- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

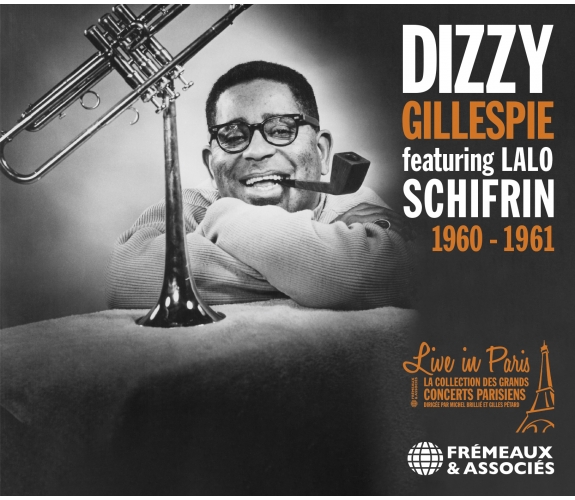

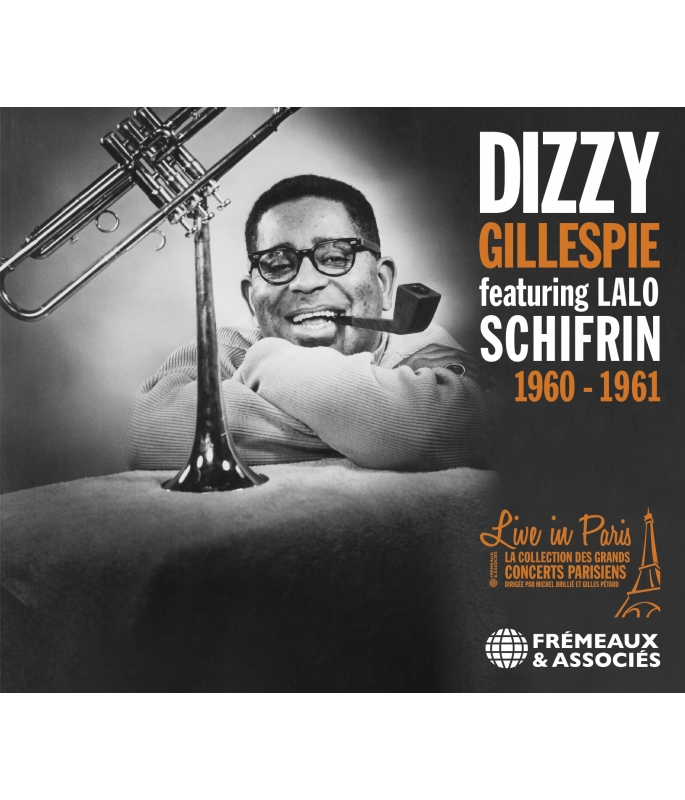

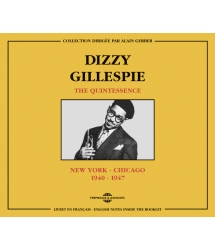

FEATURING LALO SCHIFRIN

DIZZY GILLESPIE

Ref.: FA5843

EAN : 3561302584324

Artistic Direction : Michel Brillié et Gilles Pétard - Livret : Michel Brillié

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 42 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

FEATURING LALO SCHIFRIN

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- - Recommandé par Le Monde

Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was a genuine luminary, one of the great modernizers of jazz, and as early as the forties he had already introduced Afro-Cuban rhythms into the genre. A decade later, the US State Department sent him round the world as an ambassador, notably to South America where he took advantage of his journey to pursue his quest for Latin rhythms of African origins. And in Argentina he met a young pianist and composer named Lalo Schifrin, who wrote an orchestral suite for Dizzy that he named “Gillespiana.” It became a great standard, and its first live performance was never released… until now. Recorded in 1960 and 1961, the sounds in this set provide marvellous testimony of the Latin Jazz trend that was imminent: this music was the first warning of the tidal wave called bossa nova that would hit America within months. And it provided a whole new generation with an immense groove.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX

The Live in Paris collection by Michel Brillié allows listeners to hear previously-unreleased recordings (made at concerts and private- or radio-sessions) by the great 20th stars in jazz, rock & roll and song. These “live” takes, and the artists’ rapport with their audiences, gives these performances an additional soul and sensibility in counterpoint to the rigorous demands of studio recordings. Particular care was taken when restoring the sound of these tapes in order to meet CD standards while preserving the original colours of the period.

Patrick FRÉMEAUX & Gilles PÉTAR

CD1 : GILLESPIANA SUITE: PRELUDE • GILLESPIANA SUITE: BLUES • GILLESPIANA SUITE: PANAMERICANA • GILLESPIANA SUITE: AFRICANA • GILLESPIANA SUITE: TOCCATA • CARAVAN • CRIPPLE CRAPPLE CRUTCH

CD2 : INTRODUCTION BY NORMAN GRANZ • DIZZY’S INTRO • DESAFINADO • LORRAINE • LONG LONG SUMMER • PAU DE ARARA • CRIPPLE CRAPPLE CRUTCH • KUSH

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE ET DISCOGRAPHIE : GILLES PÉTARD ET MICHEL BRILLIÉ, LIVRET : MICHEL BRILLIÉ

NEW YORK - CHICAGO 1940 - 1947

ROCK JAZZ & CALYPSO 1920 - 1962

LIVE IN PARIS - 21 MARS / 11 OCTOBRE 1960

Live in Paris – 1960-1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Gillespiana Suite: PreludeDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:05:021960

-

2Gillespiana Suite: BluesDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:10:551960

-

3Gillespiana Suite: PanamericanaDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:06:251960

-

4Gillespiana Suite: AfricanaDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:06:361960

-

5Gillespiana Suite: ToccataDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:13:401960

-

6CaravanDizzy GillespieDuke Ellington00:09:281960

-

7Cripple Crapple CrutchDizzy GillespieDizzy Gillespie00:00:371960

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Introduction by Norman GranzDizzy GillespieNorman Granz00:01:121961

-

2'Dizzy''s Intro'Dizzy GillespieDizzy Gillespie00:01:391961

-

3DesafinadoDizzy GillespieNewton Mendoca00:03:581961

-

4LorraineDizzy GillespieDizzy Gillespie00:03:381961

-

5Long Long SummerDizzy GillespieLalo Schifrin00:08:441961

-

6Pau de AraraDizzy GillespieGuio De Morais00:08:581961

-

7Cripple Crapple CrutchDizzy GillespieDizzy Gillespie00:01:161961

-

8KushDizzy GillespieDizzy Gillespie00:20:351961

Dizzy Gillespie (feat Lalo Schifrin)

Live in Paris 1960-1961

Par Michel Brillié

The Messenger of Africa

“We were the first in the United States to play that music, samba, in the context of jazz. We had a lot of samba music and Stan Getz used to bug me to death trying to get some of these tunes…”

Well there it is. Dizzy was the forerunner for the Bossa Nova craze that swept the United States and the world in 1962. This is no wonder for a man who spent his life as a musician looking for all the tracks that brought him back to his roots, to Africa.

As early as 1937, John Birks Gillespie, then a not-so-shy teenager, had discovered with Cuban flutist Alberto Soccaras clave, the basic rhythmic pattern of Afro-Cuban music.

Some time later, Mario Bauza, who was with Gillespie part of the trumpet line-up in Cab Calloway’s Orchestra, took him under his wing and introduced him further to the tempos of the Isle. Bauza was “like my father” wrote Diz; Bauza’s stepbrother was Machito, the illustrious band leader and percussionist of that generation. Dizzy was convinced that when he would get his own band together, he had to have a conga player. Period.

Pozo El Conguero

Ten years went by. After the war, in 1947, Dizzy had formed his big band, with which he attempted to combine jazz and Latin tempo. With Kenny Clarke on drums, Gillespie wanted to add a touch of Cuban percussion.

Mario Bauza: “Well, I was the cause of it, that marriage, that integration. When Dizzy left Calloway, he told me he wanna do something. I said, ‘Well, why don’t you get on this kick?’ We had this idea for a long time. We talked together in the band about it.

So he said, ‘You got the man?’

‘I got the man for you to do that gig.’ So I got a hold of Chano Pozo.”

The great Cuban conguero would set the standards for modern Afro-Cuban Jazz. Even if both men had a very hard time trying to communicate, since Pozo did not speak English, nor did the trumpet player speak Spanish. How did they do it then? Diz wrote, ‘Chano would answer, ‘Deehee no peek pani, me no peek Angli, bo peek African.’

Dizzy was the great shepherd who wanted to bring together all the sheep of jazz and root music.

“It’s strange how the white people tried to keep us separate from the Africans and from our heritage. That’s why, today, you don’t hear in our music, as much as you do in other parts of the world, African heritage, because they took our drum away from us. If you go to Brazil, to Bahia, you find a lot of African in their music; you go to Cuba, you find they retained their heritage; in the West Indies, you find a lot. In fact, I went to Kenya and heard these cats play and I said, ‘You guys sound like you’re playing calypso from the West Indies.’

A guy laughed and he said to me, “Don’t forget, we were first!”

The trumpet player went on a crusade looking for The Rhythm: “The people of the calypso, the samba have all something in common from the mother of their music. Rhythm. The basic rhythm because Mama Rhythm is Africa.”

Going back to Pozo, here was a peculiar individual. He was a tough guy straight out of the Cuban Streets, a petty criminal, - and a dancer, a percussionist – who emigrated to the U.S. in ’47 to escape the racism that prevailed in Cuban musicians circles. With Pozo and his conga now a part of Gillespie’s band, the Cuban wrote him the anthem of Cubano-Bop fusion: “Manteca” the quintessence of Afro-Cuban Jazz. “Manteca” is Cuban slang for heroin. Drugs were indeed the cause of Pozo’s death. In December 1948, he was shot by a bookie in a Harlem bar.

Beret…and baguette

In fall of 1947, following an historical concert at Carnegie Hall, Dizzy’s brand-new big band including Pozo embarked on an European tour. It was not a first for Gillespie. In 1937, the twenty-year-old trumpet player of Teddy Hill’s Orchestra had already come to Europe with the prestigious Cotton Club Revue. During Paris World’s Fair, the show was on for six weeks at the Moulin Rouge, along with Josephine Baker and a score of dancers. There, the French had become acquainted with the Lindy Hop, the dance that became rock and roll. For his part, Dizzy took advantage of his spare time to explore the neighboring streets of Pigalle, and develop his taste for young women, with a special interest for blondes. And he also found one of the mythical accessories of Beboppers: the beret.

And so, a decade later, he returned to the French capital wearing the archetypical French headgear, only this time as a true Big Name Star. But, on top of the beret – so to speak – he had the baguette… I mean, the “baton” of chef.

Meanwhile, Paris was burning hot. Pozo was an imposing man. His conga drums, which he made himself by burning sections of tree trunks and covering them with goatskin, had to be heated up with Sterno before each gig. So Chano was particularly noticed by the French audience. The Salle Pleyel concerts were a founding event for the French consciousness: “I think most of today’s French jazz musicians who were at the concert discovered their vocation for jazz then and there, and particularly for bebop.”

For Boris Vian, “Young American musicians copy everything about Dizzy, the beret, the goatee... But they cannot copy the consistency of his attack, his confidence all over the trumpet, his infallible harmonic instincts, and the purity of his dry, clean sound.”

These concerts were still vivid in France when Dizzy returned to Paris in March 1952. This time he has come for a substantial recording session sided by French and American musicians. On one side, jazzmen such as René Vasseur, Jean Jacques Tilchet ; on the other, Don Byas or Art Simmons. For the occasion, the posh Theâtre des Champs Elysées has been turned into a recording studio. Gillespie enjoyed it and tried some musical experiences during this transition period between bebop and the tighter hard bop groups of the later part of the fifties. Almost a year after that, he played again at the Salle Pleyel on February 9, 1953, and then, at the end of the same month, he had another recording session in the Parisian “Magellan” studio. There, he performed amidst a string orchestra led by Michel Legrand, and taped a variety of different numbers such as “Stormy Weather” or “Jealousy”.

Yes Dizzy Digs Paris…And he did indeed visit the city on a constant basis, as a member of the Jazz at the Philharmonic Tours of Norman Granz, such as the one in 1958.

And he enjoyed travelling… The young man that sailed across the Atlantic on the Ile de France ocean liner in the mid-thirties turned into a true ambassador for jazz - and for the U.S.A.- all over the world. This passion kept on up to the creation of Gillespie’s United Nations Orchestra, a eclectic set of some of to best jazz musicians with up-and-coming young players.

Diz the globetrotter

As soon as 1956, the Messenger set to work. The idea came from a Harlem politician, Adam Clayton Powell. He believed that sending Dizzy with a big band around the world would promote a positive image of the United States. To ensure this request from the Department of State, which funded the tours, the band had to be multiracial. So Quincy Jones, whom Dizzy asked for a hand, recruited several white musicians, including Phil Woods. The band had to be male and female; Jones asked a recent West Coast friend, Melba Liston, to join the trombone section of the band. The State Dept. Big Band went to Iran, then on to Pakistan, Lebanon, Turkey and finally Greece. On several occasions, Dizzy broke down the barriers and gave away free tickets to underprivileged youngsters milling around the concert halls, unable to afford the entry cost. “We’re here to play for the people” he told embassy officials. In Greece, he was carried shoulder high through the streets by cheering crowds.

The second international tour of late ’56 was even more memorable to Dizzy. This time it was in South America where he had to speak the good word: in Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. There the musician encountered a firsthand experience with the subtle and elegant rhythms of samba and tango.

But the most important contribution of this South American tour was the meeting between Dizzy and a young Argentinean pianist, composer and arranger, Lalo Schifrin.

Schifrin had just spent four years in Paris studying at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris under Olivier Messiaen. In his spare time, he also was a jazz piano player appearing at the Club Saint Germain, or an avid movie buff at the Cinémathèque. At the end of ’56, he went home to Buenos Aires to get back to his family. And this was where he met with Dizzy.

“Dizzy was my idol! I was a student of his music. I knew all of the compositions. I knew all the solos by memory from the records. I had just brought together my own band – Gato Barbieri was part of it – and we played for him. “Did you write these charts?” I said, yes. Dizzy then offered me to come to the United States as an arranger-pianist. I didn’t believe it, you know. I didn’t think he meant it. He said, “When you come over there, look me up.”

It took two years to Lalo to overcome the various administrative hassles of the times. Once in New-York, he was unable to get in touch with Dizzy, who had left for an extensive tour. Lalo reformed a trio and played at Basin Street East; he also stood in for various unavailable jazzmen, Peterson, Garner, Hank Jones…This went on for a couple of years, and then Lalo Schifrin finally got through to Diz. The moment Lalo came, “Dizzy said, ‘Yeah, where you been?’ Then he asked me to write something and bring it over after the weekend.

On Monday, he sent a car and I got there. I played what I had composed and arranged. He asked me some more details about this Suite. I told him it was a piece for a quintet with an added brass formation: four trumpets, four horns and a tuba. Just brass, no saxes, but, in addition, Latin American percussion.

“How much time do you need to write all this?” he asked me. I said, “three weeks”. So he picked up the phone and called Norman Granz. “Norman, I need a studio in one month.” I was speechless.”

Lalo and the master

The “Gillespiana” Suite was recorded in New-York from November 14 to 16, 1960. Schifrin took over from Junior Mance, who had left Dizzy’s group. A large studio band supported Gillespie’s sextet, that included Leo Wright, Art Davis, Chuck Lamplin, and Candido Camero on congas. Barely ten days later, on the stage of the Salle Pleyel in Paris, the French public discovered the entire work for the first time. The first American live rendition was the following year, on March 4, 1961, at New-York’s Carnegie Hall.

In a way, “Gillespiana” was to Dizzy a mean to access some kind of respectability. “I’ve struggled to establish jazz as concert music, not just music you hear in clubs or places where they serve whiskey” he wrote in his autobiography. He must have found in Schifrin a talent to help him achieve that goal. Schifrin allowed Gillespie to go further, instead of remaining a nostalgic symbol of past jazz. Gillespie acknowledged this driving force in the Argentinean to modernize his work while keeping his Latin tradition, which had been his mark ever since the forties with Chano Pozo and “Manteca”. Because of Schifrin’s classical training, Gillespie likened his relationship with him to that between Duke Ellington and arranger and composer Billy Strayhorn.

This five movement suite in form of a Concerto Grosso was a significant achievement with the public and sold a million copies, one of the biggest successes for the trumpeter.

As for Schifrin, he was a man fulfilled in all respects. He was playing with a master, a friend, and a world-known jazz personality who brought light to his work. And he was, at least for a while, out of the daily grind of film scoring in Argentina, playing jazz instead.

Dizzy-finado

Autumn 1961, September 23. Dizzy’s quintet appeared at the Monterey Festival. For this performance, Gillespie’s theme was a “musical safari”.

He outlined his concept in the concert’s intro:

“As you would see in the program we are doing an alleged musical safari…This alludes to the different music that has come from Africa into the different countries...First we’d like to play a number that we stole in Brazil…and this one is titled “Dizzy…finado.”

“Desafinado”, Tom Jobim’s ultimate bossa nova standard, would be taken from Gillespie by Stan Getz a few months later, and become as part of Getz’s Jazz Samba album a huge hit around the world.

In the meantime, a couple of months later, the DizGang were back on the road. From November 11 to December 2, Norman Granz’s JATP was in Europe, Dizzy sharing the bill with John Coltrane. It was an almost unending stream of thirty gigs in less than three weeks, with one or two concerts per day in Germany, England, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Finland and France. In Paris, on November 18, they performed at the Olympia Theater.

The man was indeed “back home again”, feeling very comfy. He chided some latecomers with the few French words he has picked up “Sit down! You okay?”

Since Monterey, the musician has refined his intro:

“This evening we’re going to play what we call a musical safari…This alludes to the fact of the importance of African music has...For the western hemisphere…We’d like to take you on a musical tour to Southern Brazil…Northern Brazil...West Indies… Cuba…but not by airplane...Take you to Mississippi…but not by bus…”

Dizzy was referring to two significant events of 1961: in April, the Bay of Pigs crisis, a failed invasion of Cuba by the C.I.A., and in May, the bus crusades of the Freedom Riders, a series of political protests against segregation by blacks and whites who rode buses together through the American South . In Mississippi, the subsequent repression was the most violent, with brutal arrests and imprisonments.

Once again, this time at the Olympia Theater, Dizzy took every opportunity to show his political and humanitarian involvement. It could be done in a humorous way, by trying to desegregate a pool in Kansas City wearing an outrageous outfit. Or, more “seriously”, when he campaigned in 1963/64 for the United States presidency. Dizzy organized meetings-cum-concerts to spread his progressive word. He had put together a hard hitting program: lower taxes, reduction of weapons, free education and health care, equal opportunity law, disbandment of the Ku Klux Klan, ending of the Vietnam War… (See box)

In the service of humanity

Some years later, Dizzy converted to the Baha’i faith, a monotheistic religion initially developed in Iran in the 19th century. It professed unity of God, unity of religions, unity of mankind. For Gillespie, this basic element of the Baha’i faith had a musical homeland in Brazil. For Dizzy, music in this country was the symbol of “unity with diversity.”

One faith, one country, and one musician to fulfill the part:

“There is a parallel with jazz and religion. In jazz, a messenger comes to the music and spreads his influence to a certain point, and then another comes and takes you further. In religion, God picks certain individuals from this world to lead mankind up to a certain point of spiritual development. Other leaders come.”

Dizzy, the giver?

From Big Band to Be-bop to Afro-Cuban, up to his merging of music from Brazil and the West Indies... With his worldwide tours, with the United Nations Orchestra, Dizzy never ceased to show his commitment to the fundamentals of unity, peace and brotherhood.

In the final page of To Be or not to Bop, he defined his wish for a higher role: “That’s the way I would like to be remembered, as a humanitarian.”

A small personal addendum

It was in early 1961, around 11:00 PM. I was a fifteen-year-old teenager listening on a small Hitachi transistor radio to the jazz show “Pour Ceux Qui Aiment le Jazz” for the first time. I had just met Daniel F., and he had somehow advised me to get into jazz… Out of the kilocycles arose the final bars of “Blues” from Gillespiana, when Leo Wright’s flute and Dizzy’s trumpet play in unison. More than sixty years later, it stills echoes.

Michel Brillié

© Frémeaux & Associés 2023

Excerpts from Dizzy Gillespie’s speech for Presidency

“When I’m elected President of the U.S.A., my first executive order will be to change the name of the White House to the “Blues” House.

Income tax must be abolished, and we plan to legalize ‘numbers’…/…

The Army and Navy will be combined so no promoter can take too big a cut off the top.

The National Labor Relations Board will rule that people applying for jobs have to wear sheets over their heads so bosses won’t know what they are until after they’ve been hired.

My Cabinet

Miles Davis, Head of C.I.A.

Max Roach, Minister of War

Charlie Mingus, Minister of Peace

Duke Ellington, Minister of State

Malcom X, United States Attorney General

Louis Armstrong, Minister of Agriculture

Peggy Lee, Ministress of Labor

Ella Fitzgerald, Secretary for Health, Education & Welfare

As a vice-president, I would like Ramona Crowell, a leader of the John Birks Society and a registered Sioux Indian.”

1. Unless otherwise stated, all verbatim quotes from people mentioned here are taken from Dizzy’s autobiography: To Be or not to Bop, Dizzy Gillespie with Al Fraser, Doubleday Books, 1979

2. Untranslatable joke on:

- Baguette, the French bread, part of the image of the stereotypical French man, with his black beret and

- Baguette, in French, also the baton of the leader of an orchestra.

Couldn’t resist it…

3. Maurice Cullaz, in Groovin’ High, the Life of Dizzy Gillespie, Alyn Shipton, Oxford University Press, 1999

4. Boris Vian, Combat, 1948, in Groovin’ High,op. cit.

5. Cf Jazz at the Philharmonic 1958-1960, 3CD BoxSet Frémeaux & Associés, 2016

6. Jean-Michel Reisser, Lalo Schifrin, Entretien avec le compositeur, Cosmopolis , April 12, 2007

CD1

1 Gillespiana Suite: Prelude (Lalo Schifrin) 05’02

2 Gillespiana Suite: Blues (Lalo Schifrin) 10’55

3 Gillespiana Suite: Panamericana (Lalo Schifrin) 06’25

4 Gillespiana Suite: Africana (Lalo Schifrin) 06’56

5 Gillespiana Suite: Toccata (Lalo Schifrin) 13’40

6 Caravan (Duke Ellington - Juan Tizol) 09’28

7 Cripple Crapple Crutch (Dizzy Gillespie / Pleasant Joseph) 0’37

Total time 53:03

Recording Date

November 25,1960

Recording Place

Salle Pleyel, Paris, France

Produced by: Daniel Filipacchi, Norman Granz & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Candido Camero Congas on tracks 6 & 7

Art Davis Bass

Dizzy Gillespie Trumpet

Chuck Lampkin Drums

Lalo Schifrin Piano

Leo Wright Alto Saxophone, Flute

CD2

1 Introduction by Norman Granz (Norman Granz) 01’12

2 Dizzy’s Intro (Dizzy Gillespie) 01’39

3 Desafinado (Newton Mendoça - Antonio Carlos Jobim) 03’58

4 Lorraine (Dizzy Gillespie) 03’38

5 Long Long Summer (Lalo Schifrin) 08’44

6 Pau De Arara (Luiz Gonzaga - Guio de Morais / Luiz Gonzaga - Guio de Morais -

Lalo Schifrin) 08’58

7 Cripple Crapple Crutch (Dizzy Gillespie / Pleasant Joseph) 01’16

8 Kush (Dizzy Gillespie) 20’35

Total time 50:00

Recording Date

November 18,1961

Recording Place

Olympia Theater, Paris, France

Produced by: Daniel Filipacchi, Norman Granz & Frank Ténot

Personnel

Bob Cunnigham Bass

Dizzy Gillespie Trumpet

Mel Lewis Drums

Lalo Schifrin Piano

Leo Wright Alto Saxophone, Flute

Dedicated to Claude Boquet, Bill Dubois, Jean Claude, Philippe Moch,

Raymond Treillet and the gang

La collection Live in Paris :

Collection créée par Gilles Pétard pour Body & Soul et licenciée à Frémeaux & Associés.

Direction artistique et discographie : Michel Brillié, Gilles Pétard.

Coordination : Augustin Bondoux.

Conception : Patrick Frémeaux, Claude Colombini.

Fabrication et distribution : Frémeaux & Associés.