- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

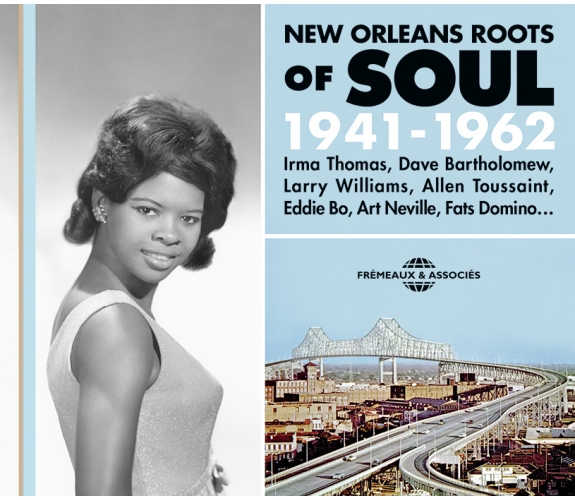

IRMA THOMAS • DAVE BARTHOLOMEW • LARRY WILLIAMS • ALLEN TOUSSAINT • EDDIE BO • ART NEVILLE • FATS DOMINO…

Ref.: FA5633

EAN : 3561302563329

Artistic Direction : BRUNO BLUM

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 3 hours 7 minutes

Nbre. CD : 3

IRMA THOMAS • DAVE BARTHOLOMEW • LARRY WILLIAMS • ALLEN TOUSSAINT • EDDIE BO • ART NEVILLE • FATS DOMINO…

IRMA THOMAS • DAVE BARTHOLOMEW • LARRY WILLIAMS • ALLEN TOUSSAINT • EDDIE BO • ART NEVILLE • FATS DOMINO…

As a music laboratory of great influence in the southern states of America, New Orleans was instrumental in the development of American popular music, and soul in particular. Fantastic New Orleans artists and producers mixed religious and secular music, Indian and Caribbean sounds, voodoo, Jazz and Zydeco… Their soul music was born out of the fusion between those influences and the language and emotions of Gospel, creating a universal idiom that stood the world on its head. In the 32 page booklet accompanying this essential anthology, Bruno Blum provides a commentary of the metamorphosis of Negro spirituals, blues and rock into pure New Orleans soul, thanks to such legendary artists as Lee Dorsey, Irma Thomas, Snooks Eaglin or Eddie Bo. Patrick FRÉMEAUX

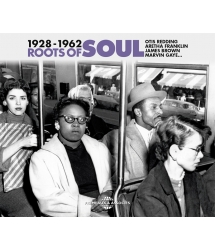

OTIS REDDING • ARETHA FRANKLIN • JAMES BROWN • MARVIN...

FIRST & SECOND LINE IN NEW ORLEANS, 1990-2005

THE STORY OF THE NEW ORLEANS JAZZ, BLUES, ZYDECO &...

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Junker's BluesChampion Jack DupreeJack Dupree Champion00:02:461941

-

2Two Wings Every Man's Got To Lay Down And DieRev Utah SmithTraditionnel00:03:151947

-

3Hey Little GirlProfessor LonghairProfessor Longhair00:03:071949

-

4Blues Stay Away From MeLonnie JohnsonAnton Delmore00:02:571949

-

5Her Mind Is GoneRoy Byrd And His Blues JumpersProfessor Longhair00:02:411950

-

6Hard Luck Blues Heartbreak HotelRoy Brown And His Mighty Mighty MenRoy-James Brown00:03:041950

-

7Four O' Clock Blues Heartbreak HotelLittle Mr MidnightEddie Durham00:02:501950

-

8Me And My Crazy SelfJohnson LonnieHenry Glover00:02:381951

-

9High Flying WomanDave BartholomewBartholomew Dave00:02:421951

-

10Lawdy Miss ClawdyPrice LloydLloyd Price00:02:311952

-

11I'm GoneShirley And Lee With Dave Bartholomew And OrchestraLeonard Lee00:02:201952

-

12Jimmie LeePrice LloydLloyd Price00:02:121952

-

13Two WingsRev Utah SmithTraditionnel00:02:551953

-

14Lucy Mae BluesLee Sims FrankieLee Sims Frankie00:02:331953

-

15Tend To Your Business BluesLittle Sonny JonesLittle Sonny Jones00:02:201954

-

16What's WrongSugar Boy And His Cane CuttersSugar Boy Crawford00:02:411954

-

17Down BoyPaul GaytenInconnu00:02:381954

-

18Reap What You SowGuitar SlimGuitar Slim00:02:411954

-

19Another MuleDave BartholomewDave Bartholomew00:02:281954

-

20Rich WomanLil Millet And His CreolesD. Labostrie00:02:391955

-

21Mack The KnifeLouis ArmstrongKurt Weill00:03:241955

-

22Just A Little While To Stay HereMahalia Jackson And The Falls Jones EnsembleTraditionnel00:03:461956

-

23Blue MondayFats DominoDave Bartholomew00:02:231955

-

24Got Love If You Want ItHarpo SlimHarpo Slim00:02:481957

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1I Got Sumpin' For YouGuitar SlimGuitar Slim00:02:401955

-

2I Hear You KnockingLewis SmileyKing Pearl00:02:331955

-

3Ain't Got No HomeHenry Clarence FrogmanJack Dupree Champion00:02:231956

-

4Baby, PleaseClifton ChenierTraditionnel00:02:291956

-

5I'M A King BeeHarpo SlimProfessor Longhair00:03:071957

-

6Just BecauseLarry WilliamsAnton Delmore00:02:491957

-

7My SoulClifton ChenierProfessor Longhair00:02:541957

-

8The DummyArt NevilleRoy-James Brown00:01:551957

-

9Flat Foot SamOscar WillsEddie Durham00:02:111957

-

10Bony MoronieLarry WilliamsHenry Glover00:02:461957

-

11Slow DownLarry WilliamsBartholomew Dave00:02:461957

-

12Dizzy Miss LizzieLarry WilliamsLloyd Price00:02:121957

-

13Zing ZingArt NevilleLeonard Lee00:02:031958

-

14I'm In LoveHenry Clarence FrogmanLloyd Price00:02:301958

-

15What's Going OnArt NevilleTraditionnel00:02:031958

-

16Don't You Just Know ItHuey SmithLee Sims Frankie00:02:341958

-

17Belle AmieArt NevilleLittle Sonny Jones00:02:201958

-

18Arabian Love CallArt NevilleSugar Boy Crawford00:02:261958

-

19ChicoA. ToussaintInconnu00:02:171959

-

20She Said “Yeah”Larry WilliamsGuitar Slim00:01:521958

-

21I'll Do AnythingEddie BoDave Bartholomew00:02:101959

-

22That Certain DoorEaglin' SnooksD. Labostrie00:03:171960

-

23I'm Just A Lucky So And SoLouis ArmstrongKurt Weill00:03:091961

-

24SaharaDr JohnTraditionnel00:02:171961

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Come On (Let The Good Times Roll)Earl KingDave Bartholomew00:04:241960

-

2Nobody Knows (The Trouble I've Seen)Eaglin' SnooksHarpo Slim00:02:151960

-

3My Baby's Got SoulLarry WilliamsGuitar Slim00:02:371959

-

4Cry OnIrma ThomasKing Pearl00:02:271961

-

5Warm DaddyEddie BoJack Dupree Champion00:02:061960

-

6C.C. RiderEaglin' SnooksTraditionnel00:03:021960

-

7It's RainingIrma ThomasProfessor Longhair00:02:071961

-

8People Gonna TalkDorsey LeeAnton Delmore00:02:341961

-

9Something You GotC. KennerProfessor Longhair00:02:531961

-

10I Did My PartIrma ThomasRoy-James Brown00:02:311961

-

11Down The Road Junco PartnerRoland StoneEddie Durham00:02:371962

-

12The JokeReggie HallHenry Glover00:02:301962

-

13Fortune TellerBenny SpellmanBartholomew Dave00:02:121962

-

14Hoodlum JoeLee DorseyLloyd Price00:01:471962

-

15Ruler Of My HeartIrma ThomasLeonard Lee00:02:501962

-

16Pain In My HeartAlvin RobinsonLloyd Price00:02:551961

-

17Baby I'm WiseEddie BoTraditionnel00:02:321961

-

18Oh RedAlvin RobinsonLee Sims Frankie00:01:561961

-

19Somebody Told YouIrma ThomasLittle Sonny Jones00:02:401962

-

20I'm Gonna Get You YetDanny WhiteSugar Boy Crawford00:02:131962

-

21Hittin' On NothingIrma ThomasInconnu00:02:231962

-

22All For OneWillie TeeGuitar Slim00:02:391961

-

23A Losing BattleJohnny AdamsDave Bartholomew00:02:521962

-

24Talk About LoveBenny SpellmanD. Labostrie00:02:341962

Roots of soul FA5633

New Orleans Roots

OF Soul

1941-1962

Irma Thomas, Dave Bartholomew,

Larry Williams, Allen Toussaint,

Eddie Bo, Art Neville, Fats Domino…

LA NOUVELLE-ORLÉANS

La péninsule de la Nouvelle-Orléans est située dans le delta du fleuve Mississippi. Elle est cernée par des marais et des lacs qui l’isolent du reste des États-Unis. On y ressent une forte proximité avec l’eau, le golfe du Mexique, la mer et les ouragans qui plusieurs fois ont détruit la ville. Construite sur la boue du delta, elle a été pendant des siècles l’escale portuaire, la porte d’accès au continent par le fleuve géant. Comme celui de Miami, son port reliait le continent à l’Amérique latine et au kaléïdoscope culturel des Antilles : archipel des Keys, Îles Vierges1, Cuba, Haïti2, Saint-Domingue3, la Jamaïque4… L’historien Ned Sublette a décrit la Nouvelle-Orléans comme « la capitale des Caraïbes » tant cette presqu’île a une culture insulaire spécifique aux îles de la région : mélange d’Amérindiens, d’Europe, d’Afrique et de vaudou créole. Entre Texas et Floride, entre Deep South et Antilles, la richesse musicale de la Louisiane a été très influente dans la construction du langage musical américain moderne et de la musique soul en particulier. Elle s’explique par l’histoire de son exceptionnel mélange culturel.

LES RACINES PROFONDES DE LA SOUL À LA NOUVELLE-ORLÉANS

Territoire indien Choctaw pendant des millénaires (et autres ethnies ou subdivisions choctaws : Houmas, Natchez, Creeks, Attakapas, etc.), la région a été colonisée par la France à partir de 1682 et la Nouvelle-Orléans fondée en 1718. Avec environ 7000 habitants français en 1762, elle fut cédée à l’Espagne à l’issue d’une guerre, la région à l’est du fleuve revenant à l’Angleterre l’année suivante ; Des milliers de captifs yorubas, ibos, ouolofs, mandingues, akans, ashantis (etc.) provenant des actuels Ghana, Togo, Sénégal, Bénin, Niger, Nigeria (etc.) ont été réduits en esclavage dans la région, apportant des cultures musicales variées. Dans certains cas, les apports culturels africains (dont la musique) étaient tolérés sur cette terre catholique, distincte de l’anglicanisme anglo-saxon en vigueur alentour, où les cultures africaines étaient strictement interdites. En 1785, 1600 Français acadiens expulsés du Canada par les Anglais ont débarqué dans le sud de la Nouvelle-Orléans, où on les appela les Cajuns ; En 1793-95, suite à l’abolition de l’esclavage par la révolution française ils ont été rejoints par des Français et Espagnols réfugiés de Saint-Domingue, accompagnés par leurs esclaves ouest africains. La tradition francophone est longtemps restée forte en Louisiane (comme en atteste ici Belle amie d’Art Neville) s’étiolant finalement à la fin du XXe siècle. Les Cajuns blancs francophones avaient leur musique propre et des artistes noirs proches d’eux (souvent des descendants de leurs esclaves ou employés) ont interprété le blues dans un esprit soul aux accents français — comme Clifton Chenier, roi du style noir zydeco5 mélangeant anglais et français, qui s’accompagne ici à l’accordéon, ou Fats Domino, dont la langue maternelle était le français. Plus tolérante avec les Afro-américains que le reste du continent, la Louisiane est redevenue française en 1800. En 1803 Napoléon Bonaparte l’a vendue aux États-Unis pour quinze millions de dollars après y avoir rétabli l’esclavage. Simultanément, lors de la révolution haïtienne vers 1804, de nombreux de planteurs francophones sont arrivés de Haïti avec leurs esclaves, apportant une culture vaudou qui comprenait des éléments bantous d’Afrique Centrale (Congo, Cameroun, Angola) en plus de ceux d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Un tel mélange n’existait nulle part ailleurs. Avec ses racines indiennes, sur lesquelles s’étaient greffées les Européens catholiques et anglicans d’au moins trois pays différents, des Africains animistes très variés et un assortiment de Caribéens déjà hybrides, la Nouvelle-Orléans a logiquement forgé une culture créole unique au monde — et des musiques à l’image de cette diversité, à l’inimitable personnalité. On trouve dans toutes les Caraïbes des musiques analogues au jazz6, mais c’est dans cette ville que ses principaux pionniers ont développé l’essentiel genre jazz, parmi lesquels le géant Louis Armstrong.

Très influent, le style soul (prononcer « saule » et non « sahole ») s’est matérialisé dans les années 1950, soit quatre-vingt dix ans après la guerre de sécession et l’abolition de l’esclavage. Elle a donc des racines (roots) très particulières, synthétisant différents éléments musicaux hérités de cette tragédie humaine : spirituals, blues, jazz, gospel. Comme pour le jazz et le blues, la région de la Nouvelle-Orléans a beaucoup contribué à cristalliser le style soul, un genre musical essentiel où les interprétations très senties, émouvantes de précurseurs comme Dave Bartholomew, Irma Thomas ou Roland Stone (qui était blanc), plongent leurs racines dans les chants d’esclaves, les negro spirituals. À l’exception de Benny Spellman, un Californien emblématique du style de la Nouvelle-Orléans où il a enregistré ses succès, les interprètes réunis ici (et la plupart des musiciens) sont tous originaires de cette ville ou de ses environs.

CONGO SQUARE

Un exemple d’ouverture aux musiques européennes est présent dans la version de Mack the Knife, un grand succès de Louis Armstrong en 1956. Cette « Complainte de Mackie » avait initialement été composée dans un style médiéval par un Juif allemand, Kurt Weill et l’écrivain allemand Bertolt Brecht pour leur Opéra de quat’ sous présenté à Berlin en 1928. Elle décrit un criminel incarné dans un personnage de requin cruel ; l’icône du jazz y a apporté un rythme utilisé par les artistes de gospel et une performance vocale marquée par le « scat », un style d’improvisation vocale dont il a été le pionnier et maître. En popularisant le scat, Armstrong a inspiré Ella Fitzgerald, Babs Gonzales ou encore Louis Prima, un célèbre interprète blanc de la Nouvelle Orléans (« I’m Just a Gigolo »). Cette fluidité, ce ressenti, cette émotion provoqués par des anacrouses (attaque de la note avant le temps), mélismes et autres ornementations mélodiques sont la substance même de la soul. La source de l’improvisation dans le jazz, et donc du scat, est à chercher du côté de la glossolalie, des sons de voix induits spontanément par la communication avec les esprits lors de transes prenant place lors des rituels animistes — ou leur dérivé chrétien, ici mis en évidence par les enregistrements de terrain du Reverend Utah Smith. Ces improvisations spirituelles se sont mutées jusque dans les fanfares du XXe siècle, lors du retour du cimetière où, par le truchement de leurs improvisations joyeuses, les musiciens relayaient les sentiments que leur évoquaient l’esprit du défunt. Les phénomènes de possession étaient présents dans les rites du « hoodoo » (vaudou américain) de jadis mais on les trouve encore dans certains temples protestants des États-Unis, ou par exemple chez les pentecôtistes de Jamaïque7.

Le dimanche à Congo Square — une vaste esplanade servant de place du marché au nord de la ville, y compris d’un important marché aux esclaves—, les Noirs étaient autorisés à jouer leurs musiques créoles, caribéennes, d’inspiration africaine : tambours, instruments à cordes, chants et danses débridées. Spécifique à la région de la Nouvelle-Orléans, cette tolérance aux musiques noires est devenue une attraction, un aspect pittoresque séduisant les visiteurs, les acheteurs et subissant des interdictions au fil du XIXe siècle. Bon an mal an la tradition et la légende de Congo Square se sont perpétuées jusqu’à nos jours. Congo Square est aujourd’hui un parc, un « lieu historique national » où trône une statue de Louis Armstrong. On peut lire ceci sur la plaque à l’entrée :

« Congo Square est situé près des lieux considérés sacrés et utilisés par les Indiens Houmas pour célébrer leur récolte annuelle du maïs bien avant l’arrivée des Français. Les réunions d’esclaves marchands à Congo Square ont commencé dès les années 1740 pendant la période coloniale française. Ce marché public a continué pendant la période espagnole. En 1803 Congo Square était célèbre pour ses rassemblements d’Africains en esclavage, qui jouaient des tambours, dansaient, chantaient et vendaient le dimanche après-midi. En 1819 ces réunions rassemblaient jusqu’à 500 ou 600 personnes. Parmi les danses les plus célèbres on compte la bamboula8, le calinda et le congo. Ces expressions culturelles africaines se sont graduellement développées jusqu’à devenir les traditions des Mardi Gras Indians, The Second Line et, en fin de compte, le jazz et le rhythm and blues de la Nouvelle-Orléans. »

Les esclaves venus des Caraïbes ont nourri la région de rythmes, percussions, chants et rituels de type animiste (vaudou). Ces rituels ont été principalement apportés par les esclaves haïtiens à partir de la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Beaucoup avaient séjourné à Cuba. Les Cubains noirs ont apporté des cultures analogues, aux racines ibo, akan, yoruba (santería, abakuà et orishas yorubas) et bantoues (Congo, Cameroun, etc.). La rumba cubaine a marqué les États-Unis et son tibois (clave en espagnol) est présent dans de nombreux titres de la Nouvelle-Orléans, comme dans l’emblématique « Mardi-Gras in New Orleans » de Professor Longhair9 en 1949 ou ici sur Arabian Love Call d’Art Neville, le futur fondateur des Meters, un groupe emblématique de la musique soul. On reconnaît aussi un rythme mambo marqué sur Rich Woman de Li’l Millett dont la mélodie et le riff de guitare rappellent aussi le « Mush Mouth Millie » de Bo Diddley10 (pour écouter d’autres influences cubaines sur la musique des États-Unis de cette époque, voir Cuba in America 1940-1962 dans cette collection). L’aspect rythmique des musiques afro-américaines et afro-caribéennes syncopées est traité dans le triple album Roots of Funk dans cette collection, où l’on retrouve plusieurs artistes majeurs de la région. Ce coffret Roots of Soul - New Orleans est en revanche orienté par un fil conducteur lié au style vocal propre à la soul — en l’occurrence celle de la Nouvelle-Orléans, qui a influencé les interprètes de soul dans tout le pays et bien au-delà.

NEGRO SPIRITUALS

Au fil du XIXe siècle et bien avant, en plus des chansons européennes qu’ils jouaient dans un cadre de divertissement (quadrille, schottische, valse, etc.) ou lors des défilés de Mardi Gras, les esclaves ont créé des chansons exprimant leur détresse mais aussi leurs espoirs, des chants simples mais rythmés et émouvants, puissamment évocateurs, appelés negro spirituals. Par leur présence à Congo Square, les chants et rituels animistes vaudou (Haïti) et afro-cubains ont joué un rôle dans la construction des negro spirituals de la région, qui étaient la principale forme d’expression des esclaves. Ceci les distingue vraisemblablement des spirituals d’autres régions, où toute évocation même ténue de l’animisme était réprimée par la loi. On retrouve d’abondantes traces de cette présence animiste, qui s’est affirmée et répandue sur tout le continent par le biais des émigrations au XXe siècle. Ce folklore hoodoo est décelable par un petit parcours initiatique dans le blues, le jazz, le rock et le calypso (lire le livret et écouter Voodoo in America 1926-1961 dans cette collection). L’auteur de « Jock-o-Mo » Sugar Boy Crawford y fait y largement allusion ici sur What’s Wrong :

J’ai un os de chat noir pendu au-dessus de ma porte

De la poudre de perlimpinpin saupoudrée sur mon sol

Je porte un crâne sur le côté

Si ça ne me porte pas bonheur je crois que je mérite de mourir

Avec le développement au XIXe siècle de temples méthodistes, baptistes, pentecôtistes (etc.) fréquentés par les Afro-américains, les spirituals d’esclaves ont peu à peu pris une tournure chrétienne en évoquant des mythes bibliques : notamment celui de Moïse et des Israëlites déportés en esclavage à Babylone par Nabuchodonosor II et leur retour à la terre promise de Sion. Les esclaves et leurs descendants s’identifiaient fortement à ces tribulations d’esclaves et ces métaphores bibliques exprimaient leur désir de libération de façon politiquement correcte. Les double-sens, et une discrète incitation à la fuite, y étaient courants. Les negro spirituals étaient bien distincts des cantiques (spirituals) interprétés dans les églises catholiques françaises, espagnoles et dans les temples anglicans/épiscopaux anglo-américains blancs11. On peut écouter ici le Reverend Utah Smith chantant deux negro spirituals surchauffés en s’accompagnant à la guitare électrique, dans un temple où les fidèles lui répondent et communient. Ces titres explicitent la ferveur vocale à la base de la soul, mais aussi l’influence essentielle de l’énergie spirituelle dans le rock, qui est lui aussi un héritage des spirituals. Two Wings (deux ailes) suggère un envol vers la liberté : vers l’Afrique, vers Sion — ou plus pragmatiquement vers le paradis. Ce thème est récurrent dans les spirituals. Dans ce prêche de 1947, Utah Smith apparaissait guitare électrique à la main, ampli à fond, affublé d’ailes d’ange de type carnaval. Dans une Louisiane violemment raciste, le révérend chantait cette aspiration à la liberté avec toute son âme. Née à la Nouvelle-Orléans où elle grandit avant d’émigrer à Chicago, l’extraordinaire Mahalia Jackson en fut l’une des plus grandes interprètes. Elle chante ici Just a Little While to Stay Here, un spiritual traditionnel, d’auteur inconnu, qui invite à la patience en attendant le paradis :

Bientôt cette vie sera terminée

Et notre pèlerinage s’achèvera

Bientôt nous commencerons notre voyage vers le ciel

Et nous serons à nouveau chez nous avec nos amis

MARDI GRAS

Les esclaves jouaient aussi des musiques européennes pour leur maîtres. Ils les enrichissaient de rythmes incitant à la danse, une pratique populaire pourtant proscrite par les chrétiens puritains blancs : seul l’âme pouvait élever l’âme vers Dieu. Le corps et donc la danse étaient considérés être des vecteurs éloignant les chrétiens du droit chemin. Cette fusion musicale afro-créole n’en était pas moins une réalité, incorporant valse, quadrille français, balades irlandaises (à la construction proche du blues), mélodies espagnoles, chansons populaires anglaises, chants de marins (etc.) aux chants animistes et matrices rythmiques venues des Caraïbes. Quelle qu’en soit la nature, la musique était un vecteur de libération pour les esclaves qui la jouaient comme pour les hommes libres de couleur, qui subissaient également l’oppression de la société coloniale. Certains avaient rejoint les Indiens eux aussi martyrisés, et les métissages se multipliaient. Les descendants de ce métissage défilent depuis lors des carnavals de la Nouvelle-Orléans sous le nom des Mardi Gras Indians. L’un d’entre eux, Willie Tee, ici à ses débuts sur All For One, deviendrait l’un des musiciens des Wild Magnolias, un célèbre groupe de funk composé de Mardi Gras Indians.

Le temps d’une chanson, d’une danse libre, les opprimés reprenaient le contrôle de leur corps devenu outil de production, se réappropriaient ainsi leur esprit — et leur âme (soul). Lors des défilés de Mardi Gras ou dans les fanfares lors d’obsèques, la musique aux racines du jazz retentissait au début du XXe siècle. Les musiciens jouaient dans des cabarets, restaurants, des hôtels et parfois même des bordels. Le jazz et ses improvisations sont, sous différentes formes, une culture propre à toutes les Caraïbes12. En revanche le blues est une forme spécifique prise par la musique afro-américaine du sud des États-Unis.

BLUES

Vers 1890 (et probablement plus tôt) le blues était déjà répandu dans la région du delta du Mississippi. Bien qu’influencé par des structures harmoniques très simples comme celles des cantiques catholiques et des balades irlandaises, il était fondamentalement un prolongement des negro spirituals d’essence africaine. Comme la soul un demi-siècle plus tard, le blues plongeait ses racines dans le langage musical des spirituals chantés partout par les fidèles dans les temples baptistes, pentecôtistes, méthodistes, mais il exprimait souvent des histoires plus triviales. Il imprègne toute la musique de la région : jazz, musique soul, zydeco des Noirs francophones comme Clifton Chenier, influençant jusqu’à la musique cajun francophone pourtant assez fermée aux influences « noires »13. Certains artistes de blues travaillant en ville jouaient du piano. Ils sont les véritables grand-pères de la soul, musique urbaine et profane, comme ici Champion Jack Dupree interprétant Junker’s Blues, chanson sœur de « Junco Partner ». La tradition pianistique de la Nouvelle-Orléans a également accouché de Professor Longhair, un autre pianiste de blues très influent qui chantait lui aussi du rock/rhythm and blues dans un style personnel. Son style a profondément marqué les pianistes de génération suivante dont Salvador Doucette, Fats Domino, Huey « Piano » Smith et les grands pianistes arrangeurs de la soul comme James Booker qui mélangeait virtuosité et blues, Art Neville, Allen Toussaint, Eddie Bo et Dr. John (dont on peut écouter ici le premier enregistrement au piano, Sahara). Blanc comme ce dernier, Roland Stone chante ici une version de « Junco Partner » sous le nom de Down the Road. Il en existe nombre d’enregistrements14 (dont une version reggae gravée en 1980 par The Clash) ; la mélodie de « The Fat Man », premier rock de Fats Domino en 1949, est basée dessus. Ce titre traditionnel local évoque explicitement les stupéfiants. Il était chanté dans les durs pénitenciers du sud, qui prolongeaient le système d’exploitation des esclaves sur les lieux mêmes des anciennes plantations.

Tout aussi influents, les bluesmen itinérants s’accompagnaient souvent à l’harmonica, comme ici Slim Harpo, dont le I’m a King Bee fut repris par les Rolling Stones pour ouvrir leur premier album en avril 1964 (et dont le Got Love If You Want It a été enregistré par les Kinks débutants à la même époque). Lonnie Johnson, un virtuose de la guitare, chante ici le classique Blues Stay Away From Me, qui sera magnifiquement repris par les Delmore Brothers (country) en 1949 et par Gene Vincent en 1956. Son chant plaintif et émouvant (Me and my Crazy Self) annonce le style soul.

Nombre de chanteurs-guitaristes solistes significatifs ont surgi dans la région de la Nouvelle-Orléans et dans l’état voisin du Mississippi. Ils ont tous joué du blues : Frankie Lee Sims, Guitar Slim, Sugar Boy Crawford, Snooks Eaglin et Earl King, dont le Come On a été rendu célèbre par Jimi Hendrix, qui dix ans plus tard en a inclus une version sur son chef-d’œuvre Electric Ladyland. Un grand nombre d’artistes de blues ont ainsi appris à chanter très jeunes dans les cérémonies religieuses du dimanche. Ce fut par exemple le cas de Shirley Goodman (Shirley and Lee), qui fut une véritable pionnière du style soul avec son irrésistible interprétation de son premier succès, I’m Gone, à l’âge de seize ans à peine. Le Reverend Utah Smith chante ici le gospel Every Man Got to Lay Down and Die de Sister Ola Mae Terrel (qui comme lui s’accompagnait à la guitare électrique) avec des accents qui évoquent fortement le rock le plus excité.

GOSPEL

À partir des années 1930, des chansons populaires de nature religieuse ont été composées, puis interprétées lors de rites chrétiens dans tout le pays, donnant naissance au gospel noir, un nouveau genre renouvelant les vieux negro spirituals. Associé à l’alcool, à la marijuana, à la vie dissolue, le blues était très mal vu par une partie de la population. Avec l’apparition des gospel songs, et afin de ne rater aucune opportunité de trouver un engagement — ou une pièce de monnaie — beaucoup de bluesmen connaissaient souvent un répertoire sacré (spirituals, gospel) et un autre profane (blues, chansons populaires) mais leur style musical spontané variait peu d’une tendance à l’autre (les guitar evangelists).

Dans la tradition écrite européenne, on tergiversait avec sophistication et subtilité sur l’interprétation idéale qu’il convenait d’apporter à des compositions de musiciens souvent disparus ; Ses plus populaires interprètes, parmi lesquels l’exceptionnelle Maria Callas ou l’Afro-américain Paul Robeson comptent parmi ceux qui ont osé apporter une personnalité forte, qui leur était propre. La tradition afro-américaine des spirituals et du gospel allait bien plus loin en ce sens, incitant à la spontanéité, au ressenti, à l’originalité au point de prendre de grandes libertés avec la mélodie, l’arrangement, le tempo, les paroles. Cette musique sacrée suggérait la liberté par sa liberté d’expression musicale et par l’épanouissement de la personnalité qui, après tout, était un don de Dieu. Comme le blues, les spirituals et le gospel se sont métamorphosés dans les années 1950. Ils ont donné naissance à un style profane incitant à la danse, où les sentiments amoureux se sont substitués aux thèmes chrétiens. L’intensité des interprétations et la panoplie stylistique des spirituals était utilisée dans le blues et le jazz du début du siècle. À sont tour, le gospel a imprégné la sensibilité d’immenses interprètes comme Billie Holiday ou Dinah Washington, puis il a perduré dans le rock/rhythm and blues, deux termes qui désignent la même musique (voir le coffret Race Records 1942-1955 - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U. S. Radio, FA 5600). Ce processus de mutation du gospel et du blues vers la soul est montré et expliqué en détail dans le complémentaire triple album Roots of Soul dans cette collection ; Avec des chanteurs importants comme Louis Armstrong ou Jack Teagarden, la Nouvelle-Orléans a fourni toute une école d’interprètes qui devinrent des artistes classés « soul ». L’ambiance dramatique, transmettant des émotions, créée par ces interprétations très senties, est l’héritage, la substance et l’âme de la musique soul. On retrouve autant cette tension particulière dans la voix de Louis Armstrong, figure tutélaire de toute l’Amérique noire, que dans les premiers classiques de pure soul comme ici A Losing Battle de Johnny Adams ou Hitting on Nothing d’Irma Thomas en 1962. Le gospel a ouvert la porte à l’émotion dans la musique populaire américaine. Il a encouragé toutes les impulsions, toutes les inspirations, comme le montre ici le chant intuitif et spontané de la reine du genre, Mahalia Jackson.

ROCK AND ROLL

La musique soul descend des spirituals, du gospel, du blues, du jazz — mais peut-être descend-elle plus directement encore du rock, un style qui a lui-même catalysé ces quatre genres fondateurs. Les plus grands noms de la soul y ont excellé, de James Brown à Otis Redding, de Art Neville à Little Richard, qui enregistra presque tous ses classiques du rock dans le studio de Cosimo Matassa à la Nouvelle-Orléans avec le groupe de Dave Bartholomew15. Après la retraite religieuse de Little Richard fin 1957, Larry Williams lui a succédé chez Specialty. Pianiste comme lui, il enregistra avec les mêmes musiciens, dans le même studio et dans le même style : rock pur mais aussi ballades soul. Tout comme le rock Bonie Moronie, son « slow » Just Because a été repris en 1975 par John Lennon dans son célèbre album Rock ‘n’ Roll. L’excellent Larry Williams a beaucoup marqué les Beatles, qui ont enregistré ses compositions Bad Boy, Dizzy Miss Lizzie et Slow Down, toutes chantées par Lennon. En enregistrant She Said « Yeah » les Rolling Stones ont eux aussi propulsé une création de Larry Williams dans la culture générale des années 1960, comme ils l’ont fait pour Rain in my Heart d’Irma Thomas (également créatrice de « Time Is on my Side »), Fortune Teller de Benny Spellman et I’m a King Bee de Slim Harpo.

Roy Brown était initialement un chanteur de gospel ; comme Little Richard et James Brown après lui, il s’est reconverti dans le blues et le rock. Il a influencé Elvis Presley, qui a fait de sa composition « Good Rockin’ Tonight » un de ses premiers succès chez Sun en 1954. Roy Brown interprète ici l’obscur Hard Luck Blues (1950) dont la mélodie a été plagiée par Mae Boren Axton et Tommy Durden, les auteurs de « Heartbreak Hotel » — sans doute le morceau le plus célèbre d’Elvis. Bien des éléments de « Heartbreak Hotel » (1956) rappellent les stéréotypes de la soul : son thème, son pathos, son tempo lent, l’arrangement, ses ornementations et variations d’intensité vocale… Elvis Presley, qui avait vu Roy Brown sur scène, n’a pas été le seul à s’inspirer de ce morceau emblématique de son style, puisque le Four O’Clock Blues de Little Midnight y ressemble encore plus — mais cinq ans avant « Heartbreak Hotel ».

SOUL

La soul pourrait être définie par l’intensité de ses interprétations vocales, dans l’émotion qu’elles transmettent dans le cadre de ses codes divers, héritage des cultures afro-américaines.

Ces émotions sont le plus souvent poignantes, comme ici dans de nombreux blues (Lonnie Johnson, Little Sonny Jones, Guitar Slim, etc.) ou chez le fantastique Snooks Eaglin, un guitariste chanteur aveugle et versatile influencé par Ray Charles ; elles peuvent être pleines de ferveur dans les spirituals d’Utah Smith ; gaies comme ici chez Louis Armstrong ou même humoristiques comme en témoigne Clarence Frogman » Henry ou Huey « Piano Smith. À vrai dire, ces étiquettes superficielles « blues », « jazz », « soul », « rhythm and blues » ou « rock » ne peuvent pas être accolées à tel ou tel interprète puisque la plupart d’entre eux ont tour à tour chanté dans ces styles interconnectés. Ils les ont mélangés dans les clubs de Louisiane, dans l’unique studio de la ville — et bien souvent accompagnés par les mêmes musiciens, ceux de la nébuleuse réunie autour de Dave Bartholomew.

Né en 1918, Dave Bartholomew avait étudié la trompette avec Peter Davis, le professeur de Louis Armstrong. Il est devenu professionnel dans quelques orchestres de jazz et après avoir joué dans un orchestre militaire pendant la guerre, en 1947 il a monté un groupe que le musicologue Robert Palmer décrit comme « le modèle pour tous les premiers groupes de rock du monde entier ». Ils ont joué deux ans, diffusant une émission de radio dans la région à partir du magasin de Cosimo Matassa, établissant une excellente réputation locale. Bartholomew a consolidé sa formation avec quelques-uns des meilleurs musiciens de la ville, qu’il emprunta en bonne partie à son concurrent de Paul Gayten, dont le groupe était déjà réputé. Parmi eux, l’essentiel batteur Earl Palmer, l’un des plus importants batteur de l’histoire du rock, pionnier de l’utilisation, de l’emphase du backbeat dans le rock (on retrouvait déjà le backbeat, accent sur les temps 2 et 4, dans « Backbeat Boogie » de Harry James en 1939 et d’autres titres de jazz/blues), Earl Palmer avait étudié la musique et savait la lire et l’écrire. Dave Bartholomew est devenu le directeur artistique des disques Imperial, pour qui il a gravé un premier disque dans le studio J&M de Cosimo Matassa en 1947. Le bassiste Frank Fields, le guitariste Earl McLean et les saxophonistes Clarence Hall, Joe Harris et Red Tyler étaient déjà là lors des enregistrements dans le rudimentaire studio de Matassa en 1949, tout comme les pianistes Salvador Doucette et Fats Domino, qui devint aussitôt un phénomène, vendant des dizaines de millions de disques dès le début des années 1950. Puis les saxes de Lee Allen, Herb Hardesty, Plas Johnson et d’autres ont rejoint le cénacle, consolidant l’équipe numéro un de l’écurie, rejointe par d’autres cracks comme Harold Battiste ou Roy Montrell (voir discographie). Petit, rudimentaire, situé dans l’arrière boutique des parents de Matassa à Rampart Street, J&M fut le premier studio digne de ce nom à la Nouvelle-Orléans. Une bonne partie de ce coffret a été enregistrée dans ce lieu légendaire où de grands classiques de Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Little Richard16 et des centaines d’autres ont été capturés avec l’équipe de Bartholomew. Professionnel et organisé, le trompettiste est devenu à la fin des années 1940 le producteur, arrangeur et compositeur le plus important d’une ville où la musique était partout. Quittant Imperial en 1950, il a travaillé avec d’autres marques, dont Specialty (pour Little Richard, puis Larry Williams), Decca et King. Brillant chanteur précurseur de la soul comme on peut l’écouter ici sur High Flying Woman et Another Mule, il était également capable de produire les meilleurs accompagnements et arrangements de rock, comme ici avec Art Neville et Larry Williams. Dave Bartholomew excellait dans le blues mais composait aussi des chansons aux mélodies plus ambitieuses, annonçant déjà le style qu’au début des années 1960 on appellerait la soul music. Il a écrit et produit les plus grands succès de Fats Domino dans cette veine, dont les classiques Blue Monday et I Hear You Knocking de Smiley Lewis. On lui doit aussi I’m Gone, premier succès de Shirley and Lee. Styliste majeur du rock, il a ainsi été de surcroit un contributeur essentiel à la naissance de la soul. Sa collaboration avec Fats Domino a fait des deux collaborateurs les deuxièmes plus gros vendeur de disques (65 millions au total) de l’époque derrière Presley.

Ses musiciens ont ensuite continué à travailler avec différents arrangeurs. On les retrouve tout au long de cet album. Cosimo Matassa a ouvert un nouveau studio et un son 100% soul s’est progressivement imposé. Des pianistes comme Doucette, Allen Toussaint et Art Neville ont renouvelé la tradition des pianistes-arrangeurs de la ville, créant des styles originaux copiés depuis dans tout le pays et au-delà. Ils comptent parmi les pionniers historiques de la soul comme du funk, qui se développeront de Memphis à Atlanta, à Los Angeles, New York ou Detroit. Après quelques séances à la guitare, Mac Rebennack (Dr. John) a été entièrement adopté par l’équipe numéro un du studio vers 1960. Il est un cas atypique d’un musicien blanc dans cette culture noire — comme ici Roland Stone, « le plus soul des chanteurs blancs » ou Johnny Winter au proche Texas. De grands interprètes de musique « soul » (utilisant des suites harmoniques de plus en plus démarquées du blues et des bases du gospel) ont abondé dès la fin des années 1950, mais le terme « soul » n’a pris son envol qu’en 1963 environ. La crème de ces artistes associés au son de la Nouvelle-Orléans est réunie ici : Reggie Hall, Eddie Bo, Snooks Eaglin, Johnny Adams, Willie Tee, John « Scarface » Williams — le chanteur de Huey Smith’s Clowns (sous le nom des Tick Tocks) qui était chef d’une tribu des Mardi Gras Indians, The Apache Hunters — et la reine de la soul de la Nouvelle-Orléans Irma Thomas comptent parmi les pionniers de ce genre musical. La richesse de l’âge d’or du rhythm and blues de la ville rend impossible l’inclusion de tous les titres qui mériteraient de figurer dans ce florilège, comme par exemple le « Mother in Law » d’Ernest K-Doe ou tant d’autres enregistrés par les artistes représentés ici. Mais des racines spirituals au blues, du jazz au gospel jusqu’à la soul pure, la naissance et le cheminement de l’influent style soul de la région sont ici explicités.

Bruno Blum, décembre 2015.

Merci à Dale Blade, Augustin Bondoux, Jon Cleary, Jean-Michel Colin, Stéphane Colin, Gilles Conte, Daniel Gondol/Le Jockomo, Gary Karp, Gilles Pétard, Gilbert Shelton, Nicolas Teurnier/Soul Bag et Michel Tourte.

© 2016 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1. Lire le livret et écouter Virgin Islands Quelbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) dans cette collection.

2. Lire le livret et écouter Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615) dans cette collection.

3. Lire le livret et écouter Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450) dans cette collection.

4. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275) dans cette collection.

5. Lire le livret et écouter Zydeco - Black Creole, French Music and Blues 1929-1972 (FA 5616) dans cette collection.

6. Lire le livret et écouter Jamaica - Jazz 1931-1962 à paraitre dans cette collection et Swing Caraïbe - Premiers jazzmen antillais à Paris 1929-1946 (FA 069) dans cette collection.

7. Lire les livrets et écouter Haiti Vodou - Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (FA 5626) et Jamaica Folk Trance Possession - Roots of Rastafari 1939-1961 (FA 5384) dans cette collection.

8. Écouter « Baboule Dance » dans Haiti Vodou - Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (FA 5626) et « Bamboula » dans Slavery in America - Redemption Songs1914-1972 (FA 5647) dans cette collection.

9. Lire le livret et écouter Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498) dans cette collection.

10. Voir les deux triple albums The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 et FA 5406) dans cette collection.

11. Lire les livrets et écouter Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA 5467) et Gospel Volume 1 - Negro Spirituals and Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA 008) dans cette collection.

12. Lire les livrets et écouter Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 à paraitre dans cette collection et Swing Caraïbe 1929-1946 (FA 069) dans cette collection.

13. Lire les livrets et écouter Cajun - Louisiane 1928 - 1939 (FA 019) dans cette collection.

14. La version de James Wee Willie Wayne qui popularisa ce morceau en 1951 est incluse sur Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415) dans cette collection.

15. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607) dans cette collection.

16. Lire le livret et écouter The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607) dans cette collection.

Roots of Soul

New Orleans 1941-1962

Irma Thomas, Dave Bartholomew, Larry Williams, Eddie Bo, Allen Toussaint, Art Neville…

NEW ORLEANS

The New Orleans peninsula lies in the Mississippi River delta, surrounded by marshland and lakes that isolate it from the rest of The United States. One can feel the closeness of water, the Gulf of Me-xico, the sea and the hurricanes that have destroyed the city several times. Built on the mud of the delta, the city itself has been a stopover port for centuries, providing access to the continent via this giant river. Like that of Miami, the Port of New Orleans links the mainland with Latin America and the cultural kaleidoscope of the Caribbean: the archipelago of the Keys, the Virgin Islands1, Cuba, Haiti2, the Dominican Republic3, Jamaica4… Historian Ned Sublette described New Orleans as “the capital of the Caribbean”, because the peninsula’s insular culture was so specifically regional, combining a mix of Amerindian, European, African and Creole Voodoo traditions. From Texas to Florida and from the Deep South to the Antilles, the musical richness of Louisiana has been extremely influential in the constructing of a modern American music language, and soul music in particular. All of which can be explained by the history of its exceptional cultural mix.

THE DEEP ROOTS OF NEW ORLEANS SOUL

For thousands of years the region was a Choctaw Indian territory (including other Choctaw ethnic groups and subdivisions, like the Houma people, the Creeks and the Natchez and Atakapa Indians etc.) France colonized the region beginning in 1682 and founded New Orleans in 1718. By 1762 it numbered some 7000 French inhabitants and was made over to Spain after a war, with the region to the east of the river becoming English territory the following year. Thousands of captives — Yoruba, Ibo, Wolof, Mandingo, Akan, Ashanti etc. — coming from today’s Ghana, Togo, Senegal, Benin, Niger, Nigeria and others were reduced into slavery, and they brought varied musical cultures to the area. In some cases, African cultural contributions (including music) were tolerated in this Catholic territory distinct from the Anglican religion practised by Anglo-Saxons in surrounding areas, where African cultures were strictly forbidden.

In 1785, the English expelled some 1600 French Acadians from Canada; they were to disembark south of New Orleans, where they were known as “Cajuns”. In 1793-‘95, after the abolition of slavery following the French Revolution, the Cajuns were joined by French and Spanish refugees from what was then known as Saint-Domingue, accompanied by their own West African slaves. French-speaking traditions remained strong in Louisiana for a long time (as shown here by Art Neville’s Belle amie) finally declining towards the end of the 20th century. French-speaking white Cajuns had their own music, and black artists who were close to them (often descendants of their slaves or employees) sang blues songs in a soul vein with French accents, like Clifton Chenier — the King of the black zydeco5 style combining English and French, here accompanying himself on the accordion — or Fats Domino, whose mother tongue was French.

Louisiana was more tolerant of Afro-Americans than the rest of the continent, and became French again in 1800. Three years later, Napoleon Bonaparte sold it to The United States for fifteen million dollars after reinstating slavery there. Simultaneously, during the Haitian Revolution in around 1804, many of French-speaking planters arrived from Haiti with their slaves, bringing with them a voodoo culture that included Bantu elements from Central Africa (The Congo, Cameroon, Angola) in addition to those of West Africa. A mixture of this kind was unique. It existed nowhere else, and with its Indian roots — plus grafts of Catholic and Anglican Europeans from at least three different countries, plus widely varying African animists and an assortment of Caribbean influences that were already hybrids —, New Orleans logically forged a Creole culture that was unique —, not to mention music with an inimitable personality that reflected this diversity. Music similar to jazz can be found throughout the Caribbean6, but is was principally in New Orleans that its main pioneers, among them the giant Louis Armstrong, developed the essentials of the jazz genre.

Highly influential, the soul style materialized in the Fifties, i.e. some ninety years after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. So its roots are therefore very precise, and they synthesize musical elements inherited from that human tragedy: spirituals, blues, jazz, gospel. As for blues and jazz, the New Orleans area contributed greatly to crystallize the soul style, an essential music genre where the deeply moving performances of precursors like Dave Bartholomew, Irma Thomas or Roland Stone (who was White), had roots lying deep in the negro spirituals that put words into the songs of slaves. Except for Benny Spellman, whose Californian style was an emblem of the New Orleans style in which he recorded his hits, the performers featured here (and most of the musicians) all came from this city and its environs.

CONGO SQUARE

An example of the genre’s openness towards European music is present in this version of Mack the Knife, a great Louis Armstrong hit in 1956. Originally written in medieval style (as the “Murderous Deed of Mackie Messer”) by two Germans, the Jewish composer Kurt Weill and lyricist/writer Bertolt Brecht, the song was part of their Threepenny Opera premiered in 1928 in Berlin, and it portrayed a criminal as a cruel shark. In Armstrong’s version, the trumpeter/singer, a jazz icon, gave the song a rhythm used by gospel artists, and his vocal performance was marked by his “scat” singing; he pioneered this style of vocal improvisation of which he was a master. In popularizing scat, Armstrong gave inspiration to Ella Fitzgerald, Babs Gonzales and others (like Louis Prima, the famous white performer from New Orleans who sang “I’m Just a Gigolo”.) The fluidity, feeling and emotion provoked by the singer’s anacrusis, (in attacking the note before the beat), melisma and other melodic ornamentation are the very substance of soul.

The source of improvisation in jazz, and therefore scat, can be sought in glossolalia, those vocal sounds spontaneously induced during («speaking in tongues»), communication with the spirits in trances that took hold of those participating in animist rituals — or their Christian derivative, here evidenced in field recordings made by The Reverend Utah Smith. These spiritual improvisations were even transferred into 20th century brass bands: in parades on their return from cemeteries, the musicians’ cheerful improvisations would relay feelings that the spirits of the deceased called up inside them. Phenomena of possession were present in “hoodoo” (or American voodoo) rituals of bygone days, but they can still be found in some Protestant places of worship in the United States, or among Jamaican Pentecostalists for example.7

On Sundays in New Orleans’ Congo Square — a vast esplanade used as a marketplace in the north of the city, and also a market for slaves — Black people were allowed to play their own Creole and Caribbean music of African inspiration: drums and stringed instruments orchestrated unbridled dances and songs. This tolerance of Black music was specific to the region surrounding New Orleans, and it became an attraction, a picturesque aspect that seduced visitors and buyers, but it was progressively banned in the course of the 19th century. Year in, year out, the traditions and legends of Congo Square have been perpetuated right up to the present day.

Congo Square is a park nowadays, a “national historic place” with an imposing statue of Louis Armstrong. The plaque at the entrance reads: “Congo Square is in the “vicinity” of a spot which Houmas Indians used before the arrival of the French for celebrating their annual corn harvest, and was considered sacred ground. The gathering of enslaved African vendors in Congo Square originated as early as the late 1740’s during Louisiana’s French colonial period and continued during the Spanish colonial era as one of the city’s public markets. By 1803 Congo Square had become famous for the gathering of enslaved Africans who drummed, danced, sang and traded on Sunday afternoons. By 1819, these gatherings numbered as many as 500 to 600 people. Among the most famous dances were the Bamboula, the Calinda and the Congo. These African cultural expressions gradually developed into Mardi Gras Indian traditions, the Second Line and eventually New Orleans jazz and rhythm and blues.”

Slaves coming from the Caribbean spread their rhythms, percussion, chants and animist/voodoo rituals across the region. Principally Haitian, these slaves brought in their rites from the end of the 18th century onwards, and many had come via Cuba. With black Cubans arrived similar cultures whose roots lay in the Ibo, Akan, Yoruba peoples (with santería, abakuà and Yoruba orishas), and among Bantus from the Congo and the Cameroon, etc. The Cuban rumba made its mark on the USA and its tibois (or clave in Spanish) is present in numerous New Orleans titles like the emblematic Mardi-Gras in New Orleans from Professor Longhair8 in 1949, or as here in Art Neville’s Arabian Love Call (Art later founded The Meters, an emblem in soul music.) You can also recognize the marked mambo rhythm on Rich Woman by Li’l Millett, where the melody and guitar riff also remind you of Bo Diddley’s “Mush Mouth Millie9.” (for more Cuban influence on U.S. music of the time, see Cuba in America 1940-1962 in this series). The Frémeaux triple album Roots of Funk 1947-1962 in this same series deals with the rhythmical aspects of Afro-American and Afro-Caribbean syncopated music, with examples from several major artists of the region. This present set, however, has an approach based on the vocal style proper to soul music — that of New Orleans to be precise — which influenced soul performers throughout the country and indeed way beyond that.

NEGRO SPIRITUALS

In the course of the 19th century and even well beforehand, slaves, in addition to the European songs they played either for entertainment (quadrilles, Scottish country dances, waltzes etc.) or to accompany Mardi Gras parades, created their own songs as expressions of, not only misery, but also their own hopes; they were simple melodies but they had rhythm and emotion, and they were powerfully evocative: they called them Negro spirituals. Through their presence in Congo Square, animist songs and rituals from Haiti (voodoo) and the Afro-Caribbean region likely played a role in the construction of local Negro spirituals, which were the slaves’ principal form of expression. This is probably what differentiates them from the spirituals of other regions, where the law punished even a tenuous connection with animism. There are abundant traces of animism’s presence; it became stronger and spread throughout the continent with 20th century immigration. This hoodoo folk tradition is perceptible in a little initiatory journey through blues, jazz, rock and calypso (cf. Frémeaux’s Voodoo in America 1926-1961). “Jock-o-Mo” songwriter Sugar Boy Crawford makes open reference to that here in What’s Wrong:

Got a black cat bone hanging over my front door

Got some goofer dust sprinkled on my floor

Got a skeleton head I wear ‘round my side

If that don’t bring good luck I think I need to die.

With the 19th century development of Methodist, Baptist and Pentecostal temples and other places of worship with Afro-American congregations, the spirituals of the slaves gradually took on a Christian turn in evoking the myths of the Bible: notably the story of Moses and the Israelites deported to Babylon as slaves by Nebuchadnezzar II, and their return to the Promised Land of Zion. The slaves and their descendants identified strongly with such trials and tribulations, and those biblical metaphors expressed their desire for freedom in ways that were “politically correct.” Double-entendres, not to mention discreet invitations to flee, were common among them. Negro spirituals were quite distinct from the canticles (spirituals) sung in the Catholic churches of the French or Spanish, and in the Anglican or Episcopalian churches of white Anglo-American Protestants.10

Here you can listen to Reverend Utah Smith singing two heated Negro spirituals, accompanying himself on electric guitar in a church where the faithful respond to him and take communion. Vocal fervour is the basis of soul music and these titles make this explicit; but they also show the essential influence of the spiritual energy to be found in rock, which is also a legacy of those spirituals. “Two Wings” suggests flight to freedom: to Africa, to Zion — or, more pragmatically, to Paradise. The theme is recurrent in spirituals. In this sermon dating from 1947, Utah Smith appeared in front of his congregation holding an electric guitar… and also wearing the wings of a carnival-type angel. In such a violently racist Louisiana, the Reverend would sing of this longing for freedom with all his soul.

Born in New Orleans, where she grew up before emigrating (to Chicago), the extraordinary Mahalia Jackson was one of the genre’s greatest artists. Here she sings “Just a Little While to Stay Here”, a traditional spiritual by an anonymous writer which invites listeners to be patient while waiting to enter Paradise:

Soon this life will all be over

And our pilgrimage will end

Soon we’ll take our heavenly journey

Yeah, and be at home with friends again.

MARDI GRAS

Slaves also played European music for their masters, embellishing it with rhythms that encouraged dancing, a practice that was popular even though banned by white Christian puritans: only the soul could raise the soul up to God. The body, and therefore dancing, was considered a medium that led Christians away from the straight and narrow. This Afro-Creole musical fusion was no less real for all that, and it incor-porated waltzes, French quadrilles, Irish ballads (whose construction was close to blues), Spanish airs, English popular songs and sea shanties etc. along with animist songs and rhythmical modes coming from the Caribbean. Whatever its nature, music was a vector for freedom, both for the slaves who played it and for free men of colour, who were also subjected to oppression in a colonial society. Some had joined the Indians, who were also made to suffer, and the mixing of cultures grew. Ever since, the descendants of this mingled culture have paraded at the Carnivals of New Orleans as the Mardi Gras Indians. One of them, Willie Tee, here in his early years on All For One, would join the Wild Magnolias, a celebrated funk group made up of Mardi Gras Indians.

In the time it took for a song, or a free dance, the oppressed regained control of their body after it had become a production tool, thereby re-appropriating their spirit — and their soul. In Mardi Gras parades or in brass bands at funerals, music with jazz roots rang out at the beginning of the 20th century. Musicians played in clubs, restaurants and hotels, sometimes even in brothels. Under different forms, jazz and its improvisations represented a culture on its own throughout the Caribbean.11 The blues, on the other hand, was a specific form taken up by Afro-American music in the south of The United States.

BLUES

In around 1890 (and probably earlier), blues was already widespread in the Mississippi Delta region. Even though influenced by very simple harmonic structures such as those found in Catholic canticles and Irish ballads, blues was fundamentally

an extension of Negro spirituals, whose essence was African. Like soul a half-century later, blues had roots in the music language of spirituals that were sung everywhere by the faithful congregated inside Baptist, Pentecostal and Methodist churches, but it often expressed more trivial stories. It impregnated the music of the entire region: jazz, soul music,

the zydeco of black French-speakers like Clifton Chenier, and even spread to the music of French-speaking Cajuns, despite the fact their community was quite closed to “black” influence.12

Some blues artists who worked in the towns were piano-players, and these were the true grandfathers of soul, a secular, urban music form, like Champion Jack Dupree here playing Junker’s Blues, a sister-song to “Junco Partner.” The New Orleans’ piano tradition also gave birth to Professor Longhair, another very influential blues pianist, who also sang rock/R&B in a style all of his own that marked pianists of the subsequent generation — Salvador Doucette, Fats Domino, Huey “Piano” Smith — and the great arranger/pianists of soul music — like James Booker (who mixed virtuosity with the blues), Art Neville, Allen Toussaint, Eddie Bo and Dr. John (whose first piano recording, Sahara, you can listen to here.) Roland Stone, a white musician like the latter, here sings a version of “Junco Partner” under the name of Down the Road. There are numerous recordings of the latter in existence,13 (including a reggae version by The Clash cut in 1980); it forms the basis of the melody from “The Fat Man”, Fats Domino’s first rock title in 1949. This local (traditional) title has explicit references to drugs; it was sung in the tough penitentiaries of the South, which perpetuated the system of slave-exploitation in the very same places as the old plantations.

Equally influential were the itinerant bluesmen who often accompanied themselves on harmonica, like Slim Harpo here, whose I’m a King Bee was picked up by The Rolling Stones to open their first album in April ’64 (and whose Got Love If You Want It was recorded by The Kinks as beginners in that same period). Lonnie Johnson, a guitar virtuoso, here sings the classic Blues Stay Away From Me that country artists The Delmore Brothers would take up magnificently in 1949 (followed by Gene Vincent in 1956.) His plaintive, moving voice (Me and my Crazy Self) heralded the soul style.

A number of significant solo singer/guitarists came from around New Orleans and in neighbouring Mississippi. All played the blues: Frankie Lee Sims, Guitar Slim, Sugar Boy Crawford, Snooks Eaglin, Earl King, whose Come On was made famous by Jimi Hendrix (with yet another version ten years later on his Electric Ladyland masterpiece.) A great many blues artists learned to sing in church services while they were still young. Shirley Goodman (Shirley and Lee), for example, was barely sixteen when she gave her first hit I’m Gone an irresistible performance — a true pioneer of the soul style. The Reverend Utah Smith here sings the gospel Every Man Got to Lay Down and Die by Sister Ola Mae Terrel (like her, he accompanies himself on electric guitar) with accents strongly reminiscent of the most exciting rock.

GOSPEL

Beginning in the 1930’s, popular songs that were religious in nature were written and performed in Christian ceremonies throughout the country, giving birth to Black gospel, a new genre that revitalized the old Negro spiritual. Part of the population took a very dim view of the blues because of its associations with liquor, marijuana and a dissolute way of life; with the appearance of gospel songs, and in order not to miss the slightest chance of being booked to play — or even a nickel in a hat — many bluesmen often had a religious songbook to fall back on (spirituals, gospel) alongside a secular repertoire (blues, popular songs), but their spontaneous music style varied little from one tendency to the other (the “guitar evan-gelists”.)

In Europe’s written tradition, there was some sophisticated and subtle dillydallying over the ideal way to suitably perform compositions by musicians who were often long dead. Music’s most popular artists, among them the exceptional Maria Callas or the Afro-American Paul Robeson, were among those who dared lend their own strong personalities to the music. The Afro-American tradition of spirituals and gospels went much further in this sense, in encouraging spontaneity, feeling and originality to the point where great liberties were taken with melody, arrangements, tempo and lyrics. This kind of religious music suggested liberty through its own freedom of musical expression, and through personalities that came to bloom which, after all, was the gift of God. Like the blues, spirituals and gospel were transformed in the course of the Fifties. They gave birth to a secular style that encouraged people to dance, a style where feelings of love replaced Christian themes. The intensity of performance and stylistic array found in spirituals was used in jazz and blues at the beginning of the century. In turn, gospel impregnated the sensibilities of such wonderful artists as Billie Holiday or Dinah Washington, and then passed into rock and rhythm ‘n’ blues, two terms that designated the same music (cf. the Frémeaux set Race Records 1942-1955 - Black Rock Music Forbidden on U.S. Radio, FA 5600).

The mutational process in which gospel and blues were transformed into soul is clarified in detail in the complementary set Roots of Soul 1928-1962 elsewhere in this collection. With important singers like Louis Armstrong or Jack Teagarden, New Orleans provided a whole school of performers who became classified as “soul” artists. The dramatic atmosphere, transmitting emotions, generated by these extremely heartfelt performances is the legacy, the substance and the soul of “soul music”. You can find this particular tension as much in the voice of Louis Armstrong, the tutelary figure of the whole of Black America, as in the first, pure, soul classics like Johnny Adams’ A Losing Battle or Irma Thomas’ Hitting on Nothing in 1962. Gospel opened the doors to emotion in American popular music. It encouraged all impulses, every inspiration, as Mahalia Jackson, the Queen of the genre, shows here, with singing that is intuitive and spontaneous.

ROCK AND ROLL

Soul music comes down from spirituals, gospel, blues, jazz — but also, perhaps, even more directly from rock, a style that was itself a catalyst for these four founding genres. The greatest names in soul excelled in rock, from James Brown to Otis Redding, and from Art Neville to Little Richard, who would record almost all his rock classics in the studio of Cosimo Matassa in New Orleans, with the group of Dave Bartholomew.14 After Little Richard’s religious reclusion at the end of 1957, Larry Williams was his successor at Specialty. A pianist also, he would record with the same musicians, in the same studio, and in the same style: pure rock, but also soul ballads. Like the rock tune Bonie Moronie, his slow number Just Because was “covered” in 1975 by John Lennon in his famous album entitled Rock ‘n’ Roll. The excellent Larry Williams made a great impression on The Beatles: they recorded his compositions Bad Boy, Dizzy Miss Lizzie and Slow Down, all of them sung by Lennon. As for The Rolling Stones, in recording She Said Yeah they, too, catapulted a Larry Williams creation into the Sixties’ general culture, as they did for Rain in my Heart by Irma Thomas, (also the originator of “Time Is on my Side”), Benny Spellman’s Fortune Teller and I’m a King Bee.

Roy Brown was initially a gospel singer; like Little Richard and later James Brown, he became a blues and rock convert. He influenced Elvis Presley, who turned his composition “Good Rockin’ Tonight” into one of his first Sun hits (1954). Here Roy Brown sings the obscure Hard Luck Blues (1950), whose melody was plagiarized by Mae Boren Axton and Tommy Durden, the writers of “Heartbreak Hotel”, probably Elvis Presley’s most famous song. Many elements of “Heartbreak Hotel” (1956) recall soul stereotypes: its theme, its pathos, the slow tempo, the arrangement, its embellishments and the variations in vocal intensity… Elvis, who’d seen Roy Brown onstage, wasn’t the only one to draw inspiration from this piece epitomizing his style, as Little Midnight’s Four O’Clock Blues resembles it even more — but five years before “Heartbreak Hotel”.

SOUL

Soul could take its definition from the intensity of its vocal performances, the emotion that they transmit by means of its various codes, and the legacy of Afro-American cultures. These emotions are most often poignant, as here in numerous blues pieces (Lonnie Johnson, Little Sonny Jones, Guitar Slim, etc.) or in the work of the fantastic Snooks Eaglin, a versatile blind singer/guitarist who was influenced by Ray Charles. The emotion can be full of fervour, as in the spirituals of Utah Smith; cheerful and gay, as in Louis Armstrong; and even full of humour, as shown in pieces from Clarence “Frogman” Henry or Huey “Piano” Smith. To be truthful, these superficial labels — “blues”, “jazz”, “soul”, “rhythm and blues” or “rock” — cannot be affixed to this or that artist due to the fact that most of them sang these interconnected styles in turn. They mixed them together in the clubs of Louisiana and in the city’s sole studio — most often accompanied by the same musicians, the sidemen in the nebula surrounding Dave Bartholomew.

Born in 1918, Dave Bartholomew had studied trumpet with Peter Davis, who was Louis Armstrong’s teacher. He turned professional and played with various jazz bands after the war (spent playing in a military band), and in 1947 he formed a band that musicologist Robert Palmer described as “the model for all the first rock groups in the whole world.” They played for two years, broadcasting radio shows out of the store owned by Cosimo Matassa and building an excellent local reputation. Bartholomew consolidated his band with a few of the city’s best instrumentalists, borrowing many from his rival Paul Gayten, whose band was already renowned. Among them was drummer Earl Palmer, an essential player and one of the major drummers in rock history: Earl pioneered the use of, and emphasis on, the backbeat (the accent on beats 2 and 4 already heard on Harry James’ “Backbeat Boogie” in 1939 as well as other jazz/blues titles. Palmer had studied music and knew how to sight-read and compose. Dave Bartholomew became the Artistic Director at Imperial Records, and first recorded for them in Cosimo Matassa’s J&M studio in 1947. Bassist Frank Fields, guitarist Earl McLean and sax-players Clarence Hall, Joe Harris and Red Tyler were already inside Matassa’s rudimentary studios in 1949, as were pianists Salvador Doucette and Fats Domino; the latter was an instant phenomenon, selling tens of millions of records at the beginning of the Fifties. Then reed players Lee Allen, Herb Hardesty, Plas Johnson and others joined the inner sanctum, consolidating the stable’s “A” team before even more aces arrived, like Harold Battiste and Roy Montrell (see discography). Tiny, basically equipped, and located in the back shop of the store belonging to Matassa’s parents on Rampart Street, “J&M” was the first studio deserving of the name in New Orleans. A sizeable part of the present set was recorded in this legendary place where the great classics of Fats Domino, Ray Charles, Little Richard15 and hundreds of others were taped with Bartholomew’s crew. A professional and an excellent organizer, at the end of the Forties the trumpeter had become the most important producer, arranger and composer in a city where music was everywhere. After leaving Imperial in 1950 he worked with other labels, among them Specialty (for Little Richard and then Larry Williams), Decca and King. He was a brilliant singer (and soul precursor), as you can hear on High Flying Woman and Another Mule, and also capable of producing the best rock arrangements and accompaniment (cf. the Art Neville and Larry Williams tracks here.) If Dave Bartholomew excelled in the blues, he also composed songs where the melodies were more ambitious, heralding the style that people would call “soul music” at the beginning of the Sixties. He wrote and produced Fats domino’s greatest hits in this style, among them the Blue Monday classic, and Smiley Lewis singing I Hear You Knocking. He also produced I’m Gone, Shirley and Lee’s first hit. To cap it all, as a major rock stylist Bartholomew made an essential contribution to the birth of soul. His collaboration with Fats Domino made the pair the second-most successful record-sellers of the period — 65 million records in total — after Elvis.

Afterwards, his musicians continued to work with different arrangers, and they reappear throughout this collection. Cosimo Matassa opened a new studio and gradually a “100% soul” sound took hold. Pianists like Doucette, Allen Toussaint and Art Neville renewed the city’s pianist-arranger tradition, creating original styles that have since been copied everywhere. They count as historic pioneers of both soul and funk, which would develop from Memphis to Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York and Detroit. After a few sessions on guitar, Mac Rebennack (Dr. John) was completely adopted by the studio’s top crew in around 1960, and his case was quite atypical — a white musician in the middle of this black culture — like that of Roland Stone, “the soul-est of the white singers”, or Johnny Winter in nearby Texas. Great “soul” music artists (using harmonic sequences that were increasingly distinct from blues and the bases of gospel) abounded by the end of the Fifties, but the term “soul” didn’t catch on until around 1963.

The cream of these artists associated with the sound of New Orleans has been gathered here: Reggie Hall, Eddie Bo, Snooks Eaglin, Johnny Adams, Willie Tee, John “Scarface” Williams — the singer with Huey Smith’s Clowns (under the name The Tick Tocks), and Chief of The Apache Hunters, one of the Mardi Gras Indians tribes — and lastly Irma Thomas, the soul queen of New Orleans, all pioneered this music genre. The richness of the city’s golden age of rhythm and blues makes it impossible to include all the titles that deserve to appear in this anthology, like “Mother in Law” by Ernest K-Doe, or so many others recorded by the artists represented here; but the detail in the music of this collection, from spiritual roots to the blues, and from jazz to gospel and pure soul, is more than enough to make the birth of the region’s influential soul style, and the trail it blazed, sufficiently clear.

Bruno Blum, December 2015.

Adapted into English by Martin DAVIES

Thanks to Dale Blade, Augustin Bondoux, Jon Cleary, Jean-Michel Colin, Stéphane Colin, Gilles Conte, Daniel Gondol/Le Jockomo, Gary Karp, Gilles Pétard, Gilbert Shelton, Nicolas Teurnier/Soul Bag and Michel Tourte.

© 2016 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

1. Cf. Virgin Islands Queltesbe & Calypso 1956-1960 (FA 5403) in this collection.

2. Cf. Haiti - Meringue & Konpa 1952-1962 (FA 5615).

3. Cf. Dominican Republic Merengue 1949-1962 (FA 5450).

4. Cf. Jamaica - Mento 1951-1958 (FA 5275).

5. Cf. Zydeco - Black Creole, French Music and Blues 1929-1972 (FA 5616).

6. Cf. Jamaica - Jazz 1931-1962 (future release) and Swing Caraïbe - Premiers jazzmen antillais à Paris 1929-1946 (FA 069) in this collection.

7. Cf. Haiti Vodou - Folk Trance Possession 1937-1962 (FA 5626) and Jamaica Folk Trance Possession - Roots of Rastafari 1939-1961 (FA 5384).

8. Cf. Roots of Funk 1947-1962 (FA 5498).

9. Cf. the two 3CD sets The Indispensable Bo Diddley (FA 5376 & FA 5406).

10. Cf. Slavery in America - Redemption Songs 1914-1972 (FA 5467) and Gospel Volume 1 - Negro Spirituals and Gospel Songs 1926-1942 (FA 008).

11. Cf. Jamaica Jazz 1931-1962 (future release) and Swing Caraïbe 1929-1946 (FA 069).

12. Cf. Cajun - Louisiane 1928 - 1939 (FA 019).

13. The James Wee Willie Wayne version that popularized this title in 1951 is included in the set Roots of Punk Rock Music 1926-1962 (FA 5415).

14. Cf. The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607).

15. Cf. The Indispensable Little Richard 1951-1962 (FA 5607).

Roots of Soul - New Orleans 1941-1962

Disc 1 - The Roots 1941-1957

1. JUNKER’S BLUES - Champion Jack Dupree

(Willie Hall as “Drive’ em Down”, credited to William Thomas Dupree aka Champion Jack Dupree)

William Thomas Dupree as Champion Jack Dupree-v, p; Wilson Swain or Ransom Knowling-b. Chicago, January 28, 1941.

2. TWO WINGS/EVERY MAN’S GOT TO LAY DOWN AND DIE - Reverend Utah Smith

(traditional/Ola Mae Terrel)

Utah Smith-v, g; Congregation-v, handclaps; radio speaker-v. New Orleans, 1947.

3. HEY LITTLE GIRL - Roland (“Baldhead”) Byrd and his New Orleans Rhythm

(Henry Roeland Byrd aka Professor Longhair)

Henry Roeland Byrd aka Roy Byrd aka Professor Longhair aka Fess -v, p; John Boudreaux-d. Atlantic 947. New Orleans, circa December, 1949.

4. BLUES STAY AWAY FROM ME - Lonnie Johnson

(Alton Delmore, Rabon Delmore, Wayne Raney, Henry Glover)

Alfonzo Johnson as Lonnie Johnson-v, g; Simeon Hatch-p; Frank Skeete-b; Leon Abramson-d. King 4336, K 5806-2. Cincinnati, November 29, 1949.

5. HER MIND IS GONE - Roy Byrd and his Blues Jumpers

(Henry Roeland Byrd aka Professor Longhair)

Roy Byrd aka Professor Longhair-v, p; Lee Allen or Leroy Rankin aka Batman-ts; George Miller-b; Lester Alexis aka Duke-d. Mercury 8184, 7804-3. New Orleans, February, 1950.

6. HARD LUCK BLUES - Roy Brown and his Mighty-Mighty Men

(Roy James Brown aka Roy Brown)

Roy James Brown as Roy Brown-v; Wilbur Harden-tp; Jimmy Griffin-tb; Johnny Fontennette-ts; Harry Porter-bs; Buddy Griffin-p; Willie Gaddy-g; Ike Isaacs-b; Calvin Shields-d. Deluxe 3304, D-1513. Cincinnati, April 19, 1950.

7. FOUR O’CLOCK BLUES - Little Mr. Midnight

(Eddie Durham)

Little Mr. Midnight-v; Paul Leon Gayten as Paul Gayten-p; tp, ts, bs, d. J&M Studio, 838 North Rampart St., New Orleans, September, 1950.

8. ME AND MY CRAZY SELF - Lonnie Johnson

(Henry Glover, Sydney Nathan aka Lois Mann)

Alfonzo Johnson as Lonnie Johnson-v, g; Wilburt Prysock aka Red-ts; James Robinson-p; Clarence Mack-b; Calvin Shields-d. King 4510, K 9094-2. Cincinnati, October 26, 1951.

9. HIGH FLYING WOMAN - Dave Bartholomew

(David Louis Bartholomew aka Dave Bartholomew)

David Louis Bartholomew as Dave Bartholomew-v, tp; Willie Wells-tp; Holly Dismukes-as; Charles Edwards aka Lefty-ts; John Faire-g; Todd Rhodes-p, direction; Teddy Buckner-bs; Joe Williams-b; William Benjamin aka Benny-d. King 4585, K-9081. Cincinnati, August 16, 1951.

10. LAWDY MISS CLAWDY - Lloyd Price and his Orchestra

(Lloyd Price)

Lloyd Price-v; David Louis Bartholomew as Dave Bartholomew-tp; Joe Harris-as; Herb Hardesty-ts; Ernest McLean-g; Antoine Dominique Domino aka Fats Domino-p; Joe Harris-p; Frank Fields-b; Earl Palmer-d. Specialty 428. J&M Studio, March 13, 1952.

11. I’M GONE - Shirley and Lee with Dave Bartholomew and Orchestra

(Leonard Lee, David Louis Bartholomew aka Dave Bartholomew)

Shirley Goodman-v; Leonard Lee-v; David Louis Bartholomew as Dave Bartholomew-tp; Joe Harris-as; Clarence Ford-bs; Herb Hardesty-ts; Ernest McLean-g; Salvador Doucette-p; Frank Fields-b; Earl Palmer-d. Aladdin 3153, NO 2015-2. J&M Studio, New Orleans, June 24, 1952.

12. JIMMIE LEE - Lloyd Price

(Lloyd Price)

Lloyd Price-v; Bill Lundy-as; Lawrence Marioneaux, Neely Simmons-ts; possibly Duncan Conelly, Jr.-g; possibly William Brown-p; Curtis Mitchell-b; Charles Otis-d. Specialty 494. Los Angeles, October 13, 1952.

13. TWO WINGS - Reverend Utah Smith

(traditional)

Utah Smith-v, g; Congregation-v, handclaps. Checker 785, U-7539. New Orleans, 1953.

14. LUCY MAE BLUES - Frankie Lee Sims

(Frankie Lee Sims)

Frankie Lee Sims-v, g; b; Herbert Washington-d. Specialty 459. Dallas, March 5, 1953.

15. TEND TO YOUR BUSINESS BLUES - Little Sonny Jones

(Johnny Jones aka Little Sonny Jones)