized ensemble. A year later he’d do so again, this time when he took a tune that was dear to Louis Armstrong, Mahogany Hall Stomp, and arranged it for the album called “Modern Sounds: France”. The same care was taken over the writing — the brass/tenor exchanges he conceived are perfect — with a perceptible difference in the ensemble sound due to the appearance of a horn and twice the number of baritone saxophones. While the presence of Mosse and Gourley, the only Americans involved, guaranteed continuity in a certain understanding of jazz, they weren’t the only ones responsible: all the participants spoke the same language. Jean-Louis Chautemps, Jean Liesse, “a kind of Chet Baker before his time” according to Henri Renaud, who was also present and plays thirty-two perfect bars. “How much the European musicians have learned from our itinerant bopsters is revealed in a Contemporary album featuring Henri Renaud entitled ‘Modern Sounds: France’,” wrote Gary Kramer in Billboard’s September 18 issue (1953). As for Charles Delaunay, in his sleeve-notes for the American release he concluded, “This Long Playing record convincingly proves the vitality of the young generation of French musicians, who will soon, we hope, bring French Jazz back to the position it enjoyed before the last World War.” His hope would become a reality...

While the midsize groups put together by Henri Renaud for “New Sound at the Bœuf sur le Toit” and “Modern Sounds: France” conclusively sanctioned the virtues of a Franco-American social mix, they were in fact only ephemeral. For different reasons, some of them commercial, meetings between the natives and their visitors would take on a less elaborate form, with recording-sessions booked at the last minute depending on those visitors who were available. Thanks to his peerless talents as an accompanist and organizer, Henri Renaud would again be involved in a series of albums that stand head and shoulders above some of the other intercontinental confrontations in modern jazz.

On September 18, 1953, the Stan Kenton orchestra was due to play a Paris concert at the Alhambra. That same day, three of its members — Don Bagley, Stan Levey and Lee Konitz — went through the door of a studio on the rue Jouvenet, where Henri Renaud was waiting for them with an old acquaintance of Konitz dating from the days when they were both students in Chiago: Jimmy Gourley. They hastily recorded Record Shop Suey and 4:00 P.M., two variations on All the Things You Are and These Foolish Things respectively. For the period, these versions were alarming. In “Jazz Hot”, people could read, “The sense of rhythm in Lee Konitz is disconcerting. He seems to play with no care for the tempo, and you have to be accustomed to this style long before you can understand the rapports that exist between the rhythm section’s playing and that of Konitz.”

The next day it was Zoot Sims’ turn, along with Frank Rosolino and again Don Bagley — Stan Levey had left his seat to Jean-Louis Viale — to go into the same studio.(5) Right from the start it was the occasion for Zoot and Henri Renaud to develop an obvious empathy in Toot’s Suite, and also in The Late Tiny Kahn where Frank Rosolino plays marvellously.

Eight days later, Lionel Hampton’s big band turned up. As soon as their gig at the Palais de Chaillot finished, the young go-getters in the band rushed over to the Tabou. One of them, Gigi Gryce, was then a total unknown and he had the surprise of his life when he heard one of his own compositions being played… but then he didn’t know that this jazz cellar on the rue Dauphine was a place where the young guitarist Sacha Distel regularly went to jam. Onstage in America he’d become friends with Jimmy Raney, who’d introduced him to Stan Getz. Stan had given Sacha a few of the scores in his book, and these, in turn, found their way into the repertoire of Henri Renaud’s band. One of them was this Gigi Gryce tune, Schabozz.

“It was in September at the Tabou, when I took a trio there with Jimmy Gourley et Jean-Louis Viale. Gigi Gryce and Art Farmer were playing alongside us, with Brownie at the first table in front of the band. After a few choruses from Gigi and Art, Brownie ‘took off’, and all heads turned to look at him. They were all astounded. And so they should be: it’s not every day that you find a trumpeter in Paris who, in just a few notes, clearly shows he has the class of Dizzy and Miles.” (6) Right then and there, Henri Renaud and one of the staff at the Vogue label, Léon Cabat, decided to try and set up a recording session. And that was quite complicated, as the musicians’ contracts expressly forbade them from setting foot in a studio without their employer, and there were penalties if they did so. And that wasn’t all: Gladys Hampton, Lionel’s spouse and also the band’s manager, was keeping a watchful eye on everyone. It was a good thing the hotels in Paris had hidden exits…

On September 29 they recorded Keeping Up with Jonesy, composed and arranged by Quincy Jones, which called for no fewer than sixteen instrumentalists. Ten Americans and six French musicians. Playing this tune — it lasts over seven minutes, a rarity in those early LP days — amounts to a tour de force but they took up the challenge magnificently. As the days went by, the sessions came one after another, eight in all, and almost every one of them legitimately highlighted the exceptional talent of Clifford Brown, whether they were playing standards like I Cover the Waterfront or It Might as Well Be Spring (recorded at the last minute), or original tunes written by Gryce such as Baby or Strictly Romantic. Anthony Ortega’s tune Serenade to Sonny, on the other hand, was a feature for Art Farmer, who’d so far only recorded four pieces under his own name.

When Blue Note picked up these Parisian tapes for American release they didn’t go unnoticed, no more than the essential role that Henri Renaud played in them. His album “New Sounds: France” had just been released by Contemporary, at the end of 1953, and Renaud decided to cross the Atlantic also. Charles Delaunay suggested that he might care to pursue the same aims in America’s studios, and continue the work he’d begun in France: Saint Germain-des-Prés would invite itself to Manhattan.

“On any piece [you give him], no matter how complicated it is harmonically, Al can immediately improvise a melody line that unwinds so simply and so logically that you could make a tune out of it. That subtlety, by the way, goes hand in hand with the strength of his expression.”(7) Renaud had never hidden his admiration for Al Cohn, and now the tenor had occasion to enjoy the privilege of partnering him in conversation, whether in a quartet setting on Lazy Things and Ny’s Idea 1 and 2, two free improvisations on a minor key blues, or else playing in a septet, together with Jerry Hurwitz, Gigi Gryce and Jay Jay Johnson, on Wallington Special, or with Milt Jackson and Jay Jay again on I’ll Remember April.(8)

Leonard Feather invited Henri Renaud to a session led by Oscar Pettiford, where he met up with Al Cohn again, but also Kai Winding, Tal Farlow and Max Roach. With him he’d brought three tunes: E-Lag, a composition that Gerry Mulligan had given him, and two of Henri’s own tunes, Burt’s Pad (a tribute to the graphic artist Burt Goldblatt) and Marcel the Furrier, which was a salute to a friend of his (another regular at the Tabou), namely the photographer (and incidentally furrier) Marcel Fleiss. The tunes made up half the repertoire on the session. Tal Farlow, who didn’t sight-read, learned to play the bridge in Burt’s Pad by ear. The same piece inspired Al Cohn to play one of his most beautiful choruses, and critic Alun Morgan explained why: “There is a melodic grace to Renaud’s writing which echoes the improvisational styles of his heroes, a list of whose names would include the pianists George Wallington, Al Haig, Art Tatum and Jimmy Rowles, and saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims.” (9)

Not only did Henri Renaud supervise the above extensions of his Parisian sessions in the Big Apple, in itself an immense “first”; he also introduced his original compositions into the repertoire on the other side of the Atlantic. Burt’s Pad would be picked up by George Wallington, and Jimmy Rowles devoted a whole album to Renaud’s work.

Back in Paris, where sessions were still being set up at the last minute almost as a matter of course, Frank Foster made his first album as a leader. During a session that followed a night without sleep — it began at nine in the morning — the new “tenor hope” justified all the faith that Count Basie had put in him. Quite unexpectedly, he improvised over a French song (penned by duettists André Varel and Charly Bailly) that was known thanks to singer Jacqueline François, Escale à Victoria. It’s true that an American version also existed.

Nor was any more forward planning involved in the encounter that took place between Bob Brookmeyer, Red Mitchell and Frank Isola (actually the Gerry Mulligan Quartet minus its leader), and Jimmy Gourley and Henri Renaud, although this was a session that the latter thought disappointing. Even so, on Steeplechase, stated by Brookmeyer with a descant from Gourley, Red Mitchell and Henri Renaud himself take a fresh look at this composition by Charlie Parker.

Another specialty imported from the USA: records offering the possibility to stay at home and experience the equivalent of what a “happy few” could hear when they were packed into a basement in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. “The Third Herdsmen Blow in Paris” contained the sounds made by five members of Woody Herman’s orchestra jamming with Jean-Louis Viale and Henri Renaud on two original tunes written by Renaud: Just 40 Bars and Palm Café. There was Dick Collins, a former pupil of Darius Milhaud who’d been one of the Be Bop Minstrels in Paris at the end of the Forties; Cy Touff, one of the rare specialists on the bass trumpet; Dick Hafer and Bill Perkins, two of the best representatives of the second generation of the “Brothers”; and Red Kelly, a solid bassist who shortly afterwards went to play with the bands led by Maynard Ferguson and Stan Kenton.

Three members of the Kenton orchestra — a Dutch drummer, an American trumpeter just passing, plus a French pianist — would be among the musicians who faced each other two years later (sometime between five and eight o’clock in the morning) to play Daniel’s Blue. On one side there was Carl Fontana, one of the best modern trombones; Don Rendell, an English tenor who took after Lester Young; and Curtis Counce, an omnipresent West Coast bassist. On the other were Wes Ilcken and Dick Mills, one of Brew Moore’s old partners, who were appearing at the Caméléon club in the band led by… Henri Renaud. The effortless result in the studio was the resuscitation of the very essence of the jam session, together with all its highs, surprises and… approximations.

Some visitors prolonged their visits, and so sessions could be planned in advance more often than before; and the musicians were more than willing to play. For Roy Haynes and Joe Benjamin, Christian Chevallier composed A Mountain Sunset and Red Rose; he also wrote their arrangements, and also that of Minor Encamp, a composition whose score Duke Jordan had given to Henri Renaud. Among the partners of Sarah Vaughan’s two accompanists were the (very) young Barney Wilen and, on baritone, Jay Cameron, an Ame-rican saxophonist who’d been living in Europe for seven years; now he finally had a chance to make his first album under his own name.

To do this he called on three tenors and a rhythm section. It was an unusual line-up — a kind of tribute to the famous “Brothers” reed section — and they feature in Wooden Sword Street and Blue Note. “Jazz Magazine” hated it, but Boris Vian wrote, “Here’s an LP that has class, and its composition is original, which is definitely a pleasure.” He had the truth on his side, obviously.

Another American visitor, albeit a fleeting one, was Charles “Buzz” Gardner. Once his military service in Europe was over, he went to live in Paris for a while, during which time he showed in Thomasina that his trumpet sound was an ideal match for the guitar of René Thomas. Once back in the States he changed registers: he went to play for Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart.

In March 1956 the Olympia venue in Paris staged a programme that starred Jacqueline François, and Gerry Mulligan and his sextet opened the show. Zoot Sims was in the group and this provided the opportunity for another recording. The day before the session, after that Olympia concert, Zoot went into the studio with trumpeter Jon Eardley, who was also in Mulligan’s sextet. A few points needed clarifying with Henri Renaud’s trio and, at the musicians’ request, the tape-recorders kept spinning. This explains the origin of this recording of a free improvisation over Crazy Rhythm. Benoît Quersin replaced Eddie de Haas the following day, and the five partners made a great recording of Nuzzolese Blues while Zoot Sims kept Evening in Paris for himself. This little gem of restrained lyricism would only find its equal in 1961, with Spring Can Really Hang You Up The Most. In that same session they cut On the Alamo, which is a real lesson in swing.(10)

Zoot recorded several times in the French capital but never stayed for long, unlike his fellow musicians Allen Eager, Lucky Thompson or Sonny Criss. Allen Eager, for example, had decided to move away from music and, convinced he would make a fortune, he started work on selling the Riviera ice-cream machines on rather quickly became disillusioned, and went back to what he knew best: jazz. In the few months he spent in Paris, he was often seen duelling with Barney Wilen at the Club Saint-Germain; Eager also took part in several albums, one of the most interesting being a Franco-American octet recording with his compatriots Kenny Clarke and Billy Byers. Byers composed and arranged this Tabou Trot, a tribute to the club beneath the rue Dauphine that still preserved its aura. Henri Renaud preferred another kind of tribute and saluted his friend Zoot Sims with Mac Zooto.

Eli “Lucky” Thompson’s arrival in Europe served to catalyse multiple initiatives. For his first Parisian session he made no bones about meeting Emmett Berry in the ring, with Takin’ Care of Business — a curious major-key blues — but a fortnight later he took part in more ambitious enterprises: Meets Quincy Jones and Influence. Many years later, Mark Myers explained on his site jazzwax.com, “In 1956, the French jazz scene was bustling with local and American musicians, and a contingent of the French jazz artists were heavily influenced by the sensual, harmonic approach of Quincy Jones and Gigi Gryce, both of whom were inspired by Tadd Dameron (…) When Thompson moved to Paris in 1956, a tentet was formed almost immediately, with Renaud playing piano and arranging (…) The material is still fresh and sensational, and they are easily among my favourite Thompson recordings.” French drummer Gérard “Dave” Pochonet put together a similar line-up to support the imperial Lucky Thompson, and Easy Going allows you to hear Michel de Villers on baritone with the excellent guitarist Jean-Pierre Sasson, who also appears in One for the Boys and Us.

Sonny Criss went to Paris out of curiosity, and he stayed at a hotel on rue St Benoît; sometimes he’d come out of his hotel and bump into Marcel Romano, the artistic director of the Club Saint-Germain nearby. Romano thought he was on holiday and avoided bothering him… to the huge disappointment of Sonny. The knot finally disentangled and Sonny Criss went to play at the Chat qui Pêche club, and then went into a studio. “Henri Renaud, who was working with me, was connected with Polydor and Brunswick and he set up some sessions. We did several EP’s and one album with Philippe Combelle, Michel Gaudry, Henri, and Georges Arvanitas.” Among the titles was Don’t Blame Me.

“In the early Fifties I was fortunate to take part in numerous sessions with American musicians on their way through Paris, like Lee Konitz, Zoot Sims, Clifford Brown, Quincy Jones, Art Farmer and Roy Haynes.”(11) In the course of the decade 1952–1962, with Henri Renaud as their central pivot, American jazzmen and their French counterparts would write a full chapter in French jazz. There were other great meetings yet to come, but nothing would ever be the same again.

Adapted by Martin Davies

from the French Text of Alain Tercinet

© 2017 Frémeaux & Associés

(1) Nicolas Benies interviewing Henri Renaud (Internet source).

(2) Some discographies indicate Henri Renaud’s presence on two James Moody pieces dated 1958, You Go to My Head and Don’t Blame Me. Those performances in fact date back to 1948 or 1950. The poor sound quality prevents identifying the pianist with any certainty.

(3) Henri Renaud, “Le retour de Saturne”, Jazz Magazine N° 521, December 2001.

(4) Sleeve notes for “New Sound at the Bœuf sur le Toit”, the Fresh Sound reissue of the LP Blue Star BLP 6831.

(5) Numerous discographies give the date of this session as November 18, despite the fact that Zoot Sims and Frank Rosolino, who were still members of the Stan Kenton orchestra, were then back in the United States.

(6) “Adieu Brownie…”, Jazz Magazine N° 20, September 1956.

(7) Kurt Mohr in “À propos d’Al Cohn, une interview d’Henri Renaud”, Jazz Hot N° 104, November 1955.

(8) The three New York sessions were released as four 10” LPs on the Swing label under the titles “Henri Renaud nous rapporte des USA” and “Henri Renaud’s U.S. Stars.” Their covers were illustrated by Charles Delaunay. In later reissues the name of Henri Renaud would disappear for commercial reasons, as the names of the others were thought to be more likely to sell. Milt Jackson’s name figured conspicuously, but he was particularly irritated by this “strategy”.

(9) In the booklet from “Jimmy Rowles & Michael Moore – Profile, The Music of Henri Renaud”, Columbia.

(10) This session was specially recorded in front of an invited audience. Zoot was indeed appearing at the Blue Note with Kenny Clarke’s trio, from November 27, although his accompanists in this session are Bob Whitlock, who was then living in Paris, plus, Jean-Louis Viale and Henri Renaud. This ensemble, with Zoot, provided the music for an 18-minute short film (“Flash”) shot at the Blue Note by the underground filmmaker Allan Zion. His film retraced the wanderings of a junkie (played by Gary Goodrow) who had portrayed one of the characters in “The Connection” both onstage and onscreen. “Flash”, which had trouble with the censors, seems to have vanished.

(11) Matthieu Jouan, “Henri Renaud – Le jubilé du jazz”, Citizen Jazz.

« Saint-Germain réussissait autour de la musique ce que Montparnasse avait fait autour de la peinture après 1918. Et pas n’importe quelle musique : le jazz. » Henri Renaud

“Saint-Germain achieved as much for music as Mont‑parnasse had for painting after 1918. And not just any music: jazz.” Henri Renaud

CD 1

HENRI RENAUD ALL-STARS

1. VENEZ DONC CHEZ MOI 4’37

HENRI RENAUD ALL-STARS

2. MAHOGANY HALL STOMP 3’25

LEE KONITZ QUARTET

3. RECORD SHOP SUEY 3’21

4. 4 : 00 P. M. 2’46

ZOOT SIMS SEXTET

5. TOOT’S SUITE 5’53

6. THE LATE TINY KAHN 4’28

HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

7. SCHABOZZ 3’12

GIGI GRYCE AND HIS BAND

8. KEEPING UP WITH JONESY 7’11

CLIFFORD BROWN SEXTET

9. I COVER THE WATERFRONT 4’04

CLIFFORD BROWN / GIGI GRYCE SEXTET

10. BABY 5’44

11. STRICTLY ROMANTIC 4’16

ART FARMER NEW STARS JAZZ

12. SERENADE TO SONNY 2’39

CLIFFORD BROWN QUARTET

13. IT MIGHT AS WELL BE SPRING 5’01

HENRI RENAUD / AL COHN QUARTET

14. LAZY THINGS 4’27

15. NY’S IDEA – 1 2’15

16. NY’S IDEA – 2 3’18

HENRI RENAUD BAND

17. WALLINGTON SPECIAL 6’01

CD 2

HENRI RENAUD ALL-STARS

1. I’LL REMEMBER APRIL 8’53

OSCAR PETTIFORD ALL-STARS

2. BURT’S PAD 9’44

3. MARCEL THE FURRIER 5’58

4. E-LAG 2’33

FRANK FOSTER QUARTET

5. ESCALE A VICTORIA 4’42

THE HERDSMEN

6. JUST 40 BARS 4’16

7. PALM CAFE 5’46

RENÉ THOMAS ET SON QUINTETTE

8. THOMASIA 4’23

BOB BROOKMEYER QUINTET

9. STEEPLECHASE 6’42

ROY HAYNES BAND

10. A MOUNTAIN SUNSET 4’33

11. RED ROSE 3’50

12. MINOR ENCAMP 5’07

JAY CAMERON’S INTERNATIONAL SAX BAND

13. BLUE NOTE 3’10

14. WOODEN SWORD STREET 3’29

CD 3

LUCKY THOMPSON QUINTET

1. TAKIN’ CARE OF BUSINESS 4’22

MODERN JAZZ GROUP feat. LUCKY THOMPSON

2. MEET QUINCY JONES 3’46

3. INFLUENCE 4’02

ZOOT SIMS / HENRI RENAUD QUINTET

4. CRAZY RHYTHM 7’55

5. NUZZOLESE BLUES 7’26

6. EVENING IN PARIS 3’23

THE KENTONIANS

7. DANIEL’S BLUES 11’50

LUCKY THOMPSON & DAVE POCHONET ALL-STARS

8. EASY GOING 4’11

9. ONE FOR THE BOYS AND US 7’17

HENRI RENAUD OCTETTE

10. MAC ZOOTO 4’06

11. THE TABOU TROT 3’46

SONNY CRISS QUARTET

12. DON’T BLAME ME 2’48

ZOOT SIMS QUARTET

13. SPRING CAN REALLY HANG YOU UP THE MOST 3’09

14. ON THE ALAMO 5’41