- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

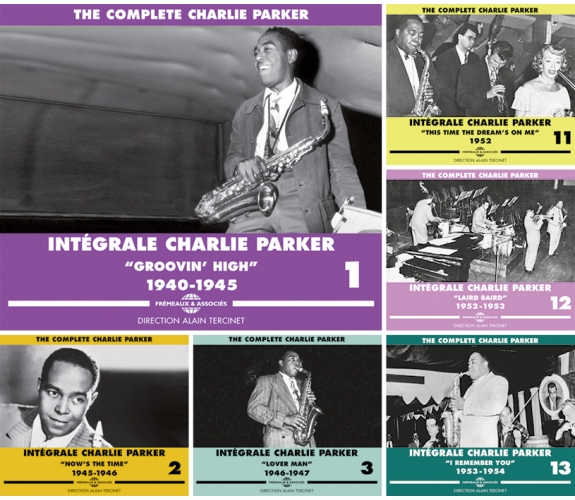

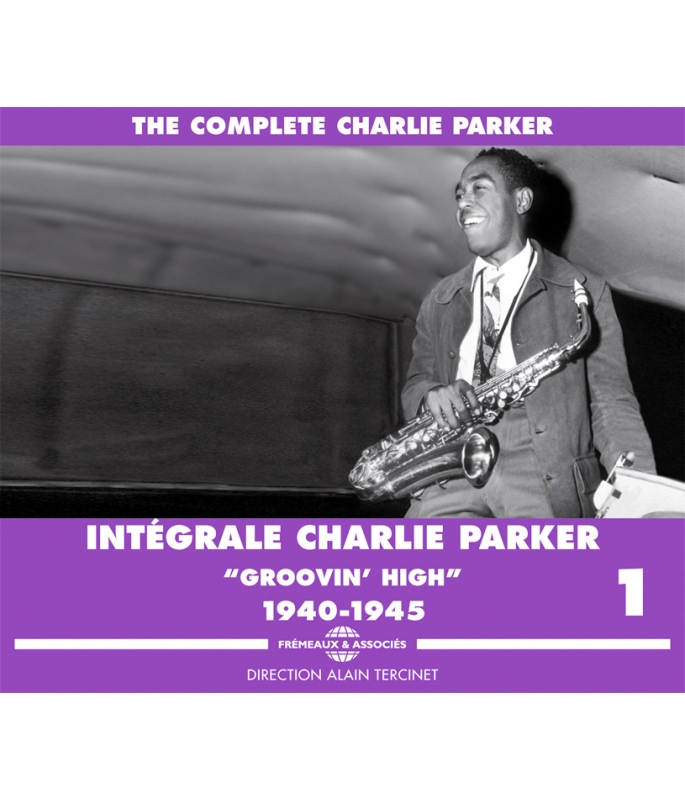

Complete Charlie Parker 1940-1953

Réf. : FA1331 / FA1332 / FA1333 / FA1334 / FA1335 / FA1336 / FA1337 / FA1338 / FA1339 / FA1340 / FA1341 / FA1342 / FA1343

Artistic Direction : ALAIN TERCINET

Label : Frémeaux & Associés

Total duration of the pack : 47 hours 8 minutes

Nbre. CD : 40

Toute l’œuvre de l'incomparable jazzman en 39 CD

Bird était un peu comme un soleil qui nous donnait de l’énergie…Dans n’importe quelle situation musicale, ses idées fleurissaient et inspiraient tous ceux qui étaient présents.

Max ROACH

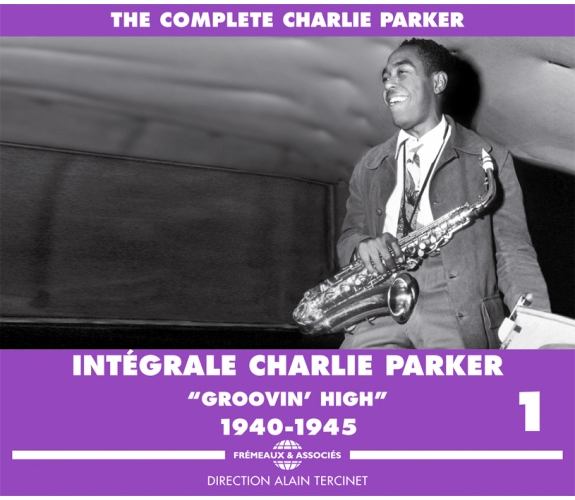

GROOVIN' HIGH - 1940-1945

“Hootie, would you like it if I came to the bandstand looking like a doctor, and played like a doctor?” Charlie Parker to Jay McShann

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

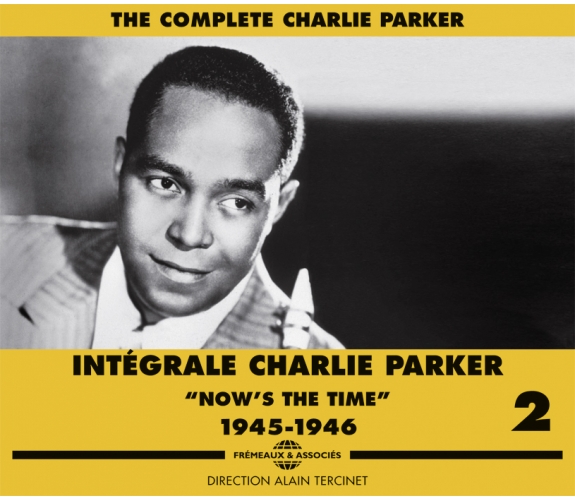

NOW'S THE TIME - 1945-1946

A lot of people didn't understand his music and when they started to do so, they still wondered how he did it. Charlie Parker remained a mystery.

Clint Eastwood

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

CD 1 : Red Norvo and his Selected Sextet (NYC, 6/6/1945) Hallelujah! • Hallelujah! • Hallelujah! • Get Happy • Get Happy • Slam Slam Blues • Slam Slam Blues • Congo Blues • Congo Blues • Congo Blues • Congo Blues • Congo Blues • Sir Charles and his All Stars (NYC, 4/9/1945) Takin’ Off • If I Had You • 20th Century Blues • The Street Beat • Charlie Parker’s Ree Boppers (NYC, 26/11/1945) Billie’s Bounce • Billie’s Bounce • Billie’s Bounce • Warming Up a Riff.

CD 2 : Charlie Parker’s Ree Boppers (NYC, 26/11/1945) Billie’s Bounce • Billie’s Bounce • Now’s the Time • Now’s The Time • Now’s The Time • Now’s The Time • Thriving On a Riff • Thriving On A Riff • Thriving On A Riff • Meandering • Koko • Koko • Dizzy Gillespie and his Rebop Six (Radio/Broadcast, Billy Berg’s Supper Club, LA, 17/12/1945) How High the Moon • 52nd Street Theme • Slim Gaillard and His Orchestra (Hollywood, 29/12/1945) Dizzy Boogie • Dizzy Boogie • Flat Foot Floogie • Flat Foot Floogie • Popity Pop • Slim’s Jam • Dizzy Gillespie and his Rebop Six (Radio/Broadcast, Afrs Jubilee, Hollywood, 29/12/1945) • Dizzy Atmosphere • Groovin’ High • Shaw ‘nuff. (Radio/Broadcast, Rudy Vallée Show, LA 24 /1/1946) Salt Peanuts Radio Transcription

CD 3 : Jazz At The Philharmonic (Philharmonic Auditorium, LA, 28/1/1946) • Sweet Georgia Brown • Blues For Norman • I Can’t Get Started • Oh! Lady be Good • After You’ve Gone • Dizzy Gillespie Quintet (Private Recording, Freddy James Home, Hollywood, 3/2/1946) Lover, come back to me • Tempo Jazzmen (Glendale, 5/2/1946) Diggin’ Diz • Charlie Parker Quintet (Radio/Broadcast, Finale Club, LA, march 1946) Billie’s Bounce • All The Things You Are • Blue ‘N’ Boogie • Anthropology • Ornithology

Rights: Frémeaux & Associés.

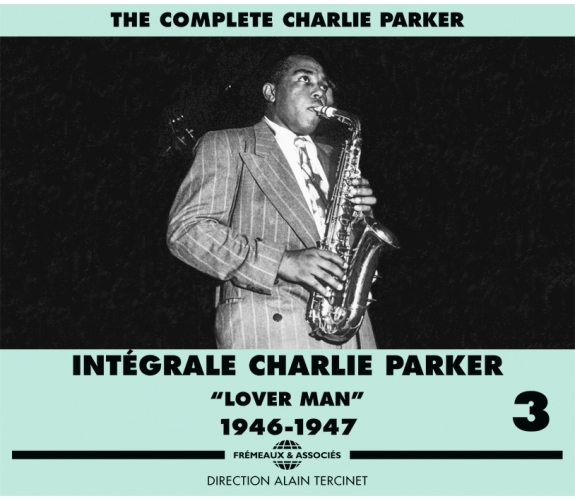

LOVER MAN - 1946-1947

“When Bird left New York he was a king, but out in Los Angeles he was just another broke, weird, drunken nigger playing some strange music. Los

Angeles is a city built on celebrating stars and Bird didn’t look like no star.” M. DAVIS

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

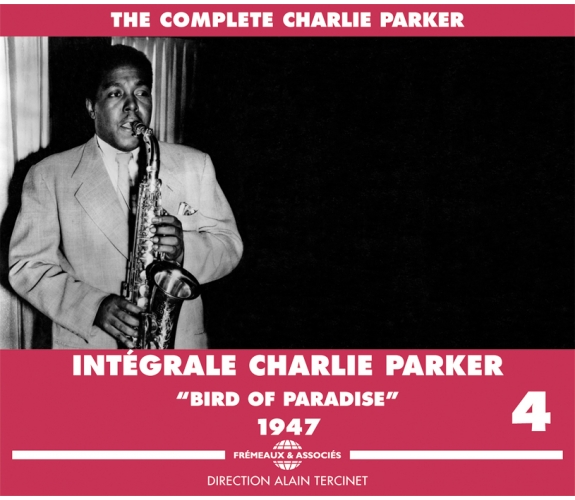

BIRD OF PARADISE - 1947

“When Charlie Parker became popular with his be-bop tunes, everybody had to change his style – the drummer, the piano player, the singer, whoever” Anita O’Day (High Times, Hard Times)

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

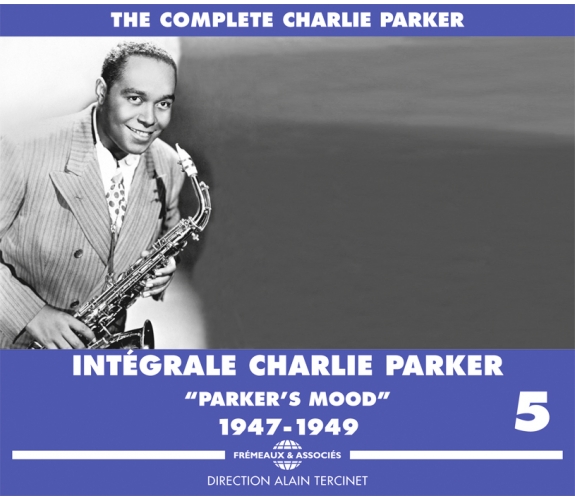

PARKER’S MOOD 1947-1949

“Bird was like the sun, giving off the energy we drew from him… In any musical situation, his ideas just bounded out, and his inspired anyone who was around.” Max ROACH

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

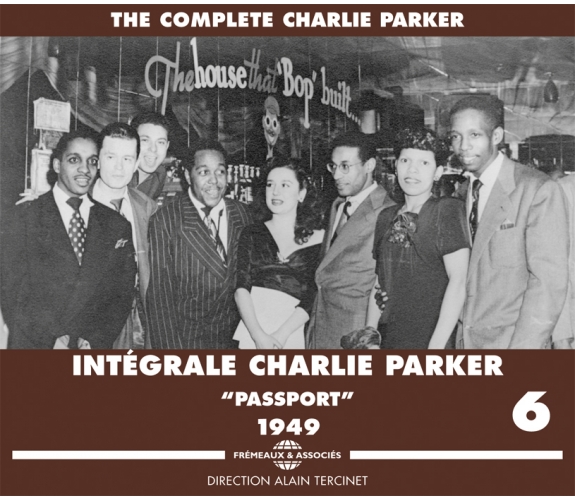

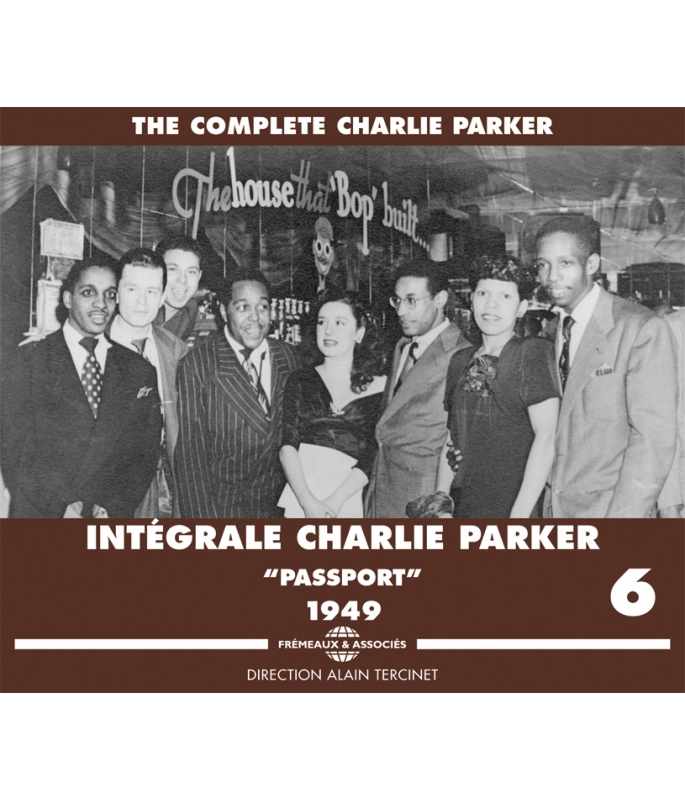

“PASSPORT” 1949

“You really have to be blind to all the evidence if you refuse to see that Parker’s calibre was at least as prodigious as that of the greatest musicians of earlier generations.” Boris VIAN

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

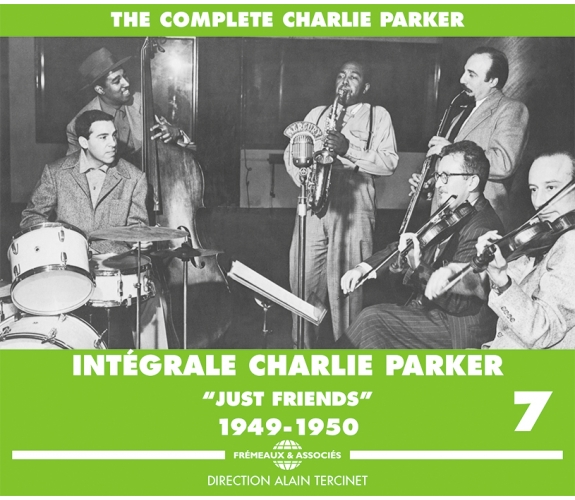

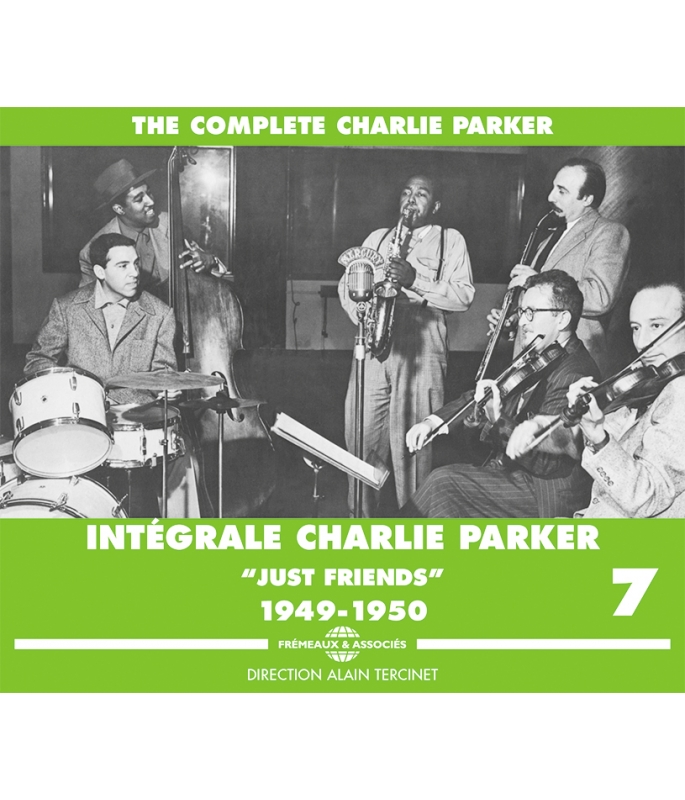

JUST FRIENDS - 1949-1950

« Charlie Parker did all the things I would like to do and more – he really had a genius, see. He could do things and he could do them melodiously so that anybody, the man in the street, could hear – that’s what I haven’t reached, that’s what I’d like to reach. » John COLTRANE

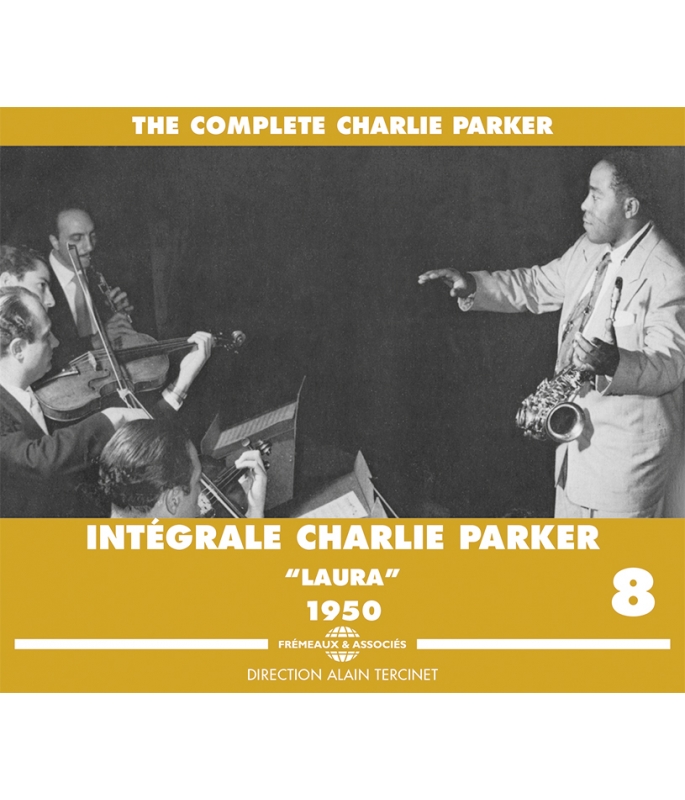

LAURA - 1950

“Melody... If you were being tortured and could only keep one — even if the torture was fierce — then it would have to be Laura. Played by Charlie Parker, Laura steps through the gates of Paradise wreathed in little scrolls of pure, undiluted happiness. Nothing can spoil that moment every time I hear it.” Jean-Pierre MARIELLE (Le grand n’importe quoi, Calmann-Lévy, 2010)

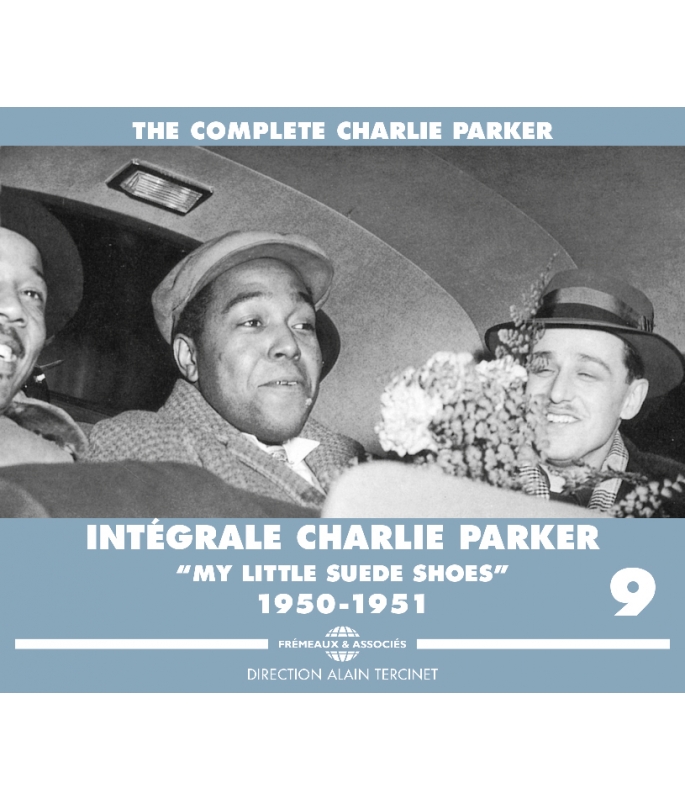

MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES - 1950-1951

“It’s true that I think of Charlie Parker as being impassable.” René URTREGER

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

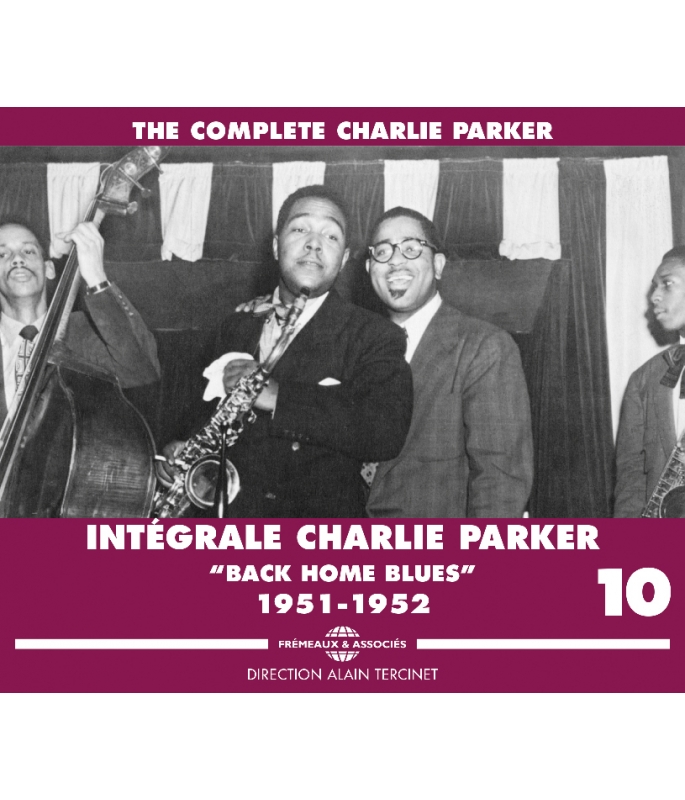

BACK HOME BLUES 1951-1952

“My vote is definitely for Charlie Parker. I’ve worked with all the great names you mentioned, but Charlie Parker was the originator and innovator of the century.” Buddy de FRANCO

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts.

Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

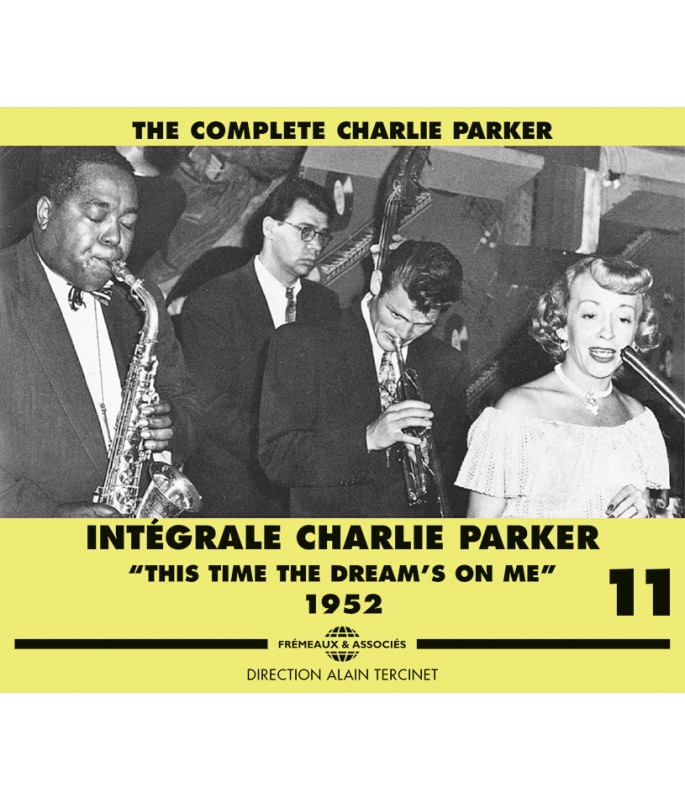

THIS TIME THE DREAM’S ON ME - 1952

“There was something kind of inevitable about the way Bird played, and it was very direct and very melodic and it transcended the limitations of the horn.” Gerry MULLIGAN

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

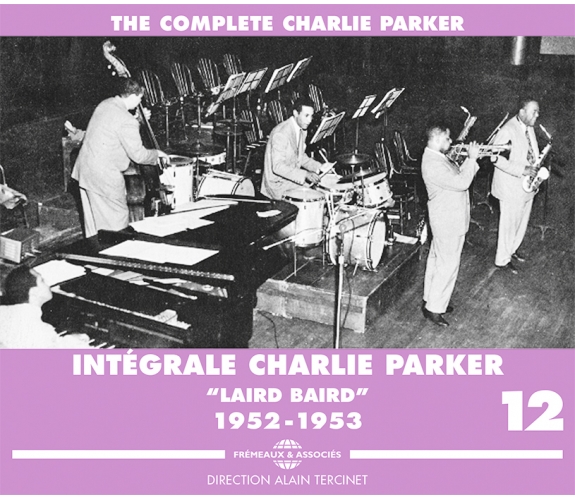

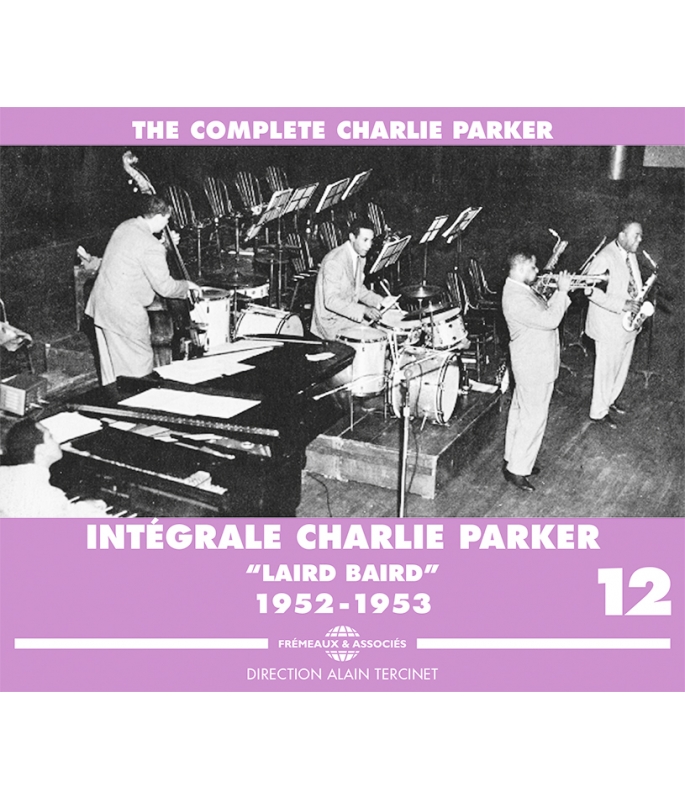

“LAIRD BAIRD” 1952-1953

“Charlie Parker lifted jazz music off the dance floor and into the stratosphere !” Joe LOVANO

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

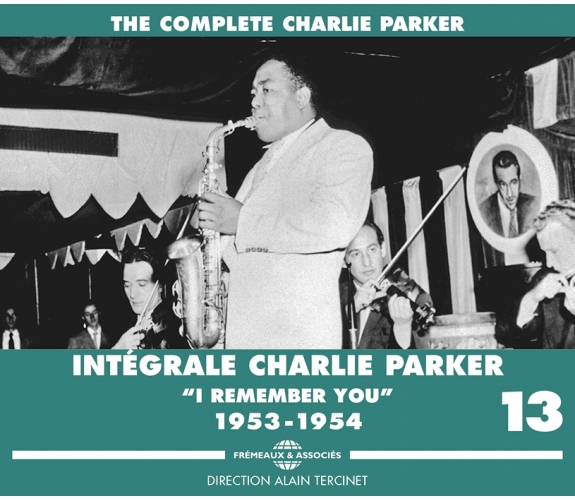

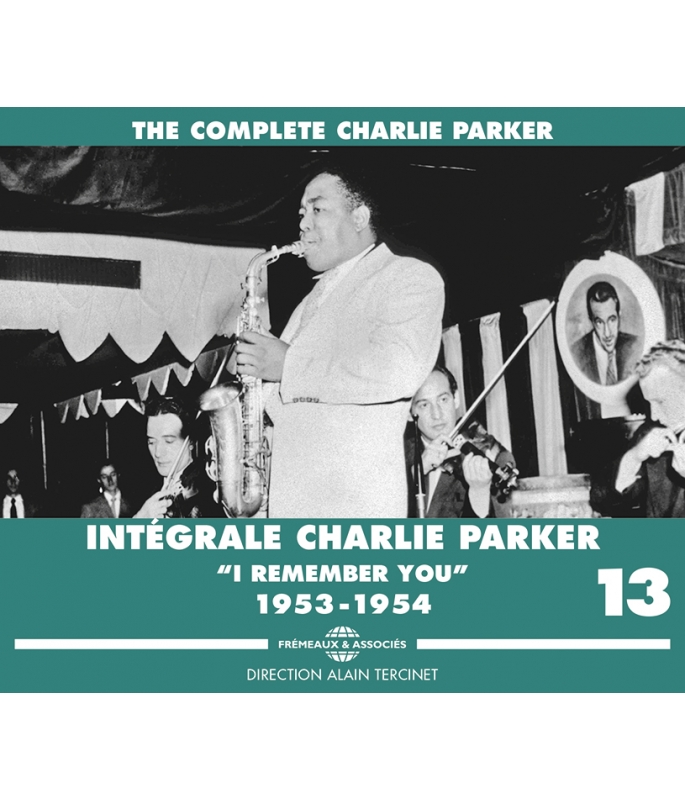

CHARLIE PARKER

“Bird would throw his genius out of every window. And then one day, his instrument. And then on another day, the instrument of that instrument, this man full of candour and enigma who talked to the birds.” Alain GERBER

The aim of 'The Complete Charlie Parker', compiled for Frémeaux & Associés by Alain Tercinet, is to present (as far as possible) every studio-recording by Parker, together with titles featured in radio-broadcasts. Private recordings have been deliberately omitted from this selection to preserve a consistency of sound and aesthetic quality equal to the genius of this artist.

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Honey And BodyCharlie Parker00:03:391940

-

2I'Ve Found A New BabyJay McShann Octet00:03:011940

-

3Body And SoulJay McShann Octet00:02:531940

-

4Moten SwingJay McShann Octet00:02:501940

-

5CoquetteJay McShann Octet00:03:111940

-

6Oh Lady Be GoodJay McShann Octet00:03:001940

-

7Wichita BluesJay McShann Octet00:03:121940

-

8Honeysuckle RoseJay McShann Octet00:03:011940

-

9SwingmatismJay McShann and His Orchestra00:02:461941

-

10Hootie BluesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:03:041941

-

11Dexter BluesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:03:051941

-

12St Louis MoodJay McShann and His Orchestra00:04:161942

-

13I'M Forever Blowing BubblesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:04:081942

-

14Hootie BluesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:04:381942

-

15SwingmatismJay McShann and His Orchestra00:04:131942

-

16CherokeeClark Monroe's Band00:02:541942

-

17Lonely Boy BluesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:03:001942

-

18The Jumpin' BluesJay McShann and His Orchestra00:03:071942

-

19Sepian BounceJay McShann and His Orchestra00:03:121942

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1CherokeeCharlie Parker Trio00:03:121942

-

2My Heart Tells MeCharlie Parker Trio00:03:201942

-

3I Found A New BabyCharlie Parker Trio00:03:331942

-

4Body And SoulCharlie Parker Trio00:03:451942

-

5Sweet Georgia BrownBob Redcross Jam Sessions00:07:451943

-

6Yardin With YardBob Redcross Jam Sessions00:04:211943

-

7Tiny's TempoTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:021944

-

8Tiny's TempoTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:011944

-

9Tiny's TempoTiny Grimes Quintet00:02:551944

-

10I'll Always Love You Just The SameTiny Grimes Quintet00:02:581944

-

11I'll Always Love You Just The SameTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:001944

-

12Romance Without FinanceTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:071944

-

13Romance Without FinanceTiny Grimes Quintet00:01:021944

-

14Romance Without FinanceTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:071944

-

15Romance Without FinanceTiny Grimes Quintet00:00:451944

-

16Romance Without FinanceTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:041944

-

17RedcrossTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:171944

-

18RedcrossTiny Grimes Quintet00:03:101944

-

19What's The Matter NowClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:521945

-

20I Want Every Bit Of ItClyde Hart's All Stars00:03:141945

-

21That's The BluesClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:591945

-

224-F BluesClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:241945

-

23G-I BluesClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:291945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Dream Of YouClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:571945

-

2Seventh AvenueClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:541945

-

3Sorta KindaClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:451945

-

4Oh, Oh, My, My, Oh, OhClyde Hart's All Stars00:02:521945

-

5Lay It DownClyde Bernhardt and Jay McShann's Kansas City Rhythm00:02:261945

-

6Trifflin' WomanClyde Bernhardt and Jay McShann's Kansas City Rhythm00:03:221945

-

7So Good This Mornin'Clyde Bernhardt and Jay McShann's Kansas City Rhythm00:02:131945

-

8Would You Do Me A FavorClyde Bernhardt and Jay McShann's Kansas City Rhythm00:03:071945

-

9Floogie BooCootie Williams Sextet00:03:461945

-

10Groovin' HighDizzy Gillepsie Sextet00:02:451945

-

11All The Things You AreDizzy Gillepsie Sextet00:02:511945

-

12Dizzy AtmosphereDizzy Gillepsie Sextet00:02:511945

-

13Salt PeanutsDizzy Gillepsie and His All Stars00:03:201945

-

14Shaw NuffDizzy Gillepsie and His All Stars00:03:051945

-

15Lover ManDizzy Gillepsie and His All Stars00:03:251945

-

16Hot HouseDizzy Gillepsie and His All Stars00:03:151945

-

17What More Can A Woman DoSarah Vaughan and His Octet00:03:041945

-

18I'D Rather Have A MemorySarah Vaughan and His Octet00:02:441945

-

19Mean To MeSarah Vaughan and His Octet00:02:441945

-

20Sweet Georgia BrownDizzy Gillepsie Sextet00:03:291945

-

21Blue 'N BoogieDizzy Gillepsie Quintet00:03:091945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1HallelujahRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C HeardClifford Grey, Léo Robin00:04:011945

-

2HallelujahRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C HeardClifford Grey, Léo Robin00:04:071945

-

3HallelujahRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C HeardClifford Grey, Léo Robin00:04:121945

-

4Get HappyRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C HeardTed Koehler00:04:061945

-

5Get HappyRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C HeardTed Koehler00:03:501945

-

6Slam Slam BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:05:061945

-

7Slam Slam BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:04:311945

-

8Congo BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:01:071945

-

9Congo BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:01:161945

-

10Congo BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:04:011945

-

11Congo BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:03:541945

-

12Congo BluesRed Norvo, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Flip Phillips, Teddy Wilson, Slam Stewart, J.C Heard00:03:571945

-

13Takin OffSir Charles Thompson, Charlie Parker, Buck Clayton, Dexter Gordon, Danny Barker, Jimmy Butts, J.C Heard00:03:111945

-

14If I Had YouSir Charles Thompson, Charlie Parker, Buck Clayton, Dexter Gordon, Danny Barker, Jimmy Butts, J.C Heard00:03:021945

-

1520Th Century BluesSir Charles Thompson, Charlie Parker, Buck Clayton, Dexter Gordon, Danny Barker, Jimmy Butts, J.C Heard00:02:551945

-

16The Street BeatSir Charles Thompson, Charlie Parker, Buck Clayton, Dexter Gordon, Danny Barker, Jimmy Butts, J.C Heard00:02:361945

-

17Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:02:431945

-

18Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:01:451945

-

19Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:081945

-

20Warming Up a RiffCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:02:341945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:01:411945

-

2Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:101945

-

3Now's the TimeCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:00:211945

-

4Now's the TimeCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:00:381945

-

5Now's the TimeCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:091945

-

6Now's the TimeCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:171945

-

7Thriving On a RiffCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:001945

-

8Thriving On a RiffCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:00:251945

-

9Thriving On a RiffCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:02:551945

-

10MeanderingCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:03:151945

-

11KokoCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Hakim Sadik, Russel Curley, Max Roach00:00:391945

-

12KokoDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie Williams00:02:561945

-

13How High the MoonDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie WilliamsNancy Hamilton00:03:551945

-

1452Nd Street ThemeSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty Singleton00:01:531945

-

15Dizzy BoogieSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty Singleton00:03:101945

-

16Dizzy BoogieSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty Singleton00:03:171945

-

17Flat Floot FloogieSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty SingletonB. Green, S. Stewart00:02:351945

-

18Flat Floot FloogieSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty SingletonB. Green, S. Stewart00:02:501945

-

19Popity PopSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty Singleton00:03:001945

-

20Slim's JamSlim Gaillard, Charlie Parker, John Birks, Jack McVea, Dodo Marmarosa, Bam Brown, Zutty Singleton00:03:201945

-

21Dizzy Atmosphere-1Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie Williams00:04:351945

-

22Groovin HighDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie Williams00:06:031945

-

23Shaw NuffDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie Williams00:04:461945

-

24Salt PeanutsDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, Ray Brown, Stan Levey, Ernie Williams00:02:051945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Sweet Georgia BrownCharlie Parker, John Birks, Al Killian, Willie Smith, Lester Young, Charlie Ventura, Mel Powell, Billy Hadnott, Lee YoungMacéo Pinkard00:09:371945

-

2Blues for NormanCharlie Parker, John Birks, Al Killian, Willie Smith, Lester Young, Charlie Ventura, Mel Powell, Billy Hadnott, Lee Young00:08:381945

-

3I Can't Get StartedCharlie Parker, John Birks, Al Killian, Willie Smith, Lester Young, Charlie Ventura, Mel Powell, Billy Hadnott, Lee YoungIra Gershwin00:09:151945

-

4Oh Lady Be GoodCharlie Parker, John Birks, Al Killian, Willie Smith, Lester Young, Charlie Ventura, Mel Powell, Billy Hadnott, Lee YoungIra Gershwin00:11:121945

-

5After You've GoneCharlie Parker, John Birks, Al Killian, Willie Smith, Lester Young, Charlie Ventura, Mel Powell, Billy Hadnott, Lee YoungLayton Turner00:07:401945

-

6Lover Come Back to MeDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Red CallenderO.Hammerstein00:03:341945

-

7Diggin DizDizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Lucky Thompson, George Handy, Arvin Garrison, Ray Brown, Stan Levey00:02:561945

-

8Billie's BounceCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Albany, Addison Farmer , Chuck Thompson00:03:511945

-

9All the Things You AreCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Albany, Addison Farmer , Chuck ThompsonO.Hammerstein00:05:171945

-

10Blue'n BoogieCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Albany, Addison Farmer , Chuck ThompsonF. Paparelli00:05:181945

-

11AnthropologyCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Albany, Addison Farmer , Chuck ThompsonDizzy Gillespie00:02:511945

-

12OrnithologyCharlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Albany, Addison Farmer , Chuck ThompsonB. Harris00:05:061945

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker Septet00:02:591946

-

2Moose The Mooche (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:041946

-

3Moose The Mooche 2Charlie Parker Septet00:02:561946

-

4Yarbird SuiteCharlie Parker Septet00:02:401946

-

5Yardbird Suite (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:02:551946

-

6OrnithologyCharlie Parker Septet00:03:011946

-

7Ornithology (Bird Lore)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:191946

-

8Ornithology (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:021946

-

9Night In Tunisia (Famous also break)Charlie Parker Septet00:00:491946

-

10Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker Septet00:03:081946

-

11Night In Tunisia (Master)Charlie Parker Septet00:03:051946

-

12AnnoucementCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:02:161946

-

13Japt BluesCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:11:021946

-

14I Got RhythmCharlie Parker - Jazz At The Philharmonic00:13:001946

-

15Announcement MedleyCharlie Parker - Jatp All Stars00:01:201946

-

16Medley Tea For Two Body And Soul CherokeeCharlie Parker - Jatp All Stars00:08:281946

-

17Ornithology 2Charlie Parker/Nat King Cole Trio and Guest00:03:101946

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Max Is Making WaxCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:331946

-

2Lover ManCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:211946

-

3The GipsyCharlie Parker - Howard McGhee Quintet00:03:031946

-

4Be BopCharlie Parker00:02:551946

-

5Home Cooking I (S' Wonderful)Charlie Parker00:02:221947

-

6Home Cooking II (Cherokee)Charlie Parker00:02:081947

-

7Home Cooking III (I Got Rhythm)Charlie Parker00:02:271947

-

8Lullaby In RhythmCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

9Yardbird SuiteCharlie Parker00:02:141947

-

10BluesCharlie Parker00:01:061947

-

11This Is Always MasterCharlie Parker Quartet00:03:131947

-

12This Is AlwaysCharlie Parker Quartet00:03:091947

-

13Dark ShadowsCharlie Parker Quartet00:04:071947

-

14Dark Shadows IICharlie Parker Quartet00:03:141947

-

15Dark Shadows III (Master)Charlie Parker Quartet00:03:101947

-

16Dark Shadows IVCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:591947

-

17Bird's NestCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:511947

-

18Bird's Nest IICharlie Parker Quartet00:02:501947

-

19Bird's Nest IIICharlie Parker Quartet00:02:441947

-

20Cool Blues (Hot Blues)Charlie Parker Quartet00:01:591947

-

21Cool Blues Blowtop BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:231947

-

22Cool Blues (Master)Charlie Parker Quartet00:03:081947

-

23Cool BluesCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:481947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Relaxin' At CamarilloCharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

2Relaxin' At Camarillo II (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:03:071947

-

3Relaxin' At Camarillo IIICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:011947

-

4Relaxin' At Camarillo IVCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:571947

-

5CheersCharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:111947

-

6Cheers IICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

7Cheers IICharlie Parker's New Stars00:03:021947

-

8Cheers IV (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:03:031947

-

9Carvin' The BirdCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:441947

-

10Carvin' The Bird (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:02:441947

-

11Stupendous (Master)Charlie Parker's New Stars00:02:531947

-

12StupendousCharlie Parker's New Stars00:02:591947

-

13Dee Dee's DanceCharlie Parker - Howard McGhee Quintet00:03:571947

-

14Donna LeeCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:181947

-

15Donna Lee IICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:341947

-

16Donna Lee IIICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:381947

-

17Donna Lee (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:361947

-

18Chasin' The BirdCharlie Parker All Stars00:02:571947

-

19Chasin' The Bird IICharlie Parker All Stars00:03:231947

-

20Chasin' The Bird (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:471947

-

21CherylCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:011947

-

22BuzzyCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:021947

-

23Buzzy IICharlie Parker All Stars00:00:361947

-

24Buzzy IIICharlie Parker All Stars00:02:411947

-

25Buzzy IVCharlie Parker All Stars00:00:241947

-

26Buzzy (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:311947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1MilestonesCharlie Parker00:00:101947

-

2MilestonesCharlie Parker00:02:381947

-

3MilestonesCharlie Parker00:02:471947

-

4Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:00:481947

-

5Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:03:121947

-

6Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker00:02:531947

-

7Half NelsonCharlie Parker00:02:531947

-

8Half NelsonCharlie Parker00:02:461947

-

9Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:00:571947

-

10Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:02:241947

-

11Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:00:061947

-

12Sippin' At BellsCharlie Parker00:02:311947

-

13KokoCharlie Parker00:01:101947

-

14Hot HouseCharlie Parker00:05:191947

-

15Fine And DandyCharlie ParkerSteven James00:03:311947

-

16KokoCharlie Parker00:01:101947

-

17On The Sunny Side Of The StreetCharlie ParkerDorothy Fields00:03:301947

-

18How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:071947

-

19Tiger Rag (O.D.J.B.)Charlie Parker00:03:551947

-

2052 Street ThemeCharlie Parker00:00:491947

-

21Night In TunisiaCharlie ParkerFranck Paparelli00:05:151947

-

22Dizzy AtmosphereCharlie Parker00:04:081947

-

23Groovin' HighCharlie Parker00:05:191947

-

24ConfirmationCharlie Parker00:05:431947

-

25KokoCharlie Parker00:04:211947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1DexterityCharlie Parker00:02:591947

-

2DexterityCharlie Parker00:02:591947

-

3Bongo BopCharlie Parker00:02:451947

-

4Bongo BopCharlie Parker00:02:441947

-

5Prezology (Dewey Square)Charlie Parker00:03:291947

-

6Dewey SquareCharlie Parker00:03:031947

-

7Dewey SquareCharlie Parker00:03:091947

-

8The HymnCharlie Parker00:02:321947

-

9The Hymn (Superman)Charlie Parker00:02:281947

-

10Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:081947

-

11Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:101947

-

12Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker00:03:111947

-

13Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:03:451947

-

14Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:03:241947

-

15Bird Feathers (Schnourphology)Charlie Parker00:02:521947

-

16Klact-Oveeseds-TeneCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

17Klact-Oveeseds-TeneCharlie Parker00:03:061947

-

18Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:02:431947

-

19Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:03:021947

-

20My Old FlameCharlie Parker00:03:121947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:04:071947

-

2Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:03:521947

-

3Out Of NowhereCharlie ParkerEdward Heyman00:03:061947

-

4Don't Blame MeCharlie ParkerDorothy Fields00:02:501947

-

552 Street ThemeCharlie Parker00:01:421947

-

6Donna LeeCharlie Parker00:02:581947

-

7Fats FlatCharlie Parker00:02:501947

-

8Groovin' HighCharlie Parker00:03:321947

-

9Koko (C.P.) AnthropologyCharlie Parker00:06:181947

-

10Drifting On A Reed (Giant Swing)Charlie Parker00:03:011947

-

11Drifting On A ReedCharlie Parker00:02:571947

-

12Drifting On A Reed (Air Conditioning)Charlie Parker00:02:551947

-

13QuasimadoCharlie Parker00:02:581947

-

14Quasimado (Trade Winds)Charlie Parker00:02:591947

-

15Charlies WigCharlie Parker00:02:521947

-

16Charlies Wig (Bongo Bop)Charlie Parker00:02:511947

-

17Charlies WigCharlie Parker00:02:471947

-

18Bongo Beep (Dexterity)Charlie Parker00:03:031947

-

19Bongo Beep (Bird Feathers)Charlie Parker00:03:021947

-

20CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:01:021947

-

21CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:00:361947

-

22CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:03:021947

-

23CrazeologyCharlie Parker00:03:031947

-

24How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:261947

-

25How Deep Is The OceanCharlie Parker00:03:071947

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The BirdCharlie Parker00:04:481947

-

2RepetitionCharlie Parker with The Neal Hefti Orchestra00:03:021947

-

3Another Hair Do (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:151947

-

4Another Hair Do (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:441947

-

5Another Hair Do (Take 3)Charlie Parker All Stars00:01:051947

-

6Another Hair Do (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:411947

-

7Bluebird (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:561947

-

8Bluebird (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:541947

-

9Klaunstance (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:481947

-

10Bird Gets The Worm (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:03:031947

-

11Bird Gets The Worm (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:111947

-

12Bird Gets The Worm (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:381947

-

13Announcer 1Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:211948

-

1452nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:181948

-

15KokoCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:281948

-

16Barbados (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:411948

-

17Barbados (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:471948

-

18Barbados (Take 3)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:391948

-

19Barbados (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:321948

-

20Ah Leu Cha (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:391948

-

21Ah Leu Cha (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:591948

-

22Constellation (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:201948

-

23Constellation (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:321948

-

24Constellation (Take 3)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:061948

-

25Constellation (Take 4)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:221948

-

26Constellation (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:301948

-

27Parker's Mood (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:03:241948

-

28Parker's Mood (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:261948

-

29Parker's Mood (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:03:031948

-

30Drifting On A ReedCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:251948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Perharps (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:051948

-

2Perharps (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:281948

-

3Perharps (Take 3)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:111948

-

4Perharps (Take 4)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:201948

-

5Perharps (Take 5)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:411948

-

6Perharps (Take 6)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:201948

-

7Perharps (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:351948

-

8Marmaduke (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:01:161948

-

9Marmaduke (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:531948

-

10Marmaduke (Take 3)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:561948

-

11Marmaduke (Take 4)Charlie Parker All Stars00:01:001948

-

12Marmaduke (Take 5)Charlie Parker All Stars00:03:001948

-

13Marmaduke (Take 6)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:351948

-

14Marmaduke (Take 7)Charlie Parker All Stars00:00:491948

-

15Marmaduke (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:481948

-

16SteeplechaseCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:061948

-

17Merry Go Round (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:221948

-

18Merry Go Round (Master)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:291948

-

19Announcer 2Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:031948

-

20Groovin' HighCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:221948

-

21Big FootCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:091948

-

22OrnithologyCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:551948

-

23On A Slow Boat To ChinaCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:531948

-

24Announcer 3Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:00:321948

-

25Hot HouseCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:331948

-

26Salt PeanutsCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:131948

-

27Announcer 4Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:231948

-

28Chasin' The BirdCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:121948

-

29Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:341948

-

30How High The Moon (Take 1)Charlie Parker All Stars00:02:551948

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1No Noise (Part 1 and 2)Charlie Parker with Machito and His Aro-cuban Orchestra00:05:561948

-

2Mango MangueCharlie Parker with Machito and His Aro-cuban Orchestra00:02:571948

-

3Annonceur 5Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:161949

-

4Half NelsonCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:181949

-

5White ChristmasCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:241949

-

6Little Willie LeapsCharlie Parker All Stars00:03:421949

-

7Announcer 6Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:161949

-

8Be BopCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:111949

-

9On A Slow Boat To ChinaCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:591949

-

10OrnithologyCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:491949

-

11Groovin HighCharlie Parker All Stars00:06:031949

-

12East Of The SunCharlie Parker All Stars00:05:011949

-

13CherylCharlie Parker All Stars00:04:181949

-

14Announcer 7Charlie Parker All StarsInconnu00:01:051949

-

15How High The Moon (Take 2)Charlie Parker All Stars00:04:481949

-

16Overtime (Take 1)Metronome All Stars00:03:121949

-

17Overtime (Take 2)Metronome All Stars00:04:411949

-

18Victory Ball (Take 1)Metronome All Stars00:02:451949

-

19Victory Ball (Take 2)Metronome All Stars00:02:431949

-

20Victory Ball (Take 3)Metronome All Stars00:04:191949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcer ICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:591949

-

2Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:111949

-

3Announcer IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:261949

-

4Be-BopCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:191949

-

5Announcer IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:151949

-

6Hot HouseCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:141949

-

7Announcer IVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:141949

-

8Oop Bop Sh BamCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:561949

-

9Announcer VCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:401949

-

10Scrapple From The Apple IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:331949

-

11Announcer VICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:221949

-

12Salt PeanutsCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:071949

-

13Announcer VIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:381949

-

14Announcer VIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:571949

-

15Groovin HighCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:441949

-

16Announcer IXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

17Announcer XCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:001949

-

18Scrapple From The Apple IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:251949

-

19Announcer XICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

20BarbadosCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:511949

-

21Announcer XIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:081949

-

22Salt Peanuts IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:341949

-

23Announcer XIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:301949

-

24OkiedokeCharlie Parker with Machito And His Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:101949

-

25Leap HereJazz At The Philarmonic00:11:271949

-

26IndianaJazz At The Philarmonic00:11:211949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Lover Come Back To MeJazz At The Philarmonic00:15:371949

-

2Announcer XIVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:071949

-

3Scrapple From The Apple IVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:331949

-

4Announcer XVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:161949

-

5Barbados IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:531949

-

6Announcer XVICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:131949

-

7Be-Bop IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:191949

-

8Announcer XVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:051949

-

9Groovin' High IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:451949

-

10Announcer XVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:051949

-

11ConfirmationCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:321949

-

12Announcer XIXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:121949

-

13Salt Peanuts IIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:451949

-

14Announcer XXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:091949

-

15Half NelsonCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:321949

-

16Announcer XXICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:151949

-

17A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:381949

-

18Announcer XXIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:241949

-

19Scrapple From The Apple VCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:401949

-

20Announcer XXIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:231949

-

21DeedleCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:081949

-

22Announcer XXIVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:301949

-

23What ThisCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:361949

-

24Announcer XXVCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:251949

-

25CherylCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:511949

-

26Announcer XXVICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:271949

-

27AnthropologyCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:091949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcer XXVIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:101949

-

2Hurry HomeCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:241949

-

3Deedle IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:021949

-

4Royal Roost BopCharlie Parker All-Stars00:02:121949

-

5Announcer XXVIIICharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:071949

-

6Cheryl IICharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:211949

-

7Announcer XXIXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:00:211949

-

8On A Slow Boat To ChinaCharlie Parker All-Stars00:03:381949

-

9Announcer XXXCharlie Parker All-Stars00:01:141949

-

10Chasin The BirdCharlie Parker All-Stars00:06:331949

-

11CardboardCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:111949

-

12VisaCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:021949

-

13SegmentCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:221949

-

14Diverse SegmentCharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:191949

-

15Passport ICharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:02:571949

-

16Passport IICharlie Parker and His Orchestra00:03:031949

-

17Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:341949

-

18Hot House IICharlie Parker Quintet00:05:451949

-

19Allen S AlleyCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:291949

-

2052nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:561949

-

21Salt Peanuts IVCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:441949

-

22Blues FinalCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:001949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The OpenerCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:12:491949

-

2Lester LeapsCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:12:321949

-

3Embraceable YouCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:10:441949

-

4Just FriendsCharlie Parker & Jazz At The Philharmonic00:11:001949

-

5The CloserCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:331949

-

6Everything Happens To MeCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:181949

-

7April In ParisCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:091949

-

8SummertimeCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:481949

-

9I Didn't Know What Time It WasCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:151949

-

10If I Should Lose YouCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:521949

-

11Annonce/OrnithologyCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:351949

-

12CherrylCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:001949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1KokoCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:031949

-

2Bird Of ParadiseCharlie Parker Quintet00:06:081949

-

3Now's The TimeCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:141949

-

452nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:01:351950

-

5WahooCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:351950

-

6Round MidnightCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:141950

-

7This Time The Dreams On MeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:231950

-

8Dizzy AtmosphereCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:07:051950

-

9A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:381950

-

10Move/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:511950

-

11The Street BeatCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:09:211950

-

12Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:131950

-

13Little Wille Leaps/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:05:541950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1OrnithologyCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:07:571950

-

2I'll Remember April/52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:09:391950

-

3Embraceable YouCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell TrioGeorge & Ira Gerschwin00:06:071950

-

4Cool BluesCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:06:531950

-

552nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker, Fats Navarro & The Bud Powell Trio00:02:121950

-

6I Don T Know What Time It WasCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:381950

-

7OrnithologyCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:301950

-

8I Cover The WaterfrontCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:201950

-

9VisaCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:001950

-

10Embraceable YouCharlie Parker Quintet00:01:471950

-

11Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:401950

-

12Star EyesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:541950

-

1352nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:141950

-

14ConfirmationCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:161950

-

15Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:201950

-

16Hot HouseCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:481950

-

17What's NewCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:461950

-

18Now's The TimeCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:181950

-

19Smoke Gets In Your EyesCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:341950

-

2052nd Street Theme IICharlie Parker Quintet00:01:131950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Star EyesCharlie Parker QuartetG. Depaul00:03:291950

-

2BluesCharlie Parker Quartet00:02:471950

-

3I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker QuartetJ. McHugh00:02:511950

-

4Lament For CongaCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:05:441950

-

5Mambo FortunatoCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:05:131950

-

6BloomdidoCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:261950

-

7An Oscar From TreadwellCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:211950

-

8An Oscar From Treadwell MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:231950

-

9MohawkCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:491950

-

10Mohawk MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:361950

-

11My Melancholy BabyCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:241950

-

12Leap FrogCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:301950

-

13Leap Frog MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:341950

-

14Leap FrogCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:001950

-

15Relaxin' With MeCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:03:571950

-

16Relaxin' With Me MasterCharlie Parker with Machito and his Afro-Cuban Orchestra00:02:471950

-

17I Can't Get StartedCharlie Parker QuartetI. Gershwin00:04:531950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

152 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:231950

-

2AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:221950

-

3Just FriendsCharlie Parker QuintetS.M. Lewis00:03:051950

-

4AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:131950

-

5April In ParisCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:161950

-

6A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:231950

-

752 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:191950

-

8AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:191950

-

9Just Friends IICharlie Parker QuintetS.M. Lewis00:03:031950

-

10AnnonceCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:131950

-

11April In Paris IICharlie Parker Quintet00:03:021950

-

12Medley I Bewitched SummertimeCharlie Parker QuintetL. Hart00:05:071950

-

13Medley II I Cover The Waterfront Gone With The WindCharlie Parker QuintetE. Heyman00:04:351950

-

14Easy To Love 52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:011950

-

15Medley III What's New It's The Talk Of The TownCharlie Parker QuintetJ. Burke00:06:451950

-

16Moose The Mooche 52nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:10:351950

-

17Lover Come Back To MeCharlie Parker with The Tony Scott QuartetO. Hammerstein II00:17:121950

-

1852 nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker with The Tony Scott Quartet00:01:391950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Dancing In The DarkCharlie Parker with StringsH. Dietz00:03:111950

-

2Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker with StringsE. Heyman00:03:071950

-

3LauraCharlie Parker with StringsJ. Mercer00:02:581950

-

4East Of The SunCharlie Parker with StringsB. Bowman00:03:391950

-

5They Can't Take That Away From MeCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:201950

-

6Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with StringsCole Porter00:03:301950

-

7I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker with StringsDorothy Fields00:03:341950

-

8I'm In The Mood For LoveCharlie Parker with StringsDorothy Fields00:03:301950

-

9I'll Remember AprilCharlie Parker with StringsP. Johnstone00:03:071950

-

10Annonce répétitionCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:051950

-

11What Is This Thing Called Love DesannonceCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:021950

-

12Annonce Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with StringsInconnu00:03:081950

-

13RépétitionCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:411950

-

14April In ParisCharlie Parker with StringsE.Y. Harburg00:03:111950

-

15Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:141950

-

16What Is This Thing Called Love DesannonceCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:511950

-

17What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:081950

-

18What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:521950

-

19April In ParisCharlie Parker with StringsE.Y. Harburg00:03:101950

-

20RepetitionCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:461950

-

21Easy To LoveCharlie Parker with Strings00:02:231950

-

22RockerCharlie Parker with Strings00:03:001950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1CelebrityCharlie Parker00:01:391950

-

2BalladCharlie Parker00:03:031950

-

3There's A Small HotelCharlie Parker00:10:191950

-

4These Foolish ThingsCharlie Parker00:02:081950

-

5Keen And PeachyCharlie Parker00:06:321950

-

6Hot HouseCharlie Parker00:09:091950

-

7AnthropologyCharlie Parker00:05:581950

-

8CheersCharlie Parker00:06:391950

-

9Lover ManCharlie Parker00:01:531950

-

10Cool BluesCharlie Parker00:04:261950

-

11AnthropologyCharlie Parker00:05:561950

-

12Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:06:331950

-

13Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:02:401950

-

14Cool BluesCharlie Parker00:05:161950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Star EyesCharlie Parker00:02:121950

-

2All The Things You AreCharlie Parker00:05:031950

-

3Strike Up The BandCharlie Parker00:04:421950

-

4How High The MoonCharlie Parker00:03:411950

-

5Body And SoulCharlie ParkerE. Heymann00:09:231950

-

6Fine And DandyCharlie Parker00:05:451950

-

7Lady BirdCharlie Parker00:02:481950

-

8Jumpin With Symphony SidCharlie Parker00:00:521950

-

9AnthropologyCharlie Parker00:04:121950

-

10Embraceable YouCharlie Parker00:05:051950

-

11CherylCharlie Parker00:04:241950

-

12Salt Peanuts / Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker00:05:161950

-

13Introduction - CancionCharlie Parker00:02:571950

-

14MamboCharlie Parker00:03:111950

-

15TransitionCharlie Parker00:02:471950

-

16Introduction to 6/8 – 6/8Charlie Parker00:02:111950

-

17Transition & JazzCharlie Parker00:03:441950

-

18Rhumba Abierto - CodaCharlie Parker00:02:371950

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Au PrivaveCharlie Parker00:02:471951

-

2Au PrivaveCharlie Parker00:02:431951

-

3She RoteCharlie Parker00:03:171951

-

4She RoteCharlie Parker00:03:141951

-

5K.C. BluesCharlie Parker00:03:291951

-

6Star EyesCharlie Parker00:03:381951

-

7My Little Suede ShoesCharlie Parker00:03:091951

-

8Un Poquito De Tu AmorCharlie Parker00:02:461951

-

9Tico TicoCharlie Parker00:02:501951

-

10FiestaCharlie Parker00:02:541951

-

11Why Do I Love You ?Charlie Parker00:03:031951

-

12Why Do I Love You ?Charlie Parker00:03:031951

-

13Why Do I Love You ?Charlie Parker00:03:051951

-

14RockerCharlie Parker00:02:341951

-

15Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker00:02:131951

-

16Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker00:00:571951

-

17Just FriendsCharlie Parker00:03:321951

-

18Everything Happens To MeCharlie Parker00:02:381951

-

19East Of The SunCharlie Parker00:03:211951

-

20LauraCharlie Parker00:02:591951

-

21Dancing In The DarkCharlie Parker00:03:411951

-

22Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker00:00:401951

-

23What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker00:02:011951

-

24LauraCharlie Parker00:03:301951

-

25RepetitionCharlie Parker00:02:421951

-

26They Can't Take That Away From MeCharlie Parker00:03:061951

-

27Easy To LoveCharlie Parker00:02:171951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Blue‘ N BoogieCharlie Parker All-StarsDizzy Gillespie00:07:311951

-

2AnthropologyCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:461951

-

3‘Round MidnightCharlie Parker All-StarsB. Hanighan00:03:311951

-

4Night In Tunisia/Jumpin' With Symphony SidCharlie Parker All-Stars00:05:201951

-

5Hot HouseCharlie Parker All-Stars00:04:251951

-

6Embraceable YouCharlie Parker All-StarsG. et I.Gershwin00:03:441951

-

7How High The Moon - OrnithologyCharlie Parker All-StarsNancy Hamilton00:05:231951

-

8Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker00:15:181951

-

9Lullaby In RhythmCharlie Parker00:12:301951

-

10Happy Bird BluesCharlie Parker00:02:521951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1You Go To My HeadCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraHaven Gillespie00:03:101951

-

2Leo The Lion ICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:081951

-

3Cuban HolidayCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:081951

-

4The Nearness Of YouCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraN. Washington00:03:371951

-

5Lemon DropCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:461951

-

6The Goof And ICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:351951

-

7LauraCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestraJohnny Mercer00:02:581951

-

8Four BrothersCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:531951

-

9Leo The Lion IICharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:141951

-

10More MoonCharlie Parker with Woody Herman and his orchestra00:03:211951

-

11Blues For AliceCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:521951

-

12Si SiCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:441951

-

13Swedish SchnappsCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:201951

-

14Swedish SchnappsCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:171951

-

15Back Home BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:411951

-

16Back Home BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:531951

-

17Lover ManCharlie Parker QuintetR. Ramirez00:03:311951

-

18All Of MeCharlie Parker/Lennie TristanoGerald Marks00:03:381951

-

19I Can'T Believe That You Re In LoveCharlie Parker/Lennie TristanoJ. McHugh00:04:231951

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1TemptationCharlie Parker Big BandA. Freed00:03:341952

-

2LoverCharlie Parker Big BandR. Rodgers00:03:091952

-

3Autumn In New YorkCharlie Parker Big Band00:03:311952

-

4Stella By StarlightCharlie Parker Big BandN. Washington00:03:001952

-

5Mama InezCharlie Parker QuintetE. Grenet00:02:561952

-

6La CucarachaCharlie Parker QuintetTraditionnel00:02:461952

-

7EstrellitaCharlie Parker QuintetA. Venosa00:02:461952

-

8Begin The BeguineCharlie Parker Quintet00:03:171952

-

9La PalomaCharlie Parker QuintetTraditionnel00:02:441952

-

10Night And DayCharlie Parker Big Band00:02:521952

-

11Almost Like Being In LoveCharlie Parker Big BandA.J. Lerner00:02:371952

-

12I Can'T Get StartedCharlie Parker Big BandIra Gershwin00:03:101952

-

13What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie Parker Big BandCole Porter00:02:401952

-

14Hot HouseCharlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie00:04:451952

-

15Cool BluesJerry Jerome All Stars00:04:231952

-

16OrnithologyJerry Jerome All StarsBenny Harris00:08:211952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Jam BluesCharlie Parker-Norman Granz Jam Session00:14:441952

-

2What Is This Called LoveCharlie Parker-Norman Granz Jam Session00:15:541952

-

3Dearly BelovedCharlie Parker-Norman Granz Jam Session00:01:481952

-

4Funky BluesCharlie Parker-Norman Granz Jam Session00:13:311952

-

5The SquirrelCharlie Parker-Harry Barasin All Stars00:15:431952

-

6Indiana Donna LeeCharlie Parker-Harry Barasin All Stars00:11:511952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Irresistible YouCharlie Parker-Harry Barasin All StarsDe Raye00:06:411952

-

2LizaCharlie Parker-Harry Barasin All StarsG. & I. Gershwin00:10:371952

-

3OrnithologyCharlie Parker QuartetB. Harris00:05:551952

-

452nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quartet00:05:041952

-

5RockerCharlie Parker Quintet with strings00:05:291952

-

6Sly MongooseCharlie Parker Quintet with strings00:03:441952

-

7Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker Quintet with strings00:04:061952

-

8Star EyesCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsD. Raye00:02:301952

-

9This Time The Dream's On MeCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsH. Arlen00:06:211952

-

10Cool BluesCharlie Parker Quintet with strings00:03:031952

-

11My Little Suedes ShoesCharlie Parker Quintet with strings00:04:331952

-

12Lester Leaps in'Charlie Parker Quintet with strings00:04:141952

-

13LauraCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsJ. Mercer00:03:221952

-

14How High The MoonCharlie Parker QuintetN. Hamilton00:05:581952

-

15Embraceable YouCharlie Parker QuintetG. & I. Gershwin00:03:151952

-

1652nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Quintet00:00:231952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Just FriendsCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsJ. Klenner00:03:331952

-

2Easy To LoveCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsCole Porter00:02:261952

-

3RepetitionCharlie Parker Quintet with stringsN. Hefti00:06:061952

-

4A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker Sextet00:07:361952

-

552nnd Street ThemeCharlie Parker Sextet00:02:161952

-

6IntroductionCharlie Parker QuintetInconnu00:00:571952

-

7OrnithologyCharlie Parker Quintet00:04:191952

-

8Cool BluesCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:241952

-

9Groovin' HighCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:291952

-

10Don't Blame MeCharlie Parker QuintetD. Fields00:09:051952

-

11Scrapple From The AppleCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:591952

-

12CherylCharlie Parker Quintet00:05:221952

-

13Jumping With Symphony SidCharlie Parker Quintet00:02:251952

-

14I'll Remember AprilCharlie Parker Sextet00:10:311952

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1The Song Is YouCharlie Parker QuartetO. Hammerstein II00:03:011952

-

2Laird BairdCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:02:481952

-

3KimCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:011952

-

4Kim (Master)Charlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:011952

-

5Cosmic Rays (Master)Charlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:071952

-

6Cosmic RaysCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:03:201952

-

7CompulsionCharlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:05:461953

-

8Serpent's Tooth 1Charlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:07:021953

-

9Serpent's Tooth 2Charlie Parker SextetMiles Davis00:06:191953

-

10‘Round MidnightCharlie Parker SextetTheolonius Monk00:07:081953

-

11Intro / Cool BluesCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsCharlie Parker00:02:261953

-

12Bernie's TuneCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Miller00:03:191953

-

13Don't Blame MeCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsD. Fields00:03:291953

-

14Wahoo / ClosingCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Harris00:03:571953

-

15OrnithologyCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsB. Harris00:04:401953

-

16Embraceable YouCharlie Parker and Jazz Workshop All StarsG et I. Gershwin00:03:461953

-

17Your Father's MoustacheCharlie Parker with The Bill Harris/Chubby Jackson HerdB. Harris00:05:111953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Fine And DandyCharlie Parker with The OrchestraK. Swift00:03:281953

-

2These Foolish ThingsCharlie Parker with The OrchestraJ. Strachey00:03:241953

-

3Light GreenCharlie Parker with The OrchestraBill Potts00:03:371953

-

4Thou SwellCharlie Parker with The Orchestral. Hart00:03:521953

-

5WillisCharlie Parker with The OrchestraBill Potts00:05:251953

-

6Don't Blame MeCharlie Parker with The OrchestraD. Fields00:03:161953

-

7Something To Remember You By / Taking A Chance On Love / Blue RoomCharlie Parker with The OrchestraA. Schwartz00:03:151953

-

8RoundhouseCharlie Parker with The OrchestraGerry Mulligan00:03:141953

-

9Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:05:091953

-

10I'll Walk AloneCharlie Parker QuartetS. Cahn00:04:511953

-

11OrnithologyCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:04:221953

-

12Out Of NowhereCharlie Parker QuartetJ. Green00:04:321953

-

13Groovin' HighCharlie ParkerDizzy Gillespie00:03:481953

-

14Cool BluesCharlie Parker QuartetCharlie Parker00:04:301953

-

15Star EyesCharlie Parker QuartetD. Raye00:05:281953

-

16Moose The Mooche / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker QuartetB.Y. Foster00:05:551953

-

17Broadway / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker QuartetT. McRae00:03:241953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1PerdidoCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearJuan Tizol00:08:161953

-

2Salt PeanutsCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearDizzy Gillespie00:07:361953

-

3All The Things You Are / 52Nd Street ThemeCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearJerome Kern00:07:561953

-

4WeeCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearD. Best00:06:461953

-

5Hot HouseCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearT. Dameron00:09:091953

-

6A Night In TunisiaCharlie Parker with The Quintet of The YearF. Paparelli00:07:391953

-

7The Bluest BluesCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioCharlie Parker00:06:411953

-

8On The Sunny Side Of The StreetCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioJ. McHugh00:02:561953

-

9Moose The MoocheCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioCharlie Parker00:05:151953

-

10Cheryl / Lullaby Of BirdlandCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioGeorge Shearing00:08:041953

-

11Dance Of The InfidelsCharlie Parker with Bud Powell TrioBud Powell00:05:281953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1In The Still Of The NightCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:271953

-

2Old FolksCharlie ParkerW. Robinson00:03:371953

-

3If I Love AgainCharlie ParkerB. Oakland00:02:301953

-

4Announcement 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:391953

-

5Cool Blues 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:361953

-

6Announcement 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:101953

-

7Scrapple From The Apple 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:021953

-

8Announcement 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:571953

-

9LauraCharlie ParkerD.Raskin00:06:331953

-

10Closing AnnouncementCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:341953

-

11Ornithology 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:011953

-

12Out Of Nowhere 1Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:05:451953

-

13My Funny Valentine 1Charlie ParkerR. Rogers00:06:371953

-

14Cool Blues 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:531953

-

15Chi-Chi 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:081953

-

16Chi-Chi 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:451953

-

17Chi-Chi 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:051953

-

18I Remember YouCharlie ParkerV. Schertzinger00:03:051953

-

19Now's The Time 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:031953

-

20ConfirmationCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:571953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Now's The Time 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:181953

-

2Don't Blame MeCharlie ParkerJ. McHugh00:05:001953

-

3Dancing In The CeilingCharlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:02:301953

-

4Cool Blues 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:501953

-

5Groovin' High 1Charlie ParkerDizzy Gillespie00:05:091953

-

6Ornithology 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:02:541953

-

7BarbadosCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:031953

-

8Cool Blues 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:421953

-

9Announcement 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:141953

-

10Ornithology 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:511953

-

11Introduction 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:281953

-

12My Little Suede Shoes 1Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:161953

-

13Introduction 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:291953

-

14Now's The Time 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:051953

-

15Groovin' High 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:101953

-

16Announcement 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:211953

-

17CherylCharlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:471953

-

18Introduction 3Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:041953

-

19Ornithology 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:291953

-

2052nd Street ThemeCharlie ParkerThelonius Monk00:01:321953

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Announcement 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:211954

-

2Ornithology 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:471954

-

3Announcement 7Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:191954

-

4Out Of Nowhere 2Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:09:321954

-

5Announcement 8Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:321954

-

6Cool Blues 5Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:521954

-

7Announcement 9Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:451954

-

8Scrapple From The Apple 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:04:371954

-

9Now's The Time 4Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:09:101954

-

10Announcement 10Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:00:491954

-

11Out Of Nowhere 3Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:05:431954

-

12My Little Suede Shoes 2Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:05:051954

-

13Jumpin With Symphony Sid 1Charlie ParkerLester Young00:01:111954

-

14Cool Blues 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:06:221954

-

15Announcement 11Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:01:021954

-

16Ornithology 6Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:07:351954

-

17Announcement 12Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:01:221954

-

18Out Of Nowhere 4Charlie ParkerJ. Green00:04:221954

-

19Jumpin' With Symphony Sid 2Charlie ParkerLester Young00:02:341954

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Night And DayCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:031954

-

2My Funny Valentine 2Charlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:03:201954

-

3CherokeeCharlie ParkerR. Noble00:02:591954

-

4I Get A Kick Out Of You 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:04:531954

-

5I Get A Kick Out Of You 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:351954

-

6Just One Of Those ThingsCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:431954

-

7My Heart Belongs To DaddyCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:211954

-

8I've Got You Under My SkinCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:03:351954

-

9What Is This Thing Called LoveCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:161954

-

10RepetitionCharlie ParkerNeal Hefti00:02:441954

-

11Easy To LoveCharlie ParkerCole Porter00:02:131954

-

12East Of The SunCharlie ParkerB. Bowman00:03:431954

-

13The Song Is YouCharlie ParkerJ. Kern00:04:411954

-

14My Funny Valentine 3Charlie ParkerR. Rodgers00:02:021954

-

15Cool Blues 7Charlie ParkerCharlie Parker00:03:011954

-

16Love For Sale 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:311954

-

17Love For Sale 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:331954

-

18I Love Paris 1Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:071954

-

19I Love Paris 2Charlie ParkerCole Porter00:05:071954

by

Phone

at 01.43.74.90.24

by

to Frémeaux & Associés, 20rue Robert Giraudineau, 94300 Vincennes, France

in

Bookstore or press house

(Frémeaux & Associés distribution)

at my

record store or Fnac

(distribution : Socadisc)

I am a professional

Bookstore, record store, cultural space, stationery-press, museum shop, media library...