- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

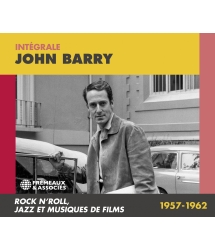

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

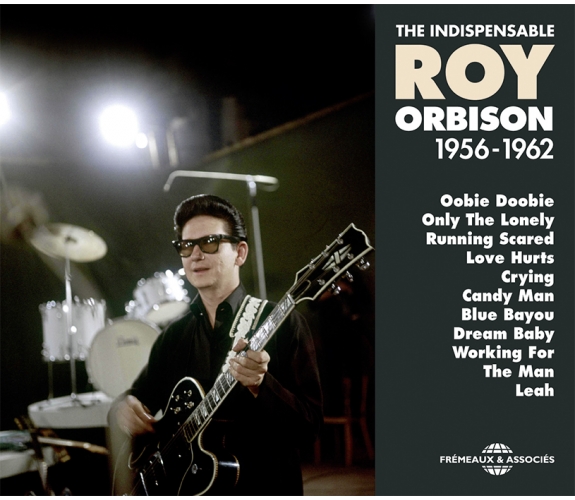

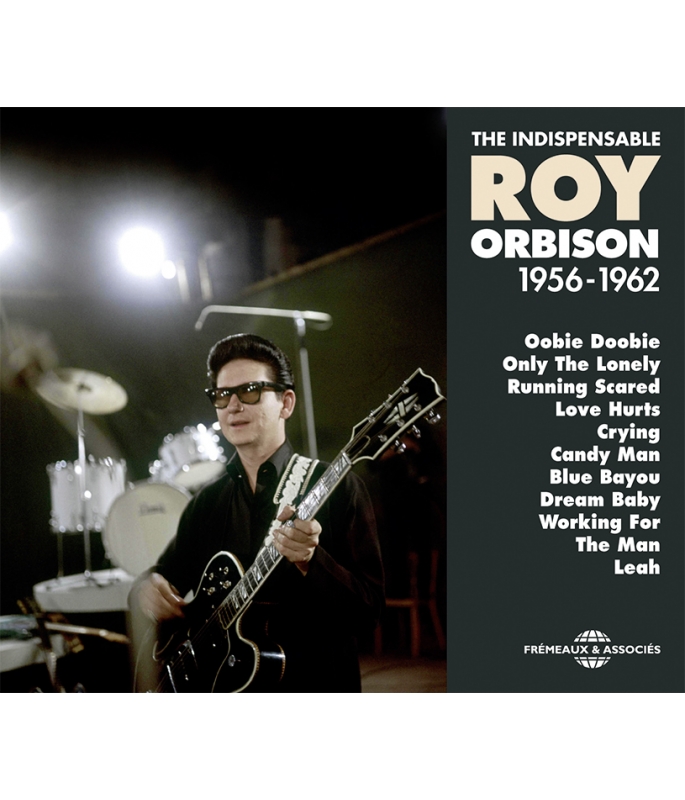

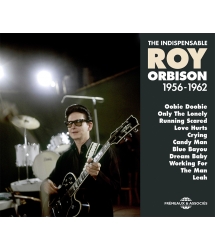

THE INDISPENSABLE 1956-1962

ROY ORBISON

Ref.: FA5438

EAN : 3561302543826

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 1 hours 49 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

THE INDISPENSABLE 1956-1962

THE INDISPENSABLE 1956-1962

After a rockabilly outset where his melodies and lyrics already showed ambition, Roy Orbison invented a new, sophisticated form of rock which had refined, elegant arrangements. A friend and inspirer of The Beatles as well as Elvis Presley, he was one of the great precursors of the 1960s’ creative explosion, one of the first to give rock a lavish orchestral colour. An extraordinary singer, his romantic, deeply original work still symbolizes the opulent and progressive America of the Kennedy era. With a detailed 28-page booklet by Bruno Blum, this album tells the story of the great Roy Orbison. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

ELVIS PRESLEY, BILL HALEY, ROY ORBISON, GENE...

THE INDISPENSABLE 1954-1961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Ooby DoobyRoy OrbisonAllen Richard Penner00:02:141956

-

2Go! Go! Go! (Movin' on Down The Line)Roy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:101956

-

3Tryin' To Get To YouRoy OrbisonRose Marie McCoy00:02:431956

-

4You're My BabyRoy OrbisonJonnhy Cash00:02:081956

-

5RockhouseRoy OrbisonHarold Jenkins00:02:051956

-

6DominoRoy OrbisonHarold Jenkins00:02:181956

-

7Sweet And Easy To LoveRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:141956

-

8Devil DollRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:121956

-

9The Cause Of It AllRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:271956

-

10Chicken HeartedRoy OrbisonBill Justis00:02:171957

-

11I Like LoveRoy OrbisonJ.H. Clement00:02:331957

-

12Foll's All Of FameRoy OrbisonJerry Freeman00:02:291957

-

13A True Love GoodbyeRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:211957

-

14A Mean Little MamaRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:01:591957

-

15Problem ChildRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:221957

-

16You're Gonna CryRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:081957

-

17This Kind Of LoveRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:101957

-

18It's Too LateRoy OrbisonHarold Willis00:02:011957

-

19I Never KnewRoy OrbisonSam Phillips00:02:231957

-

20LoverstruckRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:01:261958

-

21One More TimeRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:01:181958

-

22I Was A FoolRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:181958

-

23With The BugRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:291959

-

24Paper BoyRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:111959

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1UptownRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:071959

-

2Pretty OneRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:191959

-

3Only The LonelyRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:271960

-

4Here Comes That Song AgainRoy OrbisonDick Flood00:02:451960

-

5Blue AngelRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:451960

-

6Today's TeardropsRoy OrbisonEugene Francis Alan Pitney00:02:141960

-

7I'M Hurtin'Roy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:481960

-

8I Can't Stop Loving YouRoy OrbisonDon Gibson00:02:451960

-

9Running ScaredRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:121961

-

10Love HurtsRoy OrbisonBoudleaux Bryant00:02:281961

-

11Summer SongRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:461960

-

12LanaRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:191961

-

13CryingRoy OrbisonJoe Melson00:02:471961

-

14Candy ManRoy OrbisonBeverly Ross00:02:451961

-

15Let The Good Time RollRoy OrbisonBeverly Ross00:02:321961

-

16Blue BayouRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:311961

-

17Dream BabyRoy OrbisonCindy Walker00:02:341962

-

18The ActressRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:391962

-

19The CrowdRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:241962

-

20MamaRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:03:011962

-

21Working For The ManRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:281962

-

22LeahRoy OrbisonRoy Orbison00:02:401962

Roy Orbison FA5438

Roy Orbison

THE INDISPENSABLE

1956-1962

Roy Orbison

The Indispensable 1956-1962

Par Bruno Blum

Il a une des meilleures voix de tous les temps dans la musique populaire.

— Son producteur Jeff Lynne (Electric Light Orchestra)1

Redécouvert en 1987 quand David Lynch utilisa son « In Dreams » dans la bande son du chef-d’œuvre déjanté « Blue Velvet », Roy Orbison (23 avril 1936 - 6 dé-cem-bre 1988) a brusquement été accueilli dans le prestigieux gotha du Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Il apparut ensuite dans un fameux concert filmé où il fut accompagné par de célèbres admirateurs : Tom Waits, James Burton, Jackson Browne, T-Bone Burnett, Bonnie Raitt, k.d. Lang, Jennifer Warnes, Elvis Costello et Bruce Springsteen ! Contre toute attente, Orbison commença peu après à enregistrer un nouvel album, Mystery Girl, et fonda un nouveau groupe vocal avec rien moins que les chanteurs Jeff Lynne (Electric Light Orchestra), Tom Petty (Heartbreakers), son vieil ami l’ex Beatles George Harrison — et Bob Dylan en personne. Les Traveling Wilburys ont ainsi enregistré deux albums qui connurent un énorme succès. Roy Orbison était soudain assailli de propositions de concerts. Au cours de cet inimaginable retour qu’il n’espérait plus après vingt ans d’échecs et de drames personnels, c’est avec le concours de Bono (U2), Elvis Costello et Jeff Lynne qu’il termina son nouvel album solo. Un nouveau succès international dont le single « You Got It » monta au n°9 aux États-Unis. Tragiquement, fin 1988 Roy Orbison décéda d’une crise cardiaque due à sa tabagie (il avait subi un triple pontage en 1977), quelques jours seulement avant la sortie de l’album, avant son succès magistral à venir — et avant de toucher les droits d’auteur des Traveling Wilburys. Il avait 52 ans. Cinq jours avant sa disparition, le sort a voulu que je fusse le dernier à interviewer cette légende du rock américain. Il me confia ce soir-là dans les bureaux des disques Virgin :

« Il faut avoir confiance, c’est tout. Dans mes voyages je rencontre plein de gens qui me demandent des conseils et je leur réponds « Ne laisse pas tomber. Même si tu le fais juste pour toi-même. Je sais que dans ma propre carrière… si je m’étais arrêté ne serait-ce qu’une semaine trop tôt… Certaines chosent arrivent. Avant certains événements. Si j’avais dit que je ne tournerais pas juste avant la tournée avec les Beatles, ou la tournée avec les Stones, la tournée avec les Beach Boys… ou si je n’avais pas été à Nashville rencontrer ce type qui n’avait encore jamais fait de disques de sa vie… il faisait de la promo pour Mercury. Il avait décidé de se lancer dans le disque, il a emprunté de l’argent et il a obtenu de Chet Atkins qu’il l’aide à faire mon disque. Qui est monté au numéro un. Alors il faut juste continuer et avoir confiance en soi. »2

The Wink Westerners

Roy Kelton Orbison (23 avril 1936-6 décembre 1988) est né à Vernon, au nord du Texas à deux heures de Dallas. Cette petite ville à la frontière de l’Oklahoma était sur le Chisholm trail, la piste empruntée par les cow-boys qui accompagnaient les bovins du Texas au Kansas. Souffrant du chômage pendant la période de la Grande Dépression, à la recherche de travail Nadine Schultz, Orbie Lee Orbison et leurs enfants s’installèrent à Fort Worth (Texas) avant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Roy y fréquenta l’école élémentaire de Denver Avenue mais une épidémie de polio incita la famille à rentrer à Vernon. Ils partirent ensuite à Wink (Texas), une petite ville ennuyeuse que Roy rêvait de quitter. Comme son futur ami Elvis Presley, qui deviendra l’un de ses grands admirateurs, et comme tous les enfants bien élevés du sud des États-Unis, Roy était effacé et d’une politesse exemplaire3. Il était aussi mal dans sa peau et, affligé par une mauvaise vue comme tous les Orbison, ne quittait jamais ses lunettes aux verres épais. Il reçut une guitare pour ses six ans.

Orbie le père de Roy était un mécanicien qui décida de s’investir dans l’industrie du pétrole et parvint progressivement à s’en sortir en devenant technicien d’un puits de forage. Il jouait de la guitare country (« surtout des chansons de Jimmie Rodgers ») et ensei-gna quelques accords à son fils. L’enfant s’est vite passionné pour la musique. Peu sûr de lui, il pensait que sa seule chance de réussir quelque chose était de travailler la guitare. Son oncle jouait du blues et lui a transmis ce qu’il pouvait. Mais Roy préférait le style country de son père. La première chanson qu’il a maîtrisée était « You Are my Sunshine », une reprise d’Oliver Hood rendue célèbre par Jimmy Davis, un chanteur de country qui devint par la suite gouverneur de Louisiane et fit de ce morceau l’hymne de son état.

Le petit Roy Orbison admirait les chanteurs de country Bob Wills et Ernest Tubb, qu’il vit à Fort Worth faire de la publicité pour une marque de lait, debout à l’arrière d’un camion. Il reçut sa première guitare à six ans et prit l’habitude de chanter avec ses oncles et cousins musiciens professionnels. Il n’avait que huit ans à la fin de la guerre quand il a commencé à participer à des émissions de radio où il chantait des reprises de country en direct, ainsi que « Joli Blon », un titre de zydeco. Il appréciait aussi les chanteurs de blues et la musique tex-mex mais il avait une passion pour les vedettes de la country Lefty Frizzell et Hank Williams. À dix ans il chanta dans un spectacle de camelot, un « medicine show » où l’on vendait un élixir de santé. Il se tailla bientôt un succès à l’école en interprétant le « Mountain Dew » de Grandpa Jones et devint l’animateur de sa propre émission de radio sur KERB à Kermit vers l’âge de treize ans.

Il n’aimait pas sa couleur de cheveux très claire et a commencé à se teindre les cheveux en noir. Il con-tinuera à le faire toute sa vie. Devenu étudiant à Wink (Texas), Roy Orbison a formé en 1954 les Wink Westerners, qui reprenaient des compositions de Frizzell et Hank Williams. Il a puisé ses musiciens dans le groupe du lycée de Wink, parmi lesquels un mandoliniste amplifié. Roy s’accompagnait et jouait différents succès de l’époque, dont « In the Mood », « Moonlight in Vermont » et des compositions country de Webb Pierce. Ils ont joué dans les bars honky-tonk (de modestes saloons), des bals et des fêtes diverses dans la région, notamment à la soirée de soutien au directeur de son lycée dans sa campagne pour la présidence du Lion’s Club du district. Quand on lui a proposé 400 dollars pour un concert, Roy a réalisé qu’il pourrait s’orienter vers une carrière de musicien professionnel. Il a néanmoins rejoint le North Texas State College où il envisageait de se spécialiser dans la géologie au cas où la musique ne serait pas rentable. Le moins qu’on puisse dire est qu’il avait un niveau d’études relativement élevé si on le compare avec celui des autres vedettes du rock des années 1950. Mais ses notes étaient de plus en plus mauvaises et à la fin de l’année scolaire 1954-1955 il envisageait de laisser tomber la géologie pour s’orienter vers une carrière d’enseignant.

The Teen Kings

Quand il a entendu le premier disque d’Elvis, une reprise de « That’s All Right », un blues rapide d’Arthur Crudup, Roy n’a « pas compris » où Elvis voulait en venir. Un Blanc interprétant du rock, musique noire par excellence, c’était surprenant. La face B, «Blue Moon of Kentucky», une reprise d’un bluegrass archi-blanc de Bill Monroe, l’a rassuré. Il résidait à Odessa (Texas) en 1955 quand, étudiant à la North Texas State University de Denton, il découvrit Elvis Presley sur scène à la ville voisine de Dallas. L’hystérie collective qui entourait tous les déplacements de l’idole avait commencé. Très marqué par le chanteur débutant qu’il enviait, il forma un autre groupe, le nomma les Teen Kings et obtint une apparition dans un programme télévisé de la chaîne KMID à Midland (Texas) vers septembre 1955. C’est Cecil « Pop » Holifield, un contributeur du magazine Billboard et dirigeant d’un magasin de disques à Midland et un autre à Odessa, qui a arrangé cette pres-tation. Pop s’occupait aussi d’organiser des concerts pour les artistes Sun Johnny Cash et Elvis Presley ; il invita Cash à cette même émission. C’est ainsi que Johnny Cash a rencontré et écouté Roy Orbison, l’a invité à un de ses concerts le12 octobre 1955 au lycée de Midland et lui a présenté Elvis Presley, alors vedette montante, en tête d’affiche de la soirée. Elvis et Johnny Cash ont alors essayé de convaincre leur producteur chez Sun d’auditionner Roy Orbison, mais sans succès.

Bobbie Jean Oliver, une chanteuse et accordéoniste qui se produisait souvent avec Roy et les Teen Kings et sortait avec un de ses membres (James Morrow), a convaincu ses parents de financer un enregistrement du groupe. C’est au studio de Norman Petty à Clovis (Nouveau-Mexique) qu’ils enregistrèrent le 4 mars 1956 leur premier 45 tours Ooby Dooby, une chanson composée par deux camarades d’université. Trying to Get to You figurait en face B4. Le disque a été publié sous l’étiquette Je-Wel, créée pour l’occasion par Chester Oliver (le père de Jean Oliver) et le chanteur Weldon Rogers (ex-mari de la même Jean). Il reste une pièce de collection introuvable : la bande a disparu du studio de Petty en 1984 et les enregistrements n’ont pas été réédités. Le jour de sa sortie, Orbison a offert un exemplaire du disque de démonstration à Pop Holifield, qui a appelé le studio Sun pour raconter à Sam Phillips que le disque se vendait bien. À son insistance pour qu’il auditionne Roy Orbison et ses Teen Kings, Phillips a rappelé quelques jours plus tard pour qu’ils viennent directement enregistrer chez lui à Memphis, mais sans audition. Le père de Roy a dû co-signer le contrat Sun : son fils n’était pas encore majeur. Signé par un mineur, le contrat avec Je-Wel n’était donc pas valable et Sun a placé une injonction afin que le premier disque des Teen Kings soit retiré de la vente — et ce malgré un pressage de plusieurs milliers d’exemplaires réalisé en lien avec Norman Petty (alors manager et éditeur peu scrupuleux de Buddy Holly), ce qui coûta cher au papa de Jean Oliver. Le disque originel disparut alors de la circulation.

Sun Records

Sun avait lancé Elvis Presley un an plus tôt et la concurrence faisait rage au printemps 1956 chez les rockers blancs. En pleine ségrégation raciale, le brillant producteur Sam Phillips cherchait d’autres interprètes blancs capables de chanter dans un style proche du rock afro-américain auquel il donnait une couleur plus country. Et la formule fonctionnait. Les légendaires séances d’enregistrement au petit studio Sun venaient de donner naissance à la déferlante rockabilly : elles avaient déjà fait connaître Elvis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins et bientôt Jerry Lee Lewis. Phillips avait véritablement ouvert le marché du rock au grand public blanc.

Moins populaire que ses pairs, Roy Orbison n’en reste donc pas moins le cinquième sur la liste des grands classiques du rock chez Sun5. Il avait vingt ans et emménagea à Memphis chez Sam Phillips avec sa petite amie Claudette Frady, qui n’avait que seize ans et faisait chambre à part. Fin mars 1956, il ré-enregistra Ooby Dooby (alors qu’il en avait déjà assez de cette chanson) et Go! Go! Go! (Movin’ on Down the Line) bientôt repris par Jerry Lee Lewis. Ces deux nouvelles versions ouvrent cet album.

« Quand on enregistrait Ooby Dooby, Sam Phillips m’a apporté une pile de gros 78 tours et a dit « Bon je veux que tu chantes comme ça ». Il a passé « That’s All Right » d’Arthur Crudup. Je n’ai pas fait trop attention et il a dit « Chante comme ceci, comme cela… » et il a mis une chanson de Junior Parker, « Mystery Train ». Je n’arrivais pas à le croire. J’ai dit : « Écoute Sam, je veux chanter des ballades. Je suis un chanteur de ballades. » Et il a dit « Non, tu vas chanter ce que je veux que tu chantes. Tu t’en sors très bien ». Elvis voulait chanter comme les Ink Spots ou Bing Crosby. Sam avait fait la même chose avec lui. Et la même chose avec Carl Perkins ».

— Roy Orbison6

Roy Orbison et ses Teen Kings ont signé un contrat avec l’agent Bob Neal, ancien imprésario de Presley et propriétaire de l’agence Stars Incorporated. Ils se sont retrouvés en tournée à jouer dans des dance halls et des drive-ins entre les films. Ils étaient à la même affiche que Sonny James, Johnny Horton, Johnny Cash et plus tard Jerry Lee Lewis, Warren Smith et Carl Perkins l’auteur de l’hymne du rockabilly « Blue Suede Shoes », et d’autres artistes country et rockabilly encore. En pleine mode du rock, porté par le son Sun originel et une distribution confiée aux disques Chess au nord du pays, Ooby Dooby est monté jusqu’au numéro 59 des classements du Billboard et s’est vendu à 200 000 exemplaires. Imitant Elvis, Roy s’agitait sur scène en faisant de son mieux.

« On dansait et on remuait. On faisait tout ce qu’on pouvait pour avoir des applaudissements parce qu’on n’avait qu’un seul disque qui marchait, Ooby Dooby ».

— Roy Orbison

Mais concurrencé par des dizaines d’artistes qui enregistraient dans le style rockabilly en vogue, ses autres disques se sont mal vendus. Roy Orbison n’avait qu’un an de moins qu’Elvis Presley, qui appréciait beaucoup sa voix et avec qui il est véritablement devenu ami. Comme Elvis et Little Richard, Chuck Berry ou Gene Vincent, Orbison faisait partie de la deuxième génération de rockers, celle qui a fait découvrir ce style au public blanc après les rocks originels de Louis Jordan, Tiny Bradshaw ou Roy Brown et les fulgurances du country boogie7. Pourtant Orbison était bien à part. S’il appréciait le rock noir, il est toujours resté assez hermétique aux influences afro qui ont contribué au succès de ses copains de l’écurie Sun. Son rockabilly, en principe un hybride des deux cultures, est resté éloigné de l’influence du gospel noir et du blues qui ont tant marqué les premiers disques célèbres d’Elvis, Carl Perkins ou Gene Vincent8. Comme Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison s’inscrivait en droite ligne de l’héritage country. Timide, doux, sensible, fin et intelligent, le jeune homme n’était pas très beau. Affublé de grosses lunettes en permanence, il se teignait les cheveux secrètement, ne buvait pas et n’a jamais été à l’aise parmi ses bruyants collègues rockers.

J’aimerais être un mauvais garçon/Mais j’ai trop peur qu’on me fasse mal./J’ai un cœur de trouillard.

— Roy Orbison, Chicken Hearted, 1957.

Tandis que ses coreligionnaires du rock frimaient avec arrogance et affichaient leur virilité brute, le sensible Roy Orbison préférait chanter les tourments de l’amour à corps perdu. Vulnérable, complexé et travailleur, il soignait ses compositions (Jerry Lee Lewis et Elvis ne composaient pas eux-mêmes la plupart de leurs chansons), creusait les mélodies et exprimait ses déceptions et douleurs. Ses ballades étaient refusées par Sam Phillips, qui ne voulait que du rock au tempo rapide. Jack Clement, le producteur et découvreur de Jerry Lee Lewis chez Sun, lui a même dit qu’il ne réussirait jamais avec des ballades. Un comble quand on connaît sa future carrière.

Son producteur ne s’intéressait pas à son orientation musicale et à ses idées. Orbison estimait en outre que Sam Phillips, endetté malgré la vente du contrat d’Elvis Presley à RCA, n’était pas assez professionnel puisque « L’industrie l’avait dépassé du jour au lendemain et il ne s’en était même pas rendu compte ». Sa période Sun a tout de même donné quelques classiques dont Ooby Dooby, Rockhouse (enregistré plus tard par Bobby Fuller, les Stray Cats, etc.) et Go! Go! Go! (repris avec succès par Jerry Lewis sous le nom de « Down the Line » et « Movin’ on Down the Line »). Buddy Holly enregistra plusieurs de ses compositions : « You’ve Got Love », « A True Love Goodbye » et « An Empty Cup! ». Sans oublier « Claudette » (qu’il épousa en 1957), un grand succès interprété par les Everly Brothers. Les futurs droits d’auteur de ce disque, paru au printemps 1958, l’ont probablement rassuré. Il a alors versé un acompte pour une Cadillac et trouvé le courage de laisser tomber Sam Phillips. Sun était incapable de le suivre dans sa démarche artistique, qui rêvait d’orchestrations, de sophistication et de romantisme, des chansons qui feraient rêver la princesse qui sommeille en chaque jeune fille. Phillips n’a pas non plus compris son potentiel de compositeur. À vrai dire il appréciait surtout Roy Orbison pour sa maîtrise de la guitare électrique. Les chanteurs qui s’aventuraient à jouer en solistes étaient rares mais bosseur, Orbison avait un excellent niveau. Il est ironique que ses grands succès des années 1960 (disque 2) aient mis en avant sa voix exceptionnelle (encore mal maîtrisée en 1956) et qu’il n’ait joué de guitare sur aucun de ses titres les plus célèbres. Mais à ses débuts, ce sont ses parties de guitare électrique originales qui étaient remarquées.

J’ai appris à jouer de la guitare en essayant de copier les solos des premiers disques de Roy Orbison.

— Lou Reed9

RCA Victor

En 1957 Roy Orbison gagnait mal sa vie avec des tournées incessantes. Mais il ne trouvait pas assez d’engagements et incapable d’en payer les traites, il a dû rendre sa Cadillac. Il dépendait de sa famille et de ses amis pour vivre avec sa jeune épouse. En 1958 il a complètement arrêté la scène pendant sept mois et l’avenir lui semblait très noir. Cramponné à sa guitare dans son appartement minuscule, il continuait à composer des chansons et les proposait à la firme Acuff-Rose, un éditeur qui plaçait des compositions à des interprètes connus. Mais sans succès. En 1958 l’Amérique réactionnaire s’était mieux organisée pour résister aux influences afro-américaines incarnées par le phénomène Elvis Presley dans le rock. Un son plus blanc, plus country, incarné par Buddy Holly, les Everly Brothers et Elvis lui-même, était en demande. C’est à Nashville, situé comme Memphis dans le Tennessee, à la frontière du sud et du nord, que le centre de gravité du rock s’était déplacé. Roy essayait aussi de se placer comme interprète en proposant des chansons écrites par d’autres, qu’il enregistrait avec le géant de la guitare Chet Atkins10 — mais sans grand succès. Chet Atkins était un virtuose, adulé par Roy autant que par le guitariste attitré d’Elvis Presley, Scotty Moore. Célèbre, Atkins avait accepté de participer à des enregistrements d’Elvis pour RCA et avait des relations. Ils enregistrèrent notamment « Seems to Me », une composition de Boudleaux Bryant. Bryant décrira plus tard Roy Orbison comme un garçon timide, déçu et embrouillé par le métier du disque, qui chantait joliment, avec douceur et pudeur, comme s’il dérangeait. Mais RCA n’accepta que deux chansons et Roy vivait toujours dans le dénuement avec sa femme et son enfant en bas âge. Souvent en déplacement pour des concerts mal payés, il écrivait des chansons seul, réfugié dans sa voiture. Roy avait aussi rencontré Joe Melson, le chanteur du groupe de rockabilly les Cavaliers. Lui aussi originaire du nord du Texas, Melson avait grandi dans une ferme et se passionnait pour la musique. Ancré dans la tradition country et rockabilly comme Roy, il avait néanmoins commencé à écrire dans un style marqué par le rhythm and blues et possédait une ouverture d’esprit encline à la créativité. C’est d’abord chez lui à Midland (ouest Texas) qu’il a commencé à collaborer avec Roy Orbison. Les deux amis ont alors conçu quelques chansons aux mélodies plus ambitieuses que les rockabillys basiques de Roy, construits autour de structures de blues à trois accords 1-4-5 en douze mesures.

« Écrire avec un partenaire c’est vraiment bien quand tu arrives à un point où tu n’as plus rien qui vient. Tu… quand tes idées s’arrêtent quelqu’un prend le relais. Et même s’il n’apporte pas ce que tu veux, tu peux repartir de ça et dire « oui, c’est pas mal, mais j’ai encore mieux », et l’autre dit « non attends, j’ai quelque chose ». Ça marche comme ça.

— Et tu t’arrêtes quand ?

— (rires) En général tu t’arrêtes quand ça fait que tu te sens bien, et puis on est arrangeurs aussi et on sait quand un morceau a dit ce qu’il avait à dire. »

— Roy Orbison11

Monument Records

C’est alors que Wesley Rose, son agent, le dirigea vers Fred Foster, le jeune producteur et directeur des disques Monument. Né en Caroline du Nord le 26 juillet 1931, après le décès de son père Fred Luther Foster avait dû subvenir aux besoins de sa mère dans la ferme familiale. Robuste, ambitieux et indépendant, à dix-sept ans il est parti tenter sa chance à la capitale, Washington D.C. Il a ensuite travaillé chez ABC-Paramount et Mercury. Ces deux maisons de disques étaient orientées vers le grand public. Elles étaient capables de répondre à la demande des grosses radios et télévisions, de collaborer avec les plus grandes vedettes et de produire des enregistrements de grande qualité. Tout en continuant la promo pour Mercury, Foster devint distributeur de disques à Baltimore. Ainsi formé aux métiers du disque, en mars 1958 à vingt-sept ans l’intrépide et ambitieux jeune homme a investi toutes ses économies pour fonder les disques Monument et sa société d’éditions musicales, Combine Music. Sa marque a immédiatement décollé avec Billy Grammer (un grand guitariste de country), Billy Graves, Dick Flood (« The Three Bells »), Jerry Byrd (un guitariste de steel guitar country passionné par la musique hawaïen-ne) et Bob Moore (un grand bassiste de country, responsable du grand succès instrumental « Mexico » en 1961). Dès ses premiers succès, Fred Foster a racheté en 1959 les parts de son associé Buddy Deane, un disc jockey de la radio new-yorkaise WITH. Il s’est alors installé à Nashville, capitale de la country music où vivaient de grands musiciens — et où se développait le nouveau son américain dominant de cette époque. Dès son arrivée à Nashville en 1959 Foster encore débutant en matière de production a rencontré Roy Orbison, qui cherchait les moyens de réaliser ce qu’il entendait dans sa tête. Armé de ses idées originales, de ses compositions et d’une vision musicale innovante et sophistiquée, le chanteur n’a pas eu de mal à convaincre l’ambitieux Foster de lui donner une nouvelle chance. Avec deux titres caractéristiques de cette période (refusés par RCA), Orbison expérimenta dans un format rock conçu pour la radio, mais sans succès. Mais lors de cette nouvelle phase qui débutait, son approche restait la même, décrivant des scènes et personnages très cinématographiques, mis en scène par de la musique :

Je marche vers le côté blues de la ville/Où il n’y a ni bonheur ni joie/Au bout d’une longue rue sombre/J’ai vu un petit marchand de journaux/Petit marchand, j’ai de mauvais nouvelles pour toi/Petit marchand, ma chérie et moi c’est fini

— Roy Orbison & Joe Melson, Paper Boy, 1959

Moins originale, la face B du 45 tours utilisait des stéréotypes rock. Mais clairement, avec Paper Boy en face A, Orbison avait déjà choisi la direction du mélo-drame orchestré. Son approche révélait une vulné-rabilité désespérée contrastant avec les professions de foi viriles de la plupart de ses pairs. Cette fragilité ostensible, qui donnait toute leur importance à de mystérieux personnages féminins, des princesses romantiques pour lesquelles son cœur se déchirait, séduisait les femmes et touchait discrètement la sensibilité des hommes.

Cette indéniable originalité laissait déjà entrevoir que le rock pouvait véhiculer des sentiments et images plus complexes que ce que l’on connaissait jusque là : le rock mettait tout à coup des personnages fictifs en scène. Lou Reed et Bob Dylan, qui au milieu des années 1960 introduiraient dans le rock des paroles d’une grande maturité, ont vite été suivis dans ce sens par les Anglais des Kinks, des Beatles, des Who. Tous étaient de grands admirateurs de Roy Orbison, qui utilisait déjà cette musique comme une forme artistique au même titre que le théâtre, le cinéma ou la littérature.

Outre ces qualités de fond, Orbison fut l’un des précurseurs du nouveau son de Nashville créé par son allié Fred Foster et les producteurs Owen Bradley, Chet Atkins et Sam Phillips. Il dirigeait lui-même toutes ses séances de studio. Avec le crack Grady Martin à la guitare12, les Jordanaires ou les Anita Kerr Singers aux chœurs, il utilisait une équipe de musiciens chevronnés, surnommée à Nashville « The A-Team » (voir disco-gra-phie). Ils avaient enregistré avec des centaines d’artistes de poids, comme Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Patsy Cline, Johnny Burnette, les Everly Brothers…

Les Drifters, groupe vocal afro-américain à succès chez Atlantic, avaient récemment été les premiers à oser incorporer des cordes dans leurs enregistrements. Ils le firent dans le cadre d’un style naissant, la soul music13. Outre ses compositions très soignées et sa voix unique, puissante, évoquant en même temps la fragilité, Orbison allait apporter des arrangements raffinés où les cordes tenaient une place innovante. Sa façon discrète d’utiliser les violons avec parcimonie, goût et légèreté évoquent un mot : l’élégance. Avec leurs nouvelles compositions, comme le classique Uptown, chargé de chœurs inspirés par des phrases issues du style « doo wop » et savamment élaborés, avec leur son frais Orbison et Melson détenaient la formule musicale-clé de la pop du début des années 1960 : l’archétype de ce qu’on appellerait bientôt les années Kennedy (1961-1963). Entre la dramaturgie des slows dépeignant des perdants terrassés par la vie et des rocks aux paroles intelligentes, au tempo médium conçu pour la danse et la radio, cette musique émouvante, parfois même déchirante, à la fois légère et lourde de sens faisait partie de la bande son de l’Amérique arrogante de la conquête spatiale, du progrès et de l’opulence. Elle était l’air du temps dans une abondance luxuriante propre aux États-Unis d’alors. Monté au numéro 72 des ventes, son deuxième single pour Monument, « Uptown » où un jeune homme rêve des beaux quartiers, serait son dernier bide. Sa voix phénoménale (trois octaves incluant une bonne maîtrise de la voix de fausset — une fausse voix de tête et une vraie voix de gorge selon Alan Clayson, son biographe — qui lui permettait de monter très haut) allait prendre son envol. Elle servirait des compositions singulières, où ses envolées audacieuses font bien souvent penser à l’opéra — comme dans le final de Only the Lonely, qui devint son premier titre à se vendre à vendre un million d’exemplaires.

Only the Lonely

« Roy Orbison était le vrai maître de l’apocalypse roman-tique que tu redoutais, il savait ce qui allait se passer quand tu murmurais « Je t’aime » à ta première copine : tu allais mal. Roy était le plus cool des perdants pas cool. Avec ses lunettes noires couleur bouteille de Coke, ses trois octaves, on aurait dit qu’il aimait remuer le couteau dans la plaie du manque d’assurance adolescent. »

— Bruce Springsteen, South by Southwest 2012

Selon l’écrivain américain Ken Emerson, pendant les quatre années suivantes ses disques ont « apporté une nouvelle splendeur au rock ».

« Ses mélodrames orchestraux avaient pour seuls rivaux ceux de Phil Spector. Ils étaient en contraste frappant avec la musique des Everly Brothers, qui avec quasiment les mêmes musiciens, et dans le même studio, n’of-fraient qu’une musique au son très léger si on les compare14 ».

Début 1960, Roy Orbison et Joe Melson écrirent Only the Lonely. Roy se mit en route pour Nashville afin de l’enregistrer. Peu sûr de lui, il n’oublia pas qu’il était surtout connu pour ses compositions et il s’arrêta à Memphis pour proposer son morceau à Elvis Presley, devenu entretemps une absolue superstar. Mais il était tôt le matin et Elvis dormait encore. Une fois arrivé à Nashville, Roy n’a pas résisté à rendre visite aux Everly Brothers, qui par chance pour lui refusèrent sa chanson car ils venaient eux-mêmes d’en écrire une. Il se décida alors à l’enregistrer lui-même et y incorpora un passage final legato où, exploitant à fond sa voix, il s’envola vers des hauteurs jusqu’ici inédites dans le rock. Abandonné par son amour, il se lamentait une fois de plus sur son sort :

Seuls les solitaires/Savent comment je me sens ce soir/Seuls les solitaires/savent que ressentir cela n’est pas juste

— Roy Orbison & Joe Melson, Only the Lonely, 1960

Roy Orbison dirigeait tout, concevait tout.

« Si tu fais une maquette et que tu obtiens quelque chose de vraiment bien tu ne peux pas… c’est difficile de le retrouver en studio. Alors je fais des maquettes mais je fais attention à ce qu’elles ne soient pas trop bonnes, juste assez pour donner une bonne idée, comme ça quand tu fais le disque tu te donnes à fond. Mais même si tu n’oublies pas de faire très brut, tu peux te retrouver avec un résultat qui balance vraiment bien quand même et quand tu le refais en studio c’est un peu trop propre… mais enregistrer des bandes de démonstration ça t’apprend à faire ce qu’il faut en studio. Et si tu as un groupe, il va t’aider, il va t’apporter quelques idées fraîches. Dans les années soixante je faisais toujours de la pré-production, je savais exactement ce que je voulais avant d’entrer en studio15. »

Le mixage de l’ingénieur du son Bill Porter était entièrement axé sur les voix : la rythmique était presque secondaire. Le résultat mettait en valeur la voix de Roy, et Only the Lonely monta au numéro deux aux États-Unis, numéro un en Angleterre et en Australie. Du jour au lendemain, Roy Orbison était une star en demande sur les scènes de trois continents. Il partit trois semaines en tournée avec Patsy Cline et installa sa famille à Nashville. Blue Angel, le single suivant, n’est monté qu’au n°9 ; Décidés à laisser derrière eux l’influence du doo-wop noir (I’m Hurtin’) un temps, les deux auteurs-compositeurs voulurent alors pousser leur logique jusqu’au bout en s’inspirant du « Boléro » de Maurice Ravel. La voix de Roy porterait ce cheval de bataille Running Scared jusqu’au sommet — jusqu’au n°1 des ventes, et n°9 en Angleterre : un triomphe. Accompagné par un orchestre en studio, il ne parvint pas à atteindre le la trop haut pour sa voix de tête ; Lors de la troisième prise, à la surprise générale c’est avec sa voix naturelle qu’il l’atteint. La chanson décrit un homme jaloux qui surveille son amour de crainte qu’un autre homme ne lui dérobe. L’intensité monte au fil du morceau jusqu’à l’apothéose vocale finale. Partisan de la spontanéité, il était capable d’enregistrer sa voix phénoménale en une ou deux prises.

« Je veux que les gens croient à ce que je chante. Dans mon cas, si j’enregistre la chanson, je chante deux fois. Je chante une fois pour m’échauffer, et puis une deuxième fois, qui est souvent la prise qu’on garde. Cette fraîcheur serait perdue si je la chantais plein de fois, je pense. Ça sonnerait trop répété, trop planifié, trop calculé. En général je fais comme ça. Et puis de cette façon c’est aussi une surprise pour moi et une grande joie quand je réécoute la prise. Je fais de mon mieux. Habituellement tu fais du mieux que tu peux, tu recommences — et c’est fini ! Il y en a qui prennent des centaines et des centaines de prises. Je ne sais pas comment ils font ! »16

D’autres perles suivirent, comme Summer Song, le n°30 Candy Man, le n°2 Crying et le n°4 Dream Baby. The Crowd, Working for the Man et Leah furent de nouveaux succès tandis que son deuxième fils naissait en 1962.

Un jour de 1962, Roy Orbison a oublié ses épaisses lunettes de vue dans un avion et dut porter ses lunettes de soleil (de vue) sur scène ce soir-là. Ses verres fumés Wayfarer semblaient protéger cet homme maladivement timide, qui souffrait de trac, et il décida de ne plus s’en séparer. Plus mystérieux que jamais, habillé de noir, aux cheveux de jais, concentré sur sa voix, immobile sur scène, il créa spontanément un personnage énigmatique. Il n’était pas très présent dans la presse en raison de son phy-sique ingrat — il était pourtant une idole pour lesquelles les adolescentes se pâmaient à tous ses concerts — et en conséquence, sa photo n’apparaissait pas sur ses 45 tours.

En 1963 il partit en tournée anglaise avec les Beatles, alors au tout début de leur succès, et devint amis avec eux. Admiré par Elvis comme par les Beatles, sa carrière culminerait en 1965 avec son célèbre et énorme succès « Pretty Woman », quelques jours avant qu’il ne se brise le pied dans un accident de moto qui brisa aussi sa carrière. Dépassé par les nouveaux sons — Beatles, psychédélisme — il signa avec MGM avec qui il ne parvint pas à retrouver le son si particulier qu’il avait créé. Les disques Monument firent faillite et ses succès disparurent de la circulation pendant près de vingt ans.

Il dut aussi supporter un échec au cinéma et le décès dramatique de son épouse dans un autre accident de moto (1966). Remarié avec Barbara, il endura l’an-nonce de la mort de ses deux premiers fils (1968) dans l’incendie de leur maison familiale à Henderson (Tennessee). Pendant les deux décennies qui ont suivi sa glorieuse période Monument, Roy Orbison a gardé un profil bas, jouant occasionnellement, enregistrant quelques albums sans succès. Il lui fallut attendre 1988 pour faire un retour aussi fulgurant qu’inattendu avec les Traveling Wilburys — et une fois de plus tragi-quement marqué par la malchance, puisqu’il n’a pu vivre pour en profiter.

Bruno BLUM

Merci à Christian Lebrun, Barbara et Roy Orbison.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Film documentaire des Traveling Wilburys, 1988.

2. Roy Orbison à l’auteur, Paris, place des Vosges le 31 novembre 1988, cinq jours avant son décès.

3. Lire la biographie de John Kruth Rhapsody in Black: The Life and Music of Roy Orbison (Backbeat Books, 2013).

4. Tryin’ to Get to You avait déjà été enregistré par Elvis Presley le 11 juillet 1955. Sa version, ainsi que la version originale gravée en 1954 par les méconnus Eagles, figurent sur Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine vol. 1 - 1954-1956 (FA5361) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter dans cette collection l’anthologie Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

6. Cité dans la notice de Ken Emerson in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press/Random House, New York, 1976.

7. Lire le livret et écouter Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160) dans cette collection.

8. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA5402) et le volume deux 1958-1962 (FA5422) dans cette collection.

9. Lou Reed à l’auteur, Paris, 1989.

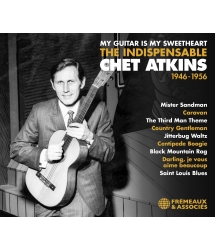

10. Retrouvez Chet Atkins sur les anthologies Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426), Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz, Blues R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) et Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007) dans cette collection.

11. Roy Orbison à l’auteur, Paris, place des Vosges le 31 novembre 1988.

12. Lire le livret et écouter Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423) dans cette collection.

13. Écouter Roots of Soul Music 1928-1962 (FA5430) dans cette collection.

14. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll (Rolling Stone Press, New York 1976).

15. Roy Orbison à l’auteur, Paris, place des Vosges le 31 novembre 1988.

16. Roy Orbison à l’auteur, Paris, place des Vosges le 31 novembre 1988.

Roy Orbison

The Indispensable 1956-1962

By Bruno Blum

He has got one of the best voices ever in pop music.

— His producer Jeff Lynne (Electric Light Or-chestra)1

Rediscovered in 1987 when David Lynch used his song “In Dreams” on the soundtrack of his off-beat film masterpiece “Blue Velvet”, Roy Orbison (b. April 23rd 1936, d. December 6th 1988) suddenly found himself inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Then he appeared in the film of a famous concert where he was accompanied by a few well-known admirers: Tom Waits, James Burton, Jackson Browne, T-Bone Burnett, Bonnie Raitt, k. d. lang, Jennifer Warnes, Elvis Costello, and Bruce Springsteen! Against all expectations, shortly afterwards Orbison began recording a new album, Mystery Girl, and he founded a new vocal group fea-turing none other than the singers Jeff Lynne (Electric Light Orchestra), Tom Petty (Heartbreakers), his old friend and ex-Beatle George Harrison — and Bob Dylan in person. Calling themselves The Traveling Wilburys they recorded two albums which were smash hits, and Roy Orbison was suddenly besieged by offers to play concerts. In the course of this unthinkable return to the scene after some twenty years of setbacks and personal tragedies, Roy also finished a new solo album with the aid of Bono (U2), Elvis Costello and Jeff Lynne. It was another international hit, and the single “You Got It” taken from the album went to N°9 in the U.S. charts. Tragically, at the end of 1988, Roy Orbison died of a heart-attack (he smoked heavily despite undergoing triple bypass surgery in 1977). His death came just days before the record’s release, and he never saw it become yet another hit; nor did he have time to receive the royalties due to him as a member of the Traveling Wilburys. He was only 52. Five days before his death, Fate would have it that I was the last person to interview this legend of American rock… and this is what he said to me in the offices of Virgin Records:

“Faith, that’s all it takes. A lot of people I meet in my travels, they say ‘What’s your advice?’, and I say, ‘Don’t give up; even if you do it just for yourself.’ But I know in my own career… had I stopped a week before… certain things happen. Before certain events. If I’d said, ‘No, I’m not going to tour before the Beatles tour, or the Stones tour, the Beach Boys tour…’ Or if I had not gone to Nashville to meet with this guy who’d never made records before… he was promotion man for Mercury. He decided he’d try to make records and he borrowed some money, and got Chet Atkins to help him make a record. It went to number one. So you just keep doing it and have faith in yourself.”2

The Wink Westerners

He was born Roy Kelton Orbison in Vernon, north Texas, some two hours away from Dallas, a little town on the Oklahoma border situated on the Chisholm Trail along which drovers used to take livestock into Kansas. His parents Nadine Schultz and Orbie Lee Orbison were seeking work during the Great Depression and had taken their children to settle in Fort Worth, Texas, before World War II. Roy went to Denver Avenue Primary School in Fort Worth but a polio epidemic caused the family to return to Vernon. Their next stop was the Texan town of Wink, which Roy dreamed of leaving due to pure boredom. Like his future friend Elvis Presley, who later became one of his great admirers, and like all well-raised children in the South, Roy was self-effacing and showed exemplary politeness.3 He was also unhappy and, plagued with poor sight like all the Orbisons, he never went without his thick lenses. He was given a guitar for his sixth birthday.

Orbie, Roy’s father, was a mechanic; he decided that his future lay in the oil industry and slowly worked his way up to become a technician at an oil-well. He used to play country guitar — “Jimmie Rodgers songs especially” — and taught his son to play a few chords. The boy quickly discovered a passion for music, and, lacking in confidence, he believed that his only chance of success was to work hard on his guitar. His uncle played blues and taught him what he could. But Roy preferred his father’s country style: the first song he mastered was “You Are my Sunshine”, a cover of an Oliver Hood song made famous by Jimmy Davis, the country singer who later became Governor of Louisiana (and made it the State’s official song).

Little Roy Orbison admired country singers Bob Wills and Ernest Tubb, whom he saw in Fort Worth when they came to advertise a brand of milk, standing on the back of a truck. Roy was acquiring a habit of singing with his uncles and cousins, who were professional musicians; he was only eight at the end of the war, but began appearing on radio shows where he sang covers of country records ‘live’ over the air, or “Joli Blon”, a zyde-co number. He also liked blues singers and Tex-Mex music, but most of all he had a passion for the country stars Lefty Frizzell and Hank Williams. When he was ten, Roy sang on a medicine show selling health elixirs, and soon he was a hit at school when he sang Grandpa Jones’ “Mountain Dew”. When he was thirteen he hosted his own show on Radio KERB in Kermit.

Roy didn’t like his very light hair-colour and began dyeing it black, something he would continue to do for the rest of his life. After he became a student in Wink, Roy formed the Wink Westerners (1954) — they played compositions by Frizzell and Hank Williams —, choosing them from members of the group at Wink High School, including a teenager who played an amplified mandolin. Roy accompanied himself on guitar, playing various hits of the period, among them “In the Mood”, “Moonlight in Vermont”, and country numbers by Webb Pierce. His group played in honky-tonk bars, dance-halls and various parties in the area, (notably at a fund-raising event for his High School Principal, who was campaigning to be President of the local Lion’s Club.) When someone offered Roy $400 for a concert, he realized he might turn to a career as a professional, but even so, he still went to North Texas State College to study geology in the event that music didn’t turn out to be profitable. The least you can say about his education is that Roy, when compared with other Fifties rock stars, had already gone much further… But his grades were getting worse, and at the end of the ‘54/’55 school-year he was already thinking about dropping Geology to become a teacher instead.

The Teen Kings

When he heard Elvis’ first record — a cover of Arthur Crudup’s fast blues “That’s All Right” — Roy “didn’t understand” what Elvis was trying to do: a White man playing rock (i.e. the music par excellence of Black people) took him by surprise. The B-side was more reassuring: “Blue Moon of Kentucky”, a version of Bill Monroe’s supremely-White bluegrass number. Roy was living in Odessa, Texas, in 1955 (he was a student at North Texas State University in Denton), and he discovered Presley onstage in nearby Dallas. The collective hysteria which surrounded Elvis when he travelled had begun, and Roy was impressed by the young singer: he envied him. So he formed another group, called it The Teen Kings, and set up an appearance on a show televised by KMID in Midland, Texas, in around September 1955 (he arranged it through Cecil “Pop” Holifield, a contributor to Billboard magazine who also ran record-stores in Midland and Odessa.) “Pop” Holifield also promoted concerts for Sun artists Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley, and he had Cash as a guest on the same show. So Johnny Cash met Roy Orbison; he listened to him, and invited Roy to one of his concerts on October 12th 1955 at Midland High School, where Elvis, a rising star, was topping the bill. He introduced him to Elvis, and Cash and Presley tried to persuade their producer at Sun to give Roy an audition. In vain.

Bobbie Jean Oliver, a singer/accordionist who often appeared with Roy and the Teen Kings (she was dating James Morrow, a member of the group), convinced her parents to finance a record by Roy and his Teen Kings. At Norman Petty’s studio in Clovis, New Mexico, they recorded their first 45rpm single Ooby Dooby on March 4th 1956, a song written by two fellow-students. Trying to Get to You was the B-side.4 The record was issued on the Je-Wel label created for the occasion by Chester Oliver (Jean Oliver’s father) and singer Weldon Rogers (Jean’s ex-husband). It just can’t be found these days, and it remains a legendary collectors’ item: the tapes disappeared from Petty’s studio in 1984, and the recordings have never been reissued. On the day it was released, Orbison gave a copy of this demo record to Pop Holifield, who called Sun studios to tell Sam Phillips it was selling well. He insisted that Sam should audition Roy and his Teen Kings, and Phillips called him back a few days later to have them come and make a record at his studio in Memphis. There was no audition. Roy’s father had to sign the Sun contract for him: his son was still under-age. Since Roy had signed his Je-Wel contract while still a minor, it wasn’t valid, and so Sun took out an injunction to have his first disc with the Teen Kings removed from sale — despite the fact that several thousand copies had been pressed via Norman Petty — at the time, Petty was also the less-than-scrupulous manager/publisher of Buddy Holly — so the whole business cost Jean Oliver’s poppa a lot of money… The original record vanished from the shelves.

Sun Records

Sun had launched Elvis Presley a year earlier and by the spring of 1956, competition was rife amongst white rockers. In the midst of racial segregation, the brilliant producer Sam Phillips was seeking out other white artists capable of singing in a style close to Afro-Ame-rican rock, to which he added a more “country” flavour. And the formula worked. The little Sun Studio’s legendary recording-sessions had just given birth to the rockabilly boom: they’d made stars of Elvis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and soon Jerry Lee Lewis. Phillips had genuinely broken into the great, white rock-market.

Less popular than his peers, Roy Orbison still remained N°5 on the list of Sun’s classic rock artists.5 At the age of 20 he moved into Sam Phillips’ Memphis home with his girlfriend Claudette Frady, who was only 16 and had a room of her own. At the end of March 1956 Roy re-recorded Ooby Dooby (even though he’d had enough of the song by then), and Go! Go! Go! (Movin’ on Down the Line), which was soon picked up by Jerry Lee Lewis. These two new versions are the ones which open this set.

“When we were recording “Ooby Dooby”, Sam Phillips brought me out a set of thick 78 records and said ‘Now, this is the way I want you to sing.’ And he played ‘That’s All Right’ by Arthur Crudup. I sort of took a little notice and he said ‘Sing just like that… and like this.’ And he put on a song called ‘Mystery Train’ by Junior Parker. And I couldn’t believe it… And I said, ‘Now Sam, I want to sing ballads. I’m a ballad singer.’ And he said ‘No, you’re gonna sing what I want you to sing. You’re doing fine. Elvis was wanting to sing like the Ink Spots or Bing Crosby,’ and he did the same thing for him, did the same thing for Carl Perkins.”

— Roy Orbison6

Roy Orbison and his Teen Kings signed with agent Bob Neal, Presley’s former impresario and the owner of the Stars Incorporated agency. They found themselves touring dance-halls, and they played in movie drive-ins between films. They appeared on the same bill as Sonny James, Johnny Horton and Johnny Cash, and later Jerry Lee Lewis, Warren Smith and Carl Perkins, the creator of the rockabilly anthem “Blue Suede Shoes”, plus other country and rockabilly artists. In the midst of the rock wave, carried by Sun’s original sound and distributed by Chess in the north of the country, Ooby Dooby reached N°59 in the Billboard charts, selling 200,000 copies. Imitating Elvis, Roy shook his way across the stage as best he could:

“We all danced and shaked and did everything we could do to get applause because we had only one hit record, ‘Ooby Dooby.’”

— Roy Orbison

His other records, however, didn’t sell: there was enormous competition from dozens of artists who were recording rockabilly like there was no tomorrow. Roy Orbison was only a year younger than Elvis, who liked his voice a lot and became a genuine friend. Like Elvis and Little Richard, Chuck Berry or Gene Vincent, Orbison belonged to the second generation of rockers, the vintage which caused white audiences to discover the style after the seminal rock of Louis Jordan, Tiny Bradshaw or Roy Brown, and after some country boogie highlights.7 Yet Orbison was some-one quite apart. While he appreciated black rock, he always remained rather impervious to the Afro influ-ences which contributed to the success of his Sun stable-mates. Orbison’s rockabilly, in theory a hybrid of both cultures, stayed distant from the influence of the black gospel and blues which marked the first, famous recordings of Elvis, Carl Perkins or Gene Vincent.8 Like Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison followed the same direct line down from country-music’s legacy. Shy, quiet, sensitive, refined and intelligent, the young man wasn’t that handsome: his glasses with thick lenses were a perma-nent fixture; he dyed his hair in secret; he didn’t drink; and he was never comfortable when surrounded by noisy rockers…

I’d like to be a bad boy but I’m afraid to get hurt/I’m chicken hearted

— Roy Orbison, Chicken Hearted, 1956

While his rocker-coreligionists strutted in arrogance with displays of raw virility, the sensitive Roy Orbison preferred singing the torments of hopeless, despairing love. He was vulnerable, hard-working, and he had complexes. But he took great care over his compositions (unlike Roy, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis didn’t write most of their songs themselves), going deeper into melodies which expressed his disappointments and chagrin. His ballads were turned down by Sam Phillips, who only wanted up-tempo rock. Jack Clement, the producer (and discoverer) of Jerry Lee Lewis at Sun, even told Roy that he’d never have a hit with a ballad. Given Roy’s career, that was a serious error…

Roy’s producer wasn’t interested in Roy’s musical leanings or his ideas. And Roy thought that Sam Phillips, deeply in debt despite the sale of Presley’s contract to RCA, wasn’t professional enough because, “The industry passed him by from one day to the next and he didn’t even notice.” Even so, his Sun years produced a few classics, like Ooby Dooby, Rockhouse (later recorded by Bobby Fuller, The Stray Cats, etc.) and Go! Go! Go! (which was successfully picked up by Jerry Lewis under the titles “Down the Line” and “Movin’ on Down the Line”). Buddy Holly would record several of Roy’s compositions: “You’ve Got Love”, “A True Love Goodbye” and “An Empty Cup!” Not to mention “Claudette” (the girl he married in 1957), a great hit for The Everly Brothers. The royalties that would come in from that release (spring 1958) probably restored Roy’s confidence. He made a down-payment on a Cadillac and found the courage to leave Sam Phillips. Sun was incapable of following him artistically: Roy had sophisticated, romantic orchestrations in mind, for songs that would bring dreams to the princess who slept inside every young girl. Nor did Phillips understand his potential as a composer. The truth was, he appreciated Roy Orbison mostly for his mastery of the electric guitar. Singers who ventured forward to play solos were rare, but Orbison, a hard worker, was an excellent guitarist. It’s ironic that his great hits of the Sixties (cf. CD2) featured his exceptional voice — he hadn’t completely mastered it in 1956 —, and that he didn’t play guitar on any of his most famous songs. But when he was just beginning, it was his original guitar-playing which people noticed the most.

I learned to play guitar by trying to copy the solos on Roy Orbison’s first records. — Lou Reed9

RCA Victor

In 1957 Roy Orbison was constantly touring, but it didn’t provide a decent living. He couldn’t find enough gigs to pay his instalments and had to return the Cadillac. Dependent on his family and friends to find a roof for himself and his young bride, in 1958 he abandoned the stage completely for seven months; his future looked bleak. Keeping a tight grip on his guitar, he continued to write songs in his tiny apartment and offered them to the publishers Acuff-Rose, who placed songs with well-known artists. He had no success there either. In 1958, reactionary America was better-organized to resist the Afro-American influences incarnated by rock and the Elvis phenomenon. A whiter sound with a stronger country feel — incarnated by Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Elvis himself — was in demand, and rock’s centre of gravity had moved to Nashville, Tennes-see, on the border dividing south from north. Roy also tried to position himself as a singer, with songs written by others, and he recorded those with guitar-giant Chet Atkins,10 although they met with little success. Atkins was a virtuoso guitar player revered by Roy and also by Elvis Presley’s regular guitarist Scotty Moore. Atkins was a celebrity and accepted to play on Elvis’ records for RCA; he also had contacts. They recorded “Seems to Me”, a Boudleaux Bryant composition, and Bryant would later describe Orbison as “a timid, shy kid who seemed to be rather befuddled by the whole music scene. I remember the way he sang then: softly, prettily but almost bashfully, as if someone might be disturbed by his efforts and reprimand him.” But RCA only took two songs, and Roy continued to live poorly, together with his wife and young child. He was often away, giving badly-paid concerts, and wrote his songs alone, taking refuge in his car. Roy had also met Joe Melson, the singer with the Cavaliers rockabilly group. Melson was also from north Texas, where he was raised on a farm and developed a passion for music. Anchored in the country and rocka-billy traditions like Roy, Melson had started composing in a style influenced by rhythm and blues, and he was an open-minded character inclined to be creative. It was at his home in Midland, west Texas, that he teamed up with Roy Orbison. The two friends came up with songs whose melodies were more ambitious than Roy’s basic rocka-billy numbers, which were constructed around three-chord blues formats (1-4-5) in twelve bars.

“Writing with a partner is really good when you get to a point where you’ve got nothing going. You just kind of… your ideas just kind of stop and someone else will just pick it up. And even if it’s not what you want, you can go from there and say ‘Yeah, that’s pretty good, but this is better’, and the other guy says ‘No, wait a minute, I’ve got something!’ So it works that way.”

— Where do you stop?

— (laughs) “You stop usually when there’s a good feeling going, and we’re all arrangers as well, and kind of know when a piece has said what it needs to say.”

— Roy Orbison11

Monument Records

It was then that Wesley Rose, his agent, sent Roy to Fred Foster, the young producer who ran Monument Records. Foster was born in North Carolina on July 26th 1931, and after the death of his father he had to take care of his mother and the family’s farm. Robust, ambitious and independent, at the age of seventeen he left to try his luck in Washington D.C. and later worked for ABC-Paramount and Mercury. Those two record-companies had catalogues aimed at large audiences, and they were capable of meeting demands from major radio and television stations, working with great stars and producing high-quality records. While continuing to work in promotion for Mercury, Foster became a record-distributor in Baltimore. By the age of 27 he had a solid background in the industry, and in March 1958 the intrepid and ambitious young man invested all his savings to found Monument and its publishing-arm Combine Music. His label took off at once with Billy Grammer (a great country guitarist), Billy Graves, Dick Flood (“The Three Bells”), Jerry Byrd (a country steel-guitarist who loved Hawaiian music) and Bob Moore (a great country bassist who was behind the 1961 instrumental hit “Mexico”.) As soon as he had his first hit (1959) Fred Foster bought out his associate Buddy Deane (a DJ with radio station WITH in New York) and became sole owner. He established his business in Nashville, the country music capital where great mu-sicians also lived — and out of which evolved the new sound that dominated America in that period. As soon as he arrived in Nashville, Foster, still a novice in production matters, met Roy Orbison, who was still looking for the means to turn what he could hear in his head into something tangible. Armed with his original ideas, his compositions, and a musical vision that was excitingly new and sophisticated, Roy Orbison had little trouble convincing the ambitious Fred Foster to give him a new chance. With two titles characteristic of this period (both refused by RCA), Orbison experimented unsuccessfully with a rock format intended for radio; but during this phase still in its infancy, Roy’s approach stayed the same, with material describing scenes and characters as if this was cinematography, and his music the filmmaker:

I walk down to the blue side of town / Where there’s no happiness no joy / Down at the end of a long dark street / I saw a little paper boy / Paper boy, paper boy I’ve got bad news for you / Paper boy, paper boy, me and my baby are through.

— Roy Orbison & Joe Melson, Paper Boy, 1959

The B-side was less original, resorting to rock stere-otypes, but visibly, with Paper Boy as the record’s A-side, Orbison had already chosen the direction of orchestrated melodrama. His approach revealed a despairing vulnerability which contrasted with the virile professions of faith declaimed by most of his peers. This ostensible fragility — which gave mysterious female characters, romantic princesses for whom his heart was breaking, all their importance — was something which women found very seductive, and which discreetly reached out to masculine sensibilities.

This undeniable originality was already giving a glimpse of the fact that rock could convey feelings and images which were more complex than any seen up until then: suddenly, rock was staging fictional characters. Lou Reed and Bob Dylan, who introduced extremely mature lyrics into rock in the mid-Sixties, were quickly followed in this direction by the writers in the British bands The Kinks, The Beatles, The Who… All of them were great admirers of Roy Orbison, who was already using this music as an art form in the same way as theatre, film or literature.

Apart from those basic qualities, Orbison was also one of the precursors of the new Nashville sound created by his ally Fred Foster and producers Owen Bradley, Chet Atkins and Sam Phillips. Orbison ran his own studio-sessions. With guitar-ace Grady Martin,12 and with The Jordanaires or the Anita Kerr Singers as back-up vocalists, he fronted a team of renowned musicians — nicknamed “The A-Team” in Nashville (cf. discography) — who recorded with hundreds of heavyweight artists, including Elvis, Buddy Holly, Patsy Cline, Johnny Bur-nette and the Everly Brothers.

The Drifters, a hit Afro-American vocal group with Atlantic, had recently been the first to dare using strings on their recordings, and they did so because of the budding soul music-style.13 Roy Orbison, in addition to his careful compositions and unique voice, an instrument that had power and evoked fragility at the same time, would bring refined arrangements to recordings in which he innovated with strings. His discreet way of using violins sparingly, lightly and with taste, could be summed up in a word: elegance. With their new recordings — like the classic Uptown, laden with vocal backing inspired by phrases that came from the “doo wop” style and were skilfully elaborate — Orbison and Melson had a fresh sound which was the key music-formula in early Sixties’ pop: it was an archetype in what would soon be known as the Kennedy Years (1961-1963). Situated in between dramatic slow numbers — depicting losers struck down by life’s misfortunes — and rock songs with intelligent lyrics — medium-tempo numbers intended for dancing and radio — this moving, sometimes even heartrending music, simultaneously light and yet heavy with meaning, formed the soundtrack of an arrogant America whose preoccupations seemed to be the conquest of Space, progress and opulence. It was the prevailing mood in the period of lush abundance which was proper to America in that period. Reaching N°72 in the sales-charts, his second single for Monument, “Uptown” — the tale of a young man’s dream of living in a fine neighbourhood — would be Roy’s last flop. He had a phenomenal voice. It covered three octaves and showed he could handle a falsetto — his biographer Alan Clayson said he had a falsetto voice and that it “came not from his throat but deeper within” — and it allowed Roy to climb high in the register. Roy would climb higher, too: his voice would serve some very singular compositions where he took flight daringly — if often made you think you were at the opera — as in the ending to Only the Lonely, which became the first Roy Orbison song to sell a million copies.

Only the Lonely

“[Roy Orbison] was the true master of the romantic apocalypse you dreaded, and knew what was coming after the first night you whispered ‘I Love You’ to your first girlfriend. You were going down. Roy was the coolest uncool loser you’d ever seen. With his Coke-bottle black glasses, his 3-octave range, he seemed to take joy sticking his knife deep into the hot belly of your teenage insecurities.”

— Bruce Springsteen, South by Southwest 2012

According to American writer Ken Emerson, over the next four years his records “brought a new splendour to rock”.

“His orchestral melodramas, rivalled only by Phil Spector’s, were in striking contrast to the comparatively thin music the Everly Brothers made in the same studio with much the same personnel”.14

Early in 1960, Roy Orbison and Joe Melson wrote Only the Lonely. Roy went off to Nashville to record it but, lacking in confidence, he remembered he was known mostly for his compositions, and stopped in Memphis en route to offer his new song to Elvis Presley, who by then was by now an absolute superstar. But it was early morning and Elvis was still sleeping. Once he arrived in Nashville, Roy couldn’t resist paying the Everly Brothers a visit, and luckily they turned the song down (they’d just written one of their own…) So Roy decided to go ahead and record it himself, adding a final legato passage where, making use of his voice to the limit, he soared into the stratosphere, a first in rock. Abandoned by the woman he loved, he mourned his loss yet again:

Only the lonely / Know the way I feel tonight / Only the lonely / Know this feeling ain’t right.

— Roy Orbison & Joe Melson, Only the Lonely, 1960

Roy Orbison controlled everything, conceived every-thing: “If you make a demo and you get something really wonderful, you can’t… it’s hard to get back in the studio so… so demos, I make pretty good ones, but not super good, just give them a good idea, so that when you make the record you can really punch through. […] It does get tricky, but that’s a lot of fun, too. If you keep in mind when you make a demo to make it very raw, even then sometimes you’ll get a real rough cut that really swings and you get in the studio and it’s a little too good… but making a demo teaches you what to do in the studios. That’s why if you have a band, you have a group, that’s what helps you in the studio, a few fresh ideas. I used to always do pre-production, I had everything figured out before I went into the studio.”15

Sound-engineer Bill Porter centred his mix entirely on the voices; the rhythm parts were almost secondary. The result highlighted Roy’s vocal and Only the Lonely reached N°2 in The United States, topping the charts in Britain and Australia. Overnight, Roy Orbison was a star, and venues clamoured for him on three continents. He went on tour for three weeks with Patsy Cline, and moved his family to Nashville. Blue Angel, his next single, only reached N°9 and, deciding to rest the black doo-wop influence (I’m Hurtin’) for a while, the two singer-songwriters opted to follow their logic to the limit, inspired by Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero”: Roy’s voice took the war-horse Running Scared to the summits — it was a N°1 seller, and N°9 in Britain. A triumph. Roy was accompanied by a studio-orchestra, but he couldn’t reach a high A, a note beyond his falsetto voice; on the third take, to everyone’s surprise, he made it… using his normal voice. The song describes a jealous man keeping an eye on his love for fear another man will steal her away. The intensity mounts throughout the piece until the vocal apotheosis of the finale. Always a man with a taste for the spontaneous, Roy was capable of recording his phenomenal voice in one or two takes.

“I want people to believe what I sing. In my case, if I sing the song, I sing twice. I sing once as a warm-up, and then I sing it one more time, which is often the one we keep. So the freshness of that would be lost had I sung it a lot of times, I think. I would sound too rehearsed, too planned and too calculated. I mostly do that. So then it’s also a surprise to me and it’s also a great joy to hear it. As best I can do it. And you usually do it the best you can, then you do it once more over the top. Then you’ve done it. There are people who take hundreds and hundreds of takes. I don’t know how they do it!”16

Other gems followed, like Summer Song, the N°30 hit Candy Man, the N°2 Crying and Dream Baby which went to N°4. The Crowd, Working for the Man and Leah were as many hits, coming as Roy’s second son was born in 1962.

One day in 1962, Roy Orbison forgot his thick lenses on an aeroplane and had to wear sun-glasses onstage that night (they had prescription-lenses). His dark Wayfarer glasses seemed to protect this chronically shy man from stage-fright, and he decided he’d never go without them. Now more mysterious than ever, dressed in black with jet-black hair, concentrating on his voice while mo-tion-less onstage, Roy spontaneously created an enigmatic character. He wasn’t very visible in the media due to his unprepossessing physique — although girls swooned in the presence of their idol — and one consequence was that his photo didn’t appear on the covers of his singles.

In 1963 Roy went on tour with The Beatles, then at the very outset of their fame, and they became friends. Admired by both Elvis and The Beatles, Roy saw his career come to an end in 1965, after his enormous hit “Pretty Woman”, only days before he broke his foot in a motorcycle accident — which also broke his career. Out of his depth amidst the new sounds in music — Beatles, psychedelics — Orbison signed with MGM but was unable to rediscover the extraordinary sound he’d created. Monument Records went bankrupt and Roy Orbison’s hits disappeared from circulation for almost twenty years.

Roy also had to endure failure in films and the dramatic death of his wife in another motorcycle accident (1966). After his new marriage to Barbara Jakobs, he had to endure another tragedy when his first two sons died in a fire at their family home in Henderson, Tennes-see. During the two decades following his glorious Monument era, Roy Orbison kept a low profile, occasionally playing and recording a few albums which didn’t sell well. He had to wait until 1988 before making a comeback — as dazzling as it was unexpected — with the Traveling Wilburys, but again, it was marked by tragedy: Roy Orbison didn’t live long enough to enjoy it.

Bruno BLUM

English adaptation: Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Christian Lebrun, Barbara and Roy Orbison.

© FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS 2014

1. Jeff Lynne, Traveling Wilburys documentary, 1988.

2. Roy Orbison speaking to the author, Paris, Place des Vosges, November 31st 1988, five days before his death.

3. Cf. John Kruth’s biography Rhapsody in Black: The Life and Music of Roy Orbison (Backbeat Books, 2013).

4. Tryin’ to Get to You had already been recorded by Elvis Presley on July 11th 1955. His version, together with the original recorded in 1954 by the little-known Eagles, appears on Elvis Presley face à l’histoire de la musique américaine vol. 1 - 1954-1956 (FA5361) in the same collection.

5. Cf. the anthology Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

6. Quoted by Ken Emerson in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press/Random House, New York, 1976.

7. Cf. Country Boogie 1939-1947 (FA160).

8. Cf. The Indispensable Gene Vincent 1956-1958 (FA5402) and its second volume 1958-1962 (FA5422).

9. Lou Reed talking to the author in Paris in 1989.

10. Chet Atkins appears in the anthologies Rock Instrumentals Story 1934-1962 (FA5426), Electric Guitar Story - Country Jazz, Blues R&B, Rock 1935-1962 (FA5421) and Guitare Country - From Old Time to Jazz Times 1926-1950 (FA5007).

11. Roy Orbison talking to the author, Place des Vosges, Paris, November 31st, 1988.

12. Cf. Rockabilly 1951-1960 (FA5423).

13. Cf. Roots of Soul Music 1928-1962 (FA5430).

14. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll (Rolling Stone Press, New York 1976).

15. Roy Orbison talking to the author, Place des Vosges, Paris, November 31st, 1988.

16. Roy Orbison talking to the author, Place des Vosges, Paris, November 31st, 1988.

Discography 1 : 1956-1959

1. Ooby Dooby

(Allen Richard Penner aka Dick Penner, Wade Lee Moore)

The Teen Kings: Roy Orbison-v, g; James Emitt Morrow-electric mandolin; Johnny Wilson aka Peanuts Wilson-rhythm g; Jack Kennelly-b; Billy Pat Ellis-d. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun 242. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., Memphis, March 27, 1956.

2. Go! Go! Go! (Down the Line)

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison)

Same as disc 1, track 1.

3. Tryin’ to Get to You

(Rose Marie McCoy, Charles Singleton)

Same as disc 1, track 1. Sun 1260.

4. You’re my Baby

(J.R. Cash aka Johnny Cash )

Same as disc 1, track 1. Sun 251. September 24, 1956.

5. Rockhouse

(Harold Jenkins aka Conway Twitty)

Same as disc 1, track 1. Sun 251. September 24, 1956.

6. Domino

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips)

Same as disc 1, track 1. Sun 251. 1956.

7. Sweet and Easy to Love

(Sam Phillips)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, eg; Roland Janes-g; James M. Van Eaton-d; The Roses-bv. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun 265. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., Memphis, December 14, 1956.

8. Devil Doll

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison, Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips)

Same as above.

9. The Cause of it All

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, eg; unknown g, b, d. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., Memphis, 1956.

10. Chicken Hearted

(William Justis aka Bill Justis)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, eg; Roland Janes-g; Jimmy Wilson ou Jimmy Smith-p; Martin Willis-s; Stan Kesler-b; Otis Jett-d; C. Buehl-percussion. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun 284. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., Memphis, October 16, 1957.

11. I Like Love

(Jack H. Clement)

Same as above.

12. Fool’s Hall of Fame

(Danny Wolfe, Jerry Freeman)

Same as 10.

13. A True Love Goodbye

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison, Norman Petty)

Same as 10.

14. A Mean Little Mama

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Same as 10.

15. Problem Child

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Same as 10.

16. You’re Gonna Cry

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, eg; unknown personnel, possibly same as 10. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., unknown date.

17. This Kind of Love

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Same as 16.

18. It’s Too Late

(Harold Willis aka Chuck Willis)

Same as 16.

19. I Never Knew

(Samuel Cornelius Phillips aka Sam Phillips)

Same as 16.

20. Lovestruck

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, eg. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., March 4, 1958.

21. One More Time

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison)

Roy Kelton Orbison as Roy Orbison-v, acoustic g. Produced by Samuel Cornelius Phillips as Sam Phillips. Sun Studio, 706 Union Ave., March 4, 1958.

22. I Was a Fool

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison)

23. With the Bug

(Roy Kelton Orbison aka Roy Orbison)