- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

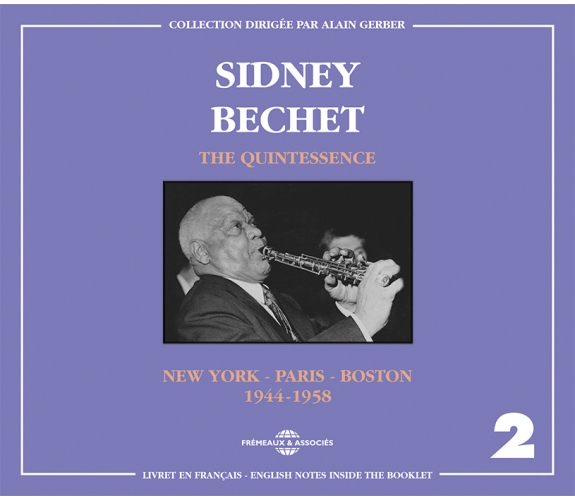

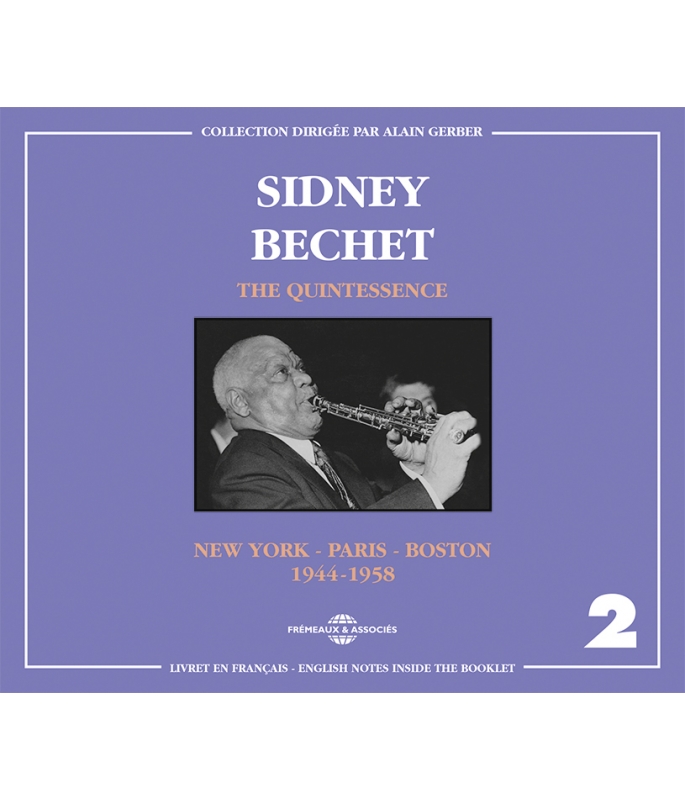

NEW YORK - PARIS - BOSTON, 1944-1958

SIDNEY BECHET

Ref.: FA3071

EAN : 3448960307123

Artistic Direction : ALAIN GERBER AVEC DANIEL NEVERS ET ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 25 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

NEW YORK - PARIS - BOSTON, 1944-1958

NEW YORK - PARIS - BOSTON, 1944-1958

“He’s mad about his art, this man; you can see that, for him, music is one of his vital functions. How we’d love all musicians to be like him!” Alfred LOEWENGUTH (violinist known for his prestigious performances of Ravel and Debussy, among others)

Frémeaux & Associés’ « Quintessence » products have undergone an analogical and digital restoration process which is recognized throughout the world. Each 2 CD set edition includes liner notes in English as well as a guarantee. This 2 CD set presents a selection of the best recordings by Sidney Bechet between 1944 and 1958.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blue HorizonSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:04:281944

-

2High SocietySidney BechetP. Steele00:03:371945

-

3Weary BluesSidney BechetA. Matthews00:04:211945

-

4Days Beyond RecallSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:04:511945

-

5Up In Sidney's FlatSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:04:231945

-

6Bowin' The BluesSidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:02:471945

-

7Gone Away BluesSidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:02:431945

-

8Out Of The GallionSidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:02:311945

-

9Save It Pretty MamaSidney BechetP. Steele00:03:101945

-

10Old Stack O Lee BluesSidney BechetP. Steele00:04:141946

-

11China BoySidney BechetP. Steele00:03:591946

-

12LauraSidney BechetD. Raskin00:03:091947

-

13Really The Blues – Part ISidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:03:091947

-

14Really The Blues – Part IISidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:02:561947

-

15Chicago Function – Part ISidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:04:111947

-

16Chicago Function – Part IISidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:03:421947

-

17I'M Speaking My MindSidney BechetMezz Mezzrow00:04:091947

-

18Love Me With A FeelingSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:181949

-

19Bechet's Creole BluesSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:101949

-

20Ce mossieu qui parleSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:381949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Buddy Bolden StorySidney BechetTraditionnel00:03:381949

-

2Moulin à caféSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:02:571950

-

3En attendant le jourSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:251951

-

4Original Dixieland One StepSidney BechetD.J. Larocca00:04:171951

-

5Si tu vois ma mèreSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:161952

-

6Petite fleurSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:111952

-

7Big Butter And Egg ManSidney BechetP.F. Venable00:03:001952

-

8Limehouse BluesSidney BechetP.F. Venable00:03:241952

-

9Black And BlueSidney BechetA. Razaf00:03:361953

-

10Honeysuckle RoseSidney BechetA. Razaf00:06:521953

-

11TemperamentalSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:03:221954

-

12Tin Roof BluesSidney BechetMares00:08:421956

-

13Passport To ParadiseSidney BechetSidney Bechet00:02:571956

-

14The Man I LoveSidney BechetG And I Gerschwin00:02:441957

-

15All The Things You AreSidney BechetJ. Kern00:02:451957

-

16I Don'T Mean A ThingSidney BechetD. Ellington00:02:581957

-

17Amour perduSidney BechetR. Bagdasarian00:03:221957

-

18I Can'T Get StartedSidney BechetV. Duke00:04:451958

-

19Les OignonsSidney BechetV. Duke00:04:221958

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOKLET

Bechet vol.2

COLLECTION DIRIGÉE PAR ALAIN GERBER

SIDNEY

BECHET

NEW YORK - PARIS - BOSTON

1944-1958

THE QUINTESSENCE

Volume 2

LIVRET EN FRANÇAIS - ENGLISH NOTES INSIDE THE BOOKLET

SIDNEY BECHET -– volume 2

DISCOGRAPHIE / DISCOGRAPHY

CD 1 (1944-1949)

1. BLUE HORIZON (S.Bechet) (Blue Note 43 / mx. BN 208) 4’28

SIDNEY BECHET’S BLUE NOTE JAZZMEN

Sidney De PARIS (tp) ; Vic DICKENSON (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, ss) ; Art HODES (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Manzie JOHNSON (dm). New York City, 20/12/1944

2. HIGH SOCIETY (P.Steele) (Blue Note 50 / mx. BN 215-1) 3’37

3. WEARY BLUES (A.Matthews) (Blue Note 49 / mx. BN 217-1) 4’21

SIDNEY BECHET’S BLUE NOTE JAZZMEN

Max KAMINSKY (tp) ; George LUGG (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, ss) ; Art HODES (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Freddie MOORE (dm). New York City, 29/01/1945

4. DAYS BEYOND RECALL (S.Bechet) (Blue Note 564 / mx. BN 226) 4’51

5. UP IN SIDNEY’S FLAT (S.Bechet) (Blue Note 565 / mx. BN 228-1) 4’23

BUNK JOHNSON & SIDNEY BECHET’S BAND

Willie “Bunk” JOHNSON (tp) ; Sandy WILLIAMS (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (cl) ; Cliff JACKSON (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Manzie JOHNSON (dm). New York City, 10/03/1945

6. BOWIN’ THE BLUES (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-141 / mx. KJ 26-2) 2’47

7. GONE AWAY BLUES (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-140 / mx. KJ 30-1) 2’43

8. OUT OF THE GALLION (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-142 / mx. KJ 32-3) 2’31

MEZZROW-BECHET QUINTET

Milton “Mezz” MEZZROW (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Fitz WESTON (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Joseph “Kaiser” MARSHALL (dm). New York City, 29 & 30/08/1945

9. SAVE IT, PRETTY MAMA (Don Redman) (Blue Note 531 / mx. BN 262-1) 3’10

ART HODES’ HOT FIVE

Wild Bill DAVISON (cnt) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, ss) ; Art HODES (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Freddie MOORE (dm). New York City, 12/10/1945

10. OLD STACK O’ LEE BLUES (S.Bechet) (Blue Note 54 / mx. BN 277-1) 4’14

BECHET-NICHOLAS BLUE FIVE

Albert NICHOLAS (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, ss) ; Art HODES (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Danny ALVIN (dm). New York City, 12/02/1946

11. CHINA BOY (Winfree-Boutelje) (Folkways FJ-2841) 3’59

JAZZ AT TOWN HALL (123 W. 43rd Street)

Sidney BECHET (ss) ; James P. JOHNSON (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Warren “Baby” DODDS (dm). New York City (Town Hall), 21/09/1946

12. LAURA (D.Raksin-J.Mercer) (Columbia 38318 / mx. Co 38042-1) 3’09

SIDNEY BECHET QUARTET

Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Lloyd PHILLIPS (p) ; George “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Arthur HERBERT (dm). New York City, 31/07/1947

13. REALLY THE BLUES – Part I (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-146 /mx. KJ 34-2) 3’09

14. REALLY THE BLUES – Part II (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-146 /mx. KJ 35-) 2’56

MEZZROW-BECHET QUINTET

M. “Mezz” MEZZROW (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss, cl) ; Socks WILSON (p) ;Wellman BRAUD (b) ; W. “Baby” DODDS (dm). New York City, 18/09/1947

15. CHICAGO FUNCTION – Part I (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-5 /mx. KJ 45-2) 4’11

16. CHICAGO FUNCTION – Part II (M.Mezzrow) (King Jazz K-5 /mx. KJ 46-2) 3’42

17. I’M SPEAKING MY MIND (Mezzrow-Bechet) (King Jazz K-8 /mx. KJ 48-3) 4’09

MEZZROW-BECHET QUINTET

M. “Mezz” MEZZROW (cl) ; Sammy PRICE (p) ; G. “Pops’ FOSTER (b) ; J. “Kaiser” MARSHALL (dm). New York City, 19 & 20/12/1947

18. LOVE ME WITH A FEELING (S.Bechet) (Circle J 1059 / mx. NY 94-B) 3’18

SIDNEY BECHET with BOB WILBER AND HIS JAZZ BAND

Henry GOODWIN (tp) ; James ARCHEY (tb) ; Bob WILBER (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (cl, ss, voc) ; Dick WELLSTOOD (p) ; G. “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Tommy BENFORD (dm). New York City, 8/06/1949

19. BECHET’S CREOLE BLUES (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5014 / mx. V 3017) 3’10

20. CE MOSSIEU QUI PARLÉ (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5013 / mx. V 3015) 3’38

SIDNEY BECHET avec CLAUDE LUTER et Son Orchestre

Pierre DERVAUX (cnt) ; Claude PHILIPPE (tp, bj) ; Claude LUTER (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Christian AZZI (p) ; Roland BIANCHINI (b) ; François “Moustache” GALÉPIDÈS (dm). Paris, 14/10/1949

CD 2 (1949-1958)

1. BUDDY BOLDEN STORY (Trad.) (Vogue 5013 / mx. V 3016) 3’38

SIDNEY BECHET avec CLAUDE LUTER et Son Orchestre

Comme pour 19 & 20 CD 1 / As for 19 & 20 CD 1. Luter & Bechet dialoguent / Claude & Sidney talking. Paris, 14/10/1949

2. MOULIN À CAFÉ (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5066 / mx. V3095-2) 2’57

SIDNEY BECHET avec CLAUDE LUTER et Son Orchestre

Pierre DERVAUX (tp) ; Bernard ZACHARIAS (tb) ; Claude LUTER (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Christian AZZI (p) ; Roland BIANCHINI (b) ; François “Moustache” GALÉPIDÈS (dm). Paris, 6/10/1950

3. EN ATTENDANT LE JOUR (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5093 / mx. V 4049-1) 3’25

SIDNEY BECHET avec CLAUDE LUTER et Son Orchestre

Formation comme pour 2 / Personnel as for 2. Guy LONGNON (vtb) remplace/replaces ZACHARIAS. Paris, 4/05/1951

4. ORIGINAL DIXIELAND ONE-STEP (D.J.LaRocca) (Blue Note BLP 1207 / mx. BN 416-3) 4’17

SIDNEY BECHET AND HIS HOT SIX

Sidney De PARIS (tp) ; James ARCHEY (tb) ; Don KIRKPATRICK (p) ; G. “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Manzie JOHNSON (dm). New York City, 5/11/1951

5. SI TU VOIS MA MÈRE (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5076 / mx. V 4202-1) 3’16

SIDNEY BECHET avec CLAUDE LUTER et Son Orchestre

Guy LONGNON (tp) ; Bernard ZACHARIAS (tb) ; Claude LUTER (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Christian AZZI (p) ; Claude PHILIPPE (bj) ; Roland BIANCHINI (b) ; F. “Moustache” GALÉPIDÈS (dm). Paris, 18/01/1952

6. PETITE FLEUR (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5119 / mx. V 4176) 3’11

SIDNEY BECHET ALL STARS

Guy LONGNON (tp) ; Jean-Louis DURAND (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Charlie LEWIS (p) ; Alf MASSELIER (b) ; Armand MOLINETTI (dm). Paris, 21/01/1952

7. BIG BUTTER AND EGG MAN (P.F.Venable) (Vogue LD 094 / mx. V 4327) 3’00

8. LIMEHOUSE BLUES (D.Furber-P.Braham) (Vogue 5138 / mx. V 4326) 3’24

SIDNEY BECHET TRIO

Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Lil HARDIN-ARMSTRONG (p, voc) ; Zutty SINGLETON (dm). Paris, 7/10/1952

9. BLACK AND BLUE (T.Waller-A.Razaf) (Blue Note BLP 1207/mx.BN 519-1) 3’36

SIDNEY BECHET BLUE NOTE JAZZMEN

Jonah JONES (tp) ; James ARCHEY (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Buddy WEED (p) ; Walter PAGE (b) ; Johnny BLOWERS (dm). New York City, 25/08/1953

10. HONEYSUCKLE ROSE (T.Waller-A.Razaf) (Storyville LP 902) 6’52

JAZZ AT STORYVILLE

Vic DICKENSON (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; George WEIN (p) ; Jimmy WOODE (b) ; Buzzy DROOTIN (dm). Boston (Ma), Storyville Club, 25/10/1953

11. TEMPERAMENTAL (S.Bechet) (Vogue 5190 / mx. V 4797-1) 3’22

SIDNEY BECHET avec ANDRÉ RÉWÉLIOTTY et Son Orchestre

Marcel BORNSTEIN, Guy LONGNON (tp) ; Jean-Louis DURAND (tb) ; André RÉWÉLIOTTY (cl) . Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Yannick SINGÉRY (p) ; Georges “Zozo” D’HALLUIN (b) ; Michel PACOUT (dm). Paris, 11/03/1954

12. TIN ROOF BLUES (Mares-Brunies-Roppolo-Schoebel) (Vogue-Swing LDM 30041 / mx. V 5857) 8’42

SIDNEY BECHET with SAMMY PRICE’S BLUESICIANS

Emmett BERRY (tp) ; George STEVENSON (tb) ; Herbert HALL (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Sammy PRICE (p) ; G. “Pops” FOSTER (b) ; Freddie MOORE (dm). Paris, 16/05/1956

13. PASSPORT TO PARADISE (S.Bechet) (Vogue EPL 76605 / mx. V 6022-1) 2’57

SIDNEY BECHET avec ANDRÉ RÉWÉLIOTTY et Son Orchestre

Guy LONGNON (tp) ; Jean-Louis DURAND (tb) ; André RÉWÉLIOTTY (cl) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Eddie BERNARD (p) ; G. “Zozo” D’HALLUIN (b) ; Jacques DAVID (dm). Paris, 26/06/1956

14. THE MAN I LOVE (G.&I.Gershwin) (Vogue-Swing LDM 30065) 2’44

SIDNEY BECHET – MARTIAL SOLAL QUARTET

Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Martial SOLAL (p) ; Lloyd THOMPSON (b) ; Al LEVITT (dm). Paris, 12/03/1957

15. ALL THE THINGS YOU ARE (J.Kern) (Vogue-Swing LDM 30065) 2’45

16. IT DON’T MEAN A THING (E.K.Ellington) (Vogue-Swing LDM 30065) 2’58

SIDNEY BECHET – MARTIAL SOLAL QUARTET

Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Martial SOLAL (p) ; Pierre MICHELOT (b) ; Kenny CLARKE (dm). Paris, 17/06/1957

17. AMOUR PERDU (R.Bagdasarian-R.Rouzeau) (Vogue EPL 7359 /mx.V 6624) 3’22

SIDNEY BECHET avec ANDRÉ RÉWÉLIOTTY et Son Orchestre

Formation comme pour 13 / Personnel as for 13. Marcel BLANCHE (dm) remplace/replaces J. DAVID. Paris, 26/06/1957

18. I CAN’T GET STARTED (V.Duke-I.Gershwin) (Vogue-Swing LDM 30092) 4’45

SIDNEY BECHET & TEDDY BUCKNER

Teddy BUCKNER (tp) ; Christian GUÉRIN (tb) ; Sidney BECHET (ss) ; Eddie BERNARD (p) ; Roland BIANCHINI (b) ; Kansas FIELDS (dm). Paris, 4/07/1958

19. LES OIGNONS (S.Bechet) (Vogue CSB 2) 4’22

SIDNEY BECHET QUINTET

Claude GOUSSET (tb, arr) ; Sidney BECHET (présentation, ss) ; Jean-Claude PELLETIER (orgue) ; Alix BRET (b) ; Kansas FIELDS (dm). Paris, 12/12/1958 (la dernière séance / the last session)

LE CHAPERON QU’ON N’ESPÉRAIT PLUS

De propos délibéré, nous n’avons pas voulu exclure de la seconde anthologie consacrée à Sidney Bechet des pièces incontestablement mineures dans l’ordre esthétique, surtout si on les compare à la sélection inaugurale, Blue Horizon, non seulement un chef-d’œuvre de son signataire, mais encore un joyau du jazz enregistré dans son ensemble. En attendant le jour, Si tu vois ma mère, Petite fleur, Passeport To Paradise et Les Oignons (ici dans une version peu orthodoxe) figurent au programme de ce coffret à un double titre. D’une part, ces mélodies imaginées par un citoyen des États-Unis appartiennent de plein droit à notre patrimoine culturel national, indissociables qu’elles sont de notre mémoire collective, au même titre que les chansons de Charles Trenet pour ne prendre que cet exemple. D’autre part, elles résument par leur existence une histoire longue et complexe, en même temps qu’elles illustrent un phénomène, social tout autant qu’artistique, plein d’enseignement. C’est ce qu’on souhaiterait montrer maintenant.

La Nouvelle-Orléans, « berceau du jazz » ? Voilà une idée reçue qui ne l’a pas été par tout le monde et qu’il conviendrait sans doute, à tout le moins, de nuancer. Il n’en reste pas moins qu’un certificat de baptême sur lequel ne figurerait pas le nom de la ville aurait toutes les raisons de passer pour un faux. Et même, l’officier de l’état civil serait avisé d’insister sur ce nom en écrivant « Les », plutôt que « La » Nouvelle-Orléans. Car ce furent des quartiers distincts, disjoints, dissemblables, voire antagonistes qui, chacun à sa façon, participèrent à l’élaboration du brouet de sorcière dans le melting-pot louisianais, carrefour de mondes, de dieux, de langues, d’usages, de rêves debout et de rêves brisés, de communautés et de solitudes.

La vulgate, en matière d’histoire du jazz, imposa longtemps de considérer cette musique comme une production exclusivement noire. Au point que si l’observateur tombait nez à nez avec un instrumentiste blanc — et, pour son malheur, il y en eut de nombreux dès le début du siècle, autour de catalyseurs comme le joueur de grosse caisse « Papa » Jack Laine ou le trombone Tom Brown — il s’empressait de faire de ce gêneur un intrus en expliquant soit qu’il était nécessairement médiocre et de ce fait quantité négligeable, soit qu’il se bornait à copier (singer, piller, les variantes sémantique sont nombreuses) les seuls créateurs dignes de ce nom, originaires de l’Afrique, soit encore que son jazz, si attrayant pût-il paraître, n’était pas le vrai. Le vrai étant par définition « de couleur », il n’était pas trop difficile de le désigner. D’aucuns s’en firent une spécialité : ces fins connaisseurs n’avaient pas leur pareil pour repérer une boule de neige dans un tas de charbon.

L’immigration italienne, dans la Cité du Croissant, n’avait rien d’un phénomène anecdotique. Ainsi les Siciliens s’entassaient-ils dans le French Quarter (« Vieux Carré », terre de désolation bien avant de devenir piège à touristes), habité par des Noirs à l’encontre desquels, selon George E. Cunningham (1), ils n’entretenaient pas de préjugés raciaux et avec lesquels ils étaient d’ailleurs souvent confondus, jusqu’à se faire interdire l’accès aux écoles pour Blancs dans les localités voisines et même, en une occasion au moins, à subir la loi de Lynch. Ces gens, selon une habitude bien ancrée, importèrent le crime organisé, en échange de quoi nombre d’entre eux furent « suffisamment conquis par le jazz pour en jouer eux-mêmes » (2). Pour mesurer l’importance de la contribution péninsulaire à l’émergence d’un art neuf, il suffira d’évoquer le souvenir de vétérans comme le cornettiste Nick La Rocca, leader de l’Original Dixieland Jass Band qui signa en 1917 le tout premier enregistrement de jazz, comme le clarinettiste Leon Roppolo, essentiel au succès des New Orleans Rhythm Kings, ou comme le batteur Tony Sbarbaro, membre de l’ODJB lui aussi. À New York et à Chicago, un peu plus tard, la diaspora juive d’Europe centrale interviendrait à son tour dans le processus (3). Les uns et les autres, note l’historien Jude Teller, éprouvaient d’ailleurs « une sorte de sympathie » réciproque.

Mais ce n’est pas tout. Ceux que l’on avait tendance à regarder de ce côté-ci de l’Atlantique comme « les Noirs de La Nouvelle-Orléans » formaient en réalité, sur place, deux groupes qui n’entendaient pas qu’on les confondît et auxquels, une législation en vigueur jusqu’en 1894, n’accordait d’ailleurs, pas le même statut, bien qu’il fût (et demeure) difficile de tracer entre eux une frontière lisible : d’un côté, les « purs » Noirs, estampillés comme tels en dépit de leurs divers degrés de métissage ; de l’autre, les sang-mêlé officiellement reconnus, ceux que l’on appelait là-bas, dans une acception du mot différente de celle qui prévaut aux Antilles, les « Créoles ». Le dentiste Leonard Bechet, frère aîné de Sidney, rappellera que les hommes à peau sombre qui opéraient uptown « buvaient beaucoup » et « jouaient de la musique vulgaire », tandis que downtown, les mulâtres, éduqués, bons lecteurs de partitions, instrumentistes disciplinés, interprètes déférents, s’efforçaient d’avoir de la tenue, à la scène comme à la ville. Et de préciser que lorsque les seconds découvrirent ce que les premiers tiraient de leurs instruments, ils jugèrent que cette chose-là « contenait toute la brutalité nègre ». Les Créoles, eux, étaient nourris d’une tradition musicale qui remontait au temps où la Louisiane, avant que Napoléon 1er ne la vendît aux Etats-Unis, était encore, pour de bon, l’une des colonies du roi Louis (XV). À distance, cette tradition s’était plus ou moins réglée au fil du temps sur les modes européennes successives. Ses représentants avaient excellé dans le quadrille et la polka, la mazurka et la marche ; le ragtime leur convenait à merveille. Autant dire que, lorsqu’ils s’essaieraient au jazz à leur tour, spontanément ils ajouteraient à la formule, où se remarquait déjà une touche hispanique (elle inspire par exemple le rythme de habanera de Saint Louis Blues) un peu de l’influence française dont ils s’enorgueillissaient. Les noms de famille qu’ils portaient, au reste, étaient souvent français — à commencer par celui des Bechet, auquel Lucien Malson proposa de restituer son accent aigu originel : Béchet. Baquet, Piron, Picou, Robicheaux, Pavageau — on n’en finirait plus de réciter l’annuaire.

Avant l’adolescence déjà, s’il faut en croire son frère, Sidney a remarqué que les musiciens de la même origine que lui, lorsqu’ils « répugnent à se frotter aux gens de bas-étage (…) ne vont jamais très loin. » Car « il faut jouer très dur quand on joue pour les Noirs (…) Il faut se hisser à leur niveau (…) Ces musiciens hot, ils se tuent à jouer, comprenez-vous ? » L’enfant, justement, l’a fort bien compris et ne désire rien d’autre que de souffler à mort. En disciple déclaré de Louis « Big Eye » Nelson, clarinettiste de braise et de fièvre, brûleur de nuit sans sommeil, il noircit sa manière autant qu’il en est capable. D’un même élan, toutefois, il déverse dans cette sauvagerie paradoxale, car recherchée et entretenue avec méthode, toute la suavité, l’urbanité, le charme, la tendresse, toute la douce mélancolie créole aussi que les siens ont reçus en héritage. De la sensualité à l’état naturel et de la sensualité comme degré supérieur de civilisation il fait en conjuguant la violence de l’une au raffinement de l’autre un seul mode d’expression, qui est celui d’un lyrisme aussi insinuant qu’irrépressible : agresser et séduire, inquiéter et enchanter, suggérer et mettre à nu deviennent avec lui strictement synonymes.

Dans sa ville natale, il s’était rapproché des Noirs, non sans faire scandale dans un milieu avide de respectabilité (4) et, semble-t-il, non sans se féliciter in petto de cette réaction. À Paris, une cinquantaine d’années plus tard, il se tourne de l’autre côté, s’exprimant dans la langue du pays qui l’adopte (cf. ici Buddy Bolden Story), exhibant et exploitant sa créolité (5) dans le but manifeste de flatter le sentiment national de son nouveau public et, partant, d’asseoir la bonne réputation dont il bénéficie dans toutes les couches de la société, plus largement qu’aucun autre jazzman mort ou vivant. Plus largement que Louis Armstrong, sans aucun doute. Peut-être même plus largement que Django Reinhardt, lequel n’est plus alors tout à fait la légende vivante qu’il avait été pendant l’Occupation. Grâce à Sidney, la France, enfin, se découvre partie prenante dans la genèse de la musique afro-américaine. Nos compatriotes ne se sentent plus aussi étrangers qu’ils l’imaginaient à ce qui avaient été pour eux, d’abord « une musique de nègres », avec ce que cela supposait d’exotisme brouillon mais bon enfant, puis, en dépit des brevets accordés par Jean Cocteau, Erik Satie, Darius Milhaud (relayés plus tard par Julio Cortazar, Georges Auric, Michel Leiris, Jean-Paul Sartre, et quelques autres) « une musique de sauvages » : celle des zazous de l’anti-France, sous Pétain, avant d’être celle, mieux acceptée, des GI’s à la Libération.

Sans contestation possible, Sidney est à la surface de la Terre le plus français des jazzmen. Django et quelques autres avaient avant lui improvisé sur des chansons populaires de fabrication locale (Vous qui passez sans me voir, par exemple, ou Clopin-clopant) — mais toujours par exception. Bechet, qui célèbre le 14 juillet (6) à la bonne franquette, inscrit allègrement à son répertoire Au clair de la lune, Ce n’est que votre main, Madame, La complainte des infidèles, des airs de Vincent Scotto (J’ai deux amours), Joseph Kosma (Bonjour Paris), Maurice Yvain (J’en ai marre), Henri Salvador (Le loup, la biche et le chevalier) ou George Brassens (Brave Margot, La Cane de Jeanne, Le Fossoyeur). Les titres de ses propres compositions, bien souvent, fleurent bon le cher pays de notre enfance : Moustache gauloise, Pattes de mouche, Dans les rues d’Antibes, Promenade aux Champs-Élysées, À moi d’payer, Pas d’blague, Bagatelle, Bravo !, Aubergines, poivrons et sauce tomate, Premier bal…

Bien évidemment, il n’est pas ce qu’on appelle à Montréal « un Français de France », mais d’une certaine façon, il est mieux que cela. Dans les profondeurs du subconscient, il apparaît comme le rescapé d’une vieille France aux mœurs exquises, idéalement douce à vivre, qui sans doute n’avait jamais existé et surtout pas en Louisiane négrière, mais dont les Français d’alors n’éprouvaient pas moins le sentiment d’avoir été dépossédés. Par la défaite de 1870 d’abord, par l’hécatombe de la Grande guerre ensuite et enfin par la barbarie réglée du conflit mondial dont ils venaient à peine de sortir. Le paradis perdu a bel et bien existé : Sidney Bechet, qu’on peut voir et toucher, en arrive tout droit et témoigne avec son instrument de splendeurs et de fêtes disparues. Prolongeant l’oncle Tom, préfaçant l’uncle Ben, il incarne en outre l’idée, pittoresque et attendrissante mais complètement à côté de la plaque, que le métropolitain se fait — et se fera longtemps encore — de l’Antillais. Bref, il est le Doudou paradigmatique des Français. On va voir qu’en un certain sens, il est aussi leur doudou, l’« objet transitionnel » grâce à quoi, en pleine guerre froide, ils comptent passer sans y laisser trop de plumes d’un univers protecteur dont ils n’ont pas assez profité à un monde hostile qu’ils ne connaissent déjà que trop. Cette scène effrayante où ils doivent tant bien que mal tenir leur rôle devient avec lui un théâtre sans cruauté.

La rage et les menaces ne sont pas absentes de sa musique, trop flamboyante pour en faire l’économie, mais elles ne sont plus, dans ce contexte, que les lois d’un genre, les éléments d’un style. Comme dans le carnaval, la flagrante suspension des codes s’y trouve elle-même codifiée avec précision. On sait par avance jusqu’où ira la licence ; on a la garantie qu’elle prendra fin ; on est averti par toutes les autorités en place du jour et de l’heure où le signal en sera donné. Quelques fauteuils brisés à l’Olympia, en 1954, ne représentent pas un si lourd tribut à verser pour qu’en définitive l’ordre l’emporte. Justement parce qu’il n’est pas que sentimental, Bechet rassure : il est la vivante démonstration que la violence peut ne pas être mortelle, ni même très dommageable à y bien regarder.

Du coup, on va entendre le jazz, en tout cas ce jazz-là, d’une façon différente. C’est une musique-de-jeunes, certes, mais comme on l’a confiée à un gentil vieux bonhomme conscient de ses responsabilité, il n’y a pas à s’en faire. Sidney est le chaperon que l’on n’espérait plus, un soulagement pour les parents d’élèves et les sergents de ville. Il contrôle les débordements d’autant mieux qu’il en est l’ordonnateur. Il les provoque à loisir — il y met fin à volonté, en raison du respect qu’on porte aux cheveux blancs. Voilà que l’amour du jazz — l’amour qu’on lui porte, mais aussi, plus précieux encore, l’amour qu’on reçoit de lui — n’est plus réservé à une poignée d’excentriques et de marginaux. Les snobs, les pédants et les intellectuels dévoyés n’accèdent plus seuls à sa compréhension. Sa jouissance, aux deux sens du mot, tout à coup est ouverte à tous. On peut ne pas sortir de Polytechnique, ne pas fréquenter les caves enfumées au bras d’une fille qui fait semblant de lire L’Être et le Néant, et cependant savourer Les Oignons.

Sidney meurt à Garches le 14 mai 1959, emporté par un cancer. À cette date, Pour ceux qui aiment le jazz triomphe à la radio, Art Blakey et ses Jazz Messengers jouissent encore d’une certaine popularité dans le pays. Cette manière d’âge d’or sera de courte durée. Bientôt, la musique afro-américaine y redeviendra ce qu’elle était auparavant, ce qu’elle reste aujourd’hui en dépit d’une tolérance affichée : une indésirable. Il est vrai que le désir, si indomptable chez l’individu, incline au sein de la société à faire où on lui dit de faire.

Alain Gerber

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

(1) In Journal of Negro History.

(2) Ronald L. Morris in Le jazz et les gangsters.

(3) Dans The Dearborn Independent, journal subventionné par le constructeur automobile Henry Ford, on pourra lire ceci, en 1921 : « Le jazz est une création juive. Cette bouillie, cette fange, ces suggestions sournoises, la lubricité avilissante de ces notes qui dégoulinent sont d’essence juive. »

(4) Leonard Bechet encore une fois : « Nous autres, musiciens créoles,… nous exigions le respect parce que nous faisions de la bonne musique. » (Entendez : de la musique tirée au cordeau.)

(5) Lucien Malson : « Cé Mossieu qui parlé, Béchet Creole Blues, Les Oignons… se rattachent à la tradition de La Nouvelle-Orléans métisse » (Les maîtres du jazz).

(6) Enregistrement en date du 26 février 1957.

SIDNEY BECHET Volume 2 – À PROPOS DE LA PRÉSENTE SÉLECTION

Lorsque le 20 décembre 1944 Sidney Bechet franchit à New York les portes des studios WOR, plus de deux ans se sont écoulés depuis l’enregistrement du Blues in the Air qui terminait le volume précédent. Entre-temps, une seule séance officielle et trois faces pour les V-Discs… James Cæsar Petrillo, président de l’American Federation of Musicians, avait décrété une grève de l’enregistrement commencée en août 1942 et terminée en novembre 1944.

RCA Victor en ayant profité pour dénoncer son contrat, Bechet s’était retourné vers Alfred Lion pour lequel il avait déjà travaillé. Adieu les « New Orleans Feetwarmers » au sein desquels aucun trompettiste n’avait remplacé de façon permanente Tommy Ladnier, bonjour les « Blue Note Jazzmen ». Un ensemble similaire au précédent qui démarra sous les meilleurs auspices : avec Blue Horizon – une composition originale dont il était le seul soliste à la clarinette - , Bechet signait l’une de ses plus belles interprétations sur tempo lent.

Un mois plus tard, il s’attaque à High Society, reprenant avec maestria le fameux solo d’Alphonse Picou, tout en inventant variations et contrechants derrière Max Kaminsky, un trompettiste rencontré au cours des Eddie Condon’s Floor Shows qui, visiblement, l’inspire. Au soprano - un instrument plus dominant que la clarinette - , Bechet choisit pourtant, sur Weary Blues, de se fondre dans les ensembles. Une approche qu’il ne cultivera plus guère.

En ouverture de Buddy Bolden Blues, Sidney raconta à Claude Luter qu’en 1910, Bunk Johnson venait le chercher chez ses parents pour l’emmener jouer de la clarinette au sein de l’Eagle Band ; à ses dires il avait alors… douze ans.

Dès 1934, à la suite de divers ennuis de santé, Bunk Johnson avait pratiquement abandonné la musique. Quatre ans plus tard, au cours des recherches pour leur livre « Jazzmen », Bill Russell et Frederic Ramsey le retrouvèrent en Louisiane, à New Iberia. Conducteur de tracteur dans les rizières, il gagnait 1.50 $ par jour. En 1942, pourvu d’un nouvel appareil dentaire et d’une trompette neuve, considéré comme le dernier représentant du jazz pur et dur des origines, Bunk Johnson enregistrait pour la première fois. Il rejoindra ensuite, à San Francisco, le Lu Watter’s Yerba Buena Jazz Band à l’origine du « New Orleans Revival » sur la côte ouest.

De passage à la Nouvelle-Orléans, Bechet entendit Bunk au cours d’un concert. L’Eagle Band lui ayant laissé de bons souvenirs, il proposa au trompettiste de l’accompagner à New York. Projetant de s’y rendre à la tête de son propre orchestre, Bunk Johnson trouvait là une opportunité pour se faire un peu mieux connaître.

Les deux nouveaux partenaires se produisirent le 10 mars au Jimmy Ryan’s Club à l’initiative de Milt Gabler. Ce fut pourtant Alfred Lion qui, le même soir, les enregistra, Cliff Jackson et Manzie Johnson remplaçant Hank Duncan et Kaiser Marshall au piano et à la batterie. La musique était interprétée telle que Bunk Johnson entendait qu’elle le soit, avec son lot d’improvisations collectives. Bechet avait souscrit à ce projet et, pas plus au long de Days Beyond Recall que sur Up in Sidney’s Flat, deux de ses compositions, il ne tentera de tirer la couverture à lui. Que ses solos surpassent ceux de son interlocuteur est une autre histoire.

Au cours d’un long engagement au Savoy Café de Boston, leur association se délita. Le goût prononcé pour le whisky manifesté par le trompettiste le mettait souvent dans l’incapacité de jouer, ce qui exaspérait Bechet, pourtant étranger à toute ligue de tempérance. Remplaceront Bunk Johnson, Johnny Windhurst, âgé seulement de 18 ans, rencontré par Bechet chez Eddie Condon puis Peter Bocage, un autre authentique pionnier.

« The Damnedest American Autobiography Ever Published ! » affichait sans vergogne le pavé publicitaire annonçant la sortie de « Really the Blues » signé Milton « Mezz » Mezzrow assisté de Bernard Wolfe. Un document assez exceptionnel si l’on veut bien passer sur les rotomontades de l’auteur, clarinettiste et, à l’époque, président de King Jazz. Une compagnie phonographique initiée par deux ingénieurs, John Van Beuren et Harry Houck, qui, selon leurs vœux, serait entièrement vouée au jazz « primitif, simple, direct, trépidant et envoûtant » tel que le définissait Mezz. Admirateur de Bechet qu’il considérait comme son alter ego musical, Mezzrow s’attacha ses services.

Sidney : « Pour moi, cette compagnie d’enregistrement valait cet orchestre Nouvelle-Orléans que je voulais avoir. Cette nouvelle marque fut donc créée et commença à enregistrer énormément. À la première séance, en août 1945, nous avons enregistré Gone Away Blues, Out of the Gallion, De Luxe Stomp, Bowin’ the Blues. Et d’autres morceaux ; il y avait pour cette séance Fitz Weston au piano, Pops Foster à la contrebasse et Kaiser Marshall à la batterie. C’étaient des disques dont on pouvait être fiers(1) ». Effectivement. Gone Away Blues et Out of the Gallion, deux compositions de Mezzrow, s’appuyaient sur un cadre thématique relativement défini par rapport aux variations sur le blues conduites sur l’instant. Une norme chez King Jazz, ainsi Bowin’ the Blues baptisé en raison de la partie de basse à l’archet que Pops Foster avait eu bien du mal à imposer à Mezz.

Reconnaître que le jeu de Bechet atteint à des sommets au long de cette séance relève de l’évidence. Par contre, si dans Gone Away Blues Mezzrow tire son épingle du jeu, la majorité du temps, il cumule notes approximatives, sonorité geignarde et imagination mélodique limitée.

Le temps ne fera rien à l’affaire. Au cours des deux parties de Really the Blues, Bechet, soutenu par Baby Dodds, s’envole ; Mezzrow suit tant bien que mal, plus heureux dans ses contrechants que dans ses solos. Chicago Function, I’m Speaking my Mind bénéficient de la présence de Sammy Price au piano qui avouera : « Je ne pense pas que Bechet ait jamais compris pourquoi Panassié considérait Mezzrow comme un grand clarinettiste. Et ainsi que j’ai pu m’en rendre compte, Sidney et Mezz ne furent jamais proches(2). » Pas plus aux États-Unis qu’à Paris, Bechet ne fit appel à Mezzrow. Il dira à propos de son obsession à se vouloir Noir : « Mezz aurait dû savoir que la race ne signifie rien - ce qui compte, c’est d’attraper les bonnes notes(3). »

Au vu des cafouillages et imprécisions de Mezzrow, Bechet n’eut pas le moindre scrupule à s’attribuer la direction des opérations. Ce qui permettra à Christian Béthune d’écrire : « Remarquons enfin au passage que, sans doute du fait de manque de répondant de Mezzrow dont la voix ne constitue pas pour lui un appui fiable, Bechet s’installe de manière radicale en position de soliste, abandonnant ainsi la partie du déchant d’où il faisait régner son ordre poétique. D’une façon tout à fait paradoxale, ces enregistrements King Jazz, censés faire référence à l’esthétique du jazz des origines, en estompaient ironiquement l’un des traits stylistiques dominants, à l’insu même de leur initiateur(4). »

Bechet poursuivait parallèlement sa collaboration avec Blue Note. Sur Save It Pretty Mama, il retrouve Art Hodes et dialogue avec le cornettiste Wild Bill Davidson, un musicien solide, au jeu étonnamment conciliable avec le sien au cours des improvisations collectives. Bechet en profitera pour signer un beau chorus dans le grave de la clarinette, instrument qu’il conserve lors de sa rencontre avec l’un de ses pairs, Albert Nicholas. Fabrice Zanmarchi : « La finesse d’Albert Nicholas est le pendant idéal à la fougue de Sidney Bechet dans un Old Stack O’Lee Blues bleuté à souhait, deux manières opposée de faire sonner l’instrument de bois(5). »

Aucune nuance ne restait étrangère à Bechet. À l’occasion d’un concert patronné par Blue Note au Town Hall de New York, accompagné par James P. Johnson, Pops Foster et Baby Dodds, China Boy lui sert de prétexte pour tirer un véritable festival pyrotechnique. Inspiré par le titre de la composition de David Raskin identique au prénom de sa nouvelle compagne, soutenu par un autre trio, Bechet devient, sur Laura, le chantre des passions romantiques.

En 1946, Bechet avait ouvert à son domicile - 178 Quincy Street, Brooklyn - , une école de musique. Mezzrow lui présenta Bob Wilber qui, plus qu’un élève, deviendra en quelque sorte le pupille de Sidney, l’escortant aussi bien au Jimmy Ryan’s qu’au cours d’expéditions nautiques hasardeuses, à bord du bateau à moteur que son professeur s’était offert.

Pour enregistrer six compositions originales de Bechet, Wilber convoqua quelques solides vétérans, de Jimmy Archey à Pops Foster en passant par Henry Goodwin – un ancien « Feetwarmer » - et Tommy Benford. Avant d’emboucher son soprano, Bechet récitait sur Love Me with a Feeling un texte de circonstance, accompagné magistralement par Bob Wilber à la clarinette et Dick Welstood au piano.

Un mois jour pour jour avant cette séance, Sidney Bechet entama une seconde carrière. À son insu. Salle Pleyel, le dimanche 8 mai 1949, le 2è Festival de Jazz débutait par un concert réunissant successivement Sidney Bechet et Charlie Parker, tous deux engagés par Charles Delaunay lors d’un voyage aux États-Unis. Initiative doublement audacieuse car Parker ne faisait pas l’unanimité parmi les amateurs et Sidney Bechet restait sous le coup d’une interdiction de séjour prononcée en 1928. La conséquence d’une condamnation à 15 mois de prison prononcée à l’issue du duel au pistolet qui l’avait opposé au banjoïste Mike McKendrick et avait fait, rue Fontaine, trois blessés dont un grave. Vingt ans après, Bechet bénéficiera seulement d’une autorisation de séjour temporaire. L’amnistie viendra plus tard. Difficilement.

La couverture du n°34 de Jazz Hot daté juin 1949, fut illustrée par une photo de Sidney Bechet coiffé d’une couronne. Dans son compte-rendu, André Hodeir écrivait : « Le grand triomphateur du Festival fut sans nul doute Sidney Bechet, dont chaque apparition sur scène a suscité une énorme vague d’enthousiasme […] Il joue avec une telle foi, une telle jeunesse, en dépit de ses cheveux blancs, et sa mimique semble tout à la fois si simple et si sincère, qu’on voit mal comment un public qui vient au Festival chercher de simples émotions ne lui accorderait pas ses faveurs. »

Lors du concert d’ouverture, la formation du jeune saxophoniste soprano Pierre Braslavsky avait accompagné Sidney. Le vendredi 13, ce fut le tour de Claude Luter et ses Lorientais ; une collaboration qui perdurera à partir du mois d’octobre, date du premier retour de Sidney Bechet. Un tournant majeur pour lui : dorénavant il était le chef incontesté d’un orchestre entièrement à sa dévotion, façonné selon ses désirs et dont aucun des membres n’aurait eu l’idée de rivaliser avec lui.

Pour la première fois en studio en compagnie de l’orchestre Luter, il enregistre Bechet’s Creole Blues, Buddy Bolden Story et Ce Mossieu qui Parlé. Une séance inaugurant son nouveau contrat avec Vogue. La naissance de ce qu’Alain Gerber désignait comme « ce son très particulier des séances françaises avec Luter qui appartient à notre imaginaire collectif et qui, à ce titre, est devenu irremplaçable ». Bechet puisait alors dans ses expériences passées. Le blues bien sûr - Bechet’s Creole Blues, Buddy Bolden Story - mais aussi, au travers de Ce mossieu qui parlé, la musique créole qu’il avait servie, une décennie plus tôt, au sein du « Haitian Orchestra » en compagnie de Willie Smith the Lion. Moulin à café ressuscitait les duos de clarinettes, montrant pour l’occasion que Claude Luter se révélait être un digne interlocuteur.

Les mélodies composées par Bechet porteront désormais des titres français et beaucoup d’entre elles rencontreront un beau succès comme En attendant le jour et Si tu vois ma mère. Par la grâce de Fernand Bonifay et de Mario Bua, Petite Fleur deviendra même une chanson défendue aussi bien par Mouloudji et Henri Salvador que par Tino Rossi et Annie Cordy. Selon l’usage en vigueur à La Nouvelle Orléans des origines, le vieux maître faisait flèche de tout bois. Georges Brassens passe-t-il en attraction au Vieux Colombier dont il a fait son port d’attache ? Il enregistre La Cane de Jeanne, Le Fossoyeur, Brave Margot.

Omniprésent, Bechet fait irruption en des lieux où le jazz n’avait guère droit de cité. Le 9 février 1951, Luter et lui débutent à l’ABC au même programme qu’André Claveau. Sur la scène de Bobino, il précéde Fernand Raynaud et Catherine Sauvage. À l’Olympia, son nom figure à l’affiche en compagnie de ceux de Mouloudji et de Nicole Louvier, puis de Charles Aznavour. Son mariage à Juan-les-Pins, à grand renfort de calèches et de tombereaux de fleurs, fut couvert par les « Actualités Françaises » en 1951. Presque chaque foyer finit par posséder un de ses 45 tours.

Sans répit, Bechet, infatigable, sillonne la France. Feuilleter le carnet dans lequel Charles Delaunay notait ses engagements donne le vertige. À certaines périodes de l’année, il donne pratiquement un concert par jour en des villes différentes. Ainsi, lui-même et l’orchestre Claude Luter jouent à Tanger, Casablanca, Fez, Oran, Alger, Tunis (Jazz Hot, octobre 1952). Trois ans plus tard, au cœur de l’été Bechet est attendu à Perros Guirec (le 11), Cherbourg (le 14), Coutain-ville (le 15), Deauville (le 16), Sables d’Or (le 20), Cabourg (le 22), Chate-lail-lon (le 24), St-Jean-de-Luz (les 30, 31 juillet et 1er août), Hossegor (le 3), etc…

Il ne refuse jamais de se produire, même pour des occasions comme la fête de la Sainte Anne à Vallauris. Il tourne aussi des films, « Série Noire » dans lequel Erich Von Stroheim tient une fois de plus le rôle du méchant ou « Ah, quelle équipe » interprété par quelques-uns de ces seconds rôles qui ont fait le piment d’un certain cinéma français. Aucune de ses productions ne figurera dans les cinémathèques mais le public les apprécie. Le 17 mars 1955, à l’Opéra de Paris, René Coty, alors président de la République, assiste à une version de « La nuit est une sorcière », un ballet composé par Bechet.

Trop, c’est trop, les intégristes commencent à faire la fine bouche. Sidney Bechet est popu-laire et, comme tout artiste bénéficiant d’une reconnaissance hors du sérail, il devient suspect. Erroll Garner et Dave Brubeck en sauront quelque chose… Dans une tribune intitulée « Le cas Sidney Bechet », publiée dans le numéro 101 de Jazz Hot durant l’été 1955, d’aucuns l’accusèrent sans ambage de vendre une marchandise qui n’était plus du jazz. René Urtreger répliquera : « L’amateur de jazz reproche peut-être à Bechet de jouer La Complainte des Infidèles, mais si ce morceau était intitulé Infidels Complaint, cela passerait sans doute tout seul. » On ne saurait mieux dire. Vu de l’autre bord, c’est-à-dire, dans le Bulletin du Hot Club de France dirigé par Hugues Panassié, Bechet n’était pas mieux considéré.

Lorsque ses disques sont chroniqués, ils le sont avec une certaine condescendance. Luter et ses musiciens ayant rendu leur tablier, Bechet se produit maintenant avec l’orchestre d’un autre clarinettiste, André Reweliotty. Y figure l’un de ses interlocuteurs favoris, le trompettiste Guy Longnon, débauché de la formation Luter. Pour entièrement à sa dévotion que soit cet ensemble, Bechet n’en grave pas moins en sa compagnie quelques perles, plus nombreuses que les censeurs ne veulent l’avouer. Par exemple Temperamental aux curieux accents mélodramatiques, Passport to Paradise nostalgique à souhait et Amour perdu, l’une de ses plus belles compositions.

L’ostracisme envers la production de Sidney débouchera sur une situation à tout le moins paradoxale. Dans les « Critiques croisées » de Jazz-Hot, l’un de ses albums les plus passionnants sera qualifié de « sans intérêt » par deux participants, le même nombre le jugera seulement « à écouter », la mention « bon disque » lui sera attribuée doublement ; aucun « Très bon disque », ni « Réussite exceptionnelle ». Dans sa chronique, Michel Delaroche alias Boris Vian ne sera guère plus enthousiaste. Sur la sellette, rien moins que la rencontre Sidney Bechet – Martial Solal.

Charles Delaunay : « Arrivé en avance au studio où Sidney Bechet enregistrait cet après-midi là, il assista à la fin d’une séance et entendit ainsi un pianiste avec lequel il manifesta sur le champ le désir d’enregistrer un jour. Ce pianiste n’était autre que Martial Solal, l’un des plus brillants représentants français du jazz moderne. » Faut-il rappeler que Barney Wilen se souvint que Sidney Bechet avait émis le vœu de graver un album en sa compagnie ?

Martial Solal : « J’ai voulu prouver qu’il pouvait y avoir coexistence entre les tenants du be-bop et les partisans du jazz traditionnel. La séance s’est déroulée dans la plus grande simplicité et très rapidement. Une seule prise par morceau. J’ai un peu restreint mes choix harmoniques pour éviter de gêner Bechet(6). »

Les thèmes choisis étaient des « standards », un répertoire dans lequel Sidney avait déjà largement puisé ; Lloyd Thompson et Al Levitt tenaient la basse et la batterie, Pierre Michelot et Kenny Clarke les relayant par la suite. The Man I Love inspire un passionnant dialogue soprano/piano ; sur All the Things You Are, contrairement à toute logique, nulle solution de continuité n’intervient entre l’exposition de Sidney et le chorus de Martial Solal et, à propos de It Don’t Mean a Thing, il n’est pas exagéré de parler de chef-d’œuvre.

La maison Vogue pérennisa quelques autres rencontres ponctuelles. Si Lil Armstrong n’est ni la plus grande chanteuse, ni la meilleure pianiste qui soient, avec l’aide de Zutty Singleton, sur Big Butter and Egg Man et Limehouse Blues elle fournit à Bechet un soutien solide sur lequel il prend visiblement plaisir à broder. Une séance respirant la bonne humeur qui, selon Charles Delaunay, imposa un nombre de prises particulièrement élevé…

Lorsque les « Bluesicians » de Sammy Price effectuèrent une tournée en France, Bechet vint les rejoindre au studio. Nombre de ses anciens partenaires y figurant, il n’eut aucun scrupule à prendre les commandes. Sur Tin Roof Blues, l’élégance du jeu de clarinette pratiqué par Herb Hall contraste opportunément avec la hargne qui sous-tend à cette occasion le jeu de Sidney.

Lors du Festival de Jazz 1958, Teddy Buckner était venu à Cannes participer à diverses jam-sessions programmées ; parfois en compagnie de Sidney Bechet. Sur le chemin de Knokke-le-Zoute où se poursuivaient les festivités cannoises, tous deux furent détournés vers la Salle Wagram. Les y attendaient le tromboniste Christian Guérin et le bassiste Roland Bianchini, venus de l’orchestre Luter, Eddie Bernard au piano et, à la batterie Kansas Field, alors free lance dans la capitale. Une configuration propre à mettre en boîte l’une de ces « séances jam-session » chères aux labels français. Contre toute attente, il en ressortira une version, remarquable par sa cohésion, d’un thème assez inhabituel pour Bechet, I Can’t Get Started. Sereinement, délicatement, il en expose la mélodie avant de laisser la parole à Teddy Buckner dont le chorus de trompette avec sourdine relève d’une même inspiration.

Pour parisien qu’il fût, Sidney Bechet n’en effectuait pas moins quelques voyages aux Etats-Unis, ne serait-ce que pour remplir le contrat moral qui le liait à Blue Note. En 1951, à la tête de ses « Hot Six », il se retrouvait en terrain connu, Pops Foster et Manzie Johnson l’avaient déjà accompagné à maintes reprises, le trompettiste Sidney DeParis avait appartenu aux « New Orleans Feetwarmers » et Jimmy Archey n’était pas un inconnu. De conserve, ils offriront une version roborative de Original Dixieland One Step où s’affiche une conception du jeu collectif assez différente de celle que Bechet imposait à ses accompagnateurs européens.

Deux ans plus tard sera mise en boîte la dernière séance Blue Note. Pour en constituer la rythmique, Bechet avait téléphoné depuis Paris à Johnny Blowers, un batteur tout-terrain ayant travaillé aussi bien avec Armstrong et Eddie Condon qu’aux côtés d’Ella Fitzgerald et de Frank Sinatra. La section mélodique fut constituée, en sus de Sidney, de Jimmy Archey une fois encore et du trompettiste Jonah Jones. À cette époque disciple inconditionnel de Satchmo, ce dernier sert un exposé en demi-teinte de Black and Blue accompagné par Buddy Weed au piano. Visiblement impressionné, Bechet conserve dans son improvisation le ton doux-amer qui imprègne la chanson d’Andy Razaf et Fats Waller.

Trois mois plus tard, Sidney est enregistré en public à Boston, dans le club dirigé par George Wein qui fera ce commentaire : « Jazz at Storyville fut un album impressionnant, rassemblant du très bon Bechet et de l’excellent Vic Dickenson. Peu de musiciens savaient aussi bien que Dickenson jouer avec Bechet et le disque le montre(7). » Manifestement heureux de se trouver en compagnie du tromboniste, Bechet, détendu, signe un Honeysuckle Rose lumineux.

Au cours de la séance « Ce mossieu qui parlé - Buddy Bolden Story - Bechet Creole Blues » avait été enregistré Les oignons. Une chanson créole louisianaise traditionnelle dont Bechet s’attribua la paternité, au grand déplaisir d’Albert Nicholas qui l’avait gravée deux ans plus tôt. Les Oignons devinrent un énorme tube, tout comme Petite Fleur et, le 19 octobre 1955, Bechet reçut le Disque d’Or récompensant son 1 000 000ème disque vendu. Une cérémonie qui se déroulait à l’Olympia, suivie d’un concert gratuit. Moins de 2 000 places pour 3 000 postulants. Ce qui devait arriver, arriva. Le music hall de Bruno Coquatrix subit quelques dégradations. En les évoquant, la presse bien-pensante ne manqua pas l’occasion de stigmatiser les fans de jazz, parlant de dégâts s’élevant à deux millions d’anciens francs. Charles Delaunay reçut une facture de 4473,30 francs (anciens) très exactement.

Évaluer le nombre d’interprétations publiques des Oignons reviendrait à comptabiliser la totalité de concerts donnés par Bechet et l’orchestre Luter. En tenant compte des bis éventuels. Le 12 décembre 1958, à la fin de sa toute dernière séance d’enregistrement consacrée à des chants de Noël, Sidney Bechet en offrit une ultime version. Différente, émouvante par sa sobriété, en forme d’adieu. Jean-Claude Pelletier : « La dernière fois que j’ai enregistré avec Sidney, c’était en décembre dernier. On savait que Sidney était très fatigué et je ne m’attendais pas à trouver en lui cette puissance et cette vitalité qui l’animaient dès qu’il jouait(8). »

Lorsque Sidney Bechet s’éteignit le 14 mai 1959, sa popularité avait quelque peu fait passer au second plan une vérité que Duke Ellington s’efforça de rappeler : « Mais nous ne devons pas oublier le plus grand : Bechet ! Le plus grand de tous les créateurs; Bechet, le symbole du jazz »(9).

Alain TERCINET

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

(1) Sidney Bechet, « La musique, c’est ma vie » (Treat It Gentle), trad. Yvonne et Maurice Cullaz, La Table Ronde, Paris, 1977.

(2) John Chilton, « Sidney Bechet – The Wizzard of Jazz », MacMillan Press, Londres, 1987.

(3) comme (2)

(4) Christian Béthune, « Sidney Bechet », collection Eupalinos, Parenthèses, Marseille, 1997.

Déchant : Dans les débuts de la polyphonie, partie supplémentaire ornementale composée ou parfois improvisée qui s’ajoute au dessus du ténor. (Jacques Siron, Dictionnaire des mots de la musique , Outre Mesure). À prendre ici dans le sens de contrechant.

(5) Livret de « Sidney Bechet – The Complete American Masters 1931-1953 », Universal.

(6) Pascal Anquetil, « Martial Solal l’équilibriste », Télérama Spécial Jazz, juin 1994.

(7) George Wein avec Nate Chinen, « Myself among Others – A Life in Music », Da Capo Press, 2003.

(8) « Sidney Bechet », Jazz Hot n° 144, juin 1959.

(9) Stanley Dance « Duke Ellington par lui-même et ses musiciens », (The World of Duke Ellington), trad. Antoinette Roubichou, Filipacchi, 1976.

SIDNEY BECHET Vol. 2 – RANDOM TRACKNOTES

When Sidney Bechet went into WOR’s New York studios on December 20th 1944, it had been more than two years since the Blues in the Air recording that closes the previous volume in this series. In the interval he’d done just one official session, with three sides for release on V-Discs… James Caesar Petrillo, the President of the American Federation of Musicians, had decreed a recording ban that ran from August 1942 until November 1944.

RCA Victor had taken advantage of the ban to terminate Bechet’s contract, and Sidney went back to Alfred Lion, one of his former employers. Gone were the “New Orleans Feetwarmers” (where no trumpeter had been found as a permanent replacement for Tommy Ladnier), and in their stead came the “Blue Note Jazzmen,” a similar band who got off to an excellent start: on Blue Horizon, an original composition where he’s the only soloist on clarinet, Bechet pulls off one of his best performances on a slow tempo piece.

A month later he tackled High Society, taking up Alphonse Picou’s famous solo in masterful fashion while inventing multiple variations and descants behind Max Kaminsky, a trumpeter met in Eddie Condon’s Floor Shows who, quite visibly, inspired him. On Weary Blues, however, playing soprano — a more dominant instrument than the clarinet —, Bechet chooses to blend into the ensemble-playing, an approach he would hardly cultivate again.

By way of an overture to Buddy Bolden Blues, Sidney told Claude Luter that in 1910, Bunk Johnson had come looking for him (he was still living with his parents) and taken him off to play with the Eagle Band; Sidney said that he was twelve at the time… By 1934, Bunk Johnson had practically given up music due to problems with his health. Four years later, while doing research for their book called “Jazzmen”, Bill Russell and Frederic Ramsey rediscovered Bunk in New Iberia, Louisiana, where he was driving a tractor in the rice-fields for $1,50 a day. In 1942, sporting new braces on his teeth as well as carrying a new trumpet, Bunk Johnson, considered the last living representative of pure, seminal jazz, made his first record. He later went to San Francisco and joined Lu Watter’s Yerba Buena Jazz Band, who were at the origins of the “New Orleans Revival” taking place on the West Coast.

On his way through New Orleans one day, Bechet heard Bunk playing at a concert, and Sidney’s fond memories of the Eagle Band prompted him to ask the trumpeter if he’d like to accompany him to New York. Bunk already had plans to go there with his own orchestra, and saw it as a fine opportunity for New Yorkers to get to know him better. The two new partners appeared on March 10th at Jimmy Ryan’s club thanks to Milt Gabler, but it was Alfred Lion who actually recorded him that night, along with Cliff Jackson and Manzie Johnson as the piano/drums replacements for Hank Duncan and Kaiser Marshall. They played the music the way Bunk Johnson intended it to be heard, with its share of collective improvisations. Bechet had been totally in favour of the project, and does nothing to steal the limelight either in Days Beyond Recall or in Up in Sidney’s Flat, two of his own compositions. The fact that his solos outdo those of his partner is another matter entirely.

Their relationship took a downturn in the course of a lengthy stay at the Savoy Cafe in Boston. The trumpeter had more than a passing taste for whiskey and it often left him incapable of playing, a fact that Bechet found exasperating even though he was totally foreign to temperance leagues himself… Bechet replaced Bunk Johnson first with Johnny Windhurst (aged merely 18), whom he’d met when playing with Eddie Condon, and then Peter Bocage, another genuine pioneer.

“The Damnedest American Autobiography Ever Published!” was the unabashed claim for “Really the Blues”, written by Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow with the assistance of Bernard Wolfe. The book is rather exceptional if you turn a blind eye to the bragging of its author, a clarinettist by trade and, at the time, President of the King Jazz record-company set up by two engineers (John Van Beuren and Harry Houck) to devote its energies to the jazz defined by Mezz as “primitive, simple, direct, thrilling and spellbinding.” Mezz admired Bechet, considering him as his alter ego. He hired him. According to Sidney, “That company, it was as good as having that New Orleans band I wanted. Well, the new label really got under way and started recording like crazy. On the first session in August 1945 we did Gone Away Blues, Out of the Gallion, De Luxe Stomp, Bowin’ the Blues and some others; we had Fitz Weston on piano, Pops Foster and Kaiser Marshall. They were records you could feel proud of.”(1) Indeed he could. Gone Away Blues and Out of the Gallion, two of Mezzrow’s compositions, had a thematic base defined in relation to variations on the blues that were executed in the moment. It was a norm at King Jazz, and that gave rise to this Bowin’ the Blues that owes its name to the bowed bass part that Pops Foster had a lot of difficulty getting Mezz to accept. It’s no great achievement to recognize that throughout this session, Bechet’s playing reaches the heights. On the other hand, while Mezzrow comes out well in Gone Away Blues, he spends most of the time elsewhere accumulating approximate notes with a sound that whines and a melodic imagination that shows its limits.

Things didn’t change over time. In the both parts of Really the Blues, Bechet simply flies (backed by Baby Dodds), with Mezzrow hanging on as best he can, happier to play in counterpoint rather than solo. Chicago Function and I’m Speaking my Mind benefit from the presence of Sammy Price on piano who confessed, “I don’t think that Bechet could ever understand why Hugues Panassié thought Mezzrow was a great clarinettist. As I saw it, Sid and Mezzrow were never close… ”(2) Bechet never summoned Mezzrow at home, no more than he did in Paris, and, on the subject of Mezzrow’s obsession with being Black, he observed, “Mezz should know that race does not matter – it is hitting the notes right that counts.”(3)

Given the confusion to be found in Mezzrow — sometimes his playing was a shambles — Bechet had no scruples in appointing himself to head the operation, leading Christian Béthune to write, “Finally, let’s not forget in passing that, no doubt due to the lack of repartee in Mezzrow, whose voice he didn’t consider especially reliable, Bechet installs himself in the soloist’s position in radical fashion, thereby abandoning the part of the descant from which he caused his own poetic order to reign. In a totally paradoxical manner, these King Jazz recordings, which supposedly refer back to the original jazz aesthetic, ironically blurred one of its dominant stylistic traits without even their initiator being in any way aware of it.”(4)

In parallel Bechet continued his association with Blue Note. For Save It Pretty Mama he went back to Art Hodes and had a conversation with cornet-player Wild Bill Davidson, a solid musician whose playing is astonishingly compatible with his own during the collective improvisations; Bechet would take advantage of that to play a beautiful chorus in the clarinet’s lower register, and kept that instrument for his encounter with one of his peers, Albert Nicholas. As Fabrice Zanmarchi points out, “The finesse of Albert Nicholas is the ideal match for the fieriness of Sidney Bechet in an Old Stack O’Lee Blues that’s blue to perfection: two opposite ways of causing the woodwind instrument to sing.”(5)

No nuance remained a secret for Bechet. At the Blue Note-sponsored concert held at New York’s Town Hall, with James P. Johnson, Pops Foster and Baby Dodds accompanying Sidney, China Boy serves as a pretext for genuine pyrotechnics while Laura (inspired by the title of the David Raskin composition, identical to the name of his new fiancée) sees Bechet, this time with another trio, transformed as the bard of romantic passion.

Bechet lived at 178 Quincy Street in Brooklyn, and in 1946 he opened a music school there, where Mezzrow introduced Bob Wilber to him; more than Sidney’s pupil, Bob became a kind of ward, escorting him both to Jimmy Ryan’s and on some perilous nautical trips they made in the motor-boat his music-teacher bought for himself. To record six original Bechet compositions Wilber convened a few solid veterans, from Jimmy Archey to Pops Foster via Henry Goodwin – a former “Feetwarmer” – and Tommy Benford. Before putting his soprano to his lips, Bechet would recite an appropriate text over Love Me with a Feeling, masterfully accompanied by Bob Wilber on clarinet and Dick Welstood on piano.

One month to the day before that session, Sidney Bechet began a second career. He was blissfully unaware of it. At the Salle Pleyel in Paris, on Sunday May 8th 1949, the 2nd French “Festival de Jazz” began with a concert featuring Sidney Bechet and Charlie Parker in succession, both of them having been signed up for the event by Charles Delaunay during a trip to America made by the latter. The audacity of Delaunay’s initiative was double: for one, Parker wasn’t every fan’s favourite, and as for Sidney Bechet, he was still an “illegal alien” after being banned from visiting France since 1928… when he’d been sentenced to 15 months in jail after a pistol-duel with banjo-player Mike McKendrick, during which incident (on the rue Fontaine in Paris), three people had been injured, one seriously. Twenty years on, Bechet would be allowed into the country on a temporary visa; amnesty would be granted later. But not without difficulty.

The cover of the “Jazz Hot” issue N° 34 dated June 1949 was illustrated by a photo of Sidney Bechet wearing a crown. André Hodeir wrote in his review: “The triumphant victor of the Festival was no doubt Sidney Bechet, every one of whose appearances on the stage aroused an enormous wave of enthusiasm […] He plays with such conviction, such youth-fulness despite the whiteness of his hair, and with gestures seemingly so simple and at the same time so sincere, that it is hard to see how he could fail to find favour with an audience come to the Festival in search of simple emotions.”

In the opening concert, it was the band of young soprano saxophonist Pierre Braslavsky that accom-panied Sidney. On Friday 13th it was the turn of Claude Luter and his “Lorientais”; that collaboration, begun in October (the date of Sidney Bechet’s first return to France) would last a while. It was a major turning-point for him: from now on he was the uncontested leader of an orchestra entirely devoted to him in every way, a band shaped by his own desires, and where the idea of competing with Sidney never crossed the mind of any of its members.

Accompanied in a studio by the Claude Luter orchestra for the first time, Sidney recorded Bechet’s Creole Blues, Buddy Bolden Story and Ce Mossieu qui Parlé. The session inaugurated Sidney’s new contract with Vogue, and saw the birth of what Alain Gerber designated as “that very particular sound of the French sessions with Luter that belongs to our collective imagination and, as such, has become irreplaceable.” Bechet was then drawing on past experiences. The blues, of course — Bechet’s Creole Blues, Buddy Bolden Story — but also, through Ce mossieu qui Parlé, the Creole music he’d served a decade earlier when playing in the “Haitian Orchestra” in the company of Willie “The Lion” Smith. Moulin à café resuscitates those old clarinet duets, and reveals at the same time that Claude Luter always showed himself an extremely worthy partner.

The melodies Bechet composed would now have French titles, and many of them were very successful, like En attendant le jour and Si tu vois ma mère for example. Thanks to Fernand Bonifay and Mario Bua, Petite Fleur even turned into a song, and it was sung not only by Mouloudji and Henri Salvador, but also by the likes of Tino Rossi or Annie Cordy. Keeping to a tradition that went back to the early days in New Orleans, the wily old master jumped on anything available: Sidney chose Le Vieux Colombier as one of his regular haunts, and when Georges Brassens came to sing there, Sidney instantly recorded Georges’ songs La Cane de Jeanne, Le Fossoyeur, Brave Margot…

Bechet was omnipresent, popping up even in places where jazz was barely allowed to hang its hat. On February 9th 1951, he and Luter opened at the ABC on the same bill as André Claveau; at Bobino he would take the stage before Fernand Raynaud and Catherine Sauvage; and at the Olympia, his name was on posters alongside Mouloudji and singer Nicole Louvier, and then Charles Aznavour. When Sidney got married in Juan-les-Pins (1951), there were all the frills — horse-drawn buggies and cartloads of flowers — and the event featured in the film magazine “Actualités Françaises”. By the end, almost every household in the country would have one of his singles…

Bechet never seemed to rest, criss-crossing the country tirelessly. It makes you dizzy just to flip through the notebook where Charles Delaunay jotted all his bookings; there were certain periods in the year when Sidney was playing a concert practically every day in different towns. If you take a look at the October ’52 issue of “Jazz Hot”, you see that he was playing with Claude Luter and his orchestra in Tangiers, Casablanca and Fez (Morocco), and then Oran, Algiers and Tunis. Three years later he was still at it: in July alone he was expected in Perros Guirec (11th), Cherbourg (14th), Coutainville (15th), Deauville (16th), Sables d’Or (20th), Cabourg (22nd), Chatelaillon (24th) and Saint-Jean-de-Luz (30th, 31st, and then August 1st) with yet another gig in Hossegor on the 3rd…

Nor did Sidney ever turn down an offer to play, not even if it was Sainte Anne’s Day in Vallauris or some other, minor event. And then there were his films… Sidney appeared in “Série Noire” (with Erich Von Stroheim playing yet another “bad guy” role), and in “Ah, quelle équipe” [loosely translated, something like “Oh, what a crew!”], with a cast of actors well-known for their supporting roles in French films where people dressed as sailors… None of Sidney’s films was ever screened in art-house cinemas, but audiences liked them. Nor did he limit himself to films: on March 17th 1955, René Coty, then President of the French Republic, went to the Paris Opera to see a version of the ballet “La nuit est une sorcière”. The composer was Bechet.

It may have been too much. Fundamentalists began to frown. Sidney Bechet was popular and, like all artists earning recognition from outside one sphere, became suspect in another. Erroll Garner and Dave Brubeck would discover that for themselves… In a forum entitled “The case of Sidney Bechet” published in “Jazz Hot” (issue N°101, summer ’55), there were those who bluntly accused Bechet of selling merchandise that was no longer jazz. René Urtreger’s reply was, “Perhaps jazz fans do reproach Bechet for playing La Complainte des Infidèles, but if the tune was called Infidels Complaint they wouldn’t bat an eyelid.” Indeed. Seen from the other side of the ring, i.e. the Bulletin of the Hot Club de France (the newsletter run by Hugues Panassié), Bechet was held in no higher esteem. When people reviewed his records they did so condescendingly.

Luter and his musicians had thrown in the towel, and so Bechet was now playing with the band of another clarinettist, André Reweliotty. This ensemble also featured one of his favourite partners, trumpeter Guy Longnon, who’d been lured away from the Luter outfit. Unquestionably, the whole orchestra was devoted to Bechet, but the latter still recorded a few pearls in their company, and there were more than the censors cared to admit. Temperamental for instance, with its curious, melodramatic accents; Passport to Paradise, with as much nostalgia as you could wish for; and one of his most beautiful compositions, Amour perdu.

The ostracism around Sidney’s work resulted in a paradox, to say the least. In the section of “Jazz Hot” called “Cross-Critics”, one of his most exciting albums was qualified as “without interest” by two participants, with the same number judging it to be “worth a listen”, while it was twice noted as a “good record”; not a hint of “very good record” or “exceptional achievement”. In his review, “Michel Delaroche” (alias Boris Vian) hardly showed more enthusiasm. The subject of all this attention was an encounter between Bechet and Martial Solal, no less.

Charles Delaunay: “Having come down early to the studio where he was to record that afternoon, Sidney Bechet was present at the end of one session and so he was able to hear the pianist; at once he manifested the desire to record with him one day. That pianist was none other than Martial Solal, one of the most brilliant representatives of modern jazz in France.” And need we remind anyone Barney Wilen remembered Bechet saying he wanted to record with him?

Martial Solal: “I wanted to prove that bebop suppor-ters and traditional jazz partisans could coexist. The session went off as simply as could be, all of it very quickly. A single take for each piece. I restricted my harmonic choices a little to avoid bothering Bechet.”(6)

The themes they chose were “standards”, a repertoire on which Sidney had already drawn handsomely; Lloyd Thompson and Al Levitt played bass and drums, later relayed by Pierre Michelot and Kenny Clarke. The Man I Love inspires a thril-ling dialogue between soprano and piano; on All the Things You Are, contrary to all logic, the transition between Sidney’s statement of the theme and the chorus played by Martial Solal is absolutely seamless; and as for It Don’t Mean a Thing, it’s no exaggeration to say it’s a masterpiece.

Vogue Records made sure a few other en-counters went down for posterity. Lil Armstrong may not have been the greatest singer ever, nor the greatest pianist, but with help from Zutty Singleton she gives Bechet solid support on Big Butter and Egg Man and Limehouse Blues, where Sidney visibly takes pleasure in the embroidery. It was a particularly good-humoured session; according to Charles Delaunay, it also necessitated a particularly high number of takes…

When Sammy Price and his “Bluesicians” were touring in France, Bechet went down to join them in the studio. With a number of his former partners present, he had no qualms about taking charge of the proceedings. On Tin Roof Blues, the elegance of Herb Hall’s clarinet playing provides a timely contrast to the fierce determination shown by Sidney on this occasion.

The 1958 Jazz Festival in Cannes saw trumpeter Teddy Buckner taking part in various jam sessions on the programme, sometimes in Bechet’s company. The festivities continued in Knokke-le-Zoute, and on the way up from Cannes, both musicians made a detour via the Salle Wagram. Waiting for them there were trombonist Christian Guérin and bassist Roland Bianchini (both from Luter’s orchestra), pianist Eddie Bernard and, on drums, Kansas Field, who was then freelancing in the French capital. It was the right kind of line-up to record what French labels liked to call a “jam-session session”. Against all expectations, it produced a remarkably cohesive version of a theme that was rather unusual for Bechet, I Can’t Get Started. Serenely and delicately, he states the melody before handing over to Teddy Buckner, who plays an inspired chorus in exactly the same vein using a mute.

However much of a Parisian Bechet may have been, it didn’t stop him making several trips to The United States, even if only to honour the moral contract which bound him to Blue Note. Fronting his “Hot Six” in 1951, he found himself on familiar ground: Pops Foster and Manzie Johnson had already accompanied him on several occasions, while trumpeter Sidney DeParis had been one of the “New Orleans Feetwarmers”, and Jimmy Archey was no foreigner either. Together they would come up with a bracing version of Original Dixieland One Step that displays a rather different concept of collective playing from the one that Bechet imposed on his European accompanists.

The last session for Blue Note came two years later. To put a rhythm-section together, Bechet placed a call from Paris to Johnny Blowers, an “all-weathers” drummer just as much at home with Armstrong and Eddie Condon as he was when working with Ella Fitzgerald or Frank Sinatra. To play the melody lines, in addition to Sidney there was Jimmy Archey again, and trumpeter Jonah Jones. At the time, the latter was a stalwart disciple of Satchmo, and here he serves up a low-key exposé of Black and Blue accompanied by Buddy Weed on piano. Visibly impressed, Bechet plays an improvisation that preserves the bittersweet tone of this song by Andy Razaf and Fats Waller.

Three months later Sidney was recorded in front of an audience in Boston at the club run by George Wein, who had this to say: “’Jazz at Storyville’ was an impressive record featuring some very good Bechet, and some excellent Dickenson. Few people know how to play with Bechet like Dickenson, and this record was ample proof.”(7) Manifestly happy to be in the trombone-player’s company, a relaxed Sidney Bechet executes a luminous performance of Honeysuckle Rose.

In the course of the same session that produced Ce mossieu qui parlé / Buddy Bolden Story / Bechet Creole Blues saw the recording of the title Les Oignons, a traditional Creole song from Louisiana of which Bechet claimed to be the father, much to the distaste of Albert Nicholas who’d recorded it two years earlier. Les Oignons went on to become an enormous hit, just like Petite Fleur, and on October 19th 1955, Bechet received a Gold Record to celebrate the sale of one million records. They gave him the award in a ceremony at the Olympia that was followed by a free concert. There were fewer than 2000 seats available, and when the demand rose to over 3000, the inevitable happened: the famous Parisian music hall of Mr Bruno Coquatrix suffered some damage. Right-thinking conformists in the press didn’t fail to seize the opportunity to stigmatize jazz fans, mentioning damage amounting to some two million Francs. The bill sent to Charles Delaunay was for 4473,30 Francs precisely. A list of Bechet’s public performances of Les Oignons would be as long as the number of concerts Bechet gave with Claude Luter and his orchestra. Encores included. On December 12th 1958, at the end of his very last session devoted to Christmas songs, Sidney Bechet played an ultimate version. It was different, moving in its sobriety, and it took the form of a farewell. Jean-Claude Pelletier said, “The last time I recorded with Sidney was last December. W knew Sidney was very tired, and I didn’t expect to hear that power and vitality he had in him as soon as he started playing.”(8)

When Sidney Bechet passed away on May 14th 1959, his popularity had somewhat eclipsed a truth that Duke Ellington took care to remind us of, saying, “But we mustn’t leave out the greatest – Bechet! The greatest of all the originators; Bechet, the symbol of jazz!”(9)

Alain TERCINET

© 2018 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

(1) Sidney Bechet, “Treat It Gentle”, Da Capo Press, 2002.

(2) John Chilton, “Sidney Bechet – The Wizard of Jazz”, Da Capo Press, 1996.

(3) ibid. (2)

(4) Christian Béthune, “Sidney Bechet”, collection Eupa-linos, Parenthèses, Marseille, 1997. Descant: not to be taken here as “an independent treble melody sung or played above a basic melody”; here the sense is “counterpoint”.

(5) Cf. booklet, “Sidney Bechet – The Complete American Masters 1931-1953”, Universal.

(6) Pascal Anquetil, “Martial Solal l’équilibriste”, in “Télé-rama Spécial Jazz”, June 1994.

(7) George Wein with Nate Chinen, “Myself among Others – A Life in Music”, Da Capo Press, 2003.

(8) “Sidney Bechet”, Jazz Hot N° 144, June 1959.

(9) Stanley Dance, “The World of Duke Ellington”, Da Capo Press, 2000.

« ON VOIT BIEN QU’IL EST FOU DE SON ART, CET HOMME, QUE LA MUSIQUE EST POUR LUI FONCTION VITALE. COMME ON AIMERAIT QUE TOUS LES MUSICIENS FUSSENT COMME LUI. »

ALFRED LOEWENGUTH (violoniste, prestigieux interprète de Ravel et Debussy, entre autres)

“HE’S MAD ABOUT HIS ART, THIS MAN; YOU CAN SEE THAT, FOR HIM, MUSIC IS ONE OF HIS VITAL FUNCTIONS. HOW WE’D LOVE ALL MUSICIANS TO BE LIKE HIM!”

ALFRED LOEWENGUTH (violinist known for his prestigious performances of Ravel and Debussy, among others)

CD 1 (1944-1949)

SIDNEY BECHET BLUE NOTE JAZZMEN (NYC, 20/12/1944 & 21/01/1945)

1 BLUE HORIZON 4’28

2 HIGH SOCIETY 3’37

3 WEARY BLUES 4’21

BUNK JOHNSON & SIDNEY BECHET’S BAND (NYC, 10/03/1945)

4 DAYS BEYOND RECALL 4’51

5 UP IN SIDNEY’S FLAT 4’23

MEZZROW – BECHET QUINTET (NYC, 29 & 30/08/1945)

6 BOWIN’ THE BLUES 2’47

7 GONE AWAY BLUES 2’43

8 OUT OF THE GALLION 2’31

ART HODES HOT FIVE (NYC, 12/10/1945)

9 SAVE IT, PRETTY MAMA 3’10

THE BECHET – NICHOLAS BLUE FIVE (NYC, 12/02/1946)

10 OLD STACK O’ LEE BLUES 4’14

JAZZ AT TOWN HALL (NYC, 21/09/1946)

11 CHINA BOY 3’59

SIDNEY BECHET QUARTET (NYC, 31/07/1947)

12 LAURA 3’09