- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Books (in French)

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Our Catalog

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- Africa

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - Movie Soundtracks

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Youth

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

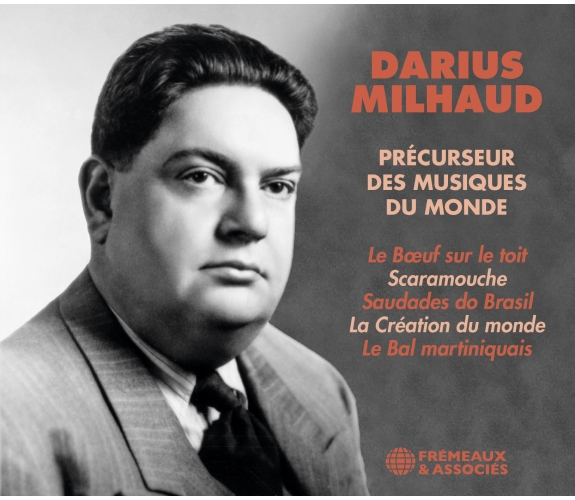

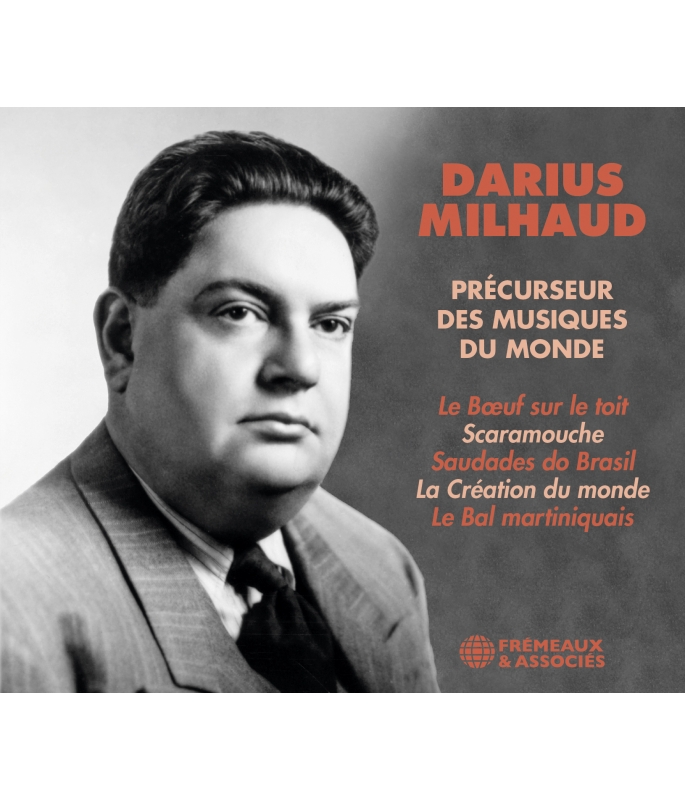

Le Bœuf Sur le toit • Scaramouche • Saudades do Brasil • La Création du monde • Le Bal martiniquais

Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, Fats Waller

Ref.: FA5891

EAN : 3561302589121

Artistic Direction : Philippe Lesage & Téca Calazans

Label : FREMEAUX & ASSOCIES

Total duration of the pack : 2 hours 24 minutes

Nbre. CD : 2

Le Bœuf Sur le toit • Scaramouche • Saudades do Brasil • La Création du monde • Le Bal martiniquais

In February 1917, Darius Milhaud went to Rio de Janeiro. He was 25, and he disembarked when the Carnival was in full swing. He stayed until the end of 1919, then travelled to Martinique and the USA. During his three stays he discovered remarkable sounds that would make him a precursor, in the first two decades of the 20th century, of the intricate relationship between world music and the scholarly classical music of Europe.

Philippe LESAGE

CD1 : LE BOEUF SUR LE TOIT : MINNEAPOLIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, DIR MITROPOULOS • ATÉ EU : OITO BATUTAS • ATÉ A VOLTA : OITO BATUTAS • APANHEI-TE CAVAQUINHO : ERNESTO NAZARETH • SCARAMOUCHE : MARCELLE MEYER & DARIUS MILHAUD • BREJEIRO : BANDA DO CORPO DOS BOMBEIROS DE RIO DE JANEIRO • GRAÚNA : OITO BATUTAS • ESCOVADO : ERNESTO NAZARETH • SAUDADES DO BRASIL : DARIUS MILHAUD • SAUDADES DO BRASIL : JACQUES FÉVRIER • SAUDADES DO BRASIL : LE TRIGENTUOR LYONNAIS • DANSES DE JACAREMIRIM : LOUIS KAUFMAN & ARTUR BALSAM.

CD2 : LA CRÉATION DU MONDE : ORCHESTRE DU THÉÂTRE DES CHAMPS-ELYSÉES, DIR DARIUS MILHAUD • CARNAVAL À LA NOUVELLE-ORLÉANS : ARTHUR GOLD & ROBERT FIZDALE • SOUNDS OF AFRICA : EUBIE BLAKE • I WOULD LIKE TO KNOW WHY : WIENER & DOUCET • KING PORTER STOMP : JELLY ROLL MORTON • 3 RAG-CAPRICES : VIENNA SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, DIR HENRI SWOBODA • SOUVENIR DU BOEUF SUR LE TOIT : WIENER & DOUCET • HANDFUL OF KEYS : FATS WALLER • LE BAL MARTINIQUAIS : ROBERT & GABY CASADESUS • EN L’AI MONE LA : STELLIO • CINÉMA FANTAISIE : RENÉ BENEDETTI ET JEAN WIENER.

DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE : PHILIPPE LESAGE ET TECA CALAZANS

BADEN POWELL • PAULO MOURA • WALDIR AZEVEDO • ABEL...

JULIAN BREAM • LAURINDO ALMEIDA • VICTORIA DE LOS...

Noel Rosa - Dorival Caymmi - Vinicius De Moraes

Rio de Janeiro - New York - Los Angeles

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1Le Boeuf sur le toit, opus 58Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, dir. MitropoulosDarius Milhaud00:14:081945

-

2Até EuOito BatutasDarius Milhaud00:03:141923

-

3Até a VoltaOito BatutasDarius Milhaud00:03:121923

-

4Apanhei-te CavaquinhoErnesto NazarethDarius Milhaud00:02:141930

-

5Scaramouche - Mouvement I : VifDarius Milhaud, Marcelle MeyerDarius Milhaud00:02:451930

-

6Scaramouche - Mouvement II : ModéréDarius Milhaud, Marcelle MeyerDarius Milhaud00:03:371930

-

7Scaramouche - Mouvement III : BrazileiraDarius Milhaud, Marcelle MeyerDarius Milhaud00:02:081930

-

8BrejeiroBanda do Corpo dos Bombeiros de Rio de JaneiroDarius Milhaud00:03:321904

-

9GraúnaOito BatutasDarius Milhaud00:03:221923

-

10EscovadoErnesto NazarethDarius Milhaud00:02:321907

-

11Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - SorocabaDarius MilhaudDarius Milhaud00:01:261930

-

12Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - SumareDarius MilhaudDarius Milhaud00:01:501930

-

13Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - CorcovadoDarius MilhaudDarius Milhaud00:01:451928

-

14Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - IpamenaDarius MilhaudDarius Milhaud00:01:531928

-

15Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - BotafogoJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:01:531957

-

16Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - LemeJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:02:191957

-

17Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - CopacabanaJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:03:011957

-

18Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - GaveaJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:01:291957

-

19Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - TijucaJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:02:061957

-

20Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - PainerasJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:01:171957

-

21Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - LaranjeirasJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:01:071957

-

22Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 - PaysanduJacques FévrierDarius Milhaud00:02:021957

-

23Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 b - OuvertureLe trigentuor LyonnaisDarius Milhaud00:00:421957

-

24Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 b - SorocabaLe trigentuor LyonnaisDarius Milhaud00:01:391957

-

25Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 b - Leme 2Le trigentuor LyonnaisDarius Milhaud00:02:001957

-

26Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 b - Gavea 2Le trigentuor LyonnaisDarius Milhaud00:01:251957

-

27Danses de Jacaremirim, opus 256 - SambinhaLouis Kaufman, Artur BalsamDarius Milhaud00:01:151949

-

28Danses de Jacaremirim, opus 256- TanguinhoLouis Kaufman, Artur BalsamDarius Milhaud00:02:191949

-

29Danses de Jacaremirim, opus 256 - ChorinhoLouis Kaufman, Artur BalsamDarius Milhaud00:01:081949

-

PisteTitleMain artistAutorDurationRegistered in

-

1La Création du monde, opus 81Orchestre du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, dir. Darius MilhaudDarius Milhaud00:14:471932

-

2Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, opus 275 - Mardi Gras ! Chic à La PailleArthur Gold, Robert FizdaleDarius Milhaud00:01:111950

-

3Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, opus 275 - Domino Noir De CajonArthur Gold, Robert FizdaleDarius Milhaud00:02:581950

-

4Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, opus 275 - On Danse Chez Monsieur DegasArthur Gold, Robert FizdaleDarius Milhaud00:01:451950

-

5Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, opus 275 - Mille Cents CoupsArthur Gold, Robert FizdaleDarius Milhaud00:02:221950

-

6Sounds of Africa (African Rag)Eubie BlakeEubie Blake00:03:101921

-

7I Would Like to Know WhyJean Wiener, Clément DoucetEubie Blake00:03:041925

-

8King Porter StompJelly Roll MortonJelly Roll Morton00:02:561926

-

93 Rag-Caprices - Sec et muscléVienna Symphony Orchestra, dir. Henri SwobodaDarius Milhaud00:02:201959

-

103 Rag-Caprices - Romance. TendrementVienna Symphony Orchestra, dir. Henri SwobodaDarius Milhaud00:02:151959

-

113 Rag-Caprices - Précis et nerveuxVienna Symphony Orchestra, dir. Henri SwobodaDarius Milhaud00:02:211959

-

12Souvenir du Boeuf sur le toit (medley)Jean Wiener, Clément DoucetDarius Milhaud00:06:401935

-

13Handful of KeysFats WallerThomas Waller00:02:561929

-

14Chanson Créole – Le Bal martiniquais, opus 249Robert Casadesus, Gaby CasadesusDarius Milhaud00:02:371948

-

15Biguine – Le Bal martiniquais, opus 249Robert Casadesus, Gaby CasadesusDarius Milhaud00:04:291948

-

16En L’ai Mone LaStellioStellio00:03:051933

-

17Cinéma fantaisie, opus 58 bRené Benedetti, Jean WienerDarius Milhaud00:12:391928

DARIUS

MILHAUD

PRÉCURSEUR

DES MUSIQUES

DU MONDE

Le Bœuf sur le toit

Scaramouche

Saudades do Brasil

La Création du monde

Le Bal martiniquais

A PRECURSOR OF WORLD MUSIC

In February 1917, Darius Milhaud went to Rio de Janeiro. He was 25, and he disembarked when the Carnival was in full swing. He stayed until the end of 1919, then travelled to Martinique and the USA. During his three stays he discovered remarkable sounds that would make him a precursor, in the first two decades of the 20th century, of the intricate relationship between world music and the scholarly classical music of Europe. Philippe LESAGE

CD1 : 1) Le Bœuf sur le toit : Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, dir Mitropoulos • 2) Até Eu : Oito Batutas • 3) Até a Volta : Oito Batutas • 4) Apanhei-te Cavaquinho : Ernesto Nazareth • 5 à 7) Scaramouche : Marcelle Meyer & Darius Milhaud • 8) Brejeiro : Banda do Corpo dos Bombeiros de Rio de Janeiro • 9) Graúna : Oito Batutas • 10) Escovado : Ernesto Nazareth • 11 à 14) Saudades do Brasil : Darius Milhaud • 15 à 22) Saudades do Brasil : Jacques Février • 23 à 26) Saudades do Brasil : Le trigentuor Lyonnais • 27 à 29) Danses de Jacaremirim : Louis Kaufman & Artur Balsam.

CD2 : 1) La Création du monde : Orchestre du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, dir Darius Milhaud • 2 à 5) Carnaval à la Nouvelle-Orléans : Arthur Gold & Robert Fizdale • 6) Sounds of Africa : Eubie Blake • 7) I Would Like to Know Why : Wiener & Doucet • 8) King Porter Stomp : Jelly Roll Morton • 9 à 11) 3 Rag-Caprices : Vienna Symphony Orchestra, dir Henri Swoboda • 12) Souvenir du Bœuf sur le toit : Wiener & Doucet • 13) Handful of Keys : Fats Waller • 14 à 15) Le Bal martiniquais : Robert & Gaby Casadesus • 16) En L’ai Mone La : Stellio • 17) Cinéma fantaisie : René Benedetti et Jean Wiener.

DARIUS MILHAUD,

A PRECURSOR OF WORLD MUSIC

An overture to world music?

From February 1917 to the middle of 1919, Darius Milhaud visited Brazil, Martinique and the USA, and his stay in the region marked an intellectual and aesthetic connection with the popular music of the Americas. If this anthology focuses on works of music linked to the latter — all the more so since these are the pieces that capture the most attention today — it is because this composer’s work upholds the notion that in the first decades of the 20th century, Milhaud was already a precursor of the intricate relationship between world music and the more scholarly compositions written in Europe.

A precursor of interrelations between scholarly and popular music?

When Milhaud arrived in Rio in February 1917 he was 25 years old and already a budding composer. But the great characteristics of his style had surfaced earlier, in music he’d written for the theatre (André Gide signed the libretto), or in the music to which he set poems by Francis Jammes and Paul Claudel. Already interested in polytonality, he was considered (somewhat unsuitably) as an avant-gardist composer, although he belonged to the luminous French tradition of a Bizet or a Chabrier. In Brazil he encountered the same solar intensity he’d known in his native Provence, while discovering a tonic form of Brazilian popular music that didn’t fail to astonish and seduce him; his own musical artistry would become a translation of it. Hence the question: from the beginning of the twenties, shouldn’t we consider him a precursor of the intricacies between “learned” European works and what we now call “world music”? Everyone will form their own opinion after listening to the pieces selected for this anthology, all of them explicit references to the musical genres of Brazil, Martinique, and jazz.

Darius Milhaud’s first version of his memoirs (published as “Notes without Music”) would later carry the title “My Happy Life.” It’s true that his intellectual curiosity, his appetite for life despite an always fragile health, and his own personality, allowed him to connect with all the new ideas that were setting fire to a roaring twentieth century (and he did so with communicative pleasure). He couldn’t avoid immersing himself in the Art Nègre movement, Cubism, the Ballets Russes, or France’s Années folles (Americans called it “The Jazz Age”). Milhaud (b.1892, d.1974) had a gift for launching projects with different personalities, like Paul Claudel, Jean Cocteau, Fernand Léger, Raoul Dufy, Arthur Honegger... or the pianists Jean Wiener, Clément Doucet and Robert Casadesus, or again the violinist René Benedetti. Then there was his friendship with Blaise Cendrars, which makes you wonder if he hadn’t somehow been the “musical shadow” of Cendrars, with whom he conceived the ballet La Création du monde. Milhaud and Cendrars were artists who knew how to capture modernity, firstly in the early days of film and then in the vitality — sometimes frivolous, but always providing rich lessons — that was to be found in popular music. Both were adventurers, nomads without blinkers, and so always on the look-out for things that titillated the mind and senses. Both loved the films of Chaplin, and both dived into Brazilian culture with delight.

Milhaud journeyed to Brazil, the French Antilles and the USA before the arrival of the twenties. The variety of popular music he discovered enchanted him so much that he picked up his pen at once. How could he appropriate this foreign music, if not by drawing its juices and its very marrow into his own composing? Not that he followed the ethnological path of a Bela Bartok, who recorded traditional music in the field, no: Milhaud preferred an immersion in everyday life, and let his own sensibilities capture whatever sounded strange to the ear of a European. He was no plagiarist — despite the hostile observations of some of his critics — but rather a kind of cannibal who swallowed foreigners and then spit them out in another form... He was close to the aesthetic of the modernist Brazilian poets, Oswald de Andrade and Mario de Andrade, the author of the famous novel Macunaïma. In our opinion it was that sleight of hand, that plasticity in his composing, that predisposed him to become a precursor of world music in our old Europe.

To make Milhaud’s approach easier to understand, this anthology has a choice of sound-illustrations taken from the popular music of Brazil and America in that period, and they enable comparison with his own works. In pieces like Le Bœuf sur le toit, Scaramouche, the Bal martiniquais or Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, one can see the clear influence on Milhaud of the music he heard on his voyage.

Darius Milhaud and Brazil.

His health was precarious as we’ve said (he suffered from rheumatism throughout his life) and so Milhaud was exempted from military service and never went to war. In 1917 he joined Paul Claudel at the French Embassy in Rio de Janeiro, the country’s capital at the time, and remained in Brazil until November 1918. So he was in Rio for the 1917 Carnival, when the samba Pelo Telefone was on everyone’s lips. It fascinated him. We might point out that this was not yet the time when samba schools paraded through the streets (they would only become familiar in the thirties) but there were already ranchos and corsos along the Avenida Atlantica.

In 1920, Milhaud wrote an article in the Revue Musicale under the title “Brazil” in which he said, “It would be useful for Brazil’s serious composers to understand the importance of the musicians writing tangos, maxixes, sambas and cateretês, like Tupinambá or Nazareth, a genius. The richness of the rhythm, the continually renewed fantasy, the verve, vivacity and prodigious imagination we encounter in these two masters are the glory of Brazilian art.” Further on he added, “The rhythms of this popular music intrigued and fascinated me. There were imperceptible suspensions in syncopation, breaths with no concern, slight pauses that I found difficult to overcome. I purchased many maxixes and tangos, and finally I was able to express and analyse these little nothings that are so Brazilian. One of the finest composers in this musical genre is Nazareth, whose habit it was to play piano outside the entrance to the cinema on the Avenida Rio Branco.” (This was the Odeon cinema, which lent its name to a composition that would become part of Brazil’s national heritage). Milhaud concluded, “(Nazareth’s) fluid, impalpable and nostalgic playing also helped me to better know the Brazilian soul.”

Several works written by Milhaud contain references to popular Brazilian music, principally the ones that received a warm welcome in France: Le Bœuf sur le toit, Saudades do Brasil and Scaramouche, to which we must add the Danses de Jacaremirim, which are certainly less often performed but just as beautiful. We can look at them here in more detail.

Le Bœuf sur le toit

This emblematic title (also the name of a Parisian restaurant — it means ‘the Ox on the Roof’ — situated at 28, rue Boissy d’Anglas, where high society went slumming every night) is a Frenchified popular song from Brazil named O Boi No Telhado, a “tango brasileiro” written by José Monteiro (nicknamed Zé Boiadero) which was first released at the 1918 carnival. Monteiro visited Paris as a singer and percussionist, performing with Oito Batutas, and in the folklore of the Nordeste, the “partilha do boi” sings of sharing cuts of beef. The restaurant was owned by Louis Moysès, and it was the venue where Jean Wiener and Clément Doucet appeared with verve and elegance.

Le Bœuf sur le toit would become a ballet based on a canvas by Cocteau with decors by Raoul Dufy, and it is a suite of episodes structured around Brazilian melodies with unexpected harmonic twists. It has three cycles of cumulative songs (each with an additional verse) plus a coda; each cycle includes four iterations of the rondo’s theme and a passage of twelve major tones and several minor tones.

In articles for As crônicas Bovinas (or “Bœuf Chronicles”) in the webpages devoted to the Bœuf sur le toit, the musicologist, writer and critic Daniella Thompson points to borrowings from Darius Milhaud (we might have said rather “allusions” or “quotations») while emphasising that he never revealed the origin of his sources except to write that “I had the leisure to study the folklore of this country, to attune myself to the rhythms of the tangos, maxixes and sambas, to the melancholy of the Portuguese fados.” Milhaud added, “My work is enormously influenced by a memory of the Brazil I loved so much. I thought of doing a type of rhapsody based on music I had heard there, but in a rather free form. I wanted to do a piece in one interrupted movement, colourful and torrential. I also thought of Chaplin’s films, hence the subtitle ‘Fantaisie pour le cinéma.’ Originally I thought that it might accompany a film. What Cocteau wanted was a representation of it that he could put on a stage.”

The idea that Cocteau was defending took on physical shape when the poet sold the project to the Comte de Beaumont, the proprietor of the theatre La Comédie des Champs-Elysées. He imagined an American bar during Prohibition, although we might wonder why, since the music contains no reference to North America. The work was staged in London, and also in Brazil where the press, whose nationalist leanings were exacerbated, reacted with animosity on hearing borrowings from local popular music: they deemed that they gave a negative image of their country.

Popular themes quoted by Milhaud

So where did they come from, those “little nothings” of Darius Milhaud, those “typically Brazilian, imperceptible suspensions in the syncopation,” unless they were sourced in works by the two “masters” to whom he refers, namely Marcello Tupynambá and Ernesto Nazareth? There is no denying that eleven of the thirty melodies came from the pens of the latter. Nazareth’s work is quoted in Carioca, Escovado, and Valsa; as for Tupynambá, one can note seven themes, Até Eu and Até a Volta, plus Tristeza do Caboclo, Sodade, Sou Batuta and Viola Cantadira, not forgetting the first melody, Sao Paulo Futuro, which is a maxixe. But other composers were visited, and they were not insignificant either: Caboca de Caxanga was written by the wonderful guitarist João Pernambuco, and a tango by Alexandre Levy from Sao Paulo (whose father was French, and who died in 1892) is another melody that was taken up by Milhaud, as are Gaucho, the famous theme by Chiquinha Gonzaga, and Flor de Abacate by Alvaro Sandim (b.1864, d.1919). The titles Sertanejo and Para Todo were penned by Eduardo Souto, who was the first black artist to enjoy huge success.

Notes on the Brazilian musicians present in this anthology.

These artists were to be found in all classes of society in the Brazil of that period, and Milhaud could not avoid discovering them and enjoying their work. The following provides a few biographical notes on these musicians, all of them still remembered thanks to compositions that marked their era. To begin with, they include Marcelo Tupynambá (Marcello Tupynambá is the old spelling). It was the pseudonym of the artist Fernando Alvares Lobo (b.1881 – d.1953), who was actually a certified engineer from Sao Paulo, although he was known above all as a musician and composer. His father was the leader of a town band, and Marcello was privileged (at age 15) to accompany the renowned mulatto flautist Patapio Silva. In 1914 he composed the music for the revue Sao Paulo Futuro (Viola Cantadera, Matuto and Maricota, Sai da Chuva are themes from the revue). His melodies Até Eu and Até a Volta are performed here by the group Os Oito Batutas, and it is easy to verify the presence of quotations from them used by Darius Milhaud. Another musician absolutely not to be neglected is Anacleto de Medeiros (1866-1907), who was one of the principal figures on the music scene of the period. He was the leader of A Banda do Corpo Dos Bombeiros of Rio De Janeiro (in other words, the band of the Rio Fire Brigade) and a mulatto clarinettist who was an immense composer of choro pieces (he convinced big bands that they should be playing them.) Here his own orchestra plays a theme by Ernesto Nazareth, Brejeiro, which means “a saucy rascal”... If you had to name a “choro genius,” or vital figure of the genre, then it would be Alfredo da Rocha Viana Junior (1898-1973), better known as Pixinguinha. A composer, flautist and saxophonist, Pixinguinha was also a sought-after arranger and he would visit Paris for six months (in 1922) with the Oito Batutas (meaning the choro’s “eight aces”). Among others, the group included his brother China, his great friend Donga, author of the famous samba Pelo Telefone, and João da Baiana, all of them more or less inseparably linked with candomble and macumba. This group varied in size and was active until the early thirties, when it distilled music that was astonishingly modern. Joao Pernambuco (real name Joao Teixeira Guimaraes, 1883-1947), was from Nordeste. He was illiterate, a self-taught guitarist with a complex character who also became a composer (praised to the skies by Villa Lobos, among others.) He founded the group Caxanga, which also included Pixinguinha and Donga. We selected Graúna from his work, played here by Os Oito Batutas, a theme not too distant from Caboca de Caxanga quoted in Le Bœuf sur le Toit. Orphaned at the age of eleven, and marked by his mother’s taste for the music of Chopin, Ernesto Nazareth (1863-1934) was a pianeiro (the Brazilian word for a “popular piano player”) but also a remarkable composer in the world of Brazilian popular music. He is present in our anthology thanks to his solo piano versions of Apanhei-te Cavaquinho and Escovado. His immense hit Brejeiro is played by Rio’s Banda do Corpo Dos Bombeiros in a delicious colonial atmosphere that retains all its savour even today.

Cinéma fantaisie

The Cinéma Fantaisie Op.58B for violin and piano is played here by violinist René Benedetti with Jean Wiener at the piano (the cadenza is by Arthur Honegger). In its initial version the piece was conceived for violin and orchestra (two flutes, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, two horns, two trumpets, trombone, drums and strings.) Composed in 1919, its first performance was given in 1921 and it is in fact separate from the Bœuf sur Le toit, with its title even confirming Milhaud’s taste for films. We confess we love this piece performed by René Benedetti as much as the seminal Le Bœuf sur le toit.

Scaramouche, Op. 156 b

The first performance of this work was given by Marcelle Meyer and Ida Jankelevitch in 1937, and it was composed at the request of Marguerite Long, who wished to have a short piece for her two pupils mentioned above. In our anthology we present the version recorded in 1938 by Milhaud himself in duet with Marcelle Meyer. The composer exploits stage-music that he had just composed to accompany the text of a play dated 1937 (inspired by Molière) and performed by the Scaramouche Theatre under the direction of his friend Charles Vildrac. The first movement has a “Commedia dell’arte” style; the second is an expressive, melancholy theme that is rather “bluesy” (this second movement borrows from Bolivar’s opus 148 dated 1935, conceived for an opera by Jules Supervielle), while the final movement entitled A Brazileira (the correct Portuguese title would be A Brasileira) is a boisterous samba that always impresses listeners.

Saudades do Brasil opus 67

These are twelve dances for piano based on a rhythm in two: tango brasileiro, a variant of the choro (quite different from the Argentinean tango) and a samba. Our anthology presents the transcription for orchestra (there are flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, trumpets and trombones, all in pairs, plus timbales, drums and strings.) This musical and intellectual description of the districts of Rio de Janeiro is as beautiful, seductive and innovative as the pieces that Isaac Albeñiz dedicated to Andalusia, which speaks for itself. Ipanema is dedicated to Arthur Rubinstein, Gavea to Madam Henrique Oswald, Tijuca to the Catalan pianist Ricardo Viñes, and Paisandu to Paul Claudel. We propose four melodies from the Saudades do Brasil performed by Milhaud himself and the other melodies by Jacques Février, in other words, approaches that complement each other.

La Création du monde op 81 a

Milhaud’s affinities with the new musical forms of the Americas found their first expression with La Création du monde. It’s true that after leaving Rio de Janeiro in November 1918, Milhaud spent four months travelling around the French Antilles and visiting New York. Like Debussy and Ravel, he became acquainted with nascent jazz forms and ragtime, and the Création du monde is one of the most personal jazz adaptations to be found in European music of the period.

The Création du monde is a ballet imagined by Cendrars, who took a liking to the “Art Nègre” movement in vogue in Paris during the Roaring Twenties. The ballet’s plot is taken from the Anthologie Nègre that Cendrars had just published. The action begins at the moment of chaos with three deities in consultation. Vegetal and animal life are gradually born, and then Man and Woman execute a dance of desire that concludes with a kiss that heralds the arrival of spring.

This is a piece conceived for a small orchestra of 17 instruments, with a solo part for an alto saxophone (a rare occurrence at the time.) The work has six parts played in a single movement. The wind instruments are privileged, while the piano and strings are used principally as rhythm instruments. This is actually a marriage between classical music and jazz, a story of musical hybridation that evokes ragtime, the blues and the first recordings of Paul Whiteman. Jazz harmonies coexist with the polytonal writing that is characteristic of the composer, while the curved architecture with its central fugue evoke European models. Note the glissandi from the trombones, the muted trumpets, and the melodic line that falls to the saxophone alone. The initially negative criticism of this work diminished with time.

Cendrars drew his friend Fernand Léger into the adventure. For the decors, Léger drew inspiration from Primitivism and African masks, and Rolf de Maré’s Ballets Suédois, with choreographer Jean Börlin, would give a performance on 25 October 1923 conducted by Vladimir Golschmann.

Milhaud and the USA

The other works referring to the USA and black music would be Carnaval à la Nouvelle-Orléans, a piece for two pianos dated 1947, and Trois Rag-Caprices. The latter are less open to being criticised for plagiarism; in fact they even constitute a perfect illustration of the way in which Milhaud appropriated popular ingredients. They enhance his palette of colours and rhythms while retaining the spirit of his compositions carrying the scents of Brazil. In addition to his first voyage, Milhaud would reside in the USA as a teacher between 1940 and 1947, when he fled from antisemitism and the reality that the Nazis had catalogued him a “degenerate composer.” We thought it a good idea to allow listeners to compare his compositions with the innovative recordings of such jazz musicians as Eubie Blake, Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller. Pianist Eubie Blake (1887-1983), whose first recording was made in 1917, enjoyed a long association with singer/bandleader Noble Sissle (1889-1975) and he composed Shuffle Along, one of the first black musicals to be a hit show on Broadway. The medley entitled Souvenir du Bœuf sur le Toit presented by Jean Wiener and Clément Doucet is present here to illustrate the atmosphere that was to be found in the restaurant in the rue Boissy d’Anglas, an ambiance where jazz and Broadway musicals were dominant. The megalomaniac Jelly Roll Morton (1885-1941), a highly colourful character of mixed-race who hailed from New Orleans, was very proud of his French ancestry and provided a synthesis of ragtime with a “Latin tint” that was very representative of the city’s mixed cultures. As for Fats Waller (b.1904, d.1943), he revealed a gift of the gab and generous swing that easily explains his success with the public.

Le Bal martiniquais op 249

When he travelled back to France, Darius Milhaud paused his journey in Martinique, which he had already visited in November 1918. He composed La Liberté des Antilles, a song cycle for voice and piano, based on Creole texts (Bonjour Messieurs les libérateurs, Trois ans de souffrance). A few years beforehand in 1941, lulled by his souvenirs, he had written Le Bal martiniquais (of which an orchestral version also exists). As with the pieces linked to Brazil and the USA, Milhaud adopted the same creative process with its mixed-culture approach: the learned classical music of Europe in a remodelled hybrid with allusions, quotes from the music of the New World, all of that with a generous smile.

Teca CALAZANS and Philippe LESAGE

Adapted into english by Martin Davies

This anthology is dedicated to the composer Georges Delerue (1925-1992) who was Darius Milhaud’s pupil.

© 2025 FRÉMEAUX & ASSOCIÉS

Discographie

DARIUS MILHAUD, PRÉCURSEUR DES MUSIQUES DU MONDE

CD1

1) Le Bœuf sur le toit, opus 58

Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, dir Dimitri Mitropoulos

33 t Columbia US ML 2032

Enregistré à Minneapolis le 2 mars 1945

2) Até Eu (Marcelo Tupinambà)

Oito Batutas

Victor 73 – 826 B / 1923

3) Até a Volta (Marcelo Tupinambà)

Oito Batutas

Victor 73 – 825 B / 1923

4) Apanhei-te Cavaquinho (Ernesto Nazareth)

Ernesto Nazareth (piano)

Odeon 10718 – 10 septembre 1930

5) Mouvement I : Vif

6) Mouvement II : Modéré

7) Mouvement III : Brazileira

Scaramouche, opus 165 b

Marcelle Meyer & Darius Milhaud sur pianos Pleyel

78 t Gramophone DB 5086

Enregistré à Paris le 6 décembre 1938

8) Brejeiro (Ernesto Nazareth)

Banda do Corpo dos Bombeiros de Rio de Janeiro

Odeon 40621 / 1904

9) Graúna (João Pernambuco)

Oito Batutas

Victor 78-828 A / 1923

10) Escovado (Ernesto Nazareth)

Ernesto Nazareth (piano)

Odeon 20436 / 1907

11) Sorocaba

12) Sumare

13) Corcovado

14) Ipanema

Saudades do Brasil, opus 67

Darius Milhaud, piano

78 t Columbia LFX 40

Enregistré le 8 novembre 1928 (13 et 14) et le 13 janvier 1930 (11 et 12)

15) Botafogo

16) Leme

17) Copacabana

18) Gavea

19) Tijuca

20) Paineras

21) Laranjeiras

22) Paysandu

Saudades do Brasil, opus 67

Jacques Février – piano

33 t Ducretet Thomson 300 C 048

Enregistré à Paris le 17 &18 septembre 1957

23) Ouverture

24) Sorocaba

25) Leme

26) Gavea

Saudades do Brasil, opus 67 b

Orchestré par Darius Milhaud

Le Trigentuor Lyonnais dir Charles Strony

78 t Gramophone K 5720

Enregistré mai 1929

27) Sambinha

28) Tanguinho

29) Chorinho

Danses de Jacaremirim, opus 256

Louis Kaufman (violon) & Artur Balsam (piano)

78 T Capitol P- 8071

Enregistré à Paris en octobre 1949

CD2

1) La Création du monde, opus 81

Orchestre de 19 solistes dirigés par Darius Milhaud

78 t Columbia LFX 251- 252

Enregistré à Paris en février 1932

2) Mardi Gras ! Chic à La Paille

3) Domino Noir De Cajon

4) On Danse Chez Monsieur Degas

5) Mille Cents Coups

Carnaval à la Nouvelle Orléans, opus 275

Arthur Gold & Robert Fizdale (pianos)

33 t Columbia Masterworks ML 2128

Enregistré le 13 janvier 1950

6) Sounds of Africa (African Rag) (Eubie Blake)

Eubie Blake (piano)

Enregistré à New York en juillet 1921

7) I Would Like to Know Why (Eubie Blake et Noble Sissle)

Jean Wiener & Clément Doucet (pianos)

78 t Columbia D 13011

Enregistré à Londres le 14 décembre 1925

8) King Porter Stomp (F.J.R. Morton)

Jelly Roll Morton (piano)

78T Vocalion C 166 / E2869

Enregistré à Chicago le 20 avril 1926

9) Sec et musclé

10) Romance. Tendrement

11) Précis et Nerveux

3 Rag-Caprices, opus 78

Vienna Symphony Orchestra, dir Henry Swoboda

33 t Westminster WL 5951

Enregistré en octobre 1959

12) Souvenir du Bœuf sur le toit (medley)

Jean Wiener & Clément Doucet (pianos)

78t Pathé PA 627

Enregistré à Paris le 10 mai 1935

13) Handful of Keys (Thomas Waller)

Thomas « Fats » Waller (piano)

78 t Victor 27768

Enregistré à New York en mars 1929

14) Chanson Créole – Le Bal martiniquais, opus 249

15) Biguine – Le Bal martiniquais, opus 249

Robert & Gaby Casadesus (pianos)

78 t Columbia US 71831

Enregistré à New York le 18 décembre 1948

16) En L’ai Mone La (Stellio)

Orchestre de l’Elan. Stellio (cl), Henri Boye (bjo), Finote Attuly (p), Paul Mathias(chacha, chant), Hnany (batterie)

78t Cristal CP 1044

Enregistré à Paris en novembre 1933

17) Cinéma fantaisie, opus 58 b

Cadence Arthur Honegger ; René Benedetti (violon), Jean Wiener (piano)

78 t Columbia D 15074 – 15075

Enregistré à Paris le 13 juin 1928